Abstract

This research proposes a gamified approach to creating a culture for sustainable-oriented innovation. Specifically, we use action research to explore the mechanisms through which business decision-makers (such as entrepreneurs, executives and managers) reflect on their practices and obstacles to innovation, and then we use gamification to stimulate the involvement and creativity of managers. The main contribution of this paper is the design of a one-day gamified workshop in which participants collaborate first to identify common values and then to drive the co-creation of sustainable innovations. The workshop has been applied with managers of a real company to evaluate its playability and to validate its effectiveness in creating a culture for sustainable innovation.

1. Introduction

Firms are increasingly required to adopt sustainable development goals (SDGs) [1] as a guide to their business strategies. However, only few have already transformed their culture to favour values-based sustainable-oriented innovation (SOI) [2,3]. Previous studies agree that most organizations have not yet understood the long-term implications of their businesses, so they have to make considerable efforts to reframe their priorities, to mediate among the conflicting objectives of their numerous stakeholders and change their innovation practices [4,5].

The debate on how cultural and values-driven transformations can facilitate SOI is not yet well developed [6], and there is little understanding on the normative approaches that can be consistently integrated throughout this process. The lack of consolidated knowledge as well as of practical experiences prevent the diffusion of good practices [7,8], so far that it is claimed that SOI still relies on trial-and-error attempts [9].

To fill this gap, this paper aims at developing a gamified approach to create a culture for sustainable innovation. The work is part of IMPACT, a research project funded by the European Commission within the Erasmus+ Knowledge Alliance Program. The overall purpose of this project is to translate SDGs into everyday business, developing new ways to put decision-makers’ values into practice and illustrating how sustainability challenges can unlock innovation. It is in fact claimed that only few firms have already established practices that are grounded on their corporate culture and values to drive sustainability-oriented innovation [2]. Through a combination of action research (AR) and gamification, this paper presents a workshop to facilitate alignment of conflicting values among the company decision-makers to tackle the challenges of SOI. The rest of the paper is structured as follows: Section 2 presents a short background on both values-based SOI and gamification; Section 3 illustrates the research methodology; Section 4 presents the workshop structure while Section 5 discusses the results obtained from its application, according to the AR cycle. The last section draws some conclusions, limitations and research avenues.

2. Background

2.1. Values-Based Sustainable-Oriented Innovation

SOI is purposed to develop innovations through a new philosophical and cultural approach that considers the three aspects of sustainability, namely economic, social and environmental [10]. It is about rethinking the company’s purpose and culture to create shared value [11] through new, more sustainable products, processes and practices. This requires the adoption of more human-centred participatory methods such as design thinking and gamification [12]. In this case, the aim is to treat sustainability as a socio-technical challenge that requires mediation among complex and frequently divergent contextual factors, such as technologies, regulations, consumer behaviours and cultures [4]. It is said that firms need to embrace a broader perspective and adopt an ecosystem view that looks beyond their own boundaries [8,13]. Furthermore, firms should move from a stand-alone strategy, in which each business unit moves independently, to integrated strategies in which sustainability challenges are rooted in the corporate culture [14]. Finally, some studies show how achieving greater alignment of conflicting values can positively influence the process of SOI [2,15]. The mentioned literature defines values as a relatively stable and ordered system of priorities, which provides a decisive reference in people’s social lives. In other words, values are beliefs that relate to desirable goals that: (a) go beyond certain situations or events, (b) serve as standards and criteria, and (c) are ordered according to their relative importance [16]. This relative importance determines people’s behaviours and actions. It follows that values are persistent and should not be confused with interests. Interests in fact can be mediated in exchange for something, while values resist simple negotiation since they define ‘who we are’ [6].

