Abstract

We explore the importance of climate change as a news topic and examine the relationship between climate change news and financial returns using a large news database that consists of more than 4 million news stories. We use multinomial inverse regression—a Bayesian approach capable of handling the multi-dimensionality of our data—to translate news into a quantifiable input. We also build a climate change dictionary from different sources to identify climate change related words. We find that climate change is a persistent topic in our news universe, which indicates that it is a relevant news topic. This relevance is supported by the non-zero contribution of climate change related trigrams (CCRTs) in the constructed news index. However, our sample does not show an increasing trend of the relative daily presence of CCRTs, which signals that the news are unlikely the source that furthers the perceived increasing awareness of climate change. Lastly, we determine the salient CCRTs present during good and bad days of the market. This result highlights the presence in the news of topics related to fuel and energy, emission, climate change, disaster, and fiscal policy.

1. Introduction

The potential devastating effects of climate change pose a problem to sustainability and to the world’s economic growth based on fossil energies that result in costs to the society. As such, climate change has been a concern to different sectors, including finance, and has been drawing media attention, resulting in more and accessible climate change information.

The majority of climate change experts advocate limiting emissions to 2 °C above the average temperature of pre-industrial times. This challenge to the world’s economy is somehow two-fold as delaying action is costly but the investments needed for the transition to new energies sources are significant. Examples emphasizing the economic consequences of inaction are Stern [1], who estimates the overall annual cost of a 5 °C increase in temperature to be 5% of the global domestic product, and a meta-analysis by Furman et al. [2] that demonstrates delaying policies pointed to hit a specific temperature target results in a 40% increase in overall costs. The transition to a low-carbon economy cannot be taken for granted. On the one hand, the global agreements such as Copenhagen or Paris do not set binding targets [3], impeding global coordination of efforts. On the other hand, uncertainty about the costs and how climate change will unfold is high [4] leaving room for different interpretations of climate change threats.

Unanimous or not, the transition to alternative sources of energy is on its way, is expensive, and requires funding. In this context, Boissinot et al. [5] discuss costs and possible sources of financing for this energy transition and argue that, even if the financing costs are large, they are still feasible if climate policies are correctly designed to facilitate the global financial system’s role as capital reallocator. Moreover, papers such as Kaminker and Stewart [6], Johnson [7], Grundl et al. [8], and Ameli et al. [9] go a step further by highlighting the potential role of private funds, in particular managed by institutional investors, in various types of investment activities and instruments linked to decarbonization and climate change risk management. The role of investors in climate change mitigation is also discussed in papers such as MacLeod and Park [10], which studies how activist investors influence decision making in fossil fuel companies or papers by Ansar et al. [11] and Ayling and Gunningham [12], which analyze the divestment movement, the concept of stranded assets, and the risks they pose to fossil fuel companies.

Although, as proposed by Hong and Scheinkman [13], it can be argued that asset pricing researchers arrived late to the climate change discussion, the basic theoretical argument underlying the papers relating energy transition and investor’s decision making can be argued to be as old as finance itself. In effect, these papers build on the efficient market hypothesis [14] to argue that investors’ attitudes towards green investments vehicles, companies, assets, or infrastructures should respond to climate change related information, thus impacting financial returns. Among many recent papers studying the relationship between climate change and financial returns, Antoniuk and Leirvik [15] show that global events that increase climate change awareness result in positive abnormal returns for green stocks while the ones that deteriorate the climate change policy are beneficial for brown ones. Hong et al. [16] provide evidence that food stock prices under-react to climate change risk while Choi et al. [17] pose that attention to climate change increases during periods of unusually warm temperatures so that during these times carbon-intensive emission firms perform worse than low carbon emission ones. A similar point is supported by Giansante et al. [18] who find that firm’s future emissions affect the returns negatively. On whether climate change risk is being considered by investors, Huyn and Xia [19] show that investors have a preference for corporate bonds that potentially serve as climate change risk hedges (for a comprehensive review of asset pricing literature considering climate change as an additional source of risk in the stock market, see Ref. [20]). Being a special case of the literature studying the news—returns relationship, the climate change news—returns relationship literature suffers from the same limitations. In particular, most of the papers deal with a small set of events, provide evidence on small samples of financial instruments, and do not control for the news universe available at the moment of the investor’s decision making.

A recent paper by Ferrer et al. [21] builds a news index based on the multinomial inverse regression [22] and textual analysis by using more than 4 million news stories gathered from Thomsom Reuters online archive. This news index is comprehensive in that it takes into account the whole universe of news and has explanatory power over stocks, bonds of different qualities, and commodity indexes. Moreover, it is granular in that it attaches a coefficient to each of the trigrams extracted from the news, providing information on the relative importance of each of them in the available universe of aggregated daily news. In this paper we propose to capitalize on the granularity provided by the methodology in building the index and analyze the role of climate change related trigrams (CCRTs) in financial returns. Our research question is the relationship between climate change news content and the returns of various financial instruments. To address it we first provide a description of the amount of climate change trigrams in the universe of news and of their relative importance in the overall news index. Then, we study how the appearance of these trigrams contributes to the dynamics of financial indexes related to stocks, bonds, and commodities. We believe that this paper contributes to the literature in several ways. First, the size of the news database allows us to consider climate change in a setting in which it competes for investors’ attention with many other subjects. Second, the methodology we propose allows us to provide insights about the relative importance of climate change in the quantitative news index. Lastly, our methodology also allows us to identify salient CCRTs on days when the market is performing good or bad and to relate them to the risk characteristics of the various financial indexes.

