The Rise of Collaborative Consumption in EU Member States: Exploring the Impact of Collaborative Economy Platforms on Consumer Behavior and Sustainable Consumption

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Literature Review

1.2. Problem Statement

- Examine how the collaborative economy is understood and applied in practice in EU member states;

- Analyze the main sectors of the collaborative economy and online platforms concerning European consumers’ consumption patterns;

- Identify the key aspects of the collaborative economy paradigm used to create the consumption model and purchasing behavior patterns.

2. Methods and Materials

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Sample

2.3. Statistical Processing

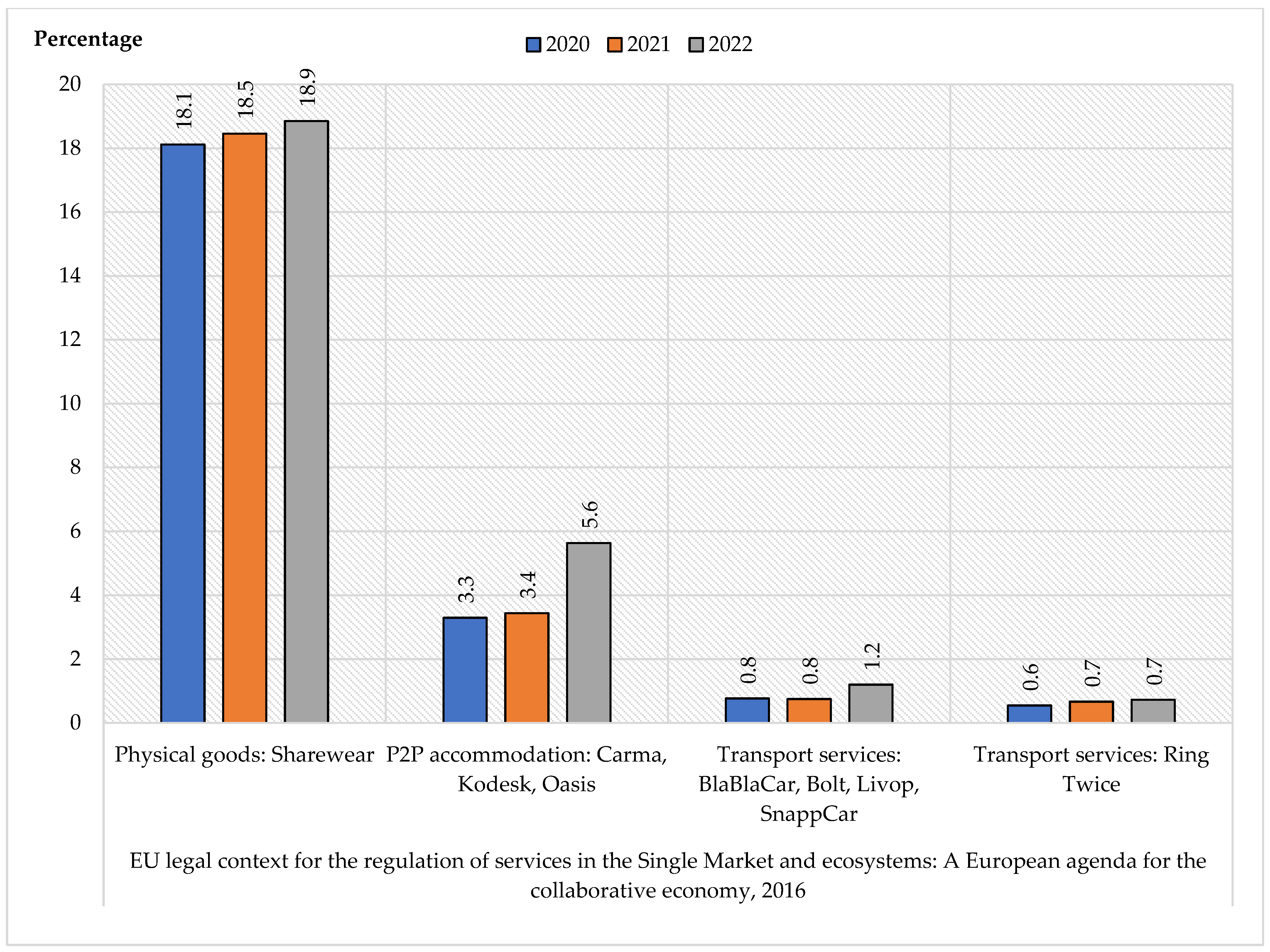

- The data are transformed to reflect the definition of the main sectors of the collaborative economy;

- An analytical method is used to collect data on the activities of online collaborative economy platforms and correlate them with the main sectors;

- The European consumer market, which includes the trade in goods and services through major online collaborative economy platforms, is visualized in terms of the main sectors using graphical data processing in Excel.

