Navigating Emergencies: A Theoretical Model of Civic Engagement and Wellbeing during Emergencies

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Basis

2.1. Civic Engagement: Definition and Meaning

2.2. Civic Engagement in Turbulent Times

2.3. Governance Efficacy and Emergency-Oriented Civic Engagement

2.4. The Differences between Emergencies, Crises, and Disasters and Study Operationalization

3. Materials and Development of Propositions

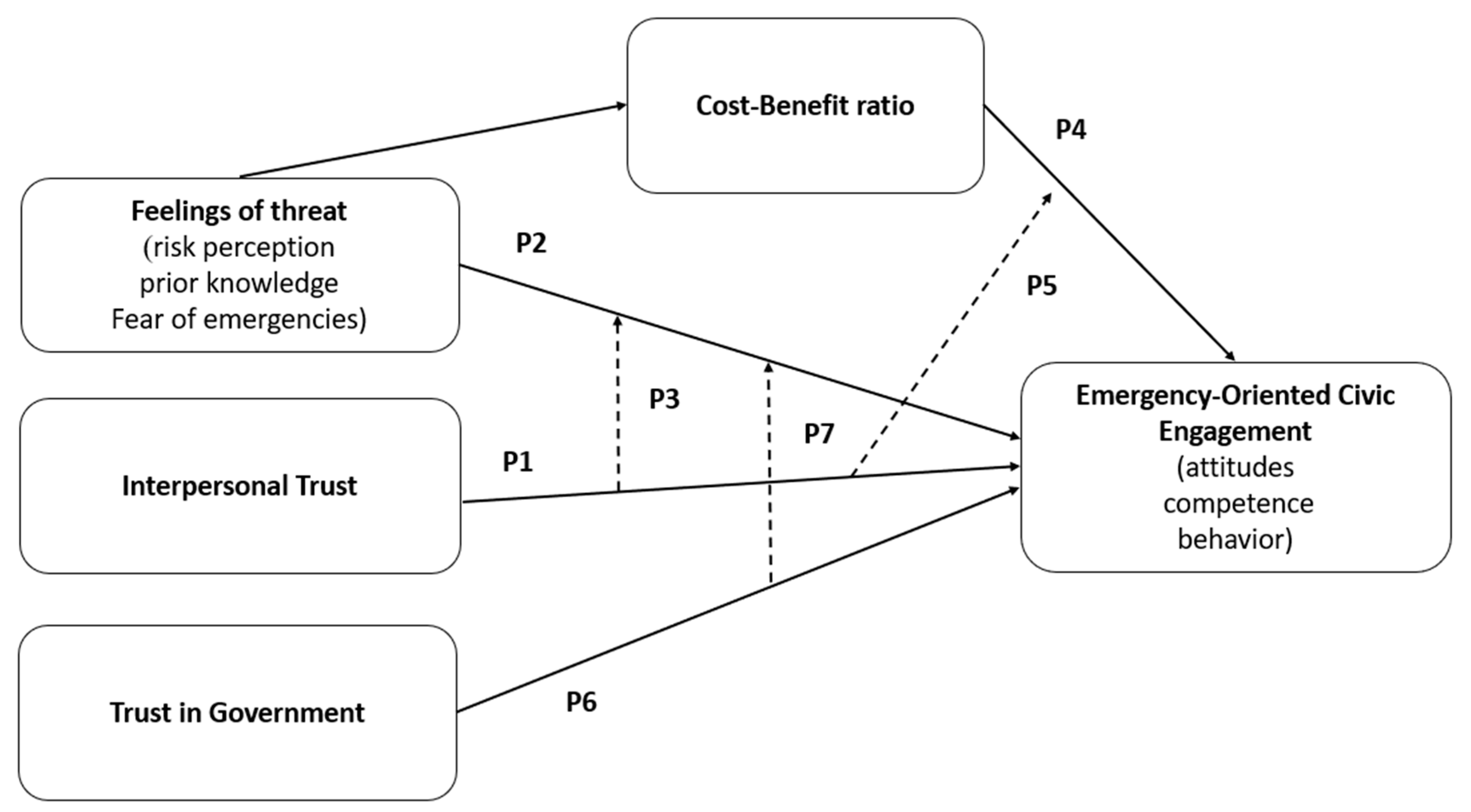

3.1. EOCE: The Model and Its Rationale

3.2. The Direct Effect of Interpersonal Trust on EOCE

3.3. The Relationship between Feelings of Threat and EOCE

3.4. Cost–Benefit Ratio as a Mediator between Feelings of Threat and EOCE

3.5. The Direct and Moderating Effect of Trust in Government on EOCE

4. Discussion, Summary, and Road Ahead

Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- French, P.E. Enhancing the legitimacy of local government pandemic influenza planning through transparency and public engagement. Public Adm. Rev. 2011, 71, 253–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, K.A.; Lane, A.B. Building relational capital: The contribution of episodic and relational community engagement. Public Relat. Rev. 2018, 44, 633–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, W.; Fang, Z.; Hou, G.; Han, M.; Xu, X.; Dong, J.; Zheng, J. The psychological impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on college students in China. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 287, 112934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlsen, H.B.; Toubøl, J.; Brincker, B. On solidarity and volunteering during the COVID-19 crisis in Denmark: The impact of social networks and social media groups on the distribution of support. Eur. Soc. 2021, 23, S122–S140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grasso, M.; Lahusen, C. Solidarity in Europe. A comparative account of citizens’ attitudes and practices. Citizens’ Solidar. Eur. 2020, 29, 29–54. [Google Scholar]

- Col, J.M. Managing disasters: The role of local government. Public Adm. Rev. 2007, 67, 114–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borbáth, E.; Hunger, S.; Hutter, S.; Oana, I.E. Civic and Political Engagement during the Multifaceted COVID-19 Crisis. Swiss Political Sci. Rev. 2021, 27, 311–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoker, G. Public value management: A new narrative for networked governance? Am. Rev. Public Adm. 2006, 36, 41–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, T.L.; Bryer, T.A.; Meek, J.W. Citizen-centered collaborative public management. Public Adm. Rev. 2006, 66, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Checkoway, B.; Aldana, A. Four forms of youth civic engagement for diverse democracy. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2013, 35, 1894–1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega-Tinoco, A.; Gil-Lacruz, A.I.; Gil-Lacruz, M. Does Civic Participation Promote Active Aging in Europe? VOLUNTAS Int. J. Volunt. Nonprofit Organ. 