2. Materials and Methods

In this paper we construct the index proposed by Taddy and developed by Ferrer et al. [21] using 4,015,564 online news stories in English aggregated daily. These news stories were collected from the Reuters news archive and cover the period from the 1st of February 2007 to the 17th of September 2018, which is the last day when the news archive was publicly available. To understand the role of climate change in financial returns, we propose analyzing the dynamics of the CCRTs’ relative presence in the news universe and constructing quintiles of news trigrams to determine the weight of CCRTs in each. We also intend to examine which are the CCRTs that are associated with bad and good days of the financial markets.

Because different financial markets are diverse in nature and their individual performance can be calculated through several measures, we include eight financial indexes associated to markets carrying different risk profiles and financial instruments: (i) four equity indexes, the Standard and Poors 500 (SP500), the Dow Jones Sustainability Index (DJSI), the Fama and French’s Market Factor (MKT), and the Wilshire 5000 Total Market Index (W5000); (ii) three bonds indexes, the ICE BofA U.S. Corporate Index (CInvGrade), the ICE BofA U.S. High Yield Index (CHighYield), and the ICE BofA U.S. Corporate Index & High Yield Index (CTotal); and (iii) one commodity index, the Refinitiv Core Commodity Index (CC-CRB). This diverse group of indexes covers instruments in main financial markets. Including different indexes for the same markets allows us to control for different performance measures in the case of the stocks and for different quality of the instruments in the case of bonds. In the same vein, the commodity index we chose is broad and related to the behavior of core commodities.

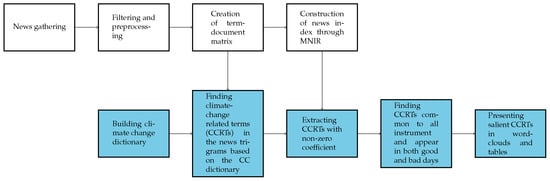

The flowchart of our study is presented in Figure 1, which depicts the processes necessary for the construction of the index (white rectangles), for the analysis of the climate change news, expected returns relationship (cyan rectangles), and how they are related. Each of the steps that constitute these processes is described throughout the remainder of this section.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the present study. This figure shows the flowchart describing the processes necessary to our study. The rectangles in white represent the steps necessary to the construction of the news index. The ones in cyan are the steps leading to the analysis of the climate change news content—financial returns relationship. Arrows uniting a white rectangle with a cyan one represent that information from the first is necessary for the second one.

2.1. Building a Comprehensive and Granular News Index through a Multinomial Inverse Regression

In text mining and text analysis studies, the primary challenges are the conversion of the text data into a numerical input that is possible to analyze quantitatively and addressing the curse of high dimensionality. Given the size of our news sample the problem of high dimensionality is evident. To tackle this issue we propose to follow the multinomial inverse regression (MNIR) method by Taddy [22], which enables us to construct a news index of the 4 million news we deal with in this paper. This method allows for the calculation of a sufficient reduction score, which we refer to as news index, which preserves information relevant to the variable being associated to the text, which in this case are the returns.

Our methodology involves transforming the news data into a corpus and undergoing preprocessing in order to standardize the words in the entire set of documents, which helps in reducing the dimensionality. In the preprocesing, we transform all words to lowercase, stem or reduce words to their root word (for example, talked and talking will be both reduced to talk), and we remove very common words usually referred to as stopwords such as the articles, conjunctions, and forms of the verb “to be”. Aside from these words, we also exclude punctuation marks and other characters that are not relevant in the analysis. Then, we tokenize the words into 3-word tokens or trigrams and represent them into a term-document matrix (TDM). This matrix is a tally of the presence of each term in each document, which is composed of all the news in each day and is the primary input in the MNIR. Each document of aggregated daily news is treated as a collection of exchangeable tokens, implying that the sequence of tokens can be neglected. To further reduce the dimensionality, we remove less frequent words in the TDM following similar studies. In particular we remove the bottom 1% of all the words in terms of frequencies.

We further explain the MNIR below using the same notation as Taddy [22] to maintain consistency. Each document of aggregated daily news i is expressed as , which is a vector of counts for each of the p tokens in the dictionary. From these token counts, empirical frequencies are calculated using the equation where is the total number of counts of each token in document i. Token counts and the associated frequencies form the basic data units for the MNIR, which is expressed as:

where is a p-dimensional multinomial distribution with size and probabilities Based on the conditions detailed in Taddy [22], the sufficient reduction (SR) score for is equal to the inner product of the MNIR regression coefficients or factor loadings and the empirical frequencies . Mathematically, the sufficient reduction (SR) score is written as:

Equation (2) implies that is a sufficient statistic for because the outcome variables are considered independent of the text counts conditioned on the projection [23]. This SR score can be interpreted as the average factor loading or contribution of document i [24], a variable similar to the Altman’s z score, which indicates the credit quality of a company [25]. Using Equation (1), the factor loading can be estimated using fat-tailed and sparsity-inducing independent Laplace priors for each coefficient [22]. In this study, the coefficient or factor loading of each trigram provides the identification of the relative importance of the specific element in the news to the news index and is of our particular interest.

2.2. Establishing the Role of Climate Change News in the Market

To establish the relationship between climate change and the financial returns of the market, we first need to identify the CCRTs present in the news. To determine which trigrams should be classified as CCRTs, we build a climate change vocabulary from three sources. Namely, (i) Dictionary of climate change and the environment: Economics, science and policy [26], (ii) Climate Change Glossary from the United States Forest Service [27], and (iii) Glossary of the IPCC 2018 [28]. All the entries in these three sources are combined excluding acronyms that are not directly related to climate change and words that are too common. We process these sources in the way we treat the news corpus. Next, we match the presence of each CCRT in the final climate change vocabulary in the final term-document matrix.

