The Impact of User Benefits on Continuous Contribution Behavior Based on the Perspective of Stimulus–Organism–Response Theory

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Collective Action

2.2. User Benefits

2.3. Continuous Contribution Behavior

2.4. Future Work Self-Salience

2.5. Self-Verification Theory

2.6. Stimulus–Organism–Response (S-O-R) Theory

3. Hypothesis

3.1. User Benefits and Continuous Contribution Behavior

3.2. User Benefits and Self-Verification

3.3. Self-Verification and Continuous Contribution Behavior

3.4. The Mediating Role of Self-Verification

3.5. The Moderating Role of Future Work Self-Salience

4. Research Methodology

4.1. Sampling

4.2. Measures

4.3. Common Method Variance

4.4. Reliability and Validity

4.4.1. Reliability

4.4.2. Construct Validity

5. Results

- (1)

- The moderating role of future work self-salience on the relationship between social benefits and self-verification

- (2)

- The moderating role of future work self-salience on the relationship between economic benefits and self-verification

- (3)

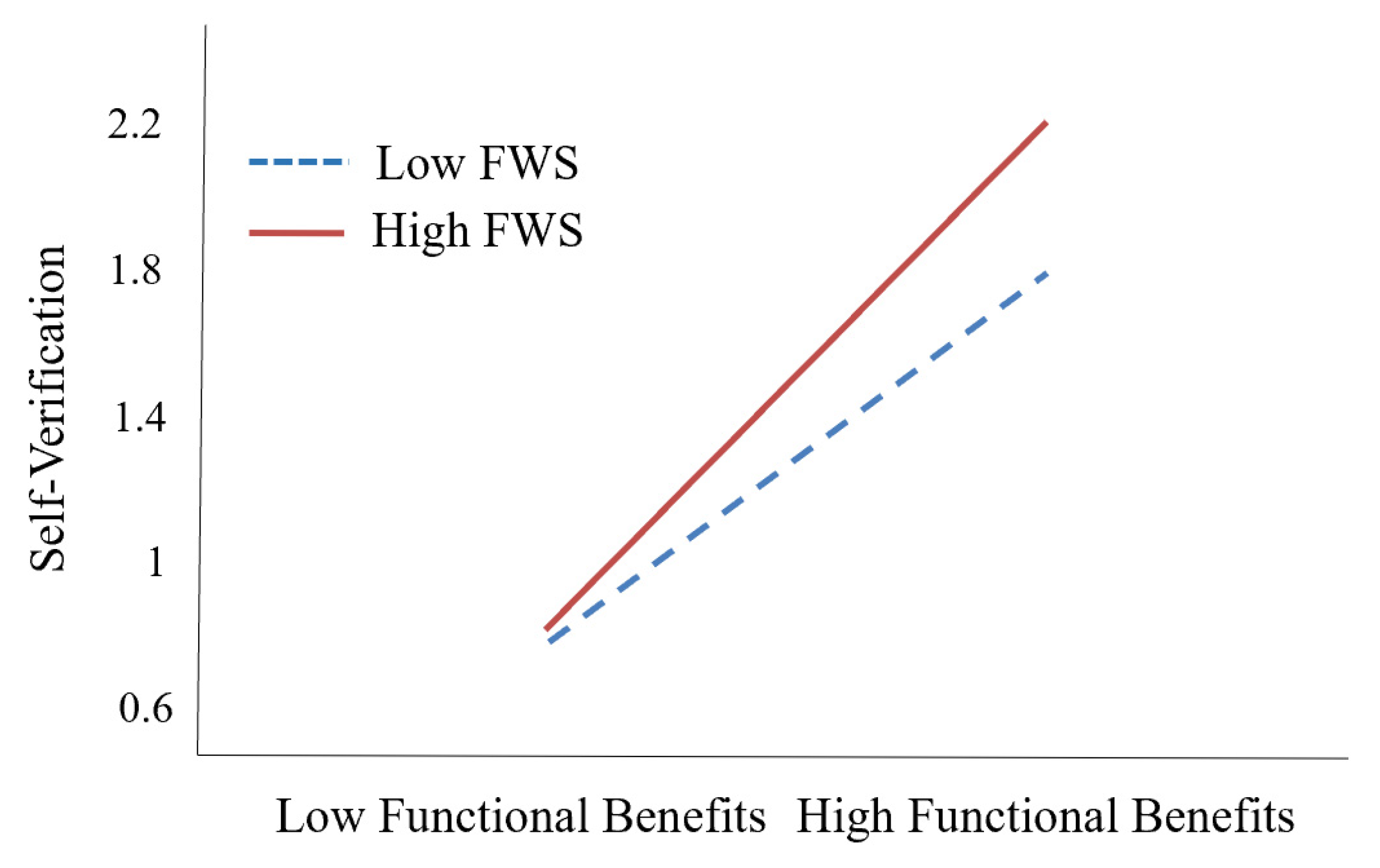

- The moderating role of future work self-salience on the relationship between functional benefits and self-verification

