Abstract

This study aimed to examine the effects of perceived privacy risks and benefits on the online privacy protection behaviors of Chinese teens, with information privacy concerns treated as a mediator variable. The questionnaire survey data (N = 1538) were collected from teens in seven provinces of Mainland China and were analyzed using a structural equation model (SEM). This study found that the effects of teens’ perceived privacy benefits on their information privacy concerns and online privacy protection behaviors are insignificant, but the effects of teens’ perceived privacy risk on their online privacy protection behaviors are significantly positive. Additionally, information privacy concerns significantly mediated the effects of perceived privacy risk on the online privacy protection behaviors of Chinese teens.

1. Introduction

Internet development has brought teens to the digital world since they were born, thus producing a new generation of internet natives. According to the 49th China Statistical Report on Internet Development, as of December 2021, the number of internet users in Mainland China hit 1.032 billion, an increase of 42.96 million compared to that at the end of 2020 [1]. Moreover, there are 183 million minor netizens [1]. The internet has constituted an essential part of teens’ lives, and more and more teens surf the internet using cellphones or PCs. This essential role in teens’ lives comes with benefits and drawbacks. For one thing, teens are given many opportunities such as technological learning and self-expression on the internet. For another, teens are more vulnerable to privacy leaks, pornographic website exposure, the threat of violence, and cyberbullying [2]. A survey revealed that by July 2018, the internet access rate among minors under 18 years old in Mainland China was 93.7%. However, most were not aware of personal information protection. Those under 11 years old know little about privacy settings. Only 25% of those aged 11 to 16 took reasonable actions for online information protection [3]. In this regard, the Chinese government, social organizations, internet groups, and even the research communities have raised concerns about teens’ online privacy protection.

On October 1, 2019, the Protection Regulations of Children’s Personal Data on the Internet, the first online information protection act intended for children, was enacted in Mainland China to protect teens’ online information privacy. However, this act has not considered personal information privacy protection for teens aged 14 to 18. It implies that the personal information privacy of teens aged 14 to 18 will receive the same legal protection as that of adults. On 17 October 2020, the 22nd meeting of the Standing Committee of the 13th National People’s Congress revised the Law of the People’s Republic of China on the Protection of Minors and added a new chapter concerning internet protection, which stipulates that internet service providers should impose a protective limit on the use of any personal information of minors [4]. This act went into effect on 1 June 2021. It suggests that teens’ online privacy security, despite the differences in age groups, will be highlighted and protected by the laws.

A large number of studies on teens’ online privacy have been conducted in different countries, such as Belgium and the U.S., concerning their attitudes towards privacy [5], discussion of social media privacy [6], their online privacy management behavior, and its influencing factors such as gender, age, networked social environment, and parental influence [7]. Moreover, some research has investigated China’s privacy policy [8,9,10]. However, existing studies mainly focus on Western countries. There are fewer studies on privacy protection behaviors in developing countries, and there is especially a lack of quantitative research on the privacy protection of Chinese teens. Teens are considered one of the most vulnerable groups to privacy risks compared to adults [11]. Furthermore, relevant quantitative research on how privacy and disclosure impact privacy protection behaviors from a mediating perspective is also rare.

According to the protection motivation theory (PMT), when people perceive privacy risks and threats, they adopt privacy protection behaviors [12,13]. However, when people perceive privacy benefits that outweigh privacy risks, they may be willing to disclose their privacy in order to obtain the corresponding benefits, which is called the “privacy paradox” [14]. This paper examines the correlations between teens’ perceived privacy risk, perceived disclosure benefits, and online privacy protection behaviors using the structural equation model (SEM) method based on data collected from a questionnaire, with information privacy concerns as a mediator variable. Due to differences in privacy culture in different regions, cultural dimensions are also significantly related to privacy awareness behavior [15]. Therefore, there are crucial empirical and theoretical implications of understanding teens’ privacy behaviors and their influencing factors in non-Western contexts. This study makes two research contributions. First, it provides empirical evidence for the teens’ privacy concept in a non-Western, authoritarian context. Second, this study explains the mechanism and process of the influence of privacy risk perception and benefits perception on protection behavior, thus enriching our understanding of teens’ online privacy protection behaviors.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Protection Motivation Theory and Information Privacy Concerns

For cyber security, many researchers have used the protection motivation theory (PMT) to know what exactly motivates internet users to guard against cyber security threats [16,17]. The PMT guides our theoretical development because it can model interest in protective privacy behaviors in various contexts [18]. This paper also attempted to probe what exactly motivates teens to protect their online information privacy and how teens perceive information privacy concerns. This theoretical framework comprises the information source, perception mediation process, and response mode. It is based on the following hypotheses: protection motivation is derived from the cognitive assessment of adverse incidents and possible events, and a coping response is considered to prevent these events effectively [12]; further, protection motivation may lead to specific behaviors to cope with risk or threat [19]. Suppose this theory is applied in the context of online information privacy. In that case, teens’ concerns about information privacy can be considered as a kind of protection motivation, which can induce them to take appropriate actions to reduce privacy risks. Results have shown that individuals concerned about information privacy are more likely to take appropriate actions to protect online privacy [14]. In this sense, what motivates the protection behavior against information privacy risk may come from the perceived cost of expected behavior and the perceived benefit of risky behavior. In other words, information privacy concerns are considered a critical factor linking privacy awareness and privacy protection behaviors.

