Do City Exports Increase City Wages? Empirical Evidence from 286 Chinese Cities

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Mechanism

2.1. Technology-Upgrading Mechanism

2.2. Profit-Sharing Mechanism

3. Model, Data and Variable

3.1. Model

3.1.1. Baseline Estimation Model

3.1.2. Mediating Effect Model

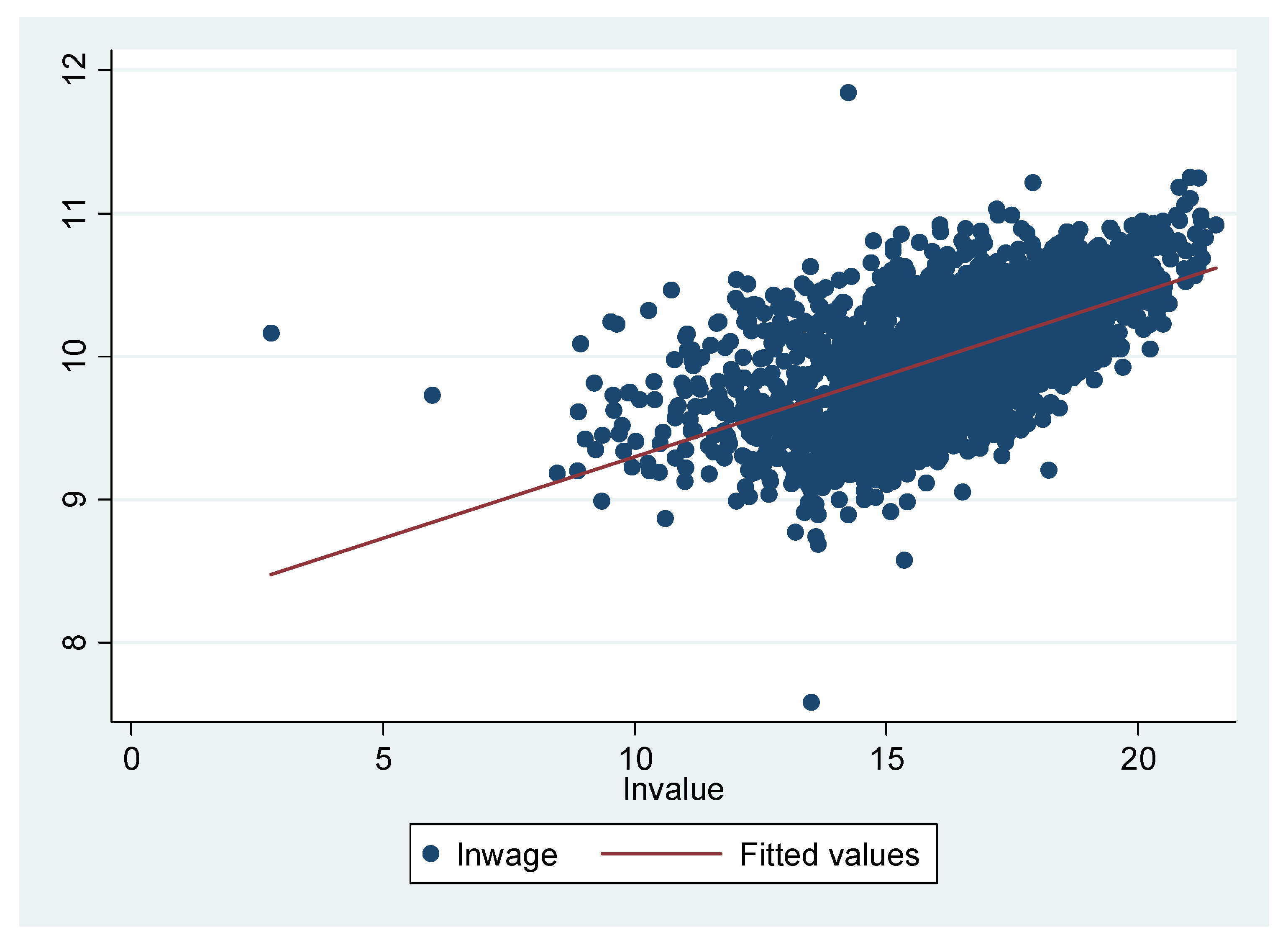

3.2. Data and Variable

4. Empirical Results and Analysis

4.1. Baseline Results

4.2. Robustness Test

4.2.1. Endogenous Problem

4.2.2. Changing Export Metrics

4.2.3. Re-Estimating Mechanism

5. Heterogeneity Analysis

5.1. Location Heterogeneity

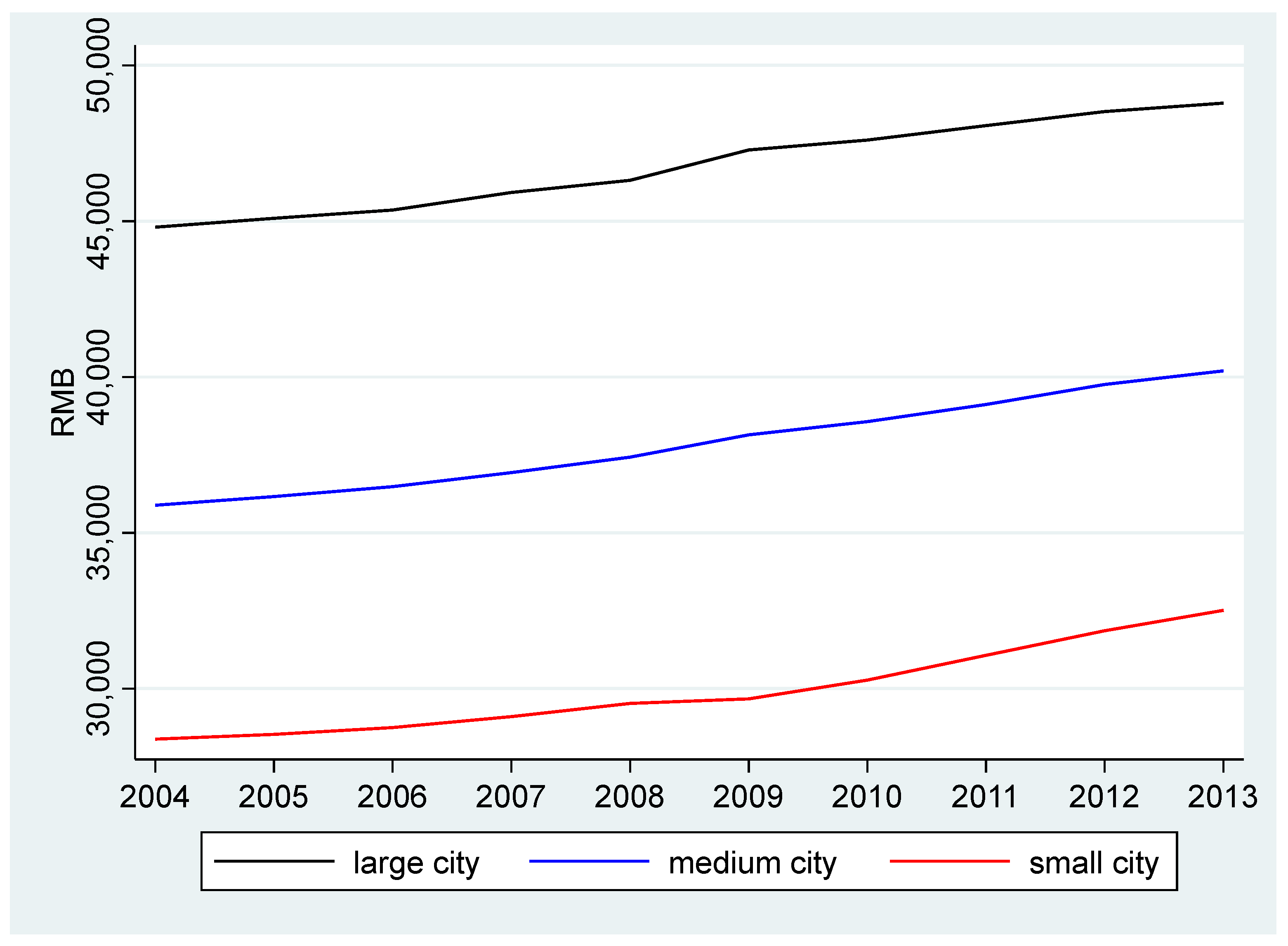

5.2. Scale Heterogeneity

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Henderson, V.; Becker, R. Political Economy of City Sizes and Formation. J. Urban Econ. 2000, 48, 453–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewey, J.; Montes, G. Inter-city wage differentials and intra-city workplace centralization. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 2009, 39, 602–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Roca, J.D.L.; Puga, D. Learning by Working in Big Cities. Rev. Econ. Stud. 2017, 84, 106–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J. Economic Agglomeration, Skill Matching and Wage Premium in Large Cities. Manag. World 2021, 4, 83–97. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, S.H. Urban scale and wage premium: Evidence from China. J. Asia Pac. Econ. 2019, 24, 468–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trana, T.B.; Lab, H.A.; Lea, N.H.M.; Nguyen, K.D. Urban wage premium and informal agglomeration in Vietnam. Eurasian Geogr. Econ. 2022, l63, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brakman, S.; Hu, S.; Van Marrewijk, C. Urban development in China: On the sorting of skills. J. Int. Trade Econ. Dev. 2021, 30, 793–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Combes, P.; Duranton, G.; Gobillon, L.; Roux, S. Sorting and Local Wage and Skill Distributions in France. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 2021, 42, 913–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum-Snow, N.; Pavan, R. Understanding the City Size Wage Gap. Rev. Econ. Stud. 2012, 79, 88–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mion, G.; Naticchioni, P. The Spatial Sorting and Matching of Skills and Firms. Can. J. Econ. 2009, 42, 28–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.F.; Wang, Y.J. Agglomeration and Selection Effect for Wage Gap between Cities in China: Study Using the Unconditional Distribution Feature-Parameter Correspondence Approach. China Ind. Econ. 2018, 12, 60–78. [Google Scholar]

- Andersson, M.; Klaesson, J.; Larsson, J.P. The Sources of the Urban Wage Premium by Worker Skills: Spatial Sorting or Agglomeration Economies. Pap. Reg. Sci. 2014, 93, 727–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, M.; Zhou, H. Which Gains More from Trade Openness: Big or Small Cities? J. Xiamen Univ. 2021, 2, 111–124. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.L. International Trade and China’s Technological Progress: Based on Decomposed Trade Data. Int. Bus. 2019, 3, 46–58. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, J.B.; Zhang, X.; Zhuang, Z.; Cheng, Y. Firm Exports and Innovation: Evidence from Zhongguancun Firm-level Innovation Data. Manag. World 2021, 1, 76–86. [Google Scholar]

- Caldera, A. Innovation and Exporting: Evidence from Spanish Manufacturing Firms. Rev. World Econ. 2010, 146, 657–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roper, S.; Love, J. Innovation and Export Performance: Evidence from the UK and German Manufacturing Plants. Res. Policy 2002, 31, 1087–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrs, L.; Knauth, F. Trade, technology, and the channels of wage inequality. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2021, 131, 103607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.T.; Zhu, S.; Yan, W. Export Technology Upgrading and Income Gap between Urban and Rural Workers. World Econ. Stud. 2021, 3, 30–48. [Google Scholar]