- (4)

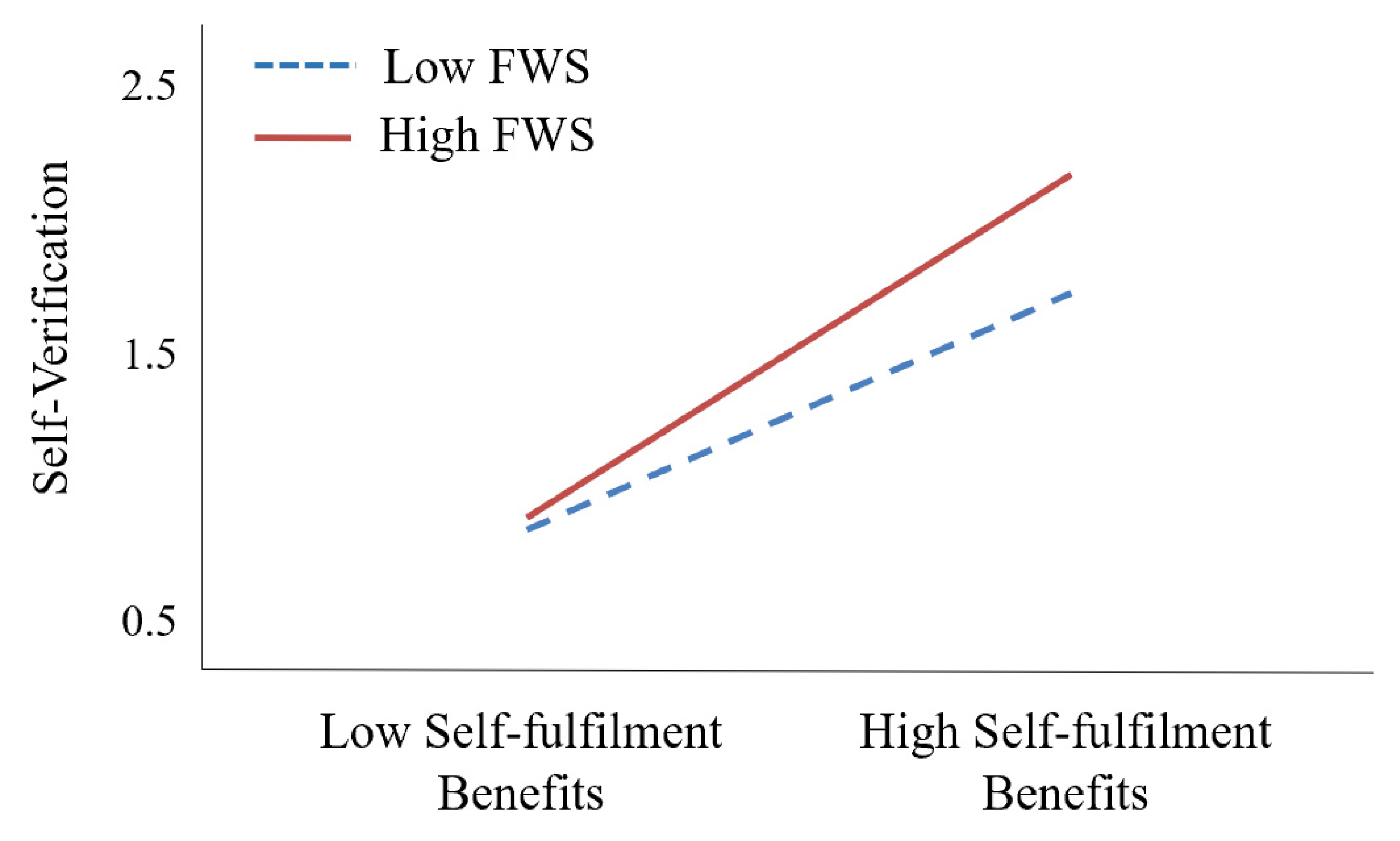

- The moderating role of future work self-salience on the relationship between self-fulfillment benefits and self-verification

6. Discussion

6.1. Theoretical Implications

6.2. Managerial Implications

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Research Questionnaire

- Your age

- Your gender—male, female

- Your education—lower secondary and below, high school, junior college, Undergraduate, Master, Ph.D., Postdoc

