Forest Fires, Stakeholders’ Activities, and Economic Impact on State-Level Sustainable Forest Management

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Area

2.2. Methodology

2.2.1. Forestry Legislation and Fire Protection Regulation

2.2.2. Assessment of Forest-Fire Damages

- Protection of soil, roads, and other structures from erosion, torrents, and flooding (1–5);

- Influence on the water regime and hydropower system (1–4);

- Influence on soil fertility and agricultural production (1–4);

- Influence on climate (1–4);

- Protection and improvement of the human environment (0–3);

- Oxygen generation and atmospheric filtration (1–3);

- Recreation, tourism, and health functions (1–4);

- Influence on fauna and hunting (0–4);

- Protective forests and special purpose forests (8–10).

2.2.3. Fire Weather Index and Assessment of Seasonal Weather Conditions

3. Results

3.1. Legislative and Policy Framework

3.2. Economic Impact of Forest Fires on State Forest Management

3.3. Extreme Weather Conditions and Potential Meteorological Risk of Forest Fires

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- (a)

- According to the definition of fire protection measures and activities, 29 fire-related laws and their bylaws were identified and reviewed. The roles and obligations of different stakeholders were analysed, with an emphasis on Croatian Forests Ltd. and the Croatian Meteorological and Hydrological Service (DHMZ). The laws were grouped according to the main regulation areas: sustainable development, environmental protection, nature protection, biodiversity conservation, protected areas, fire protection, waste management, forestry, agriculture, and other related laws.

- (b)

- The analysis shows the characteristics of different stakeholders and their obligations for the implementation of special fire protection measures, such as the Croatian Fire Association, the Ministry of Defence, the County Fire Associations, regional civil protection offices, public institutions of national parks, public institutions of nature parks, public institutions for the management of protected areas, regional civil protection offices, the Croatian Tourist Board, and the Ministry of Tourism.

- (c)

