CoDesignS Education for Sustainable Development: A Framework for Embedding Education for Sustainable Development in Curriculum Design

Abstract

:1. Introduction

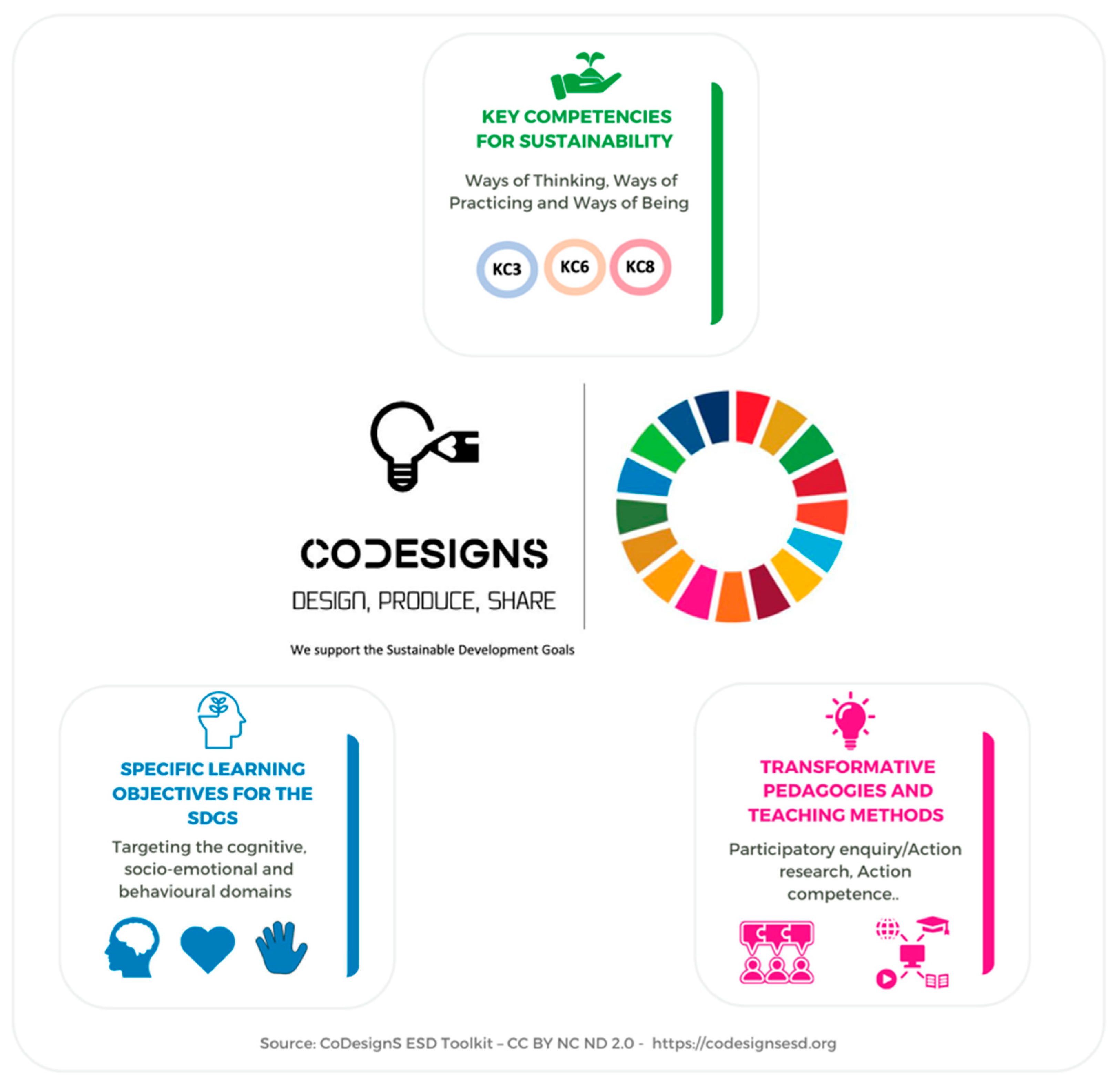

2. The Framework

2.1. Key Competencies for Sustainability

2.2. Specific Learning Objectives for the SDGs

2.3. Transformative Pedagogies and Teaching Methods

2.4. CoDesignS ESD Toolkit

3. Methods and Approach

4. Results

4.1. Pillar 1: Key Competencies for Sustainability

4.1.1. Systems Thinking

4.1.2. Future Thinking

4.1.3. Normative Competency

4.1.4. Strategic Competency

4.1.5. Critical Competency

4.1.6. Collaboration Competency

4.1.7. Self-Awareness

4.1.8. Integrative Problem-Solving Competency

4.2. Pillar 2: Learning Objectives for the SDGs

4.2.1. Cognitive Domain (the Head)

4.2.2. Socio-Emotional Domain (the Heart)

4.2.3. Behavioral Domain (the Hands)

4.3. Pillar 3: Transformative Pedagogies

4.3.1. Action Research

4.3.2. Problem-Based Learning

4.3.3. Role Plays and Simulations

4.3.4. Group Work

4.3.5. Fieldwork

4.3.6. Personal Development Planning (PDP)

4.3.7. Flipped Lectures

4.3.8. Assessments

4.4. Usefulness of the Toolkit

4.4.1. Practical Application

4.4.2. Design and Ease of Use

4.4.3. Case Studies

4.4.4. Visual Information

4.4.5. Link to Professional Framework

4.5. Feedback for Further Toolkit Development

4.5.1. Use of Language

4.5.2. Examples and Case Studies

4.5.3. Being Culturally, Locally Relevant

4.5.4. Workshops

4.5.5. Assessments

4.5.6. Visuals

4.5.7. Linking to Framework

4.5.8. Mapping Key Competencies

4.5.9. Application to Existing Curricula

5. Discussion

Potential Model Adjustments

- Clarification and Integration of Competencies:

- ○

- Clearly differentiate ESD-specific competencies from general educational competencies.

- ○

- Develop guidelines for institutions to integrate ESD competencies with existing ones to avoid redundancy and reduce the perception of an ‘extra hurdle’.

- ○

- Provide case studies or examples showing how ESD competencies can complement and enhance existing competencies within various disciplines.

- Streamlining Administrative Processes:

- ○

- Offer strategies for incorporating ESD learning objectives without an extensive administrative overhaul.

- ○

- Create adaptable templates for learning objectives that can be easily customized to fit into existing curricula and paperwork structures.

