Unleashing Employee Potential: A Mixed-Methods Study of High-Performance Work Systems in Bangladeshi Banks

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

3. The Historical and Cultural Context of Bangladeshi Banking Industry

4. The Literature

HPWS and Employee Performance

5. Hypotheses

5.1. HPWS and Psychological Empowerment

5.2. HPWS and Employee Trust

5.3. HPWS and Affective Commitment

6. Methodology

6.1. Measures

6.1.1. Perceived HPWS and EP

6.1.2. Attitudinal Outcomes

6.2. Multicollinearity, Common Method Variance, Reliability and Validity

7. Findings from the Qualitative Stage

8. Findings from the Quantitative Stage

8.1. Measurement and Factor Structures of the Latent Constructs

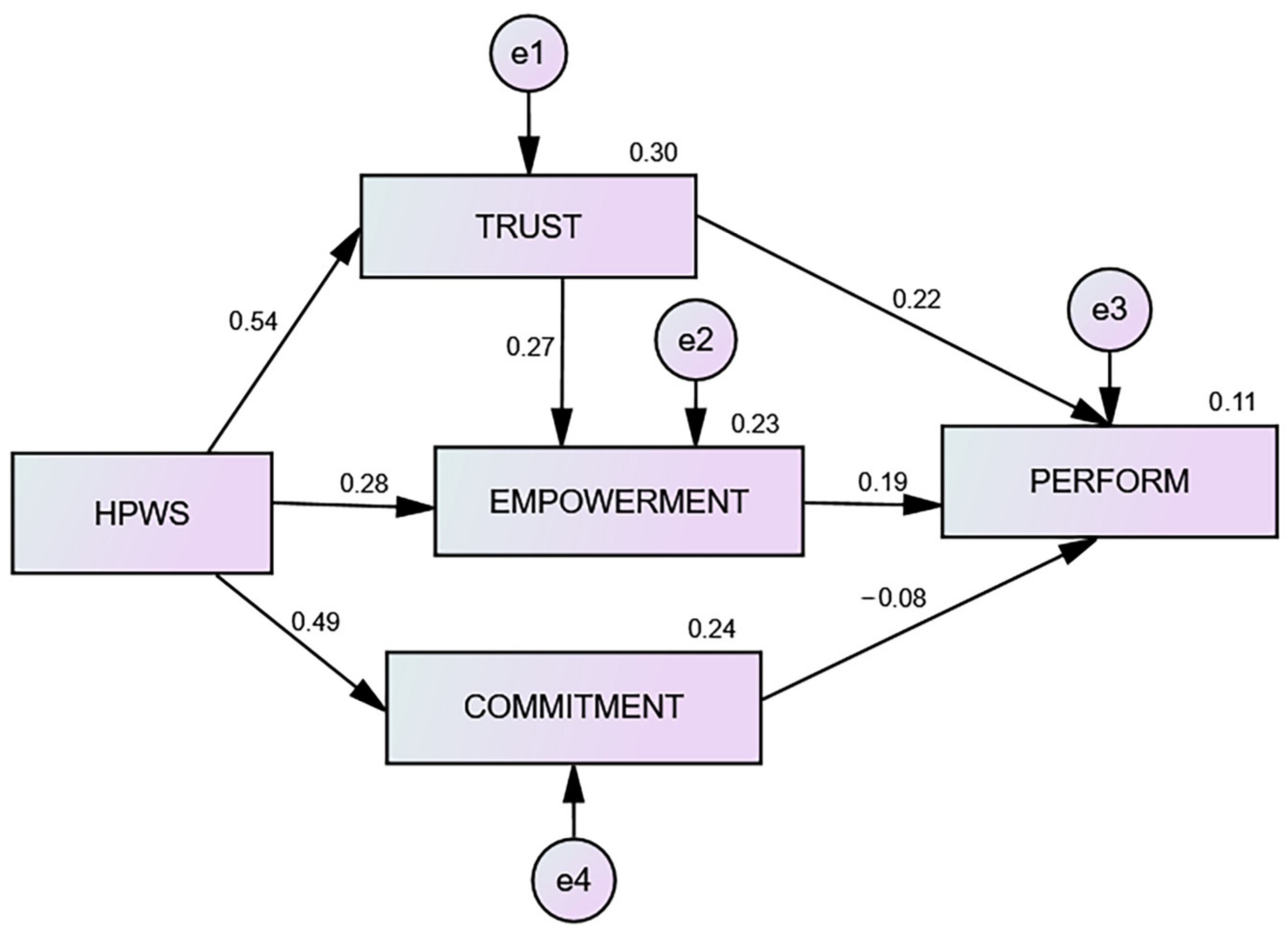

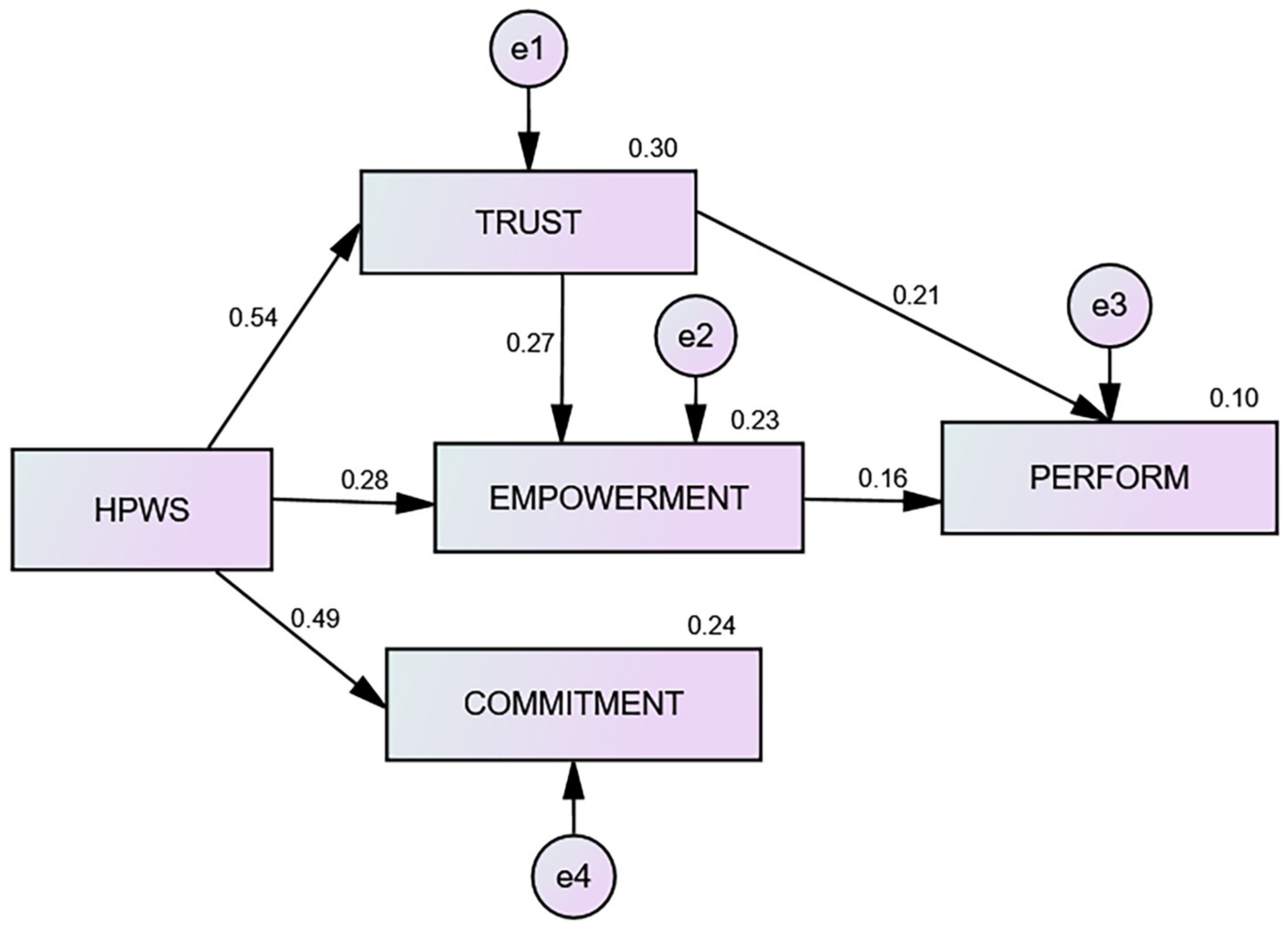

8.2. Testing the Hypothesised Causal Paths

9. Discussion

9.1. Influence of the Cultural Context of Bangladesh

9.2. The Black-Box of PHPWS–Performance Link in Bangladesh

10. Implications and Conclusions

10.1. Implications for the International HRD Research

10.2. Implications for the HRD Partitioners

10.3. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- Which HRM policies and practices are seen as important within your organisation? Are these practices uniformly and fairly applied to all employees?

- Do you think HR practices and policies are aligned with the organisation’s strategy? Do you think employees in your organisation generally view them as clearly linked to their personal goals?

- How do you think the HR policies and practices can be improved in your bank?

- How do you communicate and explain HR practices to both managers and employees? Do you think they are clearly understood by employees?

- Are the HR managers involved in the strategic decision making in your bank? How much authority do you think the HR division has over deciding HR practices and performance outcomes?

- Do you think the HR staff or the managers in your bank have adequate power, skills and resources to link an individual’s rewards with their performance or behaviour in a consistent and timely manner in your bank?

- Do you measure the effectiveness of different HR practices and policies in your bank? How?

- Do you think there are counterproductive or contradictory HR practices in your bank? Intended finding from interview schedule question 20: consistent HR messages.

- Are the employees allowed and encouraged to participate in the HR- or outcome-related decision-making process?

References

- Metcalfe, B.D.; Rees, C.J. Theorizing advances in international human resource development. Hum. Resour. Dev. Int. 2005, 8, 449–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kehoe, R.R.; Wright, P.M. The Impact of High-Performance Human Resource Practices on Employees’ Attitudes and Behaviors. J. Manag. 2013, 39, 366–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepak, D.P.; Liao, H.; Chung, Y.; Harden, E.E. A Conceptual Review of Human Resource Management Systems in Strategic Human Resource Management Research. Res. Pers. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2006, 25, 217–271. [Google Scholar]

