1. Introduction

The Nizhny Tagil Charter for The Industrial Heritage (2003) issued by The International Committee for the Conservation of the Industrial Heritage (TICCIH) clearly defines the industrial heritage as the sum of the tangible and intangible heritage generated during industrial development. It includes the remnants of social life, such as industrial production sites, plant support facilities, places for workers to eat and sleep, transportation systems of the time, etc. These industrial relics should be the name card of the city or the representative of industrial culture. However, in the post-industrial era, many companies with the industrial heritage do not know how to handle these high-quality resources. Some industrial heritage is placed in museums and is preserved in the form of heritage culture. However, in recent years, with the increase in industrial museums and the intensification of homogeneous competition, the resources of many industrial museums have been idle. How to effectively utilize these industrial heritage resources has become a practical challenge for companies [

1,

2], and an important research topic in the post-industrial era.

At present, the conservation and utilization of the industrial heritage are mainly conducted in the form of heritage park development [

3], heritage tourism [

4], and heritage culture development [

5], in the context of urban renewal [

6]. These studies attach importance to the renovation of relics and incorporate them into plans conducive to their new functions [

7]. They focus on architecture and tourism from a technical perspective. However, many management entities that protect and renovate the industrial heritage are business organizations. Therefore, how to effectively utilize industrial heritage resources at the corporate management level falls under management science. In this regard, it is necessary to explore the conservation and utilization of the industrial heritage from the perspective of management [

8]. Currently, it lacks studies on the reuse of industrial heritage resources from a business management perspective, weakening the guidance of existing theories on business practice. Although enterprises engaged in the industrial heritage implemented various management innovations, the academia lacks the summary of the process mechanism of the transformation of these enterprises.

This study explores how to evoke industrial heritage resources for the sustainable development of enterprises. An important reason industrial heritage resources are difficult to be activated is that they are always embedded in the original production and application scenarios and thus are not easily exploited. Thus, the change in application scenarios of the industrial heritage becomes the key to activating its value. Existing studies on the activation of the industrial heritage mainly focus on innovating and utilizing resources [

9]. It fails to take full account of changes in the “environment”. This study requires a theoretical perspective that considers the interaction between objects, people, and the environment. Affordance theory originates from ecological psychology and describes how people or animals perceive what actions are possible with a given object in different contexts. The core idea of this theory is that the same object or resource produces different affordances based on different cognitions. For example, when a piece of wood is in a kitchen, it generates the affordance of burning and releasing heat, while in a wood carving studio, it generates the affordance of beauty. Affordance theory is independent of subjective arguments and emphasizes objective relationship evolution. With the mature application of this theory in fields such as enterprise information managements [

10], it demonstrates its value in elaborating on complex relationships [

11]. This study not only explores the development and utilization of industrial heritage resources from a business management perspective, but also tries to use the affordance theory to explain the relationship between resources, people, and contexts involved in industrial heritage resources. According to the affordance theory, the key to evoking industrial heritage resources lies in how the management perceive the affordances of heritage resources and implement organizational behaviors to achieve the affordances. For example, how to discover the new affordances of heritage resources and exploit them in an Internet scenario.

We selected Taoxichuan Ceramic Cultural and Creative Industrial Park as the research object and conducted an in-depth study on developing and utilizing industrial heritage resources. Taoxichuan Ceramic Cultural and Creative Industrial Park is a successful example of protecting and utilizing China’s industrial heritage. Its management practice is to create a series of cultural and creative industry platforms full of vitality and vigor through innovative development and utilization of discarded ceramic production relics. Its recognition of the attributes of industrial heritage resources and the development and utilization process are dynamic and complex. Therefore, we adopted the method of case study. We focused on how to evoke the industrial heritage and achieve sustainable development of enterprises, with a view to addressing three questions: (1) what are the key drivers evoking industrial heritage resources to achieve sustainable development? (2) what is the process mechanism of evoking industrial heritage resources? (3) how to realize the sustainable development of enterprises with industrial heritage resources? Research findings have indicated that: (1) the creation of a culturally recognized context performs a vital role in evoking industrial heritage; (2) the evocation of industrial heritage resources is a dynamic process from the realization of fundamental values to the actualization of high-level values; and (3) the evoked industrial heritage resources can achieve sustainable corporate development.

