Abstract

Plant-based milk products are ultra-processed food products that enjoy a positive reputation as being safe, healthy, ethical, and sustainable. The present study is focused on these products and addresses the product and brand managers of US food retailers. A consumer survey explores the factors explaining US consumers’ preferences for and commitment to plant-based milk and other plant-based milk products. Environmental concerns, food safety, health, and sustainability concerns are identified as relevant predictors for both consumer behaviors. In addition, animal welfare concerns are relevant, but only for product commitment.

1. Introduction

In the past decade, climate-conscious and healthy living has become increasingly popular in many Western societies [,,]. In this context, ultra-processed foods have received negative attention among academics and media [,]. It is often disregarded that plant-based milk alternatives fall into the category of ultra-processed foods, and, in contrast to products such as breakfast cereals, instant soups, and carbonated beverages, they enjoy the image of being a more ethical, sustainable, and healthy product [,,]. Plant-based milk alternatives fall into the category of ultra-processed foods as they are plant-based water extracts stemming from grains, legumes, nuts, and seeds aiming to emulate dairy milk []. Any ultra-processed food is required to first be fractioned into substances and then reassembled into a product. Stabilizers, salt, non-caloric sweeteners, vitamins, and minerals may be added to the product []. Some ultra-processed foods aim to emulate wholesome unprocessed or minimally processed foods, and the production of plant-based milk alternatives is no exception []. This ultra-processing serves multiple purposes, including enhancing the product’s shelf life and imitating the taste, appearance, and texture of regular dairy-based milk []. Ethical and climate-conscious US consumers, as well as those following a vegan diet or those with dietary restrictions such as lactose intolerance or cow milk protein allergies, commonly favor plant-based milk alternatives [,,,]. Consumers with lactose intolerance often favor buying plant-based milk products over taking pills to help them digest lactose, as these medications can be rather expensive []. Consumers with cow milk protein allergies have no other option but to remove cow milk from their diet. These consumers need to be very attentive to labeling when buying processed food items, as small, unintended amounts of the allergen may be present, often cross-contaminated from other food products []. In addition, these consumers may also need to be attentive to the type of plant-based milk alternative they consume, as those reporting cow milk allergies are often allergic to soy proteins as well [].

Reportedly, consumers belonging to the Millennial and Generation Z generational cohorts are consuming plant-based milk alternatives as a values-based reflection [,,]. Other plant-based milk consumers include those who distrust dairy-based milk due to health and food safety concerns [,]. Possible food safety concerns could be heightened by scandals such as antibiotic-resistant pathogens transmitted to human beings through dairy milk consumption [].

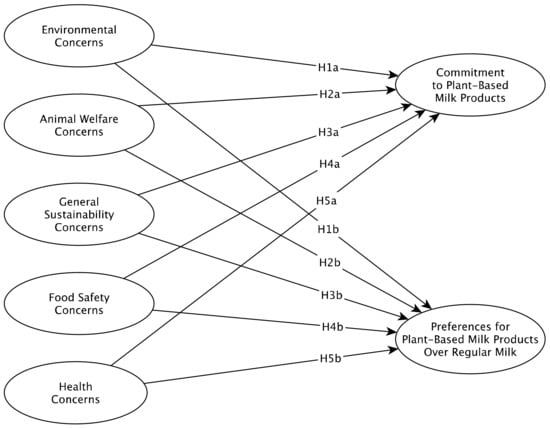

Overall, in US food retail, product assortments of plant-based milk alternatives are steadily increasing. Compared to the 2013 figures, plant-based milk alternatives increased from 1.2 kg per person to 2.7 kg in 2022 []. Leading the milk alternative varieties for US consumers are almond, oat, and soy. [,] The market value of these beverages is more than 9 billion USD []. Plant-based milk alternatives are slowly replacing dairy milk as a staple food item in many US households, and plant-based milk alternatives are purchased in higher quantities than any other plant-based food items [,]. Given the importance of plant-based milk alternatives in consumers’ everyday lives, it needs to be acknowledged that recent research at the nexus of plant-based milk alternatives and consumer behavior is small but developing. The focus of plant-based milk alternative research has primarily been to investigate the drivers of willingness to try and willingness to pay as consumer behaviors requiring a low to medium involvement. Further, these studies have examined the issues from the perspectives of attribute preferences, brand image, and consumer segmentation [,,,,]. The specific aspects of consumer commitment to and preferences for plant-based milk products over regular animal-based products have not been as widely explored. Recent studies have called for a finer-grained understanding of how health, sustainability, and other value-based motives drive this consumer behavior. Hence, the current study combines both aspects and is filling both gaps, understanding higher-ordered consumer behaviors and combining the salient predictors driving these behaviors into one model. From a food marketing perspective, understanding preference and commitment is relevant, as this facilitates the crafting of marketing strategies that lead to repeat purchases. Aligned with the literature review on behavioral predictors, hypotheses and a proposed conceptual model have been developed (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Proposed conceptual model.

