Abstract

This manuscript concerned customer recognition of biodegradable packaging. The authors of this study took up this issue due to its topicality and importance for enterprises and customers. The authors conducted a survey among consumers that showed how customers perceived 100% biodegradable packaging. It explored the role of these packages in marketing activities in the organic products market. The purpose of this article was to determine customer awareness of 100% biodegradable packaging. A diagnostic survey with a sample of 1000 respondents was used. The survey results indicated that customers declared environmentally friendly attitudes; however, they were not always able to recognize biodegradable packaging. Providing correct answers on this topic did not depend on gender, health status, or place of residence, only on the age and education of respondents. The research results may have both practical and theoretical implications. The results contribute to the development of management sciences. The conclusions from the manuscript allow producers, not only in food, to design new, biodegradable packaging in accordance with the feelings and expectations of consumers. Thus, it can contribute to increasing the demand for products in ecological packaging.

1. Introduction

The 20s of the 21st century are full of events and social attitudes related either to ecology or care for the environment. For example, research on consumer behavior in the COVID-19 age says that 45% of respondents avoid using plastic whenever possible [1]. The latest results of the cyclical EKOBarometer survey conducted by the SW Research studio in cooperation with the Akomex Group show that as many as 65% of Polish consumers support a prohibition on packaging food products in plastic. According to the majority of respondents, these packages should be replaced with paper or cartons. In addition, the European Union’s so-called Plastic Directive from 2019 imposed a prohibition on the sale and use of single-use plastic products, and Poland is one of the last EU countries that has not imposed any restrictions on their production so far. From 2025, further EU restrictions are expected to appear in this regard, including on plastic bottles (they will have to be produced from material that is at least 25% recycled) [2]. Another separate issue is a greenwashing practice, which many companies use to mislead consumers and create an environmentally friendly effect. Following the increasingly popular eco trend, brands increasingly want to be seen as “green” and concerned about our planet’s future, and this is not always accompanied by real actions. Many products are illegally labeled with ecological graphic symbols. Recent European Commission research revealed that false or misleading environmental communications (from the EU law point of view) are used by almost 50% of companies, and 37% of them use ambiguous or unclear terms related to the word “eco” [3]. However, when discussing today’s customers, it is impossible to ignore the fact that their purchasing decisions are increasingly influenced by eco-anxiety or even environmental depression. The reaction to these and other customer attitudes and expectations is the emerging trend to produce and sell more organic products.

Nowadays, society has started to wonder about the amount of waste that is produced around the world in the packaging of products from the FMCG industry, i.e., the so-called fast-moving goods industry. There is a global discussion on packaging, its usefulness, usability, reusability, and, above all, ecological aspects. Consumer movements are emerging that follow the zero-waste ideology. Consumers themselves start discussions and promote the idea of ecological packaging or even the lack of it. At the same time, the packaging market is growing, as packaging is one of the most effective marketing communication carriers and is often necessary to sell a product, and there are more and more products. The Polish packaging market is developing very dynamically [4]. The economy’s development, changes in people’s living conditions, or increased consumer awareness and demands are forcing businesses to continuously develop and search for new solutions in the effective presentation of products [5]. With increasing competitiveness in the market, the role of the packaging itself is also growing [6]. Packaging has an extremely important role in product promotion and distribution activities. The role of packaging in 21st century marketing is the subject of many theoretical and evidently practical considerations. Common packaging strategies to promote the product, distinguish products from competitors, communicate brand values, and target specific consumer groups include innovative, special edition, valued, and green packaging [7]. The subject of packaging management on climate change is dealt with by scientists around the world. Companies are competing in attracting target customers with various, often sophisticated, packaging forms. Simultaneously, ecological and zero-waste trends have emerged, frequently calling for the complete abandonment of packaging. It is indicated that plastic packaging does not decompose and has a negative impact on the environment. Society’s environmental awareness is constantly growing [8]. According to a Yale survey conducted in December 2018, 70% of Americans are “concerned” about climate change, 29% are “very concerned”, and 51% feel they are “helpless” [9]. At the end of 2019, global research indicated that 7.6 million people are concerned about negative climate change [10]. The packaging industry has faced scrutiny for the damaging effects certain materials, like plastic, have on the environment. Plastic pollution threatens wildlife and spreads toxins; the image of a plastic straw stuck in a turtle’s nose, for example, is a famous image many would recall when thinking about climate change. The manufacturing process of plastics also contributes to climate change and, according to the UK-based environmental organization Friends of the Earth, is responsible for 5% of greenhouse gas emissions [11]. This topic is approachable from many sides, even in the context of waste management. Comparisons were made between various technologies; a number of scenarios are considered to build up supply chains for the disposal process. The Life Cycles of Plastic packaging waste disposed via the Landfill, Incineration and Integrated Plastic Waste Management (IPWM) methods were compared and their environmental burdens calculated using the Eco-indicator 99 method [12]. In Poland, the first surveys dedicated to social problems of environmental protection, environmental awareness, and attitudes towards the environment were conducted in the 1980s [13]. The survey, conducted in 2010, showed that the biggest threats to the environment in Poland, according to respondents, were waste and packaging [14]. Meanwhile, a survey conducted in 2015 showed that more than 80% of Poles believe that they can contribute to improving the environment in their place of residence by taking individual actions (10% fewer people held a similar opinion in 2008) [15]. The findings of the research conducted in 2020 revealed that negatively framed messages were most effective in prompting effortful (but not effortless) pro-environmental intentions only when they were coupled with anthropomorphic cues (no differences between loss and gain messages were found when no anthropomorphism was used). These effects were replicated across two types of behaviors: water conservation and waste reduction [16].

