Valorizing Community Identity and Social Places to Implement Participatory Processes in San Giovanni a Teduccio (Naples, Italy)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Case Study: The Urban Area of San Giovanni a Teduccio

2.1. The Context

2.2. Methods and Procedures

2.3. Participants

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Disempowered Community

“The closed factory is closed for me; its condition does not affect me. A bit of an indolence. Broadly speaking, this can mean constant whining because you have a problem, and you keep it on you”(male, 40, referent of a cultural association)

“The community is not used to participating; it is a dormant community”(female, 37, referent of a local association)

“However, the park in Pazzigno [a district in San Giovanni a Teduccio] is completely abandoned, it has become a garbage dump. Closed! You could hire gardeners; you could hire guardians”(female, 58, citizen)

“For a while they tried to keep a listening center open. The first year there were more people who came… eventually, as time went on, no one came, since we were giving neither money nor concrete help… we just wanted to listen to them, help them, and accompany them in what we were doing by volunteering”(female, 57, citizen)

“That’s the biggest problem, it’s a place plagued by static, it’s not subject to change, maybe it gets worse it would be something new, but it stays there, still, motionless, it always pulls the same air, there are always the same winds, it doesn’t change”(male, 24, citizen)

“You would have to change all the people who live in San Giovanni a Teduccio. If you change the people, it becomes a good place to live. That is, it is not that they have gone to improve, they are just making it worse”(female, 68, citizen)

3.2. Threats and Weaknesses of San Giovanni

“Slowly, with the dismantling of all the industry that employed two thousand people… when these realities disappeared everything decayed, a complete decay that leads you to no livability and phenomena that we know of Camorra, of occupation of the territory of these organizations”(male, 76, citizen)

“I think there are high rates of crime, a lot of it. The operational side is right here, and I’m not just talking about San Giovanni, but also about Barra and Ponticelli [two neighborhoods adjacent]. It’s kind of ruining the area. The young people either do drugs, are camorrists, or shoot”(female, 58, citizen)

“There are small islands that are not always communicating. [...] As a neighborhood, San Giovanni is not aggregated; this is no longer a fact of will, it is rather because of the geographical arrangement of the neighborhood”(male, 76, citizen)

3.3. Community Relationships

“I feel quite involved because being a small neighborhood all the people know each other, and there is room for sharing. Going down the street, meeting people who know each other, talking—even for two minutes… I think for a person who has always lived here it is also quite easy in some ways to feel integrated”(female, 25, citizen)

“I see moving from San Giovanni as difficult precisely because there are these roots that tie you to the neighborhood, that condemn you in a way—kind of like a drug addiction, like any substance”(male, 24, citizen)

“There is an unhealthy air for me in this neighborhood, despite I was born here, and I feel close to certain people who live here, it is not an advisable place for me, but rather a place to flee…”(male, 24, citizen)

“Few people fall into the ranks of close ties, the rest… you can say I know everyone in San Giovanni, maybe the rotten part and the healthy one, and in these two parts are few people I care about, the rest are relationships characterized by convention and formality”(female, 68, citizen)

“Because it’s useless for us to do these things and then 100 m away the institutions create the economic port by lowering it from the top—because, again, it was lowered to us from the top, there was no interaction with the community, if it wasn’t for some community members who were a little more careful, we wouldn’t even have known about it”(male, 24, citizen)

“As Napoli ZETA, we are mainly addressing the ecodistrict, because it is a project that has already placed stakes dropped from above, without interaction and confrontation with the community”(female, 37, referent of a local association)

“However, there is a university of excellence here, there is the Apple Academy, they bring a flood of youths coming here, swarms of students. To go to work, my mom takes the 7 o’clock Vesuviana [a local public transport] and she sees all these youths coming to San Giovanni that she had never seen before”(female, 37, referent of a local association)

3.4. The Use of Local Places

“After dropping off the children, the mothers stop in the so-called square—but it is not a square. There is a little more space, a little wider sidewalk, but we call it a square [laughs] precisely because there is an absence of a square”(female, 57, citizen)

“Children still play in the street this is nice, this is good, because anyway you grow, you socialize, you still play with creativity…”(female, 57, citizen)

“You see it vibrant in the morning, then you see it a bit bustling in the afternoon because there is a passing of cars of people crossing the course. Then, it ends, there is nothing. You can see a little bit of people on the street in the morning, going to the grocery store, a few retirees at some bars in the afternoon, after that nobody goes out anymore”(male, 76, citizen)