In this regard, this paper is divided into the following parts. First, it provides readers with a theoretical background and a research context, and two concepts, namely the sustainable development of the industrial heritage and the affordance theory, are discussed. Second, it gives a brief introduction to the selected cases and research methods to help illustrate the arguments of this research. Finally, through the description and discussion of the case stories, it draws conclusions related to the evocation of industrial heritage resources for sustainable corporate development.

4. Case Study

4.1. Case Background

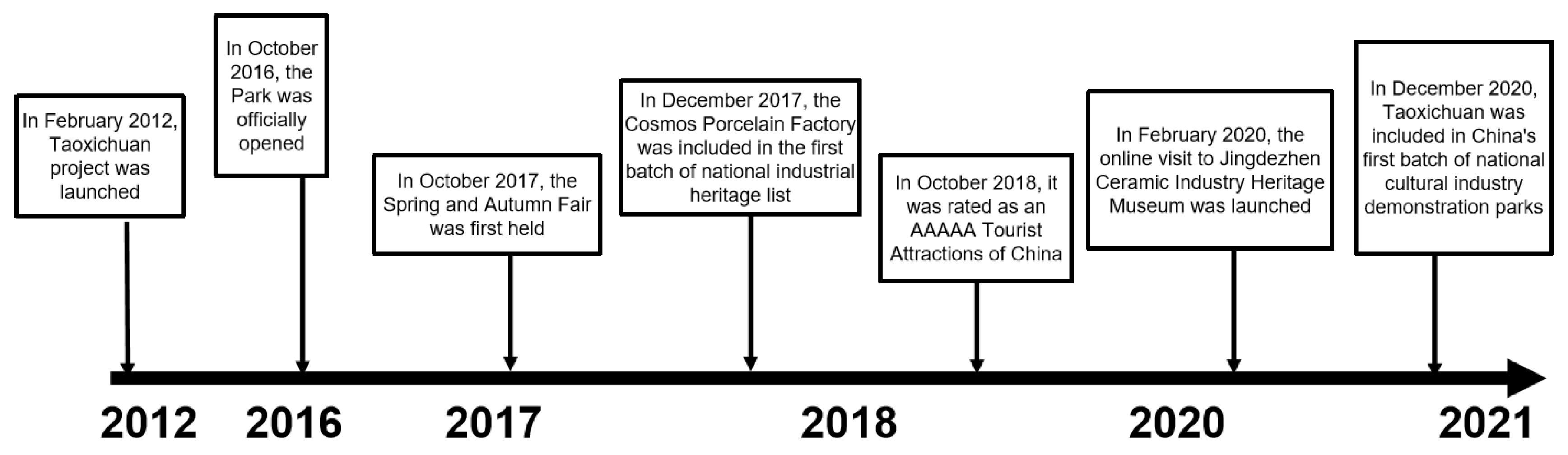

Located in Jingdezhen, the porcelain capital of China, Taoxichuan is a project for the conservation and utilization of modern ceramic industrial heritage. Its predecessor was the Cosmos Porcelain Factory, one of the ten state-owned porcelain factories in Jingdezhen, known as the “Jingdezhen Royal Porcelain Factory”. Established in the 1950s, the factory had won many awards for its excellent product quality and was once the factory that earned foreign exchange in the era of the planned economy. After the 1990s, many state-run porcelain factories were phased out by the times, and large porcelain industrial plants were left idle and abandoned. Taoxichuan became a rusty, unpopular, and lifeless abandoned plant area. The project was launched in 2012 to salvage and restore modern industrial facilities, such as coal-fired tunnel kilns, round kilns, and 22 old factory buildings of various eras. Currently, after several years of protective development and specialized operation, the old plant area of Cosmos Porcelain Factory has reached 73,000 m

2 for the cultural industry; over 170 big brands have been introduced, including nearly 150 cultural enterprises, accounting for more than 80% of the total number of enterprises. These cultural enterprises are mainly engaged in porcelain creativity, cultural communication, art exhibition, art design, intangible cultural heritage protection, education, and training, etc. By 2020, Taoxichuan Cultural and Creative Street boasted a total revenue of the main business of 1.323 billion yuan, 142 cultural enterprises, over 5000 employees, and a cumulative number of about 15,000 employees and entrepreneurs (see

Figure 2 for the key milestones of Taoxichuan).

