Understanding the Complexity of Rural Tourism Business: Scholarly Perspective

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Marketability in Rural Tourism

2.2. Sustainability in Rural Tourism

2.3. Participatory in Rural Tourism

2.4. Crisis/Disaster Mitigation Management in Rural Tourism

3. Materials and Methods

- Stage (I): Data extraction

- Stage (II): Data refinement

- Stage (III): Data analysis

4. Results and Discussion

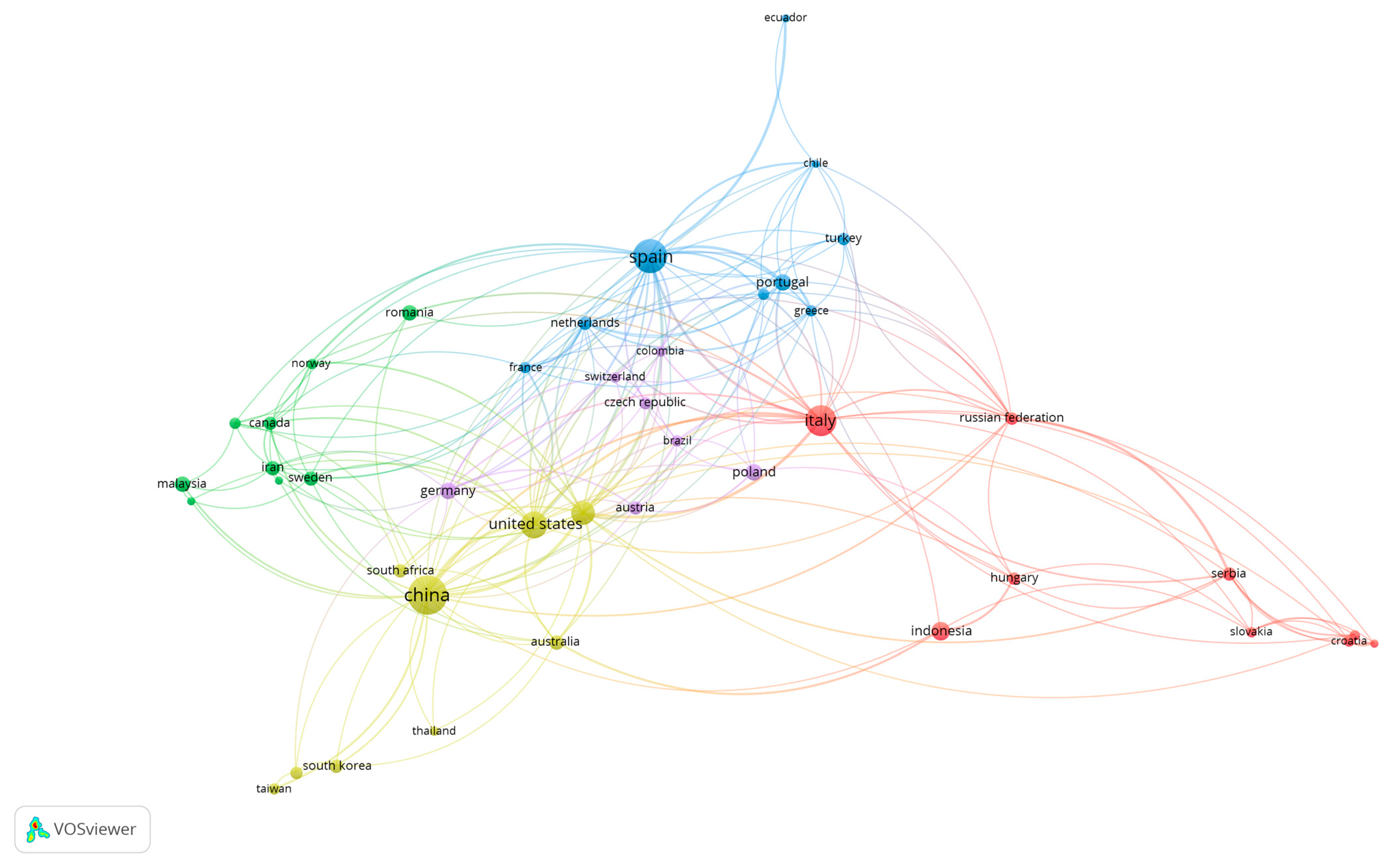

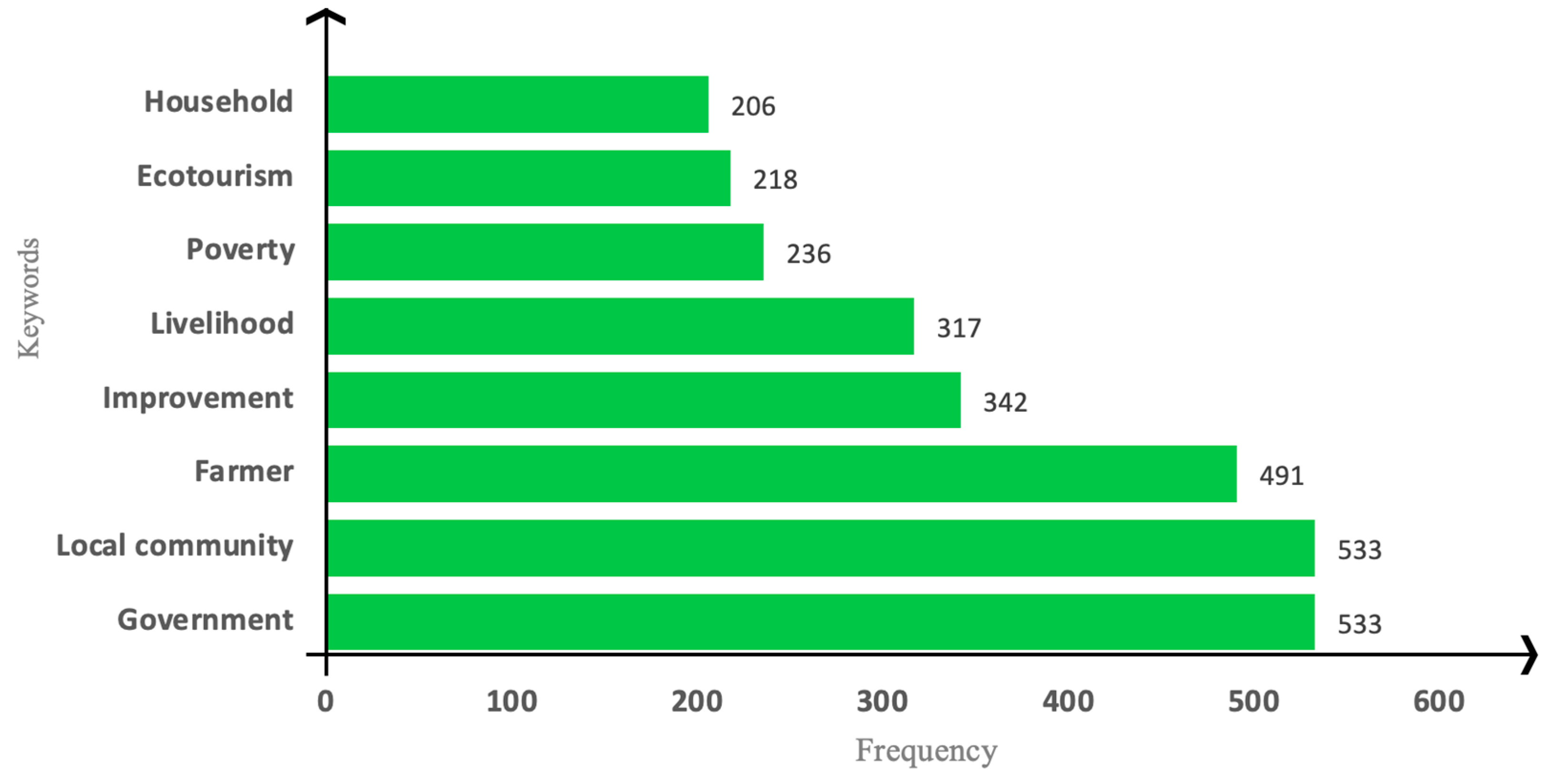