- Balanced Focus Across Domains:

- ○

- Ensure a balanced emphasis on the cognitive (the head), socio-emotional (the heart), and behavioral (the hands) domains within the toolkit.

- ○

- Develop resources and activities that encourage the application of theoretical knowledge to real-world sustainability challenges, bridging the knowledge–action gap.

- Practical Application and Transformative Pedagogies:

- ○

- Increase the focus on hands-on, practical approaches to sustainability education, moving beyond theory-heavy content.

- ○

- Encourage the use of transformative pedagogies that foster behavioral change and empower students to act on sustainability knowledge.

- ○

- Provide a repository of pedagogical methods and activities that promote active learning and student engagement in sustainability issues.

- Holistic Integration of Sustainability Concepts:

- ○

- Advocate for the integration of sustainability concepts throughout the course rather than in isolated modules to reinforce their importance and impact.

- ○

- Offer guidance on how to weave sustainability into the fabric of all course contents, making it a consistent theme rather than an add-on.

- Cultural and Background Diversity:

- ○

- Acknowledge and address the diverse backgrounds of students in the design and delivery of ESD.

- ○

- Create resources that are adaptable to various cultural contexts and learning styles, ensuring inclusivity and relevance.

- Empowerment and Leadership Development:

- ○

- Incorporate elements into the toolkit that focus on developing leadership skills and empowering students to become sustainability champions.

- ○

- Facilitate opportunities for students to lead sustainability initiatives and projects, both within and beyond the academic setting.

- Assessment and Evaluation:

- ○

- Align assessments with ESD competencies and learning objectives to ensure they are effectively measuring the desired outcomes.

- ○

- Develop assessment tools that evaluate not only cognitive understanding but also the application and behavioral changes in students.

6. Limitations and Future Research

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- What competencies are you already embedding in your teaching?

- Do you think the case studies presented in the toolkit would help you design and deliver these competencies for SDGs?

