Green Tourism and Sustainability: The Paiva Walkways Case in the Post-Pandemic Period (Portugal)

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Conceptual Framework

2.1. Green Tourism: Towards Sustainability

2.2. Strategies for Green Tourism Implementation Focused on the Sustainable Development Goals

2.3. The Walkways: A New Trend in Green Tourism

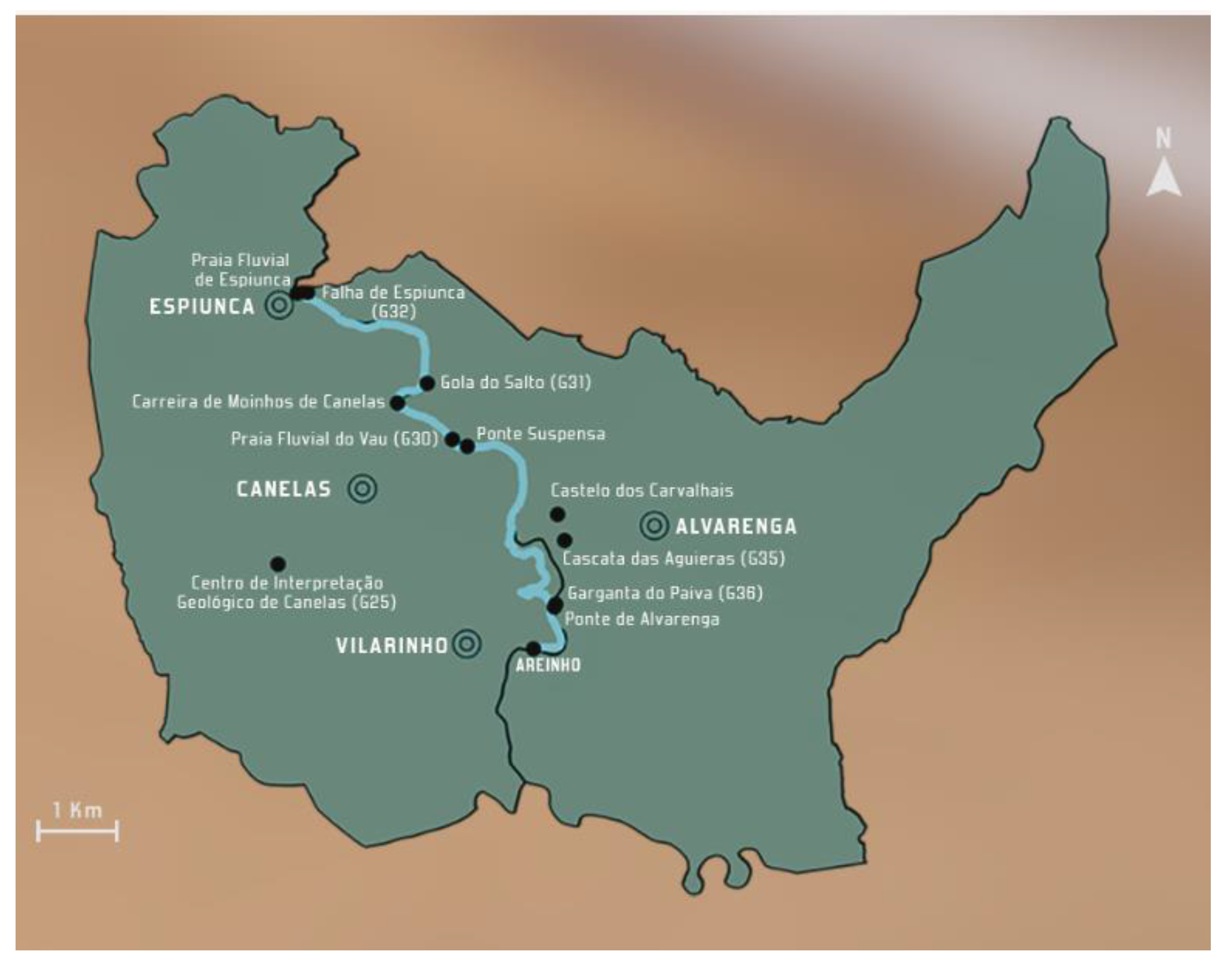

2.4. The Paiva Walkways Case

3. Methodology

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. The Paiva Walkways as an Engine of Economic and Social Development