- Kramarz, F. Offshoring, Wages, and Employment: Evidence from Data Matching Imports. Firms and Workers. 2008. Available online: https://academic.oup.com/book/9101/chapter-abstract/155673960?redirectedFrom=fulltext (accessed on 12 November 2022).

- Martins, P.S.; Opromolla, L.D. Exports, Imports and Wages: Evidence from Matched Firm-Worker-Product Panel; IZAD Discussion Paper, No. 4646; IZA: Bonn, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Long, P.D.; Ngoc, P.T.B.; Gorg, H. Trade Liberalization and Labor Market Adjustments: Does Rent Sharing Matter? Emerg. Mark. Financ. Trade 2021, 57, 1828–1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.L.; Wang, Y. Export Growth and Wage Inequality across Firms: Mechanism and Impacts. J. World Econ. 2009, 12, 99–120. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, X.S.; Du, L.; Ma, W.T. A Study on Interest Rate Channel of Monetary Policy in China: Mediation Effect and the Difference between Inside and Outside of the Institutional System. Manag. World 2015, 11, 11–28. [Google Scholar]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The Moderator Mediator Variable Distinction in Social Psychological Research: Conceptual, Strategic and Statistical Considerations. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giannakis, E.; Bruggeman, A. Determinants of Regional Resilience to Economic Crisis: A European Perspective. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2017, 25, 1394–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, X.F.; Huang, J.L.; Huang, Y.H. Have Local Governments Taxed Agglomeration Rents? Manag. World 2012, 2, 19–29. [Google Scholar]