- What else would be helpful to guide you in the design and implementation of these competencies in your teaching?

- What do you think about combining the specific learning objectives in your teaching?

- What domains are you already embedding in your teaching?

- Do you think the case studies presented in the toolkit would help you design and deliver learning objectives for the SDGs?

- What else would be helpful to guide you in the design and implementation of these domains in your teaching?

- How important do you think is the use of transformative pedagogies and teaching methods in the design and delivery of ESD?

- Do you use transformative pedagogies and teaching methods in your teaching?

- Do you think the case studies presented in the toolkit would help you design and deliver transformative pedagogical approaches and teaching methods?

- What else would be helpful to guide you in the design and implementation of this pillar in your teaching?

- Is the toolkit well-designed and easy to apply as an instructional tool?

- Is the concept of the toolkit easy to understand and easy to use?

- What additional information or support would you need to incorporate the toolkit into your teaching?

- What do you like most about the toolkit?

- How does the toolkit change your perception of education and the skills, values, and knowledge required to ensure sustainable development?

- Which competencies do you think students already have regarding ESD (covered in step 2)?

- Do you think this toolkit could help to develop the skills necessary to foster responsible citizens amongst you and your peers?

- Which skills are instrumental in developing an understanding of sustainable development (Step 3: Head, Heart, and Hands)?

- Is a sense of community needed for students to develop an understanding of transformative learning?

- Is the language used in the ESD Toolkit relevant?

- Do you think exposure to the ESD will make students more competent?

- To what extent is ESD locally relevant and culturally appropriate?

References

- UNESCO. Education for Sustainable Development Goals: Learning Objectives. 2017. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000247444 (accessed on 22 January 2022).

- Wilhelm, S.; Förster, R.; Zimmermann, A.B. Implementing Competence Orientation: Towards Constructively Aligned Education for Sustainable Development in University-Level Teaching-And-Learning. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Education for Sustainable Development. 2021. Available online: https://www.unesco.org/en/education/sustainable-development (accessed on 22 January 2022).

- Laurie, R.; Nonoyama-Tarumi, Y.; Mckeown, R.; Hopkins, C. Contributions of Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) to Quality Education: A Synthesis of Research. J. Educ. Sustain. Dev. 2016, 10, 226–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wals, A.E.J. Sustainability in higher education in the context of the UN DESD: A review of learning and institutionalisation processes. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 62, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiek, A.; Withycombe, L.; Redman, C.L. Key competencies in sustainability. A reference framework for academic program development. Sustain. Sci. 2011, 6, 203–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Roadmap for Implementing the Global Action Programme on Education for Sustainable Development; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Issues and Trends in Education for Sustainable Development; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lozano-García, F.J.; Gándara, G.; Perrni, O.; Manzano, M.; Elia Hernández, D.; Huisingh, D. Capacity building: A course on sustainable development to educate the educators. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2008, 9, 257–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, R.; Merrill, M.; Sammalisto, K.; Ceulemans, K.; Lozano, F. Connecting Competences and Pedagogical Approaches for Sustainable Development in Higher Education: A Literature Review and Framework Proposal. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, T.L. Competencies and Pedagogies for Sustainability Education: A Roadmap for Sustainability Studies Program Development in Colleges and Universities. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biasutti, M.; Makrakis, V.; Concina, E.; Frate, S. Educating academic staff to reorient curricula in ESD. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2018, 19, 179–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toro-Troconis, M.; Alexander, J.; Frutos-Perez, M. Assessing Student Engagement in Online Programmes: Using Learning Design and Learning Analytics. Int. J. High. Educ. 2019, 8, 171–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, C. A Structured Approach to Online Learning Design in Dental Education. MedEdPublish 2020, 9, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sipos, Y.; Battisti, B.; Grimm, K. Achieving transformative sustainability learning: Engaging heads, hands and heart. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2008, 9, 68–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotton, D.; Winter, J. It’s not just bits of paper and light bulbs: A review of sustainability pedagogies and their potential for use in higher education. In Sustainability Education: Perspectives and Practice Across Higher Education; Earthscan: London, UK, 2010; pp. 39–54. [Google Scholar]

- Association for Learning Design and Education for Sustainable Development (ALDESD). 2022. Available online: https://aldesd.org/codesigns-esd-framework/ (accessed on 20 March 2022).

