Abstract

The purpose of this study is to conduct an in-depth needs analysis in order to create a sustainable business English course. Drawing critical insights from the development and implementation of a sustainable curriculum, a mixed-methods approach was carried out that involved data collected via a structured questionnaire administered to 117 university students of business administration and accounting. The findings indicated that a substantial majority of respondents perceived their level of English language proficiency to be low, with merely 25% evaluating their English skills as either “good” or “excellent”. Several language skills such as speaking, listening, and writing were recognized as communicative needs for effective business communication and studies, with over 86% interested in registering for the course. Regarding pedagogical needs, the emergence of preferences for face-to-face teaching, making the course mandatory, varying perspectives regarding the frequency and duration of courses, and inclination towards small group learning were established. For the sustainability of the business English course, this study suggests an integrated, responsive, and adaptive course that emphasizes interactive learning and curriculum alignment with global business trends.

1. Introduction

English communication skill has become crucial in today’s interconnected global economy. Ref. [1] emphasizes the significance of this skill in fostering cross-cultural understanding, fostering international partnerships, and enabling efficient communication in diverse business environments. The author suggests that business English courses should equip learners with linguistic skills and cultural knowledge to navigate international business dynamics effectively. Thus, academic institutions worldwide have responded to the demands of this phenomenon by integrating business English courses into their curricula. Ref. [2] found that these courses integrate cross-cultural communication, negotiation strategies, and international business etiquette for both local and global contexts. Ref. [3] emphasizes the importance of business English proficiency in improving students’ employability and readiness for the global market. The inclusion of these courses is a strategic decision to equip students with the essential skills needed for success in the field of international business.

Many faculties of business administration face the challenge of maintaining the relevance and effectiveness of their curricula [4]. Ref. [5] emphasizes the importance of conducting a comprehensive needs analysis for delivering personalized, sustainable and efficient instruction. This analysis ensures that the curriculum is in line with the authentic requirements of students, industry expectations, and the ever-changing global business terminology. Ref. [6] defines a needs analysis as a systematic evaluation of students’ educational needs in order to determine the specific learning outcomes they should achieve by the end of a particular course. In the field of business English, the integration of the present situation analysis (PSA), communicative needs analysis (CNA), and pedagogical needs analysis (PNA) has enhanced the target situation analysis (TSA) approach, enabling the development of comprehensive business English courses. According to [7], the PSA is used to assess learners’ current proficiency level, providing educators with information about their initial starting point. Also, the inclusion of the CNA, as described by [8], enhances the curriculum by focusing on the specific communication tasks and contexts that learners will need in their academic and professional domains. This ensures that the content of the curriculum is relevant. Then, the PNA conducts an evaluation of the most effective approaches for bridging the gap between the PSA and desired goals, as suggested by [9]. By incorporating these three analyses into the task-based syllabus approach (TSA), business English courses can be tailored to cater to learners’ specific requirements. This approach effectively addresses their current linguistic shortcomings and equips them with the necessary language skills for their future professional and academic endeavors. The procedure mentioned above is crucial in ensuring that the course content, methodology, and resources align with the specific linguistic and cultural requirements of learners in business settings.

The challenges related to creating an effective business English program go beyond just designing a curriculum. According to ref. [10], educators should prioritize the sustainability of the business English course by regularly integrating feedback and insights gathered from a needs analysis conducted with business companies, language institutions, and students. This proactive approach allows educators to anticipate changes in business communication trends, enabling the course to adapt effectively to global market trends. Ref. [11] defines sustainability as a continuous process of improving innovations over a suitable timeframe to adapt to existing or new circumstances. This paper primarily examines the continuous adaptation of an innovation to dynamic contexts [12]. The concept of course sustainability highlights the significance of maintaining long-term relevance through adaptability in response to evolving educational landscapes. Ref. [12] states that sustainable courses are designed to align with current educational objectives and adapt to changing societal needs. Ref. [13] argues that a sustainable course framework prioritizes the continuous improvement of instructional methods, incorporating feedback mechanisms to align with standards and changing student demographics.

2. Context of Study

Our university in southern Chile aims to cultivate global citizenship among students by emphasizing the importance of effective cross-cultural communication and recognizing the interconnectedness of the modern world. Introducing a business English course into the department of business administration is a strategic decision aimed at equipping students with the necessary linguistic and cultural competencies for engaging in the global business environment. One of our university’s educational models is to address the learning needs of our students, aiming to promote their academic success and overall satisfaction with their educational experience. Insufficient fulfilment of these needs may result in student disengagement, which can subsequently lead to reduced persistence and overall retention in a course or program. Ref. [4] asserts that inadequate academic and social integration within educational institutions increases the likelihood of student attrition, which can subsequently jeopardize the sustainability of the course in the long run.

In the development of our business English curriculum, we recognize that the primary objective of language instruction is to enhance learners’ communicative proficiency in the target language. In order to enhance learners’ proficiency in using the target language in different contexts, including business settings, it is crucial to prioritize and integrate the four language skills from the outset. This approach ensures that learners are exposed to situations and language requirements that closely resemble real-life scenarios [14]. We have implemented a model in which business English learners receive language input through listening and/or reading activities, followed by speaking or writing tasks based on the material they have encountered. The suggested business English program emphasizes listening and reading as the primary skills, while speaking and writing are considered essential for effective communication [15]. The students primarily engage in PowerPoint presentations on business-related topics, such as products and services, project design, and the CEO’s profile, to facilitate business–corporate communication. Business English courses are categorized into two levels, the basic level (A1, A2) and intermediate level (B1, B2), based on the common European framework of languages (CEFR) to accommodate students with varying levels of English proficiency. The course is mandatory for students and is instructed by non-native English speakers on a thrice-weekly basis. The course program has experienced a low retention rate over the past two years. One possible explanation for this phenomenon is a lack of motivation among students. Foreign language learning is influenced by both internal and external factors. Internal factors include preferred learning style and preferred language-learning skills. External factors include preferred class duration, preferred type of teacher, and preferred mode of learning [16]. If the issue persists in the coming year, then it is likely that the course will be discontinued.

Although there is ample documentation on the initial implementation of business English courses using a needs analysis, there is a noticeable lack of research investigating the significance of a needs analysis in guaranteeing the sustainability of a business English course within a constantly changing global business landscape. To address the existing void in the scholarly literature, the present study aims to conduct a comprehensive needs analysis pertaining to the sustainability of the business English course (BEC). This entails employing a mixed methodology to evaluate and harmonize the PSA with its intended communicative and professional requirements (CNA), as well as its pedagogical demands (PNA). This study aims to offer recommendations to English educators and policymakers on how to develop and sustain the effectiveness of their business English curriculum. This paper commences by outlining the design of the theoretical and conceptual framework. It then proceeds to conduct a comprehensive review of the relevant literature, followed by a detailed description of the methodology employed. Subsequently, the paper presents the obtained results and engages in a thorough discussion of their implications. Finally, the conclusion provides a concise summary of the findings and offers critical evaluations.

