Embedded Coexistence: Social Adaptation of Chinese Female White-Collar Workers in Japan

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Data and Methodology

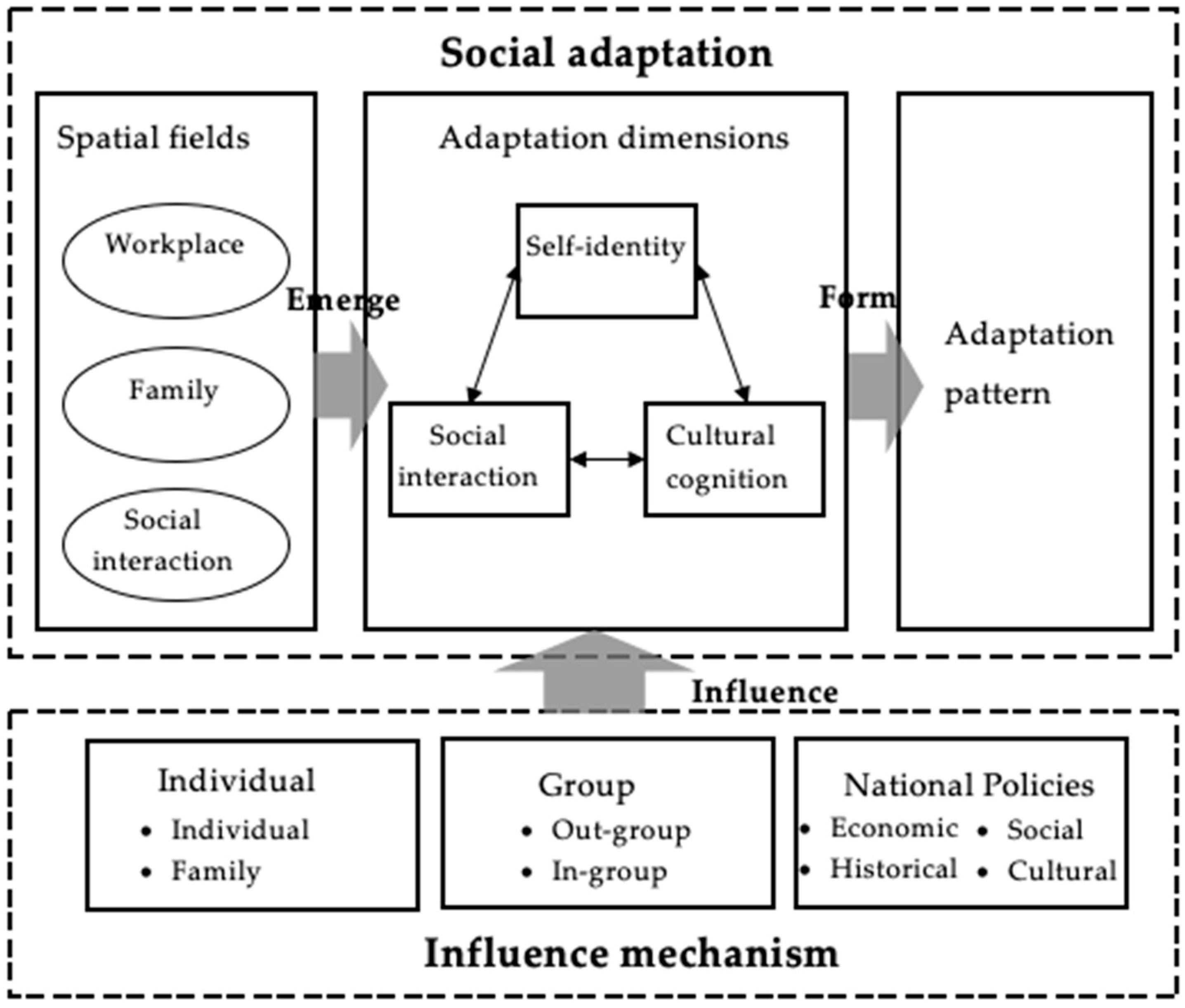

2.1. Concept Definition and Analytical Framework

2.2. Data and Methods

3. Findings

3.1. Selective Social Adaptation

3.1.1. Self-Identity: Permanent Sojourners

“What is this place for me?” “Do I want to stay here for the rest of my life?” I often ask myself these questions. I don’t have to hang in a tree like the Japanese. I think this kind of outsider mentality sometimes has its advantages. When problems crop up, you are not so torn. Japan is not my home field, after all. I will return to China when I am old, but maybe I don’t need to wait to be old. We will go back to China when our children go to college.(L.W.J., 32 years old)