- Boxall, P.; Ang, S.H.; Bartram, T. Analysing the ‘Black Box’ of HRM: Uncovering HR Goals, Mediators, and Outcomes in a Standardized Service Environment. J. Manag. Stud. 2011, 48, 1504–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boxall, P.; Macky, K. Research and Theory on High-Performance Work Systems: Progressing the High-Involvement Stream. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2009, 19, 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgar, F.; Geare, A. An Employee-Centred Analysis: Professionals’ Experiences and Reactions to HRM. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2014, 25, 673–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorta-Afonso, D.; González-de-la-Rosa, M.; Garcia-Rodriguez, F.J.; Romero-Domínguez, L. Effects of high-performance work systems (HPWS) on hospitality employees’ outcomes through their organizational commitment, motivation, and job satisfaction. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garavan, T.; McCarthy, A.; Carbery, R. International HRD: Context, processes and people–introduction. In Handbook of International Human Resource Development; Edward Elgar Publishing: Northampton, MA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh, R. Inviting Contributions on International HRD Research in HRDI; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Alagaraja, M. HRD and HRM perspectives on organizational performance: A review of literature. Hum. Resour. Dev. Rev. 2013, 12, 117–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piwowar-Sulej, K. Core functions of Sustainable Human Resource Management. A hybrid literature review with the use of H-Classics methodology. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 29, 671–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appelbaum, E.; Bailey, T.; Berg, P.; Kalleberg, A.L. Manufacturing Advantage: Why High-Performance Work Systems Pay Off; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, S.; Schuler, R. Understanding Human Resource Management in the Context of Organizations and Their Environments. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 1995, 46, 237–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, S.E.; Schuler, R.S.; Rivero, J.C. Organizational Characteristics as Predictors of Personnel Practices. Pers. Psychol. 1989, 42, 727–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Farooque, O.; Van Zijl, T.; Dunstan, K.; Karim, A.W. Corporate Governance in Bangladesh: Link between Ownership and Financial Performance. Corp. Gov. Int. Rev. 2007, 15, 1453–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Farooque, O.; Van Zijl, T.; Dunstan, K.; Karim, A.W. Ownership Structure and Corporate Performance: Evidence from Bangladesh. Asia-Pac. J. Account. Econ. 2007, 14, 127–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schick, A. Why Most Developing Countries Should Not Try New Zealand’s Reforms. World Bank Res. Obs. 1998, 13, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahajan, V.; Banga, K. The 86 Percent Solution: How to Succeed in the Biggest Market Opportunity of the Next 50 Years; Pearson Education: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, S.I.; Bartram, T.; Cavanagh, J.; Hossain, M.S.; Akter, S. “Decent work” in the ready-made garment sector in Bangladesh: The role for ethical human resource management, trade unions and situated moral agency. Pers. Rev. 2019, 48, 40–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabl, T.; Jayasinghe, M.; Gerhart, B.; Kühlmann, T.M. A meta-analysis of country differences in the high-performance work system–business performance relationship: The roles of national culture and managerial discretion. J. Appl. Psychol. 2014, 99, 1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bae, J.; Lawler, J. Organizational and HRM Strategies in Korea: Impact on Firm Performance in an Emerging Economy. Acad. Manag. J. 2000, 43, 502–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawler, J.J.; Chen, S.; Wu, P.C.; Bae, J.; Bai, B. High-Performance Work Systems in Foreign Subsidiaries of American Multinationals: An Institutional Model. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2010, 42, 202–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, P.M. Social exchange. Int. Encycl. Soc. Sci. 1968, 7, 452–457. [Google Scholar]

- Messersmith, J.G.; Patel, P.C.; Lepak, D.P. Unlocking the Black Box: Exploring the Link between High-Performance Work Systems and Performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 2011, 96, 1105–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cropanzano, R.; Mitchell, M.S. Social Exchange Theory: An Interdisciplinary Review. J. Manag. 2005, 31, 874–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piening, E.P.; Baluch, A.M.; Salge, T.O. The Relationship between Employees’ Perceptions of Human Resource Systems and Organizational Performance: Examining Mediating Mechanisms and Temporal Dynamics. J. Appl. Psychol. 2013, 98, 926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werner, S. High performance work systems in the global context: A commentary essay. J. Bus. Res. 2011, 64, 919–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousseau, D.; Schalk, R. Psychological Contracts in Employment: Cross-National Perspectives; Sage Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Shore, L.M.; Coyle-Shapiro, J.A.M. New Developments in the Employee–Organization Relationship. J. Organ. Behav. 2003, 24, 443–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ITIM International. 2016. Available online: https://geert-hofstede.com/bangladesh.html (accessed on 1 December 2019).

- Chowdhury, S.D.; Mahmood, M.H. Societal Institutions and HRM Practices: An Analysis of Four European Multinational Subsidiaries in Bangladesh. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2012, 23, 1808–1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huque, A.S. Accountability and Governance: Strengthening Extra-Bureaucratic Mechanisms in Bangladesh. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2011, 60, 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, A.E. New Public Management in Developing Countries: An Analysis of Success and Failure with Particular Reference to Singapore and Bangladesh. Int. J. Public Sect. Manag. 2006, 19, 180–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alavi, H. The State in Post-colonial Societies: Pakistan and Bangladesh. New Left Rev. 1972, 74, 59–81. [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill, J.; Wilson, D.; Purushothaman, R.; Stupnytska, A. How Solid Are the BRICs; Global Economics Paper No: 134; Goldman Sachs: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- PwC. The World in 2050: Will the Shift in Global Economic Power Continue? PricewaterhouseCoopers: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- International Monatory Fund. 2019. Available online: https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/NGDP_RPCH@WEO/OEMDC/ADVEC/WEOWORLD/BGD (accessed on 10 December 2019).

- Sobhan, R. The Political Economy of the State and Market in Bangladesh. Bangladesh J. Political Econ. 2002, 17, 19–33. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmood, M.; Nurul Absar, M.M. Human resource management practices in Bangladesh: Current scenario and future Challenges. South Asian J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2015, 2, 171–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reaz, M.; Arun, T. Corporate Governance In Developing Economies: Perspective from the Banking Sector in Bangladesh. J. Bank. Regul. 2006, 7, 94–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelati, W.; Dunn, J.; Lueth, E.; Kinoshita, N.; Alichi, A.; Perone, P. Bangladesh: Selected Issues (Approved by the Asia and Pacific Department, Trans.); IMF Country Report; International Monetary Fund: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bangladesh Bank. 2013. Available online: www.bangladesh-bank.org/ (accessed on 1 December 2014).