3. Conceptual Framework

Our contention is that the sustainability of a business English Course relies on its capacity to meet the present and future requirements of its learners, within the ever-changing context of global business communication. The integration of the present situation analysis (PSA), communicative needs analysis (CNA), and pedagogical needs analysis (PNA) assumes a crucial role within the framework of the target situation analysis (TSA). PSA offers valuable information regarding the current language competencies of learners, serving as a basis for assessing progress and identifying areas for improvement. CNA, however, evaluates the particular communicative situations and demands that learners may encounter in future professional and current educational environments. This process guarantees that the content of the course is not only theoretically robust but also relevant in practical terms. The focus of PNA is on the implementation of teaching methods and materials, with the aim of modifying them to align with the preferences and abilities of the learners, as well as the changing trends in language pedagogy. When implemented comprehensively within the TSA framework, these analyses guarantee that the business English Course maintains its relevance in the current business environment and is adaptable to evolving linguistic and communicative requirements. Therefore, it is crucial to prioritize the integration of a comprehensive approach in the design of the course in order to maintain its sustainability and ongoing relevance [8,17].

4. Literature Review

Within academic discourse, the terms “course sustainability” and “curriculum sustainability” are frequently employed synonymously. One of the studies of course sustainability includes the adoption of three key criteria for assessing the sustainability of a course. This includes relevance, quality, and financial viability [18]. The authors claim relevance is crucial in ensuring that there is alignment between a current and future need for a course in industry or academia. While quality is seen to be key to students’ engagement, which is influenced by both content and teaching methods, the financial viability involves evaluating the long-term sustainability of the course by comparing expenses and income [18]. On the other hand, [19] argued that the goal of a sustainable course is to equip students with extensive knowledge to enable them to make well-informed decisions that encompass various dimensions such as environmental, social, cultural, and economic aspects. The implementation of such empowerment has been demonstrated in various course programs, such as the life science information literacy program [20], hybrid online laboratory course [21], and service-learning program [22].

The needs analysis plays a crucial role in the development of business English courses by systematically identifying and addressing requirements. Ref. [23] conducted a study aimed at creating a business English curriculum for students seeking careers in companies involved in international business transactions. The study emphasized the significance of prioritizing writing and speaking skills, as these are the primary modes of communication through email and telephone calls, respectively. In a separate study, the effectiveness of needs analysis was examined by administering a questionnaire to explore three components: present situation analysis (PSA), learning situation analysis (LSA), and target situation analysis (TSA). The assessment of students’ language proficiency, learning preferences, and motivations for learning relied on these components. Ref. [24] emphasized the importance of adapting the curriculum to meet students’ individual needs in order to improve learning outcomes. A recent needs analysis conducted in Albania for the business English certificate has highlighted the importance of revising syllabi to incorporate the changing skills required in the business field. Ref. [25] conducted a study that explored the intricacies of teaching business English and the evolving demands of the job market. Another study conducted in the Chinese context integrated the concept of identity as an essential element in the needs analysis framework among business English students [26]. It was revealed that the convergence of various identities, such as professional, gender, cultural, and student identities, directly affects the acquisition of business English skills. This adds complexity to the task of designing customized business English courses. Regarding the types of learners of business English, ref. [27,28] identified English for general business purposes (studying without focusing their attention on a certain segment of business), business English for specific purposes (for groups of professionals who focus their attention on their own field of work), and business English for academic purposes (studying with a concentration on a certain segment of business such as accounting, marketing, money and banking, international trade, and business law). The best type of profile to teach business English is businessmen and women with English teaching qualifications [29]. However, the authors argue that the effectiveness of business English teachers is contingent upon their capacity to comprehend their students’ identities, learning strengths and weaknesses, and the factors that facilitate their language development.

The aforementioned studies collectively emphasize the significance of conducting a needs analysis to effectively design a business English course with a practical application in higher education. However, it is worth noting that insufficient consideration has been given to the sustainability of the course. Therefore, the primary inquiries of this investigation are as follows:

- How does the present situation of a business English course influence the sustainability of the course?

- How does the communicative need of a business English course influence the sustainability of the course?

- How do pedagogical needs influence the sustainability of the course?

5. Methodology

5.1. The Research Design

This research aims to conduct a needs analysis to enhance the sustainability of a business English course. The study adopts a mixed-methods research approach, following the systematic framework outlined by [30]. According to Ref. [30], closed- and open-ended questionnaires are commonly employed in mixed-methods research for data collection purposes. It is argued that closed-ended questions are structured and lend themselves to quantitative analysis, making them useful for examining trends, patterns, and statistical relationships. On the other hand, open-ended questions are commonly employed in qualitative research to gather textual data that can be thematically analyzed, allowing for a deeper exploration of participants’ experiences, perceptions, and perspectives.

The business English course’s needs analysis involved 117 university’s students from the business administration and accounting department in the southern part of Chile. This group exhibited a diverse demographic composition. Males comprised a slight majority, with 60 participants (56.6%), while females accounted for 56 individuals (52.8%). Furthermore, one participant, constituting 0.9% of the total sample, self-identified as belonging to a category other than those specified. The diverse representation allowed for a wide range of perspectives, which is crucial for conducting a thorough needs analysis in the field of business English [31].

5.2. Questionnaire

Before initiating the design, an exhaustive review of the pertinent literature was conducted. This review helped identify established frameworks and models that have previously been used for similar purposes. For instance, the work of ref. [17] on target situation needs analysis provided a foundational understanding of the objectives behind such analyses, emphasizing the importance of aligning them with specific situational demands.

The present situation analysis (PSA), communicative needs analysis (CNA), and pedagogical needs analysis (PNA) assume a crucial role within the framework of target situation analysis (TSA). PSA offers valuable information regarding the current language competencies of learners, serving as a basis for assessing progress and identifying areas for improvement. CNA, however, evaluates the particular communicative situations and demands that learners may encounter in future professional and current educational environments. This process guarantees that the content of the course is not only theoretically robust but also relevant in practical terms. The focus of PNA is on the implementation of teaching methods and materials, with the aim of modifying them to align with the preferences and abilities of the learners, as well as the changing trends in language pedagogy.

Based on the literature, essential dimensions of the questionnaire were identified. As presented in Appendix A, Mayr et al.’s [32], West’s [8], Yulia et al.’s [33], and Lasekan et al.’s [34] taxonomies, which differentiated between the current language competencies of learners’ target needs (PSA) and communicative needs of learners (CNA), each offered a clear implementation of teaching methods (PNA). This differentiation ensured that the questionnaire would not only gauge their linguistic competence but also how they best learn and what they wish to improve.

The questionnaire’s specific items were then crafted, inspired by the insights and parameters laid out in the literature. For example, items about the number of hours, choice of teachers, and mode of learning were inspired by real scenarios obtainable in our university. Ref. [34] provides insights into assessing the importance of reading, listening, speaking, vocabulary, and writing skills, thereby ensuring the questionnaire would tap into the critical skills needed in the business world.

The deliberate intermingling of items, despite the segmented structure, aims to reduce response bias [35]. It is hypothesized that respondents may unintentionally perceive a pattern when items are presented in a predictable or logical sequence. This may result in respondents’ answers being influenced by the perceived order rather than their authentic beliefs, emotions, or experiences [36]. To enhance the reliability of the collected data, we aim to mitigate predictable patterns by interspersing items within sections. This approach encourages respondents to evaluate each item independently.

To ensure data precision, our questionnaire incorporates various response scales to assess the PSA, CNA, and PNA. The Likert scale measures learners’ perception (e.g., “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree”, “basic to excellent”, “never to always”, and “not important to very important”), while nominal scales capture categorical data (e.g., “yes-no”). Subscale scores are computed as simple averages and transformed into a 1–5 scale, with high values representing a high degree of perception and vice versa. This diversity aligns with best practices in survey design [37].