2.4. Ethical Issues

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

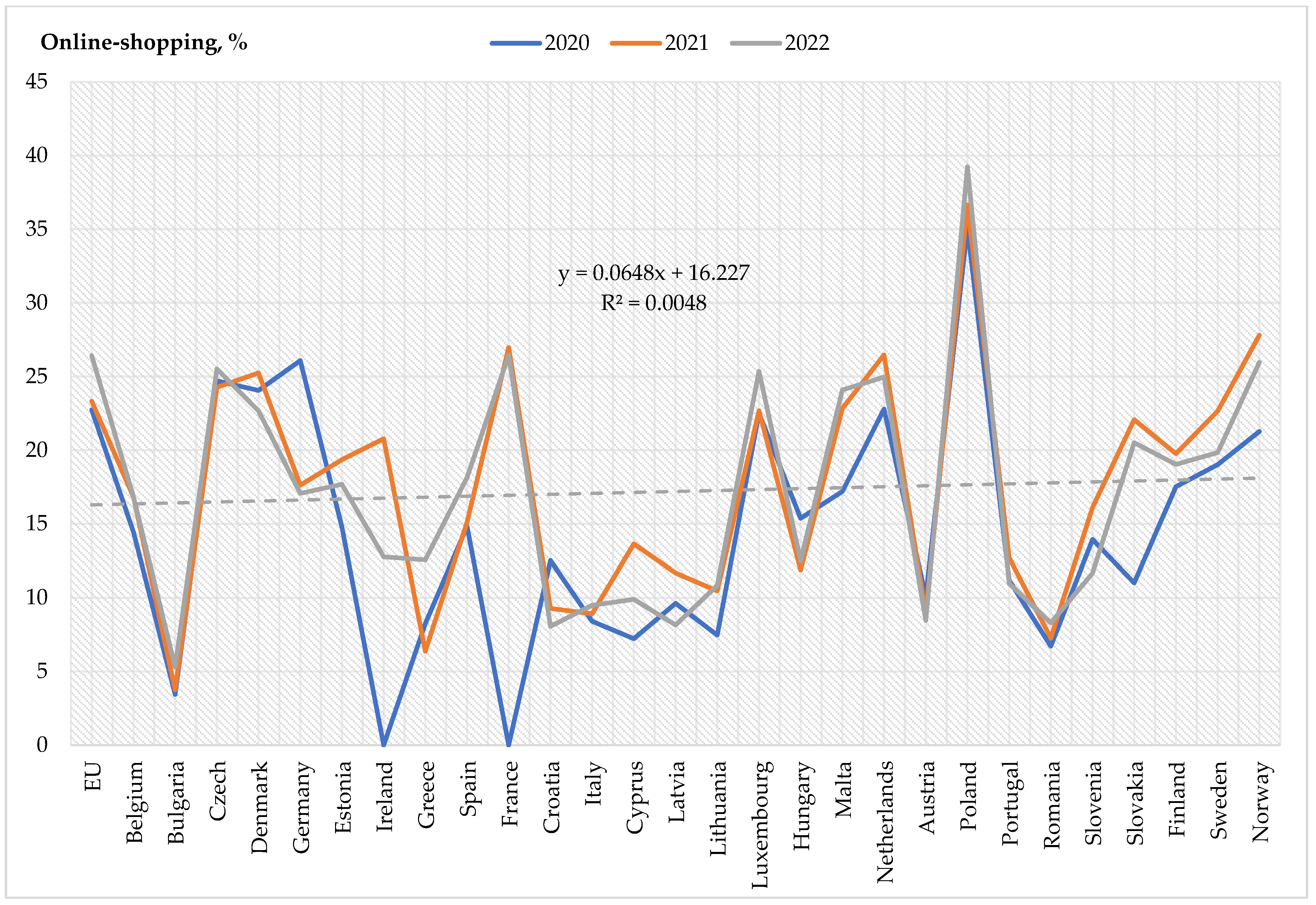

| Internet Purchases—Collaborative Economy (2020 Onwards) | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 |

|---|---|---|---|

| EU | 22.7 | 23.3 | 26.4 |

| Belgium | 14.4 | 16.8 | 16.8 |

| Bulgaria | 3.5 | 3.8 | 5.3 |

| Czech | 24.7 | 24.3 | 25.5 |

| Denmark | 24.1 | 25.2 | 22.7 |

| Germany | 26.1 | 17.6 | 17.1 |

| Estonia | 14.8 | 19.4 | 17.7 |

| Ireland | 0.0 | 20.8 | 12.8 |

| Greece | 8.3 | 6.4 | 12.6 |

| Spain | 14.8 | 15.1 | 18.2 |

| France | 0.0 | 27.0 | 26.4 |

| Croatia | 12.5 | 9.3 | 8.1 |

| Italy | 8.4 | 8.9 | 9.5 |

| Cyprus | 7.2 | 13.7 | 9.9 |

| Latvia | 9.6 | 11.7 | 8.2 |

| Lithuania | 7.5 | 10.5 | 10.8 |

| Luxembourg | 22.5 | 22.7 | 25.4 |

| Hungary | 15.4 | 11.9 | 12.5 |

| Malta | 17.2 | 22.8 | 24.1 |

| Netherlands | 22.8 | 26.5 | 25.0 |

| Austria | 10.1 | 9.0 | 8.5 |

| Poland | 35.1 | 36.7 | 39.2 |

| Portugal | 11.2 | 12.7 | 11.0 |

| Romania | 6.7 | 7.3 | 8.3 |

| Slovenia | 13.9 | 16.1 | 11.7 |

| Slovakia | 11.0 | 22.1 | 20.5 |

| Finland | 17.5 | 19.8 | 19.0 |

| Sweden | 19.0 | 22.7 | 19.8 |

| Norway | 21.3 | 27.8 | 26.0 |

References

- Statista. Digital & Trends. Consumer Trends 2023: Sustainability Edition. Report. Statista. Available online: https://www.statista.com/study/125082/consumer-trends-2023-sustainability-edition/ (accessed on 28 September 2023).

- World Economic Forum. Global Risks Report 2023, 18th Edition. Available online: https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Global_Risks_Report_2023.pdf (accessed on 28 September 2023).

- Guillén, M.F. 2030: How Today’s Biggest Trends Will Collide and Reshape the Future of Everything; St. Martin’s Press: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Statista. Industries/Economy & Politics. Overview. Statista. Available online: https://www.statista.com/markets/2535/topic/970/economy/#overview (accessed on 28 September 2023).

- Baruffati, A. Sharing Economy Statistics 2023 Trends. GITNUX. Available online: https://blog.gitnux.com/sharing-economy-statistics/ (accessed on 28 September 2023).

- Echikson, W. Europe’s Collaborative Economy Charting a Constructive Path Forward. Report. Brussels: Centre for European Policy Studies. Available online: http://aei.pitt.edu/103328/1/TFR-Collaborative-Economy.pdf (accessed on 28 September 2023).