- Your career—student, civil servant or institution employee, corporate employee, freelancer, teacher, individual practitioner, or others

- Length of time in the community—under 1 month, 1 month–6 months, 6 months–1 year, 1 year–2 years, 2 years–3 years, 3 years–5 years, more than 5 years

- Variable measurement question design.

| Concept | Title |

|---|---|

| Social Benefits | 1. the social aspect of being in an open innovation community is important to me. |

| 2. I meet like-minded others in the community. | |

| 3. I enjoy the dialogue interactions in the open innovation community. | |

| 4. I enjoy interacting with other open innovation community members. | |

| Economic Benefits | 1. I believe that there are economic benefits to be gained through my contributions in an open innovation community. |

| 2. I expect to receive some financial reward for the act of contributing in an open innovation community. | |

| 3. I would like to be rewarded for my participation in the community (e.g., virtual community coins, brand partnerships). | |

| 4. I will be more willing to contribute on an ongoing basis if I can derive more tangible benefits from my participation in the open innovation community. | |

| Functional Benefits | 1. The information provided by the open innovation community is valuable. |

| 2. The information provided by the open innovation community applies to me. | |

| 3. The open innovation community provides information at an appropriate level of detail. | |

| 4. There are some great features in the community to help me accomplish my tasks. | |

| Self-Fulfilment Benefits | 1.I want to gain a role or reputation as a key opinion leader or key opinion consumer in the community. |

| 2. I want to increase the trust and authority with which I post product-related information about a brand in the community. | |

| 3. I have provided product-related information and advice in reviews posted in the community that has influenced other users’ product use or purchase decisions and enhanced my sense of personal fulfillment. | |

| Self-Verification | 1. I am honest about my habits and personality so that others in the community understand what I can contribute. |

| 2. When meeting new people, I will be truthful about my current abilities even if they may be less than idealized in the minds of others. | |

| 3. Even if people recognize my limitations, I want the community to see what I think I can achieve. | |

| 4. In the community, I try to be honest about my personality and style. | |

| 5. I like to be myself and not pretend to be someone else. | |

| 6. I prefer to let people know the real me in order to not expect too much from me. | |

| 7.I’m willing to gain less to stay in the same community as the people in the community who already know me. | |

| 8. When participating in an online innovation community, I try to find a place where people will accept me. | |

| Future Work Self-Salience | 1. I can conceptualize very early on the level of benefits (social, economic, functional, and self-fulfillment benefits) I can achieve in the future. |

| 2. I build a clear mental picture of the level of benefits I will achieve in the future. | |

| 3. I can get a clear picture of my current level of competence. | |

| 4. I can get a clear picture of how many corresponding benefits I can achieve with my current level of competence. | |

| Continuous Contribution Behavior | 1. I often community-share product/service experiences. |

| 2. I often community post product/service opinions. | |

| 3. I often community-post solutions for products/services. | |

| 4. I often post ideas for new products/services in the community. | |

| 5. I often participate in product/service interactions with others in the community. | |

| 6. I regularly comment on others’ discussions of new product/service ideas in the community. | |

| 7. I often comment on other people’s questions about products/services in the community. |

