Using the Collaborative Problem-Solving Model: Findings from an Evaluation of U.S. EPA’s Environmental Justice Academy

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. EJ Academy Program Overview

2.2. Study Population and Data Collection Procedures

2.3. Measurement

3. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Description of EJ Academy Participants

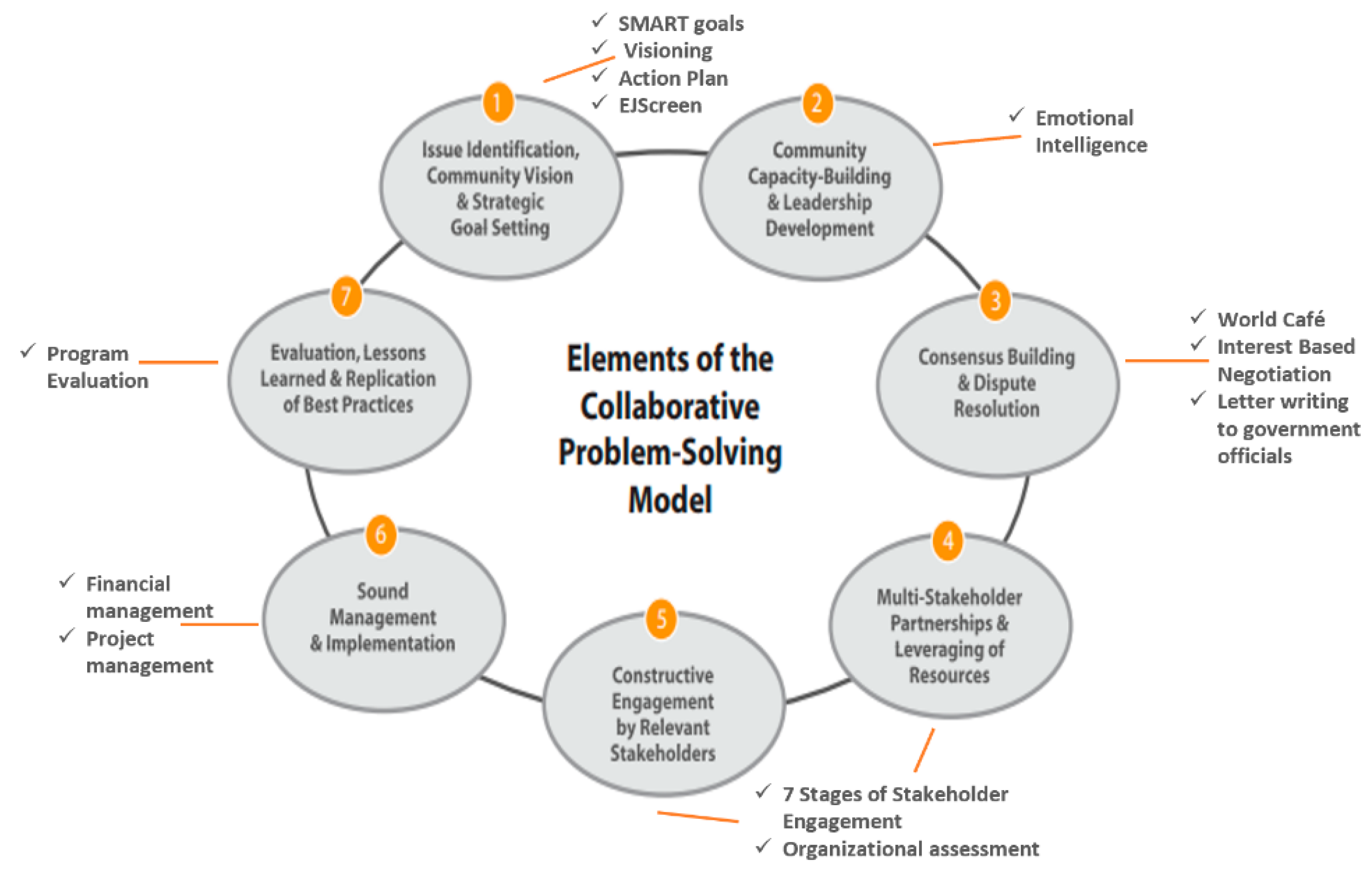

4.2. The Collaborative Problem-Solving Model Implementation

4.3. Barriers and Facilitators of Project Implementation

4.4. Ways in Which the CPS Model Has Strengthened Community Efforts to Address Community Change

4.5. Community Changes

5. Discussion

5.1. EJ Academy Model and CPS Implementation

5.2. Alignment of CPS Model with Other Community-Engaged Approaches and Leadership Trainings

5.3. Making Strides toward Environmental Justice

5.4. Strengths and Limitations

5.5. Research, Policy, and EJ Implications

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Freudenberg, N.; Pastor, M.; Israel, B. Strengthening community capacity to participate in making decisions to reduce disproportionate environmental exposures. Am. J. Public Health 2011, 101 (Suppl. S1), S123–S130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker, E.A.; Chung, L.K.; Israel, B.A.; Reyes, A.; Wilkins, D. Community organizing network for environmental health: Using a community health development approach to increase community capacity around reduction of environmental triggers. J. Prim. Prev. 2010, 31, 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raine, K.D.; Plotnikoff, R.; Schopflocher, D.; Lytvyak, E.; Nykiforuk, C.I.; Storey, K.; Ohinmaa, A.; Purdy, L.; Veugelers, P.; Wild, T.C. Healthy Alberta Communities: Impact of a three-year community-based obesity and chronic disease prevention intervention. Prev. Med. 2013, 57, 955–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, P.; Gold, A.; Abbott, A.; Contreras, D.; Keim, A.; Oscarson, R.; Procter, S.; Remig, V.; Smathers, C.; Mobley, A.R. A quasi-experimental study to mobilize rural low-income communities to assess and improve the ecological environment to prevent childhood obesity. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Praxis Project. Communities Creating Healthy Environments: A National Program of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Subica, A.M.; Grills, C.T.; Douglas, J.A.; Villanueva, S. Communities of Color Creating Healthy Environments to Combat Childhood Obesity. Am. J. Public Health 2016, 106, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motley, M.; Holmes, A.; Hill, J.; Plumb, K.; Zoellner, J. Evaluating community capacity to address obesity in the Dan River region: A case study. Am. J. Health Behav. 