The Impact of Local Food Festivals on Rural Areas’ Development

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Festivals Impact

2.2. Classification of Festivals Impact and Functions

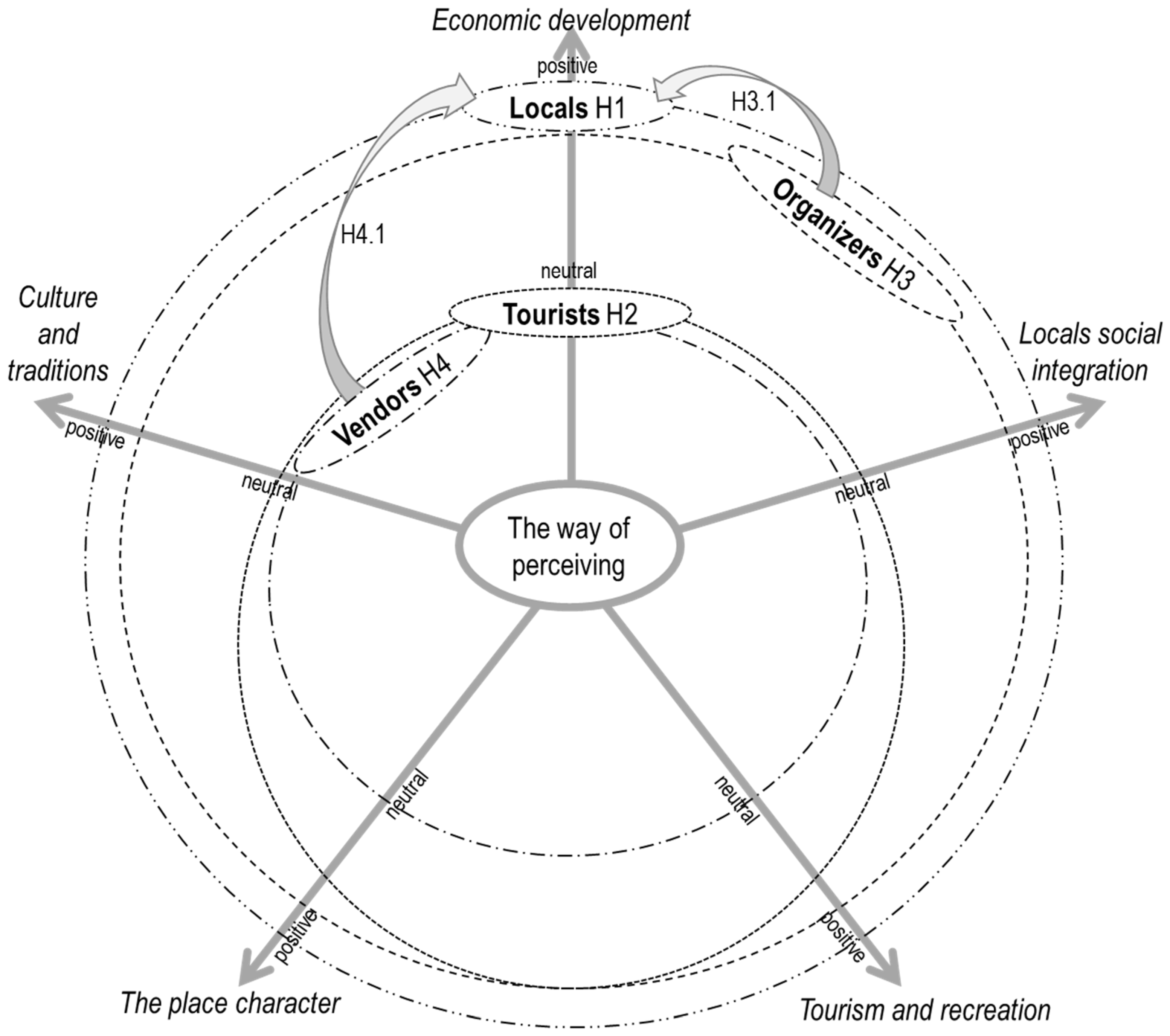

2.3. Stakeholders Perception of Festivals Impact

3. Materials and Methods

4. Research Sample

4.1. Visitors Sample

4.2. Vendors Sample

4.3. Organizer Sample

5. Results

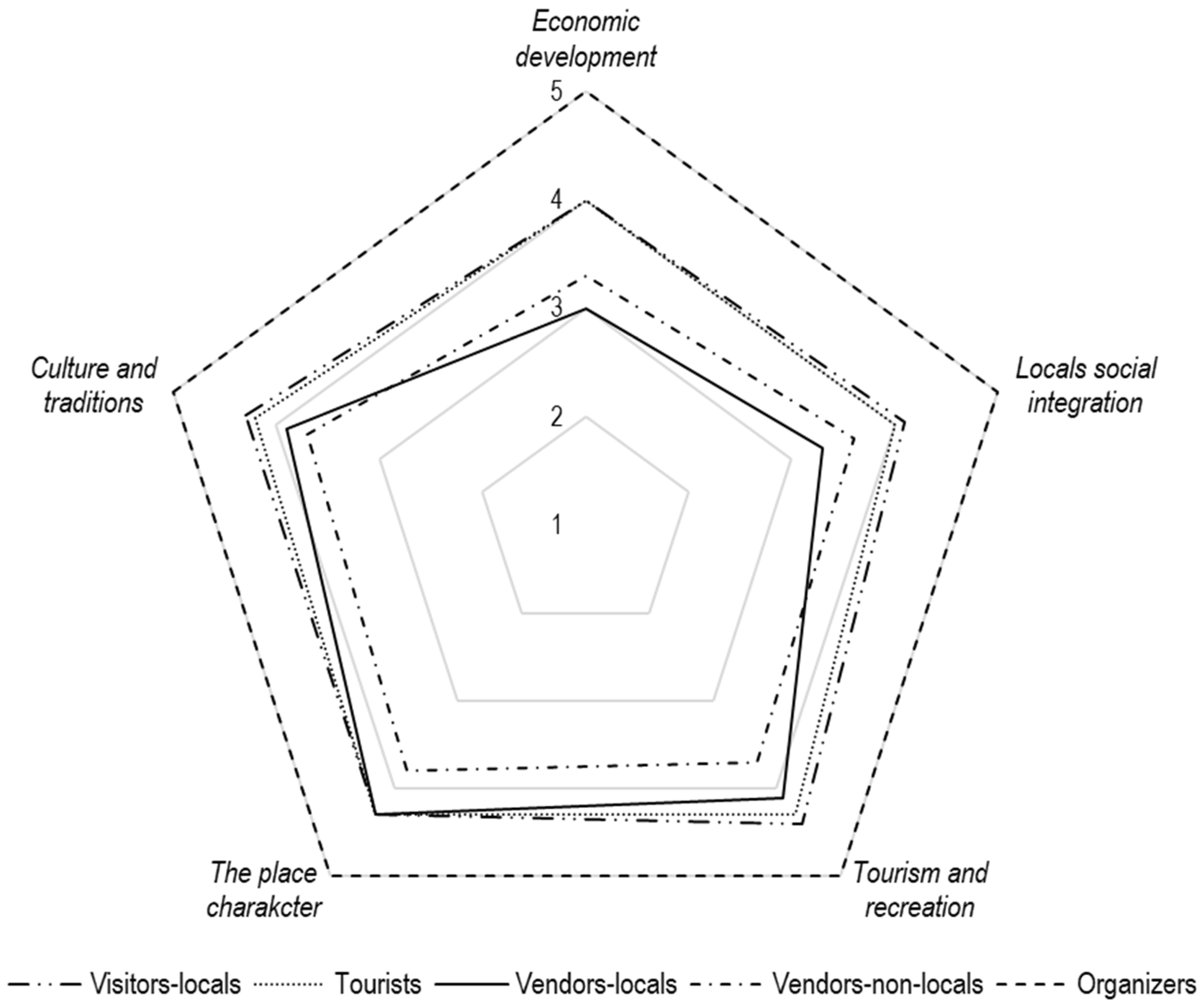

5.1. Visitors

5.2. Vendors

5.3. Organizers

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lee, I.; Arcodia, C. The role of regional food festivals for destination branding. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2011, 13, 355–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwiatkowski, G.; Hjalager, A.-M.; Ossowska, L.; Janiszeska, D.; Kurdyś-Kujawska, A. The entrepreneurial orientation of exhibitors and vendors at food festivals. J. Policy Res. Tour. Leis. Events 2021, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeoman, I.; Mcmahon-Beattie, U.; Findlay, K.; Goh, S.; Tieng, S.; Nhem, S. Future proofing the success of food festivals through determining the drivers of change: A case study of wellington on a plate. Tour. Anal. 2021, 26, 167–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, G.H. Celebrating asparagus: Community and the rationally constructed food festival. J. Am. Cult. 1997, 20, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, T.D.; Lundberg, E. Commensurability and sustainability: Triple impact assessments of a tourism event. Tour. Manag. 2013, 37, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briones Alonso, E.; Cockx, L.; Swinnen, J. Culture and food security. Glob. Food Sec. 2018, 17, 113–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.-H.; Kim, K.-S. Pro-Environmental Intentions among Food Festival Attendees: An Application of the Value-Belief-Norm Model. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjalager, A.