We determine the relative presence of CCRTs by looking at the evolution of their presence in our universe of news. After this, we look at the relative importance in terms of their intensity or contribution to the index. We do this by identifying CCRTs’ proportion to the trigrams in each quintile based on coefficients in the overall news trigrams. Finally, we present the most salient CCRTs on good days or bad days through word clouds.

3. Results

Table 1 provides information about the relative importance, in terms of presence, of climate change content in our news sample. In particular, it shows that out of 62,939 news trigrams, there are 2195 CCRTs (3.49%) and 60,744 (96.51%) non-CCRTs. It is important to note that we cannot infer whether this overall proportion is relatively low or high compared to any other theme present in the news because classifying all other trigrams in themes is out of the scope of this paper. However, Table 1 supports that CCRTs are not only present in our sample but, more importantly, have sufficient presence to survive the preprocessing where trigrams that appear sporadically are eliminated. Moreover, the CCRTs are consistent with the rest of the trigams in terms of mean and standard deviation.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of the coefficients of all trigrams, non-CCRTs, and CCRTs. This table presents the descriptive statististics of all (All), non-climate change (Non-CCRTs), and climate change (CCRTs) related trigrams.

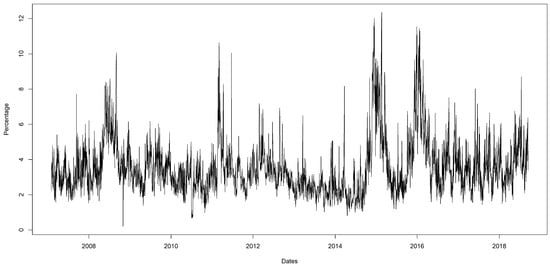

Moving to the evolution of presence over the years, Figure 2 depicts a volatile CCRTs presence that, nonetheless, does not show an increasing trend. Although we can observe some periods during which the relative presence of CCRTs is higher, the relative daily presence of CCRTs reverts to the mean proportion of 3.53% showing that climate change is a subject that keeps its relevance all along the observation period.

Figure 2.

Daily proportion of climate change and non-climate change trigrams in the news. This figure shows the daily proportion of CCRTs and non-CCRTs with non-zero coefficients over the total number of news trigrams with non-zero coefficients.

To provide further insights into the role played by CCRTs, we present the relative importance of CCRTs in terms of intensity by looking at their coefficients or factor loadings, which represent their contribution to the overall news index. As seen in Table 1 the minimum and the maximum values of the coefficients of CCRTs are lower in magnitude than the non-CCRTs, indicating that CCRTs do not appear in the extremes of the general distribution. In addition, the mean of the CCRTs is about twice as negative as the mean of non-CCRTs. Overall, the results suggest that by considering the extreme values in the general distribution, CCRTs are equally important as non-CCRTs or may even have higher importance in terms of intensity. This interpretation is also supported by Table 2, which exhibits the distribution of non-CCRTs and CCRTs by quintiles. Q1 includes the trigrams with lowest coefficients while Q5 includes the trigrams with highest coefficients. In Q1, the minimum coefficient of non-CCRTs is much more negative than the minimum of CCRTs but the maximum is basically the same. In Q5, the maximum coefficient of non-CCRTs is much more positive than the maximum of CCRTs but the minimum is basically the same. The minimum and maximum coefficients in Q2, Q3, and Q4 are almost the same. This confirms that, excluding the trigrams with extreme loadings, CCRTs are equally important as non-CCRTs. On the other hand, the last column in Table 2 shows that the percentage of CCRTs over all the news trigrams ranges from 3.15% to 3.89%, indicating that there is no quintile where CCRTs are particularly concentrated as they are almost uniformly distributed across quintiles of all news trigrams.

Table 2.

Distribution of climate change trigrams in the quintiles of overall news trigrams. This table presents the minimum and the maximum coefficients of climate change-related trigrams (CCRTs) and non-climate change related trigrams (non-CCRTs) in every quintile. Q1 contains the lowest coefficients while Q5 refers to the highest coefficients. The last column shows the percentage of climate change trigrams over all the news trigrams in each quintile.

The final set of results involves the relationship between climate change content of news and financial returns. To present them, we separate good (Q5) and bad (Q1) days according to daily returns and compare the trigrams that are present in each group. The first result to be observed is that the trigrams in the universe of all news is basically the same in every quintile of returns. The same can be observed in the CCRTs universe. This indicates that news writers cover certain subjects, including climate change, on a regular basis. This regularity, which we discuss in the succeeding paragraphs, is captured by our methodology. Note that there may be outlier subjects on certain days, but these would be screened-out in our preprocessing steps.