2021, 33, 599–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feitelson, E.; Plaut, P.; Salzberger, E.; Shmueli, D.; Altshuler, A.; Ben-Gal, M.; Zaychik, D. The effects of COVID-19 on wellbeing: Evidence from Israel. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pancer, S.M. The Psychology of Citizenship and Civic Engagement; Oxford University Press: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bovaird, T. Beyond engagement and participation: User and community coproduction of public services. Public Adm. Rev. 2007, 67, 846–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Cho, M. Examining the role of sense of community: Linking local government public relationships and community-building. Public Relat. Rev. 2019, 45, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicognani, E.; Mazzoni, D.; Albanesi, C.; Zani, B. Sense of community and empowerment among young people: Understanding pathways from civic participation to social well-being. VOLUNTAS Int. J. Volunt. Nonprofit Organ. 2015, 26, 24–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, R.D. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community; Simon & Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, D.V. Civic engagement, interpersonal trust, and television use: An individual-level assessment of social capital. Political Psychol. 1998, 19, 469–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopp, T.; Ferrucci, P. A spherical rendering of deviant information resilience. J. Mass Commun. Q. 2020, 97, 492–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. A behavioral approach to the rational choice theory of collective action: Presidential address, American Political Science Association, 1997. Am. Political Sci. Rev. 1998, 92, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michels, A. Innovations in democratic governance: How does citizen participation contribute to a better democracy? Int. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2011, 77, 275–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitag, M. Bowling the state back in: Political institutions and the creation of social capital. Eur. J. Political Res. 2006, 45, 123–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaler, T.; Levin-Keitel, M. Multi-level stakeholder engagement in flood risk management—A question of roles and power: Lessons from England. Environ. Sci. Policy 2016, 55, 292–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, S.; Galambos, N.L.; Johnson, M.D.; Krahn, H.J. Happiness is the way: Paths to civic engagement between young adulthood and midlife. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2018, 42, 425–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborne, S.P. The New Public Governance. Public Manag. Rev. 2006, 8, 377–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekkers, V.; Tummers, L. Citizen participation in emergency management: A review of the literature. Int. J. Public Adm. 2018, 41, 65–76. [Google Scholar]