To elicit diverse perspectives and explore the depth of participants’ viewpoints, an open-ended question is included in the fifth section of the instrument. Participants were requested to provide feedback on the business English course. The purpose of asking clear and concise questions is to ensure that the responses obtained encompass all possible answers to our research questions.

To ensure broad comprehension of the research instrument, a Spanish translation of the questionnaire was provided to all participants. Given the complex and nuanced nature of linguistic translation, particularly in the context of research, it was essential to prioritize clarity and accuracy during the translation process. To ensure the questionnaire’s reliability, collaboration with an experienced linguist who specialized in translating between Spanish and English was initiated. The translator had extensive experience in translating academic research, which ensured that the translated version maintained the nuances, tone, and specificity of the original document. To ensure translation accuracy and fidelity, a back-translation procedure was implemented [38]. Following the initial translation from English to Spanish, a separate expert, who was unaware of the original English version, translated the questionnaire back into English. This widely recommended method in cross-cultural research allows for a comparison between the original and back-translated versions to identify and correct any potential discrepancies. Prior to its official deployment, the translated questionnaire was subjected to a pilot test involving a limited number of bilingual participants who were in the last year of an English pedagogy program. The participants were chosen because their advanced level of English is internationally certified. Their bilingual skills allowed them to give feedback on the clarity, coherence, and appropriateness of the translated items. Their insights were instrumental in making minor adjustments to ensure that the translated version resonated authentically with the target demographic. The importance of piloting, as highlighted in the literature [39], was then used as a guide. Piloting ensures that the questions are understood as intended, that there are no ambiguities, and that the questionnaire’s length and format are appropriate. Feedback from the pilot was then compared with the original frameworks and models to ensure alignment. The iterative process of refining the questionnaire, based on feedback and ongoing literature consultation, ensured that the finalized instrument remained firmly rooted in scholarly insights. Once the questionnaire was finalized, additional studies were consulted. This helps researchers to identify existing scales or items that have similar constructs. In other words, it facilitates the possibility of conducting validation studies to compare the new questionnaire with existing measures.

6. Data Collection

This study employed convenience sampling due to its cost-effective nature and the accessibility of subjects to the researcher. This method involves choosing participants who are easily available without considering their distribution in the population [40]. Email invitations containing a direct link to the survey were sent out to potential participants. This approach ensured that the participants could access the survey at their convenience. A follow-up reminder email was dispatched after one week to motivate those who had not yet responded, thereby aiming to enhance the overall response rate. Participants were provided with a two-week timeframe to complete the survey, offering them ample flexibility. To ensure a higher response rate, regular reminders were sent out, gently nudging participants to fill out the survey if they had not already. This not only emphasized the importance of their input but also catered to those who might have forgotten or overlooked the initial invitation. This digital approach facilitated easy distribution and quick response times. The platform allowed for the real-time tracking of responses and streamlined data collection.

Ethical Considerations

Online surveys have the advantages of being easily accessible and having a wide reach [41], but they also raise ethical concerns [42]. Informed consent was given priority from the beginning. Participants received an information sheet that outlined the study’s objectives, their role in the study, and guarantees of confidentiality and anonymity. Participants were also provided with information regarding their right to voluntarily withdraw from the study without facing any negative consequences. To ensure data protection, the survey platform used adhered to data protection regulations, implementing encryption and secure data storage in the online context. Participants’ responses were coded to ensure anonymity and protect their identity by removing or altering any potentially identifiable information.

7. Data Analysis

Upon completion of data collection, the first step was to engage in an initial data screening. This meticulous process was aimed at ensuring that the dataset was clean and free from any anomalies [43]. Each entry was checked for consistency to ascertain that respondents’ answers adhered to the expected response formats [44]. Outliers, which are extreme values that deviate significantly from other observations, were identified and decisions were made on whether to retain, transform, or remove them, depending on their impact on the overall analysis. After ensuring the dataset’s cleanliness, the analysis proceeded with computing descriptive statistics using IBM SPSS software version 25. This phase involved generating measures of frequency distributions, and percentages were computed to understand the data’s characteristics better. Subsequent to the descriptive analysis, the findings were methodically parsed and interpreted in light of the research questions. This phase involved juxtaposing the empirical data with the theoretical frameworks and expectations posited in the literature review. To help in the interpretation and presentation of the results, various graphical representations like histograms, pie charts, and bar charts were generated. These visual aids not only provided a clearer picture of the data distribution but also facilitated a more intuitive understanding of the findings for both the researchers and the intended audience. The qualitative data analysis protocol for an open-ended questionnaire comprises several essential steps. Initially, the responses are transcribed or recorded. Next, a thematic analysis is conducted to identify recurring themes, patterns, and variations in the textual data. Text segments are assigned codes and then categorized into broader themes [45]. Lastly, regular team meetings are conducted to promote intercoder reliability.

8. Results and Discussion

8.1. Socio-Demographic Profile

As shown in Table 1, a diverse group of participants was investigated for the needs analysis of the business English course. The survey respondents were predominantly male, comprising 51.3% of the sample, with females making up a close second at 47.9%. Only 0.8% of the participants identified themselves as belonging to non-binary gender categories. The majority of participants (87.2% of the sample) were enrolled in the field of business administration. In contrast, 12.8% of the respondents were pursuing a career in public accounting and auditing. The analysis of the data for the current academic year reveals that the majority of students are enrolled in the first and third years, accounting for 38.5% and 40.2% of the total student population, respectively. The sample included second-year students (8.5% of the total), fourth-year students (11.1%), and fifth-year students (1.7%). These data provide valuable insights into the demographic distribution of students who may benefit from a business English course.

Table 1.

Socio-demongraphic profile of the participants.

8.2. Present Situation Analysis (PSA)

Considering the current level of English proficiency of the learners, our results presented in Table 2 showed that only 25% of participants rated their English proficiency as “excellent” or “good”. This was also a recurring theme in participants’ responses. For example, one participant stated that “Learning English can be difficult but never impossible”. This discovery has important implications for the sustainability of the business English course. For example, the limited number of students who consider themselves highly proficient in English can be seen as having both positive and negative consequences. On one hand, it indicates a potential need for the course, as there is a noticeable requirement for improvement among a significant number of students. This requirement may impact student enrollments as individuals seek to improve their language skills. Furthermore, this suggests that course designers and educators have a specific duty to improve the overall English proficiency of a substantial portion of their students. In other words, the sustainability of a course is jeopardized when the course content and instructional approaches fail to cater to a wider range of students who may have basic English language skills. Moreover, a course primarily designed for advanced students may deter beginners or those at an intermediate level from enrolling or continuing in the course, thereby affecting both retention rates and the course’s overall reputation. However, minority students who rate their skills as “excellent” or “good” are likely to have unique expectations and requirements. If the course does not offer advanced modules or opportunities for students to improve their skills, then there is a risk of students’ disengagement.

Table 2.

Perceived level of English proficiency.

