Perceptions of Urban Community Resilience: Beyond Disaster Recovery in the Face of Climate Change

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Review of the Literature

2.1. What Is Community Resilience?

2.2. Basic Resilience

2.3. Adaptive Resilience

2.4. Transformative Resilience

2.5. Systems, Resources, Assets, and Processes Considered as Important for Community Resilience

3. Methods

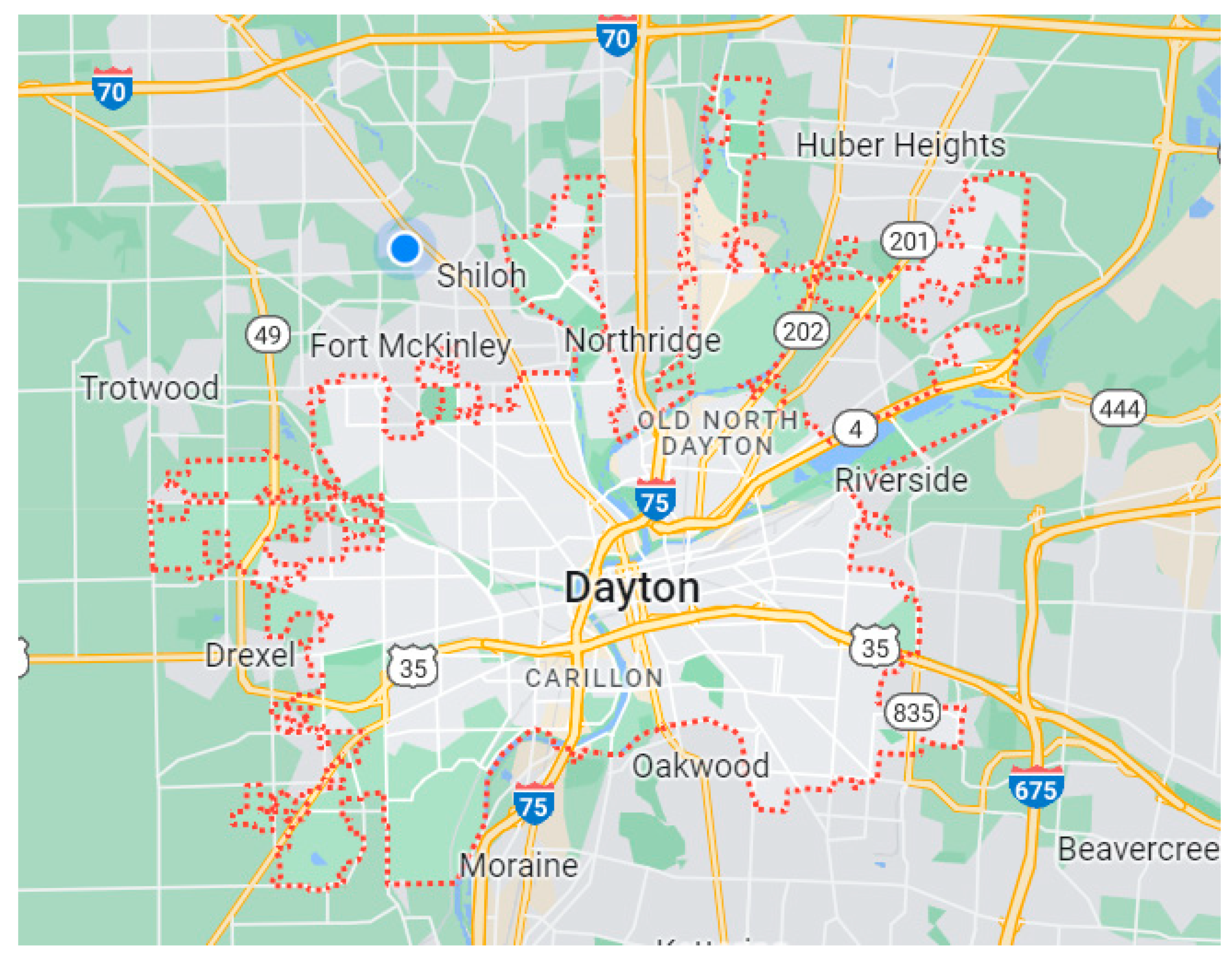