- Kovak, B. Regional Effects of Trade Reform: What is the Correct Measure of Liberalization? Am. Econ. Rev. 2013, 103, 1960–1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaeser, E.L.; Mare, D.C. Cities and Skills. J. Labour Econ. 2001, 19, 316–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Costa, S.; Overman, H.G. The Urban Wage Growth Premium: Sorting or Learning? Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 2014, 48, 168–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |

| OLS | FE | OLS | FE | OLS | FE | OLS | FE | |

| lnvalue | 0.0419 *** (0.0043) | 0.0358 *** (0.0036) | 0.0389 *** (0.0097) | 0.0506 *** (0.0087) | 0.0607 *** (0.0059) | 0.0733 *** (0.0063) | 0.0433 *** (0.0044) | 0.0287 *** (0.0037) |

| lnprod | 0.2196 ** (0.0111) | 0.0419 *** (0.0096) | 0.0432 * (0.0248) | 0.1398 *** (0.0232) | 0.0029 * (0.0153) | 0.0847 *** (0.0167) | 0.2239 *** (0.0109) | 0.0368 *** (0.0098) |

| lndens | 0.0019 * (0.0268) | 0.0704 *** (0.0206) | 0.3404 *** (0.0597) | 0.3571 *** (0.0496) | 0.3063 ** (0.0367) | 0.2796 *** (0.0356) | 0.0030 * (0.0267) | 0.0441 ** (0.0207) |

| lnFDI | −0.0290 *** (−0.0029) | −0.0156 *** (−0.0022) | −0.0025 * (−0.0064) | −0.0129 ** (−0.0053) | −0.0120 *** (−0.0039) | −0.0028 * (−0.0039) | −0.0285 *** (−0.0028) | −0.0163 *** (−0.0022) |

| lninfras | 0.0692 ** (0.0121) | 0.0636 *** (0.0091) | 0.1655 ** (0.0268) | 0.1726 *** (0.0221) | 0.0383 ** (0.0166) | 0.0427 *** (0.0159) | 0.0819 *** (0.0119) | 0.0687 *** (0.0092) |

| lnfixinv | 0.1373 *** (0.0087) | 0.0894 *** (0.0068) | 0.7427 ** (0.0193) | 0.6973 *** (0.0164) | 0.7996 ** (0.0119) | 0.8191 *** (0.0119) | 0.1399 *** (0.0155) | 0.0149 * (0.0125) |

| lnGDP | 0.0905 *** (0.0171) | 0.0811 *** (0.0147) | ||||||

| lnRD | 0.0955 *** (0.0105) | 0.0142 * (0.0106) | ||||||

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| City FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 2065 | 2065 | 2049 | 2049 | 2045 | 2045 | 2034 | 2034 |

| R2 | 0.5787 | 0.4058 | 0.7199 | 0.7578 | 0.8761 | 0.4994 | 0.5973 | 0.4224 |

| Variable | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| lnvalue | 0.1827 *** (0.0240) | 0.4564 *** (0.0601) | 0.0656 ** (0.0269) | 0.2245 *** (0.0309) |

| lnprod | 0.1694 *** (0.0161) | 0.1934 *** (0.0403) | 0.0046 * (0.0179) | 0.1024 *** (0.0215) |

| lndensity | 0.0436 (0.0043) | 0.1905 * (0.1111) | 0.3002 *** (0.0496) | 0.0222 * (0.0315) |

| lnFDI | −0.0436 *** (−0.0043) | −0.0409 *** (−0.0107) | −0.0115 ** (−0.0048) | −0.0119 *** (−0.0035) |

| lninfras | 0.0354 ** (0.0159) | 0.2639 *** (0.0396) | 0.0394 ** (0.0177) | 0.0812 *** (0.0139) |

| lnfixinv | 0.0235 * (0.0218) | 0.4057 *** (0.0543) | 0.5957 *** (0.0246) | 0.1258 *** (0.0179) |