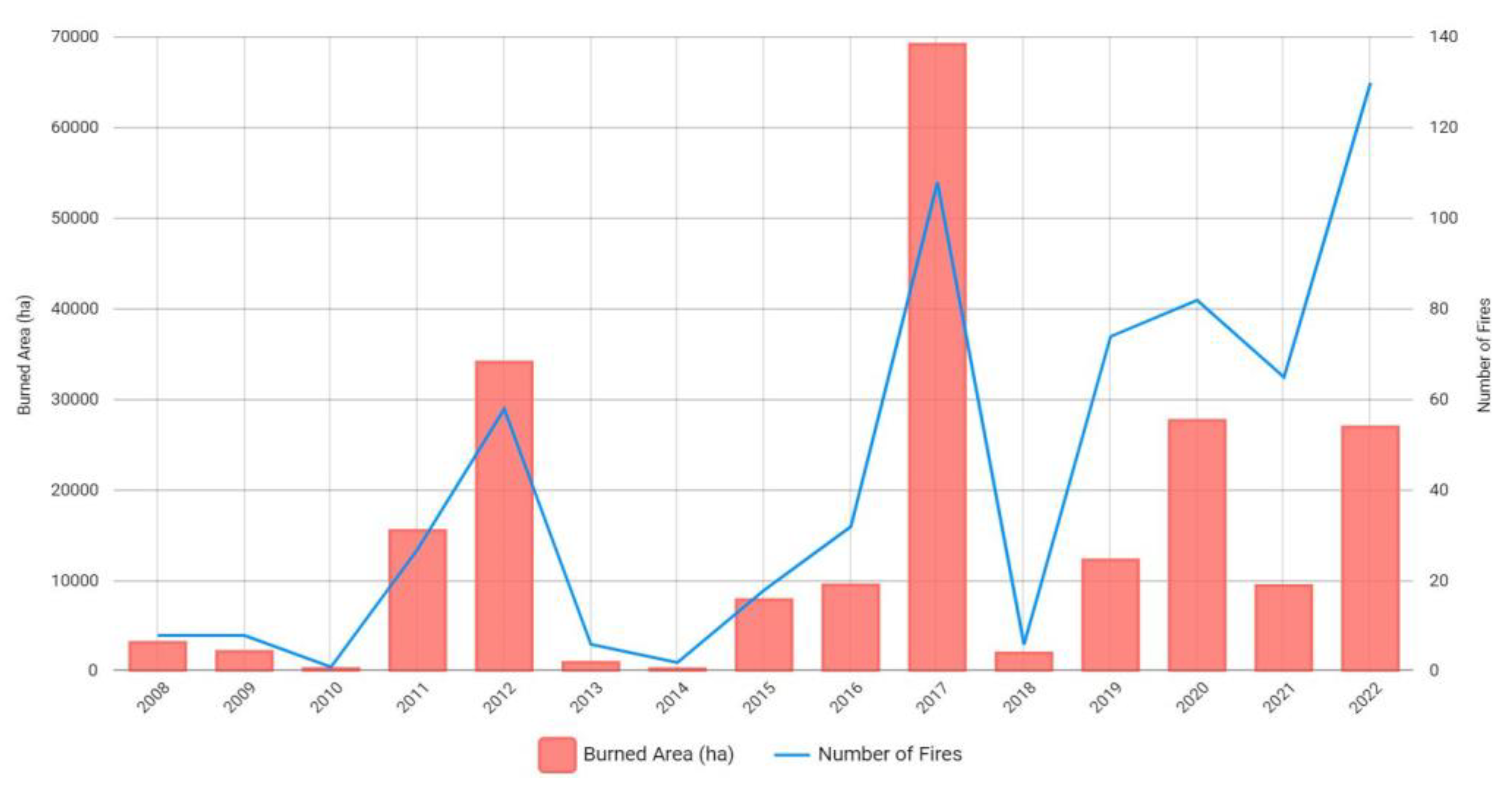

- The economic impact of forest fires on state forest company management was calculated. In the period 2013 to 2022, there were a total of 1271 fires on forest and other land owned by the Republic of Croatia. A total of 100,168 ha was burned. The calculated damage for the first-age class was EUR 8,724,581.9, for growing stock it was EUR 20,979,957.53, and for non-wood forest functions, it was EUR 297,106,185.29 for the state forest company. The company is investing significant resources in the fight against adverse weather conditions, which requires additional operating costs. In the year 2020, the forest-fire damage exceeded EUR 176 million.

- (d)

- Weather conditions were analysed in more detail for fire seasons with the highest and lowest Seasonal Severity Rating (SSR) values in the considered period. In almost all of Croatia, the SSR values for 2017 were above 1.5–2 times the multi-year average for the period 1981–2010. This is because the air temperatures were above average by 3–4 °C, and the precipitation amount was below average (2–31% of the average in the mid-Adriatic) in the summer months. Conversely, the SSR values in 2014 were not higher than 5 and were below average throughout the country due to a very rainy summer. The analyses of correlation among the forest fire damages spent sources for fire protection show that there is no significant benefit if only the state forest company invests in fire protection.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Moreira, F.; Ascoli, D.; Safford, H.; Adams, M.A.; Moreno, J.M.; Pereira, J.M.; Catry, F.X.; Armesto, J.; Bond, W.; González, M.E.; et al. Wildfire management in Mediterranean-type regions: Paradigm change needed. Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 011001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, W.V.; Mooney, H.A.; Cropper, A.; Capistrano, D.; Carpenter, S.R.; Chopra, K.; Dasgupta, P.; Dietz, T.; Duraiappah, A.K.; Kasperson, R.; et al. Millennium Ecosystem Assessment Synthesis Report. 2005. Available online: http://pdf.wri.org/mea_synthesis_030105.pdf (accessed on 14 April 2023).

- Nedeljković, J.; Stanišić, M.; Avdibegović, M.; Curman, M.; Pezdevšek Malovrh, Š. Climate Change Governance in Forestry and Nature Conservation: Institutional Framework in Selected SEE Countries. Šumarski List 2019, 9–10, 445–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. The European Green Deal, Communication from the Commission, COM (2019) 640 Final, Brussels, 11.12.2019. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?qid=1588580774040&uri=CELEX%3A52019DC0640 (accessed on 15 March 2023).

- Griggs, D.; Stafford-Smith, M.; Gaffney, O.; Rockström, J.; Öhman, M.C.; Shyamsundar, P.; Steffen, W.; Glaser, G.; Kanie, N.; Noble, I. Sustainable development goals for people and planet. Nature 2013, 495, 305–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. New EU Forest Strategy for 2030, Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Region, Brussels, 16.7.2021. COM (2021) 572 Final. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52021DC0572 (accessed on 15 March 2023).

- European Commission. EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030. Available online: https://environment.ec.europa.eu/strategy/biodiversity-strategy-2030_en (accessed on 15 March 2023).

- Seidl, R.; Schelhaas, M.J.; Rammer, W.; Verkerk, P.J. Increasing forest disturbances in Europe and their impact on carbon storage. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2014, 4, 806–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganteaume, A.; Barbero, R.; Jappiot, M.; Maillé, E. Understanding future changes to fires in southern Europe and their impacts on the wildland-urban interface. J. Saf. Sci. Resil. 2021, 2, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schelhaas, M.J.; Nabuurs, G.J.; Schuck, A. Natural disturbances in the European forests in the 19th and 20th centuries. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2003, 9, 1620–1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikac, S.; Žmegač, A.; Trlin, D. Utjecaj Klimatskih Promjena i Prirodnih Nepogoda na Šumske Ekosustave, VII; Konferencija Hrvatske Platforme za Smanjenje rizika od Katastrofa/Holcinger, Nataša (ur.); Državna Uprava za Zaštitu i Spašavanje: Zagreb, Croatia, 2018; pp. 162–171.