4.2. Paiva Walkways and Their Strategic Vision of Sustainable Tourism

4.3. The Paiva Walkways as an Example of Best Practices in the Development of Green Tourism

5. Conclusions and Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mowforth, M.; Munt, I. Tourism and Sustainability: New Tourism in the Third World; Routledge: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, H.; Sirakaya, E. Sustainability indicators for managing community tourism. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 1274–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, R. Managing Tourism—A Missing Element Gestión turística asignatura pendiente. PASOS Rev. De Tur. Y Patrim. Cult. 2022, 20, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z. Sustainable tourism development: A critique. J. Sustain. Tour. 2003, 11, 459–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavaco, C. Territórios de turismo. Rev. Tur. Desenvolv. 2018, 20, 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNWTO. Global Code of Ethics for Tourism; UNWTO: Madrid, Spain, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Mota, A. Turismo de Natureza como Fator Impulsionador da Preservação Ambiental: O Caso dos Passadiços do Paiva. Master’s Thesis, University of Porto, Porto, Portugal, 2019. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10216/123514 (accessed on 2 December 2022).

- Oliveira, D.; Tavares, F.; Pacheco, L. Os Passadiços do Paiva: Estudo Exploratório do seu Impacto Económico e Social. Front. J. Soc. Technol. Environ. Sci. 2019, 8, 242–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Work on Green Growth 2020. Available online: https://issuu.com/oecd.publishing/docs/gg_brochure_2019_web (accessed on 2 December 2022).

- United Nations Report. Our Common Future; Oxford University: Oxford, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, G.; Morpeth, N. Local Agenda 21: Reclaiming community ownership in tourism stalled process? In Tourism and Sustainable Community Development; Richards, G., Hall, D., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2001; pp. 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiper, N. Environmental impacts and ecosystems for tourism. Tour. Manag. 1995, 16, 160–189. [Google Scholar]

- Middleton, V.; Hawkins, R. Sustainable Tourism: A Marketing Perspective; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Fayos-Solà, E. Sustainability and Shifting Paradigms in Tourism. PASOS Rev. De Tur. Y Patrim. Cult. 2015, 13, 1299–2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toubes, D.R.; Araújo-Vila, N. A review research on tourism in the green economy. Economies 2022, 10, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.H.; Hsu, I.C.; Lin, T.Y.; Tung, L.M.; Ling, Y. After the epidemic, is the smart traffic management system a key factor in creating a green leisure and tourism environment in the move towards sustainable urban development? Sustainability 2022, 14, 3762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayos-Solà, E.; Alvarez, M.; Cooper, C. Tourism as an Instrument for Development: A Theoretical and Practical Study; Emerald Group Publishing Ltd.: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNWTO. Tourism in the Green Economy—Background Report; United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) and World Tourism Organization (UNWTO): Madrid, Spain, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- UNWTO. World Tourism Organization and United Nations Development Programme (2017), Tourism and the Sustainable Development Goals—Journey to 2030; UNWTO: Madrid, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Dhahri, S.; Omri, A. Entrepreneurship contribution to the three pillars of sustainable development: What does the evidence really say? World Dev. 2018, 106, 64–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turismo de Portugal. Estratégia Turismo 2027; TP: Lisboa, Portugal, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Tawiah, V.; Zakari, A.; Adedoyin, F.F. Determinants of green growth in developed and developing countries. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 39227–39242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gispert, O.B.; Clavé, S.A. Dimensions and models of tourism governance in a tourism system: The experience of Catalonia. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2020, 17, 100465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagodiienko, V.; Sarkisian, H.; Dobrianska, N.; Krupitsa, I.; Bairachna, O.; Shepeleva, O. Green tourism as a component of sustainable development of the region. Manag. Theory Stud. Rural. Bus. Infrastruct. Dev. 2022, 44, 254–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.; Wang, R.; Ling, H.; Chu, J. Implementing for innovative management of green tourism and leisure agriculture in Taiwan. Int. J. Organ. Innov. 2020, 13, 210–220. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Bai, Y.; Alatalo, J.M. Impacts of rural tourism-driven land use change on ecosystems services provision in Erhai Lake Basin, China. Ecosyst. Serv. 2020, 42, 101081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulaali, H.S.; Usman, I.M.S.; Al-Ruwaishedi, M.R. A review on sustainable and green development in the tourism and hotel industry in Malaysia. J. Adv. Res. Dyn. Control. Syst. 2019, 11, 854–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahid, J. The implementation of green policy towards the development of sustainable green tourism village at Bone-Bone, Enrekang, South Sulawesi. AIP Conf. Proc. 2019, 212, 0400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.P.; Bui, V.D. Green Marketing Strategy as a Sustainable Solution to Tourism Development in Vietnam. Webology 2021, 18, 116–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousaf, Z.; Radulescu, M.; Sinisi, C.I.; Serbanescu, L.; Paunescu, L.M. Harmonization of green motives and green business strategies towards sustainable development of hospitality and tourism industry: Green environmental policies. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, P. Walking & Cycling: Uma Nova Geografia Do Turismo; Imprensa da Universidade: Coimbra, Portugal, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C. Changing paradigms and global change: From sustainable to steady-state tourism. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2010, 35, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, S.; Gao, M.; Kim, H.; Shah, K.; Pei, S.; Chiang, P. Advances and challenges in sustainable tourism toward a green economy. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 635, 452–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. OECD Tourism Trends and Policies 2022; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becken, S.; Loehr, J. Tourism governance and enabling drivers for intensifying climate action. J. Sustain. Tour. 2022, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beautiful Green. Website A Beautiful Green—The Sustainable Development Goals. (2023, June 24). Available online: https://www.abeautifulgreen.com/en/the-sustainable-development-goals (accessed on 26 June 2023).

