Analysis of Chinese National Standards on Packaging and the Environment (CNSPE) Based on Standard Literature Bibliometrics

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Source

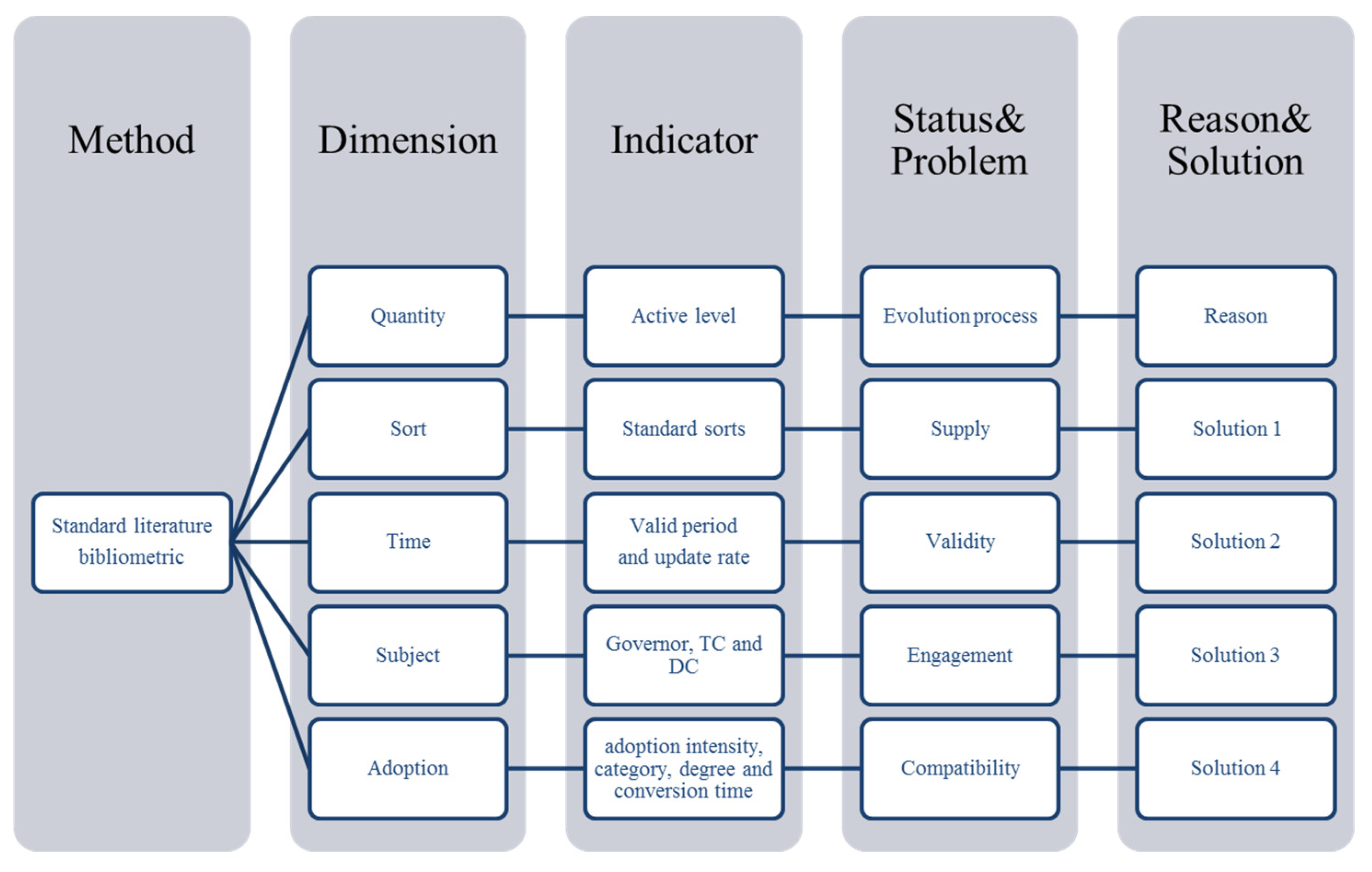

2.2. Research Design and Framework

2.3. Indicators and Analysis Methods

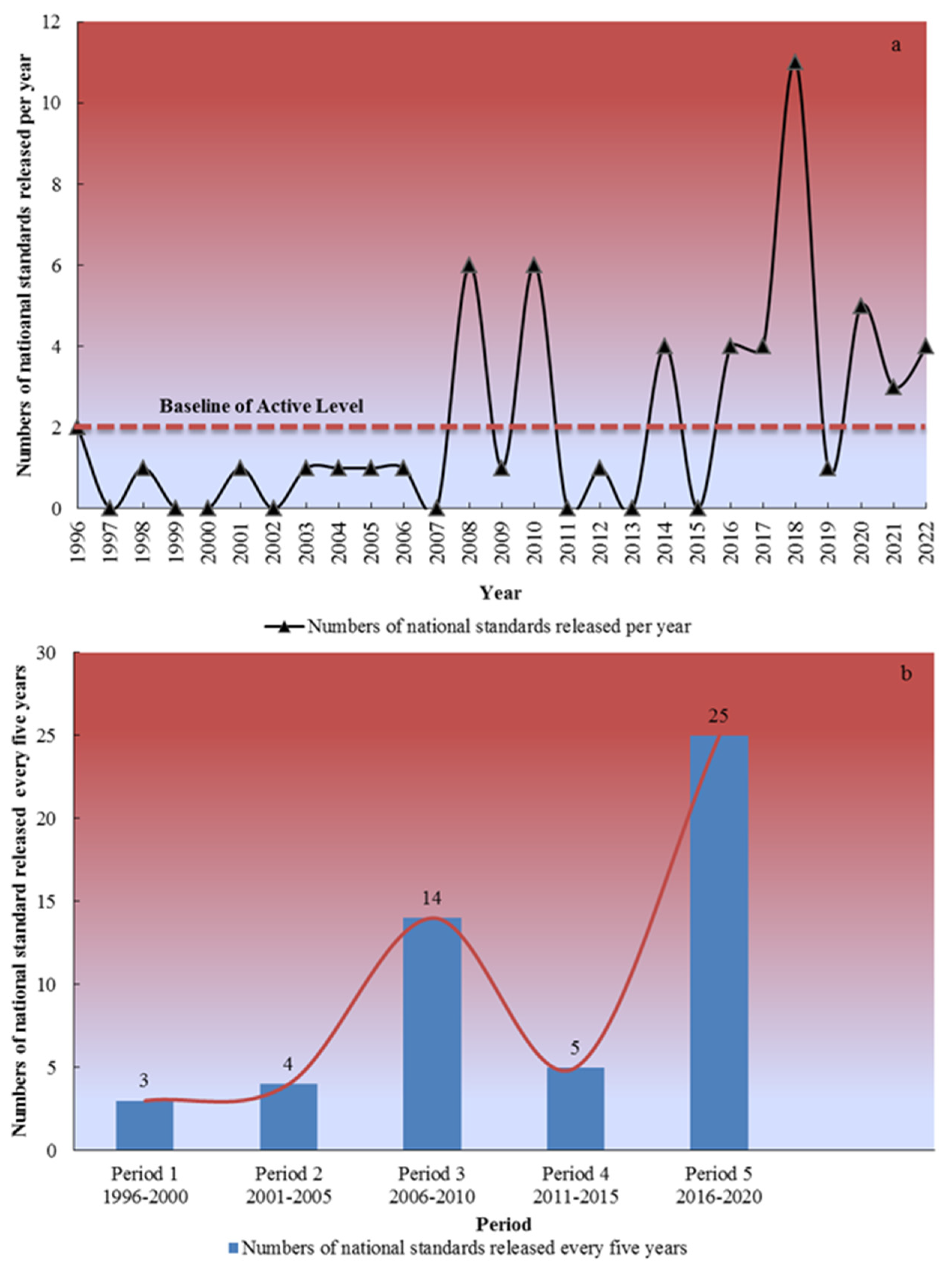

2.3.1. Active Level of Developing Standards

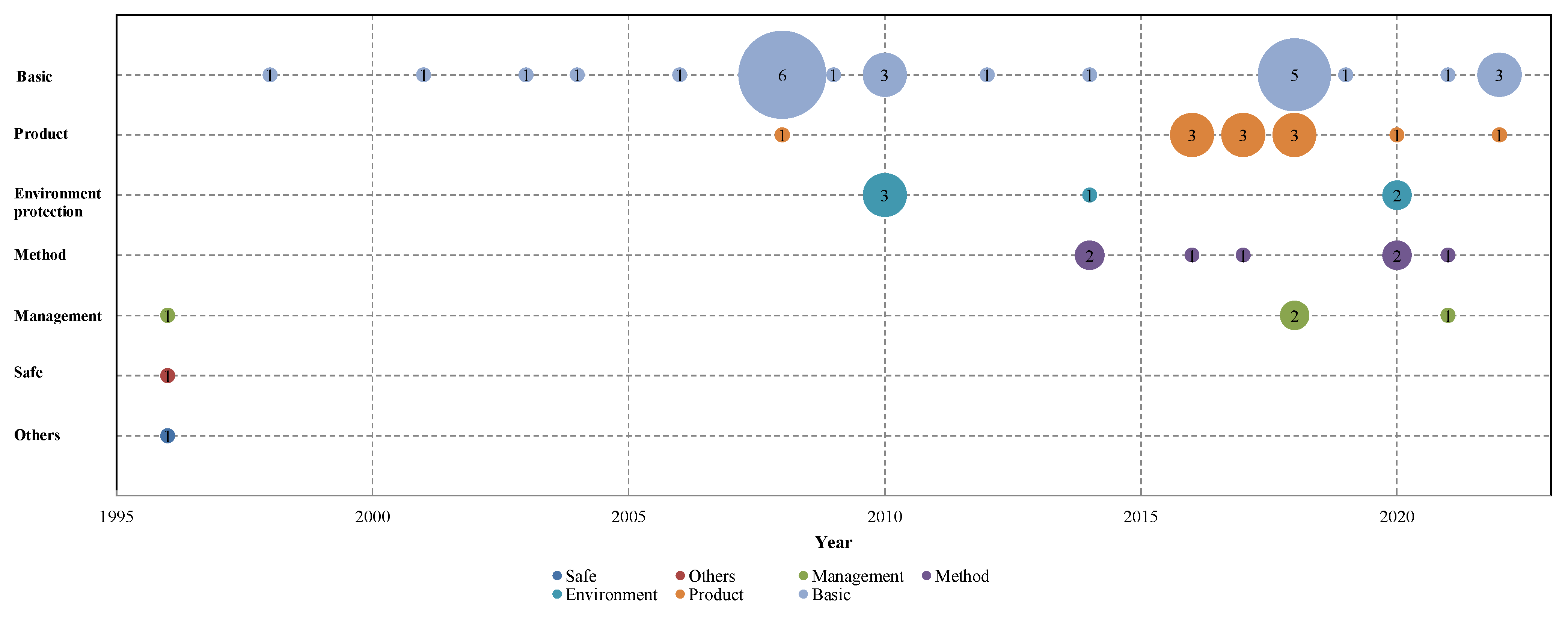

2.3.2. Standards Sort

2.3.3. Valid Periods and Update Rates of Standards

2.3.4. Governor, Technical Committees and Draft Committees

2.3.5. Adoption of International or Foreign Standards

3. Results

3.1. Active Level of Developing Standards

3.2. Standard Sorts

3.3. Valid Periods and Update Rates of Standards

3.4. Governor, Technical Committees and Draft Committees of Standards

3.5. Adoption of International or Foreign Standards

4. Discussion

4.1. Evolution Process of the CNSPE

4.2. Analysis on the Existing Chinese Standard System on Packaging and the Environment

4.3. Proposals and Solutions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- ISO 18601-2013; Packaging and the Environment—General Requirements for the Use of ISO Standard in the Field of Packaging. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013.