The concept and scale of Internet Users’ Information Privacy Concerns (IUIPC), intended to indicate how internet users value personal information, were first put forward by Malhotra et al. (2004) [20]. Precisely speaking, it refers to the public’s view on data inputs, use, and control on the internet. The practice boundaries of information privacy vary across industries, cultures, regulatory provisions, and many other factors. As a result, people often hold different views on the attempt of internet companies to collect and use their personal information [20,21]. Information privacy concerns were initially applied to the e-commerce sector, which was intended to assess how online consumers are concerned about information privacy [22]. Internet development has extended this concept to other areas associated with the internet. For instance, one researcher has recently introduced some scales of this concept to measure online consumers’ information privacy awareness when buying goods [23].

Moreover, another researcher surveyed teen users on the social media platform Facebook in order to assess the effects of their information privacy concerns on trust awareness, risk awareness, and intention to act concerning Facebook [24]. The vital function of information privacy concerns in privacy protection has been observed previously. Information privacy concerns were primarily seen as the factors impacting or being impacted to reveal the correlations between information privacy concerns and behavior or perception. However, the existing literature has not yet looked into the correlations. Of course, previous research noted that information privacy concerns could mediate outcomes between privacy awareness and privacy behaviors [25,26], but the correlations among perceived risk, disclosure benefits, privacy concerns and protection behaviors were not examined in non-western cultures. The concept of information privacy concerns was not measured on a full scale.

The IUIPC framework consists of three dimensions: collection, control, and awareness. The core idea of these three dimensions is that after evaluating the reliability and fairness of collecting private information from enterprises and third-party institutions, network consumers decide whether they can provide personal information to websites. It is similar to the PMT: a behavioral logic for people to take corresponding actions when they face risks to personal information privacy after they have evaluated the social environment.

In addition, while the IUIPC and PMT perspectives provide the rationale for including privacy concerns, perceived risk, and perceived benefits as predictors of online privacy protection behaviors, in the Chinese context, culture is likely to play a crucial role in these relationships. For instance, Krasnova et al. (2012) [27] found that culture impacts people’s privacy disclosure behaviors. They believe that Germany has a more collectivist culture while the United States has a more individualistic one. After comparing Facebook users in the two countries, they concluded that a higher level of individualism facilitates the development of trusting beliefs, thereby stimulating users to reveal information. However, recent studies have focused mainly on western countries and paid less attention to the privacy issues of Chinese teenagers. As China is a typical example of collectivist culture, the privacy interests, risks, and privacy concerns of Chinese teenagers may have different influences on their protection behavior.

Hence, information privacy concerns were considered as the motivation for privacy protection behaviors, and the PMT was applied in the context of China. Information privacy concerns are a mediator variable that can explain the correlation between Chinese teens’ cognitive assessment (or the perceived risk and importance of information privacy leaks) and information privacy protection behaviors [23,25]. In another way, the perceived risk and benefits of online information privacy would impact teens’ information privacy concerns and impact their information privacy protection behaviors.

2.2. Perceived Privacy Risk, Perceived Disclosure Benefits, and Information Privacy Concerns

Perceived risk and benefits constitute an integral part of the tradeoffs in information privacy transactions. Perceived privacy risk is the “expected loss associated with personal information disclosure” [28]. Under certain circumstances, such disclosure may result in an improper use of the disclosed information by other organizations or individuals, which, in turn, causes users to endure uncertain losses [29,30]. According to the theory of rational action, perceived privacy risk is considered a passive perception that impacts personal attitude, and attitude is defined as a kind of acquired tendency [31]. Information privacy concerns are correlated with personal anxiety about privacy [32]. In threatening scenarios, unpleasant feelings (such as anxiety) would intensify due to perceived risk [33].

Consequently, higher risk awareness may lead to more concerns about personal privacy and vice versa [34]. For instance, Dinev and Hart (2006) [30] found that individuals with higher perceived privacy risks would be more concerned about information privacy in the scenarios of online transactions. Seounmi Youn (2009) [26] surveyed teens and found that perceived privacy risk is the most critical factor explaining information privacy concerns. We proposed the first hypothesis:

H1.

Teens with higher perceived privacy risks would be more concerned about information privacy.

