The Impact of Customer Incivility and Its Consequences on Hotel Employees: Mediating Role of Employees’ Emotional Exhaustion

Abstract

:1. Introduction

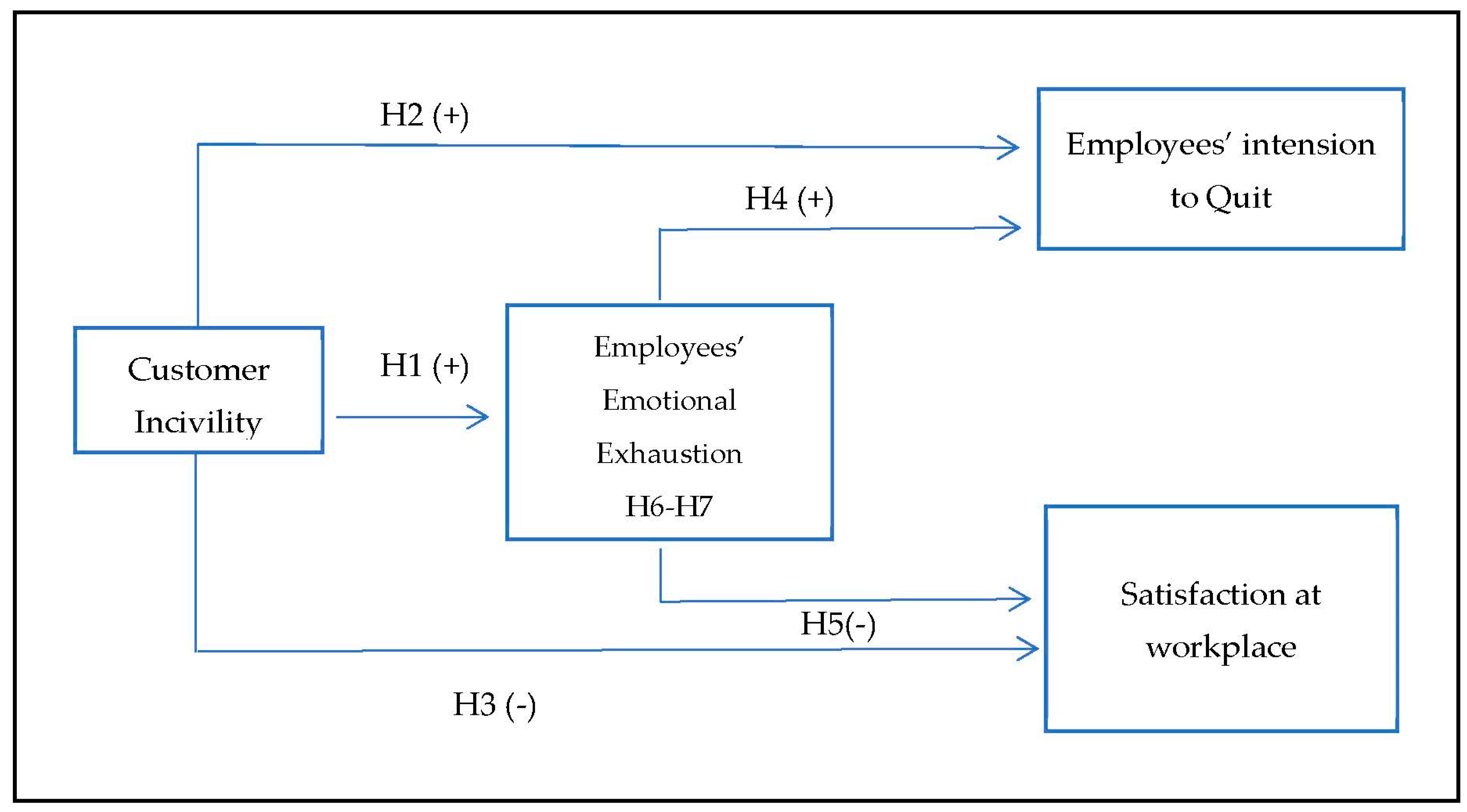

2. Background Theory and Assumptions Formation

3. Employees’ Emotional Exhaustion, Incivility, Employee Intention to Quit the Workplace, and Work Satisfaction

3.1. Employees’ Emotional Exhaustion, Employee Work Satisfaction, and Intentions to Quit the Workplace

3.2. Employees’ Emotional Exhaustion Act as a Mediator

4. Methodology of Investigation

4.1. Procedures and Sampling

4.2. Methods for Measurement

4.2.1. Customer Incivility

4.2.2. Employees’ Emotional Exhaustion

4.2.3. Employees’ Intention to Quit the Workplace

4.2.4. Employees’ Satisfaction at Workplace

4.3. Analyze the Data

5. Results

5.1. Measures’ Psychometric Qualities

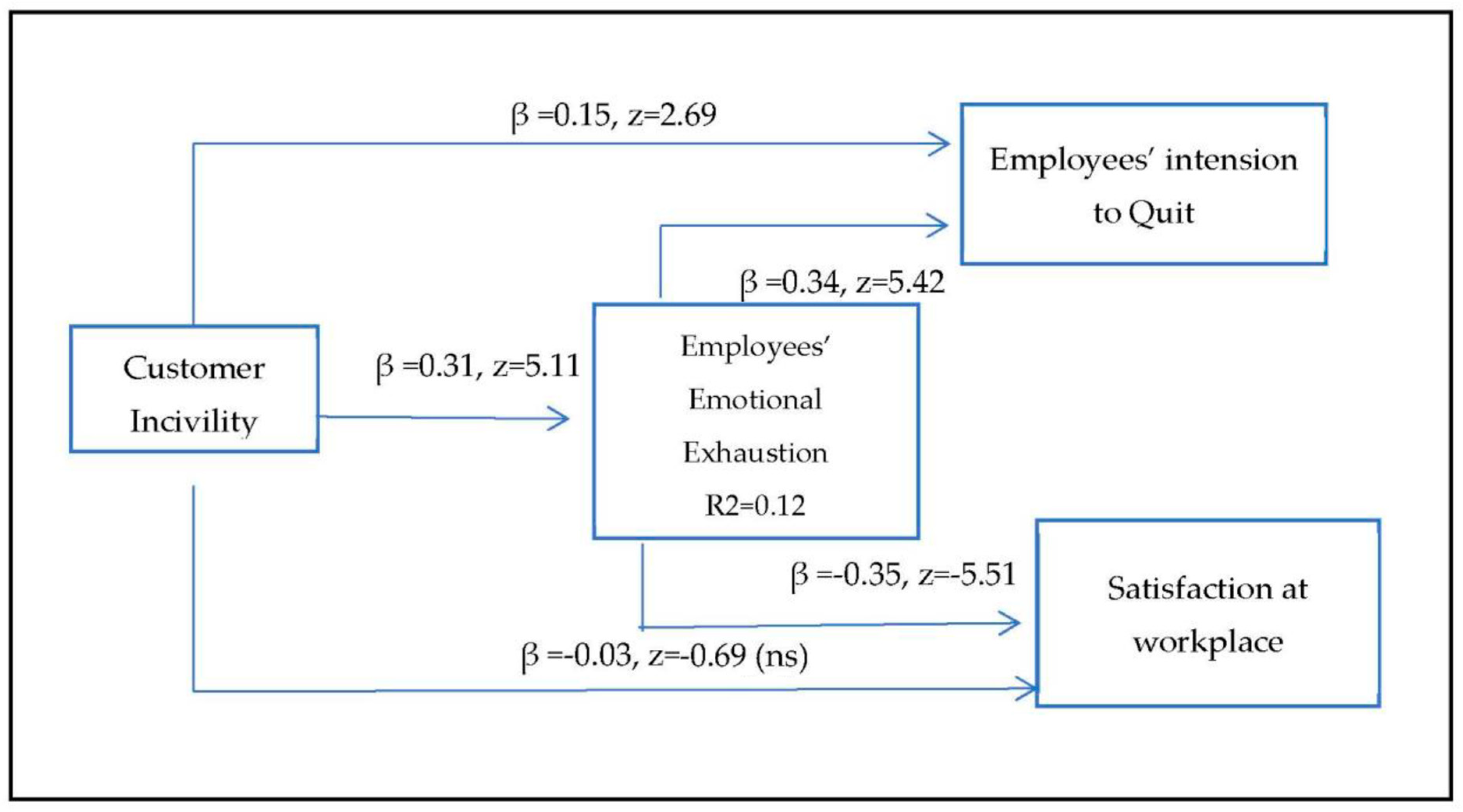

5.2. Hypothesized Model Tests

6. Conclusions

6.1. Implications for Theory

6.2. Practical Implications

6.3. Future Directions and Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zopiatis, A.; Constanti, P.; Theocharous, A.L. Job involvement, commitment, satisfaction and turnover: Evidence from hotel employees in Cyprus. Tour. Manag. 2014, 41, 129–140. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.F.; Kao, Y.L. Investigating the antecedents and consequences of burnout and isolation among flight attendants. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 868–874. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X.; Ma, J.; Dong, X. Empowering supervision and service sabotage: A moderated mediation model based on conservation of resources theory. Tour. Manag. 2018, 64, 170–187. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, S.; Shahzad, F.; Hussain, I.; Yongjian, P.; Khan, M.M.; Iqbal, Z. The Outcomes of Organizational Cronyism: A Social Exchange Theory Perspective. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 805262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, Y.D.; Chen, K.Y.; Zhuang, W.L. Moderating effect of work–family conflict on the relationship between leader–member exchange and relative deprivation: Links to behavioral outcomes. Tour. Manag. 2016, 54, 369–382. [Google Scholar]

- Schilpzand, P.; Leavitt, K.; Lim, S. Incivility hates company: Shared incivility attenuates rumination, stress, and psychological withdrawal by reducing self-blame. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2016, 133, 33–44. [Google Scholar]

- Han, S.J.; Bonn, M.A.; Cho, M. The relationship between customer incivility, restaurant frontline service employee burnout and turnover intentions. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 52, 97–106. [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai, K.; Jex, S.M. Coworker incivility and incivility targets’ work effort and counterproductive work behaviors: The moderating role of supervisor social support. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2012, 17, 150–161. [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai, K.; Jex, S.; Gillespie, M. Negative work-family spillover of affect due to workplace incivility. Jpn. Assoc. Ind./Organ. Psychol. J. 2011, 25, 13–23. [Google Scholar]

- Karatepe, O.M.; Magaji, A.B. Work-family conflict and facilitation in the hotel industry: A study in Nigeria. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2008, 49, 395–412. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, K.H.; Baker, M.A.; Murmann, S.K. When we are onstage, we smile: The effects of emotional labor on employee work outcomes. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 906–915. [Google Scholar]

- Porath, C.L.; Pearson, C.M. The cost of bad behavior. Organ. Dyn. 2010, 39, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, L.M.; Pearson, C.M. Tit for tat? The spiraling effect of incivility in the workplace. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1999, 24, 452–471. [Google Scholar]

- Hur, W.M.; Kim, B.S.; Park, S.J. The relationship between coworker incivility, emotional exhaustion, and organizational outcomes: The mediating role of emotional exhaustion. Hum. Factors Ergon. Manuf. Serv. Ind. 2015, 25, 701–712. [Google Scholar]

- Hur, W.M.; Moon, T.; Jun, J.K. The effect of workplace incivility on service employee creativity: The mediating role of emotional exhaustion and intrinsic motivation. J. Serv. Mark. 2016, 30, 302–315. [Google Scholar]

- Van Jaarsveld, D.D.; Walker, D.D.; Skarlicki, D.P. The role of job demands and emotional exhaustion in the relationship between customer and employee incivility. J. Manag. 2010, 36, 1486–1504. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, S.; Cortina, L.M.; Magley, V.J. Personal and workgroup incivility: Impact on work and health outcomes. J. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 93, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penney, L.M.; Spector, P.E. Job stress, incivility, and counterproductive work behavior (CWB): The moderating role of negative affectivity. J. Organ. Behav. 2005, 26, 777–796. [Google Scholar]