-M.; Kwiatkowski, G. Entrepreneurial implications, prospects and dilemmas in rural festivals. J. Rural Stud. 2018, 63, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jong, A.; Varley, P. Food tourism and events as tools for social sustainability? J. Place Manag. Dev. 2018, 11, 277–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tölkes, C.; Butzmann, E. Motivating Pro-Sustainable Behavior: The Potential of Green Events—A Case-Study from the Munich Streetlife Festival. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janiszewska, D.; Ossowska, L.; Kurdyś-Kujawska, A.; Kwiatkowski, G. Relational Food Festivals: Building Space For Multidimensional Collaboration Among Food Producers. In Planning and Managing Sustainability in Tourism; Farmaki, A., Altinay, L., Font, X., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 79–93. [Google Scholar]

- Arcodia, C.; Whitford, M. Festival attendance and the development of social capital. J. Conv. Event Tour. 2006, 8, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derrett, R. Making sense of how festivals demonstrate a community’s sense of place. Event Manag. 2003, 8, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwiatkowski, G.; Oklevik, O.; Hjalager, A.-M.; Maristuen, H. The assemblers of rural festivals: Organizers, visitors and locals. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2019, 28, 255–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folgado-Fernández, J.A.; Di-Clemente, E.; Hernández-Mogollón, J.M. Food Festivals and the Development of Sustainable Destinations. The Case of the Cheese Fair in Trujillo (Spain). Sustainability 2019, 11, 2922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albala, K. Food Fairs and Festivals. In The SAGE Encyclopedia of Food Issues; Albala, K., Ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2015; pp. 565–569. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, T. The strategic use of events within food service: A case study of culinary tourism in Macao. In Proceedings of the First International Conference on Information Science and Engineering, Nanjing, China, 26–28 December 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Mohi, Z.; Wong, J.J. A study of food festival loyalty. J Tour. Hosp. Culin. Arts 2013, 5, 30–43. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, C.M.; Sharples, E. The consumption of experiences or the experience of consumption? An introduction to the tourism of taste. In Food Tourism Around the World: Development, Management and Markets; Hall, C.M., Sharples, E., Mitchell, R., Macionis, N., Cambourne, B., Eds.; Butterworth Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2003; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Pheley, A.M.; Holben, D.H.; Graham, A.S.; Simpson, C. Food Security and Perceptions of Health Status: A Preliminary Study in Rural Appalachia. J. Rural Health 2008, 18, 447–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michel-Villarreal, R.; Hingley, M.; Canavari, M.; Bregoli, I. Sustainability in Alternative Food Networks: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2019, 11, 859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, M.-Y. Primary Metaphors and Multimodal Metaphors of Food: Examples from an Intercultural Food Design Event. Metaphor Symb. 2017, 32, 211–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, R.K.; Antunes, W.; Madslien, E.H.; Belenguer, J.; Gerevini, M.; Perez, T.T.; Prugger, R. From food defence to food supply chain integrity. Br. Food J. 2017, 119, 52–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Shan, Y.; Ling, S. Research on option pricing and coordination mechanism of festival food supply chain. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2022, 81, 101199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscardo, G. Analyzing the role of festivals and events in regional development. Event Manag. 2007, 11, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botti, A.; Monda, A.; Vesci, M. Organizing Festivals, Events and Activities for destination marketing. In Tourism Planning and Destination Marketing; Camilleri, M.A., Ed.; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2019; pp. 203–219. [Google Scholar]

