Sustainable Small Ruminant Production in Low- and Middle-Income African Countries: Harnessing the Potential of Agroecology

Abstract

1. Introduction

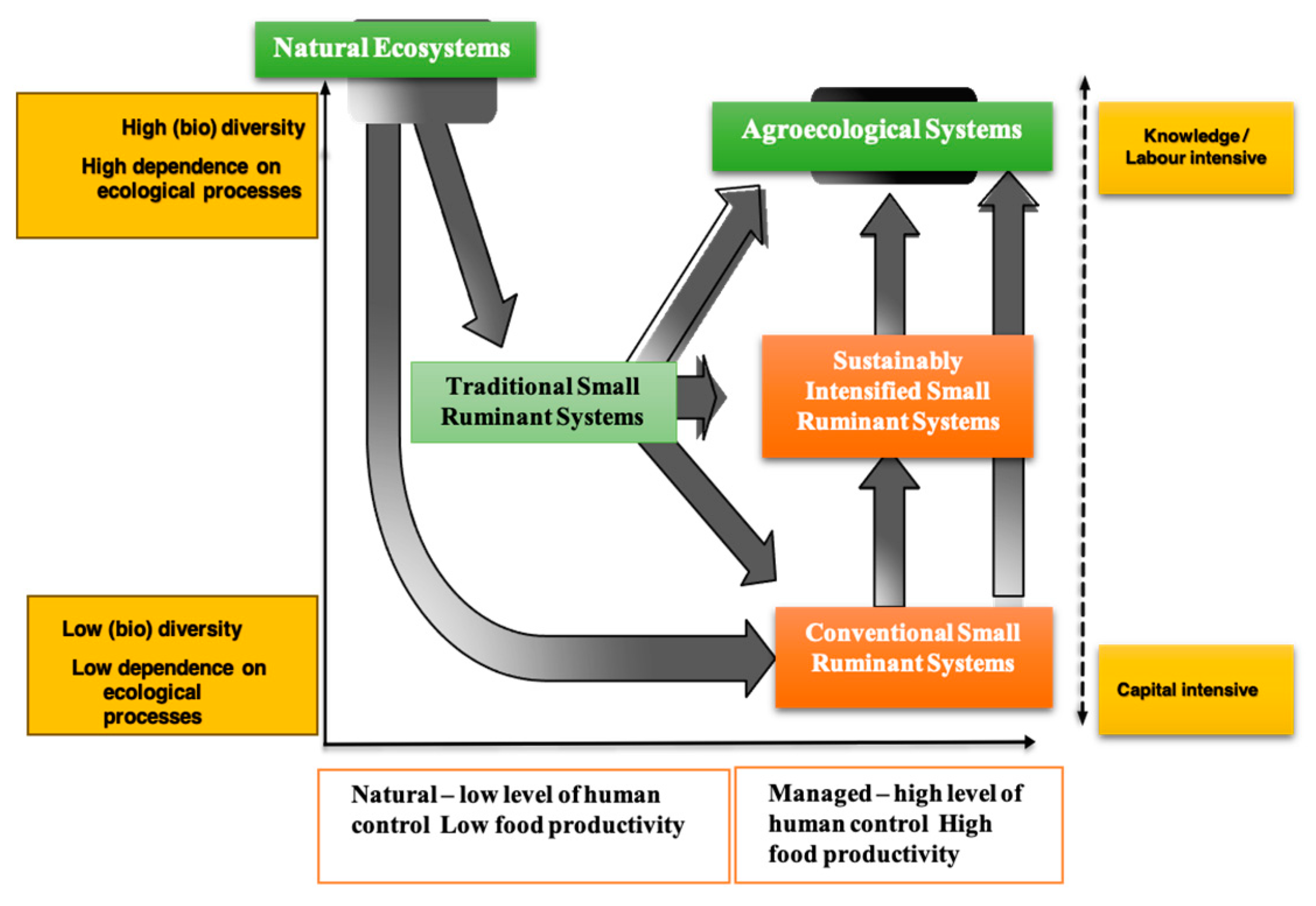

2. The Pathway to an Agroecosystem in Small Ruminant Production

3. Concept of Circularity in Small Ruminant Livestock Production Systems

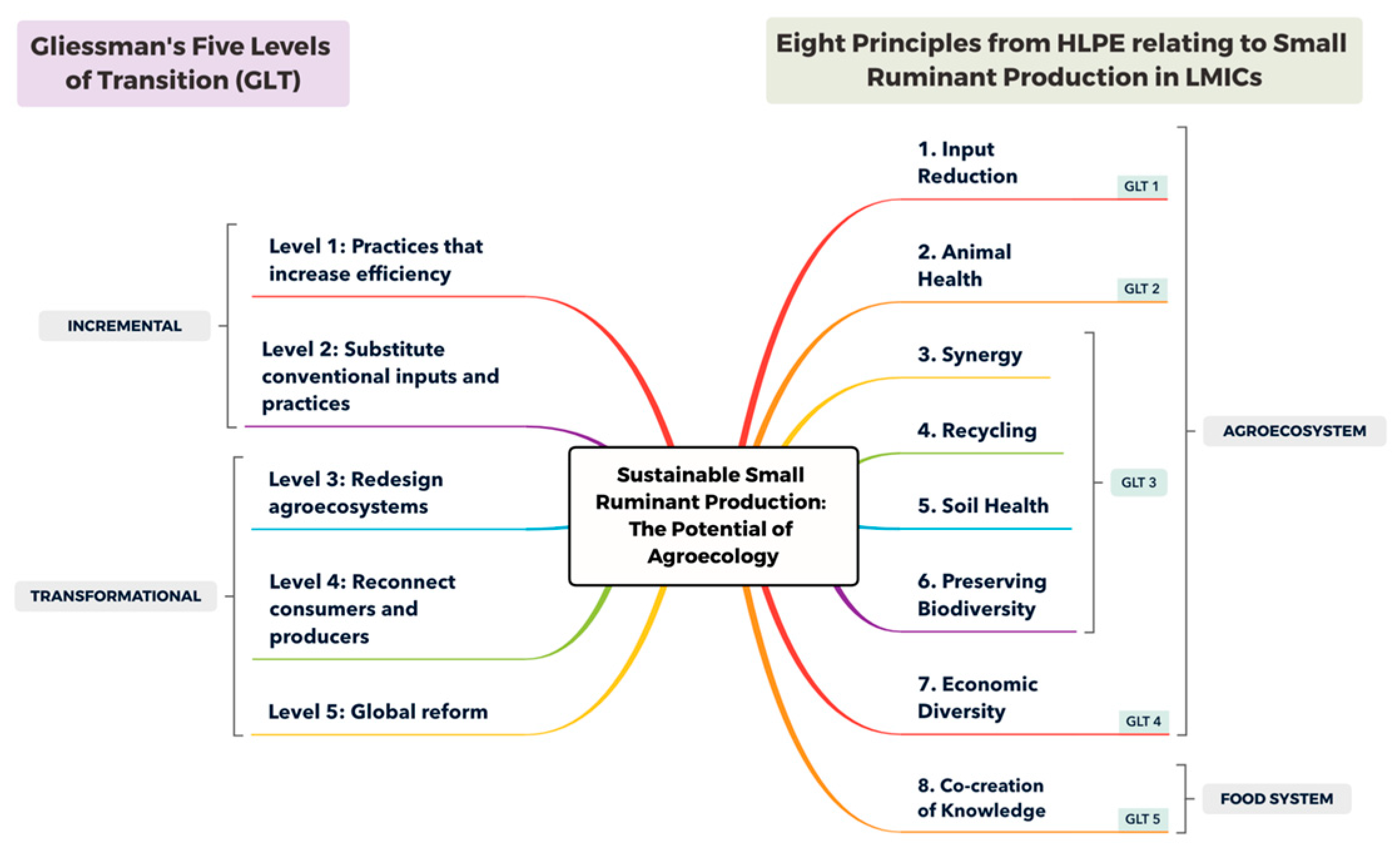

4. Gliessman’s Five Levels of Transition (GLT) Pathways and Related Agroecological Principles as Applied to Small Ruminant Production Systems

