From Green Inclusive Leadership to Green Organizational Citizenship: Exploring the Mediating Role of Green Work Engagement and Green Organizational Identification in the Hotel Industry Context

Abstract

:1. Introduction

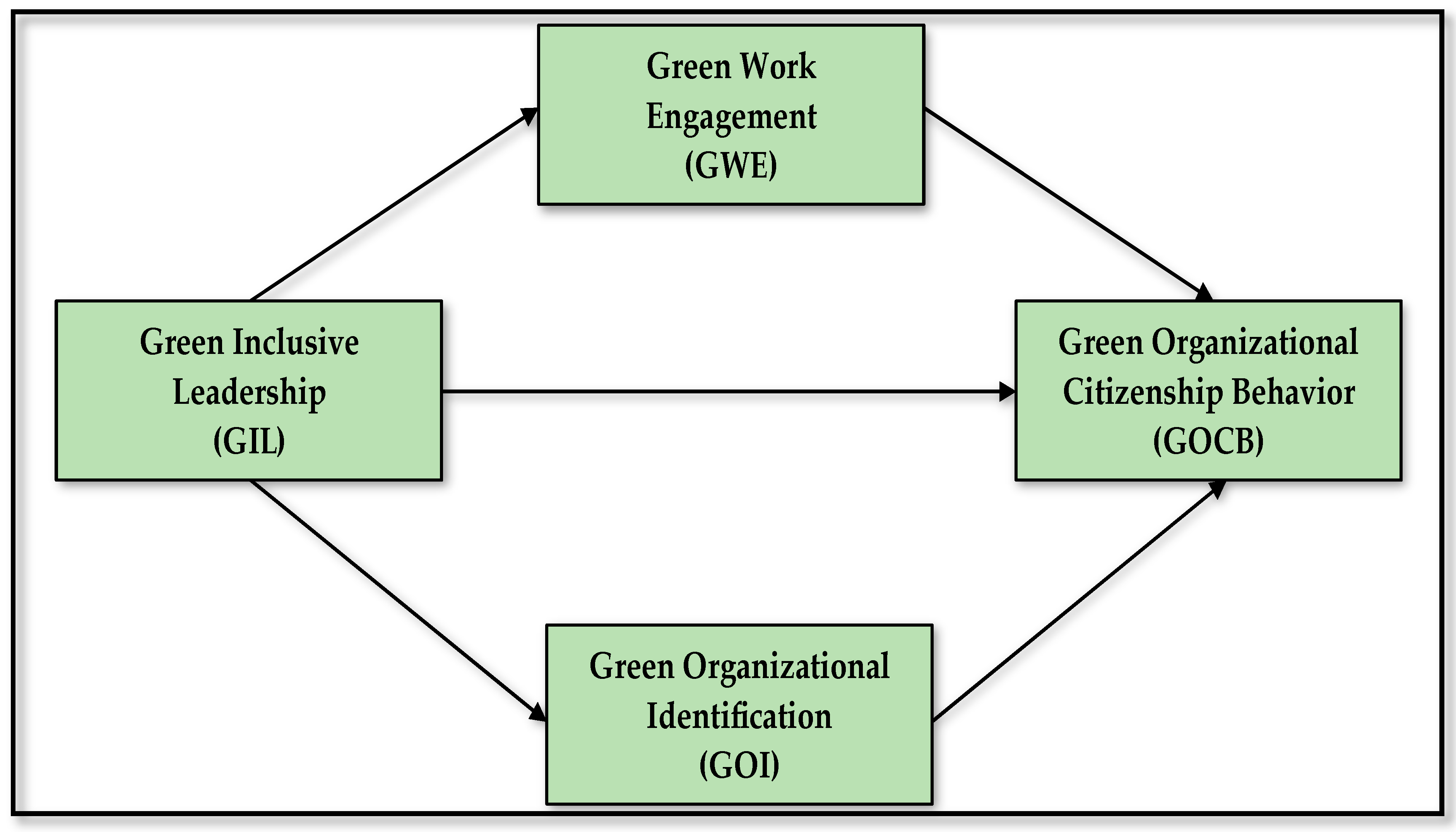

2. Review of Literature and Hypotheses Development

2.1. The Linkage between Green Inclusive Leadership and Employees’ GOCB

2.2. The Linkage between GIL and GWE

2.3. The Linkage between GIL and GOI

2.4. The Linkage between GWE and GOCB

2.5. The Linkage between GOI and GOCB

2.6. The Mediating Role of GWE in the GIL-GOCB Relationship

2.7. The Mediating Role of GOI in the GIL-GOCB Relationship

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Measurements of this Study

3.2. Study Sample and Data Collection

3.3. Data Analysis

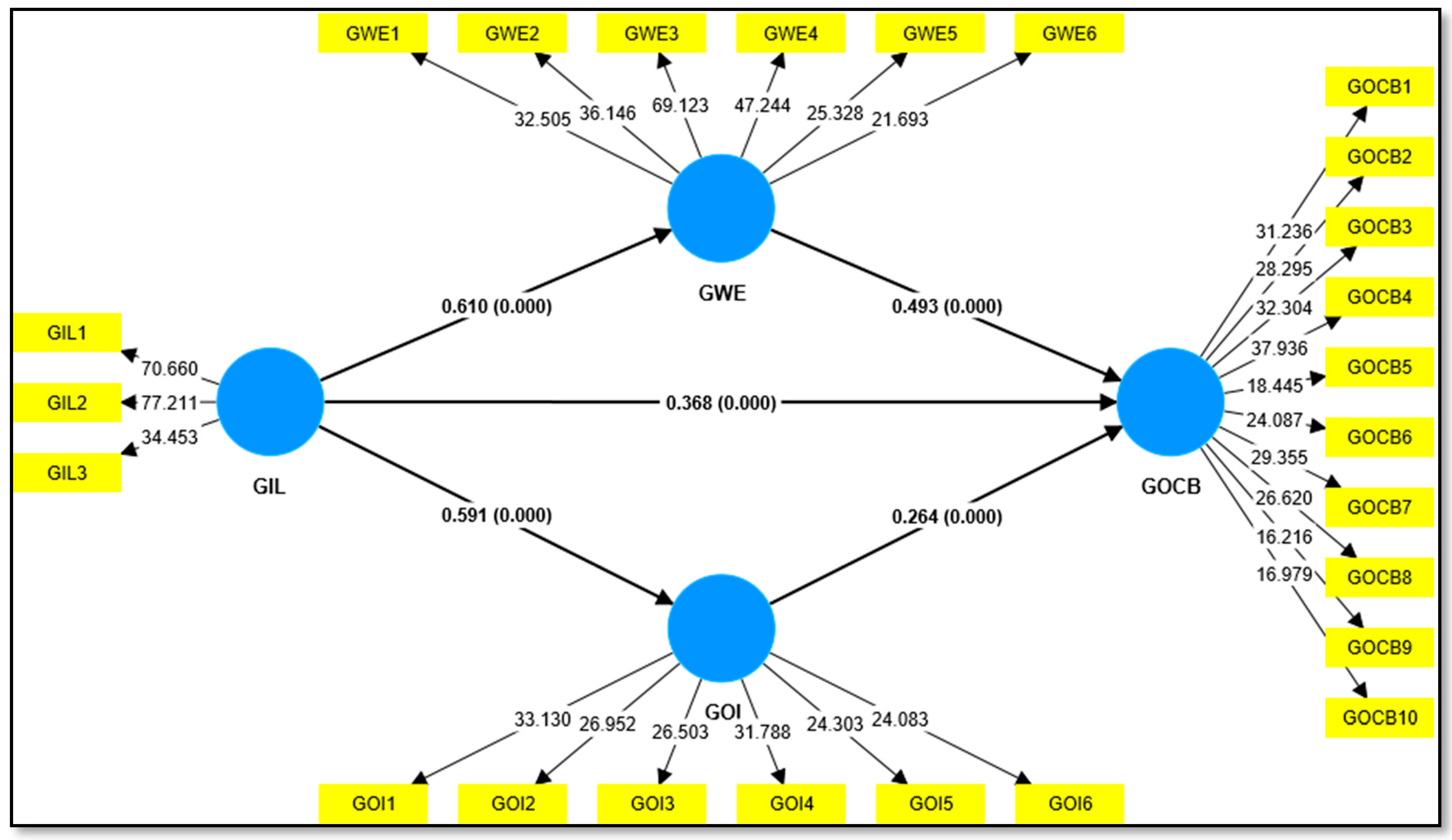

4. Results

4.1. Common Method Variance

4.2. The Measurement Model

4.3. Multicollinearity Statistics

4.4. Testing the Study Hypotheses

5. Discussion

6. Theoretical and Practical Implications

6.1. Theoretical Implications

6.2. Practical Implications

7. Research Limitations and Future Directions

8. Conclusions of the Study

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Construct | Items | Statement |

|---|---|---|

| Green Inclusive Leadership (GIL) | GIL1 | Your supervisor/manager is open to discussing pro-environmental goals at work and new green ways to achieve them. |