- European Environment Agency. Nature-Based Solutions in Europe: Policy, Knowledge and Practice for Climate Change Adaptation and Disaster Risk Reduction; EEA Report No 01/2021; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-García, V.; Fulé, P.Z.; Marcos, E.; Calvo, L. The role of fire frequency and severity on the regeneration of Mediterranean serotinous pines under different environmental conditions. For. Ecol. Manag. 2019, 444, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, J.R.; González-Cabán, A.; Rodríguez y Silva, F. Potential Effects of Climate Change on Fire Behavior, Economic Susceptibility and Suppression Costs in Mediterranean Ecosystems: Córdoba Province, Spain. Forests 2019, 10, 679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, S.M.; Alexander, M.E.; DeRose, R.J.; Jenkins, M.J. Fire-Environment Analysis: An Example of Army Garrison Camp Williams, Utah. Fire 2020, 3, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosavec, R.; Barčić, D.; Španjol, Ž.; Oršanić, M.; Dubravac, T.; Antonović, A. Flammability and Combustibility of Two Mediterranean Species in Relation to Forest Fires in Croatia. Forests 2022, 13, 1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Emergency Response Coordination Centre, European Commission, Communication from the Commission Strengthening EU Disaster Management: RescEU Solidarity with Responsibility Solidarity with Responsibility, Brussels, 23.11.2017, COM (2017) 773 Final. Available online: https://civil-protection-humanitarian-aid.ec.europa.eu/what/civil-protection/emergency-response-coordination-centre-ercc_en (accessed on 16 March 2023).

- European Parliament, Council of the European Union. Regulation (EU) No 377/2014 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 3 April 2014 establishing the Copernicus Programme and repealing Regulation (EU) No 911/2010 Text with EEA relevance. Off. J. Eur. Union 2014, 57, 44–66. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Commission Report on Forest Fires: Climate Change Is More Noticeable Every Year. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_21_5627 (accessed on 16 March 2023).

- European Commission. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council and the Committee of the Regions—Strengthening EU Disaster Management: RescEU Solidarity with Responsibility Solidarity with Responsibility; No. COM (2017) 773 Final in Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council and the Committee of the Regions; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- San-Miguel-Ayanz, J.; Costa, H.; de Rigo, D.; Libertà, G.; Artés Vivancos, T.; Durrant, T.; Nuijten, D.; Löffler, P.; Moore, P. Basic Criteria to Assess Wildfire Risk at the Pan-European Level; EUR 29500 EN; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2018; ISBN 978-92-79-98200-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions—Forging a Climate-Resilient Europe—The New EU Strategy on Adaptation to Climate Change, COM (2021) 82 Final. 2021. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=COM%3A2021%3A82%3AFIN (accessed on 18 March 2023).

- Republic of Croatia, Croatian Firefighting Association, 2020, (Hrvatska vatrogasna zajednica), Konačno Izvješće o Realizaciji Programa Aktivnosti u Provedbi Posebnih Mjera Zaštite od Požara od Interesa za Republiku Hrvatsku u 2020. Godini. Available online: https://hvz.gov.hr/vijesti/usvojeno-konacno-izvjesce-o-realizaciji-programa-aktivnosti/2194 (accessed on 18 March 2023).

- Barčić, D.; Dubravac, T.; Vučetić, M. Potential Hazard of Open Space Fire in Black Pine Stands (Pinus nigra J.F. Arnold) in Regard to Fire Severity. SEEFOR-South-East Eur. For. 2020, 2, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čavlina Tomašević, I.; Cheung, K.; Vučetić, V.; Fox-Hughes, P.; Horvath, K.; Telišman Prtenjak, M.; Beggs, P.J.; Malečić, B.; Milić, V. The 2017 Split wildfire in Croatia: Evolution and the role of meteorological conditions. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2022, 22, 3143–3165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). UN Climate Change Annual Report, 2018, p. 62. Available online: https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/UN-Climate-Change-Annual-Report-2018.pdf (accessed on 16 March 2023).

- Giorgi, F.; Lionello, P. Climate change projections for the Mediterranean region. Glob. Planet. Chang. 2008, 63, 90–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pausas, J.G.; Millian, M.M. Greening and browning in a climate change hotspot: The Mediterranean basin. BioScience 2019, 69, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFFIS—Statistics Portal EU JRC. Available online: https://effis.jrc.ec.europa.eu/apps/effis.statistics/ (accessed on 16 March 2023).