- Siddiqi, K.O. Interrelations between Service Quality Attributes, Customer Satisfaction and Customer Loyalty in the Retail Banking Sector in Bangladesh. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2011, 6, 12–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, N.; Wakabayashi, M.; Chen, Z. The Strategic HRM Configuration for Competitive Advantage: Evidence from Japanese Firms in China and Taiwan. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2003, 20, 447–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, I.H.; Huang, J.C.; Liu, S. Strategic HRM in China: Configurations and Competitive Advantage. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2008, 47, 687–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, E.; Dill, J.; Morgan, J.C.; Konrad, T.R. A Configurational Approach to the Relationship between High-Performance Work Practices and Frontline Health Care Worker Outcomes. Health Serv. Res. 2012, 47, 1460–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartram, T.; Casimir, G.; Djurkovic, N.; Leggat, S.G.; Stanton, P. Do Perceived High Performance Work Systems Influence the Relationship between Emotional Labour, Burnout and Intention to Leave? A Study of Australian Nurses. J. Adv. Nurs. 2012, 68, 1567–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, H.; Toya, K.; Lepak, D.; Hong, Y. Do They See Eye To Eye? Management and Employee Perspectives of High-Performance Work Systems and Influence Processes on Service Quality. J. Appl. Psychol. 2009, 94, 371–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeffer, J. Seven Practices of Successful Organizations. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1998, 40, 97–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacharatos, A.; Barling, J.; Iverson, R.D. High-Performance Work Systems and Occupational Safety. J. Appl. Psychol. 2005, 90, 77–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, H.-A.; Chiang, Y.-H.; Hsu, C.-C. High performance work system and HCN performance. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 540–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harley, B.; Allen, B.; Sargent, L. High Performance Work Systems and Employee Experience of Work in the Service Sector: The Case of Aged Care. Br. J. Ind. Relat. 2007, 45, 607–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallie, D.; Zhou, Y.; Felstead, A.; Green, F. Teamwork, Skill Development and Employee Welfare. Br. J. Ind. Relat. 2012, 50, 23–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilman, M.; Raby, S. National Context as a Predictor of High-Performance Work System Effectiveness in Small-to-Medium-Sized Enterprises (SMEs): A UK–French Comparative Analysis. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2013, 24, 372–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubel, M.R.B.; Rimi, N.N.; Walters, T. Roles of emerging HRM and employee commitment: Evidence from the banking industry of Bangladesh. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2017, 18, 876–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, M.F. Performance Management Practices in Organizations Operating in Bangladesh: A Deeper Examination. World Rev. Bus. Res. 2011, 1, 153–167. [Google Scholar]

- Absar, M.M.N. Recruitment and Selection Practices in Manufacturing Firms in Bangladesh. Indian J. Ind. Relat. 2012, 47, 436–449. [Google Scholar]

- Faruque, A. Current Status and Evolution of Industrial Relations System in Bangladesh. International Labor Organization. 2009. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/newdelhi/whatwedo/publications/WCMS_123336/lang--en/index.htm (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Haque, A.; Rahman, S.; Hussain, M. Factors Influencing Employee Performance in the Organization: An Exploratory Study of Private Organization in Bangladesh. Int. J. Contemp. Bus. Stud. 2011, 2, 25–53. [Google Scholar]

- Spreitzer, G.M. Psychological Empowerment in the Workplace: Dimensions, Measurement, and Validation. Acad. Manag. J. 1995, 38, 1442–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peccei, R.; Rosenthal, P. Delivering Customer Oriented Behaviour through Empowerment: An Empirical Test of HRM Assumptions. J. Manag. Stud. 2001, 38, 831–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wall, T.D.; Martin, R. Job and Work Design; John Wiley and Sons: Oxford, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Vandenberg, R.J.; Richardson, H.A.; Eastman, L.J. The impact of high involvement work processes on organizational effectiveness: A second-order latent variable approach. Group Organ. Manag. 1999, 24, 300–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arefin, M.S.; Alam, M.S.; Islam, M.R.; Rahaman, M. High-performance work systems and job engagement: The mediating role of psychological empowerment. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2019, 6, 1664204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, D.E.; Lawler, E.E. The Empowerment of Service Workers: What, Why, How, and When. In Managing Innovation and Change; Mayle, D., Ed.; SAGE Publications Limited: London, UK, 2006; pp. 155–169. [Google Scholar]