- Zhou, W.; Huang, W. Contract designs for energy-saving product development in a monopoly. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2016, 250, 902–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahladakis, J.N.; Iacovidou, E. Closing the loop on plastic packaging materials: What is quality and how does it affect their circularity? Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 630, 1394–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ada, E.; Kazancoglu, Y.; Gozacan-Chase, N.; Altin, O. Challenges for circular food packaging: Circular resources utilization. Appl. Food Res. 2023, 3, 100310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation; McKinsey & Co. The New Plastics Economy: Rethinking the Future of Plastics. Available online: https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/assets/downloads/EllenMacArthurFoundation_TheNewPlasticsEconomy_Pages.pdf (accessed on 30 August 2023).

- Ilyas, M.; Ahmad, W.; Khan, H.; Yousaf, S.; Khan, K.; Nazir, S. Plastic waste as a significant threat to environment—A systematic literature review. Rev. Environ. Health 2018, 33, 383–406. [Google Scholar]

- Seungtaek, L.; Jonghoon, K.; Wai, O.C. The causes of the municipal solid waste and the greenhouse gas emissions from the waste sector in the United States. Proced. Eng. 2016, 145, 1074–1079. [Google Scholar]

- WRAP Plastic Packaging. Available online: https://wrap.org.uk/taking-action/plastic-packaging (accessed on 30 August 2023).

- Ingarao, G.; Licata, S.; Sciortino, M.; Planeta, D.; Di Lorenzo, R.; Fratini, L. Life cycle energy and CO2 emissions analysis of food packaging: An insight into the methodology from an Italian perspective. Int. J. Sustain. Eng. 2017, 10, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonopoulos, I.; Faraca, G.; Tonini, D. Recycling of post-consumer plastic packaging waste in the EU: Recovery rates, material flows, and barriers. Waste Manag. 2021, 126, 694–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. The Future of Food and Agriculture—Trends and Challenges; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2017; Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/i6583e/i6583e.pdf (accessed on 30 August 2023).

- FoodDrinkEurope. Data and Trends. EU Food and Drink Industry. 2021. Available online: https://www.fooddrinkeurope.eu/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/FoodDrinkEurope-Data-Trends-2021-digital.pdf (accessed on 30 August 2023).

- European Commission. Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on Packaging and Packaging Waste, Amending Regulation (EU) 2019/1020 and Directive (EU) 2019/904, and Repealing Directive 94/62/EC. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ALL/?uri=CELEX%3A52022PC0677 (accessed on 30 August 2023).

- PlasticEurope Plastics—The Facts. 2020. Available online: https://www.plasticseurope.org/en/resources/market-data (accessed on 30 August 2023).

- National Bureau of Statistics. China Statistical Yearbook; China Statistics Press: Beijing, China, 2022. Available online: http://www.stats.gov.cn/sj/ndsj/2022/indexeh.htm (accessed on 30 August 2023).

- ISO. ISO Strategy 2030. Available online: https://www.iso.org/files/live/sites/isoorg/files/store/en/PUB100364.pdf (accessed on 30 August 2023).

- ISO. Contributing to the UN Sustainable Development Goals with ISO Standards. Available online: https://www.iso.org/files/live/sites/isoorg/files/store/en/PUB100429.pdf (accessed on 30 August 2023).

- McKinsey. True Packaging Sustainability: Understanding the Performance Trade-Offs. 2021. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.de/industries/paper-forest-products-and-packaging/our-insights/true-packaging-sustainability-understanding-the-performance-trade-offs (accessed on 30 August 2023).

- European Commission. Waste Framework Directive. 2022. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/environment/topics/waste-and-recycling/waste-framework-directive_en (accessed on 30 August 2023).

- Commission Communication in the Framework of the Implementation of the European Parliament and Council Directive 94/62/EC of 20 December 1994 on Packaging and Packaging Waste. Official Journal of the European Union. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52005XC0219(02) (accessed on 30 August 2023).