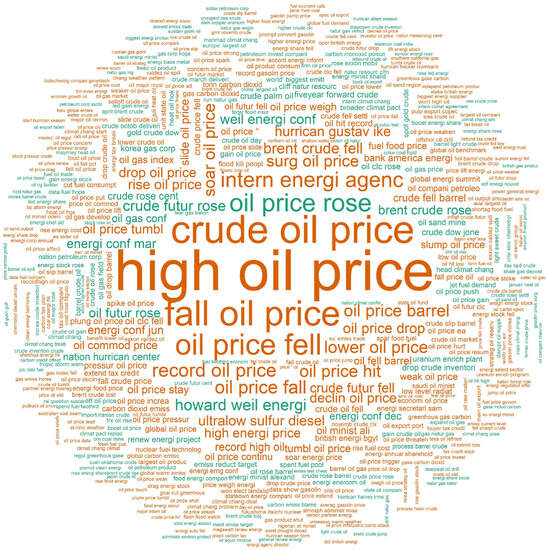

A relevant point to raise is that, even if the universe of CCRTs is the same on good and bad days, the frequency of appearance for each one is not. Therefore, it is not the specific CCRT but its frequency of appearance that is informative about financial returns. In this sense, although we cannot compare particular trigrams appearing in good versus bad days, we can analyze the differential frequencies. To illustrate which are the subjects that news writers report on a regular basis we look at the differential frequencies of CCRTs common to all the financial indexes and that appear in both good and bad days, and represent them in Figure 3. A positive difference is represented by green colored trigrams in the figure and indicates that the CCRT appears more frequently on good days. In turn, a negative difference is represented by red colored trigrams and implies that the CCRT appears more frequently on bad days. Table A1 in the Appendix A presents the top ten percent CCRTs common to all financial indexes that appear in both good and bad days of the market and their coefficients.

Figure 3.

Word cloud of common climate change trigrams between good and bad days. This word cloud shows the common climate change trigrams in good days (Q5) of all the financial instruments that are also present in the common climate change trigrams in bad days (Q1) of all the financial instruments. The size of the trigram is proportional to the absolute value of the difference between the trigram frequency in the two states. Green trigrams are the ones with positive differences, which indicate they appear more frequently on good days than on bad days. Red trigrams are the ones with negative differences, which indicate that they appear more frequently on bad days than on good days.

The figure reveals that topics related to fuel such as “high oil price”, “crude oil price”, “fall oil price”, “oil price fell”, and “oil price rose” dominate most salient common CCRTs. This is not surprising given the contribution of the energy sector and the fossil energies to climate change due to their role in economic activities involving the production and transport of goods and people. These trigrams are about price action and are very frequent in both good and bad days. We notice, however, that CCRTs that are more frequent in good days tend to have positive coefficients and relate more to the increase in fuel price.

One may argue that fuel and energy trigrams are expected to always be in the news and the news about them may not necessarily be related to climate change. This may cast doubt on the importance of climate change in the news. The presence of non-fuel and non-energy related CCRTs in the most salient common CCRTs, however, supports the belief that climate change is important. We classify these trigrams into different categories in Table 3. We find trigrams about carbon and emission such as “carbon dioxid emiss”, “emiss reduct target”, and “gas carbon dioxid”. Interestingly, most of them appear more frequently on bad days and carry negative coefficients. Disaster is another theme of the most salient CCRTs. Under this category, disaster-specific CCRTs such as “exxon valdez spill”, “flood kill peopl”, and “hurrican gustav ike” are more frequent on bad days than on good days and have negative coefficients. Albeit very few, fiscal policy related CCRTs also appear in the list. Among them are “energi tax break”, and “tax oil compani”, which appear more frequently on bad days and have negative coefficients. The last group is formed by trigrams including the term “climat chang”. These have more presence on good days and tend to have positive coefficients.

Table 3.

Most salient non-fuel and non-energy related CCRTs. This table presents non-fuel and non-energy climate change related trigrams (CCRTs) classified into several categories. Green trigrams are the ones with positive differences, which indicate that they appear more frequently on good days than on bad days. Red trigrams are the ones with negative differences, which indicate they appear more frequently on bad days than on good days.

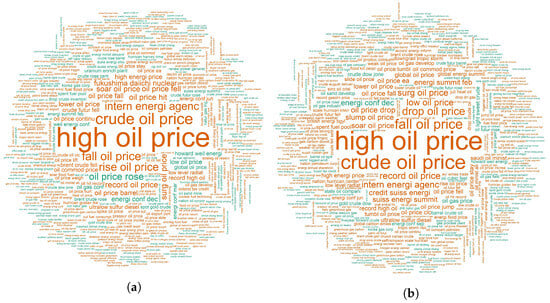

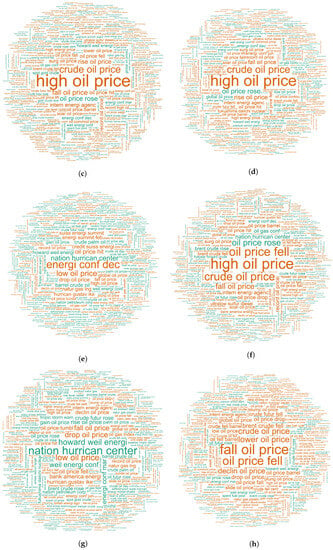

The particularities in differential frequencies related to each of the financial instruments are depicted in the form of word clouds in Figure 4. On the one hand, the word clouds are similar in terms of the most salient topics, suggesting that the effect of CCRTs in equity, bond, and commodities is related to similar subjects.

Figure 4.

Common climate change trigrams on good and on bad days. Each sub-figure shows the common climate change trigrams during good and bad days for each financial instrument; (a) relates to the Standard and Poors 500 (SP500), (b) to the Dow Jones Sustainability Index (DJSI), (c) to the Fama and French’s Market Factor (MKT), (d) to the Wilshire 5000 Total Market Index (W5000), (e) to the ICE BofA U.S. Corporate Index (CInvGrade), (f) to the ICE BofA U.S. High Yield Index (CHighYield), (g) to the ICE BofA U.S. Corporate Index & High Yield Index (CTotal), and (h) to the Refinitiv Core Commodity Index (CC.CRB). The size of the trigram is proportional to the absolute value of the difference between the trigram frequency on good days (Q5) and on bad days (Q1). Green trigrams are the ones with positive differences, which indicate that they appear more frequently on good days than on bad days. Red trigrams are the ones with negative differences, which indicate that they appear more frequently on bad days than on good days.