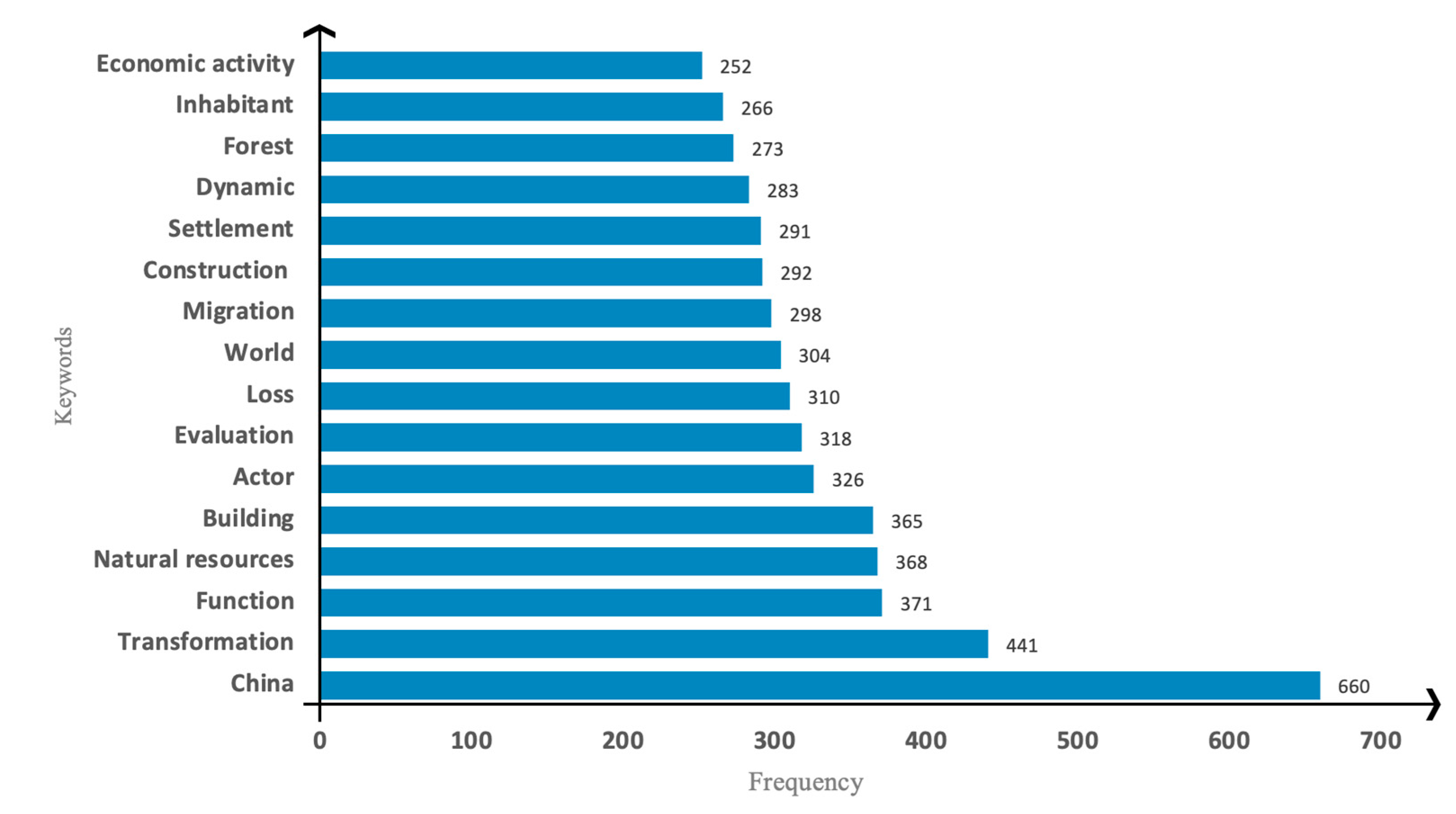

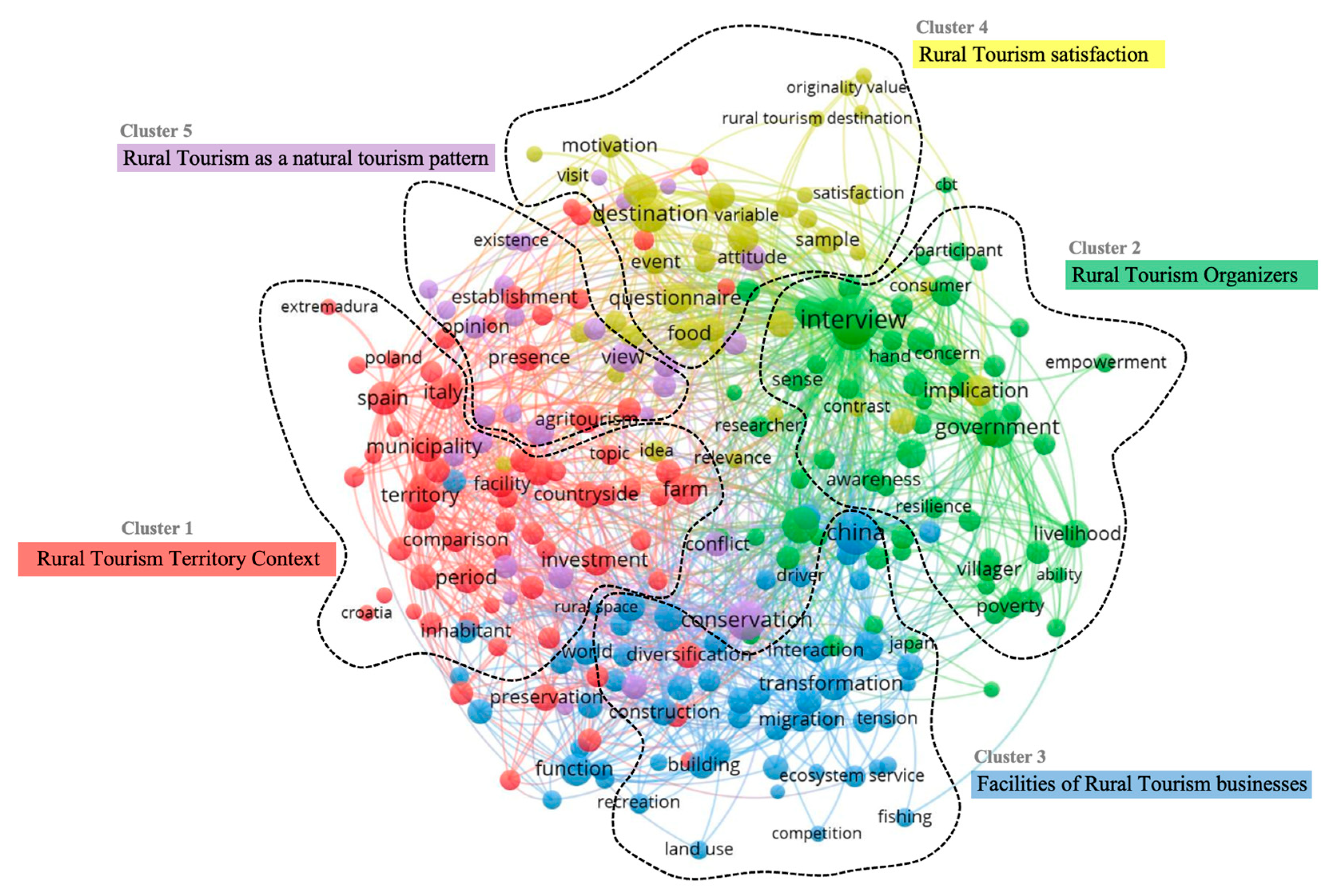

4.1. Overview of the Rural Tourism Businesses Literature

4.2. Rural Tourism Businesses Literature Response to Driving Forces (Marketability, Participatory, Crisis Mitigation and Sustainability)