4.1. Level 1: Practices That Increase Efficiency and the Principle of Input Reduction

| Country(s) of Study | Aim(s) of Study | Main Finding(s) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Push–Pull Technology (PPT) | |||

| Kenya | Assess the impacts of PPT adoption on economic and social welfare. | Maize yield increased in PPT plots compared to non-PPT plots. PPT system benefitted fodder production through direct sales and livestock products. | [69] |

| Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania | Assess climate-smart PPT’s impact on maize infestation and farmers’ perceptions of its effectiveness in east Africa against fall armyworm. | Fall armyworm infestation in East Africa was reduced using climate-adapted push–pull system, reducing maize damage and boosting farmers’ perceptions of its effectiveness. | [70] |

| Uganda | Assess PPT adoption’s impact on Ugandan smallholder farmers’ welfare. | With the expansion of PPT land, average maize grain production (kg/unit land area), average household income, and average per capita food intake increased. | [71] |

| Kenya | Compare the performance of PPT to common maize-based cropping systems. | PPT enhanced grain yield, biomass productivity, and reduced weed infestation. | [72] |

| Ethiopia | Contrast the robustness of PPT farming systems with that of conventional farming systems. | No evidence of positive impact of PPT on pest and weed control due to lack of a severe weed infestation. PPT improved fodder production but not maize yield. | [73] |

| Kenya, Tanzania, Ethiopia | Assess farmers’ readiness to adopt climate-smart PPT in eastern Africa, including knowledge dissemination strategies and projected impact. | Financial analysis showed positive technology benefits from controlled Striga and stemborers, improving soil fertility, outweighing costs compared to farmers’ practices, and improving cereal yields. | [74] |

| Ethiopia | Evaluate push–pull systems’ agronomic and pest suppression potential in complex landscapes with companion crops. | Push–pull helped decrease stemborer infestation in intermediate-complexity landscapes with no dominant host plants or perennials. Common bean repelled stemborer effectively, potentially replacing Desmodium in areas with Striga infestations. It increased general predator abundance and egg predation rate compared to solely maize or maize intercropped with Desmodium. | [75] |

| Kenya | Compare male and female field plots to examine the adoption of push–pull pest management technology and sustainable farming practices in western Kenya. | Econometric analysis showed no gender heterogeneity in PPT adoption. Jointly managed plots received more animal manure, soil, and water conservation measures. There were no gender differences in intercropping, crop rotation, or fertilizer use. The analysis showed a considerable association between PPT and agricultural technology, implying equal promotion. | [76] |

| Malawi | Examine PPT performance in different agroecological zones. | Study confirmed the benefits of technology in terms of stemborer and Striga control. | [77] |

| Manure Application | |||

| Nigeria | Assess NPK fertilizer and poultry manure’s impact on cassava, maize, and melon yields. | Poultry manure and chemical fertilizer produced higher yields than sole application of each. | [78] |

| Zimbabwe | Examine the impact of cattle manure and inorganic fertilizer on maize yield. | Compared to control treatments, applying 2.5 t/ha cattle manure enhanced grain weight, grain, and stover yields by 29.7 percent. Continuous manure application at 5.0 t/ha with no inorganic fertilizer considerably improved yields. The combined treatments outperformed the separate treatments in terms of yield. | [79] |

| Senegal | Analyze the impact of organic and mineral fertilizer on weed flora in a peanut crop. | Weed density was unaffected by fertilization type. Cattle manure treatment had the highest dry weight of grasses at 40 days, followed by inorganic fertilizer at 15.2 g/m. | [80] |

| Not applicable | Discuss the components of integrated nutrition management and their impact on maize crop productivity. | Compared to the solo use of organic and inorganic fertilizers, integrated nutrient management improved maize production, absorption of nutrients, and economic return. | [81] |

| Uganda | Evaluate cattle manure and inorganic fertilizer usage in central Ugandan smallholder farms. | Cattle manure application resulted in high yields and reduced production costs. Major problems of cattle manure use included weight and bulkiness, labor, insufficient quantities, and high transportation and application costs. Most farmers supplemented with other animal manures but never used inorganic fertilizer due to costs and lack of capital. | [82] |

| Nigeria | Evaluate maize growth and yield using fortified organic fertilizers vs. inorganic fertilization. | Combining poultry manure and chemical fertilizer improved maize nutrient availability and performance. | [83] |

| Nigeria | Examine the impact of combining ammonium nitrate and goat manure treatment on soil nutrient availability and okra performance. | The highest plant height, leaf area, and leaf count were reached using 8 t/ha−1 goat manure + 200 kg/ha−1 urea fertilizer. With 8 t/ha−1 goat manure + 200 kg/ha−1 urea fertilizer, there was a significant increase in fruit weight, flowering days, number, diameter, and length. | [84] |

| Ethiopia | Evaluate the impact of cow manure and inorganic fertilizer on potato growth and yield. | Integrated farmyard manure and commercial NP fertilizers improved potato tuber yield, potentially reducing production costs. The integrated approach enhanced soil properties for sustainable crop production. | [85] |

| Uganda | Examine combined cattle manure and mineral fertilizers on Pennisetum purpureum fodder growth characteristics. | Sole application of composted cattle manure or combination with mineral fertilizers improved the growth of Pennisetum purpureum fodder. Cattle manure and mineral fertilizers produced similar fodder quantities. A combination of composted cattle manure and mineral fertilizers reduced fertilizer costs. | [86] |

| Kenya | Investigate the long-term impacts of organic and inorganic soil fertilization on soil organic matter content functional groups and the relationship between the composition of soil organic matter content functional groups and maize (Zea mays) grain yields. | Long-term use of organic fertilizers alone or combined with inorganic fertilizers increased maize yield and soil C sequestration potential. | [87] |

| Kenya | Measure soil greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in central Kenya using static chambers during maize cropping seasons with four soil amendment treatments: animal manure, inorganic fertilizer, mixed manure, and no N control. | Animal manure amendment increased CO2 emissions, N2O emissions, and maize yields but had the lowest N2O yield-scaled emissions. Manure and inorganic fertilizer significantly increased CH4 uptake and N2O yield-scaled emissions. While animal manure may raise total GHG emissions, the concurrent rise in maize yields resulted in lower yield-scaled GHG emissions. | [88] |

| Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, Malawi, Nigeria, Rwanda, Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia, Zimbabwe | Quantify increased grain yield, rain usage efficiency, and nitrogen (AEN) and phosphorus (AEP) agronomic efficiency through integrated soil fertility management (ISFM). Determine ideal soil fertility management conditions. Contrast yield responses to soil fertility management with and without the use of cattle manure only. | ISFM treatments improved grain yields by 3 t ha−1 more than cattle dung or inorganic fertilizer alone. Compared to greater application rates, sole application of cattle dung produced lower yields but higher AEN and AEP. | [89] |

| Ethiopia | Review the contribution of integrated nutrient management practices for sustainable maize crop productivity. | Combined application of inorganic fertilizers with different sources of organic manures enhanced crop productivity, nutrient uptake, and soil nutrient status in maize-based cropping systems. | [90] |

| Egypt | Examine different fertilizer effects on maize yield growth, productivity, and quality. | Organic materials yielded more, and combined use reduced chemical fertilizer costs and environmental hazards. Best practice: use of a combination of sheep manure, compost, and Ureaform to achieve high maize growth, yield, and quality and improved soil properties | [91] |

4.2. Level 2: Substitution of Agroecological Inputs and Practices and the Principle of Improving Animal Health

| Strategy | Interventions | Impact | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Farming system | Multispecies livestock system, rotational grazing | Cograzing lambs with cattle reduced nematode eggs and gastrointestinal nematode excretion; rotational grazing reduced fecal egg excretion and mortality. | [107,108] |

| Organic acids | Use of formic acid, fumaric acid, malic acid, formic acid, and their combinations | Reduced ruminal microbiota, digestibility, and proteolysis while increasing methane emission and total gas production. | [109,110] |

| Plant bioactive compounds | Use of condensed tannins, medicinal plants, chicory | Improved feed intake, growth, immunity, and reproduction and reduced emissions and parasitism. | [92,98,111,112] |

| Probiotics and prebiotics | Use of direct-fed microbials (DFMs), Rumen Enhancer (RE)3, lactic acid bacteria as putative probiotic, dry yeast with viable yeast cell | Enhanced ruminal acidosis, immune response, gut health, and productivity and reduced pathogen emissions; maintained balance, improved growth performance, and potentially replaced antibiotics. | [94,95,113,114,115,116,117,118] |

4.3. Level 3: Redesigning Agroecosystems

4.3.1. The Principles of Preserving Biodiversity, Synergy, and Soil Health in Redesigning Agroecosystems

4.3.2. Redesigning Agroecosystems and the Principle of Recycling

4.4. Level 4: Reconnecting Producers and Consumers and the Principles of Economic Diversity and Cocreation of Knowledge

4.5. Level 5: Global Reform and the Principle of Cocreation of Knowledge

5. Perspective on Agroecological Principles Applied to Small Ruminant Systems in Low- and Middle-Income Countries

- (i)

- Skills and capacity building: Strengthening local communities through specialized training programs is critical for unlocking the potential of agroecology in small ruminant farming in African countries. These programs provide practical knowledge to farmers, extension workers, and practitioners, focusing on sustainable livestock management, natural remedies, and ecofriendly pest control techniques. By imparting these skills, individuals can implement agroecological practices effectively, promoting environmentally friendly methods in small ruminant production.