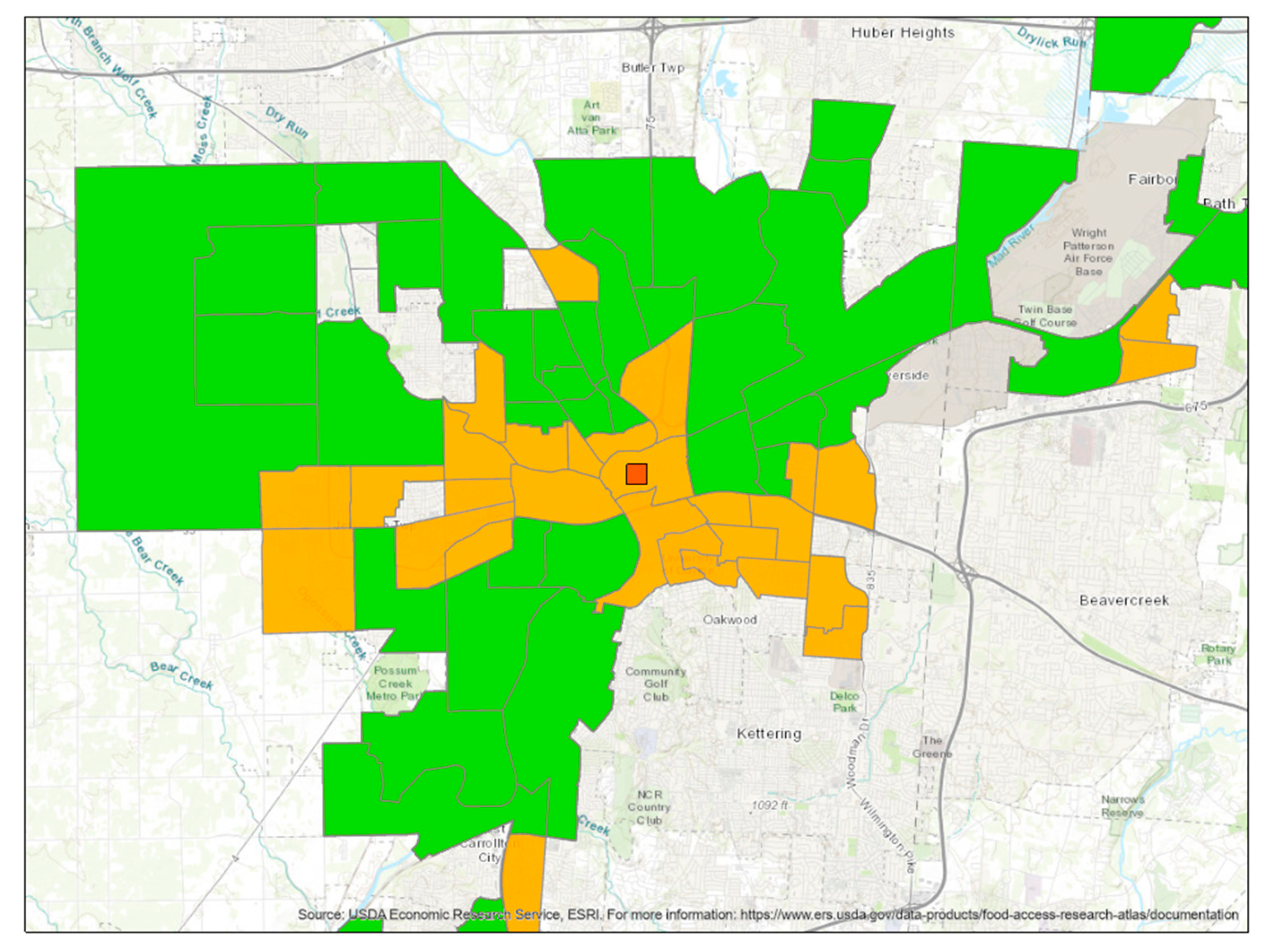

Description of the Research Site

4. Findings

4.1. Perceptions of Basic Resilience

“So I think, for me, resilience is really the ability to bounce back, when challenges come, how quickly can we, I think, recover. How quickly can we… From kind of the spiritual standpoint. So it’s not just on the surface level things are back to normal, but really healing and becoming whole again, in essence.”