8.3. Perceived Level of English Skills

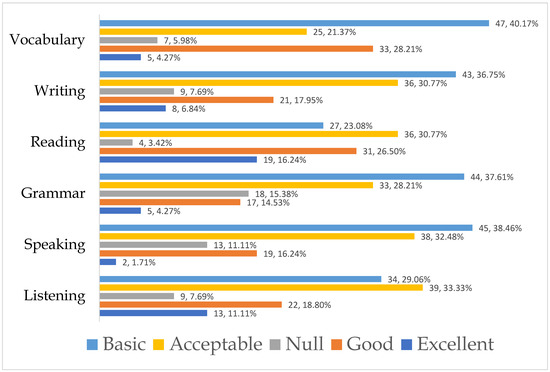

The needs analysis for a business English course revealed that few participants perceived their English proficiency’s level to be good or excellent. As shown in Figure 1 it becomes apparent that the matter at hand is not simply a general sense of inadequacy in English language proficiency, but rather a more precise concern that encompasses multiple language skills, such as grammar (22%), vocabulary (37%), reading (50%), writing (29%), and speaking (21%).

Figure 1.

Perceived level of English skills.

For a course to be deemed sustainable, it must maintain its relevance and consistently meet the needs of the learners. The prevalence of significant deficiencies in English skills among the majority of students who opt for a business English course poses both challenges and opportunities. Insufficiently addressing these needs may lead to increased attrition rates. Ref. [42] found that students may feel overwhelmed or perceive a lack of attention to their foundational needs in the course. This perception may affect the sustainability of the course.

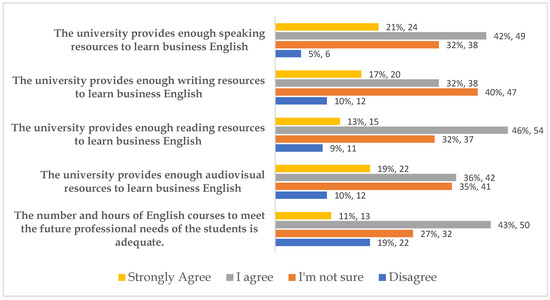

8.4. Perceived Level of Available Resources for Teaching the Course

As revealed in Figure 2, 54% of participants believe that the allocated instructional hours for learning the course are sufficient. This observation highlights a potential concern that may impact the long-term sustainability and efficacy of the course. A potential reason for perceiving the course duration as insufficient by 46% could be a misalignment between the learner’s expectations and the course delivery. The presence of this mild discrepancy can be ascribed to various factors. Learners may find the course material too complex to cover thoroughly within the allotted time, or they may desire more practical exercises and real-world applications to enhance their learning [46]. The sustainability of a course depends on achieving a balance between the amount of content covered and the time required for delivery. Poorly timed courses can lead to rushed completion of modules, reduced student engagement, and ultimately, compromised educational outcomes. Ref. [47] suggest that students’ performance may suffer when they consistently face time constraints, which can result in feelings of being rushed or an inability to understand course materials. Over time, this phenomenon may decrease student enrollment in the course, impacting its long-term sustainability.

Figure 2.

Perceived level of available resources for teaching the course.

Nevertheless, the participants attest to the fact that the university prioritizes the teaching and learning of English. This is another predominant theme in this study. According to a subject, “I’m glad that the university cares about English”. Mixed-methods research in this regard provided a comprehensive understanding of the significance of English within the university context and identified necessary measures for enhancing the quality of English.

8.5. Communicative Needs Analysis

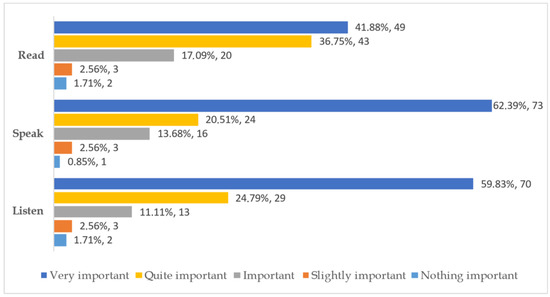

Regarding the level of importance of language skills, Figure 3 depicts that learners prioritize specific language skills, such as speaking (82%), listening (85%), and reading (79%), as being crucial for learning the course. This perspective offers a valuable framework for assessing the sustainability of the business English course.

Figure 3.

Level of importance of language skills.

Understanding the language skills that students consider important is essential for ensuring that the business English course remains relevant, effective, and aligned with the goals of its stakeholders. In today’s business environment, proficiency in effective verbal communication, listening comprehension, and business writing is necessary. When a specialized course, such as business English, aligns with specific requirements, it increases its perceived value and practicality in real-world contexts.

Therefore, to prioritize the development of speaking, listening, and reading skills, it is crucial for the course curriculum, teaching methodologies, and assessment strategies to be aligned accordingly. Ref. [48] found that courses that regularly adapt their content and structure based on needs analysis findings are more likely to achieve sustained learning outcomes. This, in turn, guarantees the sustained enrollment and provision of educational offerings by the institution.

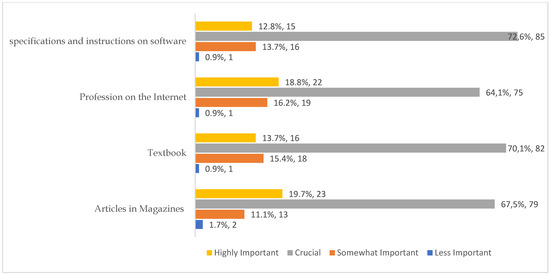

- Activities for which reading skill is necessary:

Figure 4 focuses on the usage of reading skill, which the majority believes is needed for understanding business textbooks (83%), business research articles (86%), and online resources pertaining to business topics (82%). The increased focus on purposeful reading not only addresses the current requirements of business education learners, but also provides valuable insights into the long-term sustainability of business English courses.

Figure 4.

Activities for which reading skill is necessary.

This study’s findings suggest that many participants value reading in specific contexts. This observation emphasizes the importance of learners recognizing the need to develop skills in understanding information from both traditional sources like textbooks and research articles, as well as from the constantly evolving and dynamic content found on the internet [49].

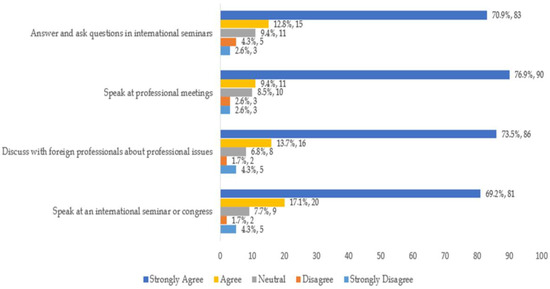

- Activities for which speaking skill is necessary:

As outlined in Figure 5, the usefulness of speaking skill was analyzed. The situations encompass effective communication in professional meetings, prioritized by 83% of respondents, and engaging in conversations with foreign colleagues and business professionals, highlighted by 86% of participants. The analysis emphasized the significance of proficient oral communication abilities in the current corporate landscape. This was also consistently acknowledged by the participants. One of them argued for the establishment of an interesting business conversation that would be useful for their profession in the future. This is because business involves communication, negotiation, and collaboration, often in multicultural settings. Therefore, it is essential to have the ability to effectively convey ideas and understand nuances when participating in professional meetings or interacting with colleagues from diverse cultural backgrounds [39]. Acquiring a high level of skill can lead to improved clarity in business transactions, reduced miscommunication, and stronger professional connections across international borders.

Figure 5.

Activities for which speaking skill is necessary.