References

- Enkel, E.; Gassmann, O.; Chesbrough, H. Open R&D and Open Innovation: Exploring the Phenomenon. RD Manag. 2009, 39, 311–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, J.P.; Lee, Y.N.; Nagaoka, S. Openness and innovation in the US: Collaboration form, idea generation and implementation. Res. Policy 2016, 45, 1660–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodie, R.J.; Ilic, A.; Juric, B.; Hollebeek, L. Consumer engagement in a virtual brand community: An exploratory analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, C.; Li, H.; Peng, L.W.; Zhu, L.L. An Evaluation of the Network Influence of Enterprise’s Open InnovationPlatform Based on Link Analysis. Inf. Stud. Theory Appl. 2018, 41, 104–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, C.; Li, H.; Mao, T.T. Study on the Adoption Mechanism of Knowledge Contribution from OpenInnovation Community Users. J. Mod. Inf. 2020, 40, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hippel, E.V. Lead Users: A Source of Novel Product Concepts. Manag. Sci. 1986, 32, 791–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.Y.; Wang, Y.G. Relationship between Customer involvement in Service innovation and Innovation Performance: Literature Review and Model Development from Perspective of Customer Knowledge Transfer. Chin. J. Manag. 2011, 8, 1566–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, A.F.; Shi, K.X.; Yang, Y.J.; Wu, B. Study on the Dynamic Relationship between Users’ Participation and Creative Output of New Product in the Firm-hosted Innovation Community. Technol. Econ. 2020, 39, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahr, D.; Lievens, A. Virtual lead user communities: Drivers of knowledge creation for innovation. Res. Policy 2011, 41, 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.D.; Shen, G.L. Research on the Effect of Sense of Virtual Community on Customer Participation in Value Co-creation—An Empirical Study in Virtual Brand Community. Manag. Rev. 2016, 28, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.Q.; Kraut, R.; Kiesler, S. Applying Common Identity and Bond Theory to Design of Online Communities. Organ. Stud. 2007, 28, 377–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Jin, M.H. The Influence of Incentives Mechanism on Consumers’ Innovative Behavior in Open Innovative Communities. Sci. Sci. Manag. S.&T. 2018, 39, 58–71. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, M.L.; Chi, M.; Han, J.P. Research on the impact of Open Innovative Community Governance Mechanism on User Knowledge Contribution Behavior Based on the Mediating Effect of Virtual Community Sense. Sci. Technol. Prog. Policy 2019, 36, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.L.; Tang, Z.Y.; Zhou, Z.Y.; Yan, J.H.; Xiong, L. Why Users Keep Contributing Knowledge in Q&A Communities?: The Moderating Effect of Level of points. Manag. Rev. 2013, 25, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.T.; Qi, G.J.; Zhang, Y.L.; Liang, Y.K. Research on Continuous Knowledge Sharing Behavior in Open Innovation Communities. Inf. Sci. 2018, 36, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.H.; Li, Y.J.; Zhong, X.J.; Zhai, L. Why users contribute knowledge to online communities: An empirical study of an online social Q&A community. Inf. Manag. 2015, 52, 840–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Wang, L.Y.; Li, Y.; Chen, J. The effect of peer influence on users’ contribution behavior in online innovation community Analysis based on network objective data. Stud. Sci. Sci. 2021, 39, 2294–2304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, K.; Griffin, M.A.; Parker, S.K. Future work selves: How salient hoped-for identities motivate proactive career behaviors. J. Appl. Psychol. 2012, 97, 580–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, X.Q.; Xu, Y.Y. Relationship between Future Work Self Salience and Feedback Seeking Behavior: The impact of Transformational Leadership and Work Engagement. Manag. Rev. 2021, 33, 216–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.M.; Xu, S.H.; Ma, J. Wage Earners or Dream Chasers? Research on the Influence of Meaningfulness of Work on Employee Proactive Behavior from the Perspective of Self-Verification. Bus. Econ. Adm. 2021, 1, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancur, O. The Logic of Collective Action: Public Goods and the Theory of Groups, Second Printing with New Preface and Appendix; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Leong, C.M.L.; Pan, S.L.; Ractham, P.; Kaewkitipong, L. ICT-Enabled Community Empowerment in Crisis Response: Social Media in Thailand Flooding 2011. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2015, 16, 174–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, T. Collective Action on the Internet from the Fan Meizhong Incident. Leg. Syst. Soc. 2008, 34, 213+215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torbert, W. The Power of Balance: Transforming Self, Society, and Scientific Inquiry. Adm. Sci. Q. 1993, 38, 146–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Jeppesen, L. User Toolkits for Innovation: Consumers Support Each Other. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2005, 22, 347–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaewkitipong, L.; Chen, C.C.; Ractham, P. A community-based approach to sharing knowledge before, during, and after crisis events: A case study from Thailand. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 54, 653–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boehm, A.; Staples, L. Empowerment: The Point of View of Consumers. Fam. Soc. 2004, 85, 270–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majchrzak, A.; Wagner, C.; Yates, D. The Impact of Shaping on Knowledge Reuse for Organizational Improvement with Wikis. MIS Q. 2013, 37, 455–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dholakia, U.M.; Bagozzi, R.P.; Pearo, L.K. A social influence model of consumer participation in network- and small-group-based virtual communities. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2003, 21, 241–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dholakia, U.M.; Blazevic, V.; Wiertz, C.; Algesheimer, R. Communal Service Delivery. J. Serv. Res. 2009, 12, 208–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.P.; Zhang, F.L.; Lin, M.F.; Du, H.S. Knowledge sharing among innovative customers in a virtual innovation community: The roles of psychological capital, material reward and reciprocal relationship. Online Inf. Rev. 2017, 41, 691–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Yang, Y.Y.; Shi, W.D. A Predictive Model of the Knowledge-Sharing Intentions of Social Q&A Community Members: A Regression Tree Approach. Int. J. Hum.