On the other hand, the CCRT word clouds of stock indexes (SP500, DJSI, MKT, W5000) look the same and the most salient topic pertains to oil and energy. The most salient topics in the bond indexes also include oil and energy but disaster emerges as a topic. Although there is some similarity in terms of CCRTs per se, each of these bond indexes word clouds differ in which CCRTs they highlight on bad or good days. The word cloud of high yield bond index (CHighYield) has more similarity to the word clouds of the stock indexes. Finally, in the word cloud of the commodity index CC.CRB, we see that oil is the salient topic for this index. However, CCRTs relating to the decline of prices appear more frequent on bad days, contrary to what is observed in the stocks indexes where CCRTs relating to the rise of prices are more frequent on bad days than on good days.

To help with the identification of the trigrams that mostly affect each of the financial markets proposed in this study, Table 4 lists the most salient climate change related trigrams on good and on bad days by market. This differentiation by market shows patterns that are worth to notice. In the case of the stock markets, all except for one trigram is more common during bad days. The particular trigram appearing more often during good days is “oil price rose”. We will provide an interpretation of this result in Section 4. In terms of commodities, none of the most salient CCRTs are more frequent during good days. Finally, only in the case of bond markets more than one of the CCRTs appear more often on good days.

Table 4.

Most salient climate change related trigrams on good and on bad days by financial markets. This table presents the top 10 CCRTs with the greatest absolute difference between good (Q5) and bad (Q1) days for each of the 8 financial instruments chosen in this study. Green trigrams are the ones with positive differences, which indicate that they appear more frequently on good days than on bad days. Red trigrams are the ones with negative differences, which indicate they appear more frequently on bad days than on good days.

4. Discussion and Practical Implications

The results presented in this article demonstrate that the news content related to climate change is extensive and consistent. The persistent presence of CCRTs in a mainstream publication such as Reuters contradicts the idea that climate change is not a relevant enough topic.

Moreover, the distribution of the coefficients of CCRTs and non-CCRTs suggests that climate change news content generates market movement but does not drive the extreme values of the news index. The fact that 1233 out of the 2185 CCRTs common to the financial markets we studied are more frequent on bad days indicates that financial markets consider climate change a negative issue. In addition, although papers such as Refs. [17,29,30,31,32] argue that investor attention or awareness of climate change has increased over time, the lack of an increasing trend in CCRT participation in the news universe of our database suggests that the source of this growing awareness is unlikely to be articulated through the news. Therefore, the first practical implication for agents interested in disseminating content related to climate change is to consider different sources of transmission.

Another significant result is the relevance of the “carbon and emission” theme among CCRTs. Indeed, that most of them appear more frequently on bad days and carry negative coefficients may indicate that the market recognizes the negative consequence of greenhouse gas emissions. This negative reaction from the market should put pressure on firms, especially the carbon-intensive ones, to reduce emissions as part of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) practices [33,34]. In addition, we believe that this result highlights the transport sector, in particular the road transport, as a main driver of risk for sustainability and human health in the form of air pollution [35,36]. The fact that the market seems to understand its negative effects should facilitate the adoption of cleaner transport solutions, being an incentive for governments to support green transport development.

Finally, we believe the patterns observed in word clouds for different financial markets reveals the robustness of our results. Indeed, the results seem to be consistent in terms of differentiating markets according to their risk profiles. In this context, the word clouds of stock indexes are almost indistinguishable, showing that the effects of CCRTs on these markets are observed despite the use of different indexes. In addition, the word clouds associated to speculative bonds (high yield ones) is more similar to the ones of the stock market than to the one for high quality bonds. One possible explanation for this result is that while fixed income assets have lesser risk than stocks [37], CHighYield consists of below investment grade rated bonds. These bonds are the riskiest and most likely have similar risk as the stock indexes. In addition, while stock and bond returns have a positive correlation, commodities are considered to have negative correlation with stocks and bonds [38,39,40]. Our results reflect this stylized fact on commodities.

5. Conclusions

The impact of climate change news on financial returns remains a subject of ongoing debate. In this study, we address the question at hand by exploring the relationship between climate change and financial returns. We use a novel methodology capable of handling high-dimensional data, multinomial inverse regression, to translate news information into a quantitative news index. Next, we identify the importance of climate change in terms of relative presence and intensity or contribution to the news index. We discovered that climate change is continuously and persistently present in our information universe. Our results also shed some light on the belief that climate change awareness has been increasing given the major climate change events in the past decade. We cannot argue whether this is true or not. What our results show is that if this is the case, the increase in climate change awareness is more likely to come from other sources than from the news because there is no increasing trend in the daily relative presence of CCRTs in our news universe. Finally, this study reveals certain climate change topics that stand out during good and bad market days, such as fuel and power, emissions, climate change, disasters, and fiscal policy.