2. Literature Review and Conceptual Model

Understanding consumer behavior and the concerns impacting their buying behavior and commitment is essential, as milk and milk-based product consumption are not always clear-cut []. A recent study on plant-based milk alternatives and animal-based milk found that a majority of consumers are actually “combination consumers” who drink both types of milk []. Given that all consumers, regardless of their market segment, demand transparent product information and verification, in particular value-based information regarding healthiness, environmental friendliness, and sustainability, such product information may encourage consumers to switch to another product and build their commitment elsewhere []. Therefore, the following literature review is dedicated to healthiness, food safety, environmental friendliness, animal welfare, and sustainability as important predictors. This review borrows from studies focusing on plant-based meat products when studies on milk-based products are absent. This is deemed appropriate due to the similar nature of both substitute products.

2.1. Environmental Concerns

Various studies have been dedicated to plant-based food and beverages and environmentally responsible consumerism [,,]. These studies have shown that plant-based milk beverages and other milk-based products, such as yogurt, cheese, and ice cream, are appreciated by consumers, as these products are offered as more environmentally friendly alternatives []. Regular milk and milk-based products have been criticized, as the production and processing of these products are associated with deforestation and high carbon and water footprints, resulting from greenhouse gas emissions and water pollution [,]. Environmentally responsible consumers are aiming to reduce their impact on the environment through their product choices and buying behavior [,]. As these consumers are knowledgeable about environmental issues and have positive attitudes towards environmentally friendly product alternatives, they demand transparency and verification concerning production processes []. Therefore, the following hypotheses are proposed:

Hypothesis H1a.

Environmental concerns positively impact consumers’ commitment to plant-based milk products.

Hypothesis H1b.

Environmental concerns positively impact consumers’ preferences for plant-based milk products over regular milk products.

2.2. Animal Welfare Concerns

Animal welfare has been widely discussed in the US dairy industry, media, and a plethora of academic studies. Agricultural consumer studies have indicated that the practices of dairy farms are raising consumer concerns and criticisms [,,,]. These include inappropriate flooring and pasture access, separating calves from their mothers too early, the quality of neonatal care, and dehorning or tail docking without anesthesia [,,]. Animal welfare certification has been employed to verify the appropriate on-farm production practices and counteract information asymmetry []. This is important because consumers require information about on-farm welfare and often feel sympathy for or are driven by altruistic values towards farm animals []. Since animal cruelty and the inappropriate treatment of farm animals are the main reasons for product switching or refusing milk consumption, the following hypotheses are proposed:

Hypothesis H2a.

Animal welfare concerns positively impact consumers’ commitment to plant-based milk products.

Hypothesis H2b.

Animal welfare concerns positively impact consumers’ preferences for plant-based milk products over regular milk products.

2.3. General Sustainability Concerns

Sustainability-conscious consumers consider the social, environmental, and economic impacts of their consumption choices []. These consumers recognize the requirement of balancing their own needs and wants with those of wider society []. Various studies have been dedicated to consumer behavior and concerns, and the extant literature has addressed individual-related factors, including beliefs, attitudes, and values as predictors for sustainable behavior. Increasing consumer concerns are reflected in the growing popularity of products with sustainability certifications and the support for brands and businesses involved in social and environmental activities []. While product- and consumption-specific sustainability concerns are likely to have the largest impact on the consumer attitudes and behaviors toward those products, there is support to suggest that concerns about the effect of the non-specific sustainability of production processes and practices on the planet and people, especially those impacting present and future generations, are also likely to have an impact [,,]. Amidst this background, the following hypotheses are proposed:

Hypothesis H3a.

General sustainability concerns positively impact consumers’ commitment to plant-based milk products.

Hypothesis H3b.

General sustainability concerns positively impact consumers’ preferences for plant-based milk products over regular milk products.