–Comput. Interact. 2022, 38, 324–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.Y.; Lin, Z.; Nie, J.H. How Personality and Social Capital Affect Knowledge Sharing Intention in Online Health Support Groups?: A Person-Situation Perspective. Int. J. Hum.–Comput. Interact. 2022, 38, 885–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.L.; Lobo, A.; Leckie, C. The role of benefits and transparency in shaping consumers’ green perceived value, self-brand connection and brand loyalty. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2017, 35, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brabham, D.C. Moving the crowd at iStockphoto: The composition of the crowd and motivations for participation in a crowdsourcing application. First Monday 2008, 13, 236–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, K.K.; Chan, A.; Ozer, M. Towards an integrated framework of intrinsic motivators, extrinsic motivators and knowledge sharing. J. Knowl. Manag. 2017, 21, 1486–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.Y.; Zhang, M.J.; Wang, Q.; Ren, Y.; Ma, Y.G.; Ma, S.; Shao, W.; Yin, S.J.; Shi, Z.G. The Research on Purchasing Intention of Fresh Agricultural Products under O2O Mode Based on the Framework of Perceived Benefits-Perceived Risk. China Soft Sci. 2015, 6, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, S.Y.; Sheng, G.H. Research on the Influence Mechanism of the Effect of Centrality of Green Attributes on Consumer Purchase Intention: The Moderating Roleof Product Type and the Mediating Effect of Perceived Benefit. Bus. Econ. Adm. 2021, 4, 52–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, B.T. A comparison of brand personality and brand user-imagery congruence. J. Consum. Mark. 2009, 26, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, F.C.; Jiang, Y.T. Research on Customers’ Value Co-creation Behavior in Virtual Brand Community. Manag. Rev. 2018, 30, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.P.; Zeng, H.; Hao, L.G. An empirical research on the impact of participation atmosphere on online participation intention: From the perspective of social exchange theory. J. Ind. Eng. Eng. Manag. 2022, 36, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, D.; Lin, W.F. Driving Factors for Virtual Brand Community Users’ Behaviors of Participating in Value Co-creation. China Bus. Mark. 2021, 35, 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atuahene-Gima, K.; Slater, S.F.; Olson, E.M. The Contingent Value of Responsive and Proactive Market Orientations for New Product Program Performance. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2005, 22, 464–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linus, D.; Gann, D.M.; Wallin, M.W. How open is innovation? A retrospective and ideas forward. Res. Policy 2021, 50, 104218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christy, M.K.C.; Matthew, K.O.L.; Zach, W.Y.L. Understanding the continuance intention of knowledge sharing in online communities of practice through the post-knowledge-sharing evaluation processes. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2013, 64, 1357–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, H.Y.; Qi, G.J.; Liang, Y.K. Are Actions More Powerful than Words?—User Interaction and Continuous Contribution of User ldea Updates in Open Innovation Community. Manag. Rev. 2022, 34, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Marsden, J.R.; Zhang, Z.J. Theory and Analysis of Company-Sponsored Value Co-Creation. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2014, 29, 141–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, L.; Cheng, H.P. Research on Motivation of Users’ Continuous Knowledge Contribution Behavior in Virtual Knowledge Community Based on Self-determination Theory. Inf. Sci. 2016, 34, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.J.; Ye, J.M.; Zhou, R.; Huang, Y.H.; Huang, D.W. Research on the Factors influencing the Continuous Contribution Behavior of UGC Short Video Users and the Mechanism of Their Role. Libr. Inf. 2022, 5, 31–40. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, Y.F.; Liao, B.; Xu, Y. Research on the impact of Reputation Systems on Knowledge Sharing Activitiesin Social Q&A Community. J. China Soc. Sci. Tech. Inf. 2018, 37, 1154–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosslyn, S.M. Seeing and imagining in the cerebral hemispheres: A computational approach. Psychol. Rev. 1987, 94, 148–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, S.E.; Pham, L.B.; Rivkin, I.D.; Armor, D.A. Harnessing the imagination. Mental simulation, self-regulation, and coping. Am. Psychol. 1998, 53, 429–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, P.P.; Wang, D.; Wang, L. Future work self-salience and an overview of relevant research. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2014, 22–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taber, B.J.; Blankemeyer, M. Future work self and career adaptability in the prediction of proactive career behaviors. J. Vocat. Behav. 2015, 86, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Y.J.; Zhuang, M.K.; Cai, Z.J.; Ding, Y.C.; Wang, Y.; Huang, Z.; Lai, X. Modeling dynamics in career construction: Reciprocal relationship between future work self and career exploration. J. Vocat. Behav. 2017, 101, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swann, W.B.; Read, S.J. Self-verification processes: How we sustain our self-conceptions. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1981, 17, 351–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swann, W.B. Identity negotiation: Where two roads meet. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1987, 53, 1038–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swann, W.B. The self and identity negotiation. Interact. Stud. Soc. Behav. Commun. Biol. Artif. Syst. 2005, 6, 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swann, W.B.; Stein-Seroussi, A.; Giesler, R.B. Why people self-verify. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1992, 62, 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swann, W.B.; Chang-Schneider, C.; Angulo, S. Self-verification in relationships as an adaptive process. In Proceedings of the American Psychological Association, Washington, DC, USA, 3 May 2008; Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org (accessed on 16 December 2022).