“In the evening, on the other hand, it is frequented more by young adults who, however, have not so much of good intentions”(female, 58, citizen)

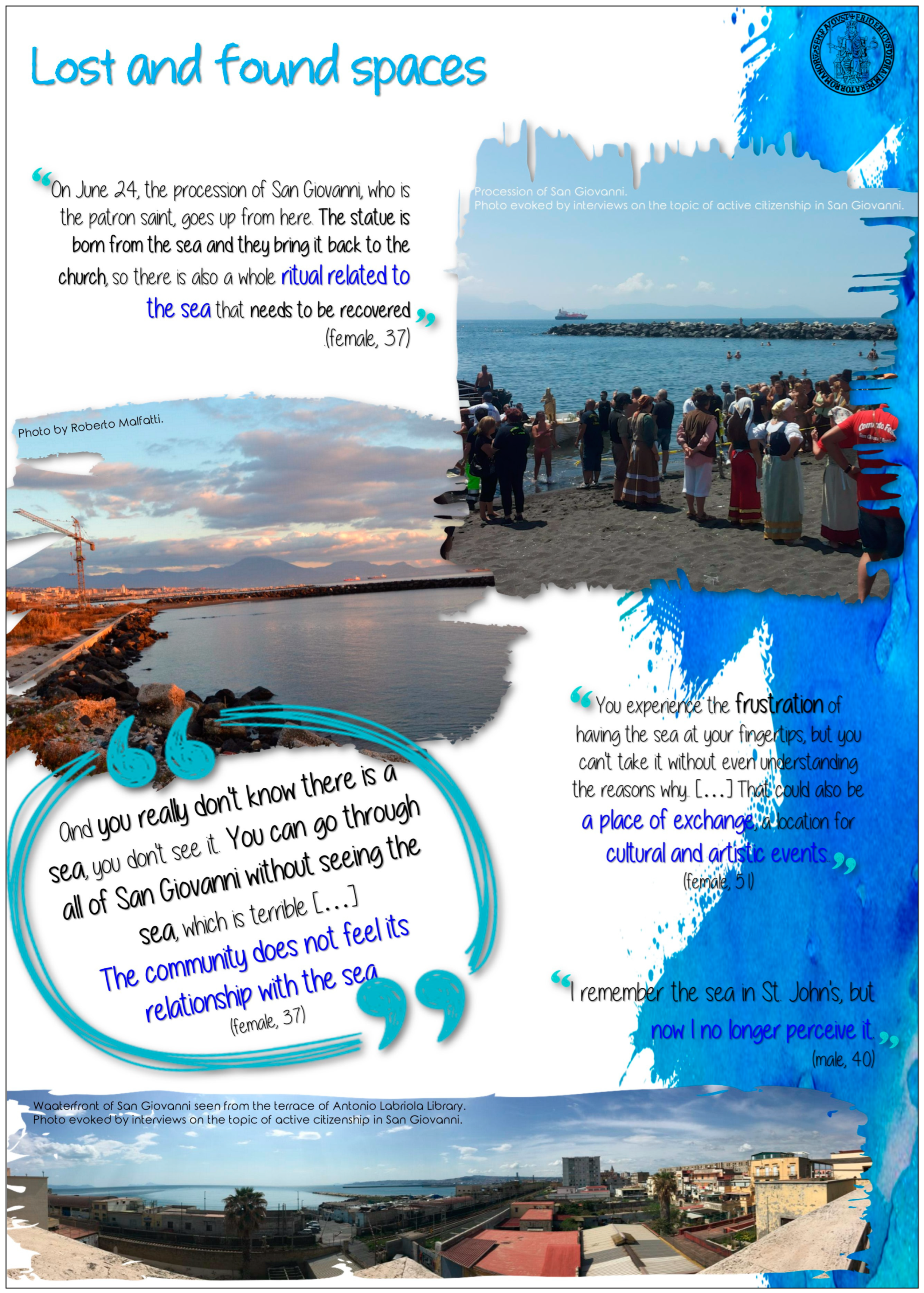

3.5. The Sea in San Giovanni

“They are used to smelling the stench of the refineries as the first thing when they arrive in San Giovanni; then, as the second thing, there is the Corso, and between this and the sea there are buildings, so you don’t see the sea, you have to look for it”(female, 37, referent of a local association)