| GIL2 | Your supervisor/manager is available for consultation on environmental problems at work. | |

| GIL3 | Your supervisor/manager is ready to listen to requests related to handling environmental issues at work. | |

| Green Work Engagement (GWE) | GWE1 | Your environmental-related tasks inspire you. |

| GWE2 | You are proud of the environmental work that you do. | |

| GWE3 | You are deeply involved in your environmental work. | |

| GWE4 | You are enthusiastic about your environmental tasks at your job. | |

| GWE5 | You feel happy when you are working intensely on environmental tasks. | |

| GWE6 | With environmental tasks at your job, you feel bursting with energy. | |

| Green Organizational Identification (GOI) | GOI1 | You are highly aware of the hotel’s environmental management and conservation history. |

| GOI2 | You are proud of the hotel’s environmental goals and mission. | |

| GOI3 | You believe the hotel has achieved an essential position in environmental management and protection. | |

| GOI4 | You believe the hotel has established clear environmental objectives and missions. | |

| GOI5 | You are aware of the company’s environmental traditions and culture. | |

| GOI6 | You agree with the company’s actions in environmental management and protection. | |

| Green Organizational Citizenship Behavior (GOCB) | GOCB1 | In your work, you weigh the consequences of your actions before doing something that could affect the environment (Eco-initiatives). |

| GOCB2 | You voluntarily carry out environmental actions and initiatives in your daily work activities (Eco-initiatives). | |

| GOCB3 | You make suggestions to your colleagues about ways to protect the environment more effectively, even when it is not your direct responsibility (Eco-initiatives). | |

| GOCB4 | You actively participate in environmental events organized in and/or by your hotel (Eco-civic engagement). | |

| GOCB5 | You stay informed of your hotel’s environmental initiatives (Eco-civic engagement). | |

| GOCB6 | You undertake environmental actions that contribute positively to the image of your hotel (Eco-civic engagement). | |

| GOCB7 | You volunteer for projects, endeavors, or events that address environmental issues in your hotel (Eco-civic engagement). | |

| GOCB8 | You spontaneously give your time to help your colleagues take the environment into account in everything they do at work (Eco-helping). | |

| GOCB9 | You encourage your colleagues to adopt more environmentally conscious behavior (Eco-helping). | |

| GOCB10 | You encourage your colleagues to express their ideas and opinions on environmental issues (Eco-helping). |