- Boxall, P.; Purcell, J.; Wright, P. The Oxford Handbook of Human Resource Management; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Godard, J. A Critical Assessment of the High-Performance Paradigm. Br. J. Ind. Relat. 2004, 42, 349–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, D.E. Human Resource Management and Performance: A Review and Research Agenda. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 1997, 8, 263–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, W.C.; Holmes, M.R. Impacts of employee empowerment and organizational commitment on workforce sustainability. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liden, R.C.; Wayne, S.J.; Sparrowe, R.T. An examination of the mediating role of psychological empowerment on the relationships between the job, interpersonal relationships, and work outcomes. J. Appl. Psychol. 2000, 85, 407–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casimir, G.; Waldman, D.A.; Bartram, T.; Yang, S. Trust and the Relationship between Leadership and Follower Performance: Opening the Black Box in Australia and China. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2006, 12, 68–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.C.; Chen, X.-P.; Meindl, J.R. How Can Cooperation be Fostered? The Cultural Effects of Individualism-Collectivism. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1998, 23, 285–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, R.C.; Davis, J.H.; Schoorman, F.D. An Integrative Model of Organizational Trust. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 709–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKnight, D.H.; Cummings, L.L.; Chervany, N.L. Initial Trust Formation in New Organizational Relationships. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1998, 23, 473–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, J.; Wall, T. New Work Attitude Measures of Trust, Organizational Commitment and Personal Need Non-Fulfilment. J. Occup. Psychol. 1980, 53, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paauwe, J. HRM and Performance: Achieving Long-term Viability; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Paauwe, J.; Richardson, R. Introduction. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 1997, 8, 257–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appelbaum, E.; Bailey, T.; Berg, P.; Kalleberg, A. Do High Performance Work Systems Pay Off? In The Transformation of Work (Research in the Sociology of Work, Volume 10); Vallas, S., Ed.; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2001; pp. 85–107. [Google Scholar]

- Macky, K.; Boxall, P. The Relationship Between ‘High-Performance Work Practices’ and Employee Attitudes: An Investigation of Additive and Interaction Effects. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2007, 18, 537–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitener, E.M. Do “High Commitment” Human Resource Practices Affect Employee Commitment? A Cross-Level Analysis Using Hierarchical Linear Modeling. J. Manag. 2001, 27, 515–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laschinger, H.; Finegan, J. Using Empowerment to Build Trust and Respect in the Workplace: A Strategy for Addressing the Nursing Shortage. Nurs. Econ. 2005, 23, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Laschinger, H.K.S.; Finegan, J.; Shamian, J. The Impact of Workplace Empowerment, Organizational Trust on Staff Nurses’ Work Satisfaction and Organizational Commitment. Health Care Manag. Rev. 2001, 26, 7–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laschinger, H.K.S.; Finegan, J.; Shamian, J.; Casier, S. Organizational Trust and Empowerment in Restructured Healthcare Settings: Effects on Staff Nurse Commitment. J. Nurs. Adm. 2000, 30, 413–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouzes, J.M.; Posner, B.Z. The Credibility Factor: What Followers Expect From Their Leaders. Manag. Rev. 1990, 79, 29–33. [Google Scholar]

- Imam, H.; Naqvi, M.B.; Naqvi, S.A.; Chambel, M.J. Authentic leadership: Unleashing employee creativity through empowerment and commitment to the supervisor. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2020, 41, 847–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, K.B.; Kang, S.-W.; Choi, S.B. Empowering leadership, risk-taking behavior, and employees’ commitment to organizational change: The mediated moderating role of task complexity. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.P.; Allen, N.J. A three-component conceptualization of organizational commitment. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 1991, 1, 61–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suliman, A.M. Is it really a mediating construct? The mediating role of organizational commitment in work climate-performance relationship. J. Manag. Dev. 2002, 21, 170–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.I. Does affective commitment positively predict employee performance? Evidence from the banking industry of Bangladesh. J. Dev. Areas 2015, 49, 429–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, A.; Khan, S.I. Promoting meaningfulness in work for higher job satisfaction: Will intent to quit make trouble for business managers? J. Organ. Eff. People Perform. 2023, 10, 455–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.P.; Allen, N.J.; Smith, C.A. Commitment to organizations and occupations: Extension and test of a three-component conceptualization. J. Appl. Psychol. 1993, 78, 538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riketta, M. Attitudinal organizational commitment and job performance: A meta-analysis. J. Organ. Behav. 2002, 23, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Mixed Methods Research: Are the Methods Genuinely Integrated or Merely Parallel. Res. Sch. 2006, 13, 41–47. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, R.L.; Reilly, T.M.; Creswell, J.W. Methodological Rigor in Mixed Methods: An Application in Management Studies. J. Mix. Methods Res. 2020, 14, 473–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OSIRIS. 2011. Available online: http://eps.bvdep.com/en/OSIRIS.html (accessed on 19 January 2012).

- OSIRIS. 2011. Available online: http://www.lib.nus.edu.sg/ecoll/db/osiris_data.pdf (accessed on 19 January 2012).

- BvDEP. Ownership Database. Available online: https://www.bvdinfo.com/en-gb/ (accessed on 1 January 2013).

- Legard, R.; Keegan, J.; Ward, K. Qualitative Research Practice: A Guide for Social Science Students and Researchers; Ritchie, J., Lewis, J., Eds.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bartram, T.; Stanton, P.; Leggat, S.; Casimir, G.; Fraser, B. Lost in Translation: Exploring the Link between HRM and Performance in Healthcare. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2007, 17, 21–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Moorman, R.H.; Fetter, R. Transformational Leader Behaviors and Their Effects on Followers’ Trust in Leader, Satisfaction, and Organizational Citizenship Behaviors. Leadersh. Q. 1990, 1, 107–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schindler, P.L.; Thomas, C.C. The Structure of Interpersonal Trust in the Workplace. Psychol. Rep. 1993, 73, 563–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. SPSS and SAS Procedures for Estimating Indirect Effects in Simple Mediation Models. Behav. Res. Methods 2004, 36, 717–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended Fremedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farrell, A.M.; Rudd, J.M. Factor Analysis and Discriminant Validity: A Brief Review of Some Practical Issues. In ANZMAC 2009 Conference Proceedings; Dewi, T., Ed.; ANZMAC: Carlton, VIC, Australia, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modeling with AMOS: Basic Concepts, Programming, and Applications; Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hoe, S.L. Issues and Procedures in Adopting Structural Equation Modeling Technique. J. Appl. Quant. Methods 2008, 3, 76–83. [Google Scholar]