- Cesnuityte, V.; Simonovits, V.; Klimczuk, A.; Balázs, V.; Miguel, C.; Avram, G. The state and critical assessment of the sharing economy in Europe. In The Sharing Economy in Europe: Developments, Practices, and Contradictions; Cesnuityte, V., Ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Germany, 2022; pp. 387–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatzopoulos, V.; Roma, S. Caring for sharing? The collaborative economy under EU law. Common Mark. Law Rev. 2017, 54, 81–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Waal, M.; Arets, M. From a sharing economy to a platform economy: Public values in shared mobility and gig work in the Netherlands. In The Sharing Economy in Europe: Developments, Practices, and Contradictions; Cesnuityte, V., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Germany, 2022; pp. 241–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertz, M.; Durif, F.; Lecompte, A.; Boivin, C. Does “sharing” mean “socially responsible consuming”? Exploration of the relationship between collaborative consumption and socially responsible consumption. J. Consum. Mark. 2018, 35, 392–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luna, I.; Fitó-Bertran, À.; Lladós-Masllorens, J.; Liébana-Cabanillas, F. Sharing Economy and the Impact of Collaborative Consumption; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Miguel, C.; Martos-Carrión, E.; Santa, M. A conceptualisation of the sharing economy: Towards theoretical meaningfulness. In The Sharing Economy in Europe: Developments, Practices, and Contradictions; Cesnuityte, V., Ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Germany, 2022; pp. 21–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyimóthy, S. Business models of the collaborative economy. In Collaborative Economy and Tourism: Perspectives, Politics, Policies and Prospects; Dredge, D., Gyimóthy, S., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Germany, 2017; pp. 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benoit, S.; Baker, T.L.; Bolton, R.N.; Gruber, T.; Kandampully, J. A triadic framework for collaborative consumption (CC): Motives, activities and resources & capabilities of actors. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 79, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabbous, A.; Tarhini, A. Assessing the impact of knowledge and perceived economic benefits on sustainable consumption through the sharing economy: A sociotechnical approach. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2019, 149, 119775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. The Collaborative Economy. Single Market. European Commission. Available online: https://single-market-economy.ec.europa.eu/single-market/services/collaborative-economy_en (accessed on 28 September 2023).

- Kuhzady, S.; Seyfi, S.; Béal, L. Peer-to-peer (P2P) accommodation in the sharing economy: A review. Curr. Issues Tour. 2022, 25, 3115–3130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista. Revenue of Platform Providers in the Sharing Economy Worldwide in 2017 and 2022. Statista Research Department. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/878844/global-sharing-economy-revenue-platform-providers/ (accessed on 28 September 2023).

- Lukasiewicz, A.; Sanna, V.S.; Diogo, V.L.A.P.; Bernát, A. Shared mobility: A reflection on sharing economy initiatives in European transportation sectors. In The Sharing Economy in Europe: Developments, Practices, and Contradictions; Cesnuityte, V., Ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Germany, 2022; pp. 89–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista. Market Capitalisation of Airbnb Worldwide from 2020 to 2023. Travel, Tourism & Hospitality/Accommodation. Statista Research Department. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/339845/company-value-and-equity-funding-of-airbnb/ (accessed on 28 September 2023).

- Pesonen, J.; Tussyadiah, I. Peer-to-peer accommodation: Drivers and user profiles. In Collaborative Economy and Tourism. Perspectives, Politics, Policies and Prospects; Dredge, D., Gyimóthy, S., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Germany, 2017; pp. 285–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossmannek, O.; Chen, M. Why people use the sharing economy: A meta-analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 387, 135824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, J. Sustainable Consumption Will Stimulate SUSTAINABLE products. Mastercard. Available online: https://www.mastercard.com/news/perspectives/2023/sustainable-consumption-will-stimulate-sustainable-production/ (accessed on 28 September 2023).

- Statista. Global Megatrends-Statistics & Facts. Society. Statista. Available online: https://www.statista.com/topics/3512/global-megatrends/#topicOverview (accessed on 28 September 2023).