4.2.1. Rural Tourism Businesses Literature and Marketability

4.2.2. Rural Tourism Businesses Literature and Participatory

4.2.3. Rural Tourism Businesses Literature and Crisis/Disaster Mitigation

4.2.4. Rural Tourism Businesses Literature and Sustainability

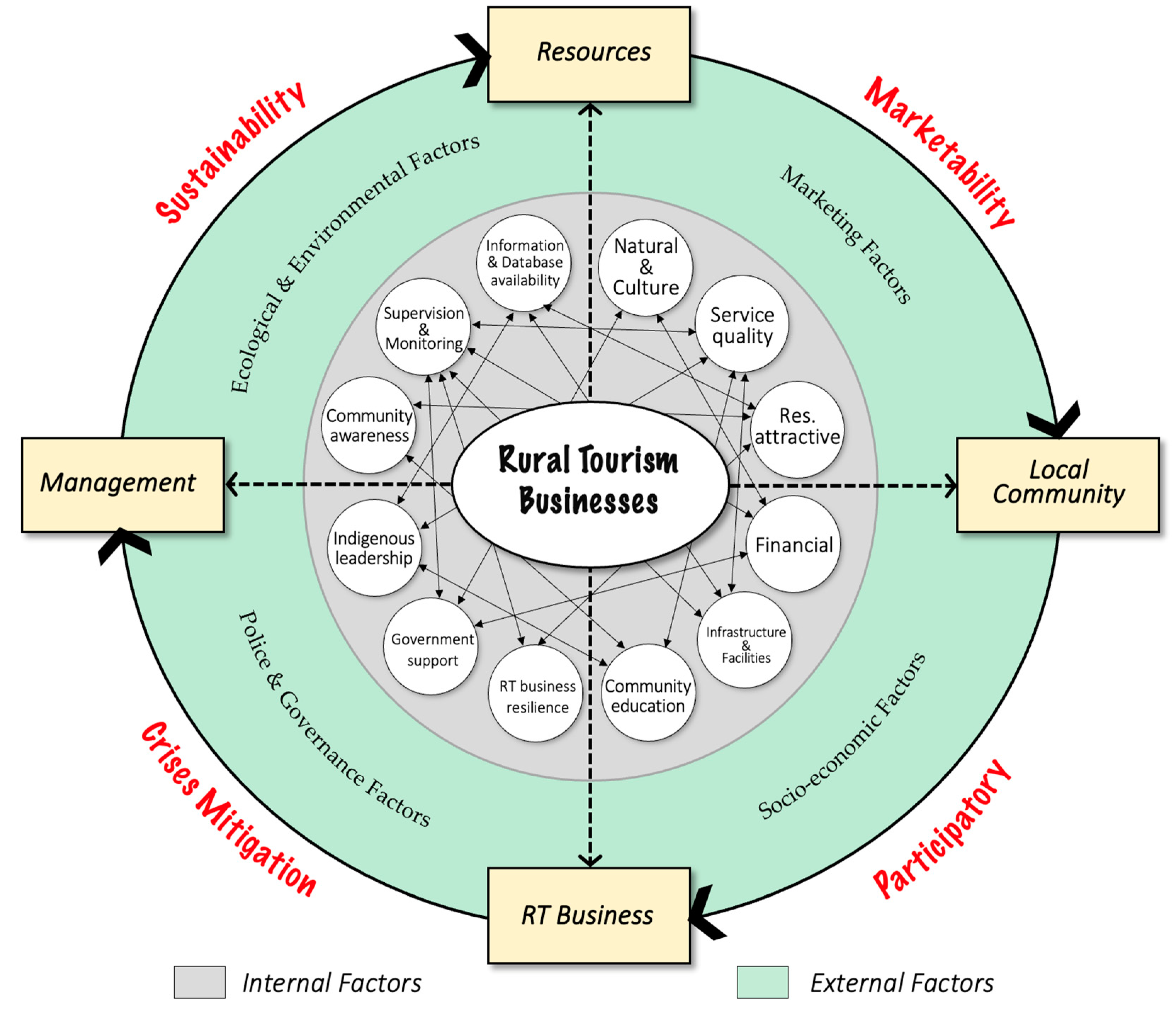

5. Complexity of Rural Tourism Business: Marketability, Participatory, Crisis/Disaster Mitigation and Sustainability

6. Conclusions, Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Situmorang, R.; Trilaksono, T.; Japutra, A. Friend or Foe? The complex relationship between indigenous people and policymakers regarding rural tourism in Indonesia. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2019, 39, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manaf, A.; Purbasari, N.; Damayanti, M.; Aprilia, N.; Astuti, W. Community-Based Rural Tourism in Inter-Organizational Collaboration: How Does It Work Sustainably? Lessons Learned from Nglanggeran Tourism Village, Gunungkidul Regency, Yogyakarta, Indonesia. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panzer-Krause, S. Rural Tourism in and after the COVID-19 Era: “Revenge Travel” or Chance for a Degrowth-Oriented Restart? Cases from Ireland and Germany. Tour. Hosp. 2022, 3, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polukhina, A.; Sheresheva, M.; Efremova, M.; Suranova, O.; Agalakova, O.; Antonov-Ovseenko, A. The Concept of Sustainable Rural Tourism Development in the Face of COVID-19 Crisis: Evidence from Russia. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2021, 14, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanfranchi, M.; Giannetto, C.; De Pascale, A. The Role of Nature-Based Tourism in Generating Multiplying Effects for Socio Economic Developmentt of Rural Areas. Qual.-Access Success 2014, 15, 96–100. [Google Scholar]