“I remember the sea in San Giovanni, but now I don’t perceive it anymore. This is the big problem here, that you don’t even perceive it”(male, 40, referent of a cultural association)

“Last Summer we saw asbestos dumped on the waterfront and called those in charge, the municipal police offices, to remove it. So, the attention must always be high. However, it is still a lived-in waterfront, thanks in part to the community of fishermen who established there”(female, 37, referent of a local association)

“Some just don’t care and go to the beach anyway; they say, “This I can have, and I live it despite everything”. It’s kind of like when in the cabinet you have the jar of Nutella, but you can’t eat it; it would be better not to have it. You live the frustration of having something at your fingertips, but you can’t take it without even understanding the reasons for it. […] My great desire would be to resume the possibility of sea enjoyment. There is great potential there”(female, 50, referent of a cultural association)

“Areas should be created where the citizens can reappropriate the sea, e.g., in the former Corradini [a disused industrial building nearby the seaside] a sea museum, or a marine research center, could be made”(female, 37, referent of a local association)

3.6. Resilient Community

“I call them crazy but look at how much they believe… a strength is the stubbornness in not giving up. Even though they may break out into madness, it is a belief that is passed on, although there is no change and although people continue to die day after day, they continue to believe, which I would not do, it is something that I lack”(male, 24, citizen)

“We take the positive elements of the “bombs” and try to reconnect the social fabric moving from that”(female, 37, referent of a local association)

“At the feast of San Giovanni, with the church we organize the procession of San Giovanni a Mare, [...] and I have to tell the truth it’s a week of celebration for the neighborhood, they do the festival on the course, they do the theater in the street, the procession”(female, 58, citizen)

“If people see you doing, they are also willing to do. You show that it can be done”(female, 51, referent of a local association)

“And above all, in my opinion, highlighting what are the benefits that come from these kinds of actions and then trying to stimulate a strong motivation in making these spaces more aesthetically beautiful, more usable and so in some respects there is also a return of a better living condition”(female, 51, referent of a local association)

3.7. The Core Category: The Community as an Archipelago: Fragmentation of Resources

“To be a bit metaphorical, I can say that San Giovanni is like the mural that was made. It first was a bare wall; then with care, commitment, and will, it became a great work. In the sense that a lot more can be done for the area to really make it a great mural with collective efforts”(male, 62, citizen)

3.8. Photos of Significant Identity, Social, and Aggregative Places

- Troisi Park was pointed out as being an aggregative place for youths at present by three participants and as a potential meeting spot if regenerated by three other participants. It is a park characterized by the presence of a small lake, which was currently partly abandoned due to neglect;

- The mural depicting Maradona was pointed out as an aggregative place at present by one participant and as a potential meeting spot if differently valorized by another participant. It is a famous mural by the street artist Jorit, which was painted on the façade of one of the buildings in the so-called Bronx;

- The terrace of Antonio Labriola Library was pointed out being as an aggregative place at present by two participants and as a potential meeting spot if properly valorized by two more participants. It is said to offer one of the most beautiful views of the district, overlooking the Gulf of Naples and its waterfront;

- The waterfront was pointed out as being an aggregative place at present by three participants. They described it as particularly vibrant, especially during Summer, and as one of the favorite meeting spots for the inhabitants of San Giovanni a Teduccio;

- Local beaches were pointed out as aggregative places at present by one participant despite their current conditions. Indeed, they were reckoned as ideal places to organize concerts and parties in the evening. Furthermore, as a place particularly dear to the community of residents, the latter take advantage of it for swimming during the hottest hours of Summer despite the polluted state of the sea, which makes beaches aggregative places during daytime too in summertime;

- The Figli in Famiglia ONLUS was pointed out as an aggregative place at present by two participants. It is a meeting point for children and is considered a safe place for youths at risk, where after-school and recreational activities take place;

- The small squares of the Corso were pointed out as aggregative places at present by two participants despite their current conditions of partial degradation;

- The Pietrarsa Museum was pointed out as an aggregative place at present by one participant despite it being at the edge of the neighborhood;

- Pazzigno district was pointed out as a potential meeting spot if properly regenerated by three participants. Indeed, it hosts a multi-sports center, which had been a meeting place for the youths and whose great social potential is still recognized. Building on this, participants mentioned that it would deserve to be revitalized as a common for the whole community;

- The Town Hall square, in front of Antonio Labriola Library, was pointed out as a potential meeting spot if properly regenerated by two participants, despite the type of people who currently attended the square.