- ESPON. Sharing-Stocktaking and Assessment of Typologies of Urban Circular Collaborative Economy Initiatives. Available online: https://www.espon.eu/sharing (accessed on 28 September 2023).

- European Union. Sustainable Development in the European Union Monitoring Report on Progress towards the SDGs in an EU Context 2023 Edition. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/15234730/16817772/KS-04-23-184-EN-N.pdf/845a1782-998d-a767-b097-f22ebe93d422?version=1.0&t=1684844648985 (accessed on 28 September 2023).

- Ndukwe, C.; Idike, A.N.; Ukeje, I.O.; Okorie, C.O.; Onele, J.C.; Richard-Nnabu, N.E.; Kanu, C.; Okezie, B.N.; Ekwunife, A.; Nweke, C.J.; et al. Public private partnerships dynamics in Nigeria power sector: Service failure outcomes and consumer dissonance behaviour. Public Organ. Rev. 2023, 23, 623–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, A. Consumer Landscape in 2023. Euromonitor International. Available online: https://www.euromonitor.com/article/consumer-landscape-in-2023 (accessed on 28 September 2023).

- Song, C.; Xu, B.; Xu, L. Dual-channel supply chain pricing decisions for low-carbon consumer: A rewire. J. Intell. Manag. Discuss. 2023, 2, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, N.; Mishra, I. Responsible consumption and production: A roadmap to sustainable development. Environ. Sustain. 2023, 6, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, S.T. The sharing economy and collaborative consumption: Strategic issues and global entrepreneurial opportunities. J. Int. Entrep. 2023, 21, 60–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat. Consumers’ Behaviour Related to Online Purchases. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/ISOC_EC_IBHV__custom_6658988/default/table?lang=en (accessed on 28 September 2023).

- Eurostat. E-Commerce Statistics for Individuals. Eurostat Statistics Explained. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=E-commerce_statistics_for_individuals (accessed on 28 September 2023).

- Eurostat. Internet Purchases-Collaborative Economy (2020 Onwards). Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/ISOC_EC_CE_I__custom_5044323/bookmark/table?lang=en&bookmarkId=02fc72d1-019d-48df-8720-7b1b0a8d22be (accessed on 28 September 2023).

- Akbar, P.; Hoffmann, S. Collaborative space: Framework for collaborative consumption and the sharing economy. J. Serv. Mark. 2022, 37, 496–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamari, J.; Sjöklint, M.; Ukkonen, A. The sharing economy: Why people participate in collaborative consumption. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2016, 67, 2047–2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daglis, T. Sharing economy. Encyclopedia 2022, 2, 1322–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Rodríguez, F.J.; Gutiérrez-Taño, D.; Ruiz-Rosa, I.; Baute-Díaz, N. New models for collaborative consumption: The role of consumer attitudes among millennials. SAGE Open 2022, 12, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, A.C.; Soares, R.R.; Proença, J.F. Motivations for peer-to-peer accommodation: Exploring sustainable choices in collaborative consumption. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Yuan, H.; Dong, X.; Chen, Z.; Zhou, L. Social norms and socially responsible consumption behavior in the sharing economy: The mediation role of reciprocity motivation. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 414, 137750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, N. The regulation of the collaborative economy in the European Union. Unio 2019, 5, 40–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatarinov, K.; Ambos, T.C.; Tschang, F.T. Scaling digital solutions for wicked problems: Ecosystem versatility. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2023, 54, 631–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menor-Campos, A.; García-Moreno, M.D.L.B.; López-Guzmán, T.; Hidalgo-Fernández, A. Effects of collaborative economy: A reflection. Soc. Sci. 2019, 8, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Y.; Wang, Y.; Hajli, S.; Featherman, M. In sharing economy we trust: Examining the effect of social and technical enablers on millennials’ trust in sharing commerce. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 108, 105993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharmaa, A.; Jain, R.; Pajni, N. Risk identification techniques in retail industry: A case study of Tesko PLc. J. Corp. Gov. Insur. Risk Manag. 2021, 9, 201–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.; Wang, D.; Zhang, F.; Xu, B.; Ouyang, Z. A multi-criteria group decision-making method for risk assessment of live-streaming E-Commerce platform. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2023, 18, 1126–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pankov, S.; Velamuri, V.K.; Schneckenberg, D. Towards sustainable entrepreneurial ecosystems: Examining the effect of contextual factors on sustainable entrepreneurial activities in the sharing economy. Small Bus. Econ. 2021, 56, 1073–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nukusheva, A.; Rustembekova, D.; Abdizhami, A.; Au, T.; Kozhantayeva, Z. Regulatory obstacles in municipal solid waste management in Kazakhstan in comparison with the EU. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rughiniş, C.; Flaherty, M.G. The social bifurcation of reality: Symmetrical construction of knowledge in science-trusting and science-distrusting discourses. Front. Sociol. 2022, 7, 782851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, R. The Sharing Economy: Definition, Examples and Advantages. Climate Consulting Selectra. Available online: https://climate.selectra.com/en/environment/sharing-economy (accessed on 28 September 2023).