“So if we’re talking about recovering people who are renters that maybe are thinking they’re ready to be permanent homeowners, that can swirl into an affordable housing conversation. And then attached to that, it could turn into, how are we building up our infrastructure that supports folks like that, that may not be living where they used to live, so now their commute to work is different, or maybe they’re not near the schools that they used to go to?”

“Okay, we don’t have any more demolitions, alright, so that’s one thing off the infrastructure list, but maybe we don’t have a grocery store in the neighborhood anymore because it got damaged. Well, is that still part of the disaster recovery effort, or is that part of now the obligation of the community and the businesses?”

“We know how to keep the power on, and we know how to get it back on…We’ve got really great processes in place to handle… We have processes in place to take calls from police and fire departments with issues that they see, you know, lines down in the middle of intersections, where people are at risk. We have dispatchers. And then the communications efforts that go into that, making sure the media knows what’s happening and customers know what’s happening and when they can expect power to be back on”

“I think that actually the chances are pretty good, we will have overlapping natural disasters. At a minimum, we won’t have recovered from the first one before the second one hits. At a maximum, we would have a wider spread debris field and disruption… And the emergency managers and staff have all grown up with a certain assumption about what this is gonna look like, and I think climate change just throws those assumptions to the wind, no pun intended.”

4.2. Perceptions of Adaptive Resilience

“it’s part preparedness, but also if we build back better, then we have better to start with, so we don’t have chinks in our armor that if something happens…So I guess just having better armor, and if we build back better, we will, and that can mean a lot of different things, including of course, our ability for our community to handle high water or the weather pattern changes that we’re seeing, and the ability to not only handle it, but be better afterwards.”

“If we can put them back, or put them back in different species or varieties because we can provide people with a huge advantage after the disaster…Maybe the folks in the neighborhood will feel safer because they have trees that provide coverage, or they have kids and families that wanna live there because of the infrastructure that it provides. You get a whole different sense of a neighborhood”

“So I also look at resiliency in terms of the grid as it exists today. The grid itself is well over 100 years old. Not all the parts and pieces are 100 years old, per se, but what we’ve built and put together. It’s probably one of the oldest working machines we have on the planet. So the other piece of resiliency to me is to make sure that we are performing the proper maintenance and replacement of our equipment to keep it as reliable as possible.”

“I would say is its ability to keep moving forward and ideally upward even through the trials and tribulations that life will put in its path. In Dayton the loss of the automotive industry, manufacturing industry that we had so relied on, it fed into so many other businesses, and there is a whole supply chain tied to that and a trickle-down effect even to the individual from businesses could be service-oriented businesses, that restaurant was in business and employed 20 people because workers from that plant came to this restaurant, that type of reality, the loss of a large portion of jobs where people had to go out and learn new skills or go back to school and be retrained.”

“Hope is a part of resilience, too, you have to have hope to know that you can get out of the darkness. I would define resilience as an ability to reveal hope and optimism in any situation so we can put our skill sets together to paint the bigger picture… I think that being resilient is being forward-thinking in how we teach our kids, in the opportunities that we give our kids, in breaking down race divides and class divides, and bringing people together. Again, Dayton is a resilient community. Dayton is a hopeful community. Dayton is a roll up your sleeves, get busy and do it kind of community.”

“No one has the money in this region. I would say you’d find the same thing in every urban area of this country to really meet the needs of maintaining a state of good repair. We made a commitment to fund what we knew would be capital improvements, about 250 million in capital improvements in about a five-year period, knowing if we didn’t get it done, there could be major failures within our systems. And like every old urban community, it’s old infrastructure, and it needs a huge investment.”