- Chen, S.; Chen, K.Y.; Shaw, L. Self-verification motives at the collective level of self-definition. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2004, 86, 77–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Taylor, L.S.; Jeung, K.Y. Collective Self-Verification Among Members of a Naturally Occurring Group: Possible Antecedents and Long-Term Consequences. Basic Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2006, 28, 101–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabian, A.; Russell, J. An Approach to Environmental Psychology; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.H. Research on the Influence of Reward Program Based on SOR Theory on User Online Reviews. Master’s Thesis, University of Technology, Dalian, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.L.; Li, E.Y. Marketing mix, customer value, and customer loyalty in social commerce: A stimulus-organism-response perspective. Internet Res. 2018, 28, 74–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frenzen, J.; Nakamoto, K. Structure, Cooperation, and the Flow of Market Information. J. Consum. Res. 1993, 20, 360–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirtz, J.; Ambtman, A.d.; Bloemer, J.; Horváth, C.; Ramaseshan, B.; Klundert, J.v.d.; Canli, Z.G.; Kandampully, J. Managing brands and customer engagement in online brand communities. J. Serv. Manag. 2013, 24, 223–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Qin, K.; Qin, Q.J. Research on the Influence of Incentive Mechanism on the Knowledge Contribution Effect of Virtual Academic Community. Mod. Inf. 2020, 40, 106–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antikainen, M.J.; Vaataja, H.K. Rewarding in open innovation communities—How to motivate members. Int. J. Entrep. Innov. Manag. 2010, 11, 440–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Lu, Y.B.; Wang, B.; Wu, S.B. The impacts of technological environments and co-creation experiences on customer participation. Inf. Manag. 2015, 52, 468–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.J.; Lee, D.-H.; Taylor, C.R.; Lee, J.-H. Do online brand communities help build and maintain relationships with consumers? A network theory approach. J. Brand Manag. 2012, 19, 213–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, C.E.; Donthu, N. Cultivating Trust and Harvesting Value in Virtual Communities. Manag. Sci. 2008, 54, 113–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeppesen, L.B.; Molin, M.J. Consumers as Co-developers: Learning and Innovation Outside the Firm. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2010, 15, 363–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce, J.L.; Gardner, D.G.; Cummings, L.L.; Dunham, R.B. Organization-Based Self-Esteem: Construct Definition, Measurement, and Validation. Acad. Manag. J. 1989, 32, 622–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swann, W.B.; Wenzlaff, R.M.; Krull, D.S.; Pelham, B.W. Allure of negative feedback: Self-verification strivings among depressed persons. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 1992, 101, 293–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Kim, H.J. Customer mistreatment and service performance: A self-consistency perspective. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 86, 102367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swann, W.B.; Pelham, B. Who Wants Out When the Going Gets Good? Psychological Investment and Preference for Self-Verifying College Roommates. Self Identity 2002, 1, 219–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrauger, J.S. Responses to evaluation as a function of initial self-perceptions. Psychol. Bull. 1975, 82, 581–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhou, Z.E.; Ma, H.Y.; Tang, H.Y. Customer-Initiated Support and Employees’ Proactive Customer Service Performance: A Multilevel Examination of Proactive Motivation as the Mediator. Appl. Psychol. 2020, 70, 1154–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korman, A.K. Toward an hypothesis of work behavior. J. Appl. Psychol. 1970, 54, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swann, W.B. The Trouble with Change: Self-Verification and Allegiance to the Self. Psychol. Sci. 1997, 8, 177–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Liu, C.R.; Yu, W.X.; Li, Y. Research on the Mechanism of How Users Expectancy Disconfirmation Influences the Enterprise-User Value Co-destruction in an Open Innovation Community. Manag. Rev. 2022, 34, 108–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparkman, R.M.; Hair, J.F.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L.; Grablowsky, B.J. Multivariate Data Analysis with Readings. J. Mark. Res. 1979, 16, 437. [Google Scholar]