I’m a foreigner, so the company doesn’t ask me to do as much (as the Japanese do).(T.T., 32 years old)

I’m a foreigner, so I’m different. Alternatively, maybe the company recruited me to show off my personality and didn’t want me to be like the Japanese.(L.H.M., 29 years old)

3.1.2. Cultural Cognition: Eclectic but Inclined towards Chinese Culture

I went to China on a business trip with my Japanese manager. A Chinese state-owned enterprise manager said he would arrive at 10:00, but actually came at almost 11:00. The Japanese manager said, “I’m used to it. In China, when you say ‘start at 10:00′, 9:00 to 11:00 is considered 10:00”. I said to him, “Not all Chinese are like that. I’m never late”. He said, “That’s because you’ve been in Japan too long”. In Japan, whether it’s a meeting with a tutor or a client, you have to arrive five minutes early, and you can’t be too early lest you put pressure on people. But it’s impossible to be late. Perhaps he was right, and I developed the habit of keeping time in Japan.(M.M., 31 years old)

I regret that our children must first learn Japanese geography and history when they start school. The culture of China is thousands of years old and profound, and it is a pity that they do not have a Chinese cultural environment.(H.M.,33 years old)

3.1.3. Social Interaction: Multiple Contacts across Ethnic Groups

You can talk about work, TV shows, food, and Chinese and Japanese culture with Japanese, but for relatively private content, like my relationship with my mother-in-law or a couple’s quarrel, I will talk with Chinese. Because of cultural differences, she may not understand what you mean. Additionally, although there are friends we have known for more than ten years, we always feel a sense of distance from them and they didn’t open their hearts to you either.(H.X., 41 years old)

3.2. Formation and Maintenance of Social Adaptation

3.2.1. Individual Rational Choice

My husband and I are both Chinese, I have a permanent residency visa and my husband has a highly-skilled professional visa. Considering the future education of our child, we gave birth in the United States and our baby is a dual U.S. and Chinese citizen and has a Japanese permanent residency now.(D.X.M., 34 years old)

3.2.2. Mutual Pressure of the In-Group and Out-Group

Alienation of the Out-Group

The Japanese who I worked together with for 8–10 h a day and had lunch with together before have never been in touch since I resigned, including some Japanese female colleagues who used to go to parties with me or go shopping together. I thought I was getting along with them more deeply, but it is not real.(Z.X.,29 years old)

When we went shopping together, no matter what you showed her, she would say “kawaii” (cute), and no matter which dresses I chose, she just would describe the advantages. I felt bored after going out together several times.(L.X.S.,27 years old)

Japanese mothers are always surprised by my education and job when I talk with them. Nevertheless, I am surrounded by such Chinese. This means that the Japanese don’t look up to us immigrants at all but still have a condescending attitude.(X.L., 36 years old)

Incomprehension of the In-Group

Every year when I go home to visit my relatives, I am asked how much I earn. A relative said acidly, “That is how much you make overseas? It’s not much more than our child in Beijing”. I was very uncomfortable. In Japan, people have a sense of boundaries, so they don’t ask that question, and even if they asked, they wouldn’t say that.(W.Z.Y.,34 years old)

5 or 6 years ago, I took a business trip from Japan to Taiyuan (China) with a Japanese manager. We took a taxi from the development zone to the airport when we left. When we arrived at the airport, the driver gestured at 80 yuan with his hand and took out an expired invoice. At that time, I said it was incorrect in Chinese, and the driver said, “So you are Chinese?” I gave him money at the actual price of the proper invoice, and he said, “So stingy even after coming from abroad”.(L.C.Q,33 years old)

3.2.3. National Policies and Historical Issues

Not only do I not want to change (my nationality), but my parents also disagree. When I left China, my parents repeatedly instructed me “absolutely not to change nationality to Japan”.(H.M., 33 years old)

About the Sino-Japanese war, Japanese history textbooks are written to describe a process of “the enlightenment of civilisation from ignorance”. I told my son that aggression is the true motivation for the war no matter how it is embellished. When my children grow up, I will take them to the Nanjing Massacre Memorial Hall.(T.H.Y, 41 years old)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Herrera, G. Gender and international migration: Contributions and cross-fertilizations. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2013, 39, 471–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kõu, A.; Bailey, A. “Some people expect women should always be dependent”: Indian women’s experiences as highly skilled migrants. Geoforum 2017, 85, 178–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Ramis Ferrer, B.; Luis Martinez Lastra, J. Building University-Industry Co-Innovation Networks in Transnational Innovation Ecosystems: Towards a Transdisciplinary Approach of Integrating Social Sciences and Artificial Intelligence. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Organization for Migration (IOM). Harnessing Knowledge on the Migration of Highly Skilled Women. Available online: https://publications.iom.int/system/files/pdf/iom_oecd_gender.pdf (accessed on 31 October 2022).