- Merlo, M.; Croitoru, L. Valuing Mediterranean Forests: Towards Total Economic Value; Cabi Publishing: Wallingford, UK, 2005; p. 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krznar, A.; Lindić, V.; Vuletić, D. Metodologija Vrednovanja Korisnosti Turističkorekreacijskih Usluga Šuma, Methodology for Evaluating the Usfulness of Tourist-Recreational Benefits of Forest. Radovi 2000, 35, 65–81. [Google Scholar]

- Vuletić, D.; Vrbek, B.; Novotny, V. The Evaluation Results of the Benefits of the Health and Landscape Forests Functions, Rezultati Vrednovanja Koristnosti Zdravstvene i Krajobrazne Funkcije Šume, XXI IUFRO World Congress, Forest and Ocietiy: The Role of Research, 7–12 August 2000; Poster Abstracts: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2000; Volume 3, p. 325. [Google Scholar]

- Posavec, S. Methods of Evaluation Forests—A Renewable Resource in Croatia. In The Multifunctional Role of Forests—Policies, Methods and Case Studies, EFI Proceedings; European Forest Institute: Joensuu, Finland, 2008; pp. 313–318. [Google Scholar]

- Camia, A.; Amatulli, G.; San-Miguel-Ayanz, J. Past and Future Trends of Forest Fire Danger in Europe, JRC Scientific and Technical Reports; European Commision, Joint Research Centre, Institute for Environment and Sustainability: Luxemburg, 2008; p. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Anon. General Forest Management Plan 2016–2025; Ministry of Agriculture, Republic of Croatia: Zagreb, Croatia, 2016.

- Hrvatske Šume, d.o.o. Business Report; Croatian Forests Ltd.: Zagreb, Croatia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Čavlović, J. Prva Nacionalna Inventura Šuma Republike Hrvatske; Ministarstvo Regionalnog Razvoja, Šumarstva i Vodnoga Gospodarstva i Šumarski Fakultet Sveučilišta u Zagrebu: Zagreb, Hrvatska, 2010; p. 300.

- OG 68/18, 115/18, 98/19; Law on Forests. Official Gazette of the Republic of Croatia, Croatian Parliament: Zagreb, Croatia, 2019.

- OG 92/10; Law on Fire Protection. Official Gazette of the Republic of Croatia, Croatian Parliament: Zagreb, Croatia, 2010.

- OG 80/10, 125/19; Law on Fire Fighters. Official Gazette of the Republic of Croatia, Croatian Parliament: Zagreb, Croatia, 2010.

- OG 20/18 115/18, 98/19; Law on Agricultural Land. Official Gazette of the Republic of Croatia, Croatian Parliament: Zagreb, Croatia, 2019.

- Nunez-Mir, G.; Desprez, J.; Iannone, B., III; Clark, T.; Fei, S. An Automated Content Analysis of Forestry Research: Are Socioecological Challenges Being Addressed? J. Forestry 2017, 115, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Art.5, OG 121/97, 131/06, 74/07, 18/08, 72/16; Ordinance on the Determination of Compensation for Transferred and Restricted Rights to Forests and Forest Lands. Official Gazette of the Republic of Croatia, Croatian Parliament: Zagreb, Croatia, 2016.

- Prpić, B. O vrijednosti općekorisnih funkcija šuma. Šumarski List 1992, 6–8, 301–312. [Google Scholar]

- Van Wagner, C.E.; Pickett, T.L. Equations and Fortran Program for the Canadian Forest Fire Weather Index System; Forestry Technical Report 33; Canadian Forestry Service, Government of Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 1985; p. 18.

- Dimitrov, T. Šumski požari i sistem procjene opasnosti od požara. In Osnove Zaštite Šuma od Požara; Centar za Informacije i Publicitet: Zagreb, Croatia, 1982; pp. 181–256. [Google Scholar]

- Cindrić, K.; Pasarić, Z. Modelling Dry Spells by Extreme Value Distribution with Bayesian Inference. In Meteorology and Climatology of the Mediterranean and Black Seas, Pageoph Topical Volumes; Vilibić, I., Horvath, K., Palau, J.L., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 171–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croatian Government. National Fire Protection Strategy for the Period from 2013 to 2022 (OG 68/13), Croatian Government. 2013. Available online: http://www.vlada.hr (accessed on 16 April 2023).

- Croatian Government. National Fire Protection Action Plan. 2013. Available online: https://vlada.gov.hr/UserDocsImages/2016/Sjednice/Arhiva/81.%20-%2012.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2023).

- Croatian Government. Report on the State of Fire Protection in the Republic of Croatia. 2022. Available online: https://vlada.gov.hr/sjednice/205-sjednica-vlade-republike-hrvatske-38059/38059 (accessed on 15 June 2023).

- Croatian Government. Program of Activities in the Implementation of Special Fire Protection Measures of Interest to the Republic of Croatia in Year 2023. Available online: https://hvz.gov.hr/program-aktivnosti/1788 (accessed on 16 April 2023).