- Gallardo, J.H.; Stein, T.V. Participation, Power and Racial Representation: Negotiating Nature-Based and Heritage Tourism Development in the Rural South. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2007, 20, 597–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, L. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on rural tourism: A case study from Portugal. Anatolia 2021, 33, 157–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pongponrat, K.; Chantradoan, N.J. Mechanism of social capital in community tourism participatory planning in samui island, thailand. Tour. Int. Multidiscip. J. Tour. 2012, 7, 339–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Guzmán, T.; Sánchez-Cañizares, S.; Pavón, V. Community—Based tourism in developing countries: A case study. Tour. Int. Multidiscip. J. Tour. 2011, 6, 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, B.; Kastenholz, E. Rural tourism: The evolution of practice and research approaches—Towards a new generation concept? J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 1133–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Wu, B. Revitalizing traditional villages through rural tourism: A case study of Yuanjia Village, Shaanxi Province, China. Tour. Manag. 2017, 63, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosalina, P.D.; Dupre, K.; Wang, Y. Rural tourism: A systematic literature review on definitions and challenges. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 47, 134–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNWTO Rural Tourism. Available online: https://www.unwto.org/rural-tourism (accessed on 5 May 2022).

- Pongponrat, K. Participatory Management Process in Local Tourism Development: A Case Study on Fisherman Village on Samui Island, Thailand. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2011, 16, 57–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khairabadi, O.; Sajadzadeh, H.; Mohammadianmansoor, S. Assessment and evaluation of tourism activities with emphasis on agritourism: The case of simin region in Hamedan City. Land Use Policy 2020, 99, 105045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, D.; Xu, H.; Chung, Y. Perceived impacts of the poverty alleviation tourism policy on the poor in China. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2019, 41, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priatmoko, S.; Purwoko, Y. Anwani Does the Context of MSPDM Analysis Relevant in Rural Tourism? Case Study of Pentingsari, Nglanggeran, and Penglipuran. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Creative Economics, Tourism and Information Management—ICCETIM, Yogyakarta, Indonesia, 17–18 July 2019; pp. 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, W. The transference of Asian hospitality through food: Chef's inspirations taken from Asian cuisines to capture the essence of Asian culture and hospitality. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2017, 8, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrivastava, U.; Dwivedi, A.K. Manifestations of rural entrepreneurship: The journey so far and future pathways. Manag. Rev. Q. 2020, 71, 753–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghavvemi, S.; Woosnam, K.M.; Paramanathan, T.; Musa, G.; Hamzah, A. The effect of residents’ personality, emotional solidarity, and community commitment on support for tourism development. Tour. Manag. 2017, 63, 242–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Huang, X.; Zhang, Q. Tourism development and local borders in ancient villages in China. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2018, 9, 330–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Liu, J.; Innes, J.L. Conservation equity for local communities in the process of tourism development in protected areas: A study of Jiuzhaigou Biosphere Reserve, China. World Dev. 2019, 124, 104637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, T.T.T. Tourism in marine protected areas: Can it be considered as an alternative livelihood for local communities? Mar. Policy 2020, 115, 103891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M. Development and Assessment of Tourism in Valley of Flower National Park (Uttarakhand) India. Int. J. Acad. Res. Dev. 2018, 3, 452–455. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K.; Uysal, M.; Sirgy, M.J. How does tourism in a community impact the quality of life of community residents? Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 527–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, M.-Y.; Chen, C.-C.; Lin, H.-H.; Tseng, C.-H.; Hsu, C.-H. Research on the Impact of Popular Tourism Program Involvement on Rural Tourism Image, Familiarity, Motivation and Willingness. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakurar, M.; Olah, J. Definition of Rural Tourism and Its Characteristics in the Northern Great Plain Region. System 2008, VII, 777–782. [Google Scholar]

- Kotler, P.; Armstrong, G. Principles of Marketing; Prentice Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008; ISBN 9780132390026. [Google Scholar]

- Kastenholz, E.; Eusébio, C.; Carneiro, M.J. Segmenting the rural tourist market by sustainable travel behaviour: Insights from village visitors in Portugal. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2018, 10, 132–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohsen, M.G.; Dacko, S. An extension of the benefit segmentation base for the consumption of organic foods: A time perspective. J. Mark. Manag. 2013, 29, 1701–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khartishvili, L.; Muhar, A.; Dax, T.; Khelashvili, I. Rural Tourism in Georgia in Transition: Challenges for Regional Sustainability. Sustainability 2019, 11, 410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.-J.; Chen, L.-H.; Su, P.-A.; Morrison, A.M. The right brew? An analysis of the tourism experiences in rural Taiwan’s coffee estates. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2019, 30, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Q.; Hu, H.; Kavan, P. Factors Influencing Perceived Crowding of Tourists and Sustainable Tourism Destination Management. Sustainability 2016, 8, 976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNEP. Towards a Green Economy: Pathways to Sustainable Development and Poverty Eradication; UNEP: Nairobi, Kenya, 2011; ISBN 9789280731439. [Google Scholar]