2013, 37, 208–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amed, S.; Naylor, P.J.; Pinkney, S.; Shea, S.; Mâsse, L.C.; Berg, S.; Collet, J.P.; Wharf Higgins, J. Creating a collective impact on childhood obesity: Lessons from the SCOPE initiative. Can. J. Public Health 2015, 106, e426–e433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subica, A.M.; Grills, C.T.; Villanueva, S.; Douglas, J.A. Community Organizing for Healthier Communities: Environmental and Policy Outcomes of a National Initiative. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2016, 51, 916–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US Environmental Protection Agency Office of Environmental Justice (EPA OEJ). EPA’s Environmental Justice Collaborative Problem Solving-Model; US Environmental Protection Agency Office of Environmental Justice (EPA OEJ): Washington, DC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, S.M.; Wilson, O.R.; Heaney, C.D.; Cooper, J. Use of EPA collaborative problem-solving model to obtain environmental justice in North Carolina. Prog Community Health Partnersh 2007, 1, 327–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US Environmental Protection Agency Office of Environmental Justice (EPA OEJ). Fact Sheet on Environmental Justice Collaborative Problem-Solving Coopertive Agreement Program; US Environmental Protection Agency Office of Environmental Justice (EPA OEJ): Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- US Environmental Protection Agency Office of Environmental Justice (EPA OEJ). Case Studies from the Environmental Justice Collaborative Problem-Solving Program, Models for Success; US Environmental Protection Agency Office of Environmental Justice (EPA OEJ): Washington, DC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Tennessee, D.; Office of Environmental Justice, U.S.E.P.A. Environmental Justice in Action: EPA Celebrates Inaugural Environmental Justice Academy Graduation. In: The EPA Blog; 2016. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/archive/epa/newsreleases/epa-celebrates-inaugural-environmental-justice-academy-graduation.html (accessed on 12 July 2020).

- Cooperrider, D.; Whitney, D.D.; Stavros, J.M.; Stavros, J. The Appreciative Inquiry Handbook: For Leaders of Change; Berrett-Koehler Publishers: Oakland, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Top Achievement-Self Improvement Personal Development Community Creating, S.M.A.R.T. Goals. Available online: http://topachievement.com/smart.html (accessed on 12 July 2023).

- National Association of County and City Health Officials (NACCHO). Visioning. Available online: Naccho.org/programs/public-health-infrastructure/performance-improvement/community-health-assessment/mapp/phase-2-visioning (accessed on 12 July 2023).