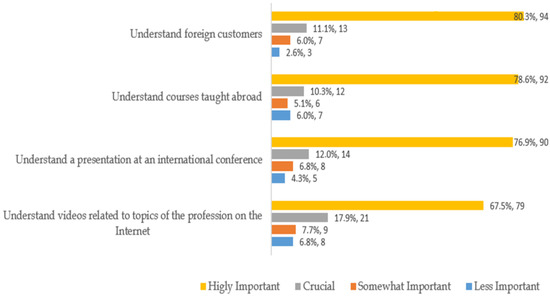

- Activities for which listening skill is necessary:

According to Figure 6, more than 80% of the participants strongly believe that having proficient listening skills is essential for understanding foreign customers, comprehending English language business videos, and grasping presentations in international settings. The importance of the listening skill in business contexts requires a detailed analysis, especially when considering the long-term effectiveness of the business English course. In the business domain, misunderstandings or misinterpretations can lead to substantial repercussions, including missed opportunities, contractual mistakes, or strained international relations. The participants unanimously agreed on the importance of listening skills, which is consistent with the essential role they play in effective international business engagements [50].

Figure 6.

Activities for which listening skill is necessary.

8.6. Level of Interest in Business English Courses

The latest findings from the needs analysis of the business English course show a significant level of interest (see Table 3), with 86% of participants expressing a strong desire to enroll in the course. The high level of interest observed in the course indicates its perceived relevance and potential for long-term sustainability. Examining this observation and establishing its correlation with the sustainability of the business English course offers a multifaceted perspective. Firstly, the high level of interest in the business English course reflects its recognized importance in the current global business environment. English, often called the “lingua franca” in the business world, plays a crucial role in enabling international transactions, negotiations, and collaborations. The growing presence of international business activities requires a greater focus on effective English communication, especially in professional settings. The demand of the course suggests that learners view it as a valuable asset in their professional skills [51]. Thus, the high level of interest in the course has various potential benefits.

Table 3.

Level of interest in business English course.

8.7. Reasons to Study Business English

Learners are primarily motivated to study business English due to the findings of the needs analysis. As shown in Table 4, the participants highlighted three key factors: the pursuit of scholarships for international postgraduate programs (21%), the motivation to build a successful professional future (16%), and the goal of achieving academic excellence in their studies (21%). Analyzing the underlying motivations and their relationship to the sustainability of the business English course provides a comprehensive exploration of the perceived value and long-term viability of the course.

Table 4.

Reasons to study business English.

The pursuit of scholarships for international postgraduate programs reflects the global recognition of the significance of English language proficiency. Many prestigious international universities prioritize high English language proficiency as a prerequisite for admission. Ref. [52] argues that a business English course should be seen as more than just an academic endeavor. Instead, it should be considered a strategic effort to achieve broader educational and professional goals. Also, effective communication is essential for achieving a successful career. In today’s business world, it is crucial to possess strong skills in expressing ideas, understanding complex information, and navigating cultural diversity. The inclusion of the business English course reflects the acknowledgment by participants that proficiency in English can lead to various career opportunities, both domestically and internationally [53].

When examining the implications of these motivations for the course’s sustainability, it becomes evident that the perceived benefits of the business English course go beyond immediate academic goals. The course facilitates the connection between individuals and their broader aspirations, highlighting its undeniable importance. Courses with perceived value typically have high enrollment rates, institutional support, and positive feedback, which enhances their long-term sustainability.

9. Pedagogical Needs Analysis (PNA)

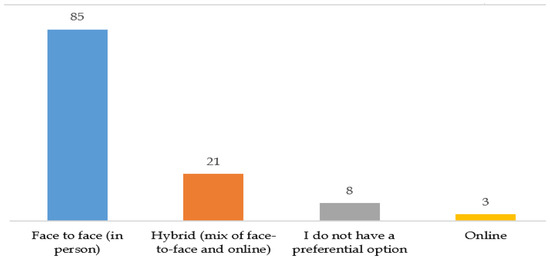

9.1. Preferred Mode of Learning

As highlighted in Figure 7, the majority of participants (85% of the sample) showed a strong preference for in-person instruction in their business English classes. This preference offers valuable insights, especially when examined in terms of course sustainability. Traditionally, face-to-face instruction has been favored because of its immediacy and the chance it offers for direct human interaction. Ref. [54] states that the platform enables students to actively learn and apply the language in real time. Moreover, it enables individuals to promptly receive feedback and benefit from the complexities of interpersonal communication. In the field of business English, effective communication is essential, requiring not only linguistic accuracy but also attention to tone, emphasis, and context. Communication is significant not only for the information it conveys, but also for the way it is expressed. Face-to-face learning dynamics improve the understanding of the “how” aspect, leading to a more comprehensive and contextualized approach to teaching language.

Figure 7.

Preferred mode of learning.

In the context of the sustainability of the course, this preference presents both a potential advantage and a moral obligation. The potential of in-person education is determined by the strong demand and perceived value it holds. Institutions can benefit from this demand by increasing enrollment, maintaining the relevance of their courses, and potentially enhancing the value of their offerings.

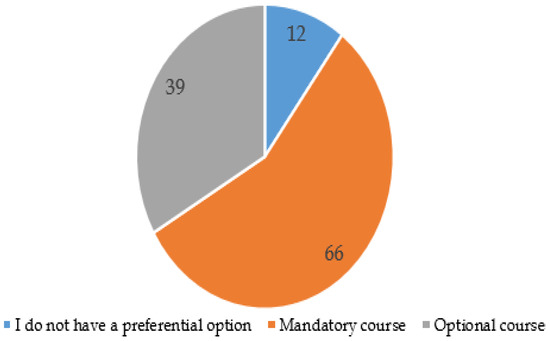

9.2. Optional or Mandatory

Figure 8 results shows that 66 out of 117 respondents favored making the course mandatory, while 39 preferred it to be optional. The increasing recognition of the importance and value of business English in today’s professional world is evident in the trend towards making the course compulsory. English has become the dominant language in the corporate world as a result of globalization and the increasing interdependence of the global economy [17]. Most participants likely do not view business English as a mere additional skill, but rather as a necessary requirement for career advancement and success.

Figure 8.

Optional or mandatory.

To cater to the demand of participants that want it to be optional or do not have any preference, we can argue for the importance of incorporating flexibility into course structures to enhance the sustainability of the course. Institutions may benefit from implementing a two-tiered approach. Advocating for the mandatory inclusion of foundational elements of business English in the curriculum ensures that all individuals acquire essential skills. Individuals interested in a more in-depth study of specialized aspects of business English may have the option to take elective advanced modules that provide a comprehensive examination [9].

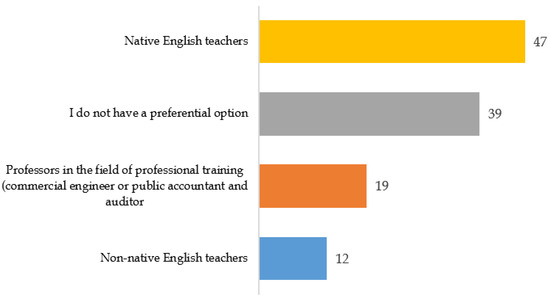

9.3. Teacher Preference

The linguistic background of the teaching faculty for a business English course was found to be a significant area of interest during the needs analysis. As illustrated in Figure 9, 47 of the participants preferred course delivery by native English speakers, while 39 did not have preference. The differing viewpoints presented here raise important questions and have significant implications for the long-term viability of a business English course.