- (ii)

- Research-based knowledge generation: Investing in research focused on traditional natural remedies is vital. Rigorous scientific studies validate indigenous knowledge, refine traditional practices, and enhance their effectiveness. Collaborative research involving researchers and farmers ensures that valuable traditional knowledge is preserved and improved. Sharing research findings through accessible channels equips farmers with practical, evidence-based information, enabling them to use effective natural remedies in small ruminant farming.

- (iii)

- Appropriate technologies: In overcoming challenges in harnessing agroecology for small ruminant production, a strategic focus on appropriate technology is key. Implementing fodder choppers, feed millers, and solar-powered devices ensures sustainable practices. Cooperative-owned machinery use enhances efficiency and accessibility, and it becomes an incentive for further use for other community farmers who may not be preview to its benefits. Education and training programs empower farmers to operate and maintain machinery, while community-owned cooperatives make equipment collectively accessible. Encouraging local innovations fosters tailored solutions and promotes sustainability and productivity in small ruminant farming.

- (iv)

- Knowledge exchange networks and policy support: Creating platforms for sharing knowledge and supportive policies are fundamental. Forums connecting farmers, researchers, and policymakers allow the exchange of best practices. Farmer cooperatives and community-based organizations serve as valuable hubs for sharing knowledge. Policymakers’ roles are crucial: policies encouraging sustainable practices and providing financial support create a conducive environment. When these policies align with local needs, they promote the widespread adoption of agroecological methods in small ruminant farming across Africa.

6. Concluding Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adams, F.; Ohene-Yankyera, K.; Aidoo, R.; Wongnaa, C.A. Economic benefits of livestock management in Ghana. Agric. Food Econ. 2021, 9, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, F.; Ohene-Yankyera, K. Socio-economic characteristics of subsistent small ruminant farmers in three regions of northern Ghana. Asian J. Appl. Sci. Eng. 2014, 3, 351–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alders, R.G.; Campbell, A.; Costa, R.; Guèye, E.F.; Ahasanul Hoque, M.; Perezgrovas-Garza, R.; Rota, A.; Wingett, K. Livestock across the world: Diverse animal species with complex roles in human societies and ecosystem services. Anim. Front. 2021, 11, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Live Animals—Slaughtering: Number Slaughtered. Available online: http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QL (accessed on 10 February 2023).

- Iñiguez, L. The challenges of research and development of small ruminant production in dry areas. Small Rumin. Res. 2011, 98, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosgey, I.S.; Rowlands, G.J.; van Arendonk, J.A.M.; Baker, R.L. Small ruminant production in smallholder and pastoral/extensive farming systems in Kenya. Small Rumin. Res. 2008, 77, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, F.; Ohene-Yankyera, K. Looking Beyond the Market: Estimating the Economic Benefits of Managing Small Ruminants in Two Agro-Ecological Zones of Ghana. In Proceedings of Conference on Inclusive Growth and Poverty Reduction in the IGAD Region; IGAD: Djibouti City, Djibouti, 2016; p. 127. [Google Scholar]

- Gemiyu, D. On-Farm Performance Evaluation of Indigenous Sheep and Goats in Alaba, Southern Ethiopia. Master’s Thesis, Hawassa University, Awassa, Ethiopia, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Joy, A.; Dunshea, F.R.; Leury, B.J.; Clarke, I.J.; Digiacomo, K.; Chauhan, S.S. Resilience of Small Ruminants to Climate Change and Increased Environmental Temperature: A Review. Animals 2020, 10, 867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebbie, S.H.B. Goats under household conditions. Small Rumin. Res. 2004, 51, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. The Second Report on the State of the World’s Animal Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture Food and Agriculture Organisation, Rome 2015. Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/a-i4787e/index.html (accessed on 2 March 2023).

- Baah, J.; Tuah, A.; Addah, W.; Tait, R. Small ruminant production characteristics in urban households in Ghana. Age 2012, 29, 30–39. [Google Scholar]

- Escareño, L.; Salinas-Gonzalez, H.; Wurzinger, M.; Iñiguez, L.; Sölkner, J.; Meza-Herrera, C. Dairy goat production systems. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2012, 45, 17–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rota, A.; Urbani, I. IFAD Advantage Series: The Small Livestock Advantage: A Sustainable Entry Point for Addressing SDGs in Rural Areas; International Fund for Agricultural Development: Rome, Italy, 2021; ISBN 978-92-9266-056-7. Available online: https://www.ifad.org/fr/web/knowledge/publication/asset/42264711 (accessed on 24 January 2023).

- Molina-Flores, B.; Manzano-Baena, P.; Coulibaly, M.D. The Role of Livestock in Food Security, Poverty Reduction and Wealth Creation in West Africa; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Accra, Ghana, 2020; Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/ca8385en/CA8385EN.pdf (accessed on 8 February 2023).

- Nuvey, F.S.; Nortey, P.A.; Addo, K.K.; Addo-Lartey, A.; Kreppel, K.; Houngbedji, C.A.; Dzansi, G.; Bonfoh, B. Farm-related determinants of food insecurity among livestock dependent households in two agrarian districts with varying rainfall patterns in Ghana. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2022, 6, 743600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teshome, D.; Sori, T. Contagious caprine pleuropneumonia: A review. J. Vet. Med. Anim. Health 2021, 13, 132–143. [Google Scholar]

- Nuvey, F.S.; Arkoazi, J.; Hattendorf, J.; Mensah, G.I.; Addo, K.K.; Fink, G.; Zinsstag, J.; Bonfoh, B. Effectiveness and profitability of preventive veterinary interventions in controlling infectious diseases of ruminant livestock in sub-Saharan Africa: A scoping review. BMC Vet. Res. 2022, 18, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lhermie, G.; Pica-Ciamarra, U.; Newman, S.; Raboisson, D.; Waret-Szkuta, A. Impact of Peste des petits ruminants for sub-Saharan African farmers: A bioeconomic household production model. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2022, 69, E185–E193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leal Filho, W.; Taddese, H.; Balehegn, M.; Nzengya, D.; Debela, N.; Abayineh, A.; Mworozi, E.; Osei, S.; Ayal, D.Y.; Nagy, G.J.; et al. Introducing experiences from African pastoralist communities to cope with climate change risks, hazards and extremes: Fostering poverty reduction. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2020, 50, 101738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Livestock’s Long Shadow: Environmental Issues and Options; Food and Agriculture Organization: Rome, Italy, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Dumont, B.; Fortun-Lamothe, L.; Jouven, M.; Thomas, M.; Tichit, M. Prospects from agroecology and industrial ecology for animal production in the 21st century. Animal 2013, 7, 1028–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gliessman, S. Animals in agroecosystems. In Agroecology: The Ecology of Sustainable Food Systems, 2nd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2006; pp. 269–285. [Google Scholar]

- Dumont, B.; González-García, E.; Thomas, M.; Fortun-Lamothe, L.; Ducrot, C.; Dourmad, J.Y.; Tichit, M. Forty research issues for the redesign of animal production systems in the 21st century. Animal 2014, 8, 1382–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumont, B.; Groot, J.C.J.; Tichit, M. Review: Make ruminants green again—How can sustainable intensification and agroecology converge for a better future? Animal 2018, 12, S210–S219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wezel, A.; Bellon, S.; Doré, T.; Francis, C.; Vallod, D.; David, C. Agroecology as a science, a movement and a practice. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2009, 29, 503–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlile, R.; Garnett, T. What is Agroecology; TABLE Explainer Series; TABLE; University of Oxford; Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences; Wageningen University & Research: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- von Greyerz, K.; Tidåker, P.; Karlsson, J.O.; Röös, E. A large share of climate impacts of beef and dairy can be attributed to ecosystem services other than food production. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 325, 116400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Zanten, H.H.E.; Herrero, M.; Van Hal, O.; Röös, E.; Muller, A.; Garnett, T.; Gerber, P.J.; Schader, C.; De Boer, I.J.M. Defining a land boundary for sustainable livestock consumption. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2018, 24, 4185–4194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HLPE. Agroecological and Other Innovative Approaches for Sustainable Agriculture and Food Systems that Enhance Food Security and Nutrition. A Report by the High Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition of the Committee on World Food Security, Rome; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2019; Available online: http://www.fao.org/cfs/cfs-hlpe/en/ (accessed on 16 November 2022).