Although these topics are related to the fundamental aspects of sustainability, the limitations of the study prevent us from delving into important aspects both for subsequent studies and for institutions called upon to accelerate the global response to climate change. Our study’s primary limitation is the sample size, which prevents us from classifying the specific context of the trigrams analyzed in the news articles. While we can ensure that content on climate change is a relevant part in quantity and numerical effect of the daily news universe, we cannot guarantee that the reaction of the markets corresponds to the tone of this news content. Despite this limitation, linking specific topics to the reaction of financial markets in our study may open avenues for future research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.F., J.M. and E.t.H.; methodology, J.F., J.M. and E.t.H.; validation, J.M. and E.t.H.; formal analysis, J.F. and J.M.; investigation, J.F. and J.M.; data curation, J.F., J.M. and E.t.H.; writing—original draft preparation, J.F. and J.M.; writing—review and editing, J.F., J.M. and E.t.H.; visualization, J.M. and E.t.H.; supervision, J.M. and E.t.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

J.F. acknowledges financial support from the Credito Condonable de Doctorado of the Vicerector for Research of the University of los Andes and from Beca de Doctorado del Fondo Educativo Gabriel Vega Lara (no grant number and URL of funders). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The news stories were publicly available at Reuters news archive (www.reuters.com/article/, accessed on 8 January 2020) at the moment they were downloaded but the repository is not available anymore.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

List of most salient CCRTs common to all financial indexes that appear in both good and bad days and their loadings in the news index. This table presents the top ten percent salient CCRTs that are common to all financial indexes and have the greatest absolute difference between good (Q5) and bad (Q1). Green trigrams are the ones with positive differences which indicate they appear more frequently on good days than on bad days. Red trigrams are the ones with negative differences which indicate they appear more frequent on bad days than on good days.

Table A1.

List of most salient CCRTs common to all financial indexes that appear in both good and bad days and their loadings in the news index. This table presents the top ten percent salient CCRTs that are common to all financial indexes and have the greatest absolute difference between good (Q5) and bad (Q1). Green trigrams are the ones with positive differences which indicate they appear more frequently on good days than on bad days. Red trigrams are the ones with negative differences which indicate they appear more frequent on bad days than on good days.

| CCRT | Coefficient | CCRT | Coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|