4.2. Create a Situation to Evoke Industrial Heritage Resources in Taoxichuan

The awareness of affordance is the prerequisite for affordance activities [

36]. The management of Taoxichuan has realized that, in the context of industrial technological progress, Taoxichuan’s industrial heritage resources, such as factory buildings and machinery, have lost their original functions. There have been opposing perceptions about the disposal of the industrial heritage, and many managers deem that the old resources are hindering the development of enterprises, and even put forward the slogan of “demolishing the old and building the new”. For example, the Malt Building, the industrial heritage of Shuanghesheng Brewery in Beijing, was demolished overnight even though it had been included in the scope of heritage protection. These resources were not reused due to the failure of enterprise managers to discover that industrial heritage contains properties to be exploited. The management of Taoxichuan found that, although the ceramic production devices in Taoxichuan had lost their role in creating value, these resources reflect the characteristics of the production process of different periods and the cultural attributes of the past state of life. The affordance theory suggests that the emergence of object affordance requires the targeted creation of specific contexts based on the attributes of resources [

41]. To demonstrate the cultural attributes of the industrial heritage resources in Taoxichuan, the owners of the industrial resources should first change the backward situation of hand-made ceramics not adapted to industrial production under technological development and create a context that identifies with the culture of traditional ceramic manufacturing.

The identification of affordance is highly related to the purpose of the actors [

30]. The management of Taoxichuan abandoned the idea of knocking down and rebuilding the old factory. Instead, it created a context centered on the industrial heritage of Taoxichuan according to the characteristics of ceramic culture. On the one hand, the management of Taosxichuan hired a renowned company engaged in heritage design (Beijing Tsinghua Tongheng Urban Planning and Design Institute) to plan and design the abandoned plant area and put forward the conservation and development principle of maintaining the originality of industrial heritage and conducted scientific planning and design for it. On the other hand, the management actively promoted the concept of ceramic culture development, invited some creative agencies to set up independent ceramic art spaces for ceramic creation, and visited Jingdezhen Ceramic Institute to attract college graduates and young creators interested in ceramic development to settle in Taoxichuan. Additionally, to improve the chances of customers continuing with the products and services, Taoxichuan has planned to provide supporting services for tourists, business travelers, local residents, and other consumers to effectively enhance the identification of ceramic artists and consumers with the ceramic culture represented by Taoxichuan. With these measures, the company has successfully created a context for the identification with ceramic culture. Based on the context of cultural identity, the management identified the manufacturing function of industrial heritage resources, which is the basic affordance of heritage resources.

As mentioned by the enterprise manager, the century-old Taoxichuan is a site attracting many people with cultural empathy. If it cannot move retired and laid-off workers in Taoxichuan, how can it touch and attract visitors outside Taoxichuan. It’s the same reason why we are moved when we see ancient Roman architecture. We just want to make outsiders and locals experience the ceramic culture.

Gaver saw affordances as possible actions afforded by an object [

29]. The realization of affordance requires actions at the organizational level [

33]. To realize the basic affordance, the company uses the tangible heritage and conducts protective restoration of the old factory buildings by focusing closely on the original functions of the industrial heritage. According to the basic affordance, the old industrial factories have been transformed into manufacturing and sale places for the ceramics industry, and the factory sites and open-air streets have been built into places to sell ceramic products independently created by young people in the “Spring and Autumn Fair” held twice a year. Additionally, to encourage the normalization of ceramic creation, a ceramic exhibition hall and shopping mall have been set up to enhance the participation of more young people interested in ceramic creation. With the development of various ceramic commercial activities, more than 9700 creative young people have registered their businesses in Taoxichuan. Many young makers come from renowned universities at home and abroad. The innovative drive and entrepreneurial potential of the young makers provide creative vitality and unique charm to Taoxichuan, thus realizing the basic affordance of the industrial heritage.

As an enterprise manager mentioned in the interview: “Does Jingdezhen have to rely on local ceramic workers with decades of experience and the ‘inheritors’ whose ceramic skills have been passed down from generation to generation to realize the transformation of the cultural and creative industry? From the perspective of Jingdezhen’s ceramic culture and creativity development in recent years, only young people from other places can truly activate Jingdezhen’s ceramic cultural resources and make them rejuvenate and vigor. In this way, our plants can be reused.”