- Lee, S.; Honda, H.; Ren, G.; Lo, Y. The Implementation of Green Tourism and Hospitality. J. Tour. Hosp. 2016, 4, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, A. Strategies for sustainable tourism development: The role of the concept of carrying capacity. Soc. Econ. Stud. 2002, 51, 61–98. [Google Scholar]

- Ramchurjee, N.; Ramchurjee, E. Tourists Becoming Increasingly Aware of Green Tourism: Tourist Intention to Choose Green Hotels in Bangalore, India. In Green Business: Concepts, Methodologies, Tools, and Applications; I. Management Association, Ed.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2019; pp. 838–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majewski, L.; Koontz, L. The economic role of nature tourism in U.S. national parks. Geogr. Rundsch. 2022, 74, 22–26. [Google Scholar]

- Siegel, L.; Tussyadiah, I.; Scarles, C. Exploring behaviors of social media-induced tourists and the use of behavioral interventions as salient destination response strategy. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2023, 27, 100765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tom Dieck, D.; Tom Dieck, M.; Jung, T.; Moorhouse, N. Tourists’ virtual reality adoption: An exploratory study from Lake District National Park. Leis. Stud. 2018, 37, 371–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polajnar Horvat, K.; Leban, K.; Tičar, J.; Smrekar, A. Participatory Approach to Wetland Governance: The Case of The Memorandum of Understanding of the Sečovlje Salina Nature Park. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sima, V.; Gheorghe, I. Green Customer Satisfaction. In Green Business: Concepts, Methodologies, Tools, and Applications; I. Management Association, Ed.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2019; pp. 153–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNWTO. UNWTO Website—Tourism Trends 2022. Available online: https://www.unwto-tourismacademy.ie.edu/2021/08/tourism-trends-2022 (accessed on 23 May 2023).

- Newsome, D.; Moore, S.; Dowling, R. Natural Area Tourism: Ecology, Impacts, and Management, 2nd ed.; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- López-del-Pino, F.; Grisolía, J. Pricing Beach Congestion: An analysis of the introduction of an access fee to the protected island of Lobos (Canary Islands). Tour. Econ. 2018, 24, 449–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, R. Tourism and Environment. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2011, 36, 397–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arouca Geopark. Available online: http://aroucageopark.pt/pt/conhecer/ (accessed on 26 June 2023).