- OG 51/12; Ordinance on the Fire Protection Plan. Official Gazette of the Republic of Croatia, Croatian Government: Zagreb, Croatia, 2012.

- OG 33/14; Ordinance on Forest Fire Protection. Official Gazette of the Republic of Croatia, Ministry of Interior: Zagreb, Croatia, 2014. Available online: https://narodne-novine.nn.hr/clanci/sluzbeni/2014_03_33_599.html (accessed on 15 June 2023).

- OG 30/09; Sustainable Development Strategy for Republic of Croatia. Official Gazette of the Republic of Croatia, Croatian Government: Zagreb, Croatia, 2009.

- OG 46/02; National Strategy for Environmental Protection. Official Gazette of the Republic of Croatia, Croatian Government: Zagreb, Croatia, 2002.

- OG 46/20; Climate Change Adaptation Strategy. Official Gazette of the Republic of Croatia, Croatian Government: Zagreb, Croatia, 2020.

- OG 118/18; Law on Environmental Protection. Official Gazette of the Republic of Croatia, Croatian Parliament: Zagreb, Croatia, 2018.

- OG 16/19; Law on Mitigation and Elimination of Consequences of Natural Disasters. Official Gazette of the Republic of Croatia, Croatian Parliament: Zagreb, Croatia, 2019.

- OG 72/17; National Strategy and Action Plan for Nature Protection 2017–2025. Official Gazette of the Republic of Croatia, Croatian Government: Zagreb, Croatia, 2017.

- OG 80/13, 15/18, 14/19; Law on Nature Protection. Official Gazette of the Republic of Croatia, Croatian Parliament: Zagreb, Croatia, 2019.

- OG 143/08; Biodiversity and Landscape Conservation Strategy and Action Plan. Official Gazette of the Republic of Croatia, Croatian Government: Zagreb, Croatia, 2008.

- OG 6/96; Convention on Biological Diversity. Official Gazette of the Republic of Croatia, Croatian Government: Zagreb, Croatia, 1996.

- Croatian Government. Regulation on Protected Areas. Available online: https://mingor.gov.hr/o-ministarstvu-1065/djelokrug/uprava-za-zastitu-prirode-1180/zakoni-i-propisi-1224/zasticena-podrucja-1240/1240, (accessed on 15 June 2023).

- OG 51/12; Rulebook on Fire Protection Plan. Official Gazette of the Republic of Croatia, Ministry of Interior: Zagreb, Croatia, 2012.

- OG 82/15,118/18; Law on Civil Protection System. Croatian Parliament: Zagreb, Croatia, 2018.

- OG 14/19, 98/19; Law on Sustainable Waste Management. Croatian Parliament: Zagreb, Croatia, 2019.

- OG 120/2003; National Forest Policy and Strategy 2003. Croatian Parliament: Zagreb, Croatia, 2003.

- OG 20/18 115/18, 98/19; Law on Agriculture Land. Croatian Parliament: Zagreb, Croatia, 2019.

- OG 108/95, 56/10; Law on Flammable Liquids and Gases. Croatian Parliament: Zagreb, Croatia, 2010.

- OG 92/14; Law on Roads. Croatian Parliament: Zagreb, Croatia, 2014.

- OG 70/17; Law on Explosive Materials and Production and Trade of Weapons. Croatian Parliament: Zagreb, Croatia, 2017.

- OG 79/07; Law on Dangerous Materials Transport. Croatian Parliament: Zagreb, Croatia, 2007.

- OG 118/18; Law on Air Protection. Croatian Parliament: Zagreb, Croatia, 2018.

- OG 70/17; Law on Safety and Interoperability of Railroad System. Croatian Parliament: Zagreb, Croatia, 2017.

- OG 47/19; Ordinance on Methodology for Monitoring the Condition of Agricultural Land. Ministry of Agriculture, Republic of Croatia: Zagreb, Croatia, 2019.

- Vučetić, V.; Anić, M. Agrometeorološki Atlas Hrvatske u Razdoblju 1991–2020. Povodom 70 Godina Agrometeorološke Službe u DHMZ-U; Državni Hidrometeorološki Zavod: Zagreb, Croatia, 2021; p. 241.