- de Vries, G.W.; Boon, W.P.; Peine, A. User-led innovation in civic energy communities. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2016, 19, 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhagen, T.; Swen, E.; Feldberg, F.; Merikivi, J. Benefitting from virtual customer environments: An empirical study of customer engagement. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 48, 340–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Ruan, R.B. Research on the Effect of Future Work Self-Salience on Employees’ Innovative Behaviors Based on Regulatory Focus Theory—A Moderated Mediation Model. J. Univ. Electron. Sci. Technol. China 2022, 24, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Lin, Y.Y.; Cui, J.; Wen, Z.L. Future Work Self Salience and Proactive Career Behavior: A Moderated Mediation Model. Psychol. Explor. 2018, 38, 475–480. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, D.Y.; Sun, X.C. Identifying the influencing Factors of Users Information Contribution Behavior on Social Network Sites. Inf. Sci. 2018, 36, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, M.; Liang, S. User recognition mechanism and user contribution behavior in enterprise-hosted online product innovation communities. Nankai Bus. Rev. Int. 2019, 10, 17–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Item | Responses | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 230 | 49.00 |

| Female | 290 | 51.00 | |

| Age | Under 18 years old | 35 | 7.50 |

| 18–25 | 97 | 20.70 | |

| 26–30 | 69 | 14.70 | |

| 31–35 | 93 | 19.80 | |

| 36–40 | 89 | 19.00 | |

| 41–45 | 50 | 10.70 | |

| Over 46 | 36 | 7.70 | |

| Education | Lower secondary and below | 18 | 3.80 |

| High school | 33 | 7.00 | |

| Junior college | 147 | 31.30 | |

| Undergraduate | 102 | 21.70 | |

| Master | 104 | 22.20 | |

| PhD | 45 | 9.60 | |

| Postdoc | 20 | 4.30 | |

| Length of time in the community | Under 1 month | 21 | 4.50 |

| 1 month–6 months | 53 | 11.30 | |

| 6 months–1 year | 54 | 11.50 | |

| 1 year–2 years | 100 | 21.30 | |

| 2 years–3 years | 93 | 19.80 | |

| 3 years–5 years | 99 | 21.10 | |

| More than 5 years | 49 | 10.40 |

| Constructs | Items | Factor Load | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SOB | SOB1 | 0.924 | 0.968 | 0.882 |

| SOB2 | 0.920 | |||

| SOB3 | 0.927 | |||

| SOB4 | 0.985 | |||

| ECB | ECB1 | 0.984 | 0.970 | 0.889 |

| ECB2 | 0.929 | |||

| ECB3 | 0.933 | |||

| ECB4 | 0.924 | |||

| FUB | FUB1 | 0.977 | 0.962 | 0.865 |

| FUB2 | 0.904 | |||

| FUB3 | 0.912 | |||

| FUB4 | 0.926 | |||

| SFB | SFB1 | 0.982 | 0.958 | 0.884 |

| SFB2 | 0.922 | |||

| SFB3 | 0.916 | |||

| SVN | SVN1 | 0.982 | 0.982 | 0.872 |

| SVN2 | 0.935 | |||

| SVN3 | 0.918 | |||

| SVN4 | 0.925 | |||

| SVN5 | 0.921 | |||

| SVN6 | 0.925 | |||

| SVN7 | 0.929 | |||

| SVN8 | 0.935 | |||

| FWS | FWS1 | 0.923 | 0.862 | 0.612 |

| FWS2 | 0.742 | |||

| FWS3 | 0.747 | |||

| FWS4 | 0.697 | |||

| CCB | CCB1 | 0.978 | 0.979 | 0.869 |

| CCB2 | 0.931 | |||

| CCB3 | 0.926 | |||

| CCB4 | 0.934 | |||

| CCB5 | 0.917 | |||

| CCB6 | 0.922 | |||

| CCB7 | 0.917 |

| Construct | FWS | CCB | SVN | SFB | FUB | ECB | SOB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FWS | 0.782 | ||||||

| CCB | 0.475 | 0.932 | |||||

| SVN | 0.379 | 0.511 | 0.934 | ||||

| SFB | 0.505 | 0.555 | 0.560 | 0.940 | |||

| FUB | 0.458 | 0.523 | 0.509 | 0.537 | 0.930 | ||

| ECB | 0.474 | 0.511 | 0.530 | 0.502 | 0.532 | 0.943 | |

| SOB | 0.466 | 0.551 | 0.478 | 0.531 | 0.533 | 0.557 | 0.939 |

| Path | Non-Standardized Coefficient | Standardized Coefficient | Standard Deviation | t-Value | Significance | Hypothesis Testing |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SOB → SVN | 0.100 | 0.118 | 0.035 | 2.864 | ** | PASS |