- Milojković, D.; Nikolić, M.; Milojković, K. The development of countryside walking tourism in the time of the post-covid crisis. Econ. Agric. 2023, 70, 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, L. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on rural tourism: A case study from Portugal. Anatolia. An International. J. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2022, 33, 157–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polukhina, A.; Sheresheva, M.; Efremova, M.; Suranova, O.; Agalakova, O.; Antonov-Ovseenko, A. The Concept of Sustainable Rural Tourism Development in the Face of COVID-19 Crisis: Evidence from Russia. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2021, 14, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passadiços do Paiva. Website of the Paiva Walkways. (2023, July 24). Available online: http://www.passadicosdopaiva.pt/ (accessed on 2 December 2022).

- Arouca Geopark. Usos e Costumes. Available online: http://aroucageopark.pt/pt/conhecer/usos-e-costumes/ (accessed on 26 June 2023).

- Arouca Geopark. Gastronomia. Available online: http://aroucageopark.pt/pt/conhecer/gastronomia/ (accessed on 26 June 2023).

- OTSCP. Dormidas em Alojamento Turístico Continuam a Crescer no Centro, 2023. Available online: https://smat.observatorio-tcp.pt/ (accessed on 30 July 2023).

- GGN/EGN. Geopark Annual Report 2019. Available online: http://www.globalgeopark.org/UploadFiles/2020_11_3/Arouca-Geopark_UGGp_Annual_Report_2019.pdf (accessed on 26 June 2023).

- Duarte, A.%. Arouca Geopark: Um Destino Inteligente, Sustentável e Inclusivo. Available online: https://center.web.ua.pt/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/2.3.-Arouca-Destino-Inteligente-inclusivo-e-sustenta%CC%81vel-convertido.pdf (accessed on 26 June 2023).

- Rocha, D.; Belém, M.; Bastos, S.; Neves, R.; Duarte, A.; Sá, A. Paiva Walkways: A New Touristic Attraction in the Arouca UNESCO Global Geopark (Portugal). In Proceedings of the Paper presented in the 7th International Conference on UNESCO Global Geoparks, English Riviera, UK, 27 September 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Huberman, A.; Miles, M. Analyse des Données Qualitatives: Recueil de Nouvelles Méthodes, (trad. Catherine De Backer e Vivian Lamongie); De Boeck-Wesmael: Bruxelles, Belgium, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Borch, O.; Arthur, M. Strategic networks among small firms: Implications for strategy research methodology. J. Manag. Stud. 1995, 32, 419–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R. Applications of Case Study Research, 3rd ed.; Sage: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, C.B. A Case in Case Study Methodology. Field Methods 2001, 13, 329–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengtsson, M. How to perform a qualitative study using content analysis. NursinPlus Open 2016, 2, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krippendorff, K. Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology; Sage Publications Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Downe-Wambolt, B. Content analysis: Method, applications and issues. Health Care Women Int. 1992, 13, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Good Travel Guide. Arouca: Geoparque Global da UNESCO 2020. Available online: https://goodtravel.guide/portugal/arouca-green-trip/ (accessed on 26 June 2023).

- Arouca Geopark. Eventos. Available online: http://aroucageopark.pt/pt/atualidade/eventos/ (accessed on 26 June 2023).

| Items | Data |

|---|---|

| Number of employees | 15 (3 geoscientist(s)) |

| Number of Visitors | |

| Tourism Office | 4860 |

| Birthing Stones House | 32,379 |

| Meteorological Tower | 4212 |

| Trilobites Museum | 15,000 |

| Paiva Walkways | 207,192 |

| Number of Geopark events: | 100 |

| Number of school classes realize Geopark educational programs | 163 |

| Number of participants | 7188 |

| Number of Geopark press release | 65 |

| 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % Portuguese | 96.70% | 93.10% | 90.50% | 87.40% | 90.80% | 81.90% | 81.20% |

| % International | 3.30% | 6.90% | 9.50% | 12.60% | 9.20% | 18.10% | 18.80% |

| Total visitors | 192,531 | 243,139 | 199,464 | 207,192 | 105,204 | 130,194 | 300,889 |

