Educational Accountability Policy for Sustainable Development: A Comparative Analysis across 30 Countries

Abstract

:1. Introduction

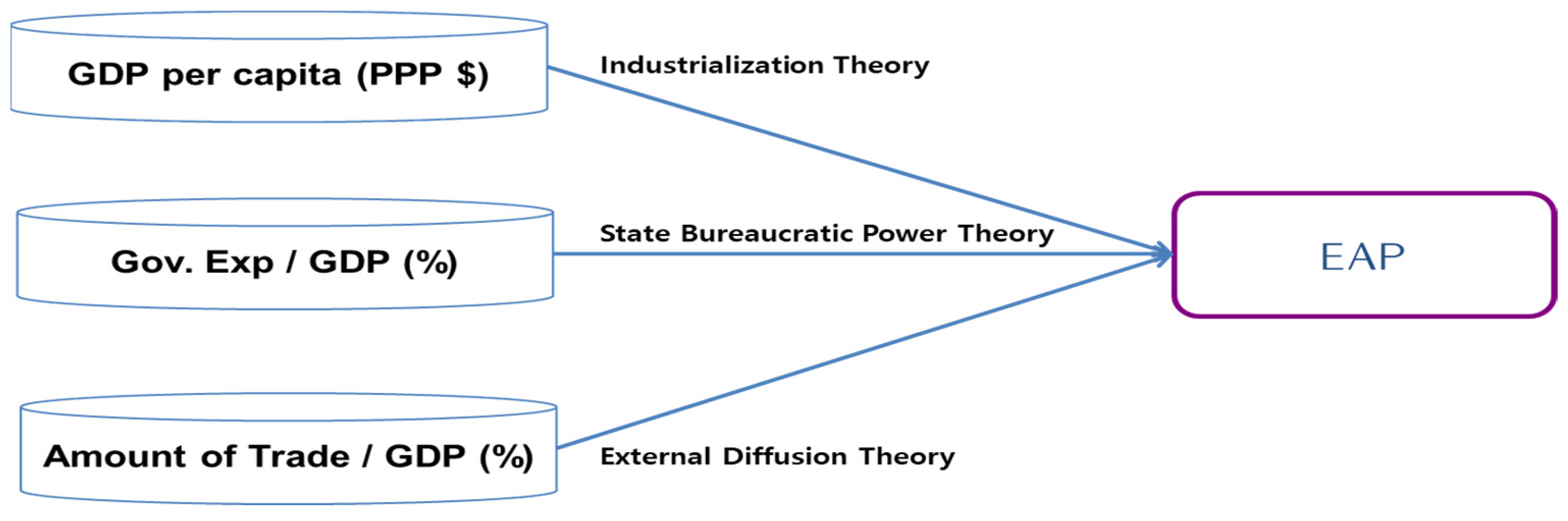

2. Theoretical Model and Research Hypotheses