- ISO/TC 122/SC 4; Packaging and the Environment. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2005. Available online: https://www.iso.org/committee/52082.html (accessed on 30 August 2023).

- Xu, Y.H.; Guo, Z.M.; Zhang, G.; Wang, X.; Shen, W.J. International Convergence of “Packaging and Environment” Standardization System. Packaging Eng. 2016, 37, 58–62. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, J. Analysis of Paths for Improving Laws and Regulations on Logistics Packaging. Logist. Technol. 2012, 31, 199. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, K.; Jiang, W.Y.; Chen, Y.L.; Qian, L.F. Legislative Suggestion to the Governance of E-commerce Express Packaging Waste in China. J. GuiZhou Univ. 2020, 38, 95–103. [Google Scholar]

- China Packaging Federation. Overview of Import and Export of Packaging Industry in March 2022. Available online: http://www.cpf.org.cn/product/164.html (accessed on 30 August 2023).

- Tan, M.L.; Jiang, J. Bibliometric analysis of domestic text mining from 2010 to 2021. Digit. Technol. Applicat. 2023, 41, 26–30. [Google Scholar]

- Ledesma, F. Bibliometric Indicators and Decision Making. Data Metadata 2022, 1, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aria, M.; Cuccurullo, C. bibliometrix: An R-tool for comprehensive science mapping analysis. J. Informetr. 2017, 11, 959–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.P. Research on the Measurement and Analysis Method of Standards and its Agricultural Applications; Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences: Beijing, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, K. Bibliometric Analysis of China’s Science and Technology Archives Standards. Jidian Bing Chuan Dang An. 2018, 1, 66–70. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, P.T.; Xu, W. Research on standardization of publishing industry based on standard bibliometrics. Res. Educat. 2019, 298, 116–124. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, G.C.; Liu, J. A Comparative Study of Chinese and ISO Information Security Standards. J. Intel. 2022, 41, 184. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.M.; Li, Y.L.; Liu, W.L.; Dong, Z.X.; Zhang, C.D.; He, M.M. Analysis and Study of China’s Medical Insurance Drug Payment Standards from the Perspective of Bibliometry. China Health Insur. 2023, 2, 92–99. [Google Scholar]

- ISO/IEC Guide 21-1 Regional or National Adoption of International Standards and Other International Deliverables—Part 1: Adoption of International Standards. Available online: https://www.iso.org/home.isoDocumentsDownload.do?t=oE9d-zmo_9043bwk_9K0lxTRpXSVOBdLY2yRQL7kW0y_Jf3IL-XW7c_fTeAb_F6D&CSRFTOKEN=L45D-0PN0-B690-H3GK-KF1B-UNFC-UDMS-4PO6 (accessed on 30 August 2023).

- European Commission. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Eco-nomic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. A Resource-Efficient Europe—Flagship Initiative under the Europe, COM (2011). 2020. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/policy-documents/a-resource-efficient-europe-flagship (accessed on 30 August 2023).

- Marco-Fondevila, M.; Llena-Macarulla, F.; Callao-Gastón, S.; Jarne-Jarne, J. Are circular economy policies actually reaching organizations? Evidence from the largest Spanish companies. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 285, 124858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 18602–2013; Packaging and the environment—Optimization of the packaging system. International Standard Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013.

- ISO 18603–2013; Packaging and the Environment—Reuse. International Standard Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013.

- ISO 18604–2013; Packaging and the Environment—Material Recycling. International Standard Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013.

- ISO 18605–2013; Packaging and the Environment—Energy Recovery. International Standard Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013.

- ISO 18606–2013; Packaging and the Environment—Organic Recycling. International Standard Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013.

- The national packaging industry “ninth Five-Year” development plan and long-term development goals in 2010. China Packag. 1996, 16, 16–20.

- The national packaging industry “ten Five-Year” development plan and long-term development goals in 2015. China Packag. News, 27 April 2001.