- Tomašević, I.Č.; Cheung, K.K.W.; Vučetić, V.; Fox-Hughes, P. Comparison of Wildfire Meteorology and Climate at the Adriatic Coast and Southeast Australia. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feist, O. Analiza Toplinskog Stresa za Potrebe Poljodjelstva u Hrvatskoj u Prošlim, Sadašnjim i Budućim Klimatskim Uvjetima, Diplomski Rad, Geofizički Odsjek Prirodoslovno-Matematičkog Fakulteta; Sveučilište u Zagrebu: Zagreb, Croatia, 2011; p. 53. [Google Scholar]

- Vučetić, V.; Ivatek-Šahdan, S.; Tudor, M.; Kraljević, L.; Ivančan-Picek, B.; Strelec Mahović, N. Analiza vremenske situacije tijekom kornatskog požara 30. kolovoza 2007. Hrvat. Meteorološki Časopis 2007, 42, 41–66. [Google Scholar]

- Ferina, J.; Vučetić, V. Ocjena Požarne Sezone u Hrvatskoj u 2017. Godini; Državni Hidrometeorološki Zavod: Zagreb, Croatia, 2018; p. 87.

- Tomašević, I.; Sviličić, P.; Vučetić, V. Ocjena Požarne Sezone u Hrvatskoj u 2014. Godini; Državni Hidrometeorološki Zavod: Zagreb, Croatia, 2015; p. 72.

- Fernandes, P.M. Fire-smart management of forest landscapes in the Mediterranean basin under global change. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2013, 110, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Rigo, D.; Libertà, G.; Houston Durrant, T.; Artés Vivancos, T.; San-Miguel-Ayanz, J. Forest Fire Danger Extremes in Europe under Climate Change: Variability and Uncertainty; EUR 28926 EN; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2017; ISBN 978-92-79-77046-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EURONEWS. There Three Times More Wildfires in the EU so far This Year. 2019. Available online: https://www.euronews.com/my-europe/2019/08/15/there-have-been-three-times-more-wildfires-in-the-eu-so-far-this-year (accessed on 6 October 2023).

- San-Miguel-Ayanz, J.; Durrant, T.; Boca, R.; Maianti, P.; LibertÀ, G.; Artes Vivancos, T.; Jacome Felix Oom, D.; Branco, A.; De Rigo, D.; Ferrari, D.; et al. and Nuijten, D. Advance Report on Wildfires in Europe, Middle East and North Africa 2021; EUR 31028 EN; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2022; ISBN 978-92-76-49633-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EURONEWS; Lenarčič, J. The European Commission for Crisis Management. 2023. Available online: https://www.euronews.com/my-europe/2023/01/11/wildfire-damages-cost-2-billion-last-year-says-eu-commissioner (accessed on 6 October 2023).

- Janota, J.J.; Broussard, S.R. Examining private forest policy preferences. For. Policy Econ. 2008, 10, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anić, M.; Bašić, J.; Vučetić, V. Meteorološka Analiza Opasnosti od Požara Raslinja u Hrvatskoj u 2021. Godini; Državni Hidrometeorološki Zavod: Zagreb, Croatia, 2021; p. 86.

- Barešić, D. Utjecaj Klimatskih Promjena na Potencijalnu Opasnost od Požara Raslinja u Hrvatskoj, Diplomski Rad, Geofizički Odsjek Prirodoslovno-Matematičkog Fakulteta; Sveučilište u Zagrebu: Zagreb, Croatia, 2011; p. 56. [Google Scholar]

- Viegas, D.X. Weather, fuel status and fire occurrence. In Predicting a Large Forest Fires; Moreno, J.M., Ed.; Backhuys Publishers: Leiden, The Netherlands, 1998; pp. 31–48. [Google Scholar]

- Mifka, B.; Vučetić, V. Vremenska analiza katastrofalnog šumskog požara na otoku Braču od 14. do 17. srpnja 2011. Vatrog. I Upravlj. Požarima 2012, 3, 13–25. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, D.M.; Rundel, P.W. Pine ecology and biogeography-An introduction. In Ecology and Biogeography of Pinus; Richardson, D.M., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1999; pp. 3–49. [Google Scholar]

- Leone, V.; Lovreglio, R.; Martinez Fernandez, J. Forest fires and anthropic influences: A study case (Gargano National Park, Italy). In IV International Conference on Forest Fire Research and Wildland Fire Safety, Coimbra, Portugal; electronic, edition; Viegas, D.X., Ed.; Millpress: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Bilandžija, J.; Lindić, V. Utjecaj strukture šumskog goriva na vjerojatnost pojave i razvoj požara u sastojinama alepskog bora. Radovi 1993, 28, 215–224. [Google Scholar]