| climat chang | 0.1356 | energi conf jun | 0.1081 |

| accord energi inform | −0.0433 | energi conf mar | −0.1063 |

| april brent crude | 0.1746 | energi enercom oil | 0.1777 |

| bank america energi | 0.1190 | energi erng conf | −0.0914 |

| barrel crude oil | 0.0475 | energi food price | −0.0849 |

| barrel light crude | 0.1221 | energi minist alexand | 0.0675 |

| barrel oil gas | −0.1412 | energi minist khalid | 0.1298 |

| boost energi share | 0.3306 | energi secretari sam | −0.1678 |

| boost oil price | 0.1509 | energi share fell | −0.2781 |

| brent crude fell | −0.1515 | energi stock fell | −0.3523 |

| brent crude lost | −0.2385 | energi stock rose | 0.1333 |

| brent crude rose | 0.1595 | energi tax break | −0.2225 |

| british energi bgyl | −0.1625 | expand oil gas | 0.1584 |

| broader climat pact | 0.2556 | extend tax credit | −0.1869 |

| carbon dioxid emiss | −0.0241 | exxon valdez oil | −0.3111 |

| carbon monoxid poison | 0.3284 | exxon valdez spill | −0.3129 |

| cliff natur resourc | 0.0633 | fall crude oil | −0.0992 |

| climat chang deal | 0.1132 | fall crude price | −0.1479 |

| climat pact replac | 0.2332 | fall oil price | −0.0558 |

| concern oil price | −0.1886 | fall price oil | −0.1476 |

| crisi oil price | −0.1626 | fell oil price | −0.3720 |

| crude clc fell | −0.2427 | fiveyear forward crude | 0.0945 |

| crude dow jone | 0.0415 | flood kill peopl | −0.1282 |

| crude fell barrel | −0.1701 | food energi compon | 0.1444 |

| crude fell settl | −0.5042 | food oil price | −0.1235 |

| crude futur cent | 0.0796 | frx oil rise | 0.1422 |

| crude futur fell | −0.1348 | fuel food price | −0.1096 |

| crude futur rose | 0.1581 | gain crude oil | 0.2072 |

| crude march deliveri | 0.1482 | gain energi stock | 0.1369 |

| crude octob deliveri | 0.2529 | gain oil price | 0.1830 |

| crude oil day | 0.1073 | gas carbon dioxid | −0.1194 |

| crude oil fell | 0.2186 | global carbon emiss | −0.1114 |

| crude oil gain | 0.2146 | global energi summit | −0.1038 |

| crude oil market | −0.0760 | global oil benchmark | −0.1575 |

| crude oil price | −0.0398 | global oil price | −0.0583 |

| crude oil rose | 0.1539 | global warm emiss | −0.2943 |

| crude palm oil | 0.0386 | gold crude dow | 0.0417 |

| crude price fell | −0.1753 | greenhous gas carbon | −0.1469 |

| crude price rose | 0.1017 | head climat chang | 0.1005 |

| crude rose barrel | 0.0943 | heat oil hok | 0.1989 |

| crude rose cent | 0.1823 | heat oil hox | −0.2052 |

| crude slip barrel | −0.1095 | high energi price | −0.0925 |

| cut fuel consumpt | −0.1500 | high oil price | −0.0722 |

| data fuel hope | 0.7193 | higher energi price | −0.1013 |

| data show gasolin | −0.1392 | howard weil energi | −0.0713 |

| declin oil price | −0.0709 | hurrican gustav ike | −0.1177 |

| drop crude inventori | 0.1179 | import iranian crude | −0.0836 |

| drop crude oil | −0.1153 | intern climat chang | 0.1435 |

| drop crude price | −0.1119 | intern energi agenc | −0.0252 |

| drop oil price | −0.0766 | jet fuel demand | 0.2414 |

| economi oil price | −0.1343 | juli heat oil | −0.1256 |

| emiss reduct target | 0.0624 | korea gas corp | 0.0775 |

| energi annual sharehold | −0.1132 | largest oil produc | −0.0463 |

| energi cnel ad | 0.3280 | lift oil price | 0.0856 |

| energi conf dec | 0.1072 | light sweet crude | −0.0543 |

| energi annual sharehold | −0.1132 | largest oil produc | −0.0463 |

| energi cnel ad | 0.3280 | lift oil price | 0.0856 |

| energi conf dec | 0.1072 | light sweet crude | −0.0543 |

| low level radiat | −0.4952 | oil price strong | 0.1245 |

| low oil price | −0.0429 | oil price threaten | −0.3011 |

| lower crude oil | −0.1416 | oil price trigger | −0.1679 |

| lower oil price | −0.0422 | oil price tumbl | −0.1806 |

| main oil export | −0.2173 | oil price weaken | −0.1482 |

| manmad climat chang | 0.1187 | oil price weigh | −0.1876 |

| nation hurrican center | 0.0361 | oil produc consum | −0.1558 |

| nation petroleum corp | 0.0526 | oil rose barrel | 0.1827 |

| natur resourc clfn | 0.1820 | oil sand mine | 0.0810 |

| novemb crude clx | −0.1593 | oil sand region | −0.1468 |

| nuclear fuel technolog | −0.2547 | oil slip barrel | −0.1589 |

| offshor oil drill | −0.1446 | petroleum invest compani | 0.1484 |

| oil clc fell | −0.2544 | plung oil price | −0.0836 |

| oil clc rose | 0.2083 | pressur oil price | −0.1951 |

| oil commod price | −0.1178 | price lift energi | 0.3428 |

| oil compani petroleo | −0.0788 | price oil commod | −0.0964 |

| oil drop barrel | −0.2980 | price weigh energi | −0.2209 |

| oil export port | −0.1606 | process barrel crude | 0.1461 |

| oil fell barrel | −0.1424 | pulp export copec | −0.2300 |

| oil futur clc | −0.0858 | record gasolin price | −0.1497 |

| oil futur fell | −0.1542 | record high oil | −0.2143 |

| oil futur rose | 0.2313 | record oil price | −0.2356 |

| oil gas conf | 0.0617 | recordhigh oil price | −0.1545 |

| oil gas develop | −0.0571 | renew energi project | 0.0601 |

| oil gas field | −0.0424 | rise energi cost | −0.0843 |

| oil gas index | −0.0536 | rise fuel cost | −0.0614 |

| oil gas price | −0.0469 | rise oil price | 0.0279 |

| oil hit low | −0.3753 | rose exxon mobil | 0.3001 |

| oil hit record | −0.1028 | run natur gas | 0.1616 |

| oil minist ali | −0.0666 | saudi oil minist | −0.0752 |

| oil price “ | −0.0485 | selloff crude oil | −0.3859 |

| oil price barrel | −0.0463 | shortag food fuel | −0.1300 |

| oil price continu | −0.1098 | slide crude oil | −0.2199 |

| oil price declin | −0.0761 | slide oil price | −0.1556 |

| oil price drop | −0.0966 | slump oil price | −0.0515 |

| oil price ea | 0.1544 | soar energi price | −0.2180 |

| oil price extend | −0.1199 | soar food fuel | −0.2220 |

| oil price fail | −0.2044 | soar oil price | −0.1860 |

| oil price fall | −0.0620 | spent fuel pool | −0.1360 |

| oil price fell | −0.1823 | spike oil price | −0.1208 |

| oil price gain | 0.1552 | spot gold crude | 0.0296 |

| oil price hit | −0.1183 | stateown energi compani | −0.0969 |

| oil price hurt | −0.1396 | strateg oil reserv | −0.1543 |

| oil price increa | −0.0725 | surg oil price | −0.1070 |

| oil price lift | 0.2781 | tax oil compani | −0.2101 |

| oil price lower | −0.0608 | tonn carbon dioxid | −0.0510 |

| oil price pressur | −0.1559 | tropic storm warn | 0.1531 |

| oil price push | −0.0594 | tumbl oil price | −0.2038 |

| oil price put | −0.1147 | ultralow sulfur diesel | −0.0739 |

| oil price resum | −0.1641 | unit state oil | −0.0986 |

| oil price rose | 0.1297 | uranium enrich plant | −0.2086 |

| oil price slide | −0.1067 | weak oil price | −0.0782 |

| oil price spark | −0.2167 | weil energi conf | −0.1029 |

| oil price stay | −0.1020 | won elect landslid | −0.1252 |

| oil price stoke | −0.3417 | world biggest emitt | 0.1308 |

References

