1. Introduction

Cultural heritage refers to what humankind inherits from the past and utilizes in the present [

1]. When cultural heritage is focused on culture, it becomes a component of the identity of groups and individuals who share that culture, whether tangible or intangible. In addition, cultural heritage is a common asset that has economic, social, cultural, and educational value for human beings in the present. Therefore, it is not unreasonable to promote the utilization of cultural heritage in various fields. However, the way humans modernize their cultural heritage takes many forms, depending on the zeitgeist and generational differences. Sustainability has emerged as a prominent and timely concern in the realm of cultural heritage. Finding a balance between preservation and utilization is an important issue because cultural heritage does not belong only to the current generation but also to future generations. In particular, the consumption of cultural heritage through tourism has been identified as one of the biggest threats to cultural heritage. Consequently, it is important to pursue a sustainable relationship between cultural heritage and tourism [

2].

Meanwhile, digital media have had a significant impact on accessing and preserving cultural heritage, including in the tourism industry. In particular, digital media play a role in preserving cultural heritage in perpetuity or increasing access to it [

3]. It also plays an important role in the modernization and sustainable use of cultural heritage. As digital natives, Generation Z (that is, people who were born between 1995 and 2010) seeks more digitized and gamified experiences [

4] when it comes to cultural heritage. Furthermore, heritage experiences need to be reinvented as innovative experiences that reflect the needs of this generation [

5,

6]. Cultural heritage tourism has also been exploring innovative ways to attract visitors through cutting-edge technological advancements [

7]. In this context, location-based games (LBGs) are a new way to experience cultural heritage that reflects these changes. LBGs are games played in real spaces where the player is located, mediated by mobile technology [

8]. Among cultural heritage spaces and structures, those that hold memories of history and culture are particularly relevant to LBGs.

Furthermore, since cultural heritage sites are often tourist destinations, the combination of gaming and cultural heritage experience falls under the larger conceptual category of gamification of tourism. Gamification is “the process of game-thinking and game mechanics to engage visitors and solve problems” [

9], and it is utilized in various fields requiring user engagement, including tourism. In the tourism sector, practices and studies using game formats in all aspects of tourism (before, during, and after a visit/activity) to maximize tourists’ experiences are ongoing [

10]. The expected effects of integrating gamification in tourism include raising brand awareness, enhancing tourists’ experiences and engagement, and improving customer loyalty, entertainment, and employee management [

11]. Of these, LBGs are particularly related to tourists’ engagement with tourism destinations and points of interest [

12,

13].

Research on the gamification of tourism mainly aims to clarify tourists’ motivation to participate in games involving tourism destinations. Tourists’ motivation to play games involving tourism destinations is initially characterized by their search for information but later shifts to intrinsic stimuli such as fun, challenge, and a sense of accomplishment [

11]. Additionally, while game-playing has a strong impact on the motivation to visit tourism destinations, tourists tend to play games only when they have recreational value [

14]. Local residents who are not tourists also prioritize fun, competition, and rewards when playing LBGs [

15]. These studies show that tourists’ motivation to play LBGs is more focused on recreational purposes.

Research on the combination of LBGs and cultural heritage experience can be largely divided into two strands. The first, which is the dominant one, refers to the educational impact of cultural heritage experience through LBGs [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20]. The use of games in cultural heritage experiences can be motivating [

21,

22] and can foster collaborative learning [

23] and reflect on history [

24]. LBGs have also been shown to have a positive effect on learning, entertainment, social interactions, engagement, and change of attitude toward cultural heritage [

25]. In particular, the use of LBGs in cultural heritage experience has been shown to stimulate children’s imagination [

26] and to have a significant effect on their emotional connection to cultural heritage [

27]. These studies show that the purpose of combining cultural heritage experiences with LBGs is primarily to enhance educational engagement with cultural heritage. In the broader context of tourism, the purpose of LBG experiences is to engage and entertain, while when narrowed down to cultural heritage, the purpose of LBG experiences is to learn. This means that achieving authenticity in cultural heritage experiences needs to be deepened to the level of learning. On the other hand, this also means that when LBGs are used in cultural heritage experiences, they need to be more closely linked to the content of the heritage rather than simply being a tool to capture the content.

The second research strand aims to gain insights and develop guidelines for LBG development by studying actual LBG cases [

28,

29] or developing and testing LBGs [

12,

15,

30,

31,

32]. The problems and insights highlighted by these studies in LBG development can be categorized into two types.

The first type refers to connecting media technology with real cultural heritage destinations. This includes issues related to the accuracy of augmented reality (AR) and global positioning system (GPS) [

13,

33], motion recognition [

28], and installation of quick response (QR) codes [

12,

15,

30,

31,

32]. In particular, connecting participatory multimedia experiences to the site is challenging [

13]. Experiencing cultural heritage through LBGs is a mediated interaction between individuals and cultural heritage, facilitated by diverse media devices. Therefore, these studies emphasize that the accuracy or convenience of device operation is important for the LBG experience, but securing the stability of device operation is a difficult problem.