More and more consumers are beginning to look for packaging that is also both safe and compliant with the requirements made by environmental movements, in addition to being attractive, innovative, and functional. Consequently, increasingly more products appear on store shelves beautifully packaged in materials made of natural, raw ingredients, or recyclable plastic [17]. Following this movement, the trend in eco-marketing began to appear in marketing, which could be defined by involving all marketing activities: those that appear as causes of environmental problems, and those that assist in solving environmental problems. In this way, environmental marketing studies both positive and negative aspects of marketing activities in connection with pollution, exhaustion of energy sources, and depletion of non-renewable resources [18]. In 2020, authors of the manuscript conducted research on customers’ noticing of eco-marketing activities in social media. The following conclusions emerged as a result: Eco-marketing activities appeared to attract notice in social media, but not yet as much as presumably desired. Gender was shown to correlate with respect to questions regarding the noticeability of zero-waste activities and pro-ecological activities in social media. Women display higher awareness of zero-waste and pro-ecological social media campaigns. In the aggregate, those who perceive zero waste as a lifestyle include women, who are more observant [19]. This was an inspiration for the author to do further research on the subject matter, this time focusing on packaging. From an eco-marketing perspective, it is important to determine whether customers actually know which packaging is truly biodegradable, whether they can distinguish it from others. Identifying which customers are doing better and which ones perhaps require additional educational efforts is also important.

2. Literature Review

According to their original purpose, packaging fulfills three main functions: protection, utility and communication [20]. It is the separation of the communication function that allows the packaging to be used for marketing purposes. Initially, it was a function regarded only as an information function, but, over time, it was noticed that it could be much broader. An interesting form, original color selection, or interesting graphics attract the eye and are memorable. The packaging is designed to create a desirable image of the product that will inspire confidence and persuade a purchase [6]. Packaging is correlated with activities aimed at building a strong brand [21]. At the same time, it is increasingly necessary to intensify sustainability and zero-waste activities in order to build it. It becomes appreciated by customers or even forced by them.

The intense evolution of global markets raises a demand to involve the pillars of sustainability (environment, society, and economy) in marketing decisions when aiming to satisfy the needs of the digitally empowered customer [22]. For this reason, the concept of eco-marketing, which is also called green marketing, or ecological marketing, has emerged. It responds to the necessity for the implementation of green practices and the resulting needs in the market. Green marketing refers to management tactics related to distribution—the chain of production to consumption—and reverse logistics, reducing packaging (decreasing transportation costs, optimizing carriers, and reducing material consumption), and using integrated transportation systems. In other words, green marketing involves the selection of channels that ensures that there is minimal environmental damage [23].

In this spirit, the zero-waste client movement was created, which directly challenged the common assumption of waste as a valueless and unavoidable by-product created at the end of the product’s life phase [24]. Zero waste acknowledges that waste is a “misallocated resource” or “resource in transition” that is produced during the intermediate phases of production and consumption activities, and thus it should be recirculated to production and consumption processes through reuse, recycling, reassembling, reselling, redesigning, or reprocessing [25]. The level of recycling solutions applied in different societies varies. For example, in 2017, Portugal and Poland generated around 150–170 kg of packaging waste per person and recycled just 50% of it, whereas Hungary and Iceland’s recycling rates were well below 50% [26].

Companies are increasingly interested in the concept of corporate social responsibility. They invest money in both economic and social development, which increases their competitiveness [27]. Companies have inevitably begun to design and produce a growing amount of packaging that is reusable or 100% biodegradable. This is often associated with additional production and design costs. However, research conducted in 2017 in Poland revealed that respondents do not attach much importance to eco-friendly product packaging [28]. Therefore, it seems important to verify whether the eco-marketing effect of such packaging on customers is profitable and noticeable. Research also indicates that environmental awareness is growing among people who want to feel closer to their food all over the world, even as they are becoming more urbanized [29]. Looking at the grocery market, one can see numerous zero-waste trends among customers, such as buying loose products for their own packaging. Hence, the marketing opportunities provided by the packaging are lost. The solution may be 100% biodegradable packaging. Biodegradable plastics decompose into carbon dioxide, water, and biomass.

This process is carried out by microorganisms. This packaging is made from organic, sustainably sourced, raw materials. For example, they can be made of cellulose, potato starch, or cornstarch [30]. Biodegradable plastics are useful in packaging, agriculture, gastronomy, consumer electronics, and the automotive industry [31]. It is increasingly used in industry. Biodegradable packaging is made of materials that can decompose easily after disposal under the action of microorganisms. This ability to decompose rapidly helps to control the build-up of waste in landfills and contributes to a safer and healthier environment [32]. Approximately 95–99% of plastic material for the production of packaging is manufactured from non-renewable sources (synthetic plastics) by petrochemical industries [33]. In 2019, the market for biodegradable plastic packaging was valued at USD 4.65 billion, and, by the end of 2025, it is expected to grow at a CAGR of 17.04%, reaching a market value of up to 12.06 million. This increase is due to growing environmental concerns and various government initiatives to reduce plastic waste [30]. Biodegradable plastics are promising alternatives to conventional, persistent plastics. The solution to the global plastic problem requires a multifaceted strategy, including reuse, recovery, prevention, disposal, and recycling. Within this strategy, biodegradable plastics are an important and essential component. The most relevant applications of biodegradable plastics are packaging, including food packaging, single-use plastics, and agricultural mulch films [34].