| lnGDP | 0.1423 *** (0.0238) | |||

| lnRD | 0.1067 *** (0.0121) | |||

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| City FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 2042 | 2049 | 2045 | 2034 |

| R2 | 0.3620 | 0.4663 | 0.6541 | 0.4786 |

| Variable | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |

| OLS | FE | OLS | FE | OLS | FE | OLS | FE | |

| lnvalue | 0.0267 *** (0.0060) | 0.0286 *** (0.0049) | 0.0622 *** (0.0132) | 0.0753 *** (0.0117) | 0.0709 *** (0.0082) | 0.0443 *** (0.0087) | 0.0301 *** (0.0060) | 0.0226 *** (0.0048) |

| lnprod | 0.2269 *** (0.0114) | 0.0497 *** (0.0097) | 0.0115 * (0.0248) | 0.1295 *** (0.0231) | 0.0394 ** (0.0155) | 0.1008 *** (0.0172) | 0.2294 *** (0.0111) | 0.0402 *** (0.0098) |

| lndensity | 0.0874 *** (0.0277) | 0.0833 *** (0.0211) | 0.3151 *** (0.0604) | 0.3360 *** (0.0501) | 0.2979 *** (0.0375) | 0.3234 *** (0.0370) | 0.0694 ** (0.0275) | 0.0492 ** (0.0212) |

| lnFDI | −0.0200 *** (−0.0031) | −0.0161 *** (−0.0023) | −0.0042 * (−0.0067) | −0.0071 * (−0.0055) | −0.0061 * (−0.0042) | −0.0039 * (−0.0041) | −0.0199 *** (−0.0030) | −0.0168 *** (−0.0023) |

| lninfras | 0.0849 *** (0.0123) | 0.0661 *** (0.0093) | 0.1692 *** (0.0269) | 0.1765 *** (0.0221) | 0.0387 ** (0.0167) | 0.0349 ** (0.0164) | 0.0998 *** (0.0122) | 0.0095 ** (0.0127) |

| lnfixinv | 0.1844 *** (0.0086) | 0.1016 *** (0.0069) | 0.7439 *** (0.0187) | 0.6943 *** (0.0163) | 0.8142 *** (0.0117) | 0.8524 *** (0.0122) | 0.1484 *** (0.0158) | 0.0095 ** (0.0127) |

| lnGDP | 0.0423 ** (0.0173) | 0.1031 *** (0.0145) | ||||||

| lnRD | 0.0971 *** (0.0107) | 0.0091 * (0.0107) | ||||||

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Ctiy FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 2042 | 2042 | 2049 | 2049 | 2045 | 2045 | 2034 | 2034 |

| R2 | 0.5636 | 0.4624 | 0.7199 | 0.6369 | 0.876 | 0.8961 | 0.5812 | 0.4405 |

| Variable | Technology-Upgrade Mechanism | Profit-Sharing Mechanism | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| OLS | FE | OLS | FE | |

| lnvalue | 0.0522 *** (0.0114) | 0.0146 * (0.0112) | 0.0739 ** (0.0176) | 0.0624 ** (0.0140) |

| ln(value * RD) | 0.0955 *** (0.0105) | 0.0142 * (0.0106) | ||

| ln(value * GDP) | 0.0433 *** (0.0045) | 0.0287 *** (0.0037) | ||

| lnprod | 0.2239 *** (0.0109) | 0.0368 *** (0.0098) | 0.2194 *** (0.0111) | 0.0339 *** (0.0096) |

| lndensity | 0.0031 * (0.0268) | 0.0441 ** (0.0207) | 0.0105 * (0.0272) | 0.0459 *** 0.0206) |

| lnFDI | −0.0285 *** (−0.0028) | −0.0163 *** (−0.0022) | −0.0292 *** (−0.0029) | −0.0162 *** (−0.0022) |

| lninfras | 0.0819 *** (0.0119) | 0.0686 *** (0.0092) | 0.0677 *** (0.0121) | 0.0665 *** (0.0091) |

| lnfixinv | 0.1399 *** (0.0155) | 0.0149 * (0.0125) | 0.1646 *** (0.0156) | 0.0169 * (0.0124) |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| City FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 2034 | 2034 | 2036 | 2036 |