- Overall, what emerged from the photos suggested that the maritime and industrial identity was still felt as a critical part of community identity by local citizens, who showed ambivalent feelings towards the places characterizing such identity dimensions, that is, the sea, the waterfront, and the ex-industrial establishments. Indeed, on the one hand, they associated these elements to the main elements of their community identity and felt tied to them, wishing to be able to enjoy such spaces again, while on the other hand, they also felt that due to their current status, such places were no more able to hold their identity function and rather were run-down, neglected, and unlivable.

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gatti, F.; Procentese, F. Experiencing Urban Spaces and Social Meanings Through Social Media: Unravelling the Relationships between Instagram City-Related Use, Sense of Place, and Sense of Community. J. Environ. Psychol. 2021, 78, 101691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustafson, P. Meanings of place: Everyday experience and theoretical conceptualizations. J. Environ. Psychol. 2001, 21, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derrett, R. Making sense of how festivals demonstrate a community’s sense of place. Gather. Manag. 2003, 8, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, L.; Frank, L.D.; Giles-Corti, B. Sense of community and its relationship with walking and neighborhood design. Soc. Sci. Med. 2010, 70, 1381–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, G.; Ratiu, E.; Fleury-Bahi, G. Appropriation and interpersonal relationships: From dwelling to city through the neighborhood. Environ. Behav. 2002, 34, 122–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretty, G.H.; Chipuer, H.M.; Bramston, P. Sense of place amongst adolescents and adults in two rural Australian towns: The discriminating features of place attachment, sense of community and place dependence in relation to place identity. J. Environ. Psychol. 2003, 23, 273–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proshansky, H.M.; Fabian, A.K.; Kaminoff, R. Place-identity: Spatial world socialization of the self. J. Environ. Psychol. 1983, 3, 57–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnes, M.; Secchiaroli, G. Environmental Psychology: A Psycho-Social Introduction; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Convention on the Value of Cultural Heritage for Society (Faro Convention, 2005). Available online: https://www.coe.int/en/web/culture-and-heritage/faro-convention (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- Vickery, J. The Emergence of Culture-Led Regeneration: A Policy Concept and Its Discontents; Centre for Cultural Policy Studies (University of Warwick): Coventry, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Lorusso, S.; Cogo, G.M.; Natali, A. The protection and valorization of cultural and environmental heritage in the development process of the territory. Conserv. Sci. Cult. Herit. 2016, 16, 59–88. [Google Scholar]

- Boffi, M.; Rainisio, N.; Inghilleri, P. Nurturing Cultural Heritages and Place Attachment through Street Art—A Longitudinal Psycho-Social Analysis of a Neighborhood Renewal Process. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vícha, O. The Concept of the Right to Cultural Heritage within the Faro Convention. Int. Comp. Law Rev. 2014, 14, 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Landorf, C. A framework for sustainable heritage management: A study of UK industrial heritage sites. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2009, 15, 494–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canter, D. The Psychology of Place; Princeton Architectural Press: New York, NY, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Canter, D. Book Review of E. Relph, “Place and Placelessness”. Environ. Plan. 1978, 4, 118–120. [Google Scholar]

- Canter, D. Understanding, assessing and acting in places: Is an integrative framework possible? In Environmental Cognition and Action: An Integrated Approach; Garling, T., Evans, G., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Lewicka, M. Place attachment: How far have we come in the last 40 years? J. Environ. Psychol. 2011, 31, 207–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannarini, T.; Tartaglia, S.; Fedi, A.; Greganti, K. Image of neighborhood, self-image and sense of community. J. Environ. Psychol. 2006, 26, 202–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plas, J.M.; Lewis, S.E. Environmental factors and sense of community in a planned town. Am. J. Community Psychol. 1996, 24, 109–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarason, S.B. The Psychological Sense of Community: Prospects for a Community Psychology; Jossey-Bass: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Vick, J.W.; Perkins, D.D. Building community: Comparing resident satisfaction, sense of community, and neighboring in a New Urban and a suburban neighborhood. In Back to the Future: New Urbanism and the Rise of Neotraditionalism in Urban Planning; Besel, K., Andreescu, V., Eds.; University Press of America: Lanham, MD, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Masterson, V.A.; Stedman, R.C.; Enqvist, J.; Tengö, M.; Giusti, M.; Wahl, D.; Svedin, U. The contribution of sense of place to social-ecological systems research: A review and research agenda. Ecol. Soc. 2017, 22, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymond, C.M.; Kyttä, M.; Stedman, R. Sense of place, fast and slow: The potential contributions of affordance theory to sense of place. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.R. Making sense of ‘place’: Reflections on pluralism and positionality in place research. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2014, 131, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.; Roberts, S.; Pagliaro, S.; Csikszentmihalyi, M.; Bonaiuto, M. Optimal experience and optimal identity: A multinational study of the associations between flow and social identity. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twigger-Ross, C.; Bonaiuto, M.; Breakwell, G. Identity theories and environmental psychology. In Psychological Theories for Environmental Issues; Bonnes, M., Lee, T., Bonaiuto, M., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; pp. 203–233. [Google Scholar]