The second issue concerns the factors considered in the development of LBGs for cultural heritage experience. Among the previous studies, this issue is the most relevant to the topic of this research. The research of Ballagas et al. [

28] presents six insights obtained from their self-developed LBGs, three of which address the balance of cultural heritage experience and gaming. These are the issues of (1) whether to focus more on the game itself or on tourism, (2) whether the game restricts visitors’ movement, and (3) how to balance education and entertainment [

28]. Xu and Weber’s research shows that for a game to provide meaningful cultural heritage experiences, not only extrinsic rewards, such as points or treasure, are needed but also intrinsic rewards, such as relatedness, competence, and autonomy [

34]. Weber argues that the extrinsic rewards presented by LBGs should not be emphasized over the intrinsic rewards presented by cultural heritage experiences. Rubino et al., suggest that LBGs can be a suitable solution for enhancing cultural experiences in museums [

35]. However, they point out that while the game allows for extensive exploration of the museum, players will only acquire superficial knowledge of the proposed content [

35]. Similar to Weber, they point out that the use of LBGs can lead to a superficialization of the cultural heritage experience. Luiro et al. present the development process of a game based on Finnish history and cultural heritage and suggest that it is challenging to strike a balance between historical accuracy and an engaging narrative [

36]. They appeal to the difficulty of combining the historical facts of cultural heritage with the narrative fiction of LBGs.

In summary, the abovementioned studies show that combining LGBs and cultural heritage experiences is a challenging endeavor, involving disparate elements such as new media devices and cultural heritage, entertainment and education, and historical facts and fictional stories. These studies also caution against overwhelming the cultural heritage experience with the gaming experience when using the latter to enhance the former. However, while there is consensus on the challenges and difficulties of combining LGBs and cultural heritage experience, there is a lack of research on how to optimize it.

Therefore, this study presents a model that can guide the development of LBGs from the perspective of combining cultural heritage experiences and games, focusing on the experiences of Generation Z. Using LBGs for cultural heritage experiences is one way in which Generation Z is modernizing heritage. Moreover, since utilizing LBGs in tourism involves combining the heterogeneous experiences of the digital environment (mobile devices), the analog environment (actual location), gaming and cultural heritage experience, and fun and education, more focused research is needed. However, while demand for utilizing LBGs in tourism is increasing, there is a lack of guidance for developing such services.

Therefore, this study aims to explore a model for the effective combination of gaming and cultural heritage experience in LBGs by examining the experiences of actual visitors during gameplay. For this purpose, participants from Generation Z, who are digital natives, played the LBG Jeongdong Milseo, which is available in South Korea. Subsequently, data on the gameplay process were collected from the perspective of combining cultural heritage and gaming experiences through focus group interviews. The collected data were analyzed using grounded theory methodology, while a model for combining cultural heritage experience and gaming in LBGs was created. The present study is expected to facilitate understanding regarding the combination of heterogeneous elements such as digital and analog technologies or gaming and cultural heritage experience and serve as a model for developing LBGs for cultural heritage experience.

Research Question 1: How can the heterogeneous experiences of cultural heritage and gaming be combined in LBGs?

Research Question 2: How does Generation Z perceive cultural heritage experiences through LBGs?

3. Results

According to the data analysis results, 87 concepts were constructed in the initial coding process, and similar concepts were condensed into 55 categories, as shown in

Table 4. The 55 categories were focus-coded into 11 categories, while during theoretical coding, the 11 categories were further reduced to 4 categories.

3.1. Site-Based Play

3.1.1. Conflict between Game Completion and the Physical Environment

Because LBGs are games played in real spaces, participants experienced conflict between the goal of experiencing the game’s ending and the physical environment. In particular, the hot weather and the size of the gameplay area were problematic. In the context of the general cultural heritage experience, visitors can adjust their schedule depending on the weather or the environment of the destination. However, in the case of games, once started, visitors make an implicit commitment to play until the end, and poor physical conditions tend to undermine their motivation to continue playing. In the case of Jeongdong Milseo, the estimated playtime suggested by the app was about three hours, but the actual average playtime of the 15 participants was about two hours. Moreover, the play area is approximately 158,225 m2. The fact that the participants finished the game more quickly than the estimated playtime suggests that the weather and the size of the play area contributed to the burden. Additionally, participants could not quit the game halfway and had to play until the end to participate in the study, which also seems to have acted as a burden.

I felt that movement took too long, both in terms of time and distance. After reaching Jungmyeongjeon Hall of Deoksugung, I started to feel tired.

(Participant 2)

I checked my step count at that time; I had walked over 10,000 steps.

(Participant 12)

Time constraints also acted as a physical barrier to gameplay. The game itself has an estimated playtime but no specific time constraints. However, since the participants started the game at different times, for those who started late in the afternoon, the closing hours of facilities like the exhibition hall and Deoksugung became a time constraint. Participants used expressions such as “guideline”, “struggle”, “hurry”, and “burden” regarding these physical constraints, expressing that the temporal, spatial, and physical environments were obstacles to completing the game. Some participants also expressed that they would like the playtime to be shorter. Since LBGs are played in actual time and space, it is essential to set the game’s time and space appropriately to ensure game completion.