- Gliessman, S. Transforming food systems with agroecology. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 2016, 40, 187–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, G. Biogeography: Introduction to Space, Time, and Life; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, A.K. Origin of agriculture and domestication of plants and animals linked to early Holocene climate amelioration. Curr. Sci. 2004, 87, 54–59. [Google Scholar]

- Zervas, G.; Dardamani, K.; Apostolaki, H. Non-intensive dairy farming systems in Mediterranean basin: Trends and limitations. In Proceedings of the Fifth International EAAP Symposium on Livestock Farming Systems, Friburgh, Switzerland, 19–20 August 1999; pp. 107–111. [Google Scholar]

- Nalubwama, S.M.; Mugisha, A.; Vaarst, M. Organic livestock production in Uganda: Potentials, challenges and prospects. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2011, 43, 749–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- El Aich, A.; Waterhouse, A. Small ruminants in environmental conservation. Small Rumin. Res. 1999, 34, 271–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffon, M. Qu’est-ce que L’agriculture Écologiquement Intensive? Éditions Quae: Versailles, France, 2013; pp. 1–224. [Google Scholar]

- HLPE. Sustainable Agricultural Development for Food Security and Nutrition: What Roles for Livestock? A Report by the CFS; High Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition of the Committee on World Food Security: Rome, Italy, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Pretty, J.; Bharucha, Z.P. Sustainable Intensification in Agricultural Systems. Ann. Bot. 2014, 114, 1571–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resare Sahlin, K.; Carolus, J.; Von Greyerz, K.; Ekqvist, I.; Röös, E. Delivering “less but better” meat in practice—A case study of a farm in agroecological transition. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2022, 42, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wezel, A.; Herren, B.G.; Kerr, R.B.; Barrios, E.; Gonçalves, A.L.R.; Sinclair, F. Agroecological principles and elements and their implications for transitioning to sustainable food systems. A Review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 40, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. The 10 Elements of Agroecology: Guiding the Transition to Sustainable Food and Agricultural Systems; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2018; Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/i9037en/i9037en.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2023).

- Ghisellini, P.; Cialani, C.; Ulgiati, S. A review on circular economy: The expected transition to a balanced interplay of environmental and economic systems. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 114, 11–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchherr, J.; Reike, D.; Hekkert, M. Conceptualizing the circular economy: An analysis of 114 definitions. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 127, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jørgensen, S.; Pedersen, L.J.T. The Circular Rather than the Linear Economy; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 103–120. [Google Scholar]

- Franzluebbers, A.J.; Martin, G. Farming with forages can reconnect crop and livestock operations to enhance circularity and foster ecosystem services. Grass Forage Sci. 2022, 77, 270–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Zanten, H.H.E.; Van Ittersum, M.K.; De Boer, I.J.M. The role of farm animals in a circular food system. Glob. Food Secur. 2019, 21, 18–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paek, B.H.; Kang, S.W.; Cho, Y.M.; Cho, W.M.; Yang, C.J.; Yun, S.G. Effects of Substituting Concentrates with Dried Leftover Food on Growth and Carcass Characteristics of Hanwoo Steers. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2005, 18, 209–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishida, K.; Yani, S.; Kitagawa, M.; Oishi, K.; Hirooka, H.; Kumagai, H. Effects of adding food by-products mainly including noodle waste to total mixed ration silage on fermentation quality, feed intake, digestibility, nitrogen utilization and ruminal fermentation in wethers. Anim. Sci. J. 2012, 83, 735–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angulo, J.; Mahecha, L.; Yepes, S.A.; Yepes, A.M.; Bustamante, G.; Jaramillo, H.; Valencia, E.; Villamil, T.; Gallo, J. Nutritional evaluation of fruit and vegetable waste as feedstuff for diets of lactating Holstein cows. J. Environ. Manag. 2012, 95, S210–S214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shurson, G.C. “What a Waste”—Can We Improve Sustainability of Food Animal Production Systems by Recycling Food Waste Streams into Animal Feed in an Era of Health, Climate, and Economic Crises? Sustainability 2020, 12, 7071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedrich, J.; Bunker, I.; Uthes, S.; Zscheischler, J. The Potential of Bioeconomic Innovations to Contribute to a Social-Ecological Transformation: A Case Study in the Livestock System. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2021, 34, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klerkx, L.; Jakku, E.; Labarthe, P. A review of social science on digital agriculture, smart farming and agriculture 4.0: New contributions and a future research agenda. NJAS Wagening. J. Life Sci. 2019, 90–91, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bernardi, P.; Bertello, A.; Forliano, C. Circularity of food systems: A review and research agenda. Br. Food J. 2023, 125, 1094–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steenwerth, K.L.; Hodson, A.K.; Bloom, A.J.; Carter, M.R.; Cattaneo, A.; Chartres, C.J.; Hatfield, J.L.; Henry, K.; Hopmans, J.W.; Horwath, W.R.; et al. Climate-smart agriculture global research agenda: Scientific basis for action. Agric. Food Secur. 2014, 3, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, R.; Baste, I.; Larigauderie, A.; Leadley, P.; Pascual, U.; Baptiste, B.; Demissew, S.; Dziba, L.; Erpul, G.; Fazel, A. Summary for Policymakers of the Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services; IPBES Secretariat: Bonn, Germany, 2019; pp. 22–47. [Google Scholar]

- Bernués, A.; Ruiz, R.; Olaizola, A.; Villalba, D.; Casasús, I. Sustainability of pasture-based livestock farming systems in the European Mediterranean context: Synergies and trade-offs. Livest. Sci. 2011, 139, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tompkins, E.L.; Adger, W.N. Does Adaptive Management of Natural Resources Enhance Resilience to Climate Change? Ecol. Soc. 2004, 9, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baiyeri, P.K.; Foleng, H.N.; Machebe, N.S.; Nwobodo, C.E. Crop-Livestock Interaction for Sustainable Agriculture. In Innovations in Sustainable Agriculture; Farooq, M., Pisante, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 557–582. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, L.S.; Laroca, J.V.d.S.; Coelho, A.P.; Gonçalves, E.C.; Gomes, R.P.; Pacheco, L.P.; Carvalho, P.C.d.F.; Pires, G.C.; Oliveira, R.L.; Souza, J.M.A.d.; et al. Does grass-legume intercropping change soil quality and grain yield in integrated crop-livestock systems? Appl. Soil Ecol. 2022, 170, 104257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paramesh, V.; Ravisankar, N.; Behera, U.; Arunachalam, V.; Kumar, P.; Solomon Rajkumar, R.; Dhar Misra, S.; Mohan Kumar, R.; Prusty, A.K.; Jacob, D.; et al. Integrated farming system approaches to achieve food and nutritional security for enhancing profitability, employment, and climate resilience in India. Food Energy Secur. 2022, 11, e321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teague, R.; Provenza, F.; Kreuter, U.; Steffens, T.; Barnes, M. Multi-paddock grazing on rangelands: Why the perceptual dichotomy between research results and rancher experience? J. Environ. Manag. 2013, 128, 699–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Jin, H.; Kreuter, U.; Teague, R. Understanding producers’ perspectives on rotational grazing benefits across US Great Plains. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2022, 37, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- di Virgilio, A.; Lambertucci, S.A.; Morales, J.M. Sustainable grazing management in rangelands: Over a century searching for a silver bullet. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2019, 283, 106561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Provenza, F.; Pringle, H.; Revell, D.; Bray, N.; Hines, C.; Teague, R.; Steffens, T.; Barnes, M. Complex Creative Systems. Rangelands 2013, 35, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosati, A.; Borek, R.; Canali, S. Agroforestry and organic agriculture. Agrofor. Syst. 2021, 95, 805–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charles, R.L.; Munishi, P.; Nzunda, E.F. Agroforestry as adaptation strategy under climate change in Mwanga District, Kilimanjaro, Tanzania. Int. J. Environ. Prot. 2013, 3, 29–38. [Google Scholar]