Perceived disclosure benefits do not have a specific definition. Milne and Gordon (1993) found that people do not mind providing their personal information when they can obtain certain benefits. These benefits include information, entertainment, or economic value, such as gifts, benefits, or convenient services after providing personal information. Some scholars also thought that most of the related works were performed in the context of online transactions, so the concept of “perceived benefits” is considered a discounted or unpaid service [35]. Following the above works, we define perceived disclosure benefits as the expected benefits of personal information disclosure. On a social media platform, the factors that motivate an individual to disclose information are maintaining and developing relations and feeling the convenience brought by the platform [27]. Disclosure benefits are an intrinsic motivation that positively impacts the intention to disclose personal information required for online transactions [30]. Many researchers have illustrated the social media platform Facebook as an example. They found that undergraduates may provide personal information after receiving benefits from Facebook such as making new social contacts and learning new things [34,36]. In a survey of teens, Youn (2005; 2009) [13,26] found that teens would instead provide personal information to social platforms because they think this will have entertainment, communication, information, and social intercourse benefits. The perceived benefits from information exchange would reduce their privacy concerns. In this regard, we proposed the second hypothesis:

H2.

Teens with higher disclosure benefits would be less concerned about information privacy.

2.3. Perceived Privacy Risk, Perceived Disclosure Benefits, and Privacy Protection Behaviors

Taking the cost and benefit in economics into account, individuals have to trade between benefits and risks due to data disclosure [37]. The typical benefits of sharing personal data include discounted prices for goods and services, better convenience, and facilitated social intercourse [38]. However, data sharing also leads to invisible risks, including all kinds of adverse consequences arising from personal data disclosure. For instance, security defects, identity theft, or accidental use by any third party [39]. The PMT holds that individuals will have different protection motivations and protection behaviors with two options on their hands, partly because the motivation and behaviors meant to guard against risk derive from perceived risk, and partly because the perceived benefits associated with risky behavior reduce personal intention and behavior to guard against risk [12,19].

Researchers have examined the correlation between perceived privacy risk and privacy protection behaviors. For example, individuals may submit falsified data, refuse to buy goods or register information online, or request to have their data deleted to lessen privacy risks [25,40]. In a word, individuals may take appropriate behaviors for privacy protection depending on different levels of perceived risk. The third hypothesis was thus presented:

H3.

Teens with higher perceived privacy risks would be more likely to take appropriate actions to protect online privacy.

Apart from the effects of perceived risk, many researchers found that if individuals consider that the benefits of information disclosure outweigh the risks, they will reduce the intention to protect their privacy and disclose personal information [27,40]. If they perceive that the social or economic gain outweighs the attendant reduction in privacy, they will sacrifice their privacy. Otherwise, they will not [41]. The PMT also states that the perceived benefits associated with risky behavior weaken individuals’ intention to protect themselves from risks [12]. Suppose the PMT is applied in internet scenarios. In that case, the benefits from information disclosure exchange offered by internet companies will discourage the personal motivation to guard against risk and reduce actions taken to protect privacy. We proposed the fourth hypothesis:

H4.

Teens with higher perceived disclosure benefits would be less likely to take appropriate actions to protect online privacy.

2.4. Information Privacy Concerns and Privacy Protection Behaviors

Recent surveys and studies have shown that users’ privacy concerns lead to personal protection responses [13,23,32,42]. What motivates the protective actions is the desire to avoid losses arising from internet companies’ misuse of personal information [43]. Existing studies have supported that information privacy concerns significantly impact tendencies toward personal information disclosure [30], and that internet users with privacy concerns are more likely to refuse to provide their personal information [42]. For example, adult users with greater privacy concerns would be more inclined to take the avoidance strategy on Facebook to protect personal information [35].

However, according to the privacy paradox theory, individual privacy attitudes and actual behaviors may deviate, i.e., internet users are concerned about privacy, but their behaviors do not show these concerns, even to the extent that they will freely give up personal privacy to seek benefits from online activities [14,23,39,44]. Given the paradox between information privacy concerns and privacy protection behaviors, and the fact that information privacy concerns are generally considered the key factor explaining privacy protection behaviors [42], the correlation between individual privacy attitudes and behaviors needs to be further examined. We proposed the fifth hypothesis:

H5.

Teens who are more concerned with information privacy would be more likely to take appropriate actions to protect online privacy.

Available studies have identified factors impacting information privacy concerns and privacy protection behaviors. However, previous studies are inconsistent about what drives information privacy concerns and how this factor impacts individual behaviors [39]. Further, some researchers looked at the relationship between privacy concerns and individual behaviors [26]. However, the variables were measured using summation instead of considering the impact of measurement error. The sample size was small, and the statistical power of the analytical method was insufficient, so there were some flaws [26]. Given this point, the sixth and seventh hypotheses are derived from an integrated survey of the correlations between perceived privacy risk, perceived disclosure benefits, information privacy concerns, and teens’ online privacy protection behaviors, with information privacy concerns treated as a mediator variable:

H6.

Teens’ information privacy concerns mediate the correlation between perceived privacy risk and privacy protection behaviors on the internet.

H7.

Teens’ information privacy concerns can mediate the correlation between perceived disclosure benefits and privacy protection behaviors on the internet.

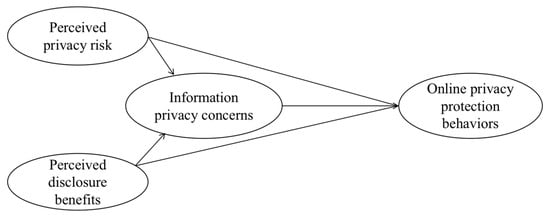

Based on the literature review as summarized above, the theoretical model for this work was proposed as below (Figure 1) [26]:

Figure 1.