References

- Aboramadan, M. The effect of green HRM on employee green behaviors in higher education: The mediating mechanism of green work engagement. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 2022, 30, 7–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhutto, T.A.; Farooq, R.; Talwar, S.; Awan, U.; Dhir, A. Green inclusive leadership and green creativity in the tourism and hospitality sector: Serial mediation of green psychological climate and work engagement. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 29, 1716–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, D.; Tian, L.; Qiu, W. The Study on the Influence of Green Inclusive Leadership on Employee Green Behaviour. J. Environ. Public Health 2022, 2022, 5292184 . [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patwary, A.K.; Mohd Yusof, M.F.; Bah Simpong, D.; Ab Ghaffar, S.F.; Rahman, M.K. Examining proactive pro-environmental behaviour through green inclusive leadership and green human resource management: An empirical investigation among Malaysian hotel employees. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2022. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboramadan, M.; Crawford, J.; Turkmenoglu, M.A.; Farao, C. Green inclusive leadership and employee green behaviors in the hotel industry: Does perceived green organizational support matter? Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 107, 103330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thabet, W.M.; Badar, K.; Aboramadan, M.; Abualigah, A. Does green inclusive leadership promote hospitality employees’ pro-environmental behaviors? The mediating role of climate for green initiative. Serv. Ind. J. 2023, 43, 43–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Jiang, L.; Cai, W.; Xu, B.; Gao, X. How Can Hotel Employees Produce Workplace Environmentally Friendly Behavior? The Role of Leader, Corporate, and Coworkers. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 725170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, L.; Yang, Y. Factors influencing green organizational citizenship behavior. Soc. Behav. Pers. 2020, 48, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, N.T.; Tučková, Z.; Chiappetta Jabbour, C.J. Greening the hospitality industry: How do green human resource management practices influence organizational citizenship behavior in hotels? A mixed-methods study. Tour. Manag. 2019, 72, 386–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luu, T.T. Green human resource practices and organizational citizenship behavior for the environment: The roles of collective green crafting and environmentally specific servant leadership. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 1167–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, J.; Murad, M.; Li, C.; Bakhtawar, A.; Ashraf, S.F. Green Lifestyle: A Tie between Green Human Resource Management Practices and Green Organizational Citizenship Behavior. Sustainability 2023, 15, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boiral, O.; Paillé, P. Organizational Citizenship Behaviour for the Environment: Measurement and Validation. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 109, 431–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Luo, F.; Zhu, X.; Huang, X.; Liu, Y. Inclusive Leadership Promotes Challenge-Oriented Organizational Citizenship Behavior Through the Mediation of Work Engagement and Moderation of Organizational Innovative Atmosphere. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 560594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bannay, D.F.; Hadi, M.J.; Amanah, A.A. The impact of inclusive leadership behaviors on innovative workplace behavior with an emphasis on the mediating role of work engagement. Probl. Perspect. Manag. 2020, 18, 479. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, T.; Chen, F.; Luan, H.; Chen, Y. Effect of Green Organizational Identity, Green Shared Vision, and Organizational Citizenship Behavior for the Environment on Green Product Development Performance. Sustainability 2019, 11, 617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire, C.; Pieta, P. The Impact of Green Human Resource Management on Organizational Citizenship Behaviors: The Mediating Role of Organizational Identification and Job Satisfaction. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Chen, J.; Wang, M.; Chen, C. The Impact of Inclusive Leadership on Employees’ Innovative Behaviors: The Mediation of Psychological Capital. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Xu, S.; Zhang, B. The Paradoxical Effect of Inclusive Leadership on Subordinates’ Creativity. Front. Psychol. 