- Latawiec, A.E.; Strassburg, B.B.N.; Valentim, J.F.; Ramos, F.; Alves-Pinto, H.N. Intensification of cattle ranching production systems: Socioeconomic and environmental synergies and risks in Brazil. Animal 2014, 8, 1255–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassie, M.; Stage, J.; Diiro, G.; Muriithi, B.; Muricho, G.; Ledermann, S.T.; Pittchar, J.; Midega, C.; Khan, Z. Push–pull farming system in Kenya: Implications for economic and social welfare. Land Use Policy 2018, 77, 186–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Midega, C.A.O.; Pittchar, J.O.; Pickett, J.A.; Hailu, G.W.; Khan, Z.R. A climate-adapted push-pull system effectively controls fall armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda (J E Smith), in maize in East Africa. Crop Prot. 2018, 105, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chepchirchir, R.T.; Macharia, I.; Murage, A.W.; Midega, C.A.O.; Khan, Z.R. Impact assessment of push-pull pest management on incomes, productivity and poverty among smallholder households in Eastern Uganda. Food Secur. 2017, 9, 1359–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndayisaba, P.C.; Kuyah, S.; Midega, C.A.O.; Mwangi, P.N.; Khan, Z.R. Push-pull technology improves maize grain yield and total aboveground biomass in maize-based systems in Western Kenya. Field Crops Res. 2020, 256, 107911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gugissa, D.A.; Abro, Z.; Tefera, T. Achieving a Climate-Change Resilient Farming System through Push&Pull Technology: Evidence from Maize Farming Systems in Ethiopia. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murage, A.W.; Midega, C.A.O.; Pittchar, J.O.; Pickett, J.A.; Khan, Z.R. Determinants of adoption of climate-smart push-pull technology for enhanced food security through integrated pest management in eastern Africa. Food Secur. 2015, 7, 709–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kebede, Y.; Baudron, F.; Bianchi, F.; Tittonell, P. Unpacking the push-pull system: Assessing the contribution of companion crops along a gradient of landscape complexity. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2018, 268, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muriithi, B.W.; Menale, K.; Diiro, G.; Muricho, G. Does gender matter in the adoption of push-pull pest management and other sustainable agricultural practices? Evidence from Western Kenya. Food Secur. 2018, 10, 253–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niassy, S.; Agbodzavu, M.K.; Mudereri, B.T.; Kamalongo, D.; Ligowe, I.; Hailu, G.; Kimathi, E.; Jere, Z.; Ochatum, N.; Pittchar, J.; et al. Performance of Push&Pull Technology in Low-Fertility Soils under Conventional and Conservation Agriculture Farming Systems in Malawi. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayoola, O.T.; Adeniyan, O.N. Influence of poultry manure and NPK fertilizer on yield and yield components of crops under different cropping systems in south west Nigeria. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2006, 5, 1386–1392. [Google Scholar]

- Motsi, T.; Kugedera, A.; Kokerai, L. Role of cattle manure and inorganic fertilizers in improving maize productivity in semi-arid areas of Zimbabwe. Oct. Jour. Environ. Res. 2019, 7, 122–129. [Google Scholar]

- Ka, S.L.; Gueye, M.; Mbaye, M.S.; Kanfany, G.; Noba, K. Response of a weed community to organic and inorganic fertilization in peanut crop under Savannah zone of Senegal, West Africa. J. Res. Weed Sci. 2019, 2, 241–252. [Google Scholar]

- Gezahegn, A.M. Role of Integrated Nutrient Management for Sustainable Maize Production. Int. J. Agron. 2021, 2021, 9982884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhereza, I.; Prichard, D.; Murray-Prior, R. Utilisation of cattle manure and inorganic fertiliser for food production in central Uganda. J. Agric. Environ. Int. Dev. 2014, 108, 135–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makinde, E.; Ayoola, O. Maize growth, yield and soil nutrient changes with N-enriched organic fertilizers. Afr. J. Food Agric. Nutr. Dev. 2009, 9, 581–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulraheem, M.I.; Lawal, S.A. Combined application of ammonium nitrate and goat manure: Effects on soil nutrients availability, Okra performance and sustainable food security. Open Access Res. J. Life Sci. 2021, 1, 021–028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balemi, T. Effect of integrated use of cattle manure and inorganic fertilizers on tuber yield of potato in Ethiopia. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2012, 12, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katuromunda, S.; Sabiiti, E.; Bekunda, M. Effect of combined application of cattle manure and mineral fertilisers on the growth characteristics and quality of Pennisetum purpureum fodder. Livest. Res. Rural Dev. 2011, 23, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Ndung’u, M.; Ngatia, L.; Onwonga, R.; Mucheru-Muna, M.; Fu, R.; Moriasi, D.; Ngetich, K. The influence of organic and inorganic nutrient inputs on soil organic carbon functional groups content and maize yields. Heliyon 2021, 7, e07881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macharia, J.M.; Pelster, D.E.; Ngetich, F.K.; Shisanya, C.A.; Mucheru-Muna, M.; Mugendi, D.N. Soil Greenhouse Gas Fluxes From Maize Production Under Different Soil Fertility Management Practices in East Africa. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosciences 2020, 125, e2019JG005427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sileshi Gudeta, W.; Bashir, J.; Vanlauwe, B.; Negassa, W.; Rebbie, H.; Abednego, K.; Kimani, D. Nutrient use efficiency and crop yield response to the combined application of cattle manure and inorganic fertilizer in sub-Saharan Africa. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosyst. 2019, 113, 181–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemal, Y.O.; Abera, M. Contribution of integrated nutrient management practices for sustainable crop productivity, nutrient uptake and soil nutrient status in maize based cropping systems. J. Nutr. 2015, 2, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd El-Gawad, A.; Morsy, A. Integrated Impact of Organic and Inorganic Fertilizers on Growth, Yield of Maize (Zea mays L.) and Soil Properties under Upper Egypt Conditions. J. Plant Prod. 2017, 8, 1103–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuralkar, P.; Kuralkar, S.V. Role of herbal products in animal production—An updated review. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2021, 278, 114246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikelo, W.; Mpayipheli, M.; McGaw, L. Managing Internal Parasites of Small Ruminants using Medicinal Plants a Review on Alternative Remedies, Efficacy Evaluation Techniques and Conservational Strategies. Am. J. Anim. Vet. Sci. 2022, 17, 228–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, L.; Yu, J.; Hartanto, R.; Qi, D. Dietary Supplementation with Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Clostridium butyricum and Their Combination Ameliorate Rumen Fermentation and Growth Performance of Heat-Stressed Goats. Animals 2021, 11, 2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, N.A.; Chethan, H.S.; Srivastava, R.; Gabbur, A.B. Role of probiotics in ruminant nutrition as natural modulators of health and productivity of animals in tropical countries: An overview. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2022, 54, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adjei-Fremah, S.; Ekwemalor, K.; Worku, M.; Ibrahim, S. Probiotics and ruminant health. In Probiotics—Current Knowledge and Future Prospects; InTech: London, UK, 2018; pp. 133–150. [Google Scholar]