2.4. Food Safety and Health Concerns

Studies on plant-based food and beverages have emphasized health-related consumer trends and the importance of food safety as a basic consumer right []. In this context, Aschemann-Witzel et al., (2021) emphasized “freedom foods”, as they allow consumers to minimize their worries for people, animals, the environment, their health, and their safety []. Following Rizzo et al., (2023), concerns about health are equally as important to consumers as ethical and value-based reasons. Their study emphasized that socio-demographic characteristics, such as gender and a high income, as well as consumption preferences such as eating organic food and other health-related issues, impact consumers’ decisions to substitute plant-based alternatives for traditional foods []. The impact on human health and associated costs are the main drivers for consumers moving toward plant-based diets [], though most plant-based milk products reportedly lack the nutritional balance found in regular milk products [,,]. Other product reservations are additives and unfamiliar ingredients, particularly in plant-based milk blends []. Regardless, the consumer appeal of plant-based milk products is based on their functionally active components with health-promoting properties and minimized exposure to zoonosis [,]. In addition, plant-based milk products contain no lactose or cholesterol [,,,,]. Therefore, the following hypotheses are proposed:

Hypothesis H4a.

Food safety concerns positively impact consumers’ commitment to plant-based milk products.

Hypothesis H4b.

Food safety concerns positively impact consumers’ preferences for plant-based milk products over regular milk products.

Hypothesis H5a.

Health concerns positively impact consumers’ commitment to plant-based milk products.

Hypothesis H5b.

Health concerns positively impact consumers’ preferences for plant-based milk products over regular milk products.

The conceptual model builds on the literature discussed (Figure 1). The model proposes that U.S. consumers’ preferences for plant-based milk products over regular animal-based products and their commitment to plant-based milk products are impacted by concerns about the environment, animal welfare, sustainability, and health.

3. Materials and Methods

The data collection was facilitated through the online data collection tool Qualtrics. Data from 486 US consumers were collected in December 2022. Participation in the survey required the respondents to reside in the US, be consumers of plant-based milk alternatives, and be 18 years of age. The survey participants who were registered workers received access to the survey on Amazon Mechanical Turk (Mturk)—a widely used crowdsourcing platform [,,]. Pre-testing of the online survey was carried out with fifteen Mturk workers. The pre-testing allowed us to improve the instructions, survey items, scales, survey setup, and estimate the average survey completion time. The pre-testing helped to assure a positive experience for the researchers and survey participants, as such improvements reportedly reduced the frustration of the Mturk workers [,]. Initially, 500 US consumers completed the online survey, however, 14 survey responses were omitted. These responses were incomplete and were associated with survey speeding behavior [], being well below the average completion time of 15 min. Even this reduced sample size (486) was deemed as appropriate for exploring the predictors of preferences for and commitment to plant-based milk alternatives over animal-based milk. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) was also used. Following Hair et al. (2022), we used their ten-times rule used to determine the minimum sample size, which, in this case, was a minimum of 50 [].

The survey included items measuring socio-demographics, concerns surrounding animal welfare environment, sustainability, health, and food safety, and commitment to plant-based milk alternatives. The questions used closed-ended seven-point Likert agreement scales. Preference for plant-based milk products over regular milk products was measured on a 1 to 100 sliding scale. The items were adapted from the plant-based substitute product literature [,,,].

The data analysis was executed in consecutive steps. The descriptive statistics explaining the background profiles of the consumers were generated with SPSS 28. This was followed by the PLS-SEM analysis, which was conducted with SmartPLS 4. PLS-SEM is an effective method for complex explorative models and requires assessing a measurement model analysis followed by a structural model analysis []. The PLS-SEM approach does not require a normal distribution of data and allows for the inclusion of formative or higher-order constructs.

Reliability and validity checks are the underlying foundation of the measurement model. Hair et al. (2022) contended that the measurement model comprises assessments of item/scale factor loadings (>0.4) for scale item/scale contribution [], Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability (>0.6) for scale reliability [,], and the average variance extracted (>0.6) for scale convergence []. Discriminant validity was tested using the Heterotrait–Monotrait criterion (<0.9) and the Fornell–Larker criterion (diagonal > cross-loadings) [,]. Finally, the presence of problematic multicollinearity, which could also be an indication that the model was contaminated by common method bias, was tested using Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) (<3.3) [,].

Then, the structural model was examined, and ultimately the hypotheses were tested. This analysis used 5000 bootstrapping test samples to establish path significance []. In addition, 5 model performance checks were performed, including overall goodness of fit; normed fit index (NFI) (greater = better); standardized root mean square residual (<0.08 = good, >0.1 problematic); explanatory power (R2), which was small (near 0.25), moderate (near 0.5), and large (near 0.75); and predictive relevance (Q2), which was acceptable (>0), medium (>0.25), and strong (>0.5) [,].