Figure 9.

Teacher preference.

The preference for native English-speaking instructors is often based on the perceived effectiveness of the “native speaker model”. The preference for native speakers in language instruction is often associated with the belief that they have greater expertise in teaching abstract aspects of language, such as culture, pragmatics, and real-life contextual applications. According to [55], these elements are essential in business contexts. However, the significant lack of preference, which accounts for 39%, indicates a fundamental shift in the business English course industry. This group recognizes the importance of non-native teachers’ contributions. Ref. [55] found that non-native language instructors are more effective in teaching essential knowledge, specifically in the domains of grammar, writing, and reading.

The data presented here highlights the importance of developing a diverse faculty profile with a broad range of perspectives and expertise to enhance the long-term viability of courses. The inclusion of both native and non-native teachers in educational institutions allows for the utilization of the distinct advantages provided by each group. Native instructors enhance the authenticity of the learning experience by providing genuine linguistic encounters. On the other hand, instructors who are not native speakers can offer valuable contributions making effort to understand their students’ pedagogical and communicative needs [29]. This approach considers students’ preferences and effectively addresses the need for adaptability, relevance, and long-term sustainability of the course.

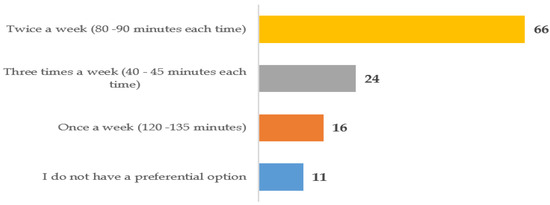

9.4. Preferred Number of Hours for Learning

A significant finding from the conducted target situation needs analysis of the business English course relates to preferences for the course’s frequency and duration. Figure 10 shows that the majority of respondents, specifically 66, preferred the course to be scheduled twice per week. Additionally, the participants expressed a preference for sessions lasting between 80 and 90 min. In contrast, 24 of respondents preferred a more frequent course format with shorter durations. The participants specifically requested that the course be held three times per week, with each session lasting approximately 40 to 45 min. The mentioned preferences, while seemingly based on convenience, have important implications for the sustainability of the business English course.

Figure 10.

Preferred number of hours for learning.

Most individuals tended to prefer longer and more extensive sessions, usually taking place twice a week and lasting between 80 and 90 min. This format has the potential to support in-depth exploration, extensive discourse, simulated scenarios, and practical analyses, which are all crucial components of an effective business English curriculum [17]. Extended sessions facilitate an immersive learning environment that promotes effective assimilation, practice, and reflection on the content, leading to improved retention and application.

It is crucial to acknowledge and address these preferences from a sustainability perspective. Offering flexible course structures or modular learning paths can effectively cater to the various learning styles of individuals. Institutions have the potential to implement a hybrid model that combines extended sessions for teaching fundamental content with shorter, voluntary sessions that focus on practical application [56]. The business English course’s adaptability makes it more appealing and relevant, meeting the needs of learners and improving its long-term sustainability.

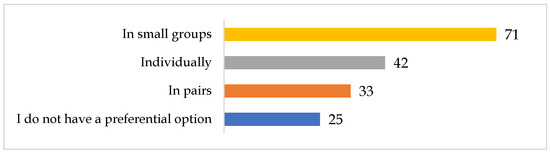

9.5. Preferred Ways to Learn

The preference for small group learning (71) is based on several important pedagogical insights (see Figure 11). Small groups in educational settings promote interactive and collaborative learning, facilitating peer discussions and collaborative problem solving [57]. The use of this instructional method can provide substantial benefits in the field of business English. Learners can enhance their understanding and practical application of language in authentic business contexts through activities such as role playing, business scenario simulations, and group discussions [58]. By employing realistic business scenarios, individuals can participate in simulated environments that promote the improvement and refinement of their language skills. This secure environment allows learners to adequately prepare for the diverse professional challenges they may face in real-life situations.

Figure 11.

Preferred ways to learn.

Integrating these learning preferences is highly significant in terms of course sustainability. The integration of small group activities and personalized learning experiences helps to cater to a diverse range of individuals, thereby increasing enrollment and retention rates in a course. By aligning the course structure with learners’ needs and desires, a business English course can efficiently facilitate language acquisition and establish itself as a flexible and receptive educational program. Adaptability is essential for maintaining the relevance and appeal of a course in an evolving educational landscape, thereby improving its long-term sustainability.

10. Research Implications

Pedagogical implications: Our research findings in terms of pedagogical implications indicate that the course effectively meets the communicative and pedagogical needs of our students. For instance, the participants advocate for the continuous prioritization of the four language skills (reading, listening, writing, and speaking) and the mandatory nature of the course. The majority of the learners expressed a preference for small group learning, native English teachers, and two longer sessions of classes, as opposed to individual learning, non-native English speakers, and three shorter sessions of classes. The students’ preference for small group learning has pedagogical implications for the sustainability of the course. This is consistent with the principles of active engagement [59], collaborative learning [60], and inclusivity [61]. Educators in our program should therefore employ discussion as a means to enhance students’ speaking skills [62] to improve their overall learning experiences. Additionally, the preference of students for native English-speaking instructors suggests a preference for instructors who possess advanced fluency and a wide range of vocabulary [63]. This underscores the importance of teachers in our program adapting their teaching styles, and institutions addressing potential biases and prioritizing inclusive hiring practices. Instructors, regardless of their native or non-native backgrounds, must possess effective cross-cultural communication skills in order to cultivate a multicultural learning environment. Lastly, ref. [64] found that students tend to prefer shorter sessions with longer hours, which can improve concentration and facilitate in-depth learning. This format allows for flexible scheduling [65]. Meeting the needs of our students in this regard will optimize learning outcomes.

Theoretical Implications: Previous research focused mainly on the key factors used to evaluate the sustainability of a course [18]. However, the integration of a target situation needs analysis in business English courses in this study holds substantial theoretical implications. The sustainability of the business English course is achieved by the alignment of the course with learner objectives, the cultivation of positive learning experiences, and the adaptation to evolving learners’ needs. The potential of this approach is grounded on its ability to evaluate their present situation, communicative, and pedagogical needs [8].

11. Conclusions

The aim of this study was to conduct a comprehensive needs analysis in order to create a sustainable business English course essential for designing, implementing and sustainability of the course. The results of the current situation analysis indicate that most participants reported having a low level of English proficiency. Therefore, this finding highlights the immediate need for comprehensive business English instruction. The communicative needs analysis emphasizes the importance of specific language skills, particularly in oral communication, auditory comprehension, and written comprehension. Given the ever-changing global business landscape, effective professional communication is becoming increasingly important. This includes the ability to communicate effectively in various contexts, such as meetings and interactions with international colleagues. Based on the pedagogical needs analysis, the results indicate a clear preference for in-person instruction, with the course being compulsory. There are differing opinions on the frequency and length of courses, as well as a preference for small group learning. Additionally, there is variation in instructor preferences. The analysis results demonstrate an intricate interaction of requirements. To ensure the long-term sustainability of a business English course, an integrated, responsive, and adaptive curriculum is essential. While the needs analysis offers valuable insights, it is crucial to recognize its inherent limitations. It is important to acknowledge that participants’ self-assessed proficiency levels in business English may not accurately reflect their actual level of competence. The use of self-reported data can introduce subjectivity and vulnerability to influence various individual factors. Additionally, it is worth considering that the participants in the study may not fully represent the broader population that requires business English courses. Future research could investigate participants’ actual proficiency levels using standardized assessments to obtain a more objective understanding of their language skills. It is important to examine the impact of blended learning methodologies, which combine traditional in-person teaching methods with digital platforms, to determine their effectiveness in enhancing proficiency in business English. Moreover, this study recognizes the possibility of methodological bias in data collection and analysis because of the sequential research design, where the quantitative phase comes before the qualitative phase. This sequence could impact participants’ responses and the interpretation of results, potentially introducing a bias towards the quantitative findings. Lastly, future research should investigate alternative sequential designs using mixed methods, evaluate the influence of the sequence on participant responses, and devise strategies to minimize potential bias.