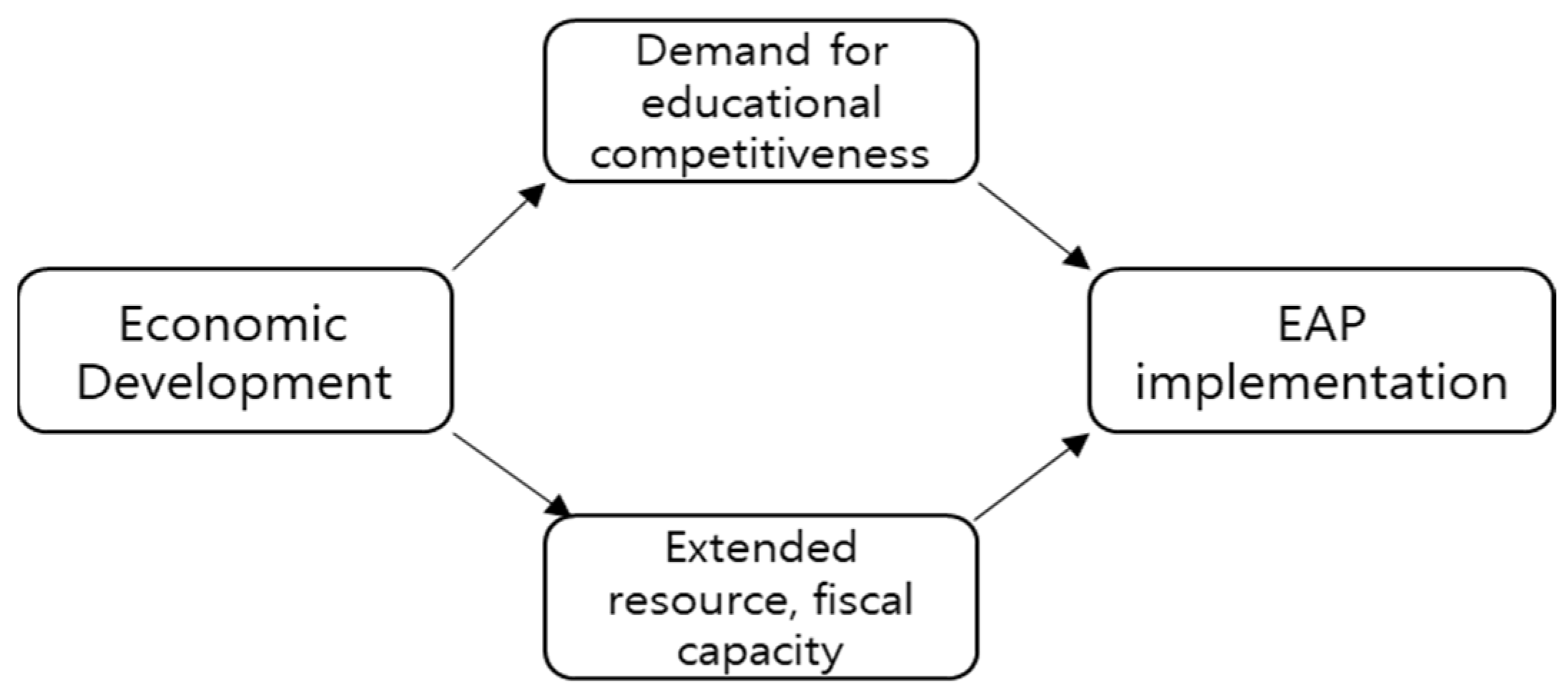

2.1. Industrialization Theory

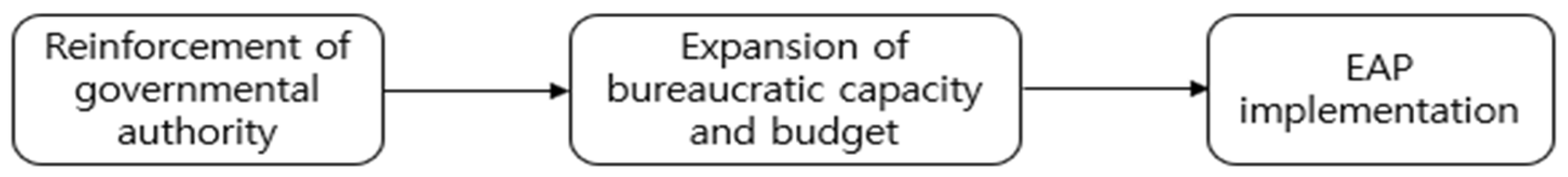

2.2. State Bureaucratic Power Theory

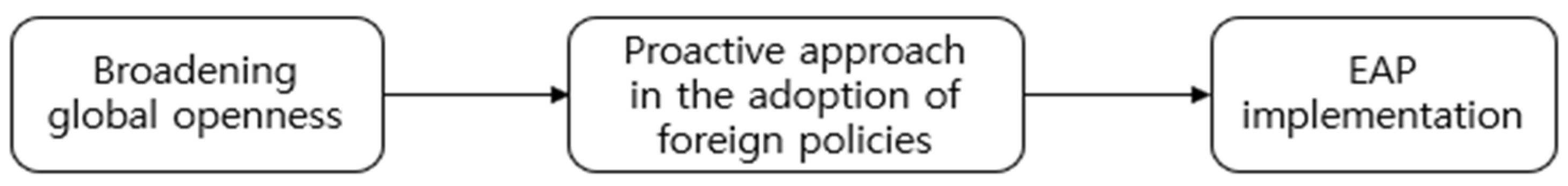

2.3. External Diffusion Theory

3. Methodology

3.1. Sample