2.2. Gamification

The term gamification was coined in 2002 and gained widespread interest in the following years [17,18,19]. Today, it refers to the introduction of game elements in non-game situations to encourage people’s motivation, enjoyment and engagement, particularly in work environments and situations of complex tasks and challenging objectives [20,21]. In fact, when faced with obstacles, people may feel depressed, overwhelmed, frustrated or cynical. These feelings are not present in a gaming environment, in which users are fully immersed in interesting tasks and fall often into a ‘state of flow’. This can be defined as ‘a feeling of happiness and inspiration associated with playing a game that prevents the user from getting bored’ [22]. Therefore, gamification tries to create a fun atmosphere that stimulates people’s openness, collaboration and cultural alignment [23]. In addition, it facilitates knowledge sharing, creative thinking, team spirit, consensus building and reduction of inhibition thresholds [24]. Gamification should neither be confused with reward systems nor with loyalty programs. These merely persuade people to perform actions in return for (a promise of) some earnings [25]. Conversely, gamification is much more than this, and the introduction of game elements, competition and rewards must be accurately conceived to comply case by case with what really motivates and keeps people. Gamification can be applied to any business domain [26,27]. However, it plays a key role in innovation tasks to promote creativity and out-of-the-box thinking [28]. Some studies also show how gamification can contribute to simplifying the complexity of decision-making since it favours a common understanding of the problem to be addressed [25]. Breuer and Ivanov [29] suggest that gamification can be proficiently used in SOI. These authors in particular claim that: (a) dilemma games can increase vertical and horizontal communication as well as awareness and understanding of a firm’s values; (b) gamified workshops can enable the creation of values-oriented frameworks that thus guide collaboration and idea generation; and (c) gamification can also be used for open innovation to promote collaboration among different departments of the same firm or different firms of the same value chain.

In light of the above considerations, the research questions (RQs) that this study wants to address can be explicated as follows:

- RQ1: How can the culture for SOI be created and fostered?

- RQ2: How can gamification be used to develop SOI?

The following section describes the research methodology that addresses these RQs.

3. Research Methodology

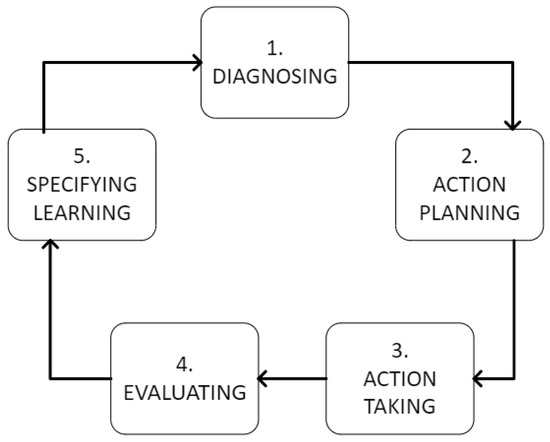

This paper takes place within the context of the IMPACT research project, which unites innovation scholars and practitioners to improve the teaching and coaching of SOI. This project involves a number of different academic and industrial partners such as 3M (Madrid, Spain), Baker Hughes (Florence, Italy), TÜV Nord (Hannover, Germany), South Poland Cleantech Cluster (Crakow, Poland), University of Florence (Florence, Italy), School of Business of Leipzig (Leipzig, Germany), Universidad Complutense de Madrid (Madrid, Spain), Hochschule für Medien, Kommunikation und Wirtschaft of Berlin (Berlin, Germany) and Cracow University of Technology (Crakow, Poland). The methodology adopted by the IMPACT project is a mix of literature review, ethnography and action research (hereafter AR). In particular, this paper adopts AR as a participatory and democratic methodology that combines theory and practice and action and reflection to find practical solutions to important issues such as the prosperity of people and communities [30]. In AR, the intervention allows the insights coming from what the managers accomplish, instead of what they say they are accomplishing, as in case-based research [31]. With AR, researchers and system users collaborate to achieve some common goals. As such, they develop practical knowledge around a given phenomenon [32]. In this sense, AR requires deep explorations of situations and contexts, which is usually achieved by interviewing people. Furthermore, this methodology was integrated with an ethnographic approach, whereby we not only interviewed the managers but also observed their work context and daily practices in an ethnographic mode of inquiry [33]. Based on the interviews and our direct observations, we assigned the selected managers for the gamified workshop, as the role aligned consistently with their daily work activities. It is claimed that the AR method is excellent for introducing innovative practices into systems that tend to inhibit changes and innovations [34,35]. For this reason, we have combined AR and gamification to investigate how the barriers to SOI can be overcome. Basically, AR implies that researchers and practitioners are involved together in a cycle of activities that can also iterate in a continuous flow [31]. This process moves from diagnosis to intervention and reflective learning and constitutes the key element of this methodology [31]. More in detail, this cycle is composed of five phases (see Figure 1). In the first phase (DIAGNOSIS), the researchers analyse the situation to identify and define the problem setting. In the second phase (ACTION PLANNING), a detailed plan of action to deal with the problem is elaborated. The planned actions are then implemented in the third phase (ACTION TAKING), while in the fourth phase (EVALUATION), the researchers collect feedback and evaluate the outcomes from their implementations. Through critical reflection, the final phase (SPECYFING LEARNING) is focused to elaborate and share the lessons learned inside and outside the problem context.