- Cabaret, J. Practical recommendations on the control of helminth parasites in organic sheep production systems. CABI Rev. 2007, 2007, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidane, A.; Houdijk, J.G.M.; Athanasiadou, S.; Tolkamp, B.J.; Kyriazakis, I. Effects of maternal protein nutrition and subsequent grazing on chicory (Cichorium intybus) on parasitism and performance of lambs1. J. Anim. Sci. 2010, 88, 1513–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marie-Magdeleine, C.; Mahieu, M.; Philibert, L.; Despois, P.; Archimède, H. Effect of cassava (Manihot esculenta) foliage on nutrition, parasite infection and growth of lambs. Small Rumin. Res. 2010, 93, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villalba, J.J.; Provenza, F.D.; Shaw, R. Sheep self-medicate when challenged with illness-inducing foods. Anim. Behav. 2006, 71, 1131–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gradé, J.T.; Tabuti, J.R.S.; Van Damme, P. Four Footed Pharmacists: Indications of Self-Medicating Livestock in Karamoja, Uganda. Econ. Bot. 2009, 63, 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silanikove, N. The physiological basis of adaptation in goats to harsh environments. Small Rumin. Res. 2000, 35, 181–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, A. Invited review: Are adaptations present to support dairy cattle productivity in warm climates? J. Dairy Sci. 2011, 94, 2147–2158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandonnet, N.; Tillard, E.; Faye, B.; Collin, A.; Gourdine, J.L.; Naves, M.; Bastianelli, D.; Tixier-Boichard, M.; Renaudeau, D. Adaptation des animaux d’élevage aux multiples contraintes des régions chaudes. INRAE Prod. Anim. 2011, 24, 41–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sechi, S.; Salaris, S.; Scala, A.; Rupp, R.; Moreno, C.; Bishop, S.; Casu, S. Estimation of (co)variance components of nematode parasites resistance and somatic cell count in dairy sheep. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2009, 8, 156–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. One Health. 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/one-health#tab=tab_1 (accessed on 21 June 2023).

- Mahieu, M. Effects of stocking rates on gastrointestinal nematode infection levels in a goat/cattle rotational stocking system. Vet. Parasitol. 2013, 198, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, G.; Barth, K.; Benoit, M.; Brock, C.; Destruel, M.; Dumont, B.; Grillot, M.; Hübner, S.; Magne, M.-A.; Moerman, M.; et al. Potential of multi-species livestock farming to improve the sustainability of livestock farms: A review. Agric. Syst. 2020, 181, 102821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kara, K.; Özkaya, S.; Erbaş, S.; Baytok, E. Effect of dietary formic acid on the in vitro ruminal fermentation parameters of barley-based concentrated mix feed of beef cattle. J. Appl. Anim. Res. 2018, 46, 178–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palangi, V.; Macit, M. Indictable Mitigation of Methane Emission Using Some Organic Acids as Additives Towards a Cleaner Ecosystem. Waste Biomass Valorization 2021, 12, 4825–4834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Githiori, J.B.; HÖglund, J.; Waller, P.J.; Baker, R.L. Evaluation of anthelmintic properties of some plants used as livestock dewormers against Haemonchus contortus infections in sheep. Parasitology 2004, 129, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mkhize, N.R.; Heitkönig, I.M.A.; Scogings, P.F.; Dziba, L.E.; Prins, H.H.T.; de Boer, W.F. Effects of condensed tannins on live weight, faecal nitrogen and blood metabolites of free-ranging female goats in a semi-arid African savanna. Small Rumin. Res. 2018, 166, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elaref, M.Y.; Hamdon, H.A.M.; Nayel, U.A.; Salem, A.Z.M.; Anele, U.Y. Influence of dietary supplementation of yeast on milk composition and lactation curve behavior of Sohagi ewes, and the growth performance of their newborn lambs. Small Rumin. Res. 2020, 191, 106176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ban, Y.; Guan, L.L. Implication and challenges of direct-fed microbial supplementation to improve ruminant production and health. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2021, 12, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, A.; Osafo, E.L.K.; Attoh-Kotoku, V.; Yunus, A.A. Effects of supplementing probiotics and concentrate on intake, growth performance and blood profile of intensively kept Sahelian does fed a basal diet of Brachiaria decumbens grass. J. Appl. Anim. Res. 2023, 51, 414–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maake, T.W.; Adeleke, M.; Aiyegoro, O.A. Effect of lactic acid bacteria administered as feed supplement on the weight gain and ruminal pH in two South African goat breeds. Trans. R. Soc. South Afr. 2021, 76, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mani, S.; Aiyegoro, O.A.; Adeleke, M.A. Characterization of Rumen Microbiota of Two Sheep Breeds Supplemented With Direct-Fed Lactic Acid Bacteria. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 7, 570074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunus, A.A. Effect of Probiotic (RE3) supplement on growth performance, diarrhea incidence and blood parameters of N’dama calves. J. Prob. Health 2017, 6, 62. [Google Scholar]

- Bonaudo, T.; Bendahan, A.B.; Sabatier, R.; Ryschawy, J.; Bellon, S.; Leger, F.; Magda, D.; Tichit, M. Agroecological principles for the redesign of integrated crop–livestock systems. Eur. J. Agron. 2014, 57, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jose, S. Agroforestry for conserving and enhancing biodiversity. Agrofor. Syst. 2012, 85, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elevitch, C.; Mazaroli, D.; Ragone, D. Agroforestry Standards for Regenerative Agriculture. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USDA. USDA Agroforestry Strategic Framework, Fiscal Year 2011–2016; U.S. Department of Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA, 2011.

- McNeely, J.A.; Schroth, G. Agroforestry and Biodiversity Conservation—Traditional Practices, Present Dynamics, and Lessons for the Future. Biodivers. Conserv. 2006, 15, 549–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeely, J.A. Nature vs. nurture: Managing relationships between forests, agroforestry and wild biodiversity. Agrofor. Syst. 2004, 61, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jose, S. Agroforestry for ecosystem services and environmental benefits: An overview. Agrofor. Syst. 2009, 76, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, C.A.; Gonzalez, J.; Somarriba, E. Dung Beetle and Terrestrial Mammal Diversity in Forests, Indigenous Agroforestry Systems and Plantain Monocultures in Talamanca, Costa Rica. Biodivers. Conserv. 2006, 15, 555–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teague, R.; Kreuter, U. Managing Grazing to Restore Soil Health, Ecosystem Function, and Ecosystem Services. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2020, 4, 534187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, K.M.; Gaudin, A.C.M. Potential of crop-livestock integration to enhance carbon sequestration and agroecosystem functioning in semi-arid croplands. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2020, 149, 107936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Zhang, W.; Li, L. Intercropping: Feed more people and build more sustainable agroecosystems. Front. Agric. Sci. Eng. 2021, 8, 373–386. [Google Scholar]

- Villalba, J.J.; Provenza, F.D.; Catanese, F.; Distel, R.A. Understanding and manipulating diet choice in grazing animals. Anim. Prod. Sci. 2015, 55, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Distel, R.A.; Arroquy, J.I.; Lagrange, S.; Villalba, J.J. Designing Diverse Agricultural Pastures for Improving Ruminant Production Systems. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2020, 4, 596869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagrange, S.; Villalba, J.J. Tannin-containing legumes and forage diversity influence foraging behavior, diet digestibility, and nitrogen excretion by lambs1,2. J. Anim. Sci. 2019, 97, 3994–4009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altieri, M.A.; Nicholls, C.I. Agroecology: Challenges and opportunities for farming in the Anthropocene. Cienc. Investig. Agrar. Rev. Latinoam. Cienc. Agric. 2020, 47, 204–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godfray, H.C.J.; Beddington, J.R.; Crute, I.R.; Haddad, L.; Lawrence, D.; Muir, J.F.; Pretty, J.; Robinson, S.; Thomas, S.M.; Toulmin, C. Food Security: The Challenge of Feeding 9 Billion People. Science 2010, 327, 812–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrero, M.; Thornton, P.K.; Notenbaert, A.M.; Wood, S.; Msangi, S.; Freeman, H.A.; Bossio, D.; Dixon, J.; Peters, M.; van de Steeg, J.; et al. Smart Investments in Sustainable Food Production: Revisiting Mixed Crop-Livestock Systems. Science 2010, 327, 822–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assing, A.C.B.B. Agroecology: A Proposal for Livelihood, Ecosystem Services Provision and Biodiversity Conservation for Small Dairy Farms in Santa Catarina. Ph.D. Thesis, University of São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil, 29 March 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabral, J.P.; Faria, D.; Morante-Filho, J.C. Landscape composition is more important than local vegetation structure for understory birds in cocoa agroforestry systems. For. Ecol. Manag. 2021, 481, 118704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scohier, A.; Ouin, A.; Farruggia, A.; Dumont, B. Is there a benefit of excluding sheep from pastures at flowering peak on flower-visiting insect diversity? J. Insect Conserv. 2013, 17, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinfeld, H.; Wassenaar, T. The Role of Livestock Production in Carbon and Nitrogen Cycles. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2007, 32, 271–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, L.E.; Pascual, U.; Hodgkin, T. Utilizing and conserving agrobiodiversity in agricultural landscapes. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2007, 121, 196–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duru, M.; Therond, O.; Martin, G.; Martin-Clouaire, R.; Magne, M.-A.; Justes, E.; Journet, E.-P.; Aubertot, J.-N.; Savary, S.; Bergez, J.-E.; et al. How to implement biodiversity-based agriculture to enhance ecosystem services: A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2015, 35, 1259–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brussaard, L.; Caron, P.; Campbell, B.; Lipper, L.; Mainka, S.; Rabbinge, R.; Babin, D.; Pulleman, M. Reconciling biodiversity conservation and food security: Scientific challenges for a new agriculture. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2010, 2, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Livestock and Agroecology (pp. 16). 2018. Available online: https://www.fao.org/publications/card/fr/c/I8926EN/ (accessed on 10 February 2023).