Author Contributions

O.A.L.: Conceptualization, Investigation, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Writing—original draft. A.F.M.-P.: Methodology, Writing—review & editing. V.P.: Data curation, Visualization, Writing—review & editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The name of the IRB that granted approval is Ethics Committee of Universidad Catolica de Temuco, Chile, with approval number 122803/22.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. (Adapted from [32,34])

| Present situation analysis | Communication immediate needs (job and study) | Language skill development (preference) | |

| Stakeholders (participants) | Business English (teaching learning environment) | 22. How important is the ability to READ in English when studying the degree? | 30. The English course for undergraduate students should emphasize more the importance of: |

| 1. Age | 9. Do you consider the current amount (number of courses and hours) of English language instruction that is given to students of the program adequate to meet future professional needs about the language? | 23. The ability to READ in English is necessary to: | 31. Are you interested in studying business English? |

| 2. Course of study | 10. UFRO makes available enough audiovisual resources to learn business English (videos, audiobooks, digitized games, etc.) | 24. How often do you think you need to practice SPEAKING in English when studying for a degree? | 32. Why do you want to study business English? |

| 3. Gender | 11. UFRO makes available enough reading resources to learn business English (books, magazines, dictionaries, articles, etc.). | 25. How important is the ability to SPEAK English when studying the profession? | 33. How would you prefer to learn business English? |

| 4. Current year of study | 12. UFRO makes available sufficient resources for learning to write business English (books, guides, questionnaires, etc.). | 26. The ability to SPEAK ENGLISH is necessary to: | 34. With what methodology would you prefer to learn business English? |

| 6. Throughout your life, where have you studied English? | 13. UFRO makes available sufficient resources for learning oral business English communication (conversation sessions, specialized tutors, conversation videos, etc.). | 27. How often do you think you need to practice the ability to LISTEN in English when studying the major? | 35. I would like my teacher to use this material and/or teaching method: |

| 7. What is the level of English with which you entered your career at the University of La Frontera? (check only one option) | 28. How important is the ability to LISTEN English when studying the profession? | 36. For how long should the business English course be offered to the students of the major? | |

| 15. How do you perceive your level of English? | 29. The ability to LISTEN in English is necessary to: | ||

| 16. How would you rate your command of English in the following skills? Select a level for each skill. | 37. How often would you like to study the business English course? | ||

| 17. You have a problem in the following situations. Check the box that corresponds to your answer: YES or NO | 38. With whom do you prefer to learn business English? | ||

| 39. The business English course should be delivered as: | |||

| 40. The best way to teach the business English course would be: | |||

References

- Liu, W. A Study on the Integration of Business English Teaching and Intercultural Communication Skills Cultivation Model Based on Intelligent Algorithm. Secur. Commun. Netw. 2022, 2022, e2873802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jingzi, D.; Wenzhong, Z.; Dimond, E.E. The Integration of Intercultural Business Communication Training and Business English Teaching. Engl. Lang. Teach. 2016, 9, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Caraivan, L. Business English: A key employability skill? Quaestus 2016, 266, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Maican, M.-A. Challenges of teaching Business English in higher education. Bull. Transilv. Univ. Brasov. Ser. V Econ. Sci. 2017, 10, 273–280. [Google Scholar]

- Kurniawan, A.H.; Fitriani, N. Need Analysis For English For Special Purposes (Esp) In Informatics Management Class At Abc University. J. Pendidik. Dan Sastra Ingg. 2022, 2, 185–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paltridge, B.; Starfield, S. The Handbook of English for Specific Purposes; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013; Volume 592. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, J.C. Curriculum Development in Language Teaching; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- West, R. Needs analysis in language teaching. Lang. Teach. 1994, 27, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchinson, T.; Waters, A. English for Specific Purposes; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Strapasson, G. Needs Analysis and English for Business Purposes; Federal University of Technology: Curitiba, Brazil, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Fleiszer, A.R.; Semenic, S.E.; Ritchie, J.A.; Richer, M.; Denis, J. The sustainability of healthcare innovations: A concept analysis. J. Adv. Nurs. 2015, 71, 1484–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieff, S.J. Evolving Curriculum Design: A Novel Framework for Continuous, Timely, and Relevant Curriculum Adaptation in Faculty Development. Acad. Med. 2009, 84, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imai, M. Kaizen: The Key to Japan’s Competitive Success, 1st ed.; McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Gahungu, O.N. The Relationships among Strategy Use, Self-Efficacy, and Language Ability in Foreign Language Learners; Northern Arizona University: San Francisco, AZ, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammad, M.A.E.-M. A Proposed Content-Based Business English Program for Developing Students English Language Skills at the Faculty of Commerce. 2011. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/37502397/A_Proposed_Content_Based_Business_English_Program_for_Developing_Students_English_Language_Skills_at_Suez_Canal_Faculty_of_Commerce (accessed on 16 September 2023).

- Mirhadizadeh, N. Internal and external factors in language learning. Int. J. Mod. Lang. Teach. Learn. 2016, 1, 188–196. [Google Scholar]

- Dudley-Evans, T.; St John, M.J. Developments in English for Specific Purposes: A Multi-Disciplinary Approach; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Ferns, M.S.; Oliver, M.B.; Jones, M.S.; Kerr, M.R. Course sustainability = relevance + quality + financial viability. In Proceedings of the Evaluation and Assessment Conference: Assessment and Evaluation for Real World Learning, Brisbane, Australia, 29–30 November 2007; p. 37. [Google Scholar]

- Sustainably, L. The Australian Government’s National Action Plan for Education for Sustainability, Australian Government–Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts. Canberra. 2009. Available online: http://www.environment.gov.au/education/publications/pubs/national-action-plan.pdf (accessed on 30 November 2012).