- AdvanceHE. The UKPSF and Associate Fellowship. 2022. Available online: https://www.advance-he.ac.uk/fellowship/associate-fellowship (accessed on 20 March 2022).

- Portuguez Castro, M.; Gómez Zermeño, M.G. Challenge Based Learning: Innovative Pedagogy for Sustainability through e-Learning in Higher Education. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portuguez Castro, M.; Gómez Zermeño, M.G. Identifying Entrepreneurial Interest and Skills among University Students. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNECE. 2015. Available online: https://unece.org/fileadmin/DAM/env/esd/ESD_Publications/Competences_Publication.pdf (accessed on 26 May 2021).

- Toro-Troconis, M.; Inzolia, Y.; Ahmad, N. Exploring Attitudes towards Embedding Education for Sustainable Development in Curriculum Design. Int. J. High. Educ. 2023, 12, 42–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilbury, D. Monitoring and evaluation during the UN decade of education for sustainable development. J. Educ. Sustain. Dev. 2007, 1, 239–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, B. Taxonomy of Educational Objectives, The Classification of Educational Goals, Handbook I: Cognitive Domain; Longman Group: Harlow, UK, 1956. [Google Scholar]

- Sterling, S. Sustainable Education. Re-visioning Learning and Change. Schumacher Briefing No. 6. In Green Books; UIT Cambridge Ltd.: Cambridge, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Toro-Troconis, M.; Lewis, C. 5 Steps in the Design of Blended Learning Programmes. In Educational Developments; Staff and Educational Development Association (SEDA): London, UK, 2021; Volume 22, Available online: https://www.seda.ac.uk/product/educational-developments-issue-22-4/ (accessed on 25 March 2022).

- Breiting, S.; Mogensen, F. Action Competence and Environmental Education. Camb. J. Educ. 1999, 29, 349–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backman, M.; Pitt, H.; Marsden, T.; Mehmood, A.; Mathijs, E. Experiential approaches to sustainability education: Towards learning landscapes. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2019, 20, 139–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgallis, P.; Bruijn, K. Sustainability teaching using case-based debates. J. Int. Educ. Bus. 2022, 15, 147–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, D.; Stupans, I. Exploring the potential of role play in higher education: Development of a typology and teacher guidelines. Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 2012, 49, 427–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, D.; Alexander, P. Small group teaching: A toolkit for learning. High. Educ. 2013, 36, 4–24. [Google Scholar]

- Ottander, K.; Ekborg, M. Students’ discussions in sustainable development based on their own ecological footprints. In Proceedings of the IOSTE International Symposium on Socio-Cultural and Human Values in Science and Technology Education, Bled, Slovenia, 13–18 June 2010; Available online: http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:mau:diva-11301 (accessed on 16 June 2023).

- Tasler, N.; Dale, V. Learners, teachers and places: A conceptual framework for creative pedagogies. J. Perspect. Appl. Acad. Pract. 2021, 9, 2–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannan, L.; Duhs, R.; Chatterjee, H. Object-based learning: A powerful pedagogy for higher education. In Museums and Higher Education Working Together; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; pp. 159–168. [Google Scholar]

- Robin, B.R. Digital Storytelling: A powerful technology tool for the 21st century classroom. Theory Into Pract. 2008, 47, 220–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andriopoulou, A.; Giakoumi, S.; Kouvarda, T.; Tsabaris, C.; Pavlatou, E.; Scoullos, M. Digital storytelling as an educational tool for scientific, environmental and sustainable development literacy on marine litter in informal education environments (Case study: Hellenic Center for Marine Research). Mediterr. Mar. Sci. 2022, 23, 327–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scannapieco, F.A. Formal debate: An active learning strategy. J. Dent. Educ. 1997, 61, 955–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lister, P.G.; Crisp, B.R. Critical incident analyses: A practice learning tool for students and practitioners. Practice 2007, 19, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schön, D.A. Educating the Reflective Practitioner: Toward a New Design for Teaching and Learning in the Professions; Jossey-Bass: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Sprain, L.; Timpson, W.M. Pedagogy for sustainability science: Case-based approaches for interdisciplinary instruction. Environ. Commun. A J. Nat. Cult. 2012, 6, 532–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayers, J.; Bryant, J.; Missimer, M. The Use of Reflective Pedagogies in Sustainability Leadership Education—A Case Study. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lew, M.D.N.; Schmidt, H.G. Self-reflection and academic performance: Is there a relationship? Adv. Health Sci. Educ. 2011, 16, 529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, I. Critical Thinking, Transformative Learning, Sustainable Education, and Problem-Based Learning in Universities. J. Transform. Educ. 2009, 7, 245–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casinader, N.; Kidman, G. Fieldwork, Sustainability, and Environmental Education: The Centrality of Geographical Inquiry. Aust. J. Environ. Educ. 2018, 34, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toro-Troconis, M. CoDesigns Education for Sustainable Development Framework. 2021. Available online: https://codesignsesd.org (accessed on 20 March 2022).