- Sekiguchi, T.; Froese, F.J.; Iguchi, C. International human resource management of Japanese multinational corporations: Challenges and future directions. Asian Bus. Manag. 2016, 15, 83–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oishi, N. Skilled or Unskilled?: The Reconfiguration of Migration Policies in Japan. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2021, 47, 2252–2269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conrad, H.; Meyer-Ohle, H. Overcoming the ethnocentric firm? Foreign fresh university graduate employment in Japa-n as a new international human resource development method. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2019, 30, 2525–2543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hof, H. “Worklife pathways” to Singapore and Japan: Gender and racial dynamics in Europeans’ mobility to Asia. Soc. Sci. Jpn. J. 2018, 21, 45–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hof, H. The Eurostars go global: Young Europeans’ migration to Asia for distinction and alternative life paths. Mobilities 2019, 14, 923–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L. Labor Segmentation and the Outmigration Intention of Highly Skilled Foreign Workers: Evidence from Asian-Born Foreign Workers in Japan; Research Institute of Economy Trade and Industry: Tokyo, Japan, 2019; Available online: https://www.rieti.go.jp/jp/publications/dp/18e028.pdf (accessed on 31 October 2022).

- Japan Student Services Organization. Survey on the Status of Foreign Students. 2022. Available online: https://www.studyinjapan.go.jp/ja/statistics/zaiseki/index.html (accessed on 31 October 2022).

- Hof, H.; Tseng, Y.F. When “global talents” struggle to become local workers: The new face of skilled migration to corporate Japan. Asian Pac. Migr. J. 2020, 29, 511–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjaastad, L.A. The Costs and Returns of Human Migration. J. Political Econ. 1962, 70, 80–93. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1829105 (accessed on 31 October 2022). [CrossRef]

- Todaro, M.P. A Model of Labor Migration and Urban Unemployment in Less Developed Countries. Am. Econ. Rev. 1969, 59, 138–148. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, J.E. Differential migration, networks, information and risk. Migr. Hum. Cap. Dev. 1986, 4, 147–171. [Google Scholar]

- Stark, O.; Bloom, D.E. The new economics of labor migration. Am. Econ. Rev. 1985, 75, 173–178. [Google Scholar]

- Doeringer, P.B.; Piore, M.J. Internal Labor Markets and Manpower Analysis: With a New Introduction, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Portes, A.; Walton, J. Labor, Class, and the International System; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.H. Study on Family Strategies of Married Women Working in Japan under Gender Perspective. J. Youth Stud. 2015, 06, 82–90. [Google Scholar]

- Nomura, S. Chinese in Japan; Kodansha: Tokyo, Japan, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Saihan, J.N. International in the Global Immigration Era: Chinese Wives Setting in Rural Japan; Keiso-shobo: Tokyo, Japan, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Tseng, Y.F. Becoming global talent? Taiwanese white-collar migrants in Japan. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2021, 47, 2288–2304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu-Farrer, G. “I am the Only Woman in Suits”: Chinese Immigrants and Gendered Careers in corporate Japan. J. Asia-Pac. Stud. (Waseda Univ.) 2009, 13, 37–48. [Google Scholar]

- Park, R.E. Race and Culture; The Free Press: Glencoe, IL, USA, 1950; p. 150. [Google Scholar]