- Minami, A.L.; Ramos, C.; Bortoluzzo, A.B. Sharing economy versus collaborative consumption: What drives consumers in the new forms of exchange? J. Bus. Res. 2021, 128, 124–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Items related to consumer behavior variables | Age group: | |||||

| 16–24 | 25–34 | 35–44 | 45–54 | 55–74 | ||

| 26% | 35% | 33% | 24% | 14% | ||

| Education: | ||||||

| No or low formal education | Medium formal education | High formal education | ||||

| 15% | 23% | 34% | ||||

| The economic status of buyers: | ||||||

| Retired | Employees, entrepreneurs | Students | Unemployed | |||

| 14% | 29% | 26% | 20% | |||

| Origins of internet consumers: | ||||||

| Residents of other EU member states | Residents of a non-EU state | Local online shoppers | ||||

| 24% | 19% | 26% | ||||

| Consumer behavior related to online shopping: | ||||||

| Analyzing prices or products every time before purchasing/ordering online | Using customer reviews on websites or blogs every time before purchasing/ordering online | Using information from the websites of several sellers, manufacturers, and service providers before purchasing/ordering online | Rarely or never using information from websites of multiple sellers, manufacturers, and service providers before purchasing/ordering online | Online purchasing/ordering by clicking/purchasing immediately through the website or social media app advertizing | ||

| 49.5% | 22.3% | 14.9% | 9.0% | 4.3% | ||

| Elements related to sustainable consumption | Sustainable consumption: | |||||

| Resource utilization efficiency | Circular use of materials | Reducing global waste | ||||

| 2019–2021 −0.8 tons per capita (14.4–13.6) | 2019–2021 −0.3% (12.0%–11.7%) | 2019–2021 −0.4 kg per capita (5.2–4.8) | ||||

| Transaction Payment (TP) = Collaborative Economy (CE) + Digital Platform (GP) | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gerlich, M. The Rise of Collaborative Consumption in EU Member States: Exploring the Impact of Collaborative Economy Platforms on Consumer Behavior and Sustainable Consumption. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15491. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152115491

Gerlich M. The Rise of Collaborative Consumption in EU Member States: Exploring the Impact of Collaborative Economy Platforms on Consumer Behavior and Sustainable Consumption. Sustainability. 2023; 15(21):15491. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152115491

Chicago/Turabian StyleGerlich, Michael. 2023. "The Rise of Collaborative Consumption in EU Member States: Exploring the Impact of Collaborative Economy Platforms on Consumer Behavior and Sustainable Consumption" Sustainability 15, no. 21: 15491. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152115491

APA StyleGerlich, M. (2023). The Rise of Collaborative Consumption in EU Member States: Exploring the Impact of Collaborative Economy Platforms on Consumer Behavior and Sustainable Consumption. Sustainability, 15(21), 15491. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152115491