- Lakner, Z.; Kiss, A.; Merlet, I.; Oláh, J.; Máté, D.; Grabara, J.; Popp, J. Building Coalitions for a Diversified and Sustainable Tourism: Two Case Studies from Hungary. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, M.M.; Wall, G.; Jin, M. Island livelihoods: Tourism and fishing at Long Islands, Shandong Province, China. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2016, 122, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapata, M.J.; Hall, C.M.; Lindo, P.; Vanderschaeghe, M. Can community-based tourism contribute to development and poverty alleviation? Lessons from Nicaragua. Curr. Issues Tour. 2011, 14, 725–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNWTO. UNWTO Annual Report a Year of Recovery 2010; UNWTO: Madrid, Spain, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Corral, S.; Hernández, J.; Ibáñez, M.N.; Ceballos, J.L.R. Transforming Mature Tourism Resorts into Sustainable Tourism Destinations through Participatory Integrated Approaches: The Case of Puerto de la Cruz. Sustainability 2016, 8, 680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jami, A.A.; Walsh, P.R. Wind Power Deployment: The Role of Public Participation in the Decision-Making Process in Ontario, Canada. Sustainability 2016, 8, 713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Qiu, Z.; Usio, N.; Nakamura, K. Tourism’s Impacts on Rural Livelihood in the Sustainability of an Aging Community in Japan. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suvdantsetseg, B.; Fukui, H.; Oe, M. Evaluation of Ecotourism Resources through Participatory Geo-Spatial Approach: A Case of the Biger City, Mongolia. ASEAN J. Hosp. Tour. 2011, 10, 162–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaranta, G.; Citro, E.; Salvia, R. Economic and Social Sustainable Synergies to Promote Innovations in Rural Tourism and Local Development. Sustainability 2016, 8, 668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa, E.B.; Rotarou, E.S. Sustainable Development or Eco-Collapse: Lessons for Tourism and Development from Easter Island. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Jaafar, M.; Ramayah, T. Urban vs. rural destinations: Residents’ perceptions, community participation and support for tourism development. Tour. Manag. 2017, 60, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamarudin, K.H.; Wahid, S.N.A.; Chong, N.O. Staying Afloat: Operating Tourism in Disaster-Prone Areas of Mesilou, Sabah. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2020, 409, 012004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNISDR. 2009 UNISDR Terminology on Disaster Risk Reduction; UNISDR: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Honert, R.C.V.D. Improving Decision Making about Natural Disaster Mitigation Funding in Australia—A Framework. Resources 2016, 5, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, A.; Yeskey, K.; Garantziotis, S.; Arnesen, S.; Bennett, A.; O’Fallon, L.; Thompson, C.; Reinlib, L.; Masten, S.; Remington, J.; et al. Integrating Health Research into Disaster Response: The New NIH Disaster Research Response Program. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orishev, A.B.; Mamedov, A.A.; Zalysin, I.Y.; Kotusov, D.V.; Grigoriev, S.L. The Development of Travel and Tourism Industry in Iran. Int. J. Criminol. Sociol. 2020, 9, 2173–2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, K.; Hotes, S.; Ichinose, T.; Doko, T.; Wolters, V. Hotspots of Agricultural Ecosystem Services and Farmland Biodiversity Overlap with Areas at Risk of Land Abandonment in Japan. Land 2021, 10, 1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sriram, D.; Dorasamy, N.; Vipul, N. Disaster Management in India: Need for an Integrated Approach. Disaster Adv. 2022, 15, 60–68. [Google Scholar]

- Zakhiyah, I.; Suprapto, N.; Setyarsih, W. Prezi Mind Mapping Media in Physics Learning: A Bibliometric Analysis. In Proceedings of the Journal of Physics: Conference Series, Nanchang, China, 26–28 October 2021; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2021; Volume 2110, p. 012015. [Google Scholar]

- Scopus. Abstract & Citation Database. 2021. Available online: https://www.elsevier.com/solutions/scopus (accessed on 30 October 2022).

- Kabil, M.; Priatmoko, S.; Magda, R.; Dávid, L. Blue Economy and Coastal Tourism: A Comprehensive Visualization Bibliometric Analysis. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera-Franco, G.; Montalván-Burbano, N.; Mora-Frank, C.; Moreno-Alcívar, L. Research in Petroleum and Environment: A Bibliometric Analysis in South America. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. Plan. 2021, 16, 1109–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnham, J.F. Scopus database: A review. Biomed. Digit. Libr. 2006, 3, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera-Franco, G.; Montalván-Burbano, N.; Mora-Frank, C.; Bravo-Montero, L. Scientific Research in Ecuador: A Bibliometric Analysis. Publications 2021, 9, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Khoury, A.; Hussein, S.A.; Abdulwhab, M.; Aljuboori, Z.M.; Haddad, H.; Ali, M.A.; Abed, I.A.; Flayyih, H.H. Intellectual Capital History and Trends: A Bibliometric Analysis Using Scopus Database. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- elsevier.com Discover Why the World’s Leading Researchers and Organizations Choose Scopus. Available online: https://www.elsevier.com/solutions/scopus/why-choose-scopus (accessed on 12 January 2022).