“It’s a really different story when you talk to the political leadership, for them to adopt resiliency plans or for them to adopt climate declarations, it’s hard for them to do that and not only here, it’s all over… And that makes sense that our political leaders are having more difficulty making these types of commitments or declarations because for whatever the reasoning is in our political climate today making these declarations to protect our environment or to reduce carbon emissions is a radical thing to do. So, it’s all like emergency planning, that’s what we have. Having the financial capacity and as well as people and political support and all that sort of stuff to do what sometimes is perceived as fluffy feel good extra let’s protect the environment, that’s gonna get pushed when things need to get cut.”

4.3. Perceptions of Transformative Resilience

“It’s like there’s so much that could be done around food to create a resilient local food economy and system, but I don’t see it happening anywhere. Everyone’s talking about food, but no one’s talking about creating a policy or system where you’re thinking about where it’s grown, what’s grown, how it gets to people who need it, and bringing people together to create that robust food economy. And I think the city could do things like talk about food access and say…these are ideas we have, after we’ve talked to community about, this is their issue. We’ll support them by developing vacant blighted properties into green spaces for farming. Or we’ll put money towards supporting people to learn how to become farmers as a workforce development tool, which creates a more resilient community”.

“You have to talk to your community, you have to build trust with your community to see what they need. They’ll tell you when they trust you. They’ll tell you what you need or what they need, and you’ll be able to provide that.”

“So the biggest example of that is the Gem City Market, which is a cooperatively owned grocery store. It’s owned by the community and the employees. It’s accountable to us because it’s owned by us, and there’s no third-party shareholders two states away making decisions about it. It meets a compelling community need because as you know, Dayton’s impacted by a food apartheid and it’s a grocery store in a neighborhood that hasn’t had grocery in like a decade.”

4.4. Important Resources, Systems, and Assets Perceived as Important for Community Resilience

“There’s an element to it as a neighborhood that involves knowing your neighbors. If you feel comfortable doing it, get your neighbor’s phone numbers in case you need to get in touch with them in an emergency. Because sometimes neighbors are the only ones that realize… Let’s say there’s a big storm and you’re out of town and a tree falls on your house. How are you gonna notify that neighbor if you don’t have a phone number for them? So, it’s real… It’s on a level that’s neighbor to neighbor.”

“If you have underlying problems in your community, then those kind of shocks will make them worse often. If you have underlying strengths, then those kind of shocks will not be as traumatic and they will be dealt with better… If people aren’t healthy because they don’t have good medical care and they don’t have access to healthy food, so anything that hits them, they’re weaker, and they’re more likely to suffer harsher impacts.”

“Well, yeah. I think the parts of the city that have low-income families and residents, and may not have the resources available to them to respond to impacts are particularly vulnerable. And not just to climate change, I think they’re vulnerable to a lot of other issues, health issues and just food and access to healthcare and things like that. I think those areas of the city, the low-income areas maybe are particularly vulnerable to any type of stressors that might come either short term or long-term.”

“There’s such a close correlation between redlining maps from the 1930s, the opportunity maps where there’s low opportunity, to the racial segregation patterns in the City of Dayton. And it’s like, they’re so interlinked. And it’s not that we’ve done anything wrong ourselves, we’re just living with these… these policies and decisions that people made 70, 80, 90 years ago. So in my mind, resiliency in my mind is thinking about… Has to include this equity piece, because if you’re not thinking about it through an equity lens, then you’re gonna miss out and you’re just gonna continue to perpetuate the injustices and the inequity that’s been going on for a century.”