3.2. Variables

3.3. Analytical Methods

4. Results

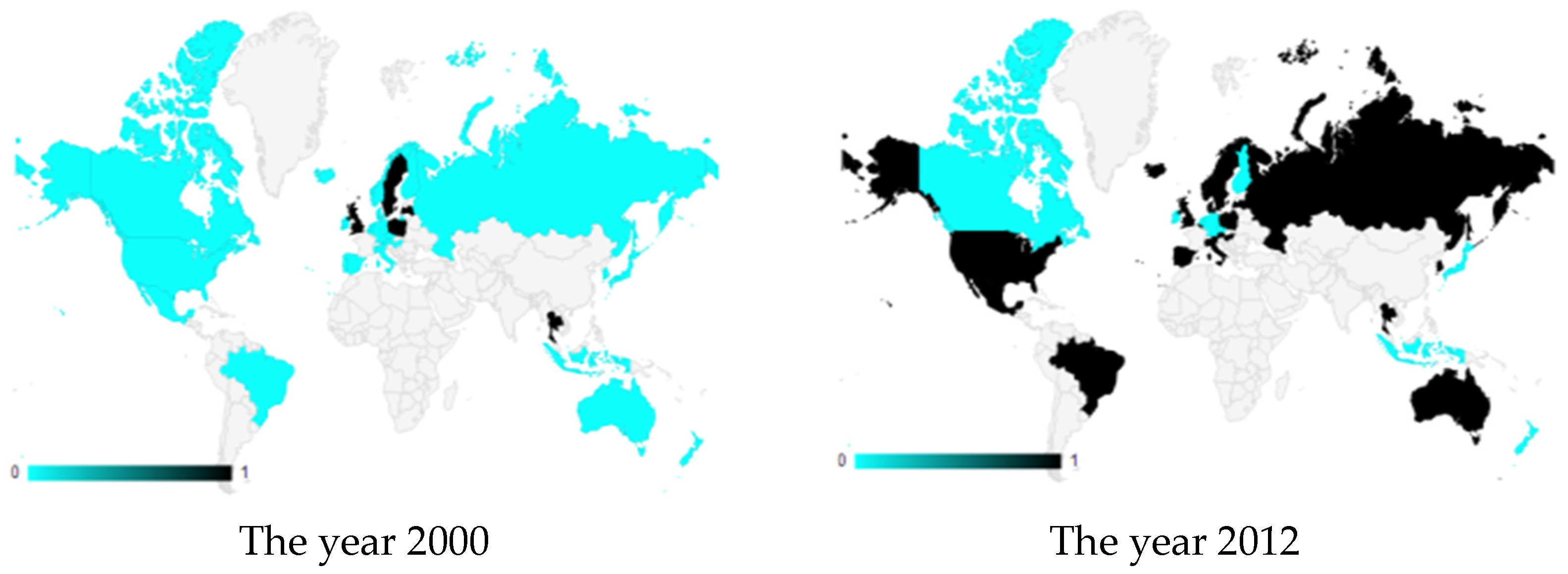

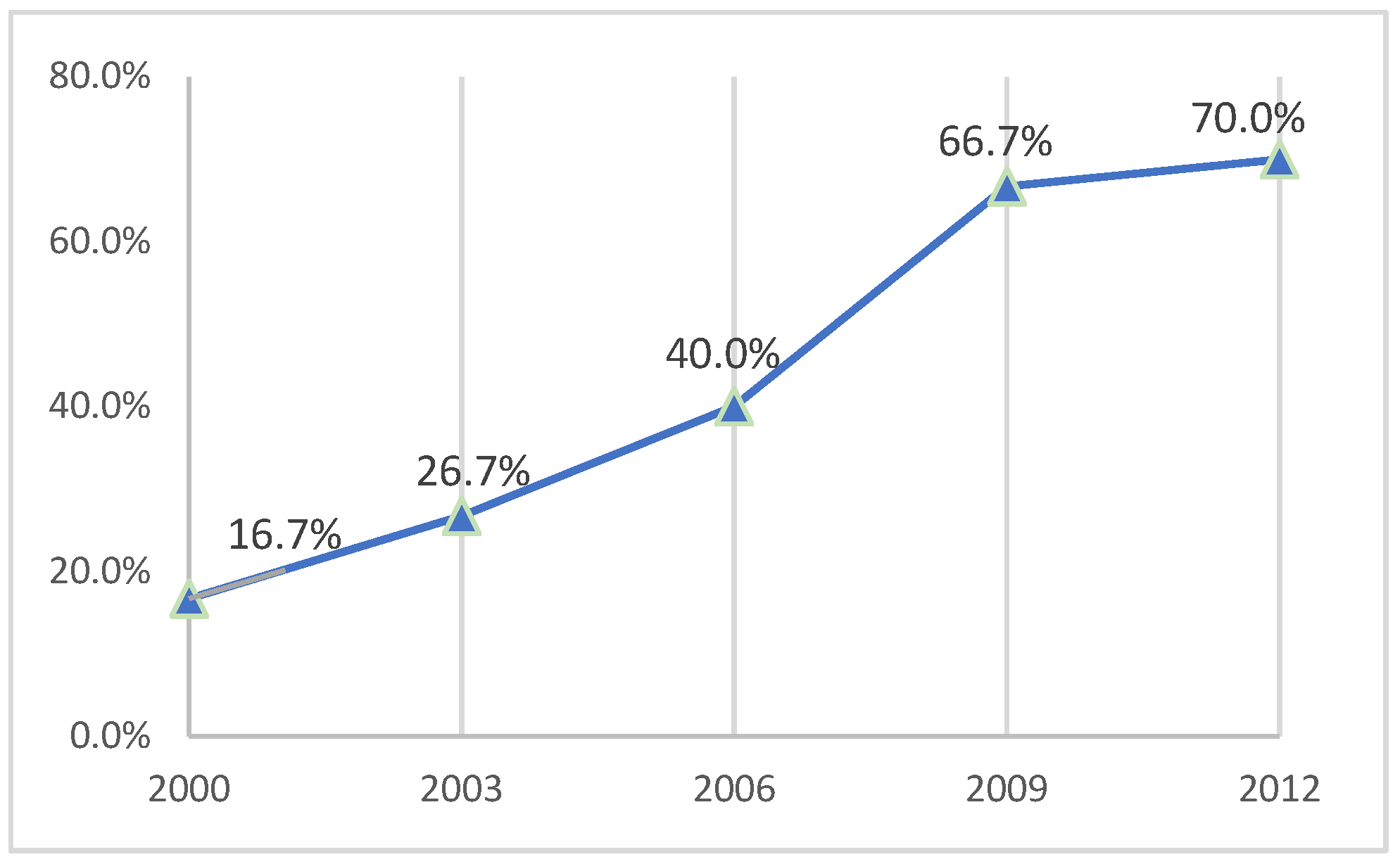

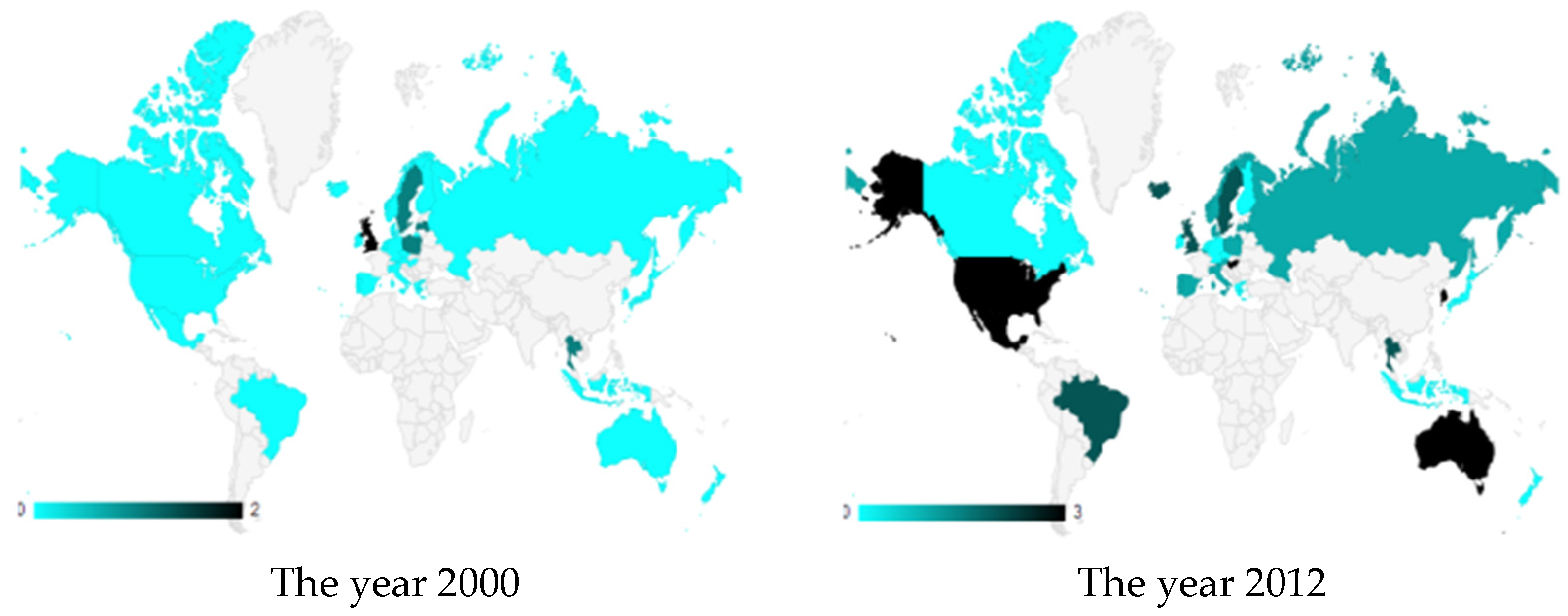

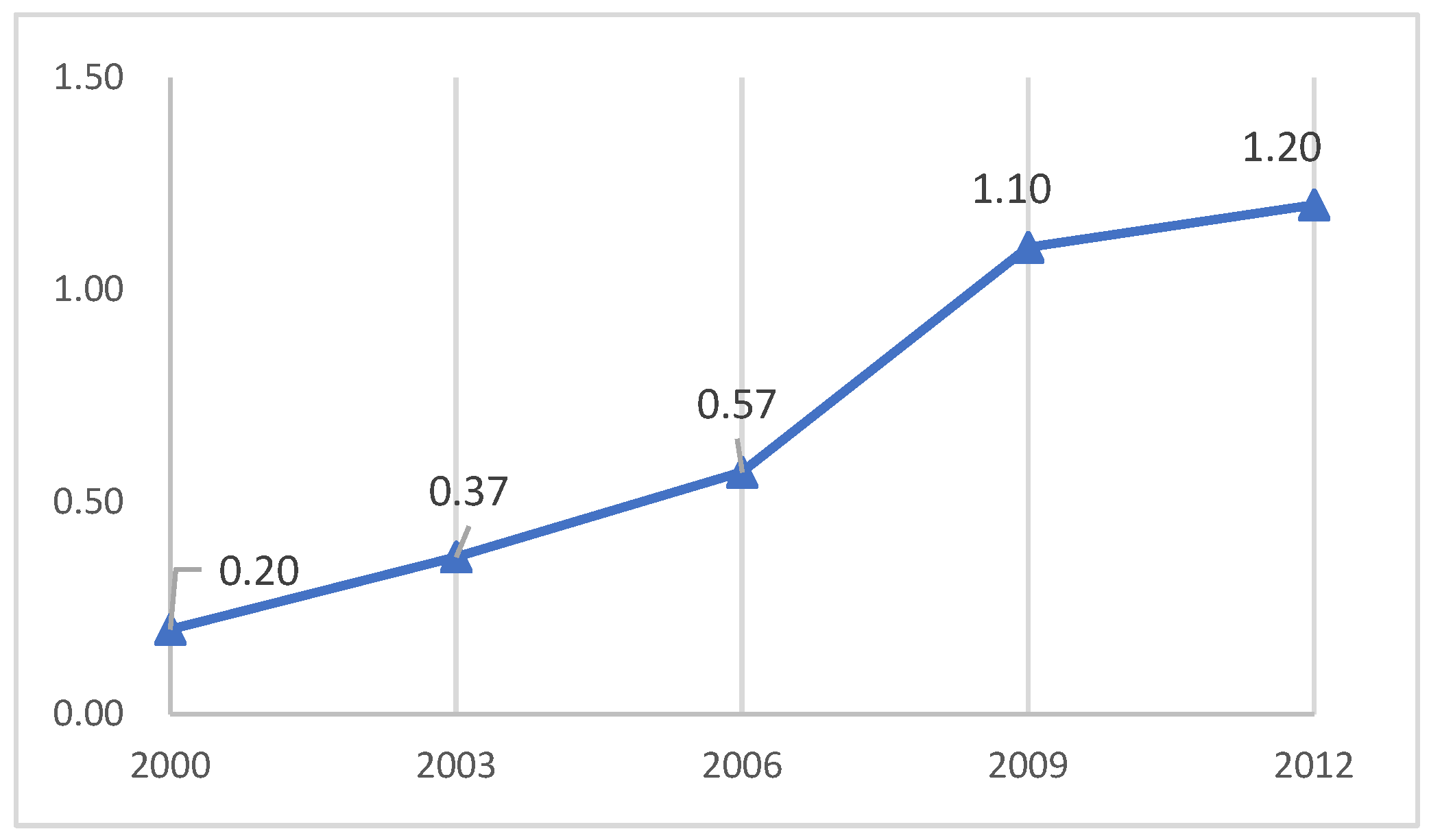

4.1. The Diffusion of EAP

4.2. The Factors Associated with the Variation of EAP across Countries

5. Discussion & Conclusions

6. Limitation and Future Research

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Barro, R.J. Education and economic growth. Ann. Econ. Financ. 2013, 14, 277–304. [Google Scholar]

- Hanushek, E.A.; Wößmann, L. Education and Economic Growth. In Economics of Education; Brewer, D.J., McEwan, P.J., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010; pp. 60–67. [Google Scholar]