- EJSCREEN. Environmental Justice Screening and Mapping Tool; EPA: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- HelpGuideOrg International. Improving Emotional Intelligence. Available online: http://www.helpguide.org/articles/emotional-health/emotional-intelligence-eq.htm (accessed on 12 July 2023).

- The World Cafe Community Foundation. the World Cafe: Design Principles. Available online: http://www.theworldcafe.com/key-concepts-resources/design-principles/# (accessed on 12 July 2023).

- Fisher, R.; Ury, W.L.; Patton, B. Getting to Yes: Negotiating Agreement without Giving in; Penguin: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Community Toolbox. Chapter 7-Encouraging Involvement in Community Work: Section 8-Identifying and Analyzing Stakeholders and Their Interests. Available online: http://ctb.ku.edu/en/table-of-contents/participation/encouraging-involvement/identify-stakeholders/main (accessed on 12 July 2023).

- Community Toolbox. Chapter 42-Getting Grants and Financial Resources: Section 1-Developing a Plan for Financial Sustainability. Available online: http://ctb.ku.edu/en/table-of-contents/finances/grants-and-financial-resources/financial-sustainability/main (accessed on 12 July 2023).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. A Framework for Program Evaluation. Available online: http://www.cdc.gov/eval/framework/index.htm (accessed on 12 July 2023).

- Qualtrics. Qualtircs Survey Software; copyright year 2020 Qualtrics XM: Provo, UT, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Maclellan-Wright, M.F.; Anderson, D.; Barber, S.; Smith, N.; Cantin, B.; Felix, R.; Raine, K. The development of measures of community capacity for community-based funding programs in Canada. Health Promot Int. 2007, 22, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bopp, M.; Germann, K.; Bopp, J.; Baugh Littlejohns, L.; Smith, N. Assessing community capacity for change. In Red Deer, Alberta: David Thompson Health Region & Four Worlds Centre for Development Learning; Red Deer: Alberta, QC, Canada, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Kegler, M.C.; Hermstad, A.; Haardörfer, R. Evaluation Design for The Two Georgias Initiative: Assessing Progress Toward Health Equity in the Rural South. Health Educ. Behav. 2023, 50, 268–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laverack, G. Health Promotion Practice; McGraw Hill Open University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- US Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Environmental Justice (EPA OEJ). Environmental Justice Collaborative Problem-Solving Coopertive Agreement Program; US Environmental Protection Agency Office of Environmental Justice (EPA OEJ): Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W.; Clark, V.L.P. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research, 2nd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- IBMSS. Statistics for Windows [Computer Software], Version 27.0; IBM Corp.: Armonk, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hennink, M.; Hutter, I.; Bailey, A. Qualitative Research Methods; Sage: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case study Research and Applications: Design and Methods, 6th ed.; Sage publications: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- MAXQDA. VERBI Software [computer software], copyright year 2020v; Maxqda: Berlin, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Israel, B.; Schulz, A.; Parker, E.; Becker, A. Review of community-based research: Assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annu Rev Public Health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 1998, 19, 173–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bacon, C.; deVuono-Powell, S.; Frampton, M.L.; LoPresti, T.; Pannu, C. Introduction to empowered partnerships: Community-based participatory action research for environmental justice. Environ. Justice 2013, 6, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heaney, C.; Wilson, S.; Wilson, O.; Cooper, J.; Bumpass, N.; Snipes, M. Use of community-owned and -managed research to assess the vulnerability of water and sewer services in marginalized and underserved environmental justice communities. J Environ Health. 2011, 74, 8–17. [Google Scholar]

- O’Fallon, L.R.; Dearry, A. Community-based participatory research as a tool to advance environmental health sciences. Environ. Health Perspect. 2002, 110 (Suppl. S2), 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Israel, B.A.; Coombe, C.M.; Cheezum, R.R.; Schulz, A.J.; McGranaghan, R.J.; Lichtenstein, R.; Reyes, A.G.; Clement, J.; Burris, A. Community-based participatory research: A capacity-building approach for policy advocacy aimed at eliminating health disparities. Am. J. Public Health 2010, 100, 2094–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minkler, M. Linking science and policy through community-based participatory research to study and address health disparities. Am. J. Public Health 2010, 100, S81–S87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minkler, M.; Garcia, A.P.; Rubin, V.; Wallerstein, N. Community-Based Participatory Research: A Strategy for Building Healthy Communities and Promoting Health through Policy Change; PolicyLink: Oakland, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Themba, M.; Minkler, M.; Freudenberg, N. The role of CBPR in policy advocacy. In Community-Based Participatory Research for Health: From Process to Outcomes, 2nd ed.; Minkler, M.W.N., Ed.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2008; pp. 307–323. [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein, N.; Duran, B. Community-based participatory research contributions to intervention research: The intersection of science and practice to improve health equity. Am. J. Public Health 2010, 100, S40–S46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, W.K. Integrating research and action: A systematic review of community-based participatory research to address health disparities in environmental and occupational health in the USA. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2008, 62, 668–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freudenberg, N.; Tsui, E. Evidence, power, and policy change in community-based participatory research. Am. J. Public Health 2014, 104, 11–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US Environmental Protection Agency. What Is Citizen Science? Available online: https://www.epa.gov/citizen-science (accessed on 12 July 2020).