3.1.2. Conflict between Game Completion and Tourism

While the physical environment posed obstacles to completing the game, game completion itself became a problem by acting as an obstacle to tourism. As discussed in the introduction, according to previous studies, game formats that provide goals and rewards help visitors engage with cultural heritage destinations. However, participants commonly felt they lacked the psychological leisure to fully enjoy the tourism destinations, as they were focused on the game’s missions and outcomes. Many participants used expressions like “clearing” the game or missions, which demonstrates the nature of a game that cannot be quit halfway.

When you visit the location and clear the mission, you have to move on to the next one right away. Usually when you hear “Please go to the next location”, you just go in that direction. So before leaving, I did not have thoughts like, “Should I take a look around here before moving on?” As a result, I feel like I went to many places, but despite the fact that they are valuable cultural heritage sites, my understanding of the places themselves is lacking.

(Participant 6)

One participant felt that they could only play the game “well” by completing it in less time than the three hours suggested by the app. Also, many participants regretted that they could not fully enjoy the cultural heritage destination while playing the game. This created motivation for revisiting the tourism destinations but also confirmed that they experienced psychological conflict as the “sense of achievement” from playing the game and the “freedom” or “leisure” of the cultural heritage experience were in conflict. The goal-oriented nature of games has the power to present goals to players and strongly engage them in achieving those goals. However, when this goal orientation is focused on the game, it can have a counterproductive effect on engagement with the tourism destination. A game structure that does not interfere with cultural heritage experience while still following the game’s goals is necessary.

3.1.3. Linear Missions with a Set Order

The research results indicated that the starting and ending points of gameplay in LBGs are important. Since LBGs are games played in real spaces, the process of going to a cultural heritage destination to play the game and then leaving the cultural heritage destination after finishing the game must be considered. The start and end of the game do not take place in a single location, such as in front of a monitor like in digital games. Because of this, participants wanted to know beforehand where the game starts, where it ends, and how many places they have to visit to play the game. Generally, in digital games, not knowing the next mission helps keep players motivated for the game. However, participants also perceived the missions in the location-based game as a sort of guide revealing the experience route.

The game felt like a guide. It felt like it was guiding the way, and I had to go to the places it told me to.

(Participant 9)

The sequential nature of the missions also posed an issue during gameplay. Cultural heritage guides present cultural heritage destinations in a certain order, but in reality, there is no need to strictly follow the guide’s suggested order, and skipping certain places is not a problem. However, in games like Jeongdong Milseo, completing the previous mission is a prerequisite for the next mission, leading to a forced sequential nature. The inability to skip or choose the order of missions was found to hinder participants’ engagement.

While doing a mission at Deoksugung, I came across a beautiful spot and went to take a picture. After taking the picture, when I tried to resume the mission, I had to retrace my steps. This happened several times, which made the game less interesting and somewhat annoying.

(Participant 13)

As the sequence was enforced, participants who wanted to momentarily step out of the game to enjoy the cultural heritage destination had to retrace their steps to resume the mission. Some participants did not even consider deviating from the mission route due to the sequence’s compulsory nature. Cultural heritage guides also present linear routes to visitors. However, a cultural heritage guide’s “suggested” order and a game mission’s “compulsory” order are different. Therefore, it is necessary to design LBGs with linear routes but missions without a set order.

3.1.4. Rediscovering Cultural Heritage Sites

The participants felt satisfied when game missions were connected to the cultural heritage destination. Eight out of fifteen participants had previously visited the area, and they expressed satisfaction in learning something new through the game. The participants with prior visits used expressions such as “details”, “minor things”, “discovering things I did not know”, “new”, and “in-depth” to convey that they had new experiences even during a revisit. In particular, many participants expressed satisfaction with quizzes involving numbers written on tombstones in Deoksugung or patterns on the cathedral walls.

I was able to visit places that I might have just passed by, thinking it was just an alleyway. At Deoksugung, there was a mission to check the patterns inside the columns. Through this, I learned that the patterns were different on each column, and it was nice to take a closer look at places that I would usually just pass by.

(Participant 8)

In the research results presented above, within the macroscopic cultural heritage destination experience (moving between places and missions), the gaming experience (a kind of compulsory activity) overpowered the cultural heritage experience. However, at the microscopic level of experiencing places and objects, the results showed that connecting the game with the cultural heritage destination allowed players to rediscover cultural heritage sites. When increasing engagement with cultural heritage destinations through games, it is more effective to enhance the experience within a single location rather than connecting multiple locations.

3.1.5. Site-Based Quizzes without the Actual Site

The sense of presence in the quizzes was an essential factor in determining participants’ engagement. Participants who felt a connection between the mission and the site felt satisfied after completing the mission. In particular, participants often used the term “directly” when expressing satisfaction, feeling that the mission and site were closely linked.