- Wößmann, L.; Luedemann, E.; Schütz, G.; West, M.R. School Accountability, Autonomy, and Choice around the World; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK; Camberley, UK; Northampton, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bruns, B.; Filmer, D.; Patrinos, H.A. Making Schools Work: New Evidence on Accountability Reforms; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. The Growth Report: Strategies for Sustained Growth and Inclusive Development; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bovens, M. Analysing and Assessing Accountability: A Conceptual Framework. Eur. Law J. 2007, 13, 447–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmore, R.F. School Reform from the Inside Out: Policy, Practice and Outcomes; Harvard Education Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, J.E.; Kirst, M.W. New demands and concepts for educational accountability: Striving for results in an era of excellence. In Handbook of Research on Educational Administration, 1st ed.; Murphy, J., Louis, K.S., Eds.; Jossey-Bass Publishers: San Fransisco, CA, USA, 1999; pp. 463–489. [Google Scholar]

- Carnoy, M.; Loeb, S. Does external accountability affect student outcomes? A cross-state analysis. Educ. Eval. Policy Anal. 2002, 24, 305–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darling-Hammond, L. Standards, Accountability, and School Reform. In Facing Accountability in Education, 1st ed.; Sleeter, C.E., Ed.; Teachers College Press: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 78–111. [Google Scholar]

- Figlio, D.N.; Rouse, C.E. Do accountability and voucher threats improve low-performing schools? J. Public Econ. 2006, 90, 239–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuhrman, S.; Elmore, R.F. Redesigning Accountability Systems for Education; Teachers College Press: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Hanushek, E.A.; Raymond, M.E. Does School Accountability lead to improved Student Performance? J. Policy Anal. Manag. 2005, 24, 297–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandsma, G.J.; Adriaensen, J. The principal–agent model, accountability and democratic legitimacy. In The Principal Agent Model and the European Union, 1st ed.; Delreux, T., Adriaensen, J., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan Cham: London, UK, 2017; pp. 35–54. [Google Scholar]

- Soudry, O. A principal-agent analysis of accountability in public procurement. In Advancing Public Procurement: Practices, Innovation and Knowledge-Sharing, 1st ed.; Thai, K.V., Ed.; Academics Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2007; pp. 432–451. [Google Scholar]

- Coats, J.C. Applications of principal-agent models to government contracting and accountability decision making. Int. J. Public Adm. 2002, 25, 441–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, D.W. Analyzing the Logic and Performance of Elementary and Secondary Education Accountability Policies: A Focus on the Academic Achievement Improvement-Focused School Policy Cases. In Korean Educational Accountability Inquiry, 1st ed.; Kim, B.C., Park, N.K., Park, S.H., Byun, K.Y., Song, K.O., Jeong, D.W., Choi, J.Y., Eds.; Kyoyookbook: Paju, Republic of Korea, 2013; pp. 253–307. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, J.A. Accountability in Education; International Institute for Educational Planning: Paris, France, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Holloway, J.H. A global perspective on student accountability. Educ. Leadersh. 2003, 60, 74–76. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, H.S. An analysis of trends in school accountability. J. Educ. Adm. 2002, 20, 151–178. [Google Scholar]

- Song, K.O.; Jung, J.S. International comparative analysis of directions for educational reform. J. Educ. Adm. 2011, 29, 513–537. [Google Scholar]

- Wößmann, L. International evidence on school competition, autonomy, and accountability: A review. Peabody J. Educ. 2007, 82, 473–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, N.K. The background and context of introducing the educational accountability system. In Korean Educational Accountability Inquiry, 1st ed.; Kim, B.C., Park, N.K., Park, S.H., Byun, K.Y., Song, K.O., Jeong, D.W., Choi, J.Y., Eds.; Kyoyookbook: Paju, Republic of Korea, 2013; pp. 91–152. [Google Scholar]

- Song, K.O. Critical analysis on the primary and secondary education accountability policy in Korea. J. Yeolin Educ. 2013, 21, 207–235. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.H. A study on the nature of school accountability policy in Korea. Korea Educ. Rev. 2012, 18, 99–120. [Google Scholar]