- Wilson, S.; Aber, A.; Wright, L.; Vivek, R. A review of community-engaged research approaches used to achieve environmental justice and eliminate disparities. In Routledge Handbook of Environmental Justice; Holifield, R., Chakraborty, J., Walker, G., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; pp. 283–296. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, O.; Wilson, S. Assessment of a Novel Environmental Justice Community University Partnership. In Advancing Environmental Justice, Contributions of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences Division of Extramural Research and Training to Environmental Justice: 1998–2012; National Institutes of Environmental Health Sciences NIH, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Washington, DC, USA, 2015; p. 26. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. EPA Region 4 Office of Environmental Justice, Environmental Justice Academy. Discovering Your Power: Program Launch and Orientation; EPA: Washington, DC, USA, 2015; p. 129. [Google Scholar]

- Zartarian, V.; Schultz, B.; Lakin, M.; Smuts, M. EPA’s Community-Friendly Exposure and Risk Screening Tool. Epidemiology 2008, 19, S188. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, S.; Hutson, M.; Mujahid, M. How planning and zoning contribute to inequitable development, neighborhood health, and environmental injustice. Environ. Justice 2009, 1, 211–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| CPS Model Elements | Description | Measurement | Items/Scale Reliability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Element 1: issue identification, community vision, and strategic goal setting. | Element 1 involves identifying the problem, envisioning possible solutions and then setting goals to achieve those solutions. Often people come together when they realize that something is wrong, and awareness of the problem is key to formulating strategies to resolve them. The visioning process is a way to think about what the community should look like and helps to establish community goals. Goals then serve as the foundation for formulating specific solutions or desired outcomes for a particular health and/or environmental problem. | Quantitative Measures: Eight survey items (related to understanding history, community values, and prioritizing concerns); five author-developed and three items adapted from the MacLeelan-Wright et al. [26] community capacity scale related to critical reflection. Qualitative Measures: Three interview questions were asked pertaining to the description of the focal EJ concern and how this issue was prioritized. | 8 items α = 0.77 |

| Element 2: community capacity building and leadership development. | Element 2 identifies the necessity of skills, information, and resources to achieve goals. The rationale is that when residents develop a greater understanding of environmental concerns, they can understand the options available to address these concerns and subsequently acquire a greater capacity to meaningfully engage in the decision-making process. Leadership development is an important component to capacity building as certain qualities such as strategic thinking, creating vision, management, effective communication, and consensus-building are necessary to achieve positive results. | Quantitative Measures: Thirteen author-created survey items (related to community participation, community-centered capacity building strategies, and leadership opportunities). Qualitative Measures: Two interview questions were asked pertaining to learned EJ Academy activities and strategies. | 13 items α = 0.75 |

| Element 3: consensus building and dispute resolution. | Element 3 details the importance of finding effective ways of making group decisions, involving appropriate constituents, and learning how to resolve disagreements. Collaborative problem-solving and consensus-building is a process that encourages agreement among differences, finding common ground among competing interests, meeting the needs and interests of all EJA Fellows, and creating solutions that are mutually beneficial for all. Differences of opinion naturally arise, and the application of consensus building approaches can be helpful in alleviating tensions and adversity. | Quantitative Measures: Eight survey items (related to diverse stakeholder involvement and conflict resolution) comprised of six author-created survey items and two items adapted from the Bopp et al. [27] resources scale and the Kegler et al. [28] skills development scale. Qualitative Measures: Three interview questions were asked related to a description of the project action plan, methods used to encourage diverse opinions and participation, and strategies used to solve conflict. | 8 items α = 0.78 |