- Glazer, N.; Moynihan, D.P. Beyond the Melting Pot: The Negroes, Puerto Ricans, Jews, Italians, and Irish of New York City; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Portes, A.; Zhou, M. Gaining the upper hand: Economic mobility among immigrant and domestic minorities. Ethn. Racial. Stud. 1992, 15, 491–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portes, A.; Zhou, M. The New Second Generation: Segmented Assimilation and Its Variants. Ann. Am. Acad. Pol. Soc. Sci. 1993, 530, 74–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldlust, J.; Richmond, A.H. A multivariate model of immigrant adaptation. Int. Migr. Rev. 1974, 8, 193–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmiento, A.V.; Pérez, M.V.; Bustos, C.; Hidalgo, J.P.; del Solar, J.I.V. Inclusion profile of theoretical frameworks on the study of sociocultural adaptation of international university students. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2019, 70, 19–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H. How to retain global talent? Economic and social integration of Chinese students in Finland. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marger, M.N. Social and human capital in immigrant adaptation: The case of Canadian business immigrants. J. Socio. Econ. 2001, 30, 169–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, B.C. Coping, acculturation, and psychological adaptation among migrants: A theoretical and empirical review and synthesis of the literature. Health Psychol. Behav. Med. 2014, 2, 16–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLaren, L.M. Anti-immigrant prejudice in Europe: Contact, threat perception, and preferences for the exclusion of migrants. Soc. Forces 2003, 81, 909–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinmann, J.P. The paradox of integration: Why do higher educated new immigrants perceive more discrimination in Germany? J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2019, 45, 1377–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, E.; Chiang, L.H.N.; Denton, N.A. Immigrant Adaptation in Multi-Ethnic Societies: Canada, Taiwan, and the United States; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 285–287. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd, M. At a Disadvantage: The Occupational Attainments of Foreign Born Women in Canada. Int. Migr. Rev. 1984, 18, 1091–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Economic Forum. Global Gender Gap Report 2021. Available online: https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_GGGR_2021.pdf (accessed on 31 October 2022).

- Samadi, M.; Sohrabi, N. The mediating role of the social problem solving for family process, family content, and adjustment. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 217, 1185–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chimbos, P.D. A comparison of the social adaptation of Dutch, Greek and Slovak immigrants in a Canadian community. Int. Migr. Rev. 1972, 6, 230–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giddens, A. The Constitution of Society: Outline of the Theory of Structuration; China Renmin University Press: Beijing, China, 2016; pp. 63–84. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. Practical Reason: On the Theory of Action; Joint Publishing: Hong Kong, China, 2007; p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.H. Index of assimilation for rural to urban migrants: A further analysis of the conceptual framework of assimilation theory. J. Popul. Econ. 2010, 2, 64–70. [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre. The Production of Space; Blackwell: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1991; p. 14. [Google Scholar]

- Kõu, A.; Bailey, A. “Movement is a constant feature in my life”: Contextualising migration processes of highly skilled Indians. Geoforum 2014, 52, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigad, L.I.; Eisikovits, R.A. Migration, motherhood, marriage: Cross-cultural adaptation of North American immigrant mothers in Israel. Int. Migr. 2009, 47, 63–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Man, G.; Chou, E. Transnational familial strategies, social reproduction, and migration: Chinese immigrant women professionals in Canada. J. Fam. Stud. 2020, 26, 345–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emerson, R.M.; Fretz, R.I.; Shaw, L.L. Writing Ethnographic Fieldnotes; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1995; p. 114. [Google Scholar]

- Uriely, N. Rhetorical ethnicity of permanent sojourners: The case of Israeli immigrants in the Chicago area. Int. Sociol. 1994, 9, 431–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siu, P.C. The sojourner. Am. J. Sociol. 1952, 58, 34–44. [Google Scholar]

- Bonacich, E.A. Theory of Middleman Minorities. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1973, 38, 583–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Tian, H.; Chang, J. Chinese first, woman second: Social media and the cultural identity of female immigrants. Asian J. Women’s Stud. 2021, 27, 22–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khvorostianov, N.; Elias, N.; Nimrod, G. “Without it I am nothing”: The Internet in the lives of older immigrants. New Media Soc. 2011, 14, 583–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miconi, A. News from the Levant: A Qualitative Research on the Role of Social Media in Syrian Diaspora. Soc. Media Soc. 2020, 6, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; de Haan, M.; Koops, W. Learning to be a mother: Comparing two groups of Chinese immigrants in the Netherlands. Asian Pac. Migr. J. 2019, 28, 220–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, T.W. Investment in human capital. Am. Econ. Rev. 1961, 51, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- National Tax Agency. Current Survey of Private Sector Salaries 2021. Available online: https://www.nta.go.jp/publication/statistics/kokuzeicho/minkan2020/pdf/000.pdf (accessed on 31 October 2022).