- Bartram, T. People Management Configurations: A Population Ecology Approach. Manag. Res. News 2011, 34, 663–677. [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Alcazar, F.; Romero-Fernandez, P.M.; Sanchez-Gardey, G. Strategic Human Resource Management: Integrating the Universalistic, Contingent, Configurational and Contextual Perspectives. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2005, 16, 633–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishii, L.H.; Lepak, D.P.; Schneider, B. Employee Attributions of the “Why” of HR Practices: Their Effects on Employee Attitudes and Behaviors, and Customer Satisfaction. Pers. Psychol. 2008, 61, 503–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmeli, A.; Spreitzer, G.M. Trust, Connectivity, and Thriving: Implications for Innovative Behaviors at Work. J. Creat. Behav. 2008, 43, 169–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, R.; Chen, G.; Lepak, D. Through the Looking Glass of a Social System: Cross-Level Effects of High-Performance Work Systems on Employee’s Attitudes. Pers. Psychol. 2009, 62, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.H. Patron-Client Networks and the Economic Effects of Corruption in Asia. Eur. J. Dev. Res. 1998, 10, 15–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDuffie, J. Human Resource Bundles and Manufacturing Performance: Organizational Logic and Flexible Production Systems in The World Auto Industry. Ind. Labor Relat. Rev. 1995, 48, 197–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; McLean, G.N. The dilemma of defining international human resource development. Hum. Resour. Dev. Rev. 2007, 6, 96–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alagaraja, M. Mobilizing organizational alignment through strategic human resource development. Hum. Resour. Dev. Int. 2013, 16, 74–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartram, T.; Karimi, L.; Stanton, P.; Leggat, S. Social Identification: The Role of High Performance Work Systems and Empowerment. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2014, 25, 2401–2419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, P.M.; Nishii, L.H. Strategic HRM and Organizational Behavior: Integrating Multiple Levels of Analysis; CAHRS Working Paper Series; Center for Advanced Human Resource Studies, Cornell University: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 4–24. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, A.P.; James, L.R.; Bruni, J.R. Perceived Leadership Behavior and Employee Confidence in the Leader as Moderated by Job Involvement. J. Appl. Psychol. 1975, 60, 146–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, J.; Morrissey, M.A. Trust in Employee/Employer Relationships: A Survey of West Michigan Managers. Public Pers. Manag. 1990, 19, 443–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Labels (Observed Items) | Questionnaire Items |

|---|---|

| Psychological Empowerment (PE) | |

| EMPOWER1 | The work I do is very important to me |

| EMPOWER4 | I am confident about my ability to do my job |

| EMPOWER7 | I have significant autonomy in determining how I do my job |

| EMPOWER10 | My impact on what happens in this unit is large |

| Employee Trust (ET) | |

| TRUST1 | I am confident that I will always receive fair treatment from my line supervisor |

| TRUST4 | The person to whom I report directly can be relied on to look after my best interests |

| TRUST5 | I feel a strong sense of loyalty toward the person to whom I report directly |

| Selective Hiring | |

| RECRUIT1 | Recruitment and selection are impartial |

| RECRUIT3 | Interview panels are used for selection |

| RECRUIT5 | Appointments are merit-driven |

| Performance Management | |

| PERFORMGT2 | Performance is reviewed against agreed goals and organisation-wide requirements with customised personal feedback |

| PERFORMGT3 | A PMS is in place to ensure that staff are competent and accountable |

| PERFORMGT5 | In this unit, the statements of accountabilities and responsibilities are regularly reviewed to ensure that they are relevant to the current organisational needs and goals |

| Extensive Training | |

| TRAINING1 | Providing employees with training beyond that mandated by government regulations is a priority in this unit |

| TRAINING6 | Ample opportunity to discuss training requirements with my line supervisor |

| TRAINING7 | Organisation pays for any work-related training and development |

| Leadership style of immediate manager | My immediate supervisor: |

| IMMEMGT2 | encourages employees to come up with their own solutions and suggestions |

| IMMEMGT5 | encourages employees to express ideas and opinions |

| IMMEMGT6 | provides continuous encouragement |

| Self-managed Team | |

| TEAM1 | The development of teams is important |

| TEAM3 | Employee suggestions are implemented |

| TEAM4 | Decision making by non-managerial staffs is encouraged |

| Pay Equity | |

| PAY1 | Adequate pay to all |

| PAY2 | Equitable pay to all |

| PAY3 | Adequate pay for me |

| PERFORM | Supervisor’s rating of individual employee performance |

| “Perceived HPWS” Components | Number of Participants that Mentioned the HR Practice | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Pay Equity | 15 | Most participants mentioned the first six HR practices as desirable. For example, a Bank B manager stated: “we must focus on HR policy and practices because this sector in Bangladesh is highly competitive and without good HR practices we cannot attract or retain good people or remain competitive” (BB 2). This statement indicates the importance of selective recruitment and the retention of talent, which the respondent suggested can be achieved by fair performance management, extensive training, good leadership, competitive pay packages and empowerment through teamwork. The HR manager of Bank A said, “hiring, development, pay, retirement benefits are important factors in this industry. Mostly the fair recruitment plus development opportunities must be ensured” (BA 2). Another Bank A manager (BA 7) mentioned fair recruitment and training and development as sources of motivation and commitment. Profit bonus, employee welfare programs, interest-free or reduced-interest home loans and mentoring are mentioned as good PMSs. Many emphasise the supportive leadership of the manager. Based on similar findings from many other respondents, these six items are retained as “Perceived HPWS” measures. |