- Getz, D.; Page, S.J. Progress and prospects for event tourism research. Tour. Manag. 2016, 52, 593–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everett, S.; Aitchison, C. The Role of Food Tourism in Sustaining Regional Identity: A Case Study of Cornwall, South West England. J. Sustain. Tour. 2008, 16, 150–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blichfeldt, B.; Halkier, H. Mussels, Tourism and Community Development: A Case Study of Place Branding Through Food Festivals in Rural North Jutland, Denmark. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2014, 22, 1587–1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, M.C.; Paggiaro, A. Investigating the role of festivalscape in culinary tourism: The case of food and wine events. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 1329–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, J.; Wu, H.-C.; Cheng, C.-C. An Empirical Analysis of Synthesizing the Effects of Festival Quality, Emotion, Festival Image and Festival Satisfaction on Festival Loyalty: A Case Study of Macau Food Festival. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2015, 17, 521–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwiatkowski, G.; Kurdyś-Kujawska, A.; Janiszewska, D.; Ossowska, L. Visitors motivation to attend the festival of edible flowers. J Gastron. Tour. 2021, 6, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choo, H.; Park, D.B. Potential for collaboration among agricultural food festivals in Korea for cross-retention of visitors. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 1499–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefrid, M.; Torres, E.N. Hungry for food and community: A study of visitors to food and wine festivals. J. Vacat. Mark. 2022, 28, 366–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, F.; Dedeoglu, B.B.; Okumus, B. Will diners be enticed to be travelers? The role of ethnic food consumption and its antecedents. J. Dest. Mark. Manag. 2022, 23, 100685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baptista Alves, H.M.; Campón Cerro, A.M.; Ferreira Martins, A.V. Impacts of small tourism events on rural places. J. Place Manag. Dev. 2010, 3, 22–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janiszewska, D.; Ossowska, L. Food Festival Exhibitors’ Business Motivation. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salustri, A.; Cocco, V.; Mawroh, H. Mixing culture, food and wine, and rural development to cope with the COVID-19-related crisis of the tourism industry in Italy. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2022, 25, 702–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E.; Widyanta, A. Food tourism experience and changing destination foodscape: An exploratory study of an emerging food destination. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2022, 42, 100964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getz, D. Event tourism: Definition, evolution, and research. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 403–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getz, D. The nature and scope of festival studies. Int. J. Manag. Res. 2010, 5, 1–47. [Google Scholar]

- Einarsen, K.; Mykletun, R.J. Exploring the Success of the Gladmatfestival (The Stavanger Food Festival). Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2009, 9, 225–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boesen, M.; Sundbo, D.; Sundbo, J. Local food and tourism: An entrepreneurial network approach. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2017, 17, 76–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özdemir, B.; Seyitoglu, F. A conceptual study of gastronomical quests of tourist: Authenticity or safety and comfort? Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2017, 23, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antón, C.; Camarero, C.; Laguna, M.; Buhalis, D. Impacts of authenticity, degree of adaptation and cultural contrast on travellers’ memorable gastronomy experiences. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2019, 28, 743–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egresi, I.; Kara, F. Economic and tourism impact of small events: The case of small-scale festivals in Istanbul, Turkey. Stud. UBB Geogr. 2014, 1, 47–64. [Google Scholar]

- Organ, K.; Koenig-Lewis, N.; Palmer, A. Festivals as agents for behaviour change: A study of food festival engagement and subsequent food choices. Tour. Manag. 2015, 48, 84–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakas, F.E.; Duxbury, N.; Remoaldo, P.C.; Matos, O. The social utility of small-scale art festivals with creative tourism in Portugal. Int. J. Event Festiv. Manag. 2019, 10, 248–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baptista Alves, H.M.; Pires Manso, J.R.; da Silva Serrasqueiro Teixeira, Z.M.; Santos Estevão, C.M.; Pinto Nave, A.C. Tourism-based regional development: Boosting and inhibiting factors. Anatolia 2022, 33, 128–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavluković, V.; Armenski, T.; Alcántara-Pilar, J.M. Social impacts of music festivals: Does culture impact locals’ attitude toward events in Serbia and Hungary? Tour. Manag. 2017, 63, 42–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontefrancesco, M. Festive Gastronomy Against Rural Disruption: Food Festivals as a Gastronomic Strategy Against Social-Cultural Marginalization in Northern Italy. In Proceedings of the Dublin Gastronomy Symposium, Dublin, Ireland, 25–29 May 2020; pp. 84–89. [Google Scholar]