- Stipaničev, D.; Bugarić, M.; Bakšić, N.; Bakšić, D. Fuel Moisture Content in Croatian Wildfire Spread Simulator AdriaFirePropagator; Advances in Forest Fire Research 2022, Domingos Xavier Viegas, Luís Mário Ribeiro (ur.); Imprensa da Universidade de Coimbra: Coimbra, Portugal, 2022; pp. 216–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Fire Risk | FWI | BUI | SSR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Very low | ≤4 | ≤48 | – |

| Low | 5–8 | 49–85 | <1 |

| Moderate | 9–16 | 86–118 | 1–3 |

| High | 17–32 | 119–158 | 3–7 |

| Very high | ≥33 | ≥159 | >7 |

| Regulation Area | Legislation | Measures and Activities |

|---|---|---|

| Sustainable development | Sustainable development strategy for Republic of Croatia [54] | − |

| Environmental protection | National strategy for environmental protection [55] | + |

| Climate change adaptation strategy [56] | + | |

| Law on Environmental Protection [57] | − | |

| Law on Mitigation and Elimination of Consequences of Natural Disasters [58] | + | |

| Nature protection | National strategy and action plan for nature protection 2017–2025 [59] | + |

| Law on Nature Protection [60] | − | |

| Biodiversity conservation | Biodiversity and landscape conservation strategy and action plan [61] | + |

| Convention on Biological Diversity [62] | − | |

| Protected areas | Rulebook on Protected Areas [63] | − |

| National strategy for fire protection 2013–2022 [64] | + | |

| Fire protection | Program of activities in the implementation of special fire protection measures of interest to the Republic of Croatia [51] National Fire Protection Action Plan [49] Law on Fire Protection [39] Law on Fire Fighters [40] Rulebook on fire protection plan [64] Law on Civil Protection System [65] | + |

| Waste management | Law on Sustainable Waste Management [66] | − |

| Forestry | National forest policy and strategy 2003 [67] Forest Law [38] Ordinance on Forest-Fire Protection [53] | + |

| Agriculture | Law on Agriculture Land [68] | + |

| Related laws | Law on Flammable Liquids and Gases [69] Law on Roads [70] Law on Explosive Materials and Production and Trade of Weapons [71] Law on Dangerous Materials Transport [72] Law on Sustainable Waste Management [66] Law on Air Protection [73] Law on Safety and Interoperability of Railroad System [74] | + |

| Year | First-Age Class (EUR) | Growing Stock Damage (EUR) | Non-Wood Forest Functions (EUR) | Number of Fires | Burned Area (ha) | Fire Protection (Mil. EUR) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2013 | n.a. | 1,832,227.24 | 6,912,529.86 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| 2014 | n.a. | 131,271.57 | 526,811.78 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| 2015 | 374,037.70 | 1,535,041.15 | 8,597,690.47 | 164 | 6594 | 8.9 |

| 2016 | 752,588.27 | 888,903.64 | 3,801,831.69 | 134 | 6707 | 3.8 |

| 2017 | 4,598,221.40 | 10,518,980.62 | 94,189,673.50 | 316 | 41,171 | 9.2 |

| 2018 | 518,582.43 | 141,226.44 | 2,056,809.13 | 49 | 1095 | 13.3 |

| 2019 | 1,936,421.56 | 757,499.34 | 4,056,145.47 | 118 | 1639 | 9.6 |

| 2020 | 544,730.55 | 5,174,807.54 | 176,964,693.39 | 141 | 20,874 | 8.0 |

| 2021 | 2,419,138.63 | 1,318,733.82 | 75,255,425.04 | 111 | 4328 | 8.3 |

| 2022 | 1,595,859.04 | 4,059,725.26 | 167,963.24 | 238 | 17,760 | 10.3 |

| Total | 8,724,581.90 | 20,979,957.53 | 297,106,185.29 | 1271 | 100,168 | 71.4 |

| Years | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maximal Number of Consecutive Days | ||||||||

| tmax ≥ 30 °C | 45 | 18 | 47 | 24 | 39 | 41 | 32 | 25 |

| tmax ≥ 32 °C | 10 | 0 | 35 | 17 | 15 | 20 | 15 | 10 |

| P ≤ 0.5 mm | 57 | 34 | 51 | 34 | 73 | 37 | 49 | 37 |

| P < 1.5 mm | 81 | 54 | 56 | 41 | 78 | 39 | 51 | 39 |

| P < 2.8 mm | 102 | 55 | 84 | 42 | 100 | 50 | 78 | 50 |

| Variable | Correlations (Fires) Marked Correlations Are Significant at p < 0.05000 N = 8 (Casewise Deletion of Missing Data) | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Means | Std.Dev. | I Age Class (EUR) | Growing Stock Damage (EUR) | Non-Wood Forest Functions (EUR) | Total Damage (EUR) | Number of Fires | Area (ha) | Burnt Area Indicator (ha/fire) | Share of Fires (%) | Sources Fire Protection (Mil. €) | tmax > 30 °C | tmax > 32 °C | P < 0.5 mm | P < 1.5 mm | P < 2.8 mm | |

| I age class (EUR) | 1,592,447 | 1,428,146 | 1.000 | 0.712 | 0.225 | 0.275 | 0.689 | 0.669 | 0.320 | −0.0423 | 0.043 | 0.154 | −0.360 | −0.003 | 0.380 | 0.387 |