| Element 4: multi-stakeholder partnership and leveraging resources. | Element 4 stresses the need for partnership to collectively examine problems, develop action plans, and bring together the resources necessary to achieve goals. Partnerships can be described as consisting of a diverse body of individuals or organizations that represent different sectors of society (i.e., community, government, business, industry, and academia) that are needed for mobilizing resources (i.e., social capital, institutional, technical, legal, and financial) to achieve a community’s vision. | Quantitative Measures: Six survey questions (related to the ability of participants to identify resources and develop partnerships) comprised of three author-created survey items and three adapted items from the Laverack et al. [29] community empowerment scale related to problem assessment. Qualitative Measures: Two interview questions were asked related to stakeholder involvement and network/partnership development. | 6 items α = 0.91 |

| Element 5: constructive engagement with other stakeholders. | Element 5 specifically identifies relevant non-community stakeholders (i.e., businesses, academia, civic organizations, and government) who can play an important role in collaborative partnerships. Specifically, business stakeholders who are often perceived as being the source of the problem, can benefit from being actively involved with the local community to increase communication and actively address policies and practices; government stakeholders can act as facilitators, provide technical assistance, assist in coordination and communications, provide services or financial resources, enforce laws/regulations, and provide legitimacy to an effort; and academia and civic organizations can provide training, technical assistance, and act as intermediaries for financial resources. | Quantitative Measures: Eight survey questions (describing the relationship with community partners and level of interaction with stakeholders) comprised of two author-created items and six adapted items from the Bopp et al. [27] community capacity scale related to participation and the MacLeelan-Wright et al. [26] community capacity scale related to resources. Qualitative Measures: One interview question was asked to further discuss engagement with non-community stakeholders. | 8 items α = 0.81 |

| Element 6: management and implementation. | Element 6 involves the development of sound management and organization that reflects the ability to identify and carry out work plans with clear goals, creation of a timeframe, and the delegation of responsibility to others. This process involves the identification of a leader/decision-maker who can foster consensus around the vision, establish operating procedures, manage action plans, and communicate properly with other stakeholders. | Quantitative Measures: Seven survey questions (related to leadership) comprised of two author-created items and five adapted items from the MacLeelan-Wright et al. [26] community capacity scale related to leadership. Qualitative Measures: Four interview questions were asked to detail the project action plan, resources needed, and future project plans. | 7 items α = 0.75 |

| Element 7: evaluation, lessons learned, and replication of best practices. | Element 7 discusses the necessity of determining whether a project is achieving its goals, identifying what is working or not working, and reviewing lessons learned in order to build on strengths and correct problems for future implementation. This element stresses that a focus on evaluation helps to clarify the underlying assumptions and relationships of the project, as well as identify opportunities and deficiencies that can be adjusted. | Quantitative Measures: Six survey questions (related to utilization of resources, and the degree to which the project has impacted the community) comprised of two items adapted from the Bopp et al. [27] community capacity scale related to resources and four items from the Laverack et al. [29] community empowerment scale related to problem assessment. Qualitative Measures: Four interview questions were asked to identify project goals, long-term vision, lessons learned, and project successes/challenges. | 6 items α = 0.86 |

| Survey Participants, n = 34 | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Professional affiliation | ||

| Academic activist | 5 | 14.7 |

| Community EJ advocates | 16 | 47.1 |

| College student activist | 13 | 38.2 |

| Location of EJ project | ||

| Alabama | 4 | 11.8 |

| Florida | 2 | 5.9 |

| Georgia | 17 | 50.0 |

| Maryland | 1 | 2.9 |

| Mississippi | 3 | 8.8 |

| South Carolina | 2 | 5.9 |

| Tennessee | 4 | 11.8 |

| Virginia | 1 | 2.9 |

| Interview Participants, n = 25 | n | % |

| Project Focus | ||

| Pollution and zoning | 6 | 24.0 |

| Green infrastructure/development | 6 | 24.0 |

| Food security and sustainable farming | 6 | 24.0 |

| Local redevelopment, workforce development, and environmental stewardship | 5 | 20.0 |

| Other: historical contextual research | 2 | 8.0 |

| Project Outcomes | ||

| Collaboration, partnership, and networking | 9 | 36.0 |

| Community education and skills development | 4 | 16.0 |

| Grant writing and new funding | 2 | 8.0 |

| Organizational infrastructure (e.g., 501c3 status) | 2 | 8.0 |

| Structural change (e.g., community revitalization) | 7 | 28.0 |

| Policy change | 1 | 4.0 |

| CPS Model Elements | # of Items | EJ Academy Fellow Element Implementation (n = 34, %) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M, SD | Low (None/Very Little) Range = 1.0–2.4 | Moderate (Somewhat) Range = 2.5–3.4 | High (Quite a Bit/a Great Deal) Range = 3.5–5.0 | ||