- Cudny, W.; Korec, P.; Rouba, R. Resident’s perception of festivals—A case study of Łódź. Sociológia 2012, 44, 704–728. [Google Scholar]

- Yolal, M.; Gursoy, D.; Uysal, M.; Kim, H.; Karacaoglu, S. Impacts of festivals and events on residents’ well-being. Ann. Tour. Res. 2016, 61, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanford, S.; Jung, S. Festival attributes and perceptions: A meta-analysis of relationships with satisfaction and loyalty. Tour. Manag. 2017, 61, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vesci, M.; Botti, A. Festival quality, theory of planned behavior and revisiting intention: Evidence from local and small Italian culinary festivals. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2019, 38, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.H.; Duncan, J.; Chung, B.W. Involvement, Satisfaction, Perceived Value, and Revisit Intention: A Case Study of a Food Festival. J. Culin. Sci. Technol. 2015, 13, 133–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.G.; Suh, B.W.; Eves, A. The relationships between food-related personality traits, satisfaction, and loyalty among visitors attending food events and festivals. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2010, 29, 216–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhartanto, D.; Brien, A.; Primiana, I.; Wibisono, N.; Triyuni, N.N. Tourist loyalty in creative tourism: The role of experience quality, value, satisfaction, and motivation. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 23, 867–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choo, H.; Park, D.-B.; Petrick, J.F. Festival tourists’ loyalty: The role of involvement in local food festivals. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2022, 50, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruger, M. Festival loyalty to a South African literary arts festival: Action speaks louder than words. Int. J. Event Festiv. Manag. 2019, 10, 189–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigolo, V.; Bonfanti, A.; Brunetti, F. The effect of performance quality and customer education on attitudinal loyalty: A cross-country study of opera festival attendees. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2019, 48, 1272–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gursoy, D.; Kim, K.; Uysal, M. Perceived impacts of festivals and special events by organizers: An extension and validation. Tour. Manag. 2004, 25, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tregear, A. Lifestyle, growth, or community involvement? The balance of goals of UK artisan food producers. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2005, 17, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pret, T.; Cogan, A. Artisan entrepreneurship: A systematic literature review and research agenda. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2019, 25, 592–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flyvbjerg, B. Five Misunderstandings About Case-Study Research. Qual. Inq. 2006, 12, 219–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starman, A.B. The case study as a type of qualitative research. J. Contemp. Educ. Stud. 2013, 1, 28–43. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric Theory, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Schräpler, J.-P.; Schupp, J.; Wagner, G.G. Changing from PAPI to CAPI: Introducing CAPI in a Longitudinal Study. J. Off. Stat. 2010, 26, 233–269. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, T.W.; Kim, J.A. Review of Survey Data-Collection Modes: With a Focus on Computerizations. Sociol. Theory Method 2015, 30, 185–200. [Google Scholar]

- Books, M. In-Depth Interviewing as Qualitative Investigation. In Classroom Teachers and Classroom Research; Griffee, D.T., Nunan, D., Eds.; Japan Association for Language Teaching: Tokyo, Japan, 1997; pp. 137–146. [Google Scholar]

- Brounéus, K. In-depth Interviewing: The process, skill and ethics of interviews in peace research. In Understanding Peace Research: Methods and Challenges; Höglund, K., Öberg, M., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 130–145. [Google Scholar]

| Category of Stakeholders | Visitors | Vendors | Organizers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Research method | A questionnaire survey was conducted. The questions were closed, and a five-point Likert scale was used to answer. Additionally, the researchers interviewed the visitors. | Semi-structured interviews were conducted. The main questions were closed with the Likert scale. The interviews provided additional information. | An in-depth interview was conducted. |