- Zsigmond, T.; Mura, L. Emotional intelligence and knowledge sharing as key factors in business management—Evidence from Slovak SMEs. Econ. Sociol. 2023, 16, 248–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatepe, O.M.; Aleshinloye, K.D. Emotional dissonance and emotional exhaustion among hotel employees in Nigeria. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2009, 28, 349–358. [Google Scholar]

- Karatepe, O.M.; Olugbade, O.A. The effects of work social support and career adaptability on career satisfaction and turnover intentions. J. Manag. Organ. 2017, 23, 337–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatepe, O.M.; Yorganci, I.; Haktanir, M. Outcomes of customer verbal aggression among hotel employees. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2009, 21, 713–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schilpzand, P.; De Pater, I.E.; Erez, A. Workplace incivility: A review of the literature and agenda for future research. J. Organ. Behav. 2016, 37, S57–S88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatepe, O.M.; Olugbade, O.A. The mediating role of work engagement in the relationship between high-performance work practices and job outcomes of employees in Nigeria. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 28, 2350–2371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Yongjian, P.; Shahzad, F.; Hussain, I.; Zhang, D.; Fareed, Z.; Hameed, F.; Wang, C. Abusive Supervision and Turnover Intentions: A Mediation-Moderation Perspective. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diefendorff, J.M.; Croyle, M.H. Antecedents of emotional display rule commitment. Hum. Perform. 2008, 21, 310–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, G.A.; Webster, J.R. Emotional regulation as a mediator between interpersonal mistreatment and distress. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2013, 22, 697–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am. Psychol. 1989, 44, 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pizam, A. Depression among foodservice employees. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2008, 27, 135–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, B.; Tsu Wee Tan, T.; Julian, C. The theoretical underpinnings of emotional dissonance: A framework and analysis of propositions. J. Serv. Mark. 2006, 20, 471–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reio, T.G., Jr. Supervisor and coworker incivility: Testing the work frustrationaggression model. Adv. Dev. Hum. Resour. 2011, 13, 54–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.; Cortina, L.M. Interpersonal mistreatment in the workplace: The interface and impact of general incivility and sexual harassment. J. Appl. Psychol. 2005, 90, 483–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortina, L.M.; Magley, V.J.; Williams, J.H.; Langhout, R.D. Incivility in the workplace: Incidence and impact. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2001, 6, 64–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, S.; Hussain, I.; Shahzad, F.; Afaq, A. A Multidimensional Model of Abusive Supervision and Work Incivility. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boles, J.S.; Johnston, M.W.; Hair, J.F., Jr. Role stress, work-family conflict and emotional exhaustion: Inter-relationships and effects on some work-related consequences. J. Pers. Sell. Sales Manag. 1997, 17, 17–28. [Google Scholar]

- Mohsin, A.; Lengler, J.; Aguzzoli, R. Staff turnover in hotels: Exploring the quadratic and linear relationships. Tour. Manag. 2015, 51, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoresen, C.J.; Kaplan, S.A.; Barsky, A.P.; Warren, C.R.; De Chermont, K. The affective underpinnings of job perceptions and attitudes: A meta-analytic review and integration. Psychol. Bull. 2003, 129, 914–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yavas, U.; Babakus, E.; Karatepe, O.M. Attitudinal and behavioral consequences of work-family conflict and family-work conflict: Does gender matter? Int. J. Serv. Ind. Manag. 2008, 19, 7–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, E.A. What is job satisfaction? Organ. Behav. Hum. Perform. 1969, 4, 309–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulki, J.P.; Jaramillo, F.; Locander, W.B. Emotional exhaustion and organizational deviance: Can the right job and a leader’s style make a difference? J. Bus. Res. 2006, 59, 1222–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandey, A.A. When “the show must go on”: Surface acting and deep acting as determinants of emotional exhaustion and peer-rated service delivery. Acad. Manag. J. 2003, 46, 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunsaker, W.D.; Ding, W. Workplace spirituality and innovative work behavior: The role of employee flourishing and workplace satisfaction. Empl. Relat. Int. J. 2022, 44, 1355–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladebo, O.J.; Awotunde, J.M. Emotional and behavioral reactions to work overload: Self-efficacy as a moderator. Curr. Res. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 13, 86–100. [Google Scholar]