“For example, racism, it certainly does on another level, and it certainly detracts from the resilience of those communities when they don’t have the investment in infrastructure, both environmental infrastructure and public open space that other communities have. I think that’s a key element in resilience in our community, that we really have to step up to these underserved communities”

5. Discussion

5.1. Similarities and differences in Community Resilience Perceptions and Policy Opportunities

5.2. Policies to Nurture Social Capital, Address Chronic Stressors, and Communication Infrastructure

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wilson, G.A. Community Resilience, Policy Corridors and the Policy Challenge. Land Use Policy 2013, 31, 298–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koliou, M.; van de Lindt, J.W.; McAllister, T.P.; Ellingwood, B.R.; Dillard, M.; Cutler, H. State of the Research in Community Resilience: Progress and Challenges. Sustain. Resilient Infrastruct. 2018, 5, 131–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wise, R.M.; Fazey, I.; Smith, M.S.; Park, S.; Eakin, H.C.; Van Garderen, E.; Campbell, B. Reconceptualizing Adaptation to Climate Change as Part of Pathways of Change and Response. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2014, 28, 325–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrios, R.E. “Here, I’m not at ease”: Anthropological Perspectives on Community Resilience. Disasters 2014, 38, 329–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutter, S.L.; Barnes, L.; Berry, M.; Burton, C.; Evans, E.; Tate, E.; Webb, J. A Place-based Model for Understanding Community Resilience to Natural Disasters. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2008, 18, 598–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, F.H.; Steven, S.P.; Pfefferbaum, B.; Wyche, K.F.; Pfefferbaum, R.L. Community Resilience as a Metaphor, Theory, set of Capacities, and Strategy for Disaster Readiness. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2008, 41, 127–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirmayer, L.J.; Sehdev, M.; Whitley, R.; Dandeneau, S.F.; Isaac, C. Community Resilience: Models, Metaphors and Measures. Int. J. Indig. Health 2009, 5, 62–117. [Google Scholar]

- Mochizuki, J.; Keating, A.; Liu, W.; Hochrainer-Stigler, S.; Mechler, R. An Overdue Alignment of Risk and Resilience? A Conceptual Contribution to Community Resilience. Disasters 2018, 42, 361–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spialek, M.L.; Czlapinski, H.M.; Houston, J.B. Disaster Communication Ecology and Community Resilience Perceptions Following the 2013 Central Illinois Tornadoes. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2016, 17, 154–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, A.D. Perceptions of Resilience Among Coastal Emergency Managers. Risk Hazards Crisis Public Policy 2016, 7, 4–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akerlof, K.; Moser, F.; Dindinger, J.; Rowan, K. Perceptions of Community Resilience: A Maryland Community Pilot Study; Center for Climate Change Communication, George Mason University: Fairfax, VA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Chondol, T.; Panda, A.K.; Gupta, A.K.; Agrawal, N.; Kaur, A. The Role of Perception of Local Government Officials on Climate Change and Resilient Development: A Case of Uttarakhand, India. Int. J. Disaster Resil. Built Environ. 2021, 12, 184–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Han, Z.; Han, Y.; Gong, Z. What do you Mean by Community Resilience? more Assets or Better Prepared? Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2022, 2, 706–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craft, L.L. Examining Community Resilience in the Disaster-Prone City of Conway, SC. J. Soc. Chang. 2020, 12, 151–165. [Google Scholar]