It is worth considering which customer groups are most aware of zero waste and biodegradable packaging. This has significance for the companies’ eco-marketing activities. The Ministry of Climate and Environment’s long-term research program is conducting research into the awareness and environmental behavior of the Polish population. The research indicates that the percentage of Polish residents who believe that improving the environment depends on everyone’s activities is increasing [35]. It is worth checking how this relates to individual markets/industries. Therefore, it was decided in the article to verify research hypothesis H1: issues related to the environmental sustainability of food products are largely relevant to customers.

Research conducted to date indicates that it is women who are more ecologically engaged. Eco-marketing activities should be predominantly targeted at women because they are more likely to take note of the message [19]. In this article, referring to the above, the following research hypothesis H2 is formulated: women are better at recognizing 100% biodegradable packaging. Generally, research indicates that environmental awareness is relatively low in Polish society. Knowledge sources on environmental problems and environmental protection are most often the media (95% of indications); these include news programs, daily newspapers, and opinion-forming magazines, less frequently specialist magazines. Younger respondents indicated school and subjects related to biology and geography in addition to media [28]. Many previous studies indicate the ecological sensitivity of young consumers. For example, Herrmann et al. [36] writes about this, proving that consumers under 30 are willing to pay for packaging that they perceive to be sustainable and are not willing to pay for packaging that they perceive to be non-sustainable or about which they are uncertain. Chirilla’s [37] research also indicated that the most sustainable groups were mainly composed of females, whereas less sustainable consumers were mainly the youngest. It is worth observing the youngest customers and, therefore, a verification of hypothesis H3 was undertaken: younger customers are better at recognizing 100% biodegradable packaging. In general, the recognition of biodegradable packaging by customers in the article’s authors’ assumption became an indicator of the actual development of pro-environmental attitudes by customers. In a way, this verifies their declaration, as it tests their actual knowledge. On this basis, another research hypothesis H4 was formulated: customers who consider the environmental sustainability of food products to be important are better at identifying 100% biodegradable packaging. Considering other demographic characteristics and respondents’ health statuses in the self-assessment, the following research hypothesis is further formulated: H5: customers describing their health status as bad or very bad are better at identifying 100% biodegradable packaging. In large cities, the issue of waste segregation is more widespread, and there is a better flow of information on the need to protect the environment against pollution with too much garbage. Even the concept of urban ecology was formulated. The goal of urban ecology is to achieve a balance between human culture and the natural environment [38]. Eco-innovations appear first in cities [39]. Consumers have a chance to get acquainted with them and get used to them. This allows us to risk another hypothesis: H6: customers from larger cities are better at recognizing 100% biodegradable packaging.

Herrman’s [36] research also showed that the level of education influenced pro-ecological behavior and reflection on what consumers can do for the climate. He backed this up with his research by Łęska and Kuś [40], which stated that students were characterized by a high level of ecological awareness and a sense of responsibility for it, and they are informed and pragmatic consumers. Hence, the following hypothesis can be formulated: H7: higher educated customers better identify 100% biodegradable packaging.

Packaging visually communicates a certain marketing message to customers. The global literature emphasizes that researchers continue to document the wide range of crossmodal correspondences that underpin the links between individual visual packaging design features and specific properties of food and drink products (such as their taste, flavor, or healthfulness), and the ways in which marketers are now capitalizing on such understandings to increase sales [41]. As packaging in the discussed context has a visual impact on the customer, the validity of hypothesis H8 was also tested: customers who believe that product packaging graphics can indicate the environmental properties of the product better identify 100% biodegradable packaging.

Methods and Analysis

The research problem addressed in the manuscript was the identification of determinants of customers’ recognition of biodegradable packaging. The survey was conducted in January 2021 using a diagnostic survey method. The questionnaire was designed by the authors of the article. It was distributed by a professional research agency. A total of 1000 adult Polish residents participated in the survey. Calculation of the sample size was carried out taking into account the following assumptions: A consumer is a natural person who performs a legal transaction with an entrepreneur not directly related to his business or professional activity. There were just over 37 million adult Poles in Poland at the time of the survey. According to the law, they could be called consumers. With such a size of the general population, we assumed a 5% error and a 1% significance level. The sample size for a finite population is 1037. A study conducted on a sample of 1000 respondents could be considered representative for a given population. The research sample structure is presented in detail in Table 1.

Table 1.

Research sample characteristics.

Statistical analysis of the test results was performed in the R Studio program. The relationship between the answers provided by the respondents and (respectively) gender, level of education, place of residence, age group, or average income per capita was tested with the χ2 test (with Yates’ correction for classes with a smaller number than 10). In all issues, a null hypothesis was created about the lack of dependence between the groups (taking into account the divisions according to the metrics) against the alternative hypothesis that such a relationship existed. The significance level of p = 0.05 was assumed in the entire analysis.