2020, 10, 2960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, T.B.H.; Choi, S.B. Effects of inclusive leadership on organizational citizenship behavior: The mediating roles of organizational justice and learning culture. J. Pac. Rim Psychol. 2019, 13, e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.B.; Tran, T.B.H.; Kang, S. Inclusive Leadership and Employee Well-Being: The Mediating Role of Person-Job Fit. J. Happiness Stud. 2017, 18, 1877–1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.; Kim, D.H.; Kim, D. The Impact of Inclusive Leadership and Autocratic Leadership on Employees’ Job Satisfaction and Commitment in Sport Organizations: The Mediating Role of Organizational Trust and The Moderating Role of Sport Involvement. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legrand, W.; Chen, J.S.; Laeis, G.C. Sustainability in the Hospitality Industry: Principles of Sustainable Operations; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Abdou, A.H.; Hassan, T.H.; Salem, A.E.; Elsaied, M.A.; Elsaed, A.A. Determinants and Consequences of Green Investment in the Saudi Arabian Hotel Industry. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasim, A. Towards a Wider Adoption of Environmental Responsibility in the Hotel Sector. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2007, 8, 25–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H. Consumer behavior and environmental sustainability in tourism and hospitality: A review of theories, concepts, and latest research. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 29, 1021–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatter, A.; McGrath, M.; Pyke, J.; White, L.; Lockstone-Binney, L. Analysis of hotels’ environmentally sustainable policies and practices: Sustainability and corporate social responsibility in hospitality and tourism. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 31, 2394–2410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdou, A.H.; Hassan, T.H.; El Dief, M.M. A Description of Green Hotel Practices and Their Role in Achieving Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, I.; Wisetsri, W.; Wu, H.; Shah, S.M.A.; Abbas, A.; Manzoor, S. Leadership styles and organizational citizenship behavior for the environment: The mediating role of self-efficacy and psychological ownership. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 683101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, C.; Patterson, M.; Dawson, J. Building work engagement: A systematic review and meta-analysis investigating the effectiveness of work engagement interventions. J. Organ. Behav. 2017, 38, 792–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Albrecht, S. Work engagement: Current trends. Career Dev. Int. 2018, 23, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Gancedo, J.; Fernández-Martínez, E.; Rodríguez-Borrego, M.A. Relationships among general health, job satisfaction, work engagement and job features in nurses working in a public hospital: A cross-sectional study. J. Clin. Nurs. 2019, 28, 1273–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbeanu, A.; Iliescu, D. The Link Between Work Engagement and Job Performance. J. Pers. Psychol. 2023, 22, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.; Salanova, M.; González-romá, V.; Bakker, A. The measurement of engagement and burnout: A two sample confirmatory factor analytic approach. J. Happiness Stud. 2002, 3, 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B.; Salanova, M. The measurement of work engagement with a short questionnaire: A cross-national study. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2006, 66, 701–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.B.; Tran, T.B.H.; Park, B.I. Inclusive Leadership and Work Engagement: Mediating Roles of Affective Organizational Commitment and Creativity. Soc. Behav. Pers. 2015, 43, 931–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cenkci, A.T.; Bircan, T.; Zimmerman, J. Inclusive leadership and work engagement: The mediating role of procedural justice. Manag. Res. News 2021, 44, 158–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, P.; Xiao, Z.; Bao, G.; Noorderhaven, N. Inclusive leadership and employee work engagement: A moderated mediation model. Balt. J. Manag. 2022, 17, 124–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudie, X.; Yun, C.; Fuqiang, Z. Inclusive leadership, perceived organizational support, and work engagement: The moderating role of leadership-member exchange relationship. In Proceedings of the 2017 7th International Conference on Social Network, Communication and Education (SNCE 2017), Shenyang, China, 28–30 July 2017; Atlantis Press: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 239–243. [Google Scholar]