Theoretical model.

3. Data

3.1. Sampling

Due to the large gap in the development of the internet economy among different regions in Mainland China, the questionnaire survey took a multi-stage, stratified-cluster random sampling approach. In the first step, according to the administrative division of China, we randomly selected two or three provinces (municipalities or autonomous regions) from the eastern, central, and western regions. In the second step, we selected a capital city from each province (municipality or autonomous region). According to the 2018 provincial GDP ranking, we chose a prefecture-level city or municipal district with a broad economic gap with the capital city. In the third step, we selected a local public secondary school with a medium and high comprehensive strength ranking, and then randomly selected one or two classes from the Senior High School Division. We conducted the questionnaire survey by class. Almost all schools prohibit students from bringing mobile phones and computers onto the campus, so we mainly distributed paper questionnaires by contacting school principals and local volunteers. Additionally, some students filled out electronic questionnaires during the school’s online information courses.

To ensure reliability and validity, we first distributed 400 prediction questionnaires in community libraries, parks, and museums frequented by teenagers in Guangzhou, Guangdong Province. We also conducted in-depth interviews with 14 adolescent respondents. Finally, we revised the questionnaire items according to the interview feedback. The survey began on 20 August 2019 and ended on 15 October 2019. We distributed 2000 questionnaires and recovered 1538, with an effective recovery rate of 76.9%. The scope of this investigation covered the eastern region: Guangzhou (129) and Qingyuan (94) in Guangdong Province, Jinan (88) and Linyi (141) in Shandong Province; the central region: Changsha (161) and Huaihua (157) in Hunan Province, Zhengzhou (104) and Pingdingshan (135) in Henan Province; and the western region: Yongchuan (109) and Beibei (77) in Chongqing, Nanning (57) and Baise (119) in Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, Kunming (83) and Qujing (84) in Yunnan Province. This assures that the selected samples represent the national condition. In addition, all respondents received informed consent from their schools. The statistical description indexes of the samples are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Statistical description of demographic characteristics (N = 1538).

3.2. Measurement

Four latent variables were measured regarding relevant works, including perceived privacy risk, benefits, information privacy concerns, and online privacy protection behaviors. The questionnaire items were designed according to the responses acquired in the pretest stage, the actual situation of internet access, and the environment of Chinese teens. More details are provided below:

Perceived privacy risk. Three items were designed by Youn (2005; 2009) [13,26] for the measurement of perceived privacy risk, ranging from “never” to “very frequent,” and all the items were measured using the forward scoring of the 5-Point Likert Scale. These items were: “When you are asked to provide some personal information online, you will:” (A1) “Clash with parents or teachers;“ (A2) “Feel something negative, like anxiety, concern or regret;“ and (A3) “Get concerned about receiving some spam messages or offensive ads.”

Perceived privacy benefits. Six items were designed by Youn (2005; 2009) [13,26] for the measurement of perceived privacy benefits, ranging from 0 to 1, where “0” means “no,” and “1” means “yes.” These items were: “Have you ever submitted any personal information online in order to meet the following needs?” (B1) “Listen to music, watch a movie or participate in other recreational events;“ (B2) “Do social networking;“ (B3) “read the news;“ (B4) “join a club or association;“ (B5) “take part in a contest;“ (B6) “Create original content on Tik Tok, Weibo, Little Red Book, and other social media platforms.”

Information privacy concerns. Four items were designed by Malhotra et al. (2004) [20] for the measurement of information privacy concerns, ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree,” and all the items were measured using the forward scoring of the 5-Point Likert Scale. These items were: “How do you think of online personal information?” (C1) “User control of personal information is the essential part of user privacy;“ (C2) “Internet companies should disclose how they collect, process, and use data when they gather such information;“ (C3) “I am concerned that internet companies may have collected too much personal information about me;“ (C4) “I may think a little bit whenever internet companies ask me to provide some personal information.”

Online privacy protection behaviors. Three first-order latent variables, including seven items, were designed by Youn (2009) [26], ranging from “never” to “very frequent.“ All the items were measured using the forward scoring of the 5-Point Likert Scale. The first-order latent variables and included items were: “In order to protect online personal information and privacy, you will:” (D1) Take forged actions: (D1a) “Provide falsified personal information;“ and (D1b) “Provide incomplete personal information;“ (D2) Take protective actions: (D2a) “Ask others about what I should do” and (D2b) “Read the privacy notices available on a website;“ (D3) Take inhibitive actions: (D3a) “Set a complex password,” (D3b) “Turn to another website requesting no personal information;“ and (D3c) “Don’t do anything and leave the website.”

The research hypotheses were tested with the statistical analysis software Mplus 7.4 using the SEM method to ensure the conclusion’s reliability to the greatest extent possible. Compared with the traditional statistical analysis method, SEM uses a multi-index measurement system to estimate the latent variables and the measurement errors, which can avoid overestimated results derived from the use of the traditional mean estimation method. Further, SEM can simultaneously support the estimation of latent variables and the parameter estimation of a complex structural model, which can avoid the problem of increasing the likelihood of violating Type I errors when the traditional method is used to perform the multivariate statistical analysis [45].