| R2 | 0.5973 | 0.4224 | 0.5808 | 0.4910 |

| Variable | Eastern Cities | Central Cities | Western Cities | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| OLS | FE | OLS | FE | OLS | FE | |

| lnvalue | 0.0830 *** (0.0085) | 0.0261 *** (0.0079) | 0.0289 *** (0.0068) | 0.0189 *** (0.0055) | 0.0201 (0.0140) | 0.0165 (0.0188) |

| lnprod | 0.2991 *** (0.0199) | 0.1043 *** (0.0173) | 0.1937 *** (0.0197) | 0.0412 ** (0.0169) | 0.1716 *** (0.0196) | 0.0323 ** (0.0155) |

| lndensity | 0.0910 *** (0.0305) | 0.0666 *** (0.0236) | 0.2487 *** (0.0603) | 0.0899 ** (0.0451) | 0.1378 (0.1504) | 0.1342 (0.1077) |

| lnfdi | −0.0413 *** (−0.0084) | −0.0052 (−0.0067) | −0.0197 *** (−0.0055) | −0.0056 (−0.0041) | −0.0219 *** (−0.0051) | −0.0113 *** (−0.0037) |

| lninfras | 0.0112 (0.0163) | 0.0022 (0.0123) | 0.1339 *** (0.0226) | 0.1165 *** (0.0166) | 0.1128 *** (0.0266) | 0.1309 *** (0.0190) |

| lnfixinv | 0.0948 *** (0.0141) | 0.0735 *** (0.0109) | 0.1677 *** (0.0149) | 0.1201 *** (0.0114) | 0.1244 *** (0.0202) | 0.0106 (0.0156) |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| City FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 790 | 790 | 819 | 819 | 433 | 433 |

| R2 | 0.6313 | 0.5572 | 0.5646 | 0.4581 | 0.4907 | 0.3671 |

| Variable | Large Cities | Medium Cities | Small Cities | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| OLS | FE | OLS | FE | OLS | FE | |

| lnvalue | 0.0508 *** (0.0062) | 0.0433 *** (0.0054) | 0.0072 (0.0157) | 0.0048 (0.0075) | 0.0091 (0.0084) | 0.0067 (0.0064) |

| lnprod | 0.3505 *** (0.0191) | 0.1159 *** (0.0167) | 0.2339 *** (0.0241) | 0.0146 * (0.0210) | 0.1412 *** (0.0169) | 0.0341 ** (0.0143) |

| lndensity | 0.1559 *** (0.0346) | 0.1799 *** (0.0249) | 0.0486 0.0489 | 0.0102 * (0.0367) | 0.0979 * (0.0552) | 0.0135 (0.0441) |

| lnfdi | −0.0296 *** (−0.0070) | −0.0008 * (−0.0051) | −0.0303 *** (−0.0061) | −0.0139 *** (−0.0046) | −0.0284 *** (−0.0038) | −0.0151 *** (−0.0031) |

| lninfras | 0.0636 *** (0.0212) | 0.0408 *** (0.0149) | 0.0038 (0.0256) | 0.0571 *** (0.0194) | 0.1045 *** (0.0178) | 0.0763 *** (0.0143) |

| lnfixinv | 0.1504 *** (0.0159) | 0.1079 *** (0.0117) | 0.1931 *** (0.0232) | 0.1268 *** (0.0177) | 0.1658 *** (0.0176) | 0.0663 *** (0.0149) |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| City FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 569 | 569 | 661 | 661 | 812 | 812 |

| R2 | 0.6148 | 0.4944 | 0.5059 | 0.3880 | 0.4848 | 0.4458 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhao, C.; Wang, S. Do City Exports Increase City Wages? Empirical Evidence from 286 Chinese Cities. Sustainability 2023, 15, 999. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15020999

Zhao C, Wang S. Do City Exports Increase City Wages? Empirical Evidence from 286 Chinese Cities. Sustainability. 2023; 15(2):999. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15020999

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Chunyan, and Shiping Wang. 2023. "Do City Exports Increase City Wages? Empirical Evidence from 286 Chinese Cities" Sustainability 15, no. 2: 999. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15020999

APA StyleZhao, C., & Wang, S. (2023). Do City Exports Increase City Wages? Empirical Evidence from 286 Chinese Cities. Sustainability, 15(2), 999. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15020999