For the purpose of this article, the answers to the metric questions and “How important are the issues related to the environmental sustainability of food products to you?” were analyzed. It was possible to indicate answers on a scale of 1 to 5, with 1 meaning “I am not interested in environmental issues” and 5 meaning “I am very interested in environmental issues”. Based on the results of the χ2 test, the null hypothesis was rejected for the question “How important are the issues related to the environmental sustainability of food products to you?” It turned out that the interest in ecology itself depended on the gender, age, education, and professional and family statuses of the respondents, whereas paying attention to the ecology of the product when shopping depended on their gender and family status. From the point of view of the considerations carried out in this book, the most significant factor was that the majority of women were interested in both issues related to ecology and the purchase of organic products. They were mainly interesting to younger people below 44 years of age. In addition, people with children (both families and single parents) paid more attention to these two issues. There was a correlation between education and the approach to ecological issues. At the same time, more positive answers were given to the mere interest in ecological issues and less to making purchasing decisions based on the environmental performance of the product.

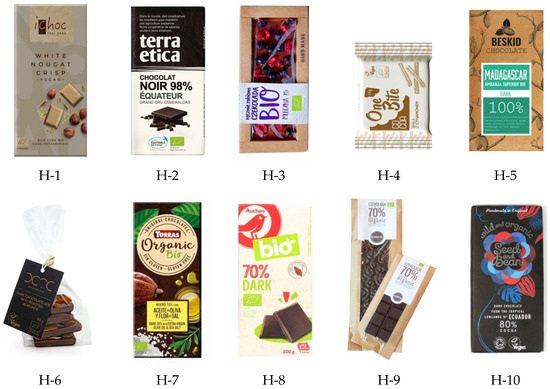

The answers to the question “Which of the following product packaging do you think is 100% biodegradable?” were also considered. In the possible answers, customers were shown various packaging of food products: mineral water, mirepoix, apple juice, potatoes, butter, milk, yoghurt, chocolate, flour, jam, and oatmeal. Both fully biodegradable and non-biodegradable packaging appeared in each group. An example is shown in Figure 1. The possibility was given to indicate 1 to 3 products from each group.

Figure 1.

Example of an answer to the question “Which of the following product packaging do you think is 100% biodegradable (please indicate 1 to 3 products from each group)?”

Respondents were asked to indicate which packaging was 100% biodegradable (respondents could select more than one answer). For the products shown in the questionnaire, more than one answer could be correct. For example, for chocolate (Figure 1), the correct answers were H3, H5, and H9. A discussion of the responses in relation to each package is provided in Table 2.

Table 2.

Quantitatively correct answers for individual product packaging.

Respondents were also asked whether, in their opinion, the graphics of a product’s packaging could be indicative of the product’s environmental properties. A typical Likert scale was used in the response.

3. Results

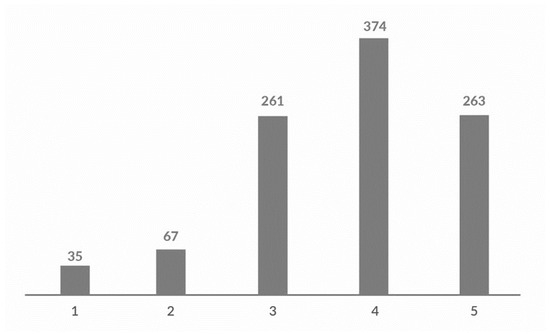

In response to the question “How important are the issues related to the environmental sustainability of food products to you?”, respondents marked answers indicating affirmatively in the vast majority of cases. The number of responses is shown in detail in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The number of responses to the question “How important are the issues related to the environmental sustainability of food products to you?” together with the indications on a scale from 1 to 5.

In the case of the question to identify a 100% biodegradable product, respondents were given the opportunity to demonstrate their knowledge. The results in relation to individual products are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Results of correct answers to the question “Which of the following product packaging do you think is 100% biodegradable?”

Three products were not included in the table above: jam, as none of the answers were correct; flour, where, apart from one answer, all were correct, and the incorrect one was chosen by only 60 people; and milk, where none of the packaging was 100% biodegradable, and 883 people chose the only recyclable one of the 10 presented. In the table, answers illustrating the opinion of less than 25% of the respondents are highlighted in red. These indicate that certain packaging confused respondents about biodegradability, and these should be investigated first. These are the packages shown in Figure 3. They were 100% biodegradable, but the respondents mostly failed to notice this.

Figure 3.

Packaging whose biodegradability was noted by respondents the least.

Considering all the correct answers, except for flour, for which the packaging was mostly biodegradable and would have disturbed further analysis, 21 correct answers were possible among all the packaging shown. There were 1000 respondents in the entire survey population, so they should have given 21,000 correct answers. There were 7755 of them, accounting for 36.93% of the correct answers in the surveyed population. The most correct answers (15) were given by one person (0.001% of the population). More than half of the correct answers were given by 170 people (17% of the population). However, three people (0.003% of the population) did not provide any correct answer.