- Vakira, E.; Shereni, N.C.; Ncube, C.M.; Ndlovu, N. The effect of inclusive leadership on employee engagement, mediated by psychological safety in the hospitality industry. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2023, 6, 819–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qasim, S.; Usman, M.; Ghani, U.; Khan, K. Inclusive Leadership and Employees’ Helping Behaviors: Role of Psychological Factors. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 888094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y. Green organizational identity: Sources and consequence. Manag. Decis. 2011, 49, 384–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soewarno, N.; Tjahjadi, B.; Fithrianti, F. Green innovation strategy and green innovation: The roles of green organizational identity and environmental organizational legitimacy. Manag. Decis. 2019, 57, 3061–3078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.; Li, Y.; Jing, Y.; Chen, B. A study of Inclusive leadership, organizational identification, and employee engagement. In Academy of Management Proceedings; Academy of Management: Briarcliff Manor, NY, USA, 2017; p. 17863. [Google Scholar]

- Song, J.; Wang, D.; He, C. Why and when does inclusive leadership evoke employee negative feedback-seeking behavior? Eur. Manag. J. 2023, 41, 292–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaabi, M.S.A.S.A.; Ahmad, K.Z.; Hossan, C. Authentic leadership, work engagement and organizational citizenship behaviors in petroleum company. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2016, 65, 811–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Guo, Y.; Newman, A. Identity judgments, work engagement, and organizational citizenship behavior: The mediating effects based on group engagement model. Tour. Manag. 2017, 61, 190–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farid, T.; Iqbal, S.; Ma, J.; Castro-González, S.; Khattak, A.; Khan, M.K. Employees’ Perceptions of CSR, Work Engagement, and Organizational Citizenship Behavior: The Mediating Effects of Organizational Justice. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastogi, A. Employee engagement and organizational effectiveness: The role of organizational citizenship behavior. Bus. Manag. Rev. 2013, 8, 129–136. [Google Scholar]

- Byaruhanga, I.; Othuma, B.P. Enhancing organizational citizenship behavior: The role of employee empowerment, trust and engagement. In Entrepreneurship and SME Management Across Africa: Context, Challenges, Cases; Springer: Singapore, 2016; pp. 87–103. [Google Scholar]

- Priskila, E.; Tecoalu, M.; Saparso; Tj, H.W. The Role of Employee Engagement in Mediating Perceived Organizational Support for Millennial Employee Organizational Citizenship Behavior. J. Soc. Sci. 2021, 2, 258–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheema, S.; Afsar, B.; Javed, F. Employees’ corporate social responsibility perceptions and organizational citizenship behaviors for the environment: The mediating roles of organizational identification and environmental orientation fit. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Mei, S.; Guo, Y. Green human resource management, green organization identity and organizational citizenship behavior for the environment: The moderating effect of environmental values. Chin. Manag. Stud. 2021, 15, 290–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Zhao, L. The Influence of Ethical Leadership and Green Organizational Identity on Employees’ Green Innovation Behavior: The Moderating Effect of Strategic Flexibility. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 237, 52012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Tang, W.; Wang, H.; Chen, Y. The Influence of Green Human Resource Management on Employee Green Behavior—A Study on the Mediating Effect of Environmental Belief and Green Organizational Identity. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Selm, M.; Jankowski, N.W. Conducting online surveys. Qual. Quant. 2006, 40, 435–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suliman, M.A.; Abdou, A.H.; Ibrahim, M.F.; Al-Khaldy, D.A.W.; Anas, A.M.; Alrefae, W.M.M.; Salama, W. Impact of green transformational leadership on employees’ environmental performance in the hotel industry context: Does green work engagement matter? Sustainability 2023, 15, 2690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stratton, S.J. Population Research: Convenience Sampling Strategies. Prehospital Disaster Med. 2021, 36, 373–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ETIC Hotels. Sustainable and Eco-Hotels in Saudi Arabia. 2023. Available online: https://etichotels.com/hotels?src=countries®id=6&conid=116&cityid=0&fromdt=na&todt=na&adlts=2&chlds=0 (accessed on 9 February 2023).

- Cantrell, M.A.; Lupinacci, P. Methodological issues in online data collection. J. Adv. Nurs. 2007, 60, 544–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loescher, L.; Hibler, E.; Hiscox, H.; Hla, H.; Harris, R. Challenges of Using the Internet for Behavioral Research. Comput. Inform. Nurs. 2011, 29, 445–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.; Bernstein, I.H. Psychometric Theory 3E; Tata McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Boomsma, A. On the Robustness of LISREL against Small Sample Sizes in Factor Analysis Models. Stat. Neerl. 1984, 38, 45–46. [Google Scholar]