Figure 1.

The phases of AR.

According to the mentioned cycle, Section 4 describes the findings of this work.

4. Findings from the Application of the AR Cycle

4.1. Diagnosing

Researchers interviewed eight managers of one large industrial firm that was partner of the research project, with the aim to understand the barriers to values-based SOI. One workshop was also conducted in which researchers and managers analysed data from these interviews, in order to agree on cultural issues of SOI. Combining these data with the literature on values-driven SOI [2], we found the following barriers:

- B1. Lack of a culture of sustainability and innovation. Specialization, silo-oriented mindset and functional culture represent a significant barrier to SOI; for example, the engineering mindset is relatively resistant to the integration of sustainability aspects in feasibility analysis; therefore, it hinders the necessary cross-functional collaboration.

- B2. Lack of communication regarding sustainability issues that involves all levels of the organization. Without communication, alignment between the values of the organization and those of employees is more difficult; misalignment requires greater efforts to engage all the stakeholders in the SOI processes.

- B3. Lack of a holistic approach. Organisations that want to develop SOI have to consider and embrace the broader system of which they are a part, rather than dealing with only those subsystems over which they have full control.

- B4. Resistance to change. SOI requires fundamental changes to business practices such as customers engagement and revenue generation mechanisms.

- B5. Lack of collaboration. There may be problems with different priorities, divergent interests and concerns of functional teams.

4.2. Action Planning

We elaborate a plan with clear objectives based on the identified barriers:

- Identify the best practices and shared values to nurture SOI culture.

- Design a gamified workshop to facilitate values-based SOI.

4.3. Action Taking and Evaluating

Following the action plan, we designed, implemented and evaluated a gamified workshop for SOI. The workshop is conceived to allow participants to first listen and understand each other, their values, practices and concerns related to sustainability. Then, there is room for sharing good practices, behaviours and initiatives. In the evaluation phase, people reflect on both their own values and those of their organization and identify what values can facilitate SOI. Then, participants are required to generate ideas for improving the sustainability of products, services and processes. They also look for solutions to create shared value for the ecosystem in which the company operate. Last, they jointly evaluate the pros and cons of their proposals.

4.4. Action Taking and Evaluating

In this phase, the researchers analyse the results of previous activities, identify the lesson to be learned and share them with the academic and industrial communities. These lessons refer, on the one hand, to solutions and ideas for stimulating a broader culture of sustainability and, on the other, to the practices for facilitating values-driven SOI.

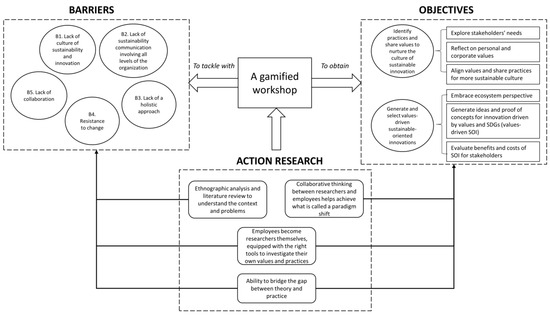

The framework in Figure 2, which is the first contribution of this research, summarises the contents of the AR cycle, connects the barriers to the objectives of the action plan and ultimately justifies the choice of AR to foster SOI through a gamified workshop.