- Adekola, J.; Fischbacher-Smith, D.; Fischbacher-Smith, M. Inherent Complexities of a Multi-Stakeholder Approach to Building Community Resilience. Int. J. Disaster Risk Sci. 2020, 11, 32–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handmer, J.; Dovers, S. A Typology of Resilience: Rethinking Institutions for Sustainable Development. Ind. Environ. Crisis Q. 1996, 9, 482–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folke, C.; Carpenter, S.R.; Walker, B.; Scheffer, M.; Chapin, T.; Rockström, J. Resilience Thinking: Integrating Resilience, Adaptability and Transformability. Ecol. Soc. 2010, 15, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWethy, D.B.; Schoennagel, T.; Higuera, P.E.; Krawchuk, M.; Harvey, B.J.; Metcalf, E.C.; Schultz, C.; Miller, C.; Metcalf, A.L.; Buma, B.; et al. Rethinking Resilience to Wildfire. Nat. Sustain. 2019, 2, 797–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Harrison, M.T.; Yan, H.; Liu, D.L.; Meinke, H.; Hoogenboom, G.; Wang, B.; Peng, B.; Guan, K.; Jaegermeyr, J.; et al. Silver Lining to a Climate Crisis in Multiple Prospects for Alleviating Crop Waterlogging under Future Climates. Nat. Comm. 2023, 14, 765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masterson, J.H.; Peacock, W.G.; Van Zandt, S.S.; Grover, G.; Schwarz, L.F.; Cooper, J.T. Planning for Community Resilience: A Handbook for Reducing Vulnerability to Disasters, 3rd ed.; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Holling, C.S. Resilience and Stability of Ecological Systems. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1973, 4, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folke, C. Resilience (Republished). Ecol. Soc. 2016, 21, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh-Dilley, M.; Wolford, W. (Un)Defining Resilience: Subjective Understandings of “Resilience” from the Field. Resilience 2015, 3, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajić, T.; Vukolić, D.; Petrović, M.D.; Blešić, I.; Zrnić, M.; Cvijanović, D.; Sekulić, D.; Spasojević, A.; Obradović, M.; Obradović, A.; et al. Risks in the Role of Co-Creating the Future of Tourism in “Stigmatized” Destinations. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilbanks, T. Enhancing the Resilience of Communities to Natural and Other Hazards: What We Know and What We Can Do. Nat. Hazards Obs. 2008, 32, 10–11. [Google Scholar]

- Chandra, A.; Williams, M.; Plough, A.; Stayton, A.; Wells, K.B.; Horta, M.; Tang, J. Getting Actionable about Community Resilience: The Los Angeles County Community Disaster Resilience Project. Am. J. Public Health 2013, 103, 1181–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solomon, S.D.; Qin, D.; Manning, M.; Chen, Z.; Marquis, M.; Averyt, K.; Tignor, M.M.B.; Miller, H.L.M., Jr. (Eds.) IPCC Fourth Assessment Report; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Pelling, M. Adaptation to Climate Change: From Resilience to Transformation; Routledge: Oxford, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Asadzadeh, A.; Khavarian-Garmsir, A.R.; Sharifi, A.; Salehi, P.; Kötter, T. Transformative Resilience: An Overview of its Structure, Evolution, and Trends. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazey, I.; Carmen, E.; Chapin, F.S., III.; Ross, H.; Rao-Williams, J.; Lyon, C.; Connon, I.L.C.; Searle, B.A.; Knox, K. Community Resilience for a 1.5 °C World. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2018, 31, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kates, R.W.; Travis, W.R.; Wilbanks, T.J. Transformational Adaptation when Incremental Adaptations to Climate Change are Insufficient. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 7156–7161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedele, G.; Donatti, C.I.; Harvey, C.A.; Hannah, L.; Hole, D.G. Transformative Adaptation to Climate Change for Sustainable Social-Ecological Systems. Environ. Sci. Policy 2019, 101, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunderson, L. Ecological and Human Community Resilience in Response to Natural Disasters. Ecol. Soc. 2010, 15, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, J.; Schulz, K.; Vervoort, J.; Van Der Hel, S.; Sethi, M.; Barau, A. Exploring the Governance and Politics of Transformations Towards Sustainability. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2017, 24, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelling, M.; O’Brien, K.; Matyas, D. Adaptation and Transformation. Clim. Chang. 2015, 133, 113–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmqvist, T.; Andersson, E.; Frantzeskaki, N.; McPhearson, T.; Olsson, P.; Gaffney, O.; Takeuchi, K.; Folke, C. Sustainability and Resilience for Transformation in the Urban Century. Nat. Sustain. 2019, 2, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanner, T.M.; Lewis, D.; Wrathall, D.; Bronen, R.; Cradock-Henry, N.; Huq, S.; Lawless, C.; Nawrotzki, R.; Prasad, V.; Rahman, M.A.; et al. Livelihood Resilience in the Face of Climate Change. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2015, 5, 23–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrow, B.H. Community Resilience: A Social Justice Perspective; CARRI Research Report 4; Community and Regional Resilience Initiative: Gulfport, MS, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bergstrand, K.; Mayer, B.; Brumback, B.; Zhang, Y. Assessing the Relationship between Social Vulnerability and Community Resilience to Hazards. Soc. Indic. Res. 2015, 122, 391–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wachinger, G.; Renn, O.; Begg, C.; Kuhlicke, C. The Risk Perception Paradox—Implications for Governance and Communication of Natural Hazards. Risk Anal. 2013, 33, 1049–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapaport, C.; Hornik-Lurie, T.; Cohen, O.; Lahad, M.; Leykin, L.; Aharonson-Daniel, L. The Relationship Between Community type and Community Resilience. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2018, 31, 470–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfefferbaum, B.; Van Horn, R.L.; Pfefferbaum, R.L. A Conceptual Framework to Enhance Community Resilience using Social Capital. Clin. Soc. Work J. 2015, 45, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherrieb, K.; Norris, F.; Galea, S. Measuring Capacities for Community Resilience. Soc. Indic. Res. 2010, 99, 227–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldrich, D.P. The Importance of Social Capital in Building Community Resilience. In Rethinking Resilience Adaptation and Transformation in a Time of Change; Yan, W., Galloway, W., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2017; pp. 357–364. [Google Scholar]