- Cresswell, T. Place: A Short Introduction; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hull, R.B., IV; Lam, M.; Vigo, G. Place identity: Symbols of self in the urban fabric. Land. Urban Plan. 1994, 28, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puddifoot, J.E. Exploring “personal” and “shared” sense of community identity in Durham city, England. J. Community Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 31, 87–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention; UNESCO World Heritage Centre: Paris, France, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Arcidiacono, C.; Clemente, M.; Giovene Di Girasole, E.; Procentese, F. Identità marittima e dimensione collaborativa per la rigenerazione e valorizzazione della costa metropolitana di Napoli. Urban. Inf. 2015, 263, 27–30. [Google Scholar]

- Arcidiacono, C. (Ed.) Psicologia di Comunità per le Città. Rigenerazione Urbana a Porta Capuana; Liguori: Napoli, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Arcidiacono, C.; Procentese, F. Distinctiveness and sense of community in the historical center of Naples: A piece of participatory action research. J. Community Psychol. 2005, 33, 631–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Burris, M.A. Photovoice: Concept, methodology, and use for participatory needs assessment. Health Educ. Behav. 1997, 24, 369–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster-Fishman, P.; Nowell, B.; Deacon, Z.; Nievar, M.A.; McCann, P. Using methods that matter: The impact of reflection, dialogue, and voice. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2005, 36, 275–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, A.L.; Corbin, J. Basics of Qualitative Research, 1st ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz, K. Grounded theory: Objectivist and constructivist methods. Handb. Qual. Res. 2000, 2, 509–535. [Google Scholar]

- Doolittle, A.; Faul, A.C. Civic engagement scale: A validation study. Sage Open 2013, 3, 2158244013495542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyman, J.B. Exploring social capital and civic engagement to create a framework for community building. Appl. Dev. Sci. 2002, 6, 196–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodsky, A. Resilient single mothers in risky neighborhoods: Negative psychological sense of community. J. Community Psychol. 1996, 16, 771–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannarini, T.; Rochira, A.; Talo, C. Negative psychological sense of community: Development of a measure and theoretical implications. J. Community Psychol. 2014, 42, 673–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattei, U. Beni Comuni, Un Manifesto; Laterza: Bari, Italy, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E. Governing the Commons. The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Rifkin, J. La società a Costo Marginale Zero; Mondadori: Milano, Italy, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Mantovani, G. (Ed.) Manuale di Psicologia Sociale; Giunti Editore: Firenze, Italy, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Seligman, M.E. Learned helplessness. Annu. Rev. Med. 1972, 23, 407–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Procentese, F.; Gargiulo, A.; Gatti, F. Local Groups’ Actions to Develop a Sense of Responsible Togetherness. Psicol. Di Comunità 2020, 1/2020, 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewin, K. Field Theory in Social Science: Selected Theoretical Papers; Harpers: New York, NY, USA, 1951. [Google Scholar]

- March, G.; Olsen, J.P. Rediscovering Institutions: The Organizational Basis of Politics; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Wiesenfeld, E. The concept of “we”: A community social psychology myth? J. Community Psychol. 1996, 24, 337–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, P.R. Community heritage work in Africa: Village-based preservation and development. Conserv. Sci. Cult. Herit. 2014, 14, 133–150. [Google Scholar]