What left the deepest impression was when I had to look at the numbers on the tombstones with my own eyes, and then apply them to the picture (mission letter quiz) to find the combination.

(Participant 10)

Conversely, participants stated that their engagement decreased when they encountered quizzes that did not sufficiently utilize historical or cultural heritage knowledge or when they encountered quizzes that did not necessarily need to be solved at a specific location.

They were not based on historical knowledge but on skills used in escape room games, which I did not even play in the first place. I wondered why I would pay for such a tormenting experience when it would be better to implement more historical knowledge, such as searching for things on the internet or using the Deoksugung map.

(Participant 4)

Missions (composed of multiple quizzes) that occupy a large portion of the gameplay are the medium that combines cultural heritage and gaming experiences. Generally, games have a structure that maintains engagement by gradually increasing the intensity of challenges through systems like levels. For this reason, players also consider mission difficulty when choosing a game to play. However, in designing missions for LBGs that integrate cultural heritage experiences, it seems that how closely the mission is connected to the cultural heritage destination is a more critical factor than the mission’s difficulty in determining engagement.

3.1.6. Inaccurate and Failed Feedback

Jeongdong Milseo is designed as a combination of a mobile app and mission letters, integrating AR features when solving quizzes. AR is used three times in Jeongdong Milseo, and participants felt more engaged with the site when AR recognition was successful. However, when AR recognition failed, their engagement with the game was affected. Visitors described this as “losing momentum”, “losing motivation”, or “feeling empty”.

Particularly, the first AR feature in the cathedral was replaced with an alternative quiz due to construction inside the cathedral, which negatively affected the gaming experience. Thirteen out of fifteen participants had negative opinions about the use of AR in the Cathedral Quest. Additionally, the map provided in the mobile app did not accurately show the locations necessary for gameplay, and the need to use multiple media inconvenienced the participants.

In my case, there were problems with the AR, as it suddenly stopped working on my phone. When that happened, it offered hints as a substitute, but that was somewhat disappointing. Up until that moment, I felt immersed in the game, but after that, it felt more like just a mobile game, which was disappointing.

(Participant 7)

Conversely, one mission required participants to solve quizzes to find a phone number; upon calling that number, a voice actor portraying an independence activist would present the next mission. Participants commonly expressed that they felt as if they were actually participating in the independence movement during this mission.

During the game, we had to make a phone call. My immersion had already broken at the cathedral, but when I made the call I thought, “This is so crazy”, and became re-immersed in the game, even if just a little.

(Participant 9)

Regardless of the sophistication or diversity of the technology used in the game, it is essential for the game to provide appropriate and accurate feedback (reactions) when visitors take action during gameplay. Even though the phone call mission did not use new technology like AR, it led to a positive experience through successful feedback. While missions serve as the medium connecting the cultural heritage experience and gaming experience in terms of content, various mobile technologies physically connect the cultural heritage destinations with the game. Therefore, although it is important to create high-quality game content, accurate feedback from mobile technologies connecting the physical cultural heritage destinations and the game must be prioritized.

3.2. Loose Story

3.2.1. Disrupted Roleplaying

Jeongdong Milseo assigns participants the role of an independence activist and invites them to participate in the game through this role. When participants purchase the game on the app, mission letters (secret letters in the story) are delivered to their homes. Participants stated that this format helped raise their expectations for the game. This roleplaying plays a crucial role in strengthening the game’s engagement through its narrative elements.

Also, even if seven of the fifteen participants had never visited the Jeongdong area before, most of them were aware through school education that the area was closely related to historical events during Japanese rule. Because of this, they easily recognized the story’s subject matter and the role assigned to them, and they positively assessed that it suited the Jeongdong area.

When I was going from Deoksugung to Gyeonggyojang, the buildings were still old like in the past, so I felt like I had become a real independence activist for a moment.

(Participant 5)

It was not the story itself but the historical nature of the Jeongdong area and the authenticity of historical buildings that helped participants immerse themselves in the fictional story. However, this realism of the gameplay sites did not only help participants engage with the story through their roles. Participants expressed that there were too many things to pay attention to (e.g., the weather, surrounding noise, quiz difficulty, and other environmental and gameplay elements) before they could immerse themselves in the role of an independence activist. The physical inconvenience of having to alternate between mission letters and the mobile app also hindered participants from immersing themselves in their roles.

Honestly, I did not feel like I had become an independence activist. I tried, but there were too many distractions for me to immerse myself in the role, including the weather.

(Participant 9)

In general, games with narrative elements involve the player taking on the protagonist’s role in the first person when playing the game. Immersing oneself in a role is not easy, even in a controlled environment provided by a single medium like a computer. It is even more challenging in an LBG, where players have many things to pay attention to. Therefore, instead of forcing players to maintain immersion in a particular role, it may be more suitable to structure the story in an omnibus format that allows them to experience the story regardless of any distractions.