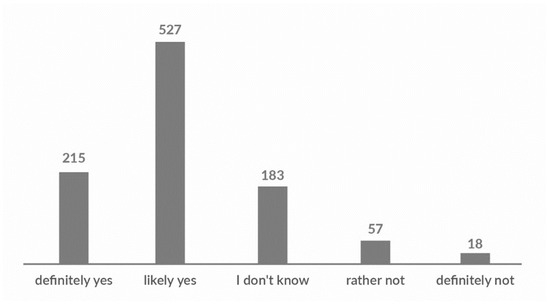

In response to the question “In your opinion, can the graphics of a product’s packaging prove the environmental properties of the product?”, the customers mostly agreed with this statement. The number of indicated responses is shown in detail in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

The number of responses to the question “In your opinion, can the graphics of a product’s packaging prove the environmental properties of the product?”

To verify hypothesis H1, issues related to the environmental sustainability of food products are largely relevant to customers, it was necessary to analyze the answers to the question “How important are environmental issues related to food products to you?” With the results presented in Figure 1, it is noticeable that the respondents mostly believed that issues related to the environmental sustainability of food products were important to them. Therefore, hypothesis one was confirmed.

To verify hypothesis H2, women are better at recognizing 100% biodegradable packaging, it was necessary to examine how many correct answers women marked. After rejecting a product like flour, which had 90% biodegradable packaging, there were 21 correct answers remaining, which, with the number of women in the survey, should have given 10,521 correct answers. Women gave 4030 correct answers from this set, and men gave 3725 of the 10,479 correct answers (the number of men surveyed was less than the number of women). The percentage was 38.3% of correct answers for women and 35.5% for men. This seemed to be an inconclusive result for this hypothesis.

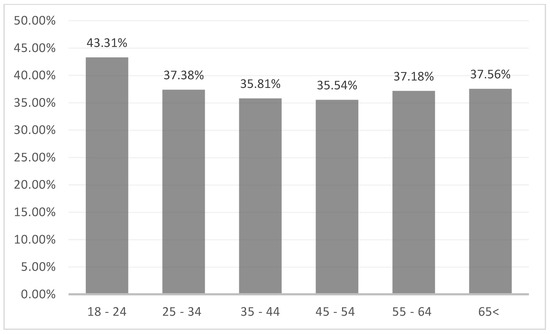

In order to verify hypothesis H3, younger customers are better at recognizing 100% biodegradable packaging, it was necessary to examine how different age groups responded to the question regarding the packaging’s biodegradability. The results obtained are shown in Table 4 and Figure 5.

Table 4.

Numbers of correct answers to the question about identifying 100% biodegradable packaging by age group.

Figure 5.

Distribution of correct answers to the question on identifying 100% biodegradable packaging by age group.

The answers by age group did not differ strongly, actually corresponding to the percentage of correct answers in the entire surveyed population, but it was clear that the awareness of biodegradability was highest in the 18–24 age group, i.e., the youngest. Therefore, hypothesis 3 could be considered confirmed.

To verify hypothesis H4, customers who consider the environmental sustainability of food products to be important are better at identifying 100% biodegradable packaging, the relationship between answers to the question “How important are environmental issues of food products to you?” with correct indications of biodegradable packaging should be analyzed. In this case, 637 people marked responses indicating that issues related to the environmental sustainability of food products were important or very important to them. These people marked 5066 correct answers regarding 100% biodegradable packaging. They should have marked 13,377 correct answers, representing 37.87% response efficiency in this case, which corresponded to the percentage of correct answers in the surveyed population. A total of 102 people declared that issues related to the environmental sustainability of food products were not important to them. They indicated 779 answers out of 2142 that were correct. Accordingly, this represented 36.37% of the response efficiency in this case, which corresponded to the percentage of correct responses in the surveyed population. It appeared that the fourth hypothesis could not be positively verified, as the dependency suggested by the hypothesis did not occur.

To verify hypothesis H5, customers describing their health status as bad or very bad are better at identifying 100% biodegradable packaging, it was necessary to determine what was the percentage of correct answers in this group. Only 67 respondents described their health condition as bad or very bad. They should have marked a maximum of 1407 correct answers. They marked 500 answers correct. Accordingly, their effectiveness was 35.54%, which corresponded to the percentage of correct answers in the surveyed population, whereas those who considered their health to be good and very good were 597 people and marked 4545 out of 12,159 correct responses for their group, accounting for 37.37% of effective responses. The verification of the fifth hypothesis seemed to be inconclusive in such a case.

To verify hypothesis H6, customers from larger cities are better at recognizing 100% biodegradable packaging, it was necessary to examine how residents of cities over 250,000 responded to the question about the biodegradability of packaging. There were 236 people, and they marked 1804 of the 4956 correct answers for this group. This represented 36.40%, which corresponded to the percentage of correct answers in the surveyed population. To attempt to verify this hypothesis, the remaining groups were analyzed in relation to place of residence and the results are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

The number of correct answers to the question of identifying 100% biodegradable packaging given by respondents depending on their place of residence.

According to the results presented in Table 5, it appears that hypothesis 6 could not be verified since providing correct answers did not depend on the place of residence; all the results were close to the percentage of correct answers in the general population.

To verify hypothesis H7, higher educated customers better identify 100% biodegradable packaging, it was necessary to analyze responses to the question regarding biodegradable packaging across all education groups. The results are presented in Table 6.

Table 6.

Number of correct answers to the question of identifying 100% biodegradable packaging given by respondents according to education.