4. Results

4.1. Measurement Model

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed on four latent variables to construct the measurement model for SEM. It is noteworthy that the perceived privacy benefits were scored 0-1, which means the relationship between items and latent variables is non-linear. This analysis may result in ‘difficulty factors’ when using linear factor analysis [46]. Therefore, perceived privacy benefits were estimated using the weighted least square mean and variance adjusted (WLSMV) method. Other latent variables were estimated using the complete information maximum likelihood (FIML) method, and the measurement model for online privacy protection behaviors was the second-order CFA. According to the results, as listed in Table 2, except for item A3 of perceived privacy risk, which has a normalized factor loading of slightly below 0.45 and squared multiple correlations (SMC) of slightly below 0.2, the normalized factor loading of the corresponding items of the other latent variables is greater than 0.45. This result is highly significant, and the squared multiple correlations of each item are greater than 0.2. According to the results, as listed in Table 3, the composite reliability (CR) of four latent variables is greater than 0.6, the average variance extracted (AVE) of each variable is greater than 0.36, and the arithmetic square root of AVE is greater than the correlation coefficient between latent variables. These results meet the acceptable criteria recommended by researchers [47,48,49,50], which suggests that the measurement of four latent variables has constructive validity.

Table 2.

Confirmatory factor analysis results (N = 1538).

Table 3.

Constructive validity (N = 1538).

4.2. Common Method Bias

Common method bias may arise from data collection using self-reported questionnaire surveys. To address this concern, the latent method factor CFA is used to perform back testing to check whether there is any common method bias, with the test results given in Table 4. None of the model fit indexes of the latent method factor CFA meets the criteria recommended by Kline (2015) [51]; in contrast, the model fit indexes of multifactor correlation CFA meet the acceptable threshold value. In addition, for both models, Δχ2 = 900.423, Δdf = 9, with a significance of difference p < 0.001. Here, this paper calculated corrected χ2 to compare the nested models since the usual χ2 does not follow the central χ2 distribution when estimated using WLSMV. These results indicate that there is no common method bias for the measurement of each latent variable, and the model estimation results will not lead to a mistake.

Table 4.

Common method bias test (N = 1538).

5. Findings

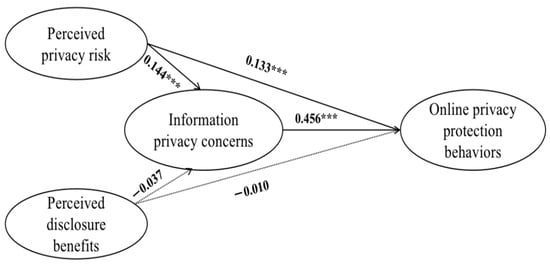

The research hypotheses were tested with the structural model of the SEM model constructed from a theoretical model. According to the results of the path analysis, as given in Figure 2 and Table 5, perceived privacy risk has positive effects on information privacy concerns, indicating that teens with higher perceived privacy risk would be more concerned about online personal privacy, so H1 is established. Furthermore, perceived privacy risk has positive effects on online privacy protection behaviors, indicating that teens with higher perceived privacy risk would be more likely to take appropriate actions to protect online privacy, so H3 is established. In addition, information privacy concerns have positive effects on online privacy protection behaviors, indicating that teens who are more concerned about online privacy would be more likely to take appropriate actions to protect online privacy, so H5 is established. However, the effects of perceived benefits on information privacy concerns and online privacy protection behaviors are insignificant, so H2 and H4 are not established. These results initially suggest that the mediating effect of information privacy concerns may only exist on the path extending from perceived online privacy risk to privacy protection behaviors. Admittedly, this point needs to be further tested hereunder.

Figure 2.

The final model of path analysis. *** p < 0.001.

Table 5.

Results of the path analysis (N = 1538).

Baron and Kenny, Sobel, and other researchers proposed some alternatives to test the mediating effect, but these alternatives are more or less subject to inadequate statistical power [52,53,54]. The Bootstrap method was used to test the mediating effect of information privacy concerns in this study. Common bootstrap methods are generally percentile bootstrap and bias-corrected percentile bootstrap. Available studies have affirmed that the bias-corrected percentile bootstrap method is superior to the percentile bootstrap [55]. Only the results of the bias-corrected percentile bootstrap were reported here. As given in Table 6, the 95% CI of the total effect, indirect effect, and direct effect of the first mediating path do not contain 0. All three effects are significant, indicating that perceived privacy risk can indirectly impact online privacy protection behaviors through information privacy concerns and, thus, implying the mediating effect of information privacy concerns, so H6 is established. In contrast, the 95% CI of the total effect, indirect effect, and direct effect of the second mediating path contain 0 and all three effects are insignificant, indicating that information privacy concerns have no mediating effect on perceived privacy benefits and online privacy protection behaviors, so H7 is not established.

Table 6.