| Number of participants | 210 | 12 | 1 |

| Characteristic | In % |

|---|---|

| Place of residence | |

| Locals | 41.14 |

| Tourists | 52.86 |

| Education | |

| Higher | 55.24 |

| Secondary | 30.48 |

| Vocational | 9.05 |

| Other | 5.24 |

| Age | |

| Up to 25 years | 10.48 |

| 26–35 | 17.14 |

| 36–45 | 19.05 |

| 46–55 | 18.57 |

| 56 or older | 26.67 |

| Characteristic | In % |

|---|---|

| Duration of business activity (in years) | |

| 1–3 | 25.00 |

| 4–8 | 16.67 |

| 9–13 | 33.33 |

| 14 and more | 25.00 |

| Sales range | |

| Local | 15.39 |

| Regional | 38.46 |

| National | 46.15 |

| International | 0.00 |

| Average annual number of festivals attended | |

| 1–8 | 41.67 |

| 9–13 | 16.67 |

| 14–18 | 25.00 |

| 19 and more | 16.67 |

| Distance of place of residence from the festival site (in km) | |

| 0–50 | 25.00 |

| 50–130 | 25.00 |

| 130–210 | 33.33 |

| 210 and more | 16.67 |

| Specification | Visitors (Total) | Locals | Tourists |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average responses * | |||

| Economic development | |||

| Local business development | 4.31 | 4.32 | 4.29 |

| Income | 3.81 | 3.81 | 3.80 |

| Employment opportunities | 3.91 | 3.90 | 3.93 |

| Culture and tradition | |||

| Return to culinary traditions | 4.20 | 4.20 | 4.21 |

| Care for local heritage | 4.29 | 4.36 | 4.22 |

| Local products promotion | 4.31 | 4.34 | 4.28 |

| Social integration | |||

| Increased integration | 4.09 | 4.16 | 4.03 |

| Locals’ involvement | 4.09 | 4.03 | 4.13 |

| Residents’ cooperation with common goals | 4.03 | 4.07 | 3.98 |

| Character of the place | |||

| Uniqueness | 4.29 | 4.29 | 4.29 |

| Promotion | 4.41 | 4.46 | 4.38 |

| Identity enhancement | 4.18 | 4.18 | 4.17 |

| Tourism and recreation | |||

| Creating a tourist attraction | 4.43 | 4.50 a | 4.37 a |

| Tourist influx | 4.32 | 4.35 | 4.31 |

| Recreation for locals | 4.20 | 4.26 | 4.14 |

| Specification | Vendors (Total) | Local Vendors | Nonlocal Vendors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average responses * | |||

| Economic development | |||

| Local business development | 3.83 | 3.75 | 3.88 |

| Income | 2.67 | 2.25 | 2.88 |

| Employment opportunities | 3.00 | 3.00 | 3.00 |

| Culture and tradition | |||

| Return to culinary traditions | 3.67 | 3.50 | 3.75 |

| Care for local heritage | 3.75 | 4.00 | 3.63 |

| Local products promotion | 3.92 | 4.25 | 3.75 |

| Social integration | |||

| Increased integration | 3.67 | 3.50 | 3.75 |

| Locals’ involvement | 3.42 | 3.25 | 3.50 |

| Residents’ cooperation with common goals | 3.42 | 3.25 | 3.50 |

| Character of the place | |||

| Uniqueness | 3.75 | 4.00 | 3.63 |

| Promotion | 4.33 | 4.75 | 4.13 |

| Identity enhancement | 3.75 | 4.00 | 3.63 |

| Tourism and recreation | |||

| Creating a tourist attraction | 3.92 | 4.25 | 3.75 |

| Tourist influx | 4.00 | 4.50 | 3.75 |

| Recreation for locals | 3.58 | 3.50 | 3.63 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ossowska, L.; Janiszewska, D.; Kwiatkowski, G.; Kloskowski, D. The Impact of Local Food Festivals on Rural Areas’ Development. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1447. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15021447

Ossowska L, Janiszewska D, Kwiatkowski G, Kloskowski D. The Impact of Local Food Festivals on Rural Areas’ Development. Sustainability. 2023; 15(2):1447. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15021447

Chicago/Turabian StyleOssowska, Luiza, Dorota Janiszewska, Gregory Kwiatkowski, and Dariusz Kloskowski. 2023. "The Impact of Local Food Festivals on Rural Areas’ Development" Sustainability 15, no. 2: 1447. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15021447

APA StyleOssowska, L., Janiszewska, D., Kwiatkowski, G., & Kloskowski, D. (2023). The Impact of Local Food Festivals on Rural Areas’ Development. Sustainability, 15(2), 1447. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15021447