- Stern, N. The Economics of Climate Change: The Stern review; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Furman, J.; Shadbegian, R.; Stock, J. The cost of delaying action to stem climate change: A meta-analysis. VoxEu, 25 February 2015. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. Report of the Conference of the Parties on Its Fifteenth Session, Held in Copenhagen from 7 to 19 December 2009. Addendum. Part Two: Action Taken by the Conference of the Parties at Its Fifteenth Session; Technical Report; United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change: Bonn, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Engle, R.F.; Giglio, S.; Kelly, B.; Lee, H.; Stroebel, J. Hedging climate change news. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2020, 33, 1184–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boissinot, J.; Huber, D.; Lame, G. Finance and climate: The transition to a low-carbon and climate-resilient economy from a financial sector perspective. OECD J. Financ. Mark. Trends 2016, 2015, 7–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaminker, C.; Stewart, F. The Role of Institutional Investors in Financing Clean Energy; OECD Working Papers on Finance, Insurance and Private Pensions; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, L. Catastrophe bonds and financial risk: Securing capital and rule through contingency. Geoforum 2013, 45, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gründl, H.; Dong, M.I.; Gal, J. The evolution of insurer portfolio investment strategies for long-term investing. OECD J. Financ. Mark. Trends 2016, 2, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameli, N.; Drummond, P.; Bisaro, A.; Grubb, M.; Chenet, H. Climate finance and disclosure for institutional investors: Why transparency is not enough. Clim. Chang. 2020, 160, 565–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacLeod, M.; Park, J. Financial cctivism and global climate change: The rise of investor-driven governance networks. Glob. Environ. Politics 2011, 11, 54–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansar, A.; Caldecott, B.; Tilbury, J. Stranded assets and the fossil fuel divestment campaign: What does divestment mean for 34 the valuation of fossil fuel assets? In Stranded Assets and the Fossil Fuel Divestment Campaign; Smith School of Enterprise and the Environment, University of Oxford: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ayling, J.; Gunningham, N. Non-state governance and climate policy: The fossil fuel divestment movement. Clim. Policy 2017, 17, 131–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, H.; Scheinkman, J.A. Climate Finance. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2020, 33, 1011–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachélier, L. Théorie de la Spéculation. Ph.D. Thesis, Sorbonne University, Paris, France, 1900. [Google Scholar]

- Antoniuk, Y.; Leirvik, T. Climate change events and stock market returns. J. Sustain. Financ. Invest. 2021, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, H.; Li, F.W.; Xu, J. Climate risks and market efficiency. J. Econom. 2019, 208, 265–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, D.; Gao, Z.; Jiang, W. Attention to global warming. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2020, 33, 1112–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giansante, S.; Fatouh, M.; Dove, N. Carbon emissions announcements and market returns. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, T.D.; Xia, Y. Climate change news risk and corporate bond returns. J. Financ. Quant. Anal. 2021, 56, 1985–2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venturini, A. Climate change, risk factors and stock returns: A review of the literature. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2022, 79, 101934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer, J.; Malagon, J.; ter Horst, E. Flooding in News? Building a Comprehensive News Index to Explain Financial Price Indexes. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4276329 (accessed on 11 August 2023).

- Taddy, M. Multinomial inverse regression for text analysis. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 2013, 108, 755–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentzkow, M.; Kelly, B.; Taddy, M. Text as data. J. Econ. Lit. 2019, 57, 535–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camargo, J.; González, M.; Guzmán, A.; ter Horst, E.; Trujillo, M.A. Topics and methods in economics, finance, and business journals: A content analysis enquiry. Heliyon 2018, 4, e01062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altman, E.I. Financial ratios, discriminant analysis and the prediction of corporate bankruptcy. J. Financ. 1968, 23, 589–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grafton, R.Q.; Nelson, H.W.; Lambie, N.R. A Dictionary of Climate Change and the Environment: Economics, Science and Policy; Edward Elgar Publishing: Camberley, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- US Forest Service. Climate Change Glossary. Available online: https://www.fs.fed.us/climatechange/documents/glossary.pdf (accessed on 17 December 2021).

- Matthews, J.R. IPCC, 2018: Annex I: Glossary; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Renneboog, L.; Ter Horst, J.; Zhang, C. Socially responsible investments: Institutional aspects, performance, and investor behavior. J. Bank. Financ. 2008, 32, 1723–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biagini, B.; Miller, A. Engaging the private sector in adaptation to climate change in developing countries: Importance, status, and challenges. Clim. Dev. 2013, 5, 242–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahmy, H. The rise in investors’ awareness of climate risks after the Paris Agreement and the clean energy-oil-technology prices nexus. Energy Econ. 2022, 106, 105738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venghaus, S.; Henseleit, M.; Belka, M. The impact of climate change awareness on behavioral changes in Germany: Changing minds or changing behavior? Energy Sustain. Soc. 2022, 12, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohleder, M.; Wilkens, M.; Zink, J. The effects of mutual fund decarbonization on stock prices and carbon emissions. J. Bank. Financ. 2022, 134, 106352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatib, S.F.A.; Ismail, I.H.M.; Salameh, N.; Abbas, A.F.; Bazhair, A.H.; Sulimany, H.G.H. Carbon emission and firm performance: The moderating role of management environmental training. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Abreu, V.H.S.; Santos, A.S.; Monteiro, T.G.M. Climate change impacts on the road transport infrastructure: A systematic review on adaptation measures. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madziel, M. Vehicle emission models and traffic simulators: A review. Energies 2023, 16, 3941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asness, C.S. Stocks versus bonds: Explaining the equity risk premium. Financ. Anal. J. 2000, 56, 96–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, G.; Gorton, G.; Rouwenhorst, G. Facts and Fantasies about Commodity Futures Ten Years Later; Technical Report; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greer, R.J. The nature of commodity index returns. J. Altern. Invest. 2000, 3, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorton, G.; Rouwenhorst, K.G. Facts and antasies about commodity futures. Financ. Anal. J. 2006, 62, 47–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).