Mediating effect test (N = 1538, Bootstrap samples 5000).

According to the standpoint of Baron and Kenny (1986) [53], information privacy concerns are represented as partial mediation on the first mediating path. However, Hayes (2017) [54] contested that it would be pointless to differentiate between complete mediation and partial mediation. Some other unexamined mediator variables may exist on the path extending from explanatory to explained variables. Furthermore, the determination of complete or partial mediation depends on whether the direct effect is significant. The larger interesting sample size is accompanied by a higher likelihood of significant direct effects. Given this, the empirical results do not intentionally focus on partial mediation here.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

This study examined teens’ exposure to online privacy safety risks and the correlations between teens’ perceived risk and perceived benefits, information privacy concerns, and online privacy protection behaviors arising from privacy disclosure in the context of the Chinese internet based on Rogers’s protection motivation theory. We reached two conclusions: First, the effects of teens’ perceived privacy benefits on their information privacy concerns and online privacy protection behaviors are insignificant, and information privacy concerns do not mediate the relationship between perceived privacy benefits and online privacy protection behaviors. Second, the effects of teens’ perceived privacy risk on their online privacy protection behaviors are significantly positive, and information privacy concerns have mediating effects on perceived privacy risk and protection behaviors.

One contribution of this study is, contrary to previous research conclusions, that it found that perceived disclosure benefits have no significant effect on information privacy concerns and privacy protection behaviors, and information privacy concerns do not mediate between perceived privacy benefits and privacy protection behaviors. This can be attributed to the fact that teens do not place value on whether they can receive the benefits of leaking personal information on the internet or not, which will not increase or lessen their privacy concerns or motivate them to take appropriate actions to protect their privacy. One possible explanation is that the benefits perceived by teens include monetary and nonmonetary benefits. Monetary benefits have been shown to significantly impact information privacy concerns and privacy protection behaviors [56]. In contrast, we examined intangible benefits (e.g., chatting on a social networking app) and found that perceived disclosure benefits have no significant effect on information privacy concerns and privacy protection behaviors. Another possible explanation is that since 2019, many internet service providers have offered a protected mode for teenagers in China, which means that teenagers under 18 years of age can only obtain limited benefits. They cannot give up some of their privacy in exchange for benefits because security settings constrain them from divulging too much private information. This also reflects that in the collectivist cultural environment of China, internet service providers have taken on protecting teenagers cooperatively.

Interestingly, this paper used the measurement criteria for perceived privacy benefits proposed by Youn (2005; 2009) [13,26], but the derived conclusion is very different. Youn argued that according to the PMT, individuals with higher perceived behavior benefits would be more likely to take risky actions. Youn’s conclusion is in line with some explanations of the PMT, but he did not perform a comparative analysis of teens’ perceived privacy benefits and perceived privacy risks. In addition, according to Youn’s results, information privacy concerns only mediate between privacy benefits and some, but not all, privacy protection behaviors. In this study, the mean values of perceived privacy risk and perceived privacy benefits as latent variables were calculated using the mean structure CFA method to be 0.970 and 0.236, respectively. The comparison revealed that teens’ perceived privacy risk is far beyond their perceived benefits. According to the PMT, if people perceive that the effort of taking protective actions is greater than the benefits they will receive, then their intention to take protective actions will be lower or they may even take no action due to the cost of overcoming obstacles. Previous studies have confirmed that when specific protective actions (e.g., using passwords or software protection) are taken, if people perceive a higher cost of a risk response, then their intention to take protective actions will decrease. Our research findings agree well with the “cost-benefit” view as contained in the PMT. In other words, teens’ perceived privacy risk is much greater than their perceived privacy benefits. Perceived disclosure benefits have no significant effect on information privacy concerns and privacy protection behaviors due to the tradeoff between costs and benefits. Many other factors can indeed lead to different conclusions. For example, as Youn mentioned, his sample size was small (N = 144), there is a gap in internet development levels, and China treats the legal and cultural setting of teens’ privacy differently from Western countries.

Another important contribution of this study is that it showed that information privacy concerns can mediate between perceived privacy risk and privacy protection behaviors. Teens with higher perceived privacy risks are more concerned about personal information privacy and then take some actions to prevent those risks and protect their privacy. According to the privacy paradox theory, individuals may be concerned about privacy, but they are reluctant to take appropriate actions to protect privacy when these actions are weighed against seeking benefits from online activities. This paradox between intention and behavior can be attributed to various research approaches and the differences in research contexts [57]. In fact, contrary to the conclusions of studies on adult groups, we found that Chinese teens not only are concerned about online personal privacy but also intend to take appropriate actions to protect their online privacy in order to hedge against risk. This finding partly responds to the privacy paradox that has been recently debated by scholars and reveals different applicable boundaries in the presence of the privacy paradox from the perspective of Chinese teens. It also shows that under the influence of internet risks, the awareness of privacy protection also exists among Chinese teens. This finding has important practical implications. To promote teens’ adoption of privacy protection behaviors, internet platforms and government agencies could vigorously publicize the risks and threats of privacy infringement and improve teens’ privacy risk perception, which will help improve their privacy awareness and encourage them to further adopt privacy protection behaviors.