- Brown, S.; Saxena, D.; Wall, P.J.; Roche, C.; Hussain, F.; Lewis, D. Data Collection in the Global South and Other Resource-Constrained Environments: Practical, Methodological and Ethical Challenges. In Freedom and Social Inclusion in a Connected World, Proceedings of the ICT4D 2022, Lima, Peru, 25–27 May 2022; IFIP Advances in Information and Communication Technology; Zheng, Y., Abbott, P., Robles-Flores, J.A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; Volume 657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romney, A.; Batchelder, W.; Weller, S. Culture as consensus: A theory of culture and informant accuracy. Am. Anthropol. 1986, 88, 313–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, M. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, R.; Cotton, D.; Morrison, D.; Kneale, P. Embedding interdisciplinary learning into the first-year undergraduate curriculum: Drivers and barriers in a cross-institutional enhancement project. Teach. High. Educ. 2022, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holdsworth, S.; Thomas, I. Framework for introducing education for sustainable development into university curriculum. J. Educ. Sustain. Dev. 2015, 9, 137–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cebrián, G. The I3E model for embedding education for sustainability within higher education institutions. Environ. Educ. Res. 2018, 24, 153–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Key Competencies for Sustainability |

|---|

| Systems thinking competency: The abilities to recognize and understand relationships, to analyze complex systems, to think of how systems are embedded within different domains and different scales, and to deal with uncertainty. Anticipatory competency: The abilities to understand and evaluate multiple futures—possible, probable, and desirable; to create one’s own visions for the future; to apply the precautionary principle; to assess the consequences of actions; and to deal with risks and changes. Normative competency: The abilities to understand and reflect on the norms and values that underlie one’s actions and to negotiate sustainability values, principles, goals, and targets in the context of conflicts of interests and trade-offs, uncertain knowledge, and contradictions. Strategic competency: The abilities to collectively develop and implement innovative actions that further sustainability at the local level and further afield. Collaboration competency: The abilities to learn from others; to understand and respect the needs, perspectives, and actions of others (empathy); to understand, relate to, and be sensitive to others (empathic leadership); to deal with conflicts in a group; and to facilitate collaborative and participatory problem solving. Critical thinking competency: The abilities to question norms, practices, and opinions; to reflect on one’s own values, perceptions, and actions; and to take a position in the sustainability discourse. Self-awareness competency: The ability to reflect on one’s own role in the local community and (global) society, to continually evaluate and further motivate one’s actions, and to deal with one’s feelings and desires. Integrated problem-solving competency: The overarching abilities to apply different problem-solving frameworks to complex sustainability problems and develop viable, inclusive, and equitable solution options that promote sustainable development, integrating the above-mentioned competences. |

| Specific Teaching Strategies Advocated to ESD | |

|---|---|

| Role plays and Simulations | Role plays and simulations can be powerful educational experiences in terms of creating scope for empathy with other points of view and vicariously experiencing situations which in real life could be high risk. Role plays support learning in the cognitive, psychomotor, and affective domains [30]. |

| Group discussions | Small group discussions support higher-order learning and critical thinking in allowing different members of the group to share different perspectives, often in the context of solving an authentic problem [31]. Teachers should seek to enable learners with high social anxiety to be part of a group and contribute in ways that are comfortable to them. In the context of sustainability, small group discussions can lead to action competence [32]. |