Figure 2.

AR framework for SOI.

5. Designing a Gamified Workshop for Values-Driven SOI

We decided to design an in-presence workshop. In-presence has been preferred, on the one hand, to obtain detoxification from the abundance of virtual meetings and, on the other, to favour socialisation and encourage physical interaction of participants. Conducting the workshops in person was considered also beneficial for facilitators, so they can read non-verbal communication, feel emotions, grasp what is working and not working and act accordingly [36]. In designing the workshop, the authors worked on two mutually complementing tracks: choosing which gamification techniques could help more in tackling the SOI barriers [12] and including mechanisms for motivating and engaging participants. Since game elements per se do not automatically create better engagement, we used the Octalysis framework [37], which is acknowledged as the most comprehensive method to introduce gamification in work contexts [38]. Here, the assumption is that people are not motivated, and consequently they do not change their behaviours in the absence of some key drivers (cores) [39]. In the following sections, we explain these choices in more detail.

5.1. Games Selection and Application of the Octalysis Framework

As said, we intersected the literature on gamification [40] and sustainable innovation [41] to evaluate which games could facilitate tackling SOI barriers. We also modified the original version of the selected games to fit with the specific purpose and contextual constraints. Table 1 shows the selected games and connects them to the SOI barriers illustrated in Section 4.1. Then, Table 2 describes the application of the Octalysis framework and explains which cores have been applied to the workshop and why they are relevant.

Table 1.

Linkages between games and barriers.

Table 2.

The Octalysis framework adapted from [37].

5.2. The Workshop Structure

The main contribution of this paper is the design of a workshop that facilitates values-based SOI. Participants can be managers of different departments of the same firm, as well as from different firms of the same value chain. The overall objective of the workshop is to create a gamified environment to stimulate collaboration, co-creation and idea generation for values-driven SOI. In this regard, participants are asked to read some documents (things to know) that illustrate the basic concepts of SOI. Knowledge about the firm’s values can also be subject to evaluation prior to attending the workshop, and eventual gaps should be filled through information and preliminary discussion. The workshop is structured into four levels, as described in Table 3. At the end of the workshop, participants provide feedback through a questionnaire, which investigates agreement and understanding about the following trajectories (i.e., from values to innovation), as well as the engagement mechanisms. The researchers then elaborate and share with the participants a report containing the lessons learned in the form of take-aways. In detail, through the handout analysis, the researchers identify the good practices that the firm has already implemented or could easily implement to promote SOI. Then, the report is complemented by including the shared values that can drive SOI, as far as they emerge from the interactions among the workshop participants. Researchers also collect and evaluate the ideas proposed by the participants. The most promising ideas are supplemented by the list of opposing forces (as discussed in the last workshop activity) to help managers in assessing their feasibility.

Table 3.

Workshop structure.

5.3. Validating the Workshop

In the activities initially carried out (level 1), the workshop participants discussed and identified the values that primarily guide the work of their respective teams, and then shared them with the participants from the other team. For example, in the simulation, one team suggested collaboration, sustainability and dissemination of knowledge as key values while the other team suggested concreteness, awareness and encouragement. Significant mismatches and misalignments were found with respect to the values indicated as priorities and those that the company included as the guiding values of its identity and legitimacy. For example, it emerged among the company’s primary guiding values, the productivity of the individual rather than the team/business function of which the individual is a part, incentivizing competition and conflict rather than alliances and collaboration.

Thus, in the second level, among the shared values, some were identified from both groups that appeared more related to the goals of sustainable innovation. Specifically, collaboration among different actors (introducing the concepts of collaborative network and alliance), communication, reciprocity (using more co-working spaces), inclusiveness, openness to others, etc.