- Cooley, C.H. On Self and Social Organization; Huaxia Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2015; pp. 335–340. [Google Scholar]

- Nakane, C. Personal Relations in a Vertical Society—A Theory Of Homogeneous Society; Kodansha: Tokyo, Japan, 1967; pp. 123–131. [Google Scholar]

- Habermas, J. Nachmetaphysisches Denken; YINLIN PRESS: Nanjing, China, 2001; p. 59. [Google Scholar]

- Lebra, T.S. Japanese Patterns of Behavior; University Press of Hawaii: Honolulu, HI, USA, 1976; p. 38. [Google Scholar]

- Vogt, G. Multiculturalism and trust in Japan: Educational policies and schooling practices. Jpn. Forum. 2017, 29, 77–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massey, D.S.; Goldring, L.; Durand, J. Continuities in transnational migration: An analysis of nineteen Mexican communities. Am. J. Sociol. 1994, 99, 1492–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andriescu, M. How Policies Select Immigrants: The Role of the Recognition of Foreign Qualifications. Migr. Lett. 2018, 15, 461–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu-Farrer, G.; Yeoh, B.S.; Baas, M. Social construction of skill: An analytical approach toward the question of skill in cross-border labour mobilities. J. Ethn. Migr. 2021, 47, 2237–2251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Japan Revitalization Strategy 2016. Available online: https://www.kantei.go.jp/jp/singi/keizaisaisei/pdf/zentaihombun_160602_en.pdf (accessed on 31 October 2022).

- Immigration Services Agency of Japan. Points-Based Preferential Immigration Treatment for Highly-Skilled Foreign Professionals. Available online: https://www.isa.go.jp/common/uploads/pub-291_01.pdf (accessed on 31 October 2022).

- Immigration Services Agency of Japan. Number of Highly-Skilled Foreign Professionals by Nationality and Region in 2022. Available online: https://www.moj.go.jp/isa/content/930003527.pdf (accessed on 31 October 2022).

- Kim, K.C.; Hurh, W.M. Adhesive sociocultural adaptation of Korean immigrants in the US: An alternative strategy of minority adaptation. Int. Migr. Rev. 1984, 18, 188–216. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, B. Becoming a Rooted Cosmopolitan? The Case Study of 1.5 Generation New Chinese Migrants in New Zealand. J. Chin. Overseas 2018, 14, 244–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hays Specialist. The 2018 Hays Asia Salary Guide. Available online: https://www.hays.com.my/documents/276768/0/Hays+Asia+Salary+Guide+2018+EN.pdf/c6b0c692-c4eb-8647-9a2b-277c1ec1d175?t=1596561697142 (accessed on 31 October 2022).

- Hof, H.B. Mobility as a Way of Life: European Millennials’ Labour Migration to Asian Global Cities. Ph.D. Thesis, Waseda University, Tokyo, Japan, 2018. [Google Scholar]

| Characteristic | Number of Participants | |

|---|---|---|

| Age range | 25–29 | 7 |

| 30–34 | 18 | |

| 35–39 | 7 | |

| 40–44 | 6 | |

| Length of stay in Japan | 5 yrs to 10 yrs | 8 |

| 11 yrs to 20 yrs | 25 | |

| 21 yrs and more | 5 | |

| Marital status | Single | 3 |

| Relationship | 5 | |

| Married | 28 | |

| Divorced | 2 | |

| Has a child or children | 29 | |

| Citizenship | Chinese | 34 |

| Japanese | 4 | |

| Education level | Bachelor | 9 |

| Master | 27 | |

| PhD | 2 | |

| Occupation | Sales | 9 |

| Programmer | 8 | |

| Marketer | 8 | |

| Consultant | 6 | |

| Finance | 3 | |

| Others | 4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, J.; Chen, S. Embedded Coexistence: Social Adaptation of Chinese Female White-Collar Workers in Japan. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1294. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15021294

Liu J, Chen S. Embedded Coexistence: Social Adaptation of Chinese Female White-Collar Workers in Japan. Sustainability. 2023; 15(2):1294. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15021294

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Jing, and Shaojun Chen. 2023. "Embedded Coexistence: Social Adaptation of Chinese Female White-Collar Workers in Japan" Sustainability 15, no. 2: 1294. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15021294

APA StyleLiu, J., & Chen, S. (2023). Embedded Coexistence: Social Adaptation of Chinese Female White-Collar Workers in Japan. Sustainability, 15(2), 1294. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15021294