| Selective hiring | 14 | |

| Performance management | 13 | |

| Extensive training | 13 | |

| Immediate Manager’s leadership style | 10 | |

| Self-managed team | 7 | |

| Information Sharing | None mentioned it voluntarily | When asked, many respondents viewed a high level of information sharing as inefficient in terms of time, cost and outcome considerations. Top management’s information privileges were generally supported by all levels of employees, as they saw the value of confidentiality and the sensitivity of the information. |

| Job security | Two respondents said job should not be too secured as employees tend to perform less if they feel secured in job. | The employees from the high-performing bank did not express any job insecurity, nor did they demand more assurance for that. They rather expressed self-efficacy about their capability to ensure a new placement in another bank due to their high level of individual performance. In contrast, the employees from the average-performing bank felt no risk of losing their jobs in their respective organisation due to the support from their influential informal internal or external referees. Those who were recruited and selected systematically in Bank B viewed this confidence in informally recruited and secured non-performers as a deterrent to the bank’s performance. |

| Job quality | None raised this issue voluntarily | Job quality is generally perceived by the respondents as fairly standard in Bangladeshi banks, making no difference to their commitment or individual performance. |

| Reduced Status distinction | None raised this voluntarily | Reduced status distinction is not perceived as desirable to the respondents. When asked by the interviewer, one respondent from Bank A said, “certain distance should be maintained between the senior and junior employees to ensure efficiency and decorum” (BA 4). In Bank B one participant employee said, “Junior employees feel motivated to work better to reach the higher position as we look up to the boss or managers. If they maintain a similar status, there is nothing to look up to” (BB 6). This phenomenon can be explained by the high-power distance dimension embedded in the Bangladeshi culture. |

| (A) | ||||||||

| Labels (Observed Items) | Cronbach’s Alpha | Std. Regression Weight | SMC | |||||

| Psychological Empowerment | 0.840 | |||||||

| EMPOWER1 | 0.766 | 0.587 | ||||||

| EMPOWER2 | 0.826 | 0.683 | ||||||

| EMPOWER3 | 0.785 | 0.616 | ||||||

| EMPOWER4 | 0.694 | 0.482 | ||||||

| EMPOWER5 | 0.751 | 0.564 | ||||||

| EMPOWER6 | 0.543 | 0.295 | ||||||

| EMPOWER7 | 0.716 | 0.512 | ||||||

| EMPOWER8 | 0.731 | 0.535 | ||||||

| EMPOWER9 | 0.777 | 0.604 | ||||||

| EMPOWER10 | 0.830 | 0.690 | ||||||

| EMPOWER11 | 0.651 | 0.424 | ||||||

| EMPOWER12 | 0.639 | 0.409 | ||||||

| Employee Trust | 0.839 | |||||||

| TRUST1 | 0.779 | 0.606 | ||||||

| TRUST2 | 0.641 | 0.411 | ||||||

| TRUST3 | 0.867 | 0.751 | ||||||

| TRUST4 | 0.827 | 0.683 | ||||||

| TRUST5 | 0.757 | 0.574 | ||||||

| TRUST6 | 0.800 | 0.641 | ||||||

| TRUST7 | 0.497 | 0.247 | ||||||

| Affective Commitment | 0.709 | |||||||

| COMMIT1 | 0.692 | 0.478 | ||||||

| COMMIT2 | 0.728 | 0.531 | ||||||

| COMMIT3 | 0.528 | 0.279 | ||||||

| COMMIT7 | 0.472 | 0.222 | ||||||

| RCOMMIT5 | 0.829 | 0.688 | ||||||

| RCOMMIT6 | 0.783 | 0.613 | ||||||

| RCOMMIT8 | 0.560 | 0.314 | ||||||

| Selective Hiring | 0.813 | |||||||

| RECRUIT2 | 0.589 | 0.347 | ||||||

| RECRUIT3 | 0.466 | 0.217 | ||||||

| RECRUIT5 | 0.828 | 0.686 | ||||||

| RECRUIT6 | 0.771 | 0.594 | ||||||

| RECRUIT7 | 0.750 | 0.563 | ||||||

| Performance Management | 0.903 | |||||||

| PERFORMGT1 | 0.618 | 0.381 | ||||||

| PERFORMGT2 | 0.790 | 0.624 | ||||||

| PERFORMGT3 | 0.891 | 0.794 | ||||||

| PERFORMGT4 | 0.921 | 0.848 | ||||||

| PERFORMGT5 | 0.834 | 0.696 | ||||||

| Extensive Training | 0.884 | |||||||

| TRAINING1 | 0.613 | 0.376 | ||||||

| TRAINING5 | 0.830 | 0.690 | ||||||

| TRAINING6 | 0.775 | 0.601 | ||||||

| TRAINING7 | 0.590 | 0.348 | ||||||

| TRAINING8 | 0.793 | 0.628 | ||||||

| Management/Leadership Style of the Immediate Manager | 0.949 | |||||||

| IMMEMGT1 | 0.834 | 0.696 | ||||||

| IMMEMGT2 | 0.865 | 0.748 | ||||||

| IMMEMGT3 | 0.856 | 0.733 | ||||||

| IMMEMGT4 | 0.820 | 0.673 | ||||||

| IMMEMGT5 | 0.879 | 0.773 | ||||||

| IMMEMGT6 | 0.877 | 0.770 | ||||||

| IMMEMGT7 | 0.836 | 0.698 | ||||||

| Self-managed Team | 0.739 | |||||||

| TEAM1 | 0.588 | 0.345 | ||||||

| TEAM2 | 0.877 | 0.769 | ||||||

| TEAM3 | 0.690 | 0.476 | ||||||

| TEAM4 | ||||||||

| Pay Equity | 0.904 | |||||||

| PAY1 | 0.915 | 0.838 | ||||||

| PAY2 | 0.835 | 0.697 | ||||||

| PAY3 | 0.861 | 0.742 | ||||||

| (B) | ||||||||

| Latent Constructs | CR | AVE | MSV | ASV | TRUST | HPWS | EMPOWERMENT | COMMITMENT |