- FAO. Recycling: More Recycling Means Agricultural Production with Lower Economic and Environmental Costs. 2023. Available online: https://www.fao.org/agroecology/knowledge/10-elements/recycling/en/ (accessed on 10 February 2023).

- Boudra, H.; Rouillé, B.; Lyan, B.; Morgavi, D.P. Presence of mycotoxins in sugar beet pulp silage collected in France. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2015, 205, 131–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammann, A.; Ybañez, L.M.; Isla, M.I.; Hilal, M.B. Potential agricultural use of a sub product (olive cake) from olive oil industries composting with soil. J. Pharm. Pharmacogn. Res. 2019, 8, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navarro, S.; Vela, N. Fate of Pesticide Residues during Brewing. In Beer in Health and Disease Prevention; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2009; pp. 415–428. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.-I.; Cho, E.-J.; Lyonga, F.N.; Lee, C.-H.; Hwang, S.-Y.; Kim, D.-H.; Lee, C.-G.; Park, S.-J. Thermo-chemical treatment for carcass disposal and the application of treated carcass as compost. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gooding, C.H.; Meeker, D.L. Comparison of 3 alternatives for large-scale processing of animal carcasses and meat by-products. Prof. Anim. Sci. 2016, 32, 259–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gale, P. Risks to farm animals from pathogens in composted catering waste containing meat. Vet. Rec. 2004, 155, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, G. The foot and mouth disease (FMD) epidemic in the United Kingdom 2001. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2002, 25, 331–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terpstra, C.; Wensvoort, G. African swine fever in the Netherlands. Tijdschr. Voor Diergeneeskd. 1986, 111, 389–392. [Google Scholar]

- Akram, M.Z.; Firincioğlu, S.Y. The Use of Agricultural Crop Residues as Alternatives to Conventional Feedstuffs for Ruminants: A Review. Eurasian J. Agric. Res. 2019, 3, 58–66. [Google Scholar]

- Jansen, L.J.; Bolck, Y.J.; Rademaker, J.; Zuidema, T.; Berendsen, B.J. The analysis of tetracyclines, quinolones, macrolides, lincosamides, pleuromutilins, and sulfonamides in chicken feathers using UHPLC-MS/MS in order to monitor antibiotic use in the poultry sector. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2017, 409, 4927–4941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumont, B.; Puillet, L.; Martin, G.; Savietto, D.; Aubin, J.; Ingrand, S.; Niderkorn, V.; Steinmetz, L.; Thomas, M. Incorporating Diversity Into Animal Production Systems Can Increase Their Performance and Strengthen Their Resilience. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2020, 4, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stratton, A.E.; Wittman, H.; Blesh, J. Diversification supports farm income and improved working conditions during agroecological transitions in southern Brazil. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 41, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gliessman, S. The co-creation of agroecological knowledge. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 2018, 42, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utter, A.; White, A.; Ernesto, M.V.; Morris, K. Co-creation of knowledge in agroecology. Elem. Sci. Anthr. 2021, 9, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuéllar-Padilla, M.; Calle-Collado, Á. Can we find solutions with people? Participatory action research with small organic producers in Andalusia. J. Rural Stud. 2011, 27, 372–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, K.D. Agroecology as participatory science: Emerging alternatives to technology transfer extension practice. Sci. Technol. Hum. Values 2008, 33, 754–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charatsari, C.; Lioutas, E.D.; Koutsouris, A. Farmer Field Schools and the Co-Creation of Knowledge and Innovation: The Mediating Role of Social Capital. In Social Innovation and Sustainability Transition; Desa, G., Jia, X., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 205–220. [Google Scholar]

- Rivera, A. Advancing Agroecology through Knowledge Co-Creation: Exploring Success Conditions to Enhance the Adoption of Agroecological Farming Practices, Illustrated by the Case of Chilean Wineries. Master’s Thesis, Utrecht University, Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Triste, L.; Debruyne, L.; Vandenabeele, J.; Marchand, F.; Lauwers, L. Communities of practice for knowledge co-creation on sustainable dairy farming: Features for value creation for farmers. Sustain. Sci. 2018, 13, 1427–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello Cartagena, L. Bridging the Gap between Theory and Practice in Agro-Ecological Farming: Analyzing Knowledge Co-Creation among Farmers and Scientific Researchers in Southern Spain. Master’s Thesis, Utrecht University, Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Larsen, A.F.; Lilleør, H.B. Beyond the Field: The Impact of Farmer Field Schools on Food Security and Poverty Alleviation. World Dev. 2014, 64, 843–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis-Jones, J.; Schulz, S.; Chikoye, D.; de Haan, N.; Kormawa, P.; Adedzwa, D. Participatory Research and Extension Approaches; IITA: Ibadan, Nigeria, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Méndez, V.; Caswell, M.; Gliessman, S.; Cohen, R. Integrating Agroecology and Participatory Action Research (PAR): Lessons from Central America. Sustainability 2017, 9, 705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, J. Lessons from action-research partnerships: LASA/Oxfam America 2004 Martin Diskin Memorial Lecture. Dev. Pract. 2006, 16, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, R.; Ghildyal, B.P. Agricultural research for resource-poor farmers: The farmer-first-and-last model. Agric. Adm. 1985, 20, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, R.; Ampt, P. Exploring Agroecological Sustainability: Unearthing Innovators and Documenting a Community of Practice in Southeast Australia. Soc. Amp; Nat. Resour. 2017, 30, 585–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heleba, D.; Darby, H.; Grubinger, V.; Méndez, V.; Bacon, C.; Cohen, R.; Gliessman, S. On the Ground: Putting Agroecology to Work through Extension Research and Outreach in Vermont. Agroecology: A Transdisciplinary, Participatory and Actionoriented Approach; Invited Book for the Advances in Agroecology Series; CRC Press/Taylor & Francis: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Johansson, E.L. Participatory futures thinking in the African context of sustainability challenges and socio-environmental change. Ecol. Soc. 2021, 26, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altieri, M.A.; Nicholls, C.I. Agroecology Scaling Up for Food Sovereignty and Resiliency; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Altieri, M.A.; Funes-Monzote, F.R.; Petersen, P. Agroecologically efficient agricultural systems for smallholder farmers: Contributions to food sovereignty. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2012, 32, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altieri, M.A.; Toledo, V.M. The agroecological revolution in Latin America: Rescuing nature, ensuring food sovereignty and empowering peasants. J. Peasant Stud. 2011, 38, 587–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desmarais, A.A. The via campesina: Peasant women at the frontiers of food sovereignty. Can. Woman Stud. 2003, 23, 140–145. [Google Scholar]