- Caillier, J.G. The impact of workplace aggression on employee satisfaction with job stress, meaningfulness of work, and turnover intentions. Public Pers. Manag. 2021, 50, 159–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voordt, T.V.D.; Jensen, P.A. The impact of healthy workplaces on employee satisfaction, productivity and costs. J. Corp. Real Estate 2023, 25, 29–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, M.; Bonn, M.A.; Han, S.J.; Lee, K.H. Workplace incivility and its effect upon restaurant frontline service employee emotions and service performance. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 28, 2888–2912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, J.E. Why is this happening? A causal attribution approach to work exhaustion consequences. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2000, 25, 335–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatepe, O.M. High-performance work practices, work social support and their effects on job embeddedness and turnover intentions. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 25, 903–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.J.; Ok, C. Reducing burnout and enhancing job satisfaction: Critical role of hotel employees’ emotional intelligence and emotional labor. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 1101–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbuckle, J.L. Amos, version 20.0; IBM SPSS: Chicago, IL, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis: A Global Perspective, 7th ed.; Pearson Education: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain, I.; Ali, S.; Shahzad, F.; Irfan, M.; Wan, Y.; Fareed, Z.; Sun, L. Abusive Supervision Impact on Employees’ Creativity: A Mediated-Moderated Perspective. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Zhou, E. Influence of customer verbal aggression on employee turnover intention. Manag. Decis. 2013, 51, 890–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeyemi, A.Y.; Ojo, S.O.; Aina, O.O.; Olanipekun, E.A. Empirical evidence of women under-representation in the construction industry in Nigeria. Women Manag. Rev. 2006, 21, 567–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiter, M.P.; Maslach, C. Nurse turnover: The mediating role of burnout. J. Nurs. Manag. 2009, 17, 331–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olugbade, O.A. The career adapt-abilities scale-Nigeria form: Psychometric properties and construct validity. J. Vocat. Behav. 2016, 95, 111–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeola, O.; Ezenwafor, K. The hospitality business in Nigeria: Issues, challenges and opportunities. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2016, 8, 182–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.J.; Kim, W.G.; Zhao, X.R. Multilevel model of management support and casino employee turnover intention. Tour. Manag. 2017, 59, 193–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C. Burnout: A multidimensional perspective. In Professional Burnout: Recent Developments in Theory and Research; Series in applied psychology: Social issues and questions; Schaufeli, W.B., Maslach, C., Marek, T., Eds.; Taylor & Francis: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1993; pp. 19–32. [Google Scholar]

- Okpara, J.O. Gender and the relationship between perceived fairness in pay, promotion, and job satisfaction in a sub-Saharan African economy. Women Manag. Rev. 2006, 21, 224–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccoli, G.; Lui, T.W.; Grün, B. The impact of IT-enabled customer service systems on service personalization, customer service perceptions, and hotel performance. Tour. Manag. 2017, 59, 349–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porath, C.L.; Foulk, T.; Erez, A. How incivility hijacks performance. Organ. Dyn. 2015, 44, 258–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sliter, M.; Jex, S.; Wolford, K.; McInnerney, J. How rude! Emotional labor as a mediator between customer incivility and employee outcomes. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2010, 15, 468–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Atributes | Frequency % | Values | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 19–24 | 34 | 11.5 |