Also, in this case, the survey indicated that slightly more people with higher education answered the question correctly. Hence, the seventh hypothesis could be considered confirmed.

In order to verify hypothesis H8, customers who believe that product packaging graphics can indicate the environmental performance of a product better identify 100% biodegradable packaging, it was necessary to examine what answers were given by those respondents who, in the question “In your opinion, can the graphics of product’s packaging prove the environmental properties of the product?”, marked the answer “definitely yes” or “rather yes”. There were 742 such people. They should have marked 15,582 correct answers, and they did so in 5989 cases, which was 38.44% of the effective answers. It could be claimed that this was above the population’s average, and, therefore, it was concluded that hypothesis 8 was confirmed.

4. Discussion

The results of the research hypothesis verification are summarized in Table 7.

Table 7.

Hypothesis verification.

The inconclusive verification of some hypotheses is surprising since, for example, previous repeated studies have shown that women have a stake in the environment, and this stake is reflected in the degree to which they care about natural resources. Ecofeminism refers to women’s and feminist perspectives on the environment—where the domination and exploitation of women, poorly resourced people, and nature are at the heart of the ecofeminist movement [42]. Meanwhile, in the conducted research, it cannot be conclusively concluded that women are better at recognizing 100% biodegradable packaging. Their advantage is small. Perhaps, this is due to the fact that it is no longer only women who are concerned about the well-being of the environment nowadays but also men have started to become concerned about it. Neither health statuses nor places of residence seemed to particularly affect the recognition of 100% biodegradable packaging. This could also be due to an equalization of pro-environmental trends across all social groups. According to the report “Ecological Attitudes—Survey of Attitudes and Opinions of Poles 2020”, in order to heal the world’s ecological situation, emphasis should first be placed on segregating garbage, recycling, and radically reducing the use of packaging and products made of plastic. This is equally important for respondents from small, medium, and large cities [43]. This contradicted several years of research on a nationwide sample conducted by T. Burger in 2005 [13]. According to him, Poles living in rural areas and in the east of the country were characterized by the lowest levels of the pro-environmental attitude index [44].

In Poland, the first study on social problems of environmental protection, environmental awareness, and attitudes towards the environment was conducted in the 1980s [15]. The hypothesis verification in this article indicates that modern consumers are increasingly environmentally aware and mostly declare that an ecological approach to life is not unfamiliar to them. Therefore, it must be assumed that a consumer in the 2020s will make decisions based on personal views, which include caring for the environment. A number of activities can be undertaken as part of green marketing to enable customers to make conscious decisions when purchasing products in ecological packaging. Research indicates that customers claiming to care about the environment are not always able to identify 100% biodegradable packaging. This is due to poor knowledge of the latest technological developments regarding biodegradable materials and may be the reason why some packaging is not identified as biodegradable. Foil in the minds of most consumers is still a product with no ecological properties. As it is predicted that information on the environmental impact of packaging will be a factor in attracting customers’ attention in the next 10 years, the authors of this study see potential in the graphic and information packaging layer. Using biodegradable materials, e.g., cellulose film, as a bioplastic clearly marked on the packaging, together with highlighting the compostable properties of the mentioned cellulose film, would significantly influence the perception of such a product and its packaging as 100% biodegradable. Customers also sometimes confuse biodegradability with recycling. Therefore, educational activities are important in this area, both regarding the latest technological developments in biodegradable material production and the recycling issue. Companies concerned with sustainability should undertake these activities to encourage customers to buy products with environmentally friendly packaging. Marketing communication activities on this topic should be undertaken. Information on the packaging’s biodegradability should be clear, unambiguous, and encouraging to customers. Based on this research, it is possible to create a marketing communication model, building on communication through packaging that responds to the needs of customers and the modern world in ecological terms. In the light of recent EU legislation and Europe’s aspiration to become climate neutral by 2050, such action seems almost a necessity. The new regulations are intended to promote reusable and recyclable packaging solutions (the EU’s aim is to make packaging fully recyclable by 2030). This will force manufacturers to clearly label both the product and the packaging materials. This will involve the introduction of packaging design criteria and clear labelling of which packaging is compostable and which is recyclable. This creates new marketing opportunities, especially in terms of creating pro-quality awareness among consumers.

5. Conclusions

The research undertaken in the article can be extended to other markets and repeated in other countries. The differences between the perceptions of green packaging by different nationalities in different cultures may prove interesting. The survey can also be subjected to further in-depth statistical analysis. Individual products whose packaging was presented to respondents can also be analyzed separately. A certain limitation of the present survey is that actual customers may have different understandings of the biodegradability concept. Not every product is suitable for such packaging, which is a major constraint for manufacturers. Respondents’ declarations of an environmentally friendly approach to shopping may be based on their willingness rather than their actual attitudes, and it is impossible to check this with a survey questionnaire. In addition, conducting a survey among Polish consumers may be considered a limitation, but, despite this, the survey is not of a local nature, as the issues raised are important for all European countries and not only Poland. Virtually anywhere in the world, customers can encounter both biodegradable and non-biodegradable packaging, and it is important to determine whether they recognize them correctly; this research can be generalized or be a starting point for extended research. The conducted review of world literature indicates the global scope of the discussed topic.