- Hallinger, P.; Nguyen, V.-T. Mapping the Landscape and Structure of Research on Education for Sustainable Development: A Bibliometric Review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabindra, K. Maharana Bibliometric Analysis of Orissa University of Agricultural Technology’s Research Output as Indexed in Scopus in 2008–2012. Chin. Librariansh. Int. Electron. J. 2013, 36, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Netto, C.d.O.; Tello-Gamarra, J.E. Sharing Economy: A Bibliometric Analysis, Research Trends and Research Agenda. J. Technol. Manag. Innov. 2020, 15, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. Manual de VOSviewer; University Leiden: Leiden, The Nethrelands, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, F.; Jia, X.; Zhao, Z.; Chen, C.-C.; Xu, F.; Geng, Z.; Song, X. Bibliometric analysis on tendency and topics of artificial intelligence over last decade. Microsyst. Technol. 2019, 27, 1545–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyk, E.; Szalai, A.; Palkovics, A.; Farkas, J.Z. Policy Gaps Related to Sustainability in Hungarian Agribusiness Development. Agronomy 2022, 12, 2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aytuğ, H.K.; Mikaeili, M. Evaluation of Hopa’s Rural Tourism Potential in the Context of European Union Tourism Policy. Procedia Environ. Sci. 2017, 37, 234–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hocevar, M.; Bartol, T. Mapping urban tourism issues: Analysis of research perspectives through the lens of network visualization. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2021, 7, 818–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Real, J.L.; Uribe-Toril, J.; Valenciano, J.D.P.; Gázquez-Abad, J.C. Rural tourism and development: Evolution in Scientific Literature and Trends. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2020, 46, 1322–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edit, H.; András, P. Climate Adaptation and Landscape Architecture in Urban Environment. In Proceedings of the 10th International Scientific and Expert Conference TEAM 2022, Slavonski Brod, Croatia, 21–22 September 2022; Damjanovic, D., Stojsic, J., Mirosavljevic, K., Sivric, H., Eds.; University of Slavonski Brod: Slavonski Brod, Croatia, 2022; pp. 469–4575. [Google Scholar]

- Mugauina, R.; Rey, I.Y.; Sabirova, R.; Rakhisheva, A.B.; Berstembayeva, R.; Beketova, K.N.; Zhansagimova, A. Development of Rural Tourism after the Coronavirus Pandemic. J. Environ. Manag. Tour. 2021, 11, 2020–2027. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, S.C. Which Heritage? Nature, Culture, and Identity in French Rural Tourism. Fr. Hist. Stud. 2002, 25, 475–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Place, S.E. Nature tourism and rural development in Tortuguero. Ann. Tour. Res. 1991, 18, 186–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plokhikh, R.; Fodor, G.; Shaken, A.; Berghauer, S.; Aktymbayeva, A.; Tóth, A.; Mika, M.; Dávid, L.D. Investigation of environmental determinants for agritourism development in almaty region of kazakhstan. Geoj. Tour. Geosites 2022, 41, 354–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, H. Sustainable Tourism Is Not the Same as Responsible Tourism. In Responsible Tourism, 2nd ed.; Goodfellow Publishers: Oxford, UK, 2016; pp. 15–29. ISBN 978-1-910158-84-5. [Google Scholar]

- Augustyn, M. National Strategies for Rural Tourism Development and Sustainability: The Polish Experience. J. Sustain. Tour. 1998, 6, 191–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richins, H.; Hull, J. Mountain Tourism: Experiences, Communities, Environments and Sustainable Futures; CABI Publishing: Wallingford, UK, 2016; ISBN 978-1-78064-460-8. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, P.A. Realizing Rural Community-Based Tourism Development: Prospects for Social Economy Enterprises. J. Rural. Community Dev. 2010, 5, 150–162. Available online: https://journals.brandonu.ca/jrcd/issue/view/10 (accessed on 30 October 2022).

- Paresishvili, O.; Kvaratskhelia, L.; Mirzaeva, V. Rural tourism as a promising trend of small business in Georgia: Topicality, capabilities, peculiarities. Ann. Agrar. Sci. 2017, 15, 344–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maliuta, L.; Harmatiy, N.; Fedyshyn, I.; Tkach, U. Rural development in the european union through tourism potential. Manag. Theory Stud. Rural. Bus. Infrastruct. Dev. 2022, 43, 555–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, X.; Yao, Y.; Li, J. Sociocultural Impacts of Tourism on Residents of World Cultural Heritage Sites in China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, N.J.; Dearden, P. Why local people do not support conservation: Community perceptions of marine protected area livelihood impacts, governance and management in Thailand. Mar. Policy 2014, 44, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mottiar, Z.; Boluk, K.; Kline, C. The roles of social entrepreneurs in rural destination development. Ann. Tour. Res. 2017, 68, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Yang, R.; Chen, M.H.; Su, C.H.J.; Zhi, Y.; Xi, J. Effects of rural revitalization on rural tourism. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 47, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prestia, G.; Scavone, V. Enhancing the Endogenous Potential of Agricultural Landscapes: Strategies and Projects for a Inland Rural Region of Sicily. In Smart and Sustainable Planning for Cities and Regions; Bisello, A., Vettorato, D., Laconte, P., Costa, S., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 635–648. [Google Scholar]

- Bacsi, Z.; Dávid, L.D.; Hollósy, Z. Industry Differences in Productivity—In Agriculture and Tourism by Lake Balaton, Hungary. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatimah, T. The Impacts of Rural Tourism Initiatives on Cultural Landscape Sustainability in Borobudur Area. Procedia Environ. Sci. 2015, 28, 567–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boronyak, L.; Asker, S.; Carrard, N.; Paddon, M. Effective Community Based Tourism: A Best Practice Manual for Peru; APEC Tourism Working Group; Institute for Sustainable Futures, University of Technology Sydney: Sydney, Australia, 2010; p. 174. [Google Scholar]

- Peña, A.P.; Jamilena, D.M.F. Market orientation adoption in rural tourism: Impact on business outcomes and the perceived value. Int. Rev. Public Nonprofit Mark. 2011, 8, 195–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajake, A.O. Tourism marketing strategies performance: Evidence from the development of peripheral areas in Cross River State, Nigeria. Geojournal 2015, 81, 641–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mshenga, P.M.; Richardson, R.B. Micro and small enterprise participation in tourism in coastal Kenya. Small Bus. Econ. 2012, 41, 667–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Commission on Environment & Development Our Common Future, 7th ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1987; ISBN 019282080X.