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. US Consumers’ Socio-Demographic Profile

The demographics of the surveyed US consumers are displayed in Table 1. In terms of gender representation, 51% of the surveyed consumers identified as female and 49% as male. The largest frequency of consumers was in the age range of 25–44 years old and held a university degree. Household income was from 25,000 to 75,000 USD. Overall, the sample can be described as comparatively younger, better educated, and earning less than the census averages. For comparisons concerning the US population, information from the most recent census is displayed in Table 1.

Table 1.

US consumers’ socio-demographic profiles.

4.2. Measurement Model Results

Table 2 shows the measurement model results, where all the values can be described as appropriate. This includes the Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability indicators confirming the construct reliability. In addition, the average variance extracted values and factor loadings of all the items were above their required threshold values, indicating a good item-scale convergent validity []. Table 3 shows that discriminant validity was confirmed for all the constructs across both criterion tests []. Finally, the VIF scores indicate that the model did not have problematic multicollinearity and it can also be considered as free from common method bias [,].

Table 2.

Scale loadings, reliabilities, and convergent validity for multi-item scales.

Table 3.

Scale discriminant validity.

4.3. Structural Model Results

The structural model required confirmation of the goodness of fit, explanatory power, and predictive relevance. The model had a normal fit index (NFI) of 0.704, a standardized root means square residual (SRMR) of 0.089, and an overall goodness of fit (GoF) of 0.540, indicating an adequate model fit. The model’s explanatory power was moderate, with the model’s constructs contributing to an R2 of 0.540 or 54% of the variance for commitment to plant-based milk alternatives, and 0.342 or 34.2% of the preference for plant-based milk products over regular milk products. This indicates that the model could explain consumer behavior requiring no (preference for plant-based over regular milk) and high commitment (commitment to milk alternatives) alike, but appeared to be overall better suited to higher commitment behaviors. Predictive relevance was confirmed with all Q2 values higher than zero, and an average Q2 score of 0.423 suggested that the predictive relevance of the model was moderate to strong.

4.4. Hypothesis Testing Results

Animal welfare significantly impacted commitment to plant-based milk products, indicating support for hypothesis H1a, however, it did not significantly impact preference for plant-based milk products, indicating no support for hypothesis H1b. Additionally, hypotheses H2a and H2b found support, as environmental and food safety concerns significantly impacted the U.S. consumers’ preferences for plant-based milk products over regular milk products, as well as their commitment to plant-based milk products. Surprisingly, H3a and H3b were found to be significant and negative, indicating that those with only general sustainability concerns were less likely to prefer and be committed to plant-based milk products. Finally, health and sustainability concerns significantly impacted the U.S. consumers’ preferences for plant-based milk products over regular milk, as well as their commitment to plant-based milk products. This indicates support for hypotheses H4a, H4b, H5a, and H5b (See Table 4).

Table 4.

Results of hypothesis testing.

5. Discussion

The current study was dedicated to understanding the predictors for U.S. consumers’ commitment to plant-based milk alternatives and consumers’ preferences for plant-based milk products over regular milk products. Overall, the conceptual model was of an appropriate fit, with a moderate explanatory power and a strong predictive relevance. The results emphasized environmental concerns, food safety, and health for both types of consumer behavior, while animal welfare concerns were only relevant for commitment to plant-based milk. Furthermore, general sustainability concerns had a negative influence on higher-level commitment and preference for plant-based milk.

The results related to environmental concerns appeared to be confirmatory with one branch of the extant literature. These studies on plant-based diets have shown that environmental concerns impact the perceived value of food and beverages, and, respectively, consumer choices and commitment. Consumer attitudes towards and concerns for the environment are relevant predictors for consumer satisfaction and product commitment. Moreira et al. (2023) emphasized moral and environmental reasons as the main reasons for commitment to plant-based beverages []. However, other studies have not found environmental concerns to be a significant predictor of consumers’ dietary behavior in the context of plant-based food alternatives. Alae-Carew et al. (2022) emphasized that environmental aspects are relevant to many consumers, and some desire a “hassle free” substitution. Other consumers may not be aware of these environmental aspects, hence, the authors called for a clarification of the health and environmental impacts of plant-based food options []. When discussing plant-based milk alternatives and environmental friendliness, the aspects of ultra-processing and additional energy use are often not taken into account [,,].