- Verdini, G.; Frassoldati, F.; Nolf, C. Reframing China’s heritage conservation discourse. Learning by testing civic engagement tools in a historic rural village. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2017, 23, 317–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srijuntrapun, P.; Fisher, D.; Rennie, H.G. Assessing the sustainability of tourism-related livelihoods in an urban World Heritage Site. J. Herit. Tour. 2017, 9, 395–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Procentese, F.; Gatti, F. Sense of Responsible Togetherness, Sense of Community, and Civic Engagement Behaviors: Disentangling an Active and Engaged Citizenship. J. Community Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2022, 32, 186–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Procentese, F.; De Carlo, F.; Gatti, F. Civic Engagement within the Local Community and Sense of Responsible Togetherness. TPM—Test. Psychom. Methodol. Appl. Psychol. 2019, 26, 513–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatti, F.; Procentese, F. Open Neighborhoods, Sense Of Community, And Instagram Use: Disentangling Modern Local Community Experience Through A Multilevel Path Analysis With A Multiple Informant Approach. TPM—Test. Psychom. Methodol. Appl. Psychol. 2020, 27, 313–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guba, E.G. Criteria for assessing the trustworthiness of naturalistic inquiries. ECTJ 1981, 29, 75–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- What Makes a Successful Place? Available online: http://www.pps.org/topics/gps/gr_place_feat (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- Brown, B.B.; Perkins, D.D.; Brown, G. Incivilities, place attachment and crime: Block and individual effects. J. Environ. Psychol. 2004, 24, 359–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewicka, M. Ways to make people active: The role of place attachment, cultural capital, and neighborhood ties. J. Environ. Psychol. 2005, 25, 381–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özkan, D.G.; Yilmaz, S. The effects of spatial and social attributes of place on place attachment: A case study on Trabzon urban squares. Archnet-IJAR Int. J. Archit. Res. 2019, 13, 133–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Félonneau, M.L. Love and loathing of the city: Urbanophilia and urbanophobia, topological identity and perceived incivilities. J. Environ. Psychol. 2004, 24, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornara, F.; Ariccio, S.; Rioux, L.; Moffat, E.; Mariette, J.; Bonnes, M.; Bonaiuto, M. Test of PREQIs’ factorial structure and reliability in France and of a Neighbourhood Attachment prediction model: A study on a French sample in Paris. Prat. Psychol. 2018, 24, 131–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorgensen, B.S.; Stedman, R.C. Sense of place as an attitude: Lakeshore owners’ attitudes toward their properties. J. Environ. Psychol. 2001, 21, 233–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rollero, C.; De Piccoli, N. Place attachment, identification and environment perception: An empirical study. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 198–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brehm, J.M.; Eisenhauer, B.W.; Stedman, R.C. Environmental concern: Examining the role of place meaning and place attachment. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2013, 26, 522–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacquet, J.B.; Stedman, R.C. Perceived impacts from wind farm and natural gas development in northern Pennsylvania. Rural Sociol. 2013, 78, 450–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Macro-Categories | Categories |

|---|---|

| 1. Disempowered community | (a) Nostalgia and resignation |

| (b) Lack of values and awareness about the current circumstances | |

| (c) Low rates of participation | |

| 2. Threats and weaknesses of San Giovanni | (a) Presence of organized crime activities |

| (b) Abandoned community spaces | |

| 3. Community relationships | (a) Relationships within the community |

| (b) Relationships with the outgroup | |

| (c) The role of local associations | |

| (d) Relationships with Institutional referents | |

| 4. The use of local places | (a) Different uses depending on the time of the day |

| (b) Social and aggregative functions | |

| 5. The sea in San Giovanni | (a) The invisible sea |

| (b) The sea as a common good | |

| (c) The sea as an identity element | |

| 6. Resilient community | (a) Active citizenship |

| (b) Flywheels for participatory processes |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Procentese, F.; Gatti, F. Valorizing Community Identity and Social Places to Implement Participatory Processes in San Giovanni a Teduccio (Naples, Italy). Sustainability 2023, 15, 14216. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151914216

Procentese F, Gatti F. Valorizing Community Identity and Social Places to Implement Participatory Processes in San Giovanni a Teduccio (Naples, Italy). Sustainability. 2023; 15(19):14216. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151914216

Chicago/Turabian StyleProcentese, Fortuna, and Flora Gatti. 2023. "Valorizing Community Identity and Social Places to Implement Participatory Processes in San Giovanni a Teduccio (Naples, Italy)" Sustainability 15, no. 19: 14216. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151914216

APA StyleProcentese, F., & Gatti, F. (2023). Valorizing Community Identity and Social Places to Implement Participatory Processes in San Giovanni a Teduccio (Naples, Italy). Sustainability, 15(19), 14216. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151914216