- Denny, E. Crisis, Resilience, and Civic Engagement: Pandemic-Era Census Completion. Perspect. Politics 2021, 20, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morello-Frosch, R.; Brown, P.; Lyson, M.; Cohen, A.; Krupa, K. Community voice, vision, and resilience in post-Hurricane Katrina recovery. Environ. Justice 2011, 4, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, D.F.; Chang, T.N.; Chen, C.C. Exploring the Effect of College Students’ Civic Engagement on Transferable Capabilities during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitálišová, K.; Dvořák, J. Differences and Similarities in Local Participative Governance in Slovakia and Lithuania. In Participatory and Digital Democracy at the Local Level. Contributions to Political Science; Rouet, G., Côme, T., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Quarantelli, E.L. Catastrophes are different from disasters: Some implications for crisis planning and managing drawn from Katrina. In Understanding Katrina: Perspectives from the Social Science; American Sociological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Boin, A.; Hart, P.T.; Kuipers, S. The crisis approach. In Handbook of Disaster Research; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 23–38. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, D. Towards the development of a standard in emergency planning. Disaster Prev. Manag. Int. J. 2005, 14, 158–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Q.; Sundararaj, V.; Mr, R. Analyzing the factors affecting the attitude of the public toward lockdown, institutional trust, and civic engagement activities. J. Community Psychol. 2022, 50, 806–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waeterloos, C.; De Meulenaere, J.; Walrave, M.; Ponnet, K. Tackling COVID-19 from below: Civic participation among online neighborhood network users during the COVID-19 pandemic. Online Inf. Rev. 2021, 45, 777–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrew, S.A.; Jung, K.; Li, X. Grass-root organizations, intergovernmental collaboration, and emergency preparedness: An institutional collective action approach. Local Gov. Stud. 2015, 41, 673–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.A. Coronavirus Anxiety Scale: A brief mental health screener for COVID-19 related anxiety. Death Stud. 2020, 44, 393–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Yang, L.; Zhang, C.; Xiang, Y.T.; Liu, Z.; Hu, S.; Zhang, B. Online mental health services in China during the COVID-19 outbreak. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, e17–e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janse, G.; Konijnendijk, C.C. Communication between science, policy, and citizens in public participation in urban forestry—Experiences from the Neighbourwoods project. Urban For. Urban Green. 2007, 6, 23–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doolittle, A.; Faul, A.C. Civic engagement scale: A validation study. Sage Open 2013, 3, 2158244013495542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Zomeren, M.; Postmes, T.; Spears, R. Toward an integrative social identity model of collective action: A quantitative research synthesis of three socio-psychological perspectives. Psychol. Bull. 2008, 134, 504–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zomeren, M.; Saguy, T.; Schellhaas, F.M. Believing in “making a difference” to collective efforts: Participative efficacy beliefs as a unique predictor of collective action. Group Process. Intergroup Relat. 2013, 16, 618–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischhoff, B.; Slovic, P.; Lichtenstein, S.; Read, S.; Combs, B. How safe is safe enough? A psychometric study of attitudes towards technological risks and benefits. Policy Sci. 1978, 9, 127–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slovic, P. The Feeling of Risk: New Perspectives on Risk Perception; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Boin, A.; Bynander, F. Explaining success and failure in crisis coordination. Geogr. Ann. Ser. A Phys. Geogr. 2015, 97, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, K.; Song, M.; Park, H.J. The dynamics of an interorganizational emergency management network: Interdependent and independent risk hypotheses. Public Adm. Rev. 2019, 79, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nannestad, P. What have we learned about generalized trust, if anything? Annu. Rev. Political Sci. 2008, 11, 413–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.M.L.; Jensen, O. The paradox of trust: Perceived risk and public compliance during the COVID-19 pandemic in Singapore. J. Risk Res. 2020, 23, 1021–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Holzer, M. The performance-trust link: Implications for performance measurement. Public Adm. Rev. 2006, 66, 114–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Offe, C. How can we trust our fellow citizens. Democr. Trust 1999, 52, 42–87. [Google Scholar]