Country context, product focus, and choices related to the conceptual framework may explain the inconclusiveness of the literature and the stronger alignment with the first branch of the literature, which is dedicated to consumer behavior requiring a high commitment. Interestingly, the findings related to sustainability seemed to contradict what was found with the environmental concerns results. Concern for general sustainability issues was found to inhibit higher-level commitment to and preferences for plant-based milk substitutes. Perhaps this confirms that sustainability and environmental concerns and their impacts on consumer behavior are multifaceted, personal, and complex. Another possible explanation is the mismatch between non-specific concerns and higher commitment. Perhaps general concerns would be more of a positive influence on lower levels of commitment, such as willingness to try and willingness to buy.

The results related to health concerns can be explained by the fact that the extent of consumers’ health consciousness impacts their food choices. Kemper (2020), Bakr et al. (2022), and Rizzo et al. (2023) emphasized that, in the context of plant-based diets, health concerns are an important consumer motive [,,,]. Lim et al. (2021) and Chang et al. (2021) found that health is a major factor driving loyalty toward businesses selling plant-based food and beverages [,].

Food safety and commitment to plant-based food products have not been widely studied in a plant-based food and beverage context. However, marketing studies dedicated to fruit, meat, and fish have indicated that country or place of origin and trust in certification allow consumers to infer food safety and quality, as the underlying foundation of choices in favor of plant-based products and, respectively, commitment to them [].

6. Conclusions

The present study makes a theoretical contribution to the extant literature on consumer behavior in the context of plant-based milk products. Previous studies have largely been focused on single and dual predictors and behaviors requiring lower levels of consumer commitment, such as willingness to try or willingness to buy. As the present study was focused on product commitment and preference for plant-based milk products over regular ones, using multiple competing predictors, the study presented a more comprehensive picture of the factors driving these behaviors. The results provide insights for marketing managers in U.S. food retail chains. Understanding this more complete picture of commitment is relevant for developing loyalty programs, attempts to encourage sustainable consumption, and guarding against product/brand switching. The latter is currently of importance, as the US food market is experiencing a prolonged recession and food price inflation.

Marketers may find it useful to use a customer-centric marketing approach, implementing strategies that aim to exceed consumers’ needs and wants and fuel consumer loyalty. Value marketing campaigns involve customers to co-create product and services promotion with their positive recommendations and reviews []. To achieve this, emphasizing environmental friendliness and food safety may be useful, as these were the strongest predictors of both behaviors. Despite marketers making sustainability claims, they need to avoid overstating the importance of certain product attributes if they are not demonstrably better than regular animal-based milk products. For example, ultra-processing may diminish some health advantages, and some nut-based milks such as almond milk have high water footprints [,]. These suggestions are grounded in earlier consumer research on green marketing, acknowledging the benefit of marketing a product as sustainable. However, consumers may doubt the truthfulness of these claims and whether green products offer meaningful improvements over non-sustainable products []. A successful campaign should address altruistic and instrumental values as the underlying foundation of all the factors investigated and acknowledged in this study. In addition, it recommended to address specific sustainability aspects, as the present and previous research shows that consumers are distinctive with respect to sustainability claims. Simplified but specific enough messaging may allow business to set themselves apart [].

In terms of limitations, the present study was based on a consumer sample from a crowdsourcing platform. These kinds of samples are often limited in their representation compared to studies using samples with quotas based on census statistics, thus mirroring the US population. Notwithstanding, Mturk samples have proven to be superior to samples using participants recruited on college campuses or via social media platforms. Another limitation is that only plant-based milk consumers were involved in the study, and including the perspectives of consumers without plant-based milk experience would have been of value to the study. Hence, future studies could continue in several directions, including focusing on specific consumers, such as those that purchase both plant-based and regular products. This would enable a study of the factors that influence product switching behavior or the potential triggers that alter the preferences for one product or anther across contexts, e.g., eating at home and eating out. Further studies could investigate word of mouth and social media discussions related to plant-based food and beverages as examples of “healthy” ultra-processed products. The generational cohorts of Gen Z and Millennials could be targeted, as these consumers tend to favor plant-based milk products [,]. As millennials often make product choices for their children, the consumption choices of parents for their children in health and nutritional contexts would be of value to explore. The investigation may extend the work of Shiano et al. (2022) [].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.R. and D.L.D.; methodology, M.R. and D.L.D.; software, M.R.; validation, M.R. and D.L.D.; formal analysis, M.R.; investigation, M.R. and D.L.D.; resources, M.R., D.L.D. and C.G.; data curation, D.L.D. writing—original draft preparation, M.R. and D.L.D.; writing—review and editing, M.R., D.L.D. and C.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the Human Ethics Committee at Lincoln University, New Zealand, in 2022 (HEC2022-49).