- Gable, A.; Lingard, B. NAPLAN and the Performance Regime in Australian Schooling: A Review of the Policy Context; UQ Social Policy Unit Research Paper (No. 5); The University of Queensland: Queensland, Australia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- West, A.; Mattei, P.; Roberts, J. Accountability and sanctions in English schools. BRITISH J. Educ. Stud. 2011, 59, 41–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, F.S.; Berry, W.D. State lottery adoptions as policy innovations: An event history analysis. Am. Political Sci. Rev. 1990, 84, 395–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, F.S.; Berry, W.D. Innovation and diffusion models in policy research. In Theories of the Policy Process, 1st ed.; Sabatier, P., Ed.; Westview: Boulder, CO, USA, 1999; pp. 169–200. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson, R.E.; Robinson, J.A. Inter-party competition, economic variables, and welfare policies in the American states. J. Politics 1963, 25, 265–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toutkoushian, R.K.; Hollis, P. Using panel data to examine legislative demand for higher education. Educ. Econ. 1998, 6, 141–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boli-Bennett, J. Global integration and the universal increase of state dominance, 1910–1970. In Studies of the Modern World System, 1st ed.; Bergesen, A., Ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1980; pp. 77–107. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, J.W. The World Polity and the Authority of Nation-State. In Studies of the Modern World-System; Bergesen, A., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1980; pp. 109–138. [Google Scholar]

- Galbraith, J.K. The New Industrial State; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kerr, C. The Future of Industrial Societies: Convergence or Continuing Diversity? Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, R. Welfare and industrial man: A study of welfare in Western industrial societies in relation to a hypothesis of convergence. Sociol. Rev. 1973, 21, 535–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alber, J.; Flora, P. Modernization, democratization and the development of welfare states in Western Europe. In The Development of Welfare States in Europe and America, 1st ed.; Flora, P., Heidenheimer, A.J., Eds.; Transaction Books: New Brunswick, NJ, USA; London, UK, 1981; pp. 37–80. [Google Scholar]

- Castles, F.G. The impact of parties on public expenditure. In The Impact of Parties: Politics and Policies in Democratic Capitalist States, 1st ed.; Castles, F.G., Ed.; Sage Publications: London, UK, 1982; pp. 21–96. [Google Scholar]

- Cutright, P. Political structure, economic development, and national social security programs. Am. J. Sociol. 1965, 70, 537–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewitt, C. The effect of political democracy and social democracy on equality in industrial societies: A cross-national comparison. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1977, 42, 450–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stack, S. The effects of political participation and socialist party strength on the degree of income inequality. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1979, 44, 168–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeVINEY, S. The Political Economy of Public Pensions: A Cross-National Analysis. J. Political Mil. Sociol. 1984, 12, 295–310. [Google Scholar]

- Orloff, A.S.; Skocpol, T. Why not equal protection? Explaining the politics of public social spending in Britain, 1900–1911, and the United States, 1880s–1920. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1984, 49, 726–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, J.L. The diffusion of innovations among the American states. Am. Political Sci. Rev. 1969, 63, 880–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collier, D.; Messick, R.E. Prerequisites versus diffusion: Testing alternative explanations of social security adoption. Am. Political Sci. Rev. 1975, 69, 1299–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilcher, D.M.; Ramirez, C.J.; Swihart, J.J. Some correlates of normal pensionable age. Int. Soc. Secur. Rev. 1968, 21, 387–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taira, K.; Kilby, P. Differences in social security development in selected countries. Int. Soc. Secur. Rev. 1969, 22, 139–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargreaves, A. Teaching in the Knowledge Society: Education in the Age of Insecurity; Teachers College Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Salberg, P. Rethinking accountability in knowledge Society. J. Educ. Change 2010, 11, 45–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greiff, S.; Wüstenberg, S.; Avvisati, F. Computer-generated log-file analyses as a window into students’ minds? A showcase study based on the PISA 2012 assessment of problem solving. Comput. Educ. 2015, 91, 92–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.S.; Lee, H.J. Do school resources reduce socioeconomic achievement gap? Evidence from PISA 2015. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2022, 88, 102528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Education Week. Quality Counts (Each Year). Available online: https://www.edweek.org/leadership/quality-counts (accessed on 1 September 2023).

- Berry, F.S. Innovation in public management: The adoption of strategic planning. Public Adm. Rev. 1994, 54, 322–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kugler, J.; Organski, A.F.K.; Johnson, J.T.; Cohen, Y. Political determinants of population dynamics. Comp. Political Stud. 1983, 16, 3–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snider, L.W. Identifying the Elements of State Power Where do we Begin? Comp. Political Stud. 1987, 20, 314–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buera, F.J.; Oberfield, E. The global diffusion of idea. Econometrica 2020, 88, 83–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hage, J.; Aiken, M. Social Change in Complex Organizations; Random House: New York, NY, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Mohr, L.B. Determinants of innovation in organizations. Am. Political Sci. Rev. 1969, 63, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). PISA 2012 Results: What Makes Schools Successful? Resources, Policies and Practices; OECD: Paris, France, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, E.M. Diffusion of Innovations; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Schriewer, J.K. Globalization in education: Process and discourse. Policy Futures Educ. 2003, 1, 271–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner-Khamsi, G. (Ed.) The Global Politics of Educational Borrowing and Lending; Teachers College Press: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Takayama, K. A Nation at Risk Crosses the Pacific: Transnational Borrowing of the USA Crisis Discourse in the Debate on Education Reform in Japan. Comp. Educ. Rev. 2007, 51, 423–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). Who Cares about Using Education Research in Policy and Practice? OECD: Paris, France, 2022. [Google Scholar]