The affordance realization can be short-term or long-term [

23]. Taoxichuan has realized the short-term affordance, that is, the recovery of enterprise capacity. Based on the context of ceramic culture, Taoxichuan has attracted numerous young makers to take advantage of its industrial heritage to develop the cultural and creative industries. In this way, Taoxichuan has achieved the basic affordance of ceramic making. However, in the past, after developing the original plant area into a cultural and creative park, some industrial heritage resources encountered the problems of weak development and the lack of development space in the late stages of development. Business managers found that this was caused the traditional culture that has little influence and does not have a strong customer base. Jingdezhen is home to Taoxichuan’s industrial heritage and has been the center of China’s ceramic production since ancient times. It is known worldwide as the “porcelain capital”. From ancient time till now, Jingdezhen has taken advantage of the Yangtze River to export porcelain and enjoyed the reputation of having artisans coming from all directions and the best porcelain in the world (Excerpted from “A Visit to Kiln People” written by Shen Huaicheng, a Chinese scholar in the early Qing Dynasty: Jingdezhen is famous for its fine porcelain, but it lacks artisans. Artisans come from all directions to produce the best porcelain in the world). These are the attributes of cultural transmission that the industrial heritage of Taoxichuan boasts. If we want to sustainably exploit industrial heritage resources, we need to attract more followers and create a context for disseminating ceramic culture.

4.3. Development and Utilization of Taoxichuan Industrial Heritage Resources to Achieve Sustainable Development of Enterprises

The perception of affordance is not only derived from the properties of the object, but also from the interrelationship between the person and the object [

33]. Therefore, based on the cultural identity of the industrial heritage created by the enterprise, the management of Taoxichuan has found that the factory building with essential manufacturing functions has attracted the widespread participation of numerous young artists, designers, and ceramic enthusiasts. The industrial heritage resources, such as architectural venues, are accessible and reusable, friendly to newcomers, especially young people, and can provide places for target groups to work, live, and learn. People can get artistic inspiration from the memories of the lives of traditional ceramic artisans. The enterprise believes that new artisans bring the possibility of reviving the ceramic industry in Taoxichuan. The characteristics of these abandoned factories and traditional memories are the cultural affordances of industrial heritage resources that can restore the ceramic industry. For example, young people can use waste factories to inspire creativity, thus creating various business forms based on ceramic culture. Additionally, they actively promote ceramic culture, which can be perceived as the dissemination affordance of the industrial heritage.

Currently, the identification of affordance remains highly relevant to the goal. Based on the cultural dissemination of the industrial heritage, the ceramic industry in Taoxichuan has been gradually revived due to the realization of the basic affordance of the industrial heritage. Through corporate brand publicity, enterprise managers have discovered that the essence of publicizing the brand is to introduce the traditional ceramic culture represented by the industrial heritage. These traditional cultures can trigger cultural identity and are easy to spread. Customers are interested in historical allusions related to ceramic production and willing to share their ceramic-making process or experience on social media. Enterprise managers deem it possible to expand their influence through traditional ceramic culture. For example, Jingdezhen, the home to Taoxichuan, is the earliest industrial city in the world and has many official kilns of various periods. The porcelain it produces is famous at home and abroad for the characteristics of “white as jade, thin as paper, bright as a mirror, and sound like a chime” (Used to describe bone china. Bone china is creamy white with soft luster. It is as warm and moist as jade; under the light, its porcelain glaze is smooth and crystal; when you gently knock it with the thumb and middle finger, it will sound like a musical instrument playing a beautiful melody. Bone china is described as paper-like porcelain because of how thin it is). The historical and cultural influence that industrial heritage resources possess is the dissemination affordance of industrial heritage resources.

Currently, affordance is more inclined to spread culture. In this case, enterprise managers create a cultural dissemination context based on industrial heritage resources and the identification with traditional ceramic culture. On the one hand, the management uses the characteristics of cultural dissemination to empower the business image and spread ceramic culture offline through the change of business image. For example, the management turns the young makers from ordinary stallholders at the market into “Yike” (Excerpted from “Yi Lin·Jing Zhi Sui” written by Jiao Gan, a scholar in the Han Dynasty: Pedestrians feared, Yike fled. Yike refers to people living in cities and towns) at the Yike Space Mall, creating a traditional cultural atmosphere and encouraging them to promote their ceramic culture. On the other hand, the management actively organizes various ceramic academic events, and regular cultural and art exhibitions to enhance the continued dissemination of ceramic culture. Additionally, to remove the time and geographical limitations with offline communication, the management created the platforms for online communication. The enterprise has established a website, opened a WeChat official account, developed Taoxichuan APP, and actively works with Tik Tok to conduct livestreaming to promote the ceramic culture of Taoxichuan. For instance, the Kiln Festival held in September 2020 attracted more than 150 high-quality merchants to participate offline, with more than 100 internet celebrities conducting livestreaming, achieving a sale of RMB 32.68 million. The enterprise managers of Taoxichuan created a context for disseminating ceramic culture. These contextual changes bring about changes in resource utilization. It is also consistent with the argument of the resource-based view of the firm that resources generate different performances depending on the context [

42].