3.2.2. Interaction with Characters

In terms of the narrative, participants commonly evaluated their interactions with the game’s characters positively. In the early mission at the cathedral, participants received confirmation that they were members of the Guangwu Association from a priest, who was also an independence activist. In the middle of the game, during a phone mission, they received praise and encouragement for their mission from another independence activist. Participants expressed that they felt emotionally engaged in the story through these missions. Particularly, most participants mentioned the game’s ending. At the end of the game, participants deliver independence funds to Kim Gu at Gyeonggyojang and hear his eloquent speech urging independence.

When I was delivering the funds and having a conversation with Kim Gu, that scene was emotional because it closely overlapped with what I learned about Gyeonggyojang from my history studies. Gyeonggyojang is where Kim Gu stayed and also where he was assassinated. That experience of being able to have a conversation with him at Gyeonggyojang itself was very moving for me.

(Participant 15)

Rather than experiencing narrative-related emotions through the overall narrative (i.e., the plot or storyline), participants were more engaged in the story through interactions with the characters. Therefore, instead of having participants follow the plot through missions, having different characters interact with them at each location or mission could be an alternative to enhance the player’s narrative experience.

3.3. Mutually Pervasive Environments

3.3.1. Outdoor Environment: A “Magic Circle” with Holes

The fact that the game was played outdoors also affected participants’ gameplay and satisfaction. Though playing the game outdoors was a “fresh” and “novel” experience, the outdoor environment also had many distractions. Despite playing the game in May, participants commonly experienced negative impacts on gameplay due to unusually hot weather. Additionally, the game’s location near Gwanghwamun, an area with many protests, resulted in distractions due to noise from protesters.

When I came out of the City Hall station, it was a weekend afternoon, so the whole street was full of protesters. So, I guess there were issues like the weather and the time. There was an intense heat wave when I played the game, and I did not think about environmental constraints like that.

(Participant 10)

The outdoor urban environment not only contains physical obstacles such as weather and noise but also the potential for psychological obstacles. In LBGs, tourism destinations and game spaces are also everyday spaces. Focusing on the game’s fictional context while in a crowd of people in daily life is not only difficult but also causes a sense of alienation.

I was on my way home from work. Playing this by myself in a crowd as if I were the only one who was really busy was slightly embarrassing. It might not be something that I would do on my own.

(Participant 12)

In outdoor games like LBGs, it is difficult to block out the surrounding environment and create a solid “magic circle”. Instead, games can be designed to incorporate various elements of daily life from the outdoor environment and real-life context. Although factors such as the weather may be difficult to control, other elements, such as protesters and commuting crowds, can be incorporated into the story as “busy pedestrians on the streets of Gyeongseong in 1919”.

3.3.2. Social Environment: Lack of Human Interaction

Participants felt that there was a lack of human interaction during the game. This is ironic considering that participants felt the surrounding crowds were a hindrance to their immersion in the game. However, the lack of human interaction was related to the participants’ desire to engage with other people in the game. Six out of nine participants who played the game alone experienced discomfort in using the mobile app, difficulty in solving quizzes, and a psychological sense of alienation, whereas those who played with a companion had a more positive experience.

I solved some questions and my friend also solved some too. It was definitely easier to solve the questions when we put our heads together, and it would have been somewhat embarrassing to walk around playing the game alone, so I played it with my friend.

(Participant 3)

Participants expressed their disappointment at the lack of interaction with on-site staff, such as those at the exhibition hall or Deoksugung. This suggests that in LBGs, not only the connection between the cultural heritage and gaming experiences is important, but interaction with local residents is also a crucial element. Therefore, designing the game to allow for solving quizzes with a companion or other people or allowing players to seek help from staff at cultural heritage destinations could help engage players in the game.

3.4. Generation Z’s Ambivalent Satisfaction

Observing the participants’ responses and conversations regarding their overall satisfaction with the Jeongdong Milseo experience, the researcher strongly felt that participants experienced ambivalence about their experience. This was common across all three groups. Twelve out of the fifteen participants could not clearly say whether they liked or disliked the Jeongdong Milseo experience. Most responses took the form of “some aspects were good, but others were disappointing”.

3.4.1. Ambivalence about the Gaming Experience

Ambivalence about the gaming experience stemmed from the game being novel and interesting in some respects but falling short of the expectations of adult participants. As the game was centered around historical material, its educational nature was not conducive to making the game “fun”. Generation Z participants identified themselves as adults and demanded sophisticated, adult-appropriate experiences. Moreover, satisfaction with the gaming experience was also related to participants’ prior gaming experience. In other words, the participants, who were familiar with sophisticated mobile games, found the game content simplistic, falling short of their expectations, and unsuitable for adult audiences.

I think the content itself is a little lacking for adults to play right now. It might be helpful for children, but I’m not sure if adults would really make time for this. I think it would be helpful to prepare more content for adults.

(Participant 13)

3.4.2. Ambivalence about the Cultural Heritage Experience

Ambivalence about the cultural heritage experience was related to the authenticity of the experience. Participants used expressions like “unable to experience deeply”, “unable to truly appreciate”, “not touching”, and “superficial”. This suggests that participants had expectations for a genuine or deep experience, as the cultural heritage destinations they experienced through Jeongdong Milseo were related to Korea’s heart-wrenching historical heritage.