- Suh, H.; Reynolds-Stenson, H. A contingent effect of trust? Interpersonal trust and social movement participation in a political context. Soc. Sci. Q 2018, 99, 1484–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuyama, F. Trust: The Social Virtues and the Creation of Prosperity; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Uslaner, E.M. The Moral Foundations of Trust; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Miranti, R.; Evans, M. Trust, Sense of Community, and Civic Engagement: Lessons from Australia. J. Community Psychol. 2019, 47, 254–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, M.; Rochon, T.R. Interpersonal Trust and the Magnitude of Protest: A Micro and Macro Level Approach. Comp. Political Stud. 2004, 37, 435–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, P.R.; Steenbergen, M.R. All Against All: How Beliefs About Human Nature Shape Foreign Policy Opinions. Political Psychol. 2002, 23, 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fell, L. Trust and COVID-19: Implications for Interpersonal, Workplace, Institutional, and Information-Based Trust. Digit. Gov. Res. Pract. 2020, 2, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casey, B.H. COVID-19: Did Higher Trust Societies Fare Better? Discov. Soc. Sci. Health 2023, 3, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, J.K.; Record, M. Local Capitalism and Civic Engagement: The Potential of Locally Facing Firms. Public Adm. Rev. 2017, 77, 875–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, E.A.; Renn, O.; McCright, A.M. The Risk Society Revisited: Social Theory and Governance; Temple University Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Chong, D. Collective Action and the Civil Rights Movement; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Olson, M. The Logic of Collective Action: Public Goods and the Theory of Groups; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Bubeck, P.; Botzen, W.J.W.; Aerts, J.C. A Review of Risk Perceptions and Other Factors that Influence Flood Mitigation Behavior. Risk Anal. Int. J. 2012, 32, 1481–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bickerstaff, K. Risk Perception Research: Socio-cultural Perspectives on the Public Experience of Air Pollution. Environ. Int. 2004, 30, 827–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer, R.A.; Klein, W.M.; Avishai, A.; Jones, K.; Villegas, M.; Sheeran, P. When Does Risk Perception Predict Protection Motivation for Health Threats? A Person-by-Situation Analysis. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0191994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grothmann, T.; Reusswig, F. People at Risk of Flooding: Why Some Residents Take Precautionary Action While Others Do Not. Nat. Hazards 2006, 38, 101–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wise, T.; Zbozinek, T.D.; Michelini, G.; Hagan, C.C.; Mobbs, D. Changes in Risk Perception and Self-reported Protective Behaviour During the First Week of the COVID-19 Pandemic in the United States. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2020, 7, 200742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, K.; Han, Z.; Wang, D. Resilience of an Earthquake-stricken Rural Community in Southwest China: Correlation with Disaster Risk Reduction Efforts. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Lin, L.; Xuan, Z.; Xu, J.; Wan, Y.; Zhou, X. Risk Communication on Behavioral Responses During COVID-19 Among the General Population in China: A Rapid National Study. J. Infect. 2020, 81, 911–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanciano, T.; Graziano, G.; Curci, A.; Costadura, S.; Monaco, A. Risk Perceptions and Psychological Effects during the Italian COVID-19 Emergency. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 580053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuwirth, K.; Dunwoody, S.; Griffin, R.J. Protection Motivation and Risk Communication. Risk Anal. 2000, 20, 721–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, S.; Nicholson-Cole, S. “Fear Won’t Do It” Promoting Positive Engagement with Climate Change Through Visual and Iconic Representations. Sci. Commun. 2009, 30, 355–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loewenstein, G.F.; Weber, E.U.; Hsee, C.K.; Welch, N. Risk as Feelings. Psychol. Bull. 2001, 127, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, W.E.; Martin, I.M.; Kent, B. The Role of Risk Perceptions in the Risk Mitigation Process: The Case of Wildfire in High-Risk Communities. J. Environ. Manag. 2009, 91, 489–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Earle, T.C. Trust in Risk Management: A Model-Based Review of Empirical Research. Risk Anal. Int. J. 2010, 30, 541–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mannarini, T.; Fedi, A.; Trippetti, S. Public Involvement: How to Encourage Citizen Participation. J. Community Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 20, 262–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downs, A. An Economic Theory of Democracy; Harper and Row: New York, NY, USA, 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Homans, G.C. Social Behavior as Exchange. Am. J. Sociol. 1958, 63, 597–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazzi, S.; Fiszbein, M.; Gebresilasse, M. “Rugged Individualism” and Collective (In)Action During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Public Econ. 2021, 195, 104357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollock, P. Social Dilemmas: The Anatomy of Cooperation. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1998, 24, 183–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.; Long, Q.; Huang, G.; Huang, L.; Luo, S. Different Roles of Interpersonal Trust and Institutional Trust in COVID-19 Pandemic Control. Soc. Sci. Med. 2022, 293, 114677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seebauer, S.; Babcicky, P. Trust and the Communication of Flood Risks: Comparing the Roles of Local Governments, Volunteers in Emergency Services, and Neighbours. J. Flood Risk Manag. 2018, 11, 305–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Civinskas, R.; Dvorak, J.; Šumskas, G. Beyond the front-line: The coping strategies and discretion of Lithuanian street-level bureaucracy during COVID-19. Corvinus J. Sociol. Soc. Policy 2021, 12, 3–28. [Google Scholar]