This study has some limitations. Firstly, perceived privacy benefits were measured in a way that only considered intangible benefits while ignoring monetary benefits. However, monetary benefits have been shown to significantly impact information privacy concerns and privacy protection behaviors, implying some ways to improve the measurement of variables in future studies. Second, to consider the effects of perceived privacy risk and benefits on teens’ online privacy protection behaviors, only information privacy concerns as a mediator variable were examined, to the exclusion of other potential mediator variables. As a result, the complicated mechanism of how perceived privacy risk and perceived privacy benefits would impact privacy protection behaviors in different cultures remains to be discovered.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.Z.; Formal analysis, S.Z.; Investigation, S.Z.; Resources, Y.L.; Writing—original draft, S.Z.; Writing—review & editing, S.Z. and Y.L.; Supervision, Y.L.; Funding acquisition, Y.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The Major Program of National Social Science Fund of China (No: 21&ZD318); Yong River Social Science Planning Youth Project.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Sun Yat-sen University.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest concerning this article’s research, authorship, and publication.

References

- CNNIC. The 47th China Statistical Report on Internet Development. 2021. Available online: http://www.cac.gov.cn/2021-02/03/c_1613923423079314.htm (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- Third, A.; Bellerose, D.; De Oliveira, J.D.; Lala, G.; Theakstone, G. Young and Online: Children’s Perspectives on Life in the Digital Age (The State of the World’s Children 2017 Companion Report); Western Sydney University: Penrith, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China Internet News Center. The Number of Chinese Internet Minor Users Was up to 169 Million, the Internet Availability Rate Reached 93.7%. 2019. Available online: https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1630598311130&wfr=spider&for=pc (accessed on 10 February 2020).

- Xinhuanet. Law of the People’s Republic of China on the Protection of Minors. 2020. Available online: http://www.xinhuanet.com/politics/2020-10/18/c_1126624505.htm (accessed on 12 February 2022).

