Resilience and Sustainable Urban Tourism: Understanding Local Communities’ Perceptions after a Crisis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- What concepts or variables do residents perceive as being at the core of the COVID-19 pandemic’s main impacts on city tourism?

- What do residents expect their city’s tourism will look like in the future?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Sustainable Tourism Development and COVID-19 Pandemic’s Influence

Sustainability and resilience are two concepts that will allow … strategic functionality in urban planning, because whereas the first one prioritises results, the second one analyses processes, demonstrating that a partnership between these two concepts will allow for a widening of … [planners’] focus to anticipate anthropocentric and natural uncertainties.

2.2. COVID-19 Pandemic’s Impact on Local Communities

2.3. Resilience-Based Approach to COVID-19

[Resilience is] about adaptation, including building human resource capacities to change in efficient ways, creating learning institutions that can address changing circumstances while maintaining core values, understanding feedback loops in dynamic social and environmental systems and generally encouraging flexibility, creativity, and innovation in the culture of a community.

3. Materials and Methods