| Growing stock damage (EUR) | 3,049,290 | 3,484,688 | 0.712 | 1.000 | 0.578 | 0.624 | 0.871 | 0.994 | 0.852 | −0.014 | −0.009 | −0.013 | −0.295 | −0.439 | −0.091 | −0.149 |

| Non-wood forest functions (EUR) | 45,636,279 | 64,696,326 | 0.225 | 0.578 | 1.000 | 0.998 | 0.203 | 0.553 | 0.819 | 0.228 | −0.159 | −0.309 | −0.563 | −0.177 | 0.020 | −0.025 |

| Total damage | 50,278,016 | 67,151,445 | 0.275 | 0.624 | 0.998 | 1.000 | 0.255 | 0.599 | 0.840 | 0.218 | −0.153 | −0.295 | −0.565 | −0.194 | 0.023 | −0.024 |

| No. of fres | 159 | 83 | 0.689 | 0.871 | 0.203 | 0.255 | 1.000 | 0.882 | 0.620 | −0.167 | −0.119 | 0.084 | −0.010 | −0.297 | 0.007 | −0.075 |

| Area (ha) | 12,521 | 13,644 | 0.669 | 0.994 | 0.553 | 0.599 | 0.882 | 1.000 | 0.867 | −0.035 | −0.058 | −0.055 | −0.279 | −0.420 | −0.099 | −0.157 |

| Burnt area indicator (ha/fire) | 65 | 50 | 0.320 | 0.852 | 0.819 | 0.840 | 0.620 | 0.867 | 1.000 | −0.010 | −0.187 | −0.326 | −0.417 | −0.370 | −0.168 | −0.230 |

| Share of fires (%) | 79 | 11 | −0.042 | −0.014 | 0.229 | 0.218 | −0.167 | −0.035 | −0.010 | 1.000 | 0.069 | 0.610 | 0.414 | −0.115 | 0.114 | −0.052 |

| Sources fire protection (Mil. €) | 9 | 3 | 0.043 | −0.009 | −0.159 | −0.153 | −0.119 | −0.058 | −0.187 | 0.069 | 1.000 | 0.597 | 0.157 | −0.570 | −0.389 | −0.502 |

| tmax > 30 °C | 35 | 8 | 0.154 | −0.013 | −0.309 | −0.295 | 0.084 | −0.055 | −0.326 | 0.610 | 0.597 | 1.000 | 0.703 | −0.382 | −0.078 | −0.283 |

| tmax > 32 °C | 18 | 7 | −0.360 | −0.295 | −0.563 | −0.565 | −0.010 | −0.279 | −0.417 | 0.414 | 0.157 | 0.703 | 1.000 | −0.296 | −0.299 | −0.441 |

| P < 0.5 mm | 49 | 18 | −0.003 | −0.439 | −0.177 | −0.194 | −0.297 | −0.420 | −0.370 | −0.115 | −0.570 | −0.382 | −0.296 | 1.000 | 0.863 | 0.910 |

| P < 1.5 mm | 62 | 28 | 0.380 | −0.091 | 0.020 | 0.023 | 0.007 | −0.099 | −0.168 | 0.114 | −0.389 | −0.078 | −0.299 | 0.863 | 1.000 | 0.935 |

| P < 2.8 mm | 73 | 28 | 0.387 | −0.149 | −0.025 | −0.024 | −0.075 | −0.157 | −0.230 | −0.052 | −0.502 | −0.283 | −0.441 | 0.910 | 0.93 | 1.000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Posavec, S.; Barčić, D.; Vuletić, D.; Vučetić, V.; Čavlina Tomašević, I.; Pezdevšek Malovrh, Š. Forest Fires, Stakeholders’ Activities, and Economic Impact on State-Level Sustainable Forest Management. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16080. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152216080

Posavec S, Barčić D, Vuletić D, Vučetić V, Čavlina Tomašević I, Pezdevšek Malovrh Š. Forest Fires, Stakeholders’ Activities, and Economic Impact on State-Level Sustainable Forest Management. Sustainability. 2023; 15(22):16080. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152216080

Chicago/Turabian StylePosavec, Stjepan, Damir Barčić, Dijana Vuletić, Višnjica Vučetić, Ivana Čavlina Tomašević, and Špela Pezdevšek Malovrh. 2023. "Forest Fires, Stakeholders’ Activities, and Economic Impact on State-Level Sustainable Forest Management" Sustainability 15, no. 22: 16080. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152216080

APA StylePosavec, S., Barčić, D., Vuletić, D., Vučetić, V., Čavlina Tomašević, I., & Pezdevšek Malovrh, Š. (2023). Forest Fires, Stakeholders’ Activities, and Economic Impact on State-Level Sustainable Forest Management. Sustainability, 15(22), 16080. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152216080