| 2000 | 2003 | 2006 | 2009 | 2012 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Australia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 |

| Austria | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Belgium | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Brazil | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Canada | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Czech Rep. | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Denmark | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Finland | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Germany | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Hong Kong | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Hungary | 0 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 |

| Iceland | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Indonesia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Ireland | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Italy | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Japan | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| South Korea | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 |

| Latvia | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Mexico | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 3 |

| Netherlands | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| New Zealand | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Norway | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Poland | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Portugal | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Russia | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Spain | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Sweden | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Thailand | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| UK | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| USA | 0 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Variable | Description | Mean | Std. Dev. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variables | EAP index score | 3: 3 components of EAP are all implemented 2: 2 components of EAP are implemented 1: 1 component of EAP is implemented 0: no component implemented | 0.689 | 0.924 |

| EAP implementation | 1: 1 or more components of EAP implemented 0: no component implemented | 0.440 | - | |

| Independent variables | GDP per capita | Real GDP (PPP) per capita (in US $) | 27,567.280 | 12,284.420 |

| State Bureaucratic Power | The ratio of government expenditure to GDP (%) | 40.223 | 10.841 | |

| Degree of openness | The ratio of trade volume to GDP (%) | 47.304 | 34.412 | |

| PISA Score | Average PISA score of reading, math, and science by countries | 491.809 | 41.431 | |

| Population | total population (in million) | 54.909 | 72.936 | |

| Pooled Logit Model | Panel Random Effect Logit Model | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. (B) | Std. Error | Exp (B) | Coef. (B) | Std. Error | Exp (B) | |

| GDP per capita | 0.029 | (0.020) | 1.030 | 0.691 *** | (0.211) | 1.995 |

| State Bureaucratic Power | 0.015 | (0.020) | 1.015 | 0.395 ** | (0.180) | 1.484 |

| Degree of openness | 0.011 * | (0.006) | 1.011 | 0.060 | (0.068) | 1.062 |

| PISA Score | −0.012 ** | (0.006) | 0.988 | −0.019 | (0.057) | 0.981 |

| Ln (Population) | 0.218 | (0.145) | 1.244 | 4.011 * | (2.355) | 55.189 |

| (LR/Wald) | 9.48 * | 20.95 *** | ||||

| Obs. | 148 | 148 | ||||

| Test for setting random effect | χ2(1) = 60.16 *** | |||||

| Pooled Ordered Logit Model | Panel Random Effect Ordered Logit Model | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. (B) | Std. Error | Exp (B) | Coef. (B) | Std. Error | Exp (B) | |

| GDP per capita | 0.042 ** | (0.018) | 1.043 | 0.227 *** | (0.044) | 1.255 |

| State Bureaucratic Power | 0.007 | (0.019) | 1.007 | 0.119 *** | (0.041) | 1.126 |

| Degree of openness | 0.006 | (0.006) | 1.006 | 0.030 *** | (0.011) | 1.031 |

| PISA Score | −0.013 ** | (0.006) | 0.987 | −0.042 *** | (0.011) | 0.959 |

| Ln (Population) | 0.288 ** | (0.146) | 1.334 | 1.905 *** | (0.430) | 6.722 |

| (LR/Wald) | 19.36 *** | 46.47 *** | ||||

| Obs. | 148 | 148 | ||||

| Test for setting random effect | var (panel) = 36.59 ** | |||||

| Economic Development | Government Bureaucratic Power | Degree of Openness | Average PISA Score | Population | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EAP implementation | + | + | . | . | + |

| EAP implementation intensity | + | + | + | + | + |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, Y. Educational Accountability Policy for Sustainable Development: A Comparative Analysis across 30 Countries. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13883. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151813883

Kim Y. Educational Accountability Policy for Sustainable Development: A Comparative Analysis across 30 Countries. Sustainability. 2023; 15(18):13883. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151813883

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Youngsik. 2023. "Educational Accountability Policy for Sustainable Development: A Comparative Analysis across 30 Countries" Sustainability 15, no. 18: 13883. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151813883

APA StyleKim, Y. (2023). Educational Accountability Policy for Sustainable Development: A Comparative Analysis across 30 Countries. Sustainability, 15(18), 13883. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151813883