As mentioned by the enterprise manager, due to the lack of recognition of the ceramic industry heritage in the past, plenty of ceramic industry heritage has not been effectively protected and revitalized. From another point of view, the best conservation of ceramic physical heritage and intangible cultural heritage is to integrate with life and modern science and technology, to spread ceramic culture.

At this stage, the long-term goal of affordance, namely the expansion of the industry, is achieved. To achieve the dissemination affordance, enterprises closely focus on the tangible and intangible culture reflected by industrial heritage. Based on the dissemination affordance of industrial heritage, all the corporate culture and memories of the times embedded in the buildings of the industrial heritage factory are retained and prominently displayed, highlighting the protection of cultural authenticity and memory of the times; relevant business guidance on heritage culture is provided to tenants to ensure high-quality dissemination of heritage culture. Additionally, veteran workers are invited to tell the history of the porcelain factory for the art community staff, young students, and residents of the surrounding communities to promote heritage culture. Since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, online communication has intensified. In February 2020, the activity “Taoxichuan Invites You to Visit Jingdezhen Ceramic Industry Heritage Museum” was launched, and the “Taoxichuan International Education Online Platform” In 2021, “Taoxichuan ‘COME FROM’ Online and Offline Forums” and other activities were held to enhance and expand the influence of heritage culture. Additionally, it is found that livestreaming and short video platforms can attract more attention and improve public awareness of ceramic culture, and the simultaneous livestreaming of interactive communication on the network greatly spreads the knowledge and culture of traditional ceramics, stimulates users’ cognition of traditional culture, forming a higher conversion rate of purchase. By transmitting the ceramic culture represented by the industrial heritage, Taoxichua inspires people to identify with the tangible and intangible culture of the industrial heritage and ultimately realizes the dissemination affordance of the industrial heritage.

As an enterprise manager in the interview states: “the cultural and brand values accumulated in the thousand-year of porcelain making in Jingdezhen and various tangible and intangible heritages related to the porcelain making scattered in Jingdezhen have not been fully excavated and effectively revitalized. However, we have effectively utilized the cultural value of Taoxichuan through various activities.”.

5. Discussion

How did Taoxichuan evoke its industrial heritage and achieve sustainable corporate development? Through the above analysis, the conclusions are as follows:

First, the key factor for evoking industrial heritage resources and realizing the sustainable development of enterprises is to create a new cultural context that identifies with the industrial heritage. How to evoke the value of resources, such as the industrial heritage? The existing industrial heritage development and utilization methods mainly focus on reproducing a retro style to attract customers [

43]. In fact, most of these discussions on the industrial heritage explore the transformation of tangible heritage [

16], with the assumption that the obsolescence of the industrial heritage resources by technological progress. The approach of restoring the retro style has been questioned by the academic community. Scholars point out that the process of simply commercializing industrial heritage only satisfies the current needs of people, that such needs are all one-sided choices based on people’s perceptions at the time [

44], and that it is a dilution and misunderstanding of industrial history [

45] and even the neglect of the intangible attributes of the industrial heritage resources [

46]. Hence, some scholars argue that the retro context has made the industrial heritage lose its historical and cultural significance [

14]. Moreover, the economic boost driven by this approach cannot last for a long time [

47]. In this study, we have found that the management creates new contexts of cultural identity that allow for dynamic interactions between people and resources, especially the culture embedded in the resources, thereby facilitating the perception and realization of the industrial heritage by companies and users. Specifically, when evoking the industrial resources of Taoxichuan, the enterprise creates a new context of traditional ceramic cultural identity, activating the tangible and intangible culture embedded in the industrial heritage. The cultural identity is integrated into the operation of the enterprise. Through digital tools, the power of cultural communication is amplified, evoking and amplifying the value of the ceramic industry represented by Taoxichuan, thus achieving sustainable development of enterprises.