Informed Consent Statement

All participants gave their informed consent for inclusion before they participated in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the discussion and support provided by the Lincoln University Centre of Excellence in Transformative Agribusiness.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest in the context of this publication.

References

- Kemper, J.A.; Benson-Rea, M.; Young, J.; Seifert, M. Cutting down or eating up: Examining meat consumption, reduction, and sustainable food beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors. Food Qual. Prefer. 2023, 104, 104718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boukid, F. Plant-based meat analogues: From niche to mainstream. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2020, 247, 297–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bir, C.; Widmar, N.O.; Wolf, C.; Delgado, M.S. Traditional attributes moo-ve over for some consumer segments: Relative ranking of fluid milk attributes. Appetite 2018, 134, 162–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prescott, S.L.; D’adamo, C.R.; Holton, K.F.; Ortiz, S.; Overby, N.; Logan, A.C. Beyond Plants: The Ultra-Processing of Global Diets Is Harming the Health of People, Places, and Planet. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ares, G.; Alcaire, F.; Gugliucci, V.; Machín, L.; de León, C.; Natero, V.; Otterbring, T. Colorful candy, teen vibes and cool memes: Prevalence and content of Instagram posts featuring ultra-processed products targeted at adolescents. Eur. J. Mark. 2023, in press. [CrossRef]

- Craig, W.J.; Messina, V.; Rowland, I.; Frankowska, A.; Bradbury, J.; Smetana, S.; Medici, E. Plant-Based Dairy Alternatives Contribute to a Healthy and Sustainable Diet. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, R.; Schnepps, A.; Pichler, A.; Meixner, O. Cow milk versus plant-based milk substitutes: A comparison of product image and motivational structure of consumption. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slade, P.; Markevych, M. Killing the sacred dairy cow? Consumer preferences for plant-based milk alternatives. Agribusiness 2023, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, C.A.; Malone, T.; McFadden, B.R. Beverage milk consumption patterns in the United States: Who is substituting from dairy to plant-based beverages? J. Dairy Sci. 2020, 103, 11209–11217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montemurro, M.; Verni, M.; Rizzello, C.G.; Pontonio, E. Design of a Plant-Based Yogurt-Like Product Fortified with Hemp Flour: Formulation and Characterization. Foods 2023, 12, 485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.R.; Silva, M.M.; Ribeiro, B.D. Health issues and technological aspects of plant-based alternative milk. Food Res. Int. 2020, 131, 108972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alae-Carew, C.; Green, R.; Stewart, C.; Cook, B.; Dangour, A.D.; Scheelbeek, P.F. The role of plant-based alternative foods in sustainable and healthy food systems: Consumption trends in the UK. Sci. Total. Environ. 2022, 807, 151041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Padilla, E.; Faber, I.; Petersen, I.L.; Vargas-Bello-Pérez, E. Perceptions toward Plant-Based Milk Alternatives among Young Adult Consumers and Non-Consumers in Denmark: An Exploratory Study. Foods 2023, 12, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quintieri, L.; Fanelli, F.; Caputo, L. Antibiotic Resistant Pseudomonas spp. Spoilers in Fresh Dairy Products: An Underestimated Risk and the Control Strategies. Foods 2019, 8, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rombach, M.; Lucock, X.; Dean, D.L. No Cow? Understanding US Consumer Preferences for Plant-Based over Regular Milk-Based Products. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, S.; Goel, A.D.; Jain, V. Milk-borne diseases through the lens of one health. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1041051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista. U.S. Plant-Based Milks—Statistics & Facts. 2022. Available online: https://www.statista.com/topics/3072/us-plant-based-milks/#topicHeader__wrapper (accessed on 17 August 2023).

- Foodnavigator USA. Plant Based Milk by Numbers. US Retail: Oat Milk and Pea Milk Up in Double Digits, Almond Milk and Soy Milk Flat. Available online: https://www.foodnavigator-usa.com/Article/2022/07/25/Plant-based-milk-by-numbers-US-retail-Oat-milk-and-pea-milk-up-double-digits-almond-milk-and-soy-milk-flat (accessed on 17 August 2023).