Since I do not usually visit historical sites for fun, it is true that this game gave me a starting point to go there, but it felt like I only experienced it without really learning anything. When I visit historical sites, I usually try to see and think more about what kind of place it is and what meaning it holds, but when playing the game, I was too focused on moving on to the next part, so I think I missed out on the learning I would have done if I had just gone there normally.

(Participant 12)

Participants’ dissatisfaction with the gaming experience was attributed to the historical aspect of the experience, while those who were dissatisfied with the tourism experience felt that the game triggered interest in the cultural heritage destinations but lacked depth and authenticity in the experience. This suggests that, for Generation Z, cultural heritage destinations are not places they would be motivated to visit without a specific purpose and that the use of games can be an incentive to visit these places. However, for the LBG experience to be authentic, the combination of gaming and heritage requires a deeper level of integration.

3.5. Structure Combining Cultural Heritage Experience and Gaming Experiences in LBGs

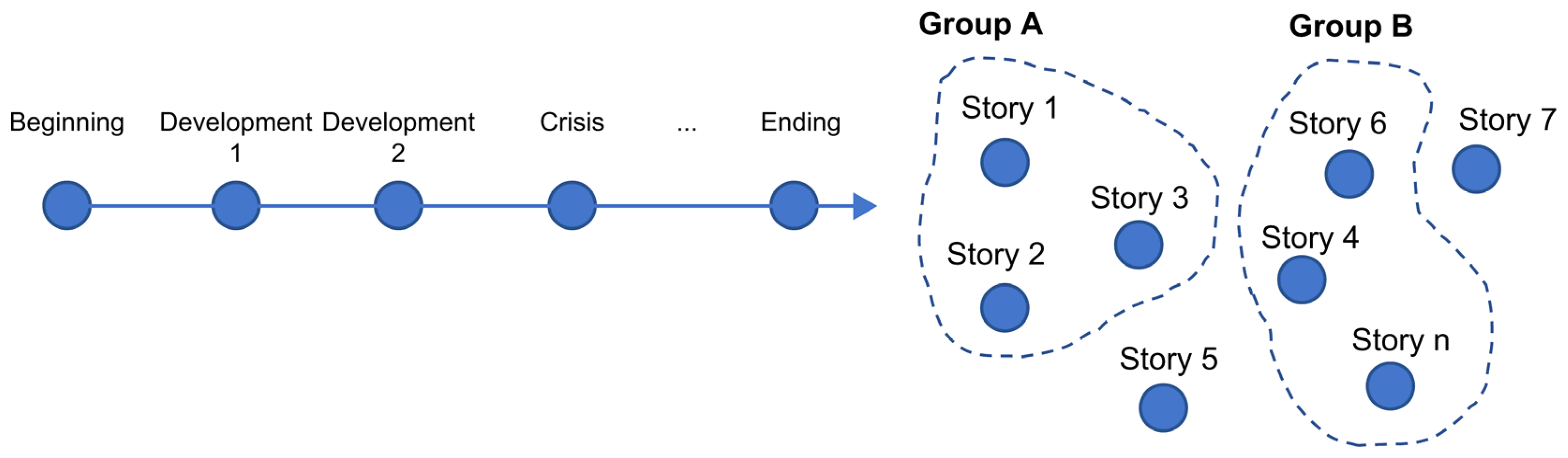

Reflecting the results of focused coding, this study created a theoretical structure for combining cultural heritage and gaming experiences in LBGs, as shown in

Figure 4. The results of focused coding were derived based on factors that hinder the combination of cultural heritage and gaming experiences, and these were converted into improvements and incorporated into the theoretical structure. The derived LBG structure consists of elements of play, story, and environment. In this case, the missions are what connect the elements of play, story, and environment into a single game. In LBGs, missions determine under what environmental conditions a player will solve a quiz and experience a story. They become the point of contact and intersection between gaming and cultural heritage experiences.

First, play in LBGs must be thoroughly based on the actual site of the cultural heritage destination. One method for this is to structure play with missions that have no predetermined order. The first factor that caused conflict between gaming and cultural heritage experience for participants, as identified during focused coding, was that the gameplay took a long time or covered a large area. To solve this problem, visitors should be able to choose the missions that they can play. For example, in Jeongdong Milseo, participants had to complete all eight missions, but allowing them to selectively complete only a few missions and still finish the game would enable tourists to adjust the time and space of gameplay according to their preferences.

The inability to choose not only the missions but also the order of solving them were factors that caused conflict between gaming and cultural heritage experience for participants. To solve this problem, tourists should be able to choose not only the number of missions but also the order in which they complete them. This way, the compulsory nature of the game will not undermine the autonomy of tourism. This alternative can be visualized and represented as shown in

Figure 5. The left figure represents the current mission structure of

Jeongdong Milseo, while the right figure represents the alternative mission structure. As shown in the right figure, visitors should be able to complete the game by performing only missions from Group A or only missions from Group B. Within each group, players can also decide the order in which they complete the missions. Highly motivated visitors may complete all the missions, whereas others can enjoy the game without interfering with the cultural heritage experience if they only complete a portion of the missions.