- Nancarrow, C.; Brace, I.; Wright, L.T. Tell Me Lies, Tell Me Sweet Little Lies’: Dealing with Socially Desirable Responses in Market Research. Mark. Rev. 2001, 2, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randall, D.M.; Fernandes, M.F. The Social Desirability Response Bias in Ethics Research. J. Bus. Ethics 1991, 10, 805–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, D.; Clancy, K. Some effects of “Social Desirability” in Survey Studies. In Social Surveys; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2002; p. III37. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, R.A.; Yeolib, K. On the relationship between coefficient alpha and composite reliability. J. Appl. Psychol. 2013, 98, 194–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error: Algebra and Statistics. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelloway, E.K. Structural equation modelling in perspective. J. Organ. Behav. 1995, 16, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Lynch, J.G., Jr.; Chen, Q. Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: Myths and truths about mediation analysis. J. Consum. Res. 2010, 37, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, P.M. Social exchange. Int. Encycl. Soc. Sci. 1968, 7, 452–457. [Google Scholar]

| Characteristic | No. | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 329 | 73.8 |

| Female | 117 | 26.2 |

| Age | ||

| From 20 to 25 | 108 | 24.2 |

| More than 25 to 30 | 89 | 20.0 |

| More than 30 to 35 | 132 | 29.6 |

| More than 35 to 40 | 82 | 18.4 |

| More than 40 | 35 | 7.8 |

| Educational attainment | ||

| High school degree or equivalent | 77 | 17.2 |

| Diploma | 112 | 25.1 |

| University degree | 246 | 55.2 |

| Postgraduate degree | 11 | 2.5 |

| Department | ||

| Front Office | 96 | 21.5 |

| Housekeeping | 132 | 29.6 |

| Food and beverage | 152 | 34.1 |

| Others | 66 | 14.8 |

| Working experience in the hotel | ||

| 1–5 | 285 | 63.9 |

| More than 5 to 10 | 105 | 23.5 |

| More than 10 years | 56 | 12.6 |

| Total | 446 | 100% |

| Construct | Item | Mean | Standard Deviation | Outer Loading | α 1 | CR 2 | AVE 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Green Inclusive Leadership (GIL) | GIL1 | 4.17 | 0.911 | 0.884 *** | 0.838 | 0.903 | 0.756 |

| GIL2 | 4.24 | 0.939 | 0.906 *** | ||||

| Mean = 4.20 Standard deviation = 0.834 | GIL3 | 4.20 | 0.906 | 0.815 *** | |||

| Green Work Engagement (GWE) | GWE1 | 4.22 | 0.960 | 0.795 *** | 0.889 | 0.915 | 0.644 |

| GWE2 | 3.96 | 1.143 | 0.786 *** | ||||

| GWE3 | 4.45 | 0.837 | 0.874 *** | ||||

| GWE4 | 4.01 | 1.138 | 0.854 *** | ||||

| Mean = 4.12 | GWE5 | 4.12 | 1.000 | 0.748 *** | |||

| Standard deviation = 0.837 | GWE6 | 3.99 | 1.218 | 0.749 *** | |||

| Green Organizational Identification (GOI) | GOI1 | 3.97 | 0.821 | 0.793 *** | 0.840 | 0.882 | 0.555 |

| GOI2 | 4.01 | 0.810 | 0.753 *** | ||||

| GOI3 | 4.00 | 0.845 | 0.726 *** | ||||

| GOI4 | 3.95 | 0.849 | 0.745 *** | ||||

| Mean = 3.96 | GOI5 | 3.87 | 0.803 | 0.750 *** | |||

| Standard deviation = 0.736 | GOI6 | 3.98 | 0.998 | 0.700 *** | |||

| Green Organizational Citizenship Behavior (GOCB) | GOCB1 | 3.99 | 0.803 | 0.772 *** | 0.902 | 0.919 | 0.533 |

| GOCB2 | 4.01 | 0.810 | 0.655 *** | ||||

| GOCB3 | 4.15 | 0.826 | 0.764 *** | ||||

| GOCB4 | 4.20 | 0.900 | 0.756 *** | ||||

| GOCB5 | 3.91 | 0.867 | 0.803 *** | ||||

| GOCB6 | 4.11 | 0.979 | 0.658 *** | ||||

| GOCB7 | 4.16 | 0.871 | 0.736 *** | ||||

| GOCB8 | 3.97 | 0.849 | 0.753 *** | ||||

| Mean = 4.05 | GOCB9 | 3.96 | 0.849 | 0.738 *** | |||

| Standard deviation = 0.724 | GOCB10 | 4.02 | 0.821 | 0.646 *** |

| Construct | GIL | GOCB | GOI | GWE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GIL | 0.869 | |||