| Composite measure seven elements | 56 | 2.6, 0.5 | n = 9, 26.5% | n = 19, 55.9% | n = 6, 17.4% |

| Element 1: Issue identification, community vision, and goal setting | 8 | 3.3, 0.8 | n = 4, 11.8% | n = 11, 32.3 | n = 19, 55.9% |

| Element 2: Capacity building and leadership development | 13 | 1.9, 0.6 | n = 8, 23.5% | n = 21, 61.8% | n = 5, 14.7% |

| Element 3: Consensus building and dispute resolution | 8 | 3.3, 0.8 | n = 3, 8.8% | n = 14, 41.2% | n = 17, 50% |

| Element 4: Multi-stakeholder partnership and leveraging resources | 6 | 3.0, 0.9 | n = 9, 26.5% | n = 12, 35.3% | n = 13, 38.2% |

| Element 5: Constructive engagement with other stakeholders | 8 | 2.9, 0.8 | n = 7, 20.6% | n = 18, 52.9% | n = 9, 26.5% |

| Element 6: Management and implementation | 7 | 3.8, 0.7 | n = 2, 5.9% | n = 7, 20.6% | n = 25, 73.5% |

| Element 7: Evaluation, lessons learned, and replication of best practices | 6 | 3.2, 0.7 | n = 6, 17.6% | n = 17, 50% | n = 11, 32.3% |

| Barriers to Implementation | Facilitators of Implementation | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Lack of communication | A lack of ongoing communication with community stakeholders created challenges in advancing the project and reflected a need for better organizational infrastructure. | Strategic engagements | Those who had pre-existing, good working relationships with organizations, programs, and/or communities were beneficial for advancing project-related work. |

| Lack of funding | A lack of external financial resources and reliance on personal finances to advance the project was burdensome. | Detailed structure of curriculum | The EJA provided structure, tools, and skills that were beneficial, supportive, and provided a sense of empowerment needed for engaging in the EJ work related to project implementation. |

| Lack of community engagement | The lack of human/social capital and community involvement made many Fellows feel like “a team of one”. | Credibility of affiliation with the EJA | The teachings of the EJA have had a lasting impact beyond the mere implementation of specific community projects, and training created an opportunity to leverage the affiliation with the EJA for future work. |

| Lack of community connection | Developing partnerships, building trust, and establishing genuine community relationships were time-consuming and slowed project progress. | ||

| Lack of unity | Divisiveness and the lack of unity within the community or among partners of an organization was an impediment to the implementation of project activities. | Opportunities for networking | The EJA allowed for networking opportunities that were beneficial to achieving project goals and further developed skills necessary for future collaborations. |

| Difficulties in balancing competing priorities | Given the demand and time required with project implementation, many experienced challenges with finding the proper balance while weighing the importance of other life, school, work, and community priorities. | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Williamson, D.H.Z.; Good, S.; Wilson, D.; Jelks, N.O.; Johnson, D.A.; Komro, K.A.; Kegler, M.C. Using the Collaborative Problem-Solving Model: Findings from an Evaluation of U.S. EPA’s Environmental Justice Academy. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14999. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152014999

Williamson DHZ, Good S, Wilson D, Jelks NO, Johnson DA, Komro KA, Kegler MC. Using the Collaborative Problem-Solving Model: Findings from an Evaluation of U.S. EPA’s Environmental Justice Academy. Sustainability. 2023; 15(20):14999. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152014999

Chicago/Turabian StyleWilliamson, Dana H. Z., Sheryl Good, Daphne Wilson, Na’Taki Osborne Jelks, Dayna A. Johnson, Kelli A. Komro, and Michelle C. Kegler. 2023. "Using the Collaborative Problem-Solving Model: Findings from an Evaluation of U.S. EPA’s Environmental Justice Academy" Sustainability 15, no. 20: 14999. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152014999

APA StyleWilliamson, D. H. Z., Good, S., Wilson, D., Jelks, N. O., Johnson, D. A., Komro, K. A., & Kegler, M. C. (2023). Using the Collaborative Problem-Solving Model: Findings from an Evaluation of U.S. EPA’s Environmental Justice Academy. Sustainability, 15(20), 14999. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152014999