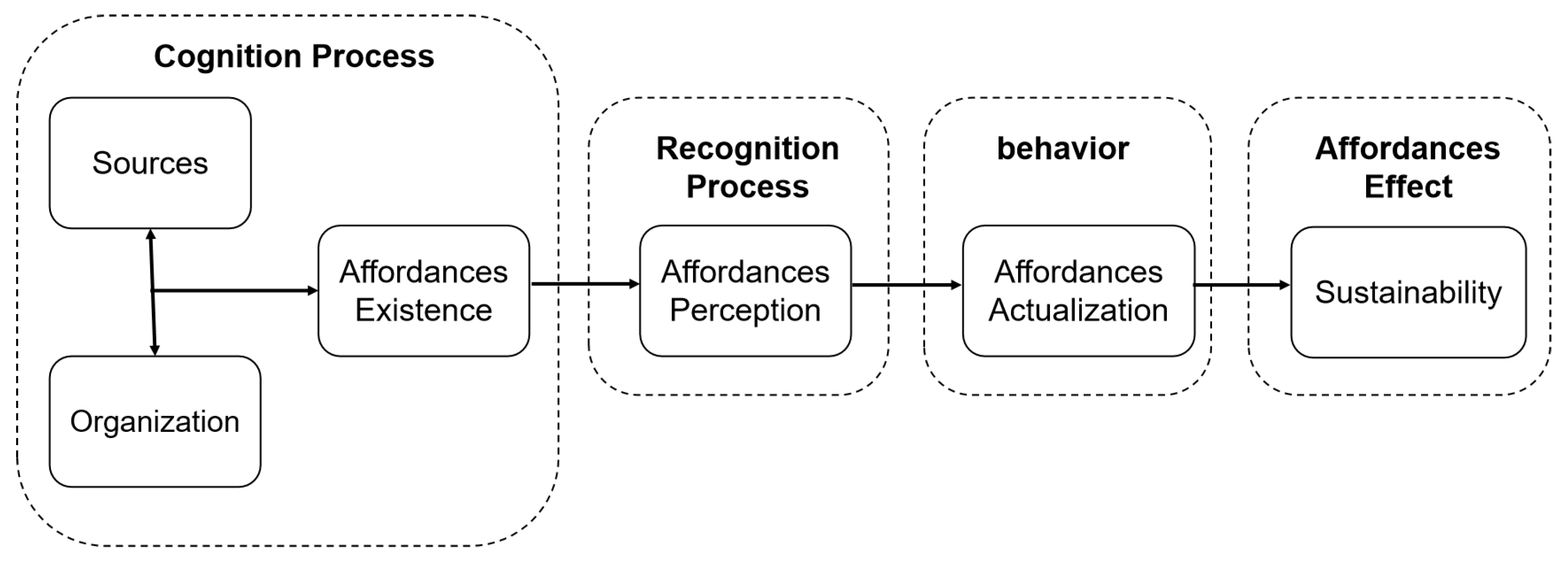

Second, the essence of evoking heritage resources is the development process of resource utilization methods from basic affordance to dissemination affordance. The evocation of the industrial heritage resources consists of two stages: (1) achieve the basic affordance of tangible culture; (2) realize the dissemination affordance of intangible culture (as shown in

Figure 3). It has been established that the sustainable development of industrial heritage can only be achieved by reusing the culture of the industrial heritage [

48]. However, few studies explore the translation of the industrial heritage culture into transferable value from the academic perspective, due to the fact that culture is an innovation based on human emotional guidance and construction [

49], and this innovation is driven by socio-cultural dynamics rather than techno-science [

50]. Eaton pointed out that culture does not directly provide action to create value but influences action by forming a “repertoire” [

51]. Thus, it can be seen that although scholars have found that it is the culture of the industrial heritage that performs a key innovative role in the sustainable development of the industrial heritage [

9], this conclusion cannot provide sufficient practical guidance on achieving sustainable development of industrial heritage or present a clear demonstration of evoking industrial heritage resources for sustainable development of enterprises from the academic perspective. Correspondingly, we can only propose technical suggestions, such as the use of digital technology [

52] or the approach of cultural integration [

53]. Through this study, we have found that enterprises can achieve sustainable development only when they realize the high-level affordance of the industrial heritage, that is, dissemination affordance. In conclusion, although the industrial heritage can no longer enables mass production, the heritage culture it contains can guide innovation. If intangible cultural heritage can only be transmitted as historical knowledge, it will not create value. Enterprise needs to discover ways to internalize historical culture into corporate culture and make it more easily accepted and spread by establishing a brand with the industrial heritage culture as its connotation and integrating cultural allusions with its actual operation. The key to realizing this affordance lies in that the management identifies the affordance of cultural dissemination, rather than just perceives the heritage resources as cultural relics resources to be protected. The dissemination affordance of the industrial heritage, which is different from the basic affordance of basic functions, is a high-level affordance. Through cultural dissemination, the enterprise actively interacts with consumers and reaches a consensus on cultural identity. Cultural identity leads to a higher conversion rate of purchase. Therefore, enterprises with the industrial heritage can achieve sustainable development.