- Rosset, P. Food sovereignty. Via Campesina 2003, 9, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Carlile, R.; Kessler, M.; Garnett, T. What is Food Sovereignty? TABLE Explainer Series; TABLE; University of Oxford; Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences; Wageningen University & Research: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Coulson, H.; Milbourne, P. Food justice for all?: Searching for the ‘justice multiple’ in UK food movements. Agric. Hum. Values 2021, 38, 43–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkon, A.H.; Agyeman, J. Cultivating Food Justice: Race, Class, and Sustainability; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

| Potential Risks | Explanation | References |

|---|---|---|

| Contaminants and toxins | Recycled feed from unknown sources may contain contaminants, pesticides, heavy metals, or toxins that could negatively impact animal health. | [145,146,147,148,149] |

| Disease transmission | Feeding recycled materials from unknown sources can introduce infectious diseases and pathogens into a herd or flock, leading to disease outbreaks. | [150,151,152] |

| Imbalanced nutritional composition | The nutritional content of recycled feed may not be well-balanced, lacking essential nutrients or having an inappropriate nutrient ratio for livestock. | [153] |

| Spread of antimicrobial resistance | Feeding recycled materials can contribute to the spread of antimicrobial resistance, making infections harder to treat in both animals and humans. | [154] |

| Gliessman’s Level | Related Principle | Practical Examples | Integration into African Food Systems | Ecological Production Techniques and Opportunities | Benefits | Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level 1: Practices that increase efficiency | Input reduction | Using local feed sources and reducing reliance on imported feed Reducing the use of chemical fertilizers and pesticides Limiting the use of antibiotics and growth hormones in animal feed Using drought-tolerant forages and pasture management to minimize the use of water and chemical fertilizers | Promoting the use of locally available feed resources, such as crop residues and forage Encouraging farmers to adopt integrated pest management techniques Providing education and training to farmers on the use of natural fertilizers Promoting the use of low-input production systems and developing policies that support input reduction | Agroforestry Rotational grazing Crop–livestock integration | Reduced cost of production Reduced environmental impact Healthier animals Increased resilience to climate change | Limited access to alternative inputs Lack of knowledge and skills to optimize the use of available resources Resistance to transition from conventional practices Limited availability of low-input technologies and knowledge gaps among farmers |

| Level 2: Substitution of agroecological inputs and practices | Animal health | Using natural remedies and biocontrol agents to treat and prevent disease | Encouraging farmers to adopt natural remedies and supplements Providing education and training on the use of probiotics Conducting research for the creation of evidence of use | Herbal medicine, probiotics, and biocontrol agents | Reduced cost of animal health management Reduced reliance on synthetic inputs | Limited availability of natural remedies Lack of knowledge, skills, and scientific evidence to use natural remedies effectively Limited knowledge of the sustainability of raw materials |

| Level 3: Redesigning agroecosystems | Synergy, recycling, soil health, preserving biodiversity | Implementing integrated crop–livestock systems and agroforestry Intercropping with legumes to fix nitrogen in the soil Incorporating crop residues into animal feed Composting animal manure and crop residues for use as natural fertilizer Advocacy and policy reform to promote agroecology and biodiversity conservation Encouraging the use of indigenous breeds of small ruminants | Promoting integrated crop–livestock systems and agroforestry to promote ecological processes Encouraging farmers to adopt intercropping practices Providing education and training on crop residue management Promoting the use of composting techniques Promoting the development and implementation of policies that support agroecology and biodiversity conservation Establishing breeding programs for indigenous small ruminant breeds | Agroforestry, integrated crop–livestock systems, conservation agriculture Advocacy and policy reform, participatory governance, ecological intensification | Improved soil fertility, increased biodiversity, reduced environmental impact, improved resilience to climate change Reduced costs Improved animal nutrition Improved environmental sustainability, increased biodiversity, improved livelihoods for smallholder farmers | Lack of knowledge and skills to implement integrated systems, limited access to diverse genetic resources Limited knowledge and understanding of intercropping practices Limited access to appropriate crop residues Limited knowledge and understanding of composting techniques Limited political will and commitment, competing interests and priorities Limited access to breeding programs for indigenous small ruminant breeds Limited interaction within the small ruminant holder value chain stakeholders |

| Level 4: Re-connection between producers and consumers | Economic diversification, cocreation of knowledge | Raising many species in a pastoral system Sale of animal byproducts Direct marketing Encouraging farmer participation in research and development Facilitating farmer-to-farmer knowledge sharing Developing local markets and value chains Farmer field schools (FFSs) bringing together small ruminant farmers to share knowledge and experiences Participatory research and extension approaches (PREAs) involving farmers in research activities to cocreate knowledge Creation of agroecology networks to connect small ruminant producers with researchers, extension officers, and other stakeholders to facilitate the cocreation of knowledge | Promoting the local animal industry Strengthening small ruminant industry chains and farmer–consumer connections Engaging farmers in research and development projects Providing platforms for farmer-to-farmer knowledge sharing Promoting the development of local markets and value chains through participatory processes Providing support to existing farmer networks in Africa and creating new ones to facilitate knowledge cocreation and sharing Supporting participatory research and extension approaches that involve farmers in the development and dissemination of agroecological practices Developing policies that support knowledge cocreation and sharing between different stakeholders in the food system | Additional income, product diversification, and market expansion Encouraging farmers’ markets Participatory research, participatory value chain development Community-supported agriculture | Risk mitigation Increased resilience Multiple strains of income Improved knowledge and understanding of sustainable agricultural practices Increased adoption of sustainable practices Improved access to markets, increased income for smallholder farmers Improved food security for local communities Improved small ruminant production through knowledge cocreation and sharing Increased farmer participation and ownership in agroecological transitions Enhanced livelihoods for small ruminant producers through increased productivity and profitability | Limited resources for research and development Limited access to information and communication technologies Limited infrastructure and access to markets, limited access to financial resources Limited access to knowledge and information among small ruminant farmers in LMICs Limited resources and infrastructure for supporting knowledge cocreation and sharing Limited policy support for the cocreation of knowledge and participation of small ruminant producers in agroecological transitions |

| Level 5: Global reform | Cocreation of knowledge | The Via Campesina food sovereignty Food Justice Movement Slow Food movement Alliance for Food Sovereignty in Africa (AFSA) Comprehensive Africa Agriculture Development Program (CAADP) International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD)—Enhanced Smallholder Agribusiness Promotion Program (E-SAPP) Global Alliance for Climate-Smart Agriculture (GACSA) | Advocating for policies and practices that support agroecology and food sovereignty Promoting community-based approaches to small ruminant production Emphasizing the importance of small-scale producers Prioritizing sustainable, community-based approaches to small ruminant production | Promoting ecological and social sustainability of small ruminant production systems | Creating a more sustainable and equitable food system Benefitting small ruminant producers, consumers, and the environment Supporting small-scale producers | Implementing the fundamental transformation of the entire food system Addressing the root causes of hunger and poverty Requires systemic changes in policies and institutions Resistance from large-scale industrial producers |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Anim-Jnr, A.S.; Sasu, P.; Bosch, C.; Mabiki, F.P.; Frimpong, Y.O.; Emmambux, M.N.; Greathead, H.M.R. Sustainable Small Ruminant Production in Low- and Middle-Income African Countries: Harnessing the Potential of Agroecology. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15326. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152115326

Anim-Jnr AS, Sasu P, Bosch C, Mabiki FP, Frimpong YO, Emmambux MN, Greathead HMR. Sustainable Small Ruminant Production in Low- and Middle-Income African Countries: Harnessing the Potential of Agroecology. Sustainability. 2023; 15(21):15326. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152115326

Chicago/Turabian StyleAnim-Jnr, Antoinette Simpah, Prince Sasu, Christine Bosch, Faith Philemon Mabiki, Yaw Oppong Frimpong, Mohammad Naushad Emmambux, and Henry Michael Rivers Greathead. 2023. "Sustainable Small Ruminant Production in Low- and Middle-Income African Countries: Harnessing the Potential of Agroecology" Sustainability 15, no. 21: 15326. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152115326

APA StyleAnim-Jnr, A. S., Sasu, P., Bosch, C., Mabiki, F. P., Frimpong, Y. O., Emmambux, M. N., & Greathead, H. M. R. (2023). Sustainable Small Ruminant Production in Low- and Middle-Income African Countries: Harnessing the Potential of Agroecology. Sustainability, 15(21), 15326. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152115326