| Learning landscapes | Learning landscapes can be physical or virtual places where learning can take place in teacher-centered or student-centered ways, depending on the design of the learning experience. However, outdoor learning in particular can motivate students’ curiosity and create a scope for serendipitous discovery [33]. |

| Object-based learning (OBL) | Object-based learning is learning through objects. Traditionally associated with learning through interactions with tangible museum objects, objects can be physical or virtual and stimulate enquiry-based learning [34]. |

| Digital storytelling | Digital storytelling engages the learner through hearing/seeing someone else’s story or telling their own. As with other creative pedagogies, storytelling often includes an emotive element that can be enhanced through multimedia representation and the unique voice and perspective of the storyteller [35]. It has been shown to promote students’ environmental literacy [36]. |

| Debates | Debates stimulate critical thinking in encouraging students to ‘take a side’ in an argument, taking time to construct and defend an argument but also being able to see the validity of alternative perspectives [37]. Asking students to defend a perspective they do not agree with can be a valuable learning experience. |

| Critical incidents | Critical incidents are any events that stimulate learning from reflection, with origins in aviation and anesthesia [38]. They are often used in professional education such as teaching, where a trainee teacher can reflect on an event that typically had an unexpected outcome, triggering what Schön [39] would call reflection in-action, as well as reflection on-action. Critical incidents encourage students to reflect on their learning and develop valuable meta-cognitive skills. |

| Case studies | Case studies stimulate meaningful learning. They are typically professional cases that students might encounter in the workplace, which have been written to encourage students to apply their learning to solving complex, real-world problems through innovative solutions [40]. |

| Reflective accounts | Reflective accounts are typically written in the first person and allow the students to relate their knowledge, skills, and attitudes (collectively, competencies) to their own professional practice. They can be linked to critical incidents or form part of a portfolio the learners develop throughout their studies [41]. Engaging in reflective practice can also improve student assessment performances [42]. |

| Problem-based learning | Problem-based learning differs from problem solving in that it is a specific teaching method that originated in medical education but that has been adopted in other disciplines and been promoted as a transformative pedagogy for sustainable education [43]. Students are typically presented with a case and have to design intended learning outcomes based on the case to drive and direct their learning. In small groups, students are supported by a facilitator at the start of learning about the case and at the end when they present and consolidate their learning. |

| Fieldwork | Fieldwork is typically supervised visits to sites of interest in a specific discipline, where students can be encouraged to develop practical and professional skills. Here, preparation and helping students to translate their in-classroom or in-lab learning into a ‘real-life’ environment is an important scaffolding activity. Fieldwork can be designed around specific SDGs [44]. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ahmad, N.; Toro-Troconis, M.; Ibahrine, M.; Armour, R.; Tait, V.; Reedy, K.; Malevicius, R.; Dale, V.; Tasler, N.; Inzolia, Y. CoDesignS Education for Sustainable Development: A Framework for Embedding Education for Sustainable Development in Curriculum Design. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16460. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152316460

Ahmad N, Toro-Troconis M, Ibahrine M, Armour R, Tait V, Reedy K, Malevicius R, Dale V, Tasler N, Inzolia Y. CoDesignS Education for Sustainable Development: A Framework for Embedding Education for Sustainable Development in Curriculum Design. Sustainability. 2023; 15(23):16460. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152316460

Chicago/Turabian StyleAhmad, Norita, Maria Toro-Troconis, Mohammed Ibahrine, Rose Armour, Victoria Tait, Katharine Reedy, Romas Malevicius, Vicki Dale, Nathalie Tasler, and Yuma Inzolia. 2023. "CoDesignS Education for Sustainable Development: A Framework for Embedding Education for Sustainable Development in Curriculum Design" Sustainability 15, no. 23: 16460. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152316460

APA StyleAhmad, N., Toro-Troconis, M., Ibahrine, M., Armour, R., Tait, V., Reedy, K., Malevicius, R., Dale, V., Tasler, N., & Inzolia, Y. (2023). CoDesignS Education for Sustainable Development: A Framework for Embedding Education for Sustainable Development in Curriculum Design. Sustainability, 15(23), 16460. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152316460