- Lipsky, M. Street-Level Bureaucracy: Dilemmas of the Individual in Public Service; Russell Sage Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 14–15. [Google Scholar]

- Verger, P.; Bocquier, A.; Vergélys, C.; Ward, J.; Peretti-Watel, P. Flu Vaccination Among Patients with Diabetes: Motives, Perceptions, Trust, and Risk Culture—A Qualitative Survey. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vigoda-Gadot, E. Public Administration: An Interdisciplinary Critical Analysis; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Mizrahi, S.; Vigoda-Gadot, E.; Cohen, N. How Well Do They Manage a Crisis? The Government’s Effectiveness during the Covid-19 Pandemic. Public Adm. Rev. 2021, 81, 1120–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hardin, R. The Street-Level Epistemology of Trust. Politics Soc. 1993, 21, 505–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-Determination Theory: Basic Psychological Needs in Motivation, Development, and Wellness; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Poortinga, W.; Pidgeon, N.F. Exploring the Dimensionality of Trust in Risk Regulation. Risk Anal. Int. J. 2003, 23, 961–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cologna, V.; Siegrist, M. The Role of Trust for Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation Behaviour: A Meta-Analysis. J. Environ. Psychol. 2020, 69, 101428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Gunsteren, H. A Theory of Citizenship: Organizing Plurality in Contemporary Democracies; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lourenço, R.P.; Costa, J.P. Incorporating Citizens’ Views in Local Policy Decision-Making Processes. Decis. Support Syst. 2007, 43, 1499–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mishor, E.; Vigoda-Gadot, E.; Mizrahi, S. Exploring civic engagement dynamics during emergencies: An empirical study into key drivers. Policy Politics, 2023; 1–23, early review. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfman, N.C.; Cisternas, P.C.; López-Vázquez, E.; Cifuentes, L.A. Trust and Risk Perception of Natural Hazards: Implications for Risk Preparedness in Chile. Nat. Hazards 2016, 81, 307–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Blitstein-Mishor, E.; Vigoda-Gadot, E.; Mizrahi, S. Navigating Emergencies: A Theoretical Model of Civic Engagement and Wellbeing during Emergencies. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14118. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151914118

Blitstein-Mishor E, Vigoda-Gadot E, Mizrahi S. Navigating Emergencies: A Theoretical Model of Civic Engagement and Wellbeing during Emergencies. Sustainability. 2023; 15(19):14118. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151914118

Chicago/Turabian StyleBlitstein-Mishor, Efrat, Eran Vigoda-Gadot, and Shlomo Mizrahi. 2023. "Navigating Emergencies: A Theoretical Model of Civic Engagement and Wellbeing during Emergencies" Sustainability 15, no. 19: 14118. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151914118

APA StyleBlitstein-Mishor, E., Vigoda-Gadot, E., & Mizrahi, S. (2023). Navigating Emergencies: A Theoretical Model of Civic Engagement and Wellbeing during Emergencies. Sustainability, 15(19), 14118. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151914118