The second method is to have missions centered on objects at the sites. Participants felt that cultural heritage experience and gaming were closely related when they discovered cultural heritage through the game’s missions, which they would not have learned about without guidance. Conversely, when the game was not connected to elements at the sites, such as buildings or objects, participants felt skeptical about the gameplay itself. Ultimately, in LBGs, the combination of cultural heritage and gaming experiences must be linked not only on a macro level (connections between sites, route suggestions, etc.) but also on a micro level, such as buildings or objects, for all quizzes and missions.

The third method involves an accurate feedback system. Participants found that their motivation for gameplay was significantly reduced when features such as maps or AR in the mobile app did not function correctly or required workarounds. Mobile apps are the most basic medium connecting destinations and games, physically linking cultural heritage destinations and gaming. Therefore, when combining tourism and gaming in LBGs, accurate app feedback is not optional but a necessary condition. As such, when designing a game, while it is important to create diverse and high-quality content, the developer must ensure that the app functions correctly under various circumstances.

In LBGs, the second element of combining tourism and gaming is the story, which should be loose. Since LBGs use various media and are played in the real world, it is difficult for players to fully experience a single, complete story with a beginning and an end. The loose story must also be accompanied by a site-based play.

As shown on the left side of

Figure 6, the current narrative of

Jeongdong Milseo has a clear linear structure where players are given the mission of delivering independence funds and go through various events. However, LBGs have a structure where players experience the play and story simultaneously through missions. Therefore, if visitors can choose play experiences without a predetermined order, the story should also be experienced in the same way. The right side of the figure shows the alternative method where players can experience the story selectively and in any order without affecting the gameplay. In this case, an omnibus format is suitable, with each story (Stories 1–6) as a separate, complete story rather than part of a larger narrative that connects to other stories. Additionally, having characters interact with players in each story can be effective in providing emotional experiences throughout the story. For example, by applying this format to

Jeongdong Milseo, players can meet different independence activists in each mission, listen to their stories, and interact with them. This way, even if players do not experience all the stories, it will not affect their gameplay.

Finally, the third element of combining cultural heritage experiences and gaming in LBGs is mutually pervasive environments. LBGs are played in real-world spaces, so various physical and psychological factors inherently “invade” the gaming experience. Participants felt that these real-world factors interfered with their LBG experience. However, instead of blocking out the surroundings and creating a solid “magic circle” of fiction, accepting the inherent characteristics of LBGs and allowing various contexts of the real world to “pervade” the space by creating an open magic circle could be a better strategy. Participants often used expressions like “I felt immersed” or “My immersion was broken” during the coding process. This suggests that based on their experiences with traditional digital games, participants have a preconceived notion that a good game is one that can be played with complete immersion, blocking out the surroundings. Therefore, it could be a better strategy to actively utilize the real-world context in LBGs by including on-site objects and people in the game’s mission design. This way, players can accept values other than immersion as virtues of the LBG gameplay.

4. Discussion

From the results of this study, three discussion points pertaining to the research problem emerge.

The first discussion point is the issue of Generation Z’s perception of cultural heritage experiences through LBGs. Similar to the findings of previous studies that LBGs have a positive impact on visitation intentions for tourist destinations [

14], participants in this study also perceived LBGs as helpful in encouraging them to visit cultural heritage sites. These perceptions demonstrate a lack of willingness to visit cultural heritage sites in cities unless they have some purpose or meaning. In particular, participants in the study found that the LBGs they played sparked their interest in cultural heritage destinations, even though they had a low opinion of the game experience itself. This suggests that Generation Z has a high level of demand for such experiential content as they are exposed to a variety of digital content, including games, on a daily basis. This also ties in with their perception of educational experiences through LBGs. Generation Z needs fast interactions that can satisfy their curiosity and provide instant gratification [

5,

6]. This is not to say that Generation Z is only looking for fun and rejecting educational experiences when it comes to LBG-enabled cultural heritage experiences. However, they want their experiences to be differentiated by small details that can only be discovered through on-site gameplay rather than information that can be learned without the use of a game. This relates to the question of the sustainability of using LBGs in cultural heritage experiences. The use of LBGs in cultural heritage experiences is not just about engaging people through the form of a game. LBGs can provide a new cultural context for cultural heritage that cannot be physically altered, whether it is a fictional story or has educational content. This aligns with Gen Z’s cultural tendency to seek out new, personalized experiences. The sustainability that LBG can provide to cultural heritage is not the physical sustainability of preservation but rather the cultural sustainability of being able to present new values to suit the changing times.