| TRUST | 0.897 | 0.559 | 0.413 | 0.298 | 0.748 | |||

| HPWS | 0.805 | 0.511 | 0.340 | 0.317 | 0.529 | 0.715 | ||

| EMPOWERMENT | 0.863 | 0.520 | 0.501 | 0.415 | 0.643 | 0.575 | ||

| COMMITMENT | 0.65 | 0.512 | 0.325 | 0.230 | 0.380 | 0.570 | 0.471 | 0.716 |

| (A) | |||||

| Items | HPWS | TRUST | EMPOWERMENT | COMMITMENT | PERFORM |

| HPWS | 1.000 | ||||

| TRUST | 0.544 | 1.000 | |||

| EMPOWERMENT | 0.426 | 0.420 | 1.000 | ||

| COMMITMENT | 0.495 | 0.269 | 0.211 | 1.000 | |

| PERFORM | 0.181 | 0.273 | 0.249 | 0.089 | 1.000 |

| (B) | |||||

| Hypotheses | Two-tailed significance (BC) of direct or indirect effects (95% confidence) | ||||

| H1a | p = 0.001 (direct effect) Hypothesis accepted | ||||

| H1b | p = 0.001 (indirect effect) Hypothesis accepted | ||||

| H2a | p = 0.001 (direct effect) Hypothesis accepted | ||||

| H2b | p = 0.001 (indirect effect) Hypothesis accepted | ||||

| H2c | p = 0.001 (indirect effect) Hypothesis accepted | ||||

| H2d | p = 0.001 (indirect effect) Hypothesis accepted | ||||

| H3a | p = 0.001 (direct effect) Hypothesis accepted | ||||

| H3b | p = 0. 581 (indirect effect) Hypothesis rejected | ||||

| PAY | TEAM | TRAINING | IMMEMGT | PERFORM GT | RECRUIT | IMPACT | SELF DETERMINATION | COMPETENCE | MEANING | NEGETIVE ARTEFACT | AFFECTIVE COMPONENT | PERFORM | TRUST | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PAY | 1.000 | |||||||||||||

| TEAM | 0.379 | 1.000 | ||||||||||||

| TRAINING | 0.384 | 0.714 | 1.000 | |||||||||||

| IMMEMGT | 0.262 | 0.581 | 0.599 | 1.000 | ||||||||||

| PERFORM GT | 0.342 | 0.638 | 0.727 | 0.510 | 1.000 | |||||||||

| RECRUIT | 0.388 | 0.652 | 0.722 | 0.480 | 0.788 | 1.000 | ||||||||

| IMPACT | 0.081 | 0.407 | 0.342 | 0.370 | 0.304 | 0.355 | 1.000 | |||||||

| SELF DETERMINATION | 0.109 | 0.393 | 0.356 | 0.382 | 0.358 | 0.415 | 0.707 | 1.000 | ||||||

| COMPETENCE | 0.064 | 0.190 | 0.171 | 0.230 | 0.142 | 0.186 | 0.575 | 0.531 | 1.000 | |||||

| MEANING | 0.170 | 0.338 | 0.266 | 0.340 | 0.227 | 0.286 | 0.624 | 0.491 | 0.555 | 1.000 | ||||

| NEGETIVE ARTEFACT | 0.142 | 0.225 | 0.189 | 0.174 | 0.186 | 0.206 | 0.078 | 0.099 | 0.156 | 0.237 | 1.000 | |||

| AFFECTIVE COMPONENT | 0.392 | 0.505 | 0.428 | 0.389 | 0.381 | 0.437 | 0.362 | 0.333 | 0.317 | 0.380 | 0.366 | 1.000 | ||

| PERFORM | 0.071 | 0.128 | 0.155 | 0.273 | 0.177 | 0.126 | 0.214 | 0.258 | 0.193 | 0.161 | −0.034 | 0.091 | 1.000 | |

| TRUST | 0.220 | 0.488 | 0.476 | 0.636 | 0.432 | 0.423 | 0.355 | 0.418 | 0.281 | 0.343 | 0.140 | 0.337 | 0.273 | 1.000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Khan, S.I.; Haque, A.; Bartram, T. Unleashing Employee Potential: A Mixed-Methods Study of High-Performance Work Systems in Bangladeshi Banks. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14636. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151914636

Khan SI, Haque A, Bartram T. Unleashing Employee Potential: A Mixed-Methods Study of High-Performance Work Systems in Bangladeshi Banks. Sustainability. 2023; 15(19):14636. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151914636

Chicago/Turabian StyleKhan, Sardana Islam, Amlan Haque, and Timothy Bartram. 2023. "Unleashing Employee Potential: A Mixed-Methods Study of High-Performance Work Systems in Bangladeshi Banks" Sustainability 15, no. 19: 14636. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151914636

APA StyleKhan, S. I., Haque, A., & Bartram, T. (2023). Unleashing Employee Potential: A Mixed-Methods Study of High-Performance Work Systems in Bangladeshi Banks. Sustainability, 15(19), 14636. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151914636