| 15–32 | 121 | 40.4 | |

| 33–40 | 105 | 35.5 | |

| 41–49 | 35 | 12.3 | |

| 50 above | 10 | 0.3 | |

| Sex | Male | 198 | 64.9 |

| Female | 107 | 35.1 | |

| Marital Status | Unmarried | 155 | 50.8 |

| Married | 150 | 49.2 | |

| Qualifications | Secondary School | 50 | 16.3 |

| Graduate | 150 | 49.3 | |

| Masters | 105 | 34.4 | |

| Experience | <1 year | 70 | 23.0 |

| 1 to 4 | 60 | 19.5 | |

| 5 to 8 | 130 | 42.5 | |

| 9 and above | 45 | 15.0 |

| Scale Items | Loadings | t-Value | CR | AVE | α |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Customer incivility | 0.85 | 0.51 | 0.87 | ||

| Customers show anger at me | 0.90 | 1.00 a | |||

| Customers pass bad comments toward me | 0.85 | 18.60 | |||

| Customers made us feel that we are inferior | 0.63 | 13.69 | |||

| Customers show themselves as irritated | 0.63 | 13.82 | |||

| Customers don’t have to trust on my information and reconfirm it from top-management | 0.60 | 12.90 | |||

| Customer doubts about my competency | 0.59 | 12.75 | |||

| Employees’ Emotional Exhaustion | 0.89 | 0.59 | 0.88 | ||

| I sense emotionally exhausted from work | 0.73 | 1.00 a | |||

| I sense sadness at end of day | 0.80 | 13.33 | |||

| I sense fatigued in the morning when I get up and feel whole the day boring | 0.85 | 14.13 | |||

| I sense mental pressure all-day | 0.74 | 12.21 | |||

| I feel psychological distress at the workplace | 0.75 | 12.36 | |||

| Employees’ Intention to quit the Workplace | 0.91 | 0.75 | 0.90 | ||

| It seems that I’ll search new job soon | 0.81 | 1.00 a | |||

| I mostly think about leaving this job | 0.93 | 18.20 | |||

| Maybe next year I’ll leave this job | 0.77 | 15.47 | |||

| Satisfaction at workplace | 0.90 | 0.74 | 0.92 | ||

| My job make me a sense of satisfaction | 0.80 | 1.00 a | |||

| I really enjoy at workplace | 0.79 | 16.85 | |||

| I am very much satisfied with my work | 0.81 | 15.49 |

| Variables | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Customers incivility | 2.91 | 0.92 | - | |||

| Emp. Emo Exh | 3.19 | 0.90 | 0.34 ** | - | ||

| Emp. Int. to quit | 3.09 | 0.88 | 0.27 ** | 0.30 ** | - | |

| Satisfaction at work | 2.78 | 1.01 | −0.17 ** | −0.28 ** | −0.052 ** | - |

| Hypothesized Mediation Relationship | Unstandardized Indirect Estimates | LLCI | ULCI | p< |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Customer Incivility Emo. Exh Turnover intensions (0.229 a × 0.323 b) | 0.081 | 0.039 | 0.128 | 0.001 |

| Customer Incivility Emo. Exh Satisfaction at work (0.229 a × −0.399 b) | −0.089 | −0.158 | −0.049 | 0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shahzad, F.; Ali, S.; Hussain, I.; Sun, L.; Wang, C.; Ahmad, F. The Impact of Customer Incivility and Its Consequences on Hotel Employees: Mediating Role of Employees’ Emotional Exhaustion. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15211. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152115211

Shahzad F, Ali S, Hussain I, Sun L, Wang C, Ahmad F. The Impact of Customer Incivility and Its Consequences on Hotel Employees: Mediating Role of Employees’ Emotional Exhaustion. Sustainability. 2023; 15(21):15211. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152115211

Chicago/Turabian StyleShahzad, Farrukh, Shahab Ali, Iftikhar Hussain, Li Sun, Chunlei Wang, and Fayyaz Ahmad. 2023. "The Impact of Customer Incivility and Its Consequences on Hotel Employees: Mediating Role of Employees’ Emotional Exhaustion" Sustainability 15, no. 21: 15211. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152115211

APA StyleShahzad, F., Ali, S., Hussain, I., Sun, L., Wang, C., & Ahmad, F. (2023). The Impact of Customer Incivility and Its Consequences on Hotel Employees: Mediating Role of Employees’ Emotional Exhaustion. Sustainability, 15(21), 15211. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152115211