| Media | Media Type | Documents/Pages Reviewed |

|---|---|---|

| Notícias de Aveiro | Newspaper (online) | 25 |

| Arouca Geopark | Website | 32 |

| Passadiços do Paiva | Website | 10 |

| Câmara Municipal de Arouca | Website | 6 |

| Turismo Porto e Norte | Website | 15 |

| Freguesia de Moldes | Website | 12 |

| ADRIMAG | Website | 48 |

| Scopus | Database | 12 |

| WoS | Database | 15 |

| Total | 175 | |

| Arouca Geopark Objectives | SDG Goals |

|---|---|

| Enhancing the geological heritage and the remaining natural and cultural heritage | SDG13—Take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts SDG15—Protect, restore, and promote the sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems, sustainably manage forests, combat desertification, halt and reverse land degradation, and halt biodiversity loss |

| Stimulating activities and products for a territory of science | SDG12—Ensure sustainable consumption and production patterns |

| Promote quality and contribute to the planning policies in the area of environment, agriculture, and forestry | SDG12—Ensure sustainable consumption and production patterns |

| Promote education for sustainability | SDG04—Ensure access to inclusive, quality, and equitable education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all |

| Promote a geotourism approach with particular emphasis on the qualification, organization, promotion and commercialization of its strategic tourism products | SDG8—Promote inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment, and decent work for all SDG15—Protect, restore, and promote the sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems, sustainably manage forests, combat desertification, halt and reverse land degradation and halt biodiversity loss |

| Promote a territorial dynamic, socio-cultural engagement, and strengthen the sense of belonging | SDG10—Reduce inequalities within and among countries |

| Strengthen and boost cooperation, partnerships, and networking | SDG17—Strengthen the means of implementation and revitalize the Global Partnership for Sustainable Development |

| Best Practices for Green Tourism | Best Practices for Paiva Walkways |

|---|---|

| Environmental certifications | Integrates two international certification standards: the European Charter for Sustainable Tourism, of which it has been part since 2013, and the Charter of the European and Global Geoparks Network (Good Travel Guide, 2020) Top 100 Sustainable World Destinations of 2020 (Good Travel Guide, 2020) Gold Grade sustainable destination by the Green Destinations Award program |

| Public–private partnerships | Participation in the project, Atlantic Geoparks of Interreg Atlantic Area Collaboration in the training offer on Natural Heritage of the Senior Academy of Arouca Collaboration on third Summer Training Course with UTAD (UNIVERSITY) as UNESCO Chair on Geoparks, Sustainable Regional Development and Healthy Lifestyle Managed by AGA—Arouca Geopark Association, which includes 52 effective members, 7 public and 45 private |

| Environmental awareness and education | 163 school classes with 7188 participants (GGN/EGN, 2019) Schools of Arouca as an integral member of the Destination Management Association; 5000 students participate in activities each year |

| Community involvement | Promotion of local businesses, traditions, and customs with the involvement of the whole community, namely through the organization of events with and for the community (Arouca Geopark, 2023d) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gonçalves, E.C.C.; Guerra, R.J.d.C.; Figueiredo, V.M.P.d. Green Tourism and Sustainability: The Paiva Walkways Case in the Post-Pandemic Period (Portugal). Sustainability 2023, 15, 13969. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151813969

Gonçalves ECC, Guerra RJdC, Figueiredo VMPd. Green Tourism and Sustainability: The Paiva Walkways Case in the Post-Pandemic Period (Portugal). Sustainability. 2023; 15(18):13969. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151813969

Chicago/Turabian StyleGonçalves, Eduardo Cândido Cordeiro, Ricardo Jorge da Costa Guerra, and Vítor Manuel Pinto de Figueiredo. 2023. "Green Tourism and Sustainability: The Paiva Walkways Case in the Post-Pandemic Period (Portugal)" Sustainability 15, no. 18: 13969. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151813969

APA StyleGonçalves, E. C. C., Guerra, R. J. d. C., & Figueiredo, V. M. P. d. (2023). Green Tourism and Sustainability: The Paiva Walkways Case in the Post-Pandemic Period (Portugal). Sustainability, 15(18), 13969. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151813969