An alternative to 100% biodegradable packaging could be the use of circular economy solutions, for example, tactically, companies can use pricing actions, such as rebates for returning recyclable packaging or charging higher prices for environmentally unfriendly products [45]. It is also worth exploring customer attitudes toward recyclable packaging.

The present research may be applicable to companies that are environmentally conscious and undertake green marketing activities. Customer reactions to different packaging can be identified. These companies should also focus on educating their customers in this regard.

The research and considerations carried out in the manuscript allow for the development of practical and theoretical implications. The topic discussed is important for producers of packaging and FMCG products around the world. It is important in the context of environmental protection and corporate social responsibility as well as sustainable development. Knowledge about consumer behaviors and their awareness has been expanded, which relates to global markets.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.B. and A.S.; Methodology, A.B. and A.S.; Software, A.B.; Validation, A.B.; Formal analysis, A.B.; Investigation, A.B.; Resources, A.B.; Data curation, A.B.; Writing—original draft, A.B. and A.S.; Writing—review & editing, A.B. and A.S.; Visualization, A.B. and A.S.; Supervision, A.B.; Project administration, A.B.; Funding acquisition, A.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to at the Lublin University of Science and Technology, the research ethics committee is just starting its work and is being established. The research was done earlier. The survey was carried out in accordance with PKJPA standards. Therefore, the respondents, before starting the survey, are informed that the survey is anonymous, which means that individual responses are not associated with specific persons. Each of the respondents is given only a sequential number in the results database. The respondents were also informed about the purpose of data collection—research purposes.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Filho, W.L.; Voronova, V.; Kloga, M.; Paço, A.; Minhas, A.; Salvia, A.L.; Ferreira, C.D.; Sivapalan, S. COVID-19 and Waste Production in Households: A Trend Analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 777, 145997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 65% Polaków Popiera Wdrożenie Zakazu Pakowania Żywności w Plastik. Available online: https://akomex.pl/aktualnosci/65-polakow-popiera-wdrozenie-zakazu-pakowania-zywnosci-w-plastik/ (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- Zielone Strony Biznesu. Greenwashing Czyli Ekościema. Available online: https://mycompanypolska.pl/artykul/zielone-strony-biznesu-greenwashing-czyli-ekosciema/7968 (accessed on 17 December 2022).

- Kowalska, A. Key Drivers Behind the Growth of the Polish Packaging Market in 2005–2012—Macroeconomic Approach. Olszt. Econ. J. 2014, 9, 345–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakour, M.J.; Swager, C.M. Vulnerability-plus Theory. In Creating Katrina, Rebuilding Resilience; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 45–78. ISBN 978-0-12-809557-7. [Google Scholar]

- Gościańska, K. Rola Opakowań w Marketingu. Available online: https://marketerplus.pl/rola-opakowan-marketingu/ (accessed on 15 April 2023).

- Ford, A.; Moodie, C.; Hastings, G. The Role of Packaging for Consumer Products: Understanding the Move towards ‘Plain’ Tobacco Packaging. Addict. Res. Theory 2012, 20, 339–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlap, R.E.; Van Liere, K.D. The “New Environmental Paradigm”. J. Environ. Educ. 1978, 9, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dróżka, W. Coraz Więcej Osób Panicznie Boi Się Zmian Klimatycznych—Alarmują Psychologowie. Available online: https://zdrowie.radiozet.pl/psychologia/lek-i-nerwice/Lek-ekologiczny-eco-anxiety-i-depresja-klimatyczna-czym-sa (accessed on 13 March 2023).

- Eco-Anxiety Is on The Rise—But That’s Not Necessarily a Bad Thing. Available online: https://www.mindbodygreen.com/articles/what-is-eco-anxiety (accessed on 13 March 2023).

- Paige, J. How Packaging Companies Could Drive Climate Change Action: GlobalData. Available online: https://www.packaging-gateway.com/features/how-packaging-companies-could-drive-climate-change-action-globaldata/ (accessed on 4 August 2023).

- Akinola, A.A.; Adeyemi, I.A.; Adeyinka, F.M. A Proposal for the Management of Plastic Packaging Waste. J. Environ. Sci. Toxicol. Food Technol. 2014, 8, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burger, J.M. Desire for Control, Locus of Control, and Proneness to Depression. J. Personal. 1984, 52, 71–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nycz-Wróbel, J. Świadomość Ekologiczna Społeczeństwa i Wynikające z Niej Zagrożenia Środowiska Naturalnego (Na Przykładzie Opinii Mieszkańców Województwa Podkarpackiego). Zesz. Nauk. Politech. Rzesz. Ser. Ekon. Nauk. Humanist. 2012, 19, 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kłos, L. Świadomość Ekologiczna Polaków—Przegląd Badań. Zesz. Nauk. Uniw. Szczecińskiego Stud. Pr. Wydziału Nauk. Ekon. Zarządzania 2015, 42, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpinska-Krakowiak, M.; Skowron, L.; Ivanov, L. “I Will Start Saving Natural Resources, Only When You Show Me the Planet as a Person in Danger”: The Effects of Message Framing and Anthropomorphism on Pro-Environmental Behaviors That Are Viewed as Effortful. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binda, A. Recykling i Ochrona Środowiska: “Złote Zasady” Przy Projektowaniu Opakowań Produktów Kosmetycznych. Opakowanie 2013, 9, 53–55. [Google Scholar]