They also want historical information to be woven into the mission rather than simply delivered superficially through a game. The development of LBGs that target Generation Z shows that the combination of a game and a cultural heritage experience needs to be more carefully designed. Experiencing cultural heritage through LBGs once again emphasized that “Generation Z is a social generation” [

43]. In the study, participants who played the game with a companion were clearly more satisfied than those who played the game alone. They also wanted to interact with others on-site while playing the game. They felt uncomfortable being cut off from their surroundings and forced to immerse themselves in the game. It is natural for Generation Z, as digital natives, to move fluidly between physical and online environments [

44]. Therefore, a more effective model for LBGs based in physical environments, especially when targeting Generation Z, is to incorporate games that allow for active networking with others, both online and offline, rather than isolated immersion.

The second discussion point refers to what happens if LBGs do not achieve a balance between gaming and cultural heritage experiences. One possibility is that the reversal of roles, as cautioned in previous studies, can easily occur [

13,

28]. In the tourism sector, LBGs are mainly used as a way to enhance tourist engagement and enrich experiences at tourism destinations. However, an interesting finding is that the participants showed clear ambivalence in their experience of

Jeongdong Milseo, reporting positive and negative aspects of both cultural heritage and gaming experiences. Generally, gamification, which involves applying gaming to other fields, is notable for two aspects. First is the goal-oriented aspect of gaming that focuses on achievement and victory, and second is the immersive and interactive aspect of digital media. However, the ambivalence shown by the study participants indicates that these two aspects, which are reasons for playing games, can be obstacles to engagement in cultural heritage experiences. The pressure to quickly achieve the game objectives can interfere with the autonomy and authenticity of the visitor’s experience. Additionally, immersion in and various interactive requirements for playing the game (such as operating mobile apps or utilizing maps) can also interfere with elements such as the autonomy of cultural heritage experiences and serendipitous discoveries.

Finally, the third discussion point is linked to the second: the issue of “balance” and “combining” among the various considerations for combining gaming and cultural heritage experiences in LBGs. This study proposed three elements—play, story, and environment—as considerations for the aforementioned. The fact that these three elements are important in the combination of gaming and cultural heritage experiences is not completely new and has been revealed in existing studies. In LBGs and the gamification of tourism, several studies suggested play-related elements such as scores and rewards to help the tourist experience [

14,

34], and the importance of story experience in the gamification of tourist attractions has also been emphasized [

10,

11,

45]. Moreover, the importance of socialization elements in LBGs, such as interacting with accompanying participants or locals, has also been discussed [

10,

11,

45]. However, the current study has gone beyond identifying each element and explored how these important elements intersect and interact based on missions in constructing a single experience. In LBGs, although play, story, and environment are important elements in enhancing the visitor’s experience through the game format, it is important to ensure that they can create mutual synergy without interfering with each separate experience.

5. Conclusions

Combining cultural heritage experiences with new technologies is an inevitable direction for Generation Z, who are accustomed to experiences mediated by digital media. This study confirms that Generation Z has high expectations for the integration of gaming and heritage experiences, and it is expected that the model presented in this study can help facilitate such integration.

This study explored methods of combining the heterogeneous experiences of cultural heritage and gaming in LBGs through the methodology of grounded theory, with a focus on the experiences of Generation Z. According to our results, the participants experienced ambivalence between cultural heritage and gaming experiences. This ambivalence expressed by participants suggests Generation Z’s perception of LBGs. As digital natives, Generation Z wanted a higher level of integration of cultural heritage and gaming experiences and wanted to experience expanded social networking.

Furthermore, this study presented alternative methods to solve these hindrances within the structure where play, story, and environment intersect through the theoretical coding process. First, three alternatives for site-based play are proposed: missions with no predetermined order and optional play, missions centered around objects at the sites and an accurate feedback system. Second, two alternatives for a loose story are proposed: an omnibus-style story and a character-centered story instead of a plot-driven one. Finally, two alternatives for mutually pervasive environments are proposed: open “magic circles” and human interaction design.

Of course, there are limitations to the research results presented in this study. The main issue is whether this theoretical structure can secure sufficient universality. The fact that this study focused on a single LBG played in a specific environment can be a limitation. These limitations can be addressed in future research with a wider range of LBG experiences. However, in this study, the author attempted to derive a meaningful theoretical structure from the research data by repeatedly going through the initial coding and focused coding processes over six months. Furthermore, it is expected that the theory derived from Gen Z study participants’ experiences can serve as a practical methodology for LBG development.

In the age of convergence where media and content form networks, tourism is also moving toward integrating various content and utilizing multiple media. LBGs introduce fictional plays or stories into cultural heritage destinations in urban spaces where change is difficult or slow, providing a new context of experience by overlapping them. In this respect, LBGs can serve as a method to make urban cultural heritage destinations not just a part of everyday life but a place to visit repeatedly, enabling sustainable tourism. From a sustainability perspective, LBG’s approach to renewing cultural heritage is one that achieves cultural sustainability without compromising physical sustainability. In addition, LBG’s use of games and digital media to sustain cultural heritage is in line with the characteristics of Generation Z, who will be the main players in preserving and utilizing cultural heritage in the future.