- Hartman, P.; Newhouse, R.; Perry, V. Building a sustainable life science information literacy program using the train-the-trainer model. Issues Sci. Technol. Librariansh. 2015. Available online: https://aurora.auburn.edu/bitstream/handle/11200/48524/Life%20Science%20InfoLit.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 16 September 2023). [CrossRef]

- Elkhatat, A.M.; Al-Muhtaseb, S.A. Hybrid online-flipped learning pedagogy for teaching laboratory courses to mitigate the pandemic COVID-19 confinement and enable effective sustainable delivery: Investigation of attaining course learning outcome. SN Soc. Sci. 2021, 1, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peralta, L.R.; Marvell, C.L.; Cotton, W.G. A sustainable service-learning program embedded in PETE: Examining the short-term influence on preservice teacher outcomes. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 2020, 40, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ria, T.N.; Malik, D. A Need Analysis in English for Business Material at Economic Faculty of Pandanaran University. Edulingua J. Linguist. Terap. Dan Pendidik. Bhs. Ingg. 2020, 7, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y. An Empirical Study on Needs Analysis of College Business English Course. Int. Educ. Stud. 2012, 5, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zela, E. Need analysis in Business English: Course instructor perspective in identifying students’ needs. Eur. Acad. Res. 2017, V, 3014–3026. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z. Identities in needs analysis for Business English students. ESP Today 2013, 1, 26–44. [Google Scholar]

- Wello, M.B. Fundamental Aspects in Teaching Business English; Unpublished Paper; UNM: Makassar, Indonesia, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, C. Business English. Lang. Teach. 1993, 26, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, M.; Johnson, C. Teaching Business English; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Dawadi, S.; Shrestha, S.; Giri, R.A. Mixed-methods research: A discussion on its types, challenges, and criticisms. J. Pract. Stud. Educ. 2021, 2, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.R. Research governance and diversity: Quality standards for a multi-ethnic NHS. NT Res. 2003, 8, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayr, W.; Foo, T.C.V.; Mohamad, A. Target Situation Analysis in Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) in Malaysia-Based Multi-National Enterprises: The Case of German. Target 2015, 7, 94–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yulia, H.; Agustiani, M. An ESP needs analysis for management students: Indonesian context. Indones. Educ. Adm. Leadersh. J. 2019, 1, 35–44. [Google Scholar]

- Lasekan, O.A.; Salazar-Aguilar, P.; Botto-Beytía, A.M.; Boris, A.; Humanidades, N.D.C.S. Needs Analysis of Chilean Students of Dentistry for Dental English Course Development. World 2022, 12, 162–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chyung, S.Y.; Barkin, J.R.; Shamsy, J.A. Evidence-based survey design: The use of negatively worded items in surveys. Perform. Improv. 2018, 57, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, L.R.; Brown, G.T. Mixing interview and questionnaire methods: Practical problems in aligning data. Pract. Assess. Res. Eval. 2010, 15, 1. [Google Scholar]

- de Rezende, N.A.; de Medeiros, D.D. How rating scales influence responses’ reliability, extreme points, middle point and respondent’s preferences. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 138, 266–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyupa, S. A theoretical framework for back-translation as a quality assessment tool. New Voices Transl. Stud. 2011, 7, 35–46. [Google Scholar]

- Papachristou, N.; Vasileios, R.; Sarafis, P.; Bamidis, P. Translation, cultural adaptation and pilot testing of a questionnaire measuring the factors affecting the acceptance of telemedicine by Greek cancer patients. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0278758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simkus, J. Convenience Sampling: Definition, Method and Examples. 2022. Available online: https://www.simplypsychology.org/convenience-sampling.html (accessed on 6 October 2022).

- Dillman, D.A. Mail and Internet Surveys: The Tailored Design Method—2007 Update with New Internet, Visual, and Mixed-Mode Guide; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, L.D.; Allen, J. Exploring ethical issues associated with using online surveys in educational research. Educ. Res. Eval. 2015, 21, 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeSimone, J.A.; Harms, P.D.; DeSimone, A.J. Best practice recommendations for data screening. J. Organ. Behav. 2015, 36, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijer, R.R.; Niessen, A.S.M.; Tendeiro, J.N. A practical guide to check the consistency of item response patterns in clinical research through person-fit statistics: Examples and a computer program. Assessment 2016, 23, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maguire, M.; Delahunt, B. Doing a thematic analysis: A practical, step-by-step guide for learning and teaching scholars. All Irel. J. High. Educ. 2017, 9, 3351. [Google Scholar]

- Kong, Y. The role of experiential learning on students’ motivation and classroom engagement. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 771272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris Sr, D.E.; Scott, J. A Pilot Study Examining the Effects of Time Constraints on Student Performance in Accounting Classes. J. Instr. Pedagog. 2017, 18, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Ristić, I.; Runić Ristić, M.; Savić Tot, T.; Tot, V.; Bajac, M. The effects and effectiveness of an adaptive e-learning system on the learning process and performance of students. Int. J. Cogn. Res. Sci. Eng. Educ. IJCRSEE 2023, 11, 77–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Intaraprasert, C. Reading Strategies Employed by University Business English Majors with Different Levels of Reading Proficiency. Engl. Lang. Teach. 2014, 7, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, M.; Kitamura, S.; Shimada, N.; Utashiro, T.; Shigeta, K.; Yamaguchi, E.; Harrison, R.; Yamauchi, Y.; Nakahara, J. Development and evaluation of English listening study materials for business people who use mobile devices: A case study. Calico J. 2011, 29, 44–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerritsen, M.; Nickerson, C. BELF: Business English as a Lingua Franca; Edinburgh University Press: Edinburgh, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Vinke, A.A.; Jochems, W. English proficiency and academic success in international postgraduate education. High. Educ. 1993, 26, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, M.S. English Language Development: Preparing for a Business Career. e-J. Bus. Educ. Scholarsh. Teach. 2018, 12, 107–126. [Google Scholar]

- Gherheș, V.; Stoian, C.E.; Fărcașiu, M.A.; Stanici, M. E-learning vs. face-to-face learning: Analyzing students’ preferences and behaviors. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jieyin, L.; Gajaseni, C. A Study of Students’ Preferences towards Native and Non-Native English Teachers at Guangxi University of Finance and Economics, China. LEARN J. Lang. Educ. Acquis. Res. Netw. 2018, 11, 134–147. [Google Scholar]

- Trout, B. The effect of class session length on student performance, homework, and instructor evaluations in an introductory accounting course. J. Educ. Bus. 2018, 93, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosadi, F.S.; Nuraeni, C.; Priadi, A. The use of small group discussion strategy in teaching English speaking. Pujangga J. Bhs. Dan Sastra 2020, 6, 134–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandasari, B. Implementing Role Play in English for Business Class. Teknosastik 2017, 15, 60–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiely, F.; McCarthy, M. The effect of small group tutors on student engagement in the computer laboratory lecture. J. Scholarsh. Teach. Learn. 2019, 19, 141–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haugland, M.J.; Rosenberg, I.; Aasekjær, K. Collaborative learning in small groups in an online course—A case study. BMC Med. Educ. 2022, 22, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frykedal, K.F.; Chiriac, E.H. Student collaboration in group work: Inclusion as participation. Int. J. Disabil. Dev. Educ. 2018, 65, 183–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Ertmer, A. Examining the effect of small group discussions and question prompts on vicarious learning outcomes. J. Res. Technol. Educ. 2006, 39, 66–80. [Google Scholar]

- Ghane, M.H.; Razmi, M.H. Exploring the Effectiveness of Native and Non-Native English Teachers on EFL Learners’ Accuracy, Fluency, and Complexity in Speaking. Educ. Res. Int. 2023, 2023, 4011255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molloy, K.; Moore, D.R.; Sohoglu, E.; Amitay, S. Less is more: Latent learning is maximized by shorter training sessions in auditory perceptual learning. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e36929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warneke, K.; Wirth, K.; Keiner, M.; Lohmann, L.H.; Hillebrecht, M.; Brinkmann, A.; Wohlann, T.; Schiemann, S. Comparison of the effects of long-lasting static stretching and hypertrophy training on maximal strength, muscle thickness and flexibility in the plantar flexors. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2023, 123, 1773–1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).