- Henion, K.E.; Kinnear, T.C. Ecological Marketing; American Marketing Association: Chicago, IL, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Bojanowska, A.; Kulisz, M. Polish Consumers’ Response to Social Media Eco-Marketing Techniques. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockhart, H.E. A Paradigm for Packaging. Packag. Technol. Sci. 1998, 10, 237–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agariya, A.K.; Johari, A.; Sharma, H.K.; Chandraul, U.N.S.; Singh, D. The Role of Packaging in Brand Communication. Int. J. Sci. Eng. Res. 2012, 3, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Amoako, G.K.; Dzogbenuku, R.K.; Doe, J.; Adjaison, G.K. Green Marketing and the SDGs: Emerging Market Perspective. MIP 2022, 40, 310–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen-Viet, B. The Impact of Green Marketing Mix Elements on Green Customer Based Brand Equity in an Emerging Market. APJBA 2023, 15, 96–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaman, A. Zero-Waste: A New Sustainability Paradigm for Addressing the Global Waste Problem. In The Vision Zero Handbook; Edvardsson Björnberg, K., Belin, M.-Å., Hansson, S.O., Tingvall, C., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 1–24. ISBN 978-3-030-23176-7. [Google Scholar]

- Zaman, A.; Ahsan, T. Zero-Waste: Reconsidering Waste Management for the Future, 1st ed.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK; Oxon, MD, USA; New York, NY, USA, 2019; ISBN 978-1-315-43629-6. [Google Scholar]

- Eurostat. Packaging Waste Statistics. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Packaging_waste_statistics (accessed on 14 February 2022).

- Kownacka, E.; Malik, K. Koncepcja Zero Odpadów Jako Element Społecznej Odpowiedzialności Biznesu. Zesz. Nauk. Politech. Poznańskiej. Organ. Zarządzanie 2013, 60, 43–53. [Google Scholar]

- Patrzałek, W. The Importance of Ecological Awareness in Consumer Behavior. Wydaw. Uniw. Ekon. We Wrocławiu 2017, 13, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erälinna, L.; Szymoniuk, B. Managing a Circular Food System in Sustainable Urban Farming. Experimental Research at the Turku University Campus (Finland). Sustainability 2021, 13, 6231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, S.; Yaqoob, M.; Aggarwal, P. An Overview of Biodegradable Packaging in Food Industry. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2021, 4, 503–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshood, T.D.; Nawanir, G.; Mahmud, F. Sustainability of Biodegradable Plastics: A Review on Social, Economic, and Environmental Factors. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2022, 42, 892–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicasio, F. 9 Biodegradable Packaging Materials That Can Replace Plastic. Available online: https://noissue.co.nz/blog/biodegradable-packaging-materials-that-can-replace-plastic/ (accessed on 14 February 2022).

- Mangaraj, S.; Yadav, A.; Bal, L.M.; Dash, S.K.; Mahanti, N.K. Application of Biodegradable Polymers in Food Packaging Industry: A Comprehensive Review. J. Package Technol. Res. 2019, 3, 77–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flury, M.; Narayan, R. Biodegradable Plastic as an Integral Part of the Solution to Plastic Waste Pollution of the Environment. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2021, 30, 100490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Research on Environmental Awareness and Behavior of Polish Residents—Tracking Study Report; National Fund for Environmental Protection and Water Management, Ministry of Climate and Environment: Warsaw, Poland, 2020.

- Herrmann, C.; Rhein, S.; Sträter, K.F. Consumers’ Sustainability-Related Perception of and Willingness-to-Pay for Food Packaging Alternatives. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 181, 106219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirilli, C.; Molino, M.; Torri, L. Consumers’ Awareness, Behavior and Expectations for Food Packaging Environmental Sustainability: Influence of Socio-Demographic Characteristics. Foods 2022, 11, 2388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonnell, M.J.; MacGregor-Fors, I. The Ecological Future of Cities. Science 2016, 352, 936–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szelągowska, A.; Bryx, M. (Eds.) Eco-Innovations in Cties, 1st ed.; CeDeWu Sp.: Warszawa, Poland, 2015; ISBN 978-83-7556-814-1. [Google Scholar]

- Łęska, M.; Kuś, A. Ecological Awareness in the Behaviour of Young Consumers—Students of the Faculty of Economic and Technical Sciences of Pope John Paul II State School of Higher Education in Biała Podlaska. Econ. Reg. Stud./Stud. Ekon. Reg. 2018, 11, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, C.; Van Doorn, G. Visual Communication via the Design of Food and Beverage Packaging. Cogn. Res. 2022, 7, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiggins, J. Changing the Boundaries: Women-Centered Perspectives on Population and the Environment; Island Press: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Postawy Ekologiczne. Badania Postaw i Opinii Polek i Polaków. Available online: https://bluemedia.pl/storage/eco/raport_eko_10lite.pdf (accessed on 22 February 2022).

- Perepeczko, B. Pro-Environmental Attitudes of Rural Residents and Their Determinants. Zesz. Nauk. SGGW Warszawie Ekon. Organ. Gospod. Żywnościowej 2012, 8, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonidou, C.N.; Katsikeas, C.S.; Morgan, N.A. “Greening” the Marketing Mix: Do Firms Do It and Does It Pay Off? J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2013, 41, 151–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).