- Ana, M.-I. Ecotourism, Agro-Tourism and Rural Tourism in the European Union. Cactus Tour. J. 2017, 15, 6–14. [Google Scholar]

- Rajović, G.; Bulatović, J. Tourism Rural Development in the European Context: Overview. Sci. Electron. Arch. 2017, 10, 58–66. [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht, J.N.; Haid, M.; Finkler, W.; Heimerl, P. What’s in a name? The meaning of sustainability to destination managers. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 30, 32–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.S.; Bai, B.H.; Kim, P.B.; Chon, K. Review of reviews: A systematic analysis of review papers in the hospitality and tourism literature. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 70, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priatmoko, S.; Kabil, M.; Purwoko, Y.; Dávid, L. Rethinking Sustainable Community-Based Tourism: A Villager’s Point of View and Case Study in Pampang Village, Indonesia. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, H.; Santilli, R. Community-Based Tourism: A Success? CABI: Leeds, UK, 2009; p. 39. [Google Scholar]

| Elements | Search Query * |

|---|---|

| Marketability | ((TITLE-ABS-KEY (“rural tourism” OR “rural tourism business*” OR “rural tourism enterprise*”)) AND (TITLE-ABS-KEY (village OR mountain OR lake OR river OR coastal OR indigenous OR forest* OR remote OR traditional OR agriculture* OR heritage))) AND (TITLE-ABS-KEY (market*)) |

| Participatory | ((TITLE-ABS-KEY (“rural tourism” OR “rural tourism business*” OR “rural tourism enterprise*”)) AND (TITLE-ABS-KEY (village OR mountain OR lake OR river OR coastal OR indigenous OR forest* OR remote OR traditional OR agriculture* OR heritage))) AND (TITLE-ABS-KEY (participat*)) |

| Crisis Mitigation | ((TITLE-ABS-KEY (“rural tourism” OR “rural tourism business*” OR “rural tourism enterprise*”)) AND (TITLE-ABS-KEY (village OR mountain OR lake OR river OR coastal OR indigenous OR forest* OR remote OR traditional OR agriculture* OR heritage))) AND (TITLE-ABS-KEY (disaster OR cris* OR risk OR mitigat*)) |

| Sustainability | ((TITLE-ABS-KEY (“rural tourism” OR “rural tourism business*” OR “rural tourism enterprise*”)) AND (TITLE-ABS-KEY (village OR mountain OR lake OR river OR coastal OR indigenous OR forest* OR remote OR traditional OR agriculture* OR heritage))) AND (TITLE-ABS-KEY (sustaina*)) |

| Topic(s) | Issues | Contributor(s) |

|---|---|---|

| RT | Sociocultural, environment impacts of tourism and the role of entrepreneur community connection in rural tourism development | [81,82,83] |

| RT & Marketability | Sustainable behavior to build experience visitors, visitor segmentation, and destination branding. Integration of general provisions with local stakeholders and create travel program involvement for boosting popularity and imagery of the destination | [26,29,31,32] |

| RT & Sustainability | Cooperative for equitable distribution, appropriate benefit sharing. The participation of local governments, businesses and residents in tourism concern to livelihood, natural resource, and socio cultural. Boosting awareness of planning and enhancing the knowledge base used to make decisions about sustainable tourism management | [11,35,36,84] |

| RT & Participatory | Community participation on residents’ support for tourism development. Collaboration and involvement of the related inter-organizational stakeholders by the local community. Developing social networks with the local government and corporate sector to increase levels of trust and social capital. | [2,41,43,45] |

| RT & Crisis/Disaster Mitigation | The local government has not taken social risks into account, and reflected in local policy. Products and services mitigation are very relevant objectives. Common problem affected by the COVID-19 pandemic and to ensure the safety of tourists, ensure that health problems will be contained. Managing of spatial overlap between farm and off-farm activities. Community resilience in combining of internal and external factors. Disasters and climate change both should be addressed locally, and local knowledge and understanding must be used to help local decision-making. | [36,46,50,51,52] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Priatmoko, S.; Kabil, M.; Akaak, A.; Lakner, Z.; Gyuricza, C.; Dávid, L.D. Understanding the Complexity of Rural Tourism Business: Scholarly Perspective. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1193. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15021193

Priatmoko S, Kabil M, Akaak A, Lakner Z, Gyuricza C, Dávid LD. Understanding the Complexity of Rural Tourism Business: Scholarly Perspective. Sustainability. 2023; 15(2):1193. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15021193

Chicago/Turabian StylePriatmoko, Setiawan, Moaaz Kabil, Ali Akaak, Zoltán Lakner, Csaba Gyuricza, and Lóránt Dénes Dávid. 2023. "Understanding the Complexity of Rural Tourism Business: Scholarly Perspective" Sustainability 15, no. 2: 1193. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15021193

APA StylePriatmoko, S., Kabil, M., Akaak, A., Lakner, Z., Gyuricza, C., & Dávid, L. D. (2023). Understanding the Complexity of Rural Tourism Business: Scholarly Perspective. Sustainability, 15(2), 1193. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15021193