- Houston, J.B. Community Resilience and Communication: Dynamic Interconnections Between and Among Individuals, Families and Organizations. J. Appl. Commun. Res. 2018, 46, 19–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flora, C.; Flora, J. Rural Communities, Legacy + Change, 4th ed.; Westview Press: Boulder, CO, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Stofferahn, C.W. Community Capitals and Disaster Recovery: Northwood ND Recovers from an EF 4 tornado. Community Dev. 2012, 43, 581–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, L.; Quinn, P.; Johnston, D.; Blake, D.; Campbell, E.; Brady, K. Recovery Capitals (RECAP): Applying a Community Capitals Framework to Disaster Recovery; Bushfire and Natural Hazards CRC: Melbourne, Australia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Biernacki, P.; Waldorf, D. Snowball Sampling: Problems and Techniques of Chain Referral Sampling. Sociol. Methods Res. 1981, 10, 141–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staley, S. Dayton, Ohio: The Rise, Fall, and Stagnation of a Former Industrial Juggernaut. 2008. Available online: http://www.newgeography.com/content/00153-dayton-ohio-the-rise-fall-and-stagnation-a-former-industrial-juggernaut (accessed on 8 August 2023).

- Frolik, C. Dayton Has One of the Highest Poverty Rates in the Nation. Dayton Daily News. 2020. Available online: https://www.daytondailynews.com/news/dayton-has-one-of-the-highest-poverty-rates-in-the-nation/Z62PSQG73RE4RDHASJ64YY5JDE (accessed on 10 August 2023).

- Great Lakes Adaptation Assessment (GLAA). The Potential Impacts of Climate Change on Dayton, Ohio. Available online: https://graham.umich.edu/glaac (accessed on 10 August 2023).

- Brown, K. Global Environmental Change I: A social turn for resilience? Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2014, 38, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fernando, F.N.; Maloney, M.; Tappel, L. Perceptions of Urban Community Resilience: Beyond Disaster Recovery in the Face of Climate Change. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14543. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151914543

Fernando FN, Maloney M, Tappel L. Perceptions of Urban Community Resilience: Beyond Disaster Recovery in the Face of Climate Change. Sustainability. 2023; 15(19):14543. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151914543

Chicago/Turabian StyleFernando, Felix N., Meg Maloney, and Lauren Tappel. 2023. "Perceptions of Urban Community Resilience: Beyond Disaster Recovery in the Face of Climate Change" Sustainability 15, no. 19: 14543. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151914543

APA StyleFernando, F. N., Maloney, M., & Tappel, L. (2023). Perceptions of Urban Community Resilience: Beyond Disaster Recovery in the Face of Climate Change. Sustainability, 15(19), 14543. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151914543