- Youn, S.; Shin, W. Teens’ responses to Facebook newsfeed advertising: The effects of cognitive appraisal and social influence on privacy concerns and coping strategies. Telemat. Inform. 2019, 38, 30–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crocco, M.S.; Segall, A.; Halvorsen, A.L.; Stamm, A.; Jacobsen, R. “It’s not like they’re selling your data to dangerous people”: Internet privacy, teens, and (non-) controversial public issues. J. Soc. Stud. Res. 2020, 44, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Wolf, R. Contextualizing how teens manage personal and interpersonal privacy on social media. New Media Soc. 2020, 22, 1058–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aho, B.; Duffield, R. Beyond surveillance capitalism: Privacy, regulation and big data in Europe and China. Econ. Soc. 2020, 49, 187–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.L.; Huang, L.; Yan, W.; Wang, X.; Zhang, R. Privacy in AI and the IoT: The privacy concerns of smart speaker users and the Personal Information Protection Law in China. Telecommun. Policy 2022, 46, 102334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddick, C.G.; Zheng, Y. Online Privacy Protection in Chinese City Governments: An Analysis of Privacy Statements. In International E-Government Development; Alcaide Muñoz, L., Rodríguez Bolívar, M., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Alemany, J.; Del Val, E.; Alberola, J.; García-Fornes, A. Enhancing the privacy risk awareness of teenagers in online social networks through soft-paternalism mechanisms. Int. J. Hum. -Comput. Stud. 2019, 129, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, R.W. A protection motivation theory of fear appeals and attitude change. J. Psychol. 1975, 91, 93–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youn, S. Teenagers’ perceptions of online privacy and coping behaviors: A risk-benefit appraisal approach. J. Broadcast. Electron. Media 2005, 49, 86–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, S.; De Jong, M.D. The privacy paradox–Investigating discrepancies between expressed privacy concerns and actual online behavior–A systematic literature review. Telemat. Inform. 2017, 34, 1038–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, P.J.; Spiro, E.S.; Butts, C.T. Thumbs up for privacy?: Differences in online self-disclosure behavior across national cultures. Soc. Sci. Res. 2016, 59, 155–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, H.L.; Sun, J.C.Y. The moderating roles of gender and social norms on the relationship between protection motivation and risky online behavior among in-service teachers. Comput. Educ. 2017, 112, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, H.Y.S.; Jiang, M.; Alhabash, S.; LaRose, R.; Rifon, N.J.; Cotten, S.R. Understanding online safety behaviors: A protection motivation theory perspective. Comput. Secur. 2016, 59, 138–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, R.; Chen, R.; Kim, D.J.; Chen, K. Effectiveness of privacy assurance mechanisms in users’ privacy protection on social networking sites from the perspective of protection motivation theory. Decis. Support Syst. 2020, 135, 113323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddux, J.E.; Rogers, R.W. Protection motivation and self-efficacy: A revised theory of fear appeals and attitude change. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1983, 19, 469–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, N.K.; Kim, S.S.; Agarwal, J. Internet users’ information privacy concerns (IUIPC): The construct, the scale, and a causal model. Inf. Syst. Res. 2004, 15, 336–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, A.J. Relationship marketing in consumer markets: A comparison of managerial and consumer attitudes about information privacy. J. Direct Mark. 1997, 11, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zukowski, T.; Brown, I. Examining the influence of demographic factors on internet users’ information privacy concerns. In Proceedings of the 2007 Annual Research Conference of the South African Institute of Computer Scientists and Information Technologists on IT Research in Developing Countries, Port Elizabeth, South Africa, 2–3 October 2007; pp. 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anic, I.D.; Škare, V.; Milaković, I. The determinants and effects of online privacy concerns in the context of e-commerce. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2019, 36, 100868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusyanti, A.; Puspitasari, D.R.; Catherina, H.P.A.; Sari, Y.A.L. Information privacy concerns on teens as Facebook users in Indonesia. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2017, 124, 632–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirtz, J.; Lwin, M.O.; Williams, J.D. Causes and consequences of consumer online privacy concern. Int. J. Serv. Ind. Manag. 2007, 18, 326–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youn, S. Determinants of online privacy concern and its influence on privacy protection behaviors among young adolescents. J. Consum. Aff. 2009, 43, 389–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasnova, H.; Spiekermann, S.; Koroleva, K.; Hildebrand, T. Online social networks: Why we disclose. J. Inf. Technol. 2010, 25, 109–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Dinev, T.; Smith, J.; Hart, P. Information privacy concerns: Linking individual perceptions with institutional privacy assurances. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2011, 12, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaaya, K.B.; Barhamgi, M.; Chbeir, R.; Arnould, P.; Benslimane, D. Context-aware system for dynamic privacy risk inference: Application to smart iot environments. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2019, 101, 1096–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinev, T.; Hart, P. An extended privacy calculus model for e-commerce transactions. Inf. Syst. Res. 2006, 17, 61–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miltgen, C.L.; Smith, H.J. Exploring information privacy regulation, risks, trust, and behavior. Inf. Manag. 2015, 52, 741–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowling, G.R.; Staelin, R. A model of perceived risk and intended risk-handling activity. J. Consum. Res. 1994, 21, 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.W.; Heo, J. Visiting theories that predict college students’ self-disclosure on Facebook. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 30, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinev, T.; Xu, H.; Smith, J.H.; Hart, P. Information privacy and correlates: An empirical attempt to bridge and distinguish privacy-related concepts. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2013, 22, 295–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dienlin, T.; Metzger, M.J. An extended privacy calculus model for SNSs: Analyzing self-disclosure and self-withdrawal in a representative US sample. J. Comput.-Mediat. Commun. 2016, 21, 368–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, N.; Kwon, O. A privacy-aware feature selection method for solving the personalization–privacy paradox in mobile wellness healthcare services. Expert Syst. Appl. 2015, 42, 2764–2771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Wang, N.; Shen, X.L.; Zhang, J.X. Location information disclosure in location-based social network services: Privacy calculus, benefit structure, and gender differences. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 52, 278–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerber, N.; Gerber, P.; Volkamer, M. Explaining the privacy paradox: A systematic review of literature investigating privacy attitude and behavior. Comput. Secur. 2018, 77, 226–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, K.L.; Teo, H.H.; Lee, S.Y.T. The value of privacy assurance: An exploratory field experiment. Mis Q. 2007, 31, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milne, G.R.; Gordon, M.E. Direct mail privacy-efficiency trade-offs within an implied social contract framework. J. Public Policy Mark. 1993, 12, 206–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.; Park, J.; Jung, Y. The role of privacy fatigue in online privacy behavior. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 81, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Slyke, C.; Shim, J.T.; Johnson, R.; Jiang, J.J. Concern for information privacy and online consumer purchasing. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2006, 7, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Taddicken, M. The ‘privacy paradox’in the social web: The impact of privacy concerns, individual characteristics, and the perceived social relevance on different forms of self-disclosure. J. Comput. -Mediat. Commun. 2014, 19, 248–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollen, K.A.; Long, J.S. (Eds.) Testing Structural Equation Models; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1993; Volume 154. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald, R.P.; Ahlawat, K.S. Difficulty factors in binary data. Br. J. Math. Stat. Psychol. 1974, 27, 82–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. On the evaluation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W. Commentary: Issues and opinion on structural equation modeling. MIS Q. 1998, 22, 7–16. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S.; Ullman, J.B. Using Multivariate Statistics; Pearson: Boston, MA, USA, 2007; Volume 5, pp. 481–498. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 4th ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Commun. Monogr. 2009, 76, 408–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Pituch, K.A.; Stapleton, L.M. The performance of methods to test upper-level mediation in the presence of nonnormal data. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2008, 43, 237–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, E.; Teo, H.H.; Wan, W. Volunteering personal information on the internet: Effects of reputation, privacy notices, and rewards on online consumer behavior. Mark. Lett. 2006, 17, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokolakis, S. Privacy attitudes and privacy behaviour: A review of current research on the privacy paradox phenomenon. Comput. Secur. 2017, 64, 122–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).