| ECB → SVN | 0.227 | 0.271 | 0.035 | 6.504 | *** | PASS |

| FUB → SVN | 0.180 | 0.202 | 0.037 | 4.858 | *** | PASS |

| SFB → SVN | 0.304 | 0.342 | 0.037 | 8.140 | *** | PASS |

| SVN → CCB | 0.134 | 0.145 | 0.044 | 3.066 | ** | PASS |

| SOB → CCB | 0.201 | 0.257 | 0.032 | 6.226 | *** | PASS |

| ECB → CCB | 0.116 | 0.150 | 0.033 | 3.485 | *** | PASS |

| FUB → CCB | 0.148 | 0.180 | 0.035 | 4.254 | *** | PASS |

| SFB → CCB | 0.208 | 0.252 | 0.036 | 5.694 | *** | PASS |

| Path | Point Estimate | Product of Coefficients | Bias-Corrected 95% CI | Percentile 95% CI | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S.E. | Z | Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | ||

| SOB → SVN → CCB | 0.013 | 0.008 | 1.625 | 0.002 | 0.036 | 0.000 | 0.033 |

| ECB → SVN → CCB | 0.031 | 0.012 | 2.583 | 0.011 | 0.059 | 0.009 | 0.056 |

| FUB → SVN → CCB | 0.024 | 0.011 | 2.182 | 0.007 | 0.053 | 0.006 | 0.050 |

| SFB → SVN → CCB | 0.041 | 0.016 | 2.563 | 0.013 | 0.078 | 0.012 | 0.076 |

| Variable | Self-Verification | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

| Independent variable | |||

| SOB | 0.467 *** | 0.379 *** | 0.379 *** |

| Moderating variable | |||

| FWS | 0.200 *** | 0.201 *** | |

| Independent variable × Moderating variable | |||

| SOB × FWS | 0.013 | ||

| R2 | 0.218 | 0.250 | 0.251 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.216 | 0.247 | 0.246 |

| F | 130.285 *** | 77.872 *** | 51.850 *** |

| Variable | Self-Verification | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

| Independent variable | |||

| ECB | 0.523 *** | 0.449 *** | 0.464 *** |

| Moderating variable | |||

| FWS | 0.169 *** | 0.171 *** | |

| Independent variable × Moderating variable | |||

| ECB × FWS | 0.091 * | ||

| R2 | 0.274 | 0.297 | 0.305 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.272 | 0.294 | 0.300 |

| F | 176.040 *** | 98.254 *** | 67.875 *** |

| Variable | Self-Verification | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

| Independent variable | |||

| FUB | 0.491 *** | 0.409 *** | 0.421 *** |

| Moderating variable | |||

| FWS | 0.185 *** | 0.193 *** | |

| Independent variable × Moderating variable | |||

| FUB × FWS | 0.111 ** | ||

| R2 | 0.242 | 0.269 | 0.281 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.240 | 0.266 | 0.277 |

| F | 148.865 *** | 85.853 *** | 60.692 *** |

| Variable | Self-Verification | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

| Independent variable | |||

| SFB | 0.544 *** | 0.477 *** | 0.486 *** |

| Moderating variable | |||

| FWS | 0.143 *** | 0.149 *** | |

| Independent variable × Moderating variable | |||

| SFB × FWS | 0.080 * | ||

| R2 | 0.296 | 0.312 | 0.319 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.295 | 0.309 | 0.314 |

| F | 196.750 *** | 105.861 *** | 72.458 *** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sun, Z.; Hu, D.; Lou, X.; Li, Y. The Impact of User Benefits on Continuous Contribution Behavior Based on the Perspective of Stimulus–Organism–Response Theory. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14712. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152014712

Sun Z, Hu D, Lou X, Li Y. The Impact of User Benefits on Continuous Contribution Behavior Based on the Perspective of Stimulus–Organism–Response Theory. Sustainability. 2023; 15(20):14712. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152014712

Chicago/Turabian StyleSun, Zhongyuan, Di Hu, Xuming Lou, and Yucheng Li. 2023. "The Impact of User Benefits on Continuous Contribution Behavior Based on the Perspective of Stimulus–Organism–Response Theory" Sustainability 15, no. 20: 14712. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152014712

APA StyleSun, Z., Hu, D., Lou, X., & Li, Y. (2023). The Impact of User Benefits on Continuous Contribution Behavior Based on the Perspective of Stimulus–Organism–Response Theory. Sustainability, 15(20), 14712. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152014712