- Packaging Industry “Twelfth Five-Year Plan” Analysis and Investment Prospects Forecast Research Report. 2011.

- Ding, S.; Gao, Y.X.; Gao, D.F. Study on Legislation, Policies and Standards related to Packaging and Packaging Waste Management in China and European Union. China Standardizat. 2023, 6, 93–99. [Google Scholar]

- The General Office of the State Council Forwarded the Notice of the National Development and Reform Commission and Other Departments on Accelerating the Green Transformation of Express Packaging. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2020-12/14/content_5569345.htm (accessed on 30 August 2023).

- Notice of The General Office of the State Council on Further Strengthening the Control of Excessive Packaging of Commodities. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/2022-09/08/content_5708858.htm (accessed on 30 August 2023).

- China Issues Guideline to Deepen Reform of Standardization System. Available online: http://english.www.gov.cn/policies/latest_releases/2015/03/26/content_281475078008940.htm (accessed on 26 March 2015).

- T/CIET 074–2023; General Principles for Green Packaging Evaluation. China Association for Promoting International Econimic & Technical Cooperation: Beijing, China, 2023.

- GB 23350–2021; Requirements of Restricting Excessive Package–Food and Cosmetics. State Administration for Market Regulation: Beijing, China, 2021.

| Standard Status | Number | Proportion (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Released but not be executed | 1 | 2 |

| Currently valid but be replaced soon | 1 | 2 |

| Currently valid | 41 | 70 |

| Abolished | 15 | 26 |

| Valid Period(Tv)/(Year) | Number | Proportion/(%) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 ≤ Tv ≤ 5 | 23 | 54.76 |

| 5 < Tv ≤ 10 | 13 | 30.95 |

| 10 < Tv ≤ 15 | 5 | 11.91 |

| 15 < Tv ≤ 20 | 1 | 2.38 |

| Governor | Number | Proportion/(%) |

|---|---|---|

| Standardization Administration of P.R.C. (SAC) | 39 | 67.24 |

| Ministry of Industry and Information Technology | 5 | 8.62 |

| Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs | 2 | 3.45 |

| Ministry of Commerce | 1 | 1.72 |

| State Post Bureau | 4 | 6.90 |

| China National Light Industry Council | 5 | 8.62 |

| China Petroleum and Chemical Industry Federation | 2 | 3.45 |

| Type of Draft Committees | Standard Quantity | Proportion/(%) |

|---|---|---|

| Public institution | 33 | 53.45 |

| Enterprise | 26 | 43.85 |

| Social group | 1 | 1.72 |

| Conversion Time Tc/(Year) | Number | Proportion/(%) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 ≤ Tc ≤ 5 | 1 | 5.56 |

| 5 < Tc ≤ 10 | 14 | 77.77 |

| 10 < Tc ≤ 15 | 3 | 16.67 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ding, S.; Gao, Y.; Lin, H.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, R.; Lin, L.; Xu, B.; Gao, D. Analysis of Chinese National Standards on Packaging and the Environment (CNSPE) Based on Standard Literature Bibliometrics. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15385. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152115385

Ding S, Gao Y, Lin H, Zhu Y, Zhang R, Lin L, Xu B, Gao D. Analysis of Chinese National Standards on Packaging and the Environment (CNSPE) Based on Standard Literature Bibliometrics. Sustainability. 2023; 15(21):15385. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152115385

Chicago/Turabian StyleDing, Shuang, Yanxin Gao, Haoxin Lin, Yi Zhu, Rui Zhang, Ling Lin, Bingsheng Xu, and Dongfeng Gao. 2023. "Analysis of Chinese National Standards on Packaging and the Environment (CNSPE) Based on Standard Literature Bibliometrics" Sustainability 15, no. 21: 15385. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152115385

APA StyleDing, S., Gao, Y., Lin, H., Zhu, Y., Zhang, R., Lin, L., Xu, B., & Gao, D. (2023). Analysis of Chinese National Standards on Packaging and the Environment (CNSPE) Based on Standard Literature Bibliometrics. Sustainability, 15(21), 15385. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152115385