- Ramsing, R.; Santo, R.; Kim, B.F.; Altema-Johnson, D.; Wooden, A.; Chang, K.B.; Semba, R.D.; Love, D.C. Dairy and Plant-Based Milks: Implications for Nutrition and Planetary Health. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, K.; Parker, M.; Ameerally, A.; Drake, S.; Drake, M. Drivers of choice for fluid milk versus plant-based alternatives: What are consumer perceptions of fluid milk? J. Dairy Sci. 2017, 100, 6125–6138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boaitey, A.; Minegishi, K. Determinants of Household Choice of Dairy and Plant-based Milk Alternatives: Evidence from a Field Survey. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2020, 26, 639–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardello, A.V.; Llobell, F.; Giacalone, D.; Chheang, S.L.; Jaeger, S.R. Consumer Preference Segments for Plant-Based Foods: The Role of Product Category. Foods 2022, 11, 3059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boaitey, A. Subjective Beliefs About Farm Animal Welfare Labels and Milk Anticonsumption. Food Ethics 2022, 7, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acquah, J.B.; Amissah, J.G.N.; Affrifah, N.S.; Wooster, T.J.; Danquah, A.O. Consumer perceptions of plant based beverages: The Ghanaian consumer’s perspective. Future Foods 2023, 7, 100229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammann, J.; Grande, A.; Inderbitzin, J.; Guggenbühl, B. Understanding Swiss consumption of plant-based alternatives to dairy products. Food Qual. Prefer. 2023, 110, 104947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tachie, C.; Nwachukwu, I.D.; Aryee, A.N.A. Trends and innovations in the formulation of plant-based foods. Food Prod. Process. Nutr. 2023, 5, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aschemann-Witzel, J.; Gantriis, R.F.; Fraga, P.; Perez-Cueto, F.J.A. Plant-based food and protein trend from a business perspective: Markets, consumers, and the challenges and opportunities in the future. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 61, 3119–3128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drigon, V.; Nicolle, L.; Fanny, G.H.; Gagnaire, V.; Arvisenet, G. Attitudes and beliefs of French consumers towards innovative food products that mix dairy and plant-based components. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2023, 32, 100725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlastelica, T.; Kostić-Stanković, M.; Rajić, T.; Krstić, J.; Obradović, T. Determinants of Young Adult Consumers’ Environmentally and Socially Responsible Apparel Consumption. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igarová, K.; Kádeková, Z.; Košičiarová, I.; Džupina, M.; Dvořák, M.; Smutka, L. Is Corporate Social Responsibility Considered a Marketing Tool? Case Study from Customers’ Point of View in the Slovak Food Market. Foods 2023, 12, 2770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Läpple, D.; Osawe, O.W. Concern for animals, other farmers, or oneself? Assessing farmers’ support for a policy to improve animal welfare. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2022, 105, 836–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mylan, J.; Morris, C.; Beech, E.; Geels, F.W. Rage against the regime: Niche-regime interactions in the societal embedding of plant-based milk. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2018, 31, 233–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ly, L.H.; Ryan, E.B.; Weary, D.M. Public attitudes toward dairy farm practices and technology related to milk production. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0250850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burton, M.; Eike, R. The Sustainability-Conscious Consumer: An Exploration of the Motivations, Values, Beliefs, and Norms Guiding Garment Life Extension Practices. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hempel, C.; Waldrop, M.; Roosen, J. Consumers’ perceptions of animal husbandry practices and their heterogeneous needs for information—Insights from a cross-country cluster analysis. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2023, 1, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolbe, K. Why milk consumption is the bigger problem: Ethical implications and deaths per calorie created of milk compared to meat production. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2018, 31, 467–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, S.U.; Chwialkowska, A.; Hussain, N.; Bhatti, W.A.; Luomala, H. Cross-cultural perspective on sustainable consumption: Implications for consumer motivations and promotion. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 25, 997–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, R.J.; Miranda, C.; Goñi, J. Empowering Sustainable Consumption by Giving Back to Consumers the ‘Right to Repair’. Sustainability 2020, 12, 850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, G.; Testa, R.; Dudinskaya, E.C.; Mandolesi, S.; Solfanelli, F.; Zanoli, R.; Schifani, G.; Migliore, G. Understanding the consumption of plant-based meat alternatives and the role of health-related aspects. A study of the Italian market. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2023, 32, 100690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sgroi, F.; Maenza, L.; Modica, F. Exploring consumer behavior and willingness to pay regarding sustainable wine certification. J. Agric. Food Res. 2023, 14, 100681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.J.; Rakib, N.; Min, J. An Exploration of Transformative Learning Applied to the Triple Bottom Line of Sustainability for Fashion Consumers. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torán-Pereg, P.; Mora, M.; Thomsen, M.; Palkova, Z.; Novoa, S.; Vázquez-Araújo, L. Understanding food sustainability from a consumer perspective: A cross cultural exploration. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2023, 31, 100646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astolfi, M.L.; Marconi, E.; Protano, C.; Canepari, S. Comparative elemental analysis of dairy milk and plant-based milk alternatives. Food Control 2020, 116, 107327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacalone, D.; Clausen, M.P.; Jaeger, S.R. Understanding barriers to consumption of plant-based foods and beverages: Insights from sensory and consumer science. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2022, 48, 100919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munekata, P.E.S.; Domínguez, R.; Budaraju, S.; Roselló-Soto, E.; Barba, F.J.; Mallikarjunan, K.; Roohinejad, S.; Lorenzo, J.M. Effect of Innovative Food Processing Technologies on the Physicochemical and Nutritional Properties and Quality of Non-Dairy Plant-Based Beverages. Foods 2020, 9, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paul, A.A.; Kumar, S.; Kumar, V.; Sharma, R. Milk Analog: Plant based alternatives to conventional milk, production, potential and health concerns. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 60, 3005–3023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydar, E.F.; Tutuncu, S.; Ozcelik, B. Plant-based milk substitutes: Bioactive compounds, conventional and novel processes, bioavailability studies, and health effects. J. Funct. Foods 2020, 70, 103975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, J.K.; Paolacci, G. Crowdsourcing Consumer Research. J. Consum. Res. 2017, 44, 196–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCredie, M.N.; Morey, L.C. Who Are the Turkers? A Characterization of MTurk Workers Using the Personality Assessment Inventory. Assessment 2017, 26, 759–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litman, L.; Robinson, J. Conducting Online Research on Amazon Mechanical Turk and Beyond; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Conrad, F. Speeding in Web Surveys: The tendency to answer very fast and its association with straightlining. Surv. Res. Methods 2014, 8, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.E.; Hult, G.T.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.A. Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 3rd ed.; Sage Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, A.C. The influence of perceived value and brand equity on loyalty intentions. The case of plant-based beverage consumers. Pol. J. Manag. Stud. 2023, 27, 96–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macdiarmid, J.I. The food system and climate change: Are plant-based diets becoming unhealthy and less environmentally sustainable? Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2021, 81, 162–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tulashie, S.K.; Amenakpor, J.; Atisey, S.; Odai, R.; Akpari, E.E.A. Production of coconut milk: A sustainable alternative plant-based milk. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 2022, 6, 100206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopplin, C.S.; Rausch, T.M. Above and beyond meat: The role of consumers’ dietary behavior for the purchase of plant-based food substitutes. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2021, 16, 1335–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhartanto, D.; Kartikasari, A.; Arsawan, I.W.E.; Suhaeni, T.; Anggraeni, T. Driving youngsters to be green: The case of plant-based food consumption in Indonesia. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 380, 135061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemper, J.A. Motivations, barriers, and strategies for meat reduction at different family lifecycle stages. Appetite 2020, 150, 104644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakr, Y.; Al-Bloushi, H.; Mostafa, M. Consumer intention to buy plant-based meat alternatives: A cross-cultural analysis. J. Int. Consum. Mark. 2022, 35, 420–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, K.A.; Ham, S.; Moon, H.Y.; Jang, Y.J.; Kim, C.S. How does food choice motives relate to subjective well-being and loyalty? A cross-cultural comparison of vegan restaurant customers in South Korea and Singapore. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2021, 25, 168–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.; Morrison, A.M.; Chen, Y.-L.; Chang, T.-Y.; Chen, D.Z.-Y. Does a healthy diet travel? Motivations, satisfaction and loyalty with plant-based food dining at destinations. Br. Food J. 2021, 123, 4155–4174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Psomas, E.L.; Bouranta, N.; Vouzas, F. The Effect of Service Recovery on Buying Intention—The role of perceived food safety. Int. J. Qual. Serv. Sci. 2017, 11, 69–86. [Google Scholar]

- Doyle, P. Value-based marketing. J. Strat. Mark. 2000, 8, 299–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, L.; Rosenthal, S. Signaling the green sell: The influence of eco-label source, argument specificity, and product involvement on consumer trust. J. Advert. 2014, 43, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiano, A.; Harwood, W.; Gerard, P.; Drake, M. Consumer perception of the sustainability of dairy products and plant-based dairy alternatives. J. Dairy Sci. 2020, 103, 11228–11243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schiano, A.; Nishku, S.; Racette, C.; Drake, M. Parents’ implicit perceptions of dairy milk and plant-based milk alternatives. J. Dairy Sci. 2022, 105, 4946–4960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).