Third, we should figure out the evolutionary mechanisms to evoke industrial heritage resources for sustainable corporate development. The existing research on the development and utilization of the industrial heritage mainly focuses on how to transform and utilize the factors affecting industrial heritage resources. Few scholars explore the evolutionary mechanism that drives the sustainable development of enterprises by developing and utilizing industrial heritage resources. It may lead to a dilemma that the professional conservation and development technologies are applied very successfully, but the enterprise lacks momentum for follow-up development and the ability to resist risks. Based on the affordance theory, we have proposed the “basic-amplification” development process of industrial heritage resources. The process emphasizes that the original context is an important factor limiting the evocation of the industrial heritage, and that the key to evoking the industrial heritage is to continuously explore and construct new contexts to realize the evolution of resource values from low to high, and that the main task of the management is not simply to reuse industrial heritage resources, but to identify and realize the affordance of these resources in new contexts.

We have found the authenticity and accessibility of the industrial heritage in the context of offline cultural identity, which lays a solid foundation for people to accept the traditional industrial culture and establish a unified cognitive context. However, constrained by the time, space, and number of customer groups of offline cultural dissemination, enterprises encounter issues, such as the inability to develop new customers and low dissemination efficiency. The online dissemination of Taoxichuan’s industrial heritage creates a new context for the spread of digital culture, making the dissemination of industrial heritage resources no longer limited by time and space. Industrial heritage resources can not only advance offline cultural identity and interaction, but also promote all-around online community interaction at any time and space through digital technology empowerment. By integrating cultural attributes with digital technologies, the management builds an interactive experience platform on the cloud, migrates the cultural attributes of industrial heritage resources to cyberspace, and gives full play to the important role of digitalization in amplifying cultural influence. The significant advantages of online-offline integration promote the interaction between the industrial heritage and customers, achieving high-value interactions across time and regions, and realizing sustainable corporate development.

6. Conclusions

When developing and utilizing industrial heritage resources, it is crucial to grasp an accurate understanding of the affordance of the industrial heritage. If the material and cultural functions of industrial heritage resources are not properly utilized, these historical resources will eventually decline. From the perspective of affordance theory, this paper examines the key factors in the development and utilization of industrial heritage resources, the implementation process, and the evolution mechanism, with an aim to providing operational guidance for enterprises to achieve “sustainable development and utilization”. It is found that the management has to create new contexts of cultural identity, cultural contexts suitable for the industrial heritage, that allow for dynamic interactions between people and resources, especially the culture embedded in the resources, thereby facilitating the cognition and realization of the industrial heritage by companies and users. Additionally, the evocation of the industrial heritage needs to go through the development process from low to high-level affordance of industrial heritage resources. The low-level affordance of the industrial heritage, such as the resumption of mass production is unrealistic under the current context. However, high-level affordance, such as the dissemination of heritage culture, can guide and build innovation. Only by realizing the high-level affordance of heritage resources, can we revoke industrial heritage resources. Finally, the actualization of the affordance of the industrial heritage from low to high-level enables enterprises engaged in the industrial heritage to achieve sustainable development. The low-level affordance (basic affordance) is valuable, rare, imperfectly imitable, and non-substitutable. They are the four characteristics that the resource-based view of the firm considers to be necessary for a company to achieve competitive advantages. The actualization of high-level affordance is conducive to spreading the industrial heritage culture, interacting with consumers, eventually reaching a consensus on cultural identity, and achieving a high purchase conversion rate and sustainable corporate development.

Although this paper constructs the process and mechanism model of activating industrial heritage resources, it has some limitations. For example, the research object is a traditional cultural company. We do not know whether the study applies to all companies with industrial heritage resources. The activation steps and methods may be adjusted or supplemented for different companies. In future research, it is necessary to explore other types of companies to obtain more generalized research findings.