| GOCB | 0.525 | 0.730 | ||

| GOI | 0.591 | 0.428 | 0.745 | |

| GWE | 0.610 | 0.714 | 0.742 | 0.802 |

| Construct | GIL | GOCB | GOI | GWE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GIL | ||||

| GOCB | 0.633 | |||

| GOI | 0.699 | 0.536 | ||

| GWE | 0.705 | 0.822 | 0.849 |

| Construct | GIL | GOCB | GOI | GWE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GIL | 1.708 | 1.000 | 1.000 | |

| GOCB | ||||

| GOI | 2.389 | |||

| GWE | 2.473 |

| Hypothesized Path | Original Sample (O) | Sample Mean (M) | Standard Deviation (STDEV) | T Statistics | Confidence Intervals | Result | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.5% | 97.5% | ||||||

| Direct Path | |||||||

| H1: GIL ⟶ GOCB | 0.368 | 0.367 | 0.014 | 25.586 *** | 0.339 | 0.395 | Accepted |

| H2: GIL ⟶ GWE | 0.610 | 0.611 | 0.035 | 17.173 *** | 0.539 | 0.677 | Accepted |

| H3: GIL ⟶ GOI | 0.591 | 0.592 | 0.038 | 15.368 *** | 0.514 | 0.665 | Accepted |

| H4: GWE ⟶ GOCB | 0.493 | 0.494 | 0.018 | 26.907 *** | 0.458 | 0.529 | Accepted |

| H5: GOI ⟶ GOCB | 0.264 | 0.264 | 0.014 | 18.285 *** | 0.234 | 0.292 | Accepted |

| Indirect Path | |||||||

| H6: GIL ⟶ GWE ⟶ GOCB | 0.301 | 0.301 | 0.017 | 17.887 *** | 0.268 | 0.334 | Accepted |

| H7: GIL ⟶ GOI ⟶ GOCB | 0.156 | 0.156 | 0.013 | 11.589 *** | 0.130 | 0.183 | Accepted |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Abdou, A.H.; Al Abdulathim, M.A.; Hussni Hasan, N.R.; Salah, M.H.A.; Ali, H.S.A.M.; Kamel, N.J. From Green Inclusive Leadership to Green Organizational Citizenship: Exploring the Mediating Role of Green Work Engagement and Green Organizational Identification in the Hotel Industry Context. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14979. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152014979

Abdou AH, Al Abdulathim MA, Hussni Hasan NR, Salah MHA, Ali HSAM, Kamel NJ. From Green Inclusive Leadership to Green Organizational Citizenship: Exploring the Mediating Role of Green Work Engagement and Green Organizational Identification in the Hotel Industry Context. Sustainability. 2023; 15(20):14979. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152014979

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbdou, Ahmed Hassan, Majed Abdulaziz Al Abdulathim, Nadia Rebhi Hussni Hasan, Maha Hassan Ahmed Salah, Howayda Said Ahmed Mohamed Ali, and Nancy J. Kamel. 2023. "From Green Inclusive Leadership to Green Organizational Citizenship: Exploring the Mediating Role of Green Work Engagement and Green Organizational Identification in the Hotel Industry Context" Sustainability 15, no. 20: 14979. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152014979

APA StyleAbdou, A. H., Al Abdulathim, M. A., Hussni Hasan, N. R., Salah, M. H. A., Ali, H. S. A. M., & Kamel, N. J. (2023). From Green Inclusive Leadership to Green Organizational Citizenship: Exploring the Mediating Role of Green Work Engagement and Green Organizational Identification in the Hotel Industry Context. Sustainability, 15(20), 14979. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152014979