In the third level, a series of proposals and ideas came out to be evaluated against the value map to increase sustainability. For example, in the simulated workshop, in light of the common values and ideas that emerged in the previous stage, actions were proposed to spread a collaboration-oriented mindset such as using co-working and open spaces, introduction in the corporate vocabulary (in emails, sites or official speeches by HR or top managers) of “keywords” such as “network” or “partnership” that spread a collaborative spirit in the company starting from the top and the introduction of mechanisms for staff evaluation not (or at least not only) of the individual but of the team/function of which he/she is part.

Thus, in the last level, the forces for and against the implementation of the above ideas/initiatives were highlighted. For example, while there is growing sentiment among individuals about the need to innovate to carry out business activity and change decision-making processes, there is still a lack of incentives such as KPIs for evaluating one’s performance and decision-making in terms of sustainable productivity.

Regarding the second goal of the AR process, i.e., the co-creation of sustainable innovations, an interesting result is the innovation that was chosen and then evaluated by the participants during the last level. The main idea has been stated as: ‘Incubate only ideas that take sustainability into consideration’.

This innovation can be classified as system change because it has a focus on people and their values. Finally, it is a solution that looks beyond its functional area by prompting new entrepreneurs to consider sustainability in their business. Definitely, an ambitious innovation involving both groups is represented. In addition, the enabling forces and barriers identified in the last level for this innovation are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Identified forces.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

The previous literature agrees that sustainability-oriented innovation (SOI) originates from radical changes to the corporate culture [2,3]. Unfortunately, there are a lack of models to guide and facilitate these transformations [6]. To fill this gap, this paper addresses two research questions, namely (RQ1) ‘How can the culture for SOI be created and fostered?’ and (RQ2) ‘How can gamification be used to develop SOI?’ The paper presents a novel approach that combines concepts from gamification and the SOI literature. We adopt the Octalysis Framework to facilitate the unveiling, discussion and alignment of values and cultural aspects pertaining to SOI. More specifically, we respond to RQ1 by showing how a structured in-person workshop in which company managers and decision-makers can participate and interact under the guidance of sustainability experts who act as workshop facilitators, can enable communication, collaboration and idea generation (co-creation). In line with previous studies [19,20,25], we exploit the energy and creativity generated during the workshop to address the barriers to SOI, e.g. reticence to change and innovation (B4), openness to a well-rounded and holistic view rather than closed and restricted to one’s own work activities (B3), lack of communication (B2), collaboration (B5) and the spread of a culture under the banner of sustainability (B1). We also respond to RQ2 showing how the fun atmosphere of gamification can be used to create engagement and motivation. To this regard, we adapt the human-centred Octalysis framework [37] which has been identified among the best frameworks to introduce gamification in business contexts [38]. Specifically, we identify the five cores that are key for SOI and show how they can be used in the workshop (see Table 3).

Therefore, contributions from this research are twofold. From one side, we connect gamification and SOI and show opportunities for future theoretical intersections. On the other, we present the structure of a workshop that can be applied by innovation and sustainability managers, as well as by facilitators, to tackle the barriers to SOI.

This research comes also with some limitations. For instance, the AR has involved only a large industrial firm, which is a partner of the funded research project IMPACT. Validation of the workshop outcomes should therefore concern a larger sample of firms of different sizes and operating in different sectors. Future research should also address how values-driven SOI can become everyday practices at any company level.

In particular, the main limitation concerns the validation of the framework, which is limited to only one case, namely a large, global manufacturer that was among the partners of our IMPACT project. Future research could be aimed at generalising the contribution of this research (i.e., the design of the gamified workshop for SOI) through the application of the workshop in a larger sample of companies from different sectors and of different sizes.

Author Contributions

Formal analysis, F.B.; Writing–original draft, M.S.; Writing–review & editing, M.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This publication has been partially funded with support from the European Commission as part of the Erasmus+ Program IMPACT. It reflects the views only of the authors, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to the Foundation for Research and Innovation of the University of Florence, which contributed significantly to the development of this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Schroeder, P.; Anggraeni, K.; Weber, U. The relevance of circular economy practices to the sustainable development goals. J. Ind. Ecol. 2019, 23, 77–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breuer, H.; Ivanov, K.; Abril, C.; Dijk, S.; Monti, A.; Rapaccini, M.; Kasz, J. Building values-based innovation cultures for sustainable business impact. In Proceedings of the 2021 Conference of the International Society for Professional Innovation Management (ISPIM), Berlin, Germany, 20–23 June 2021; pp. 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Khurana, S.; Luthra, S.; Haleem, A.; Kumar, A.; Mannan, B. Can sustainability be achieved through sustainable oriented innovation practices? Empirical evidence of micro, small and medium scale manufacturing enterprises. Sustain. Dev. 2022, 30, 1591–1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, E. Managing for Stakeholders: Trade-offs or Value Creation. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 96, 7–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Sánchez, I.M.; Amor-Esteban, V.; Aibar-Guzmán, C.; Aibar-Guzmán, B. Translating the 2030 Agenda into reality through stakeholder engagement. Sustain. Dev. 2022, 31, 941–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breuer, H.; Lüdeke-Freund, F. Values-Based Innovation Management. Innovating by What We Care About; Palgrave Macmillan: Hampshire, UK, 2017; ISBN 978-1137516619. [Google Scholar]

- Rupeika-Apoga, R.; Petrovska, K. Barriers to Sustainable Digital Transformation in Micro-, Small-, and Medium-Sized Enterprises. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majid, S.; Zhang, X.; Khaskheli, M.B.; Hong, F.; King, P.J.H.; Shamsi, I.H. Eco-Efficiency, Environmental and Sustainable Innovation in Recycling Energy and Their Effect on Business Performance: Evidence from European SMEs. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brones, F.; Zancul, E.; Carvalho, M.M. Insider action research towards companywide sustainable product innovation: Ecodesign transition framework. Int. J. Manag. Proj. Bus. 2020, 14, 150–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, R.; Jeanrenaud, S.; Bessant, J.; Denyer, D.; Overy, P. Sustainability-oriented innovation: A systematic review. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2016, 18, 180–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; Hills, G.; Pfitzer, M.; Patscheke, S.; Hawkins, E. Measuring Shared Value: How to Unlock Value by Linking Social and Business Results. 2012. Available online: https://www.sharedvalue.org/resource/measuring-shared-value (accessed on 3 May 2023).

- Breuer, H.; Lüdeke-Freund, F. Values-based stakeholder management: Concepts and methods. In Rethinking Strategic Management: Sustainable Strategizing for Positive Impact; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 217–239. ISBN 9783030060145. [Google Scholar]

- Oskam, I.; Bossink, B.; de Man, A.P. Valuing value in innovation ecosystems: How cross-sector actors overcome tensions in collaborative sustainable business model development. Bus. Soc. 2020, 60, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guldmann, E.; Huulgaard, R.D. Barriers to circular business model innovation: A multiple-case study. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 243, 118160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Midgley, G.; Reynolds, M. Systems/operational research and sustainable development: Towards a new agenda. Sustain. Dev. 2004, 12, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H. An overview of the Schwartz theory of basic values. Online Read. Psychol. Cult. 2012, 2, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landers, R.N.; Auer, E.M.; Collmus, A.B.; Armstrong, M.B. Gamification science, its history and future: Definitions and a research agenda. Simul. Gaming 2018, 49, 315–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dicheva, D.; Dichev, C.; Agre, G.; Angelova, G. Gamification in education: A systematic mapping study. Educ. Technol. Soc. 2015, 18, 75–88. [Google Scholar]

- Seaborn, K.; Fels, D.I. Gamification in theory and action: A survey. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 2015, 74, 14–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deterding, S.; Dixon, D.; Khaled, R.; Nacke, L. From game design elements to gamefulness: Defining “gamification”. In Proceedings of the 15th International Academic Mindtrek Conference: Envisioning Future Media Environments (MindTrek), Tampere, Finland, 28–30 September 2011; pp. 9–15. [Google Scholar]

- Ouariachi, T.; Li, C.Y.; Elving, W.J. Gamification approaches for education and engagement on pro-environmental behaviors: Searching for best practices. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patricio, R.; Moreira, A.C.; Zurlo, F. Gamification in innovation teams. Int. J. Innov. Stud. 2022, 6, 156–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bicen, H.; Kocakoyun, S. Perceptions of managers for gamification approach: Kahoot as a case study. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Learn. 2018, 13, 72–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silic, M.; Back, A. Impact of Gamification on User’s Knowledge-Sharing Practices: Relationships between Work Motivation, Performance Expectancy and Work Engagement. In Proceedings of the 50th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS), Hilton Waikoloa Village, HI, USA, 4–7 January 2017; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Patricio, R.; Moreira, A.C.; Zurlo, F. Gamification approaches to the early stage of innovation. Creat. Innov. Manag. 2018, 27, 499–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultan, Y.H.; Suhail, K.S. The impact of significant factors of digital leadership on gamification marketing strategy. Int. J. Adv. Res. Dev. 2019, 4, 29–33. [Google Scholar]

- Woźniak, J. Gamification for sales incentives. Contemp. Econ. 2020, 14, 144–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.H.Y.; Soman, D. Gamification of education. Rep. Ser. Behav. Econ. Action 2013, 29, 37. [Google Scholar]

- Breuer, H.; Ivanov, K. Gamification to address cultural challenges and to facilitate values-based innovation. In Proceedings of the 2020 Conference of the International Society for Professional Innovation Management (ISPIM), Virtual, 7–10 June 2020; pp. 1–15, ISBN 9789523354661. [Google Scholar]

- Brydon-Miller, M.; Greenwood, D.; Maguire, P. Why action research? Action Res. 2003, 1, 9–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avison, D.E.; Lau, F.; Myers, M.D.; Nielsen, P.A. Action research. Commun. ACM 1999, 42, 94–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Aken, J.E. Management research as a design science: Articulating the research products of mode 2 knowledge production in management. Br. J. Manag. 2005, 16, 19–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Øien, T.B. Methodological considerations in collaborative processes: A case of ethnographic action research. Int. J. Manag. Proj. Bus. 2023, 16, 165–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, R.S. Innovation action research: Creating new management theory and practice. J. Manag. Account. Res. 1998, 10, 89. [Google Scholar]

- Somekh, B. Action Research: A Methodology for Change and Development; Open University Press: Berkshire, UK, 2005; ISBN 9780335216581. [Google Scholar]

- Becerra, Z.M.; Fereydooni, N.; Kun, A.L.; McKerral, A.; Riener, A.; Schartmüller, C.; Walker, B.N.; Wintersberger, P. Interactive workshops in a pandemic: The real benefits of virtual spaces. IEEE Pervasive Comput. 2021, 20, 35–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, Y. Actionable Gamification: Beyond Points, Badges, and Leaderboards; Octalysis Media: Milpitas, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Tondello, G.F.; Kappen, D.L.; Ganaba, M.; Nacke, L.E. Gameful Design Heuristics: A Gamification Inspection Tool. In Human-Computer Interaction. Perspectives on Design (HCII 2019); Kurosu, M., Ed.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; Volume 11566, ISBN 9783030226466. [Google Scholar]

- Araújo, I.; Carvalho, A.A. Enablers and Difficulties in the Implementation of Gamification: A Case Study with Teachers. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, D.; Brown, S.; Macanufo, J. Gamestorming: A Playbook for Innovators, Rulebreakers, and Changemakers; O’Reilly Media, Inc.: Sebastopol, CA, USA, 2010; ISBN 978-0596804176. [Google Scholar]

- Bocken, N.; Short, S.; Rana, P.; Evans, S. A value mapping tool for sustainable business modelling. Corp. Gov. 2013, 13, 482–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bono, E. Six Thinking Hats: The Multi-Million Bestselling Guide to Running Better Meetings and Making Faster Decisions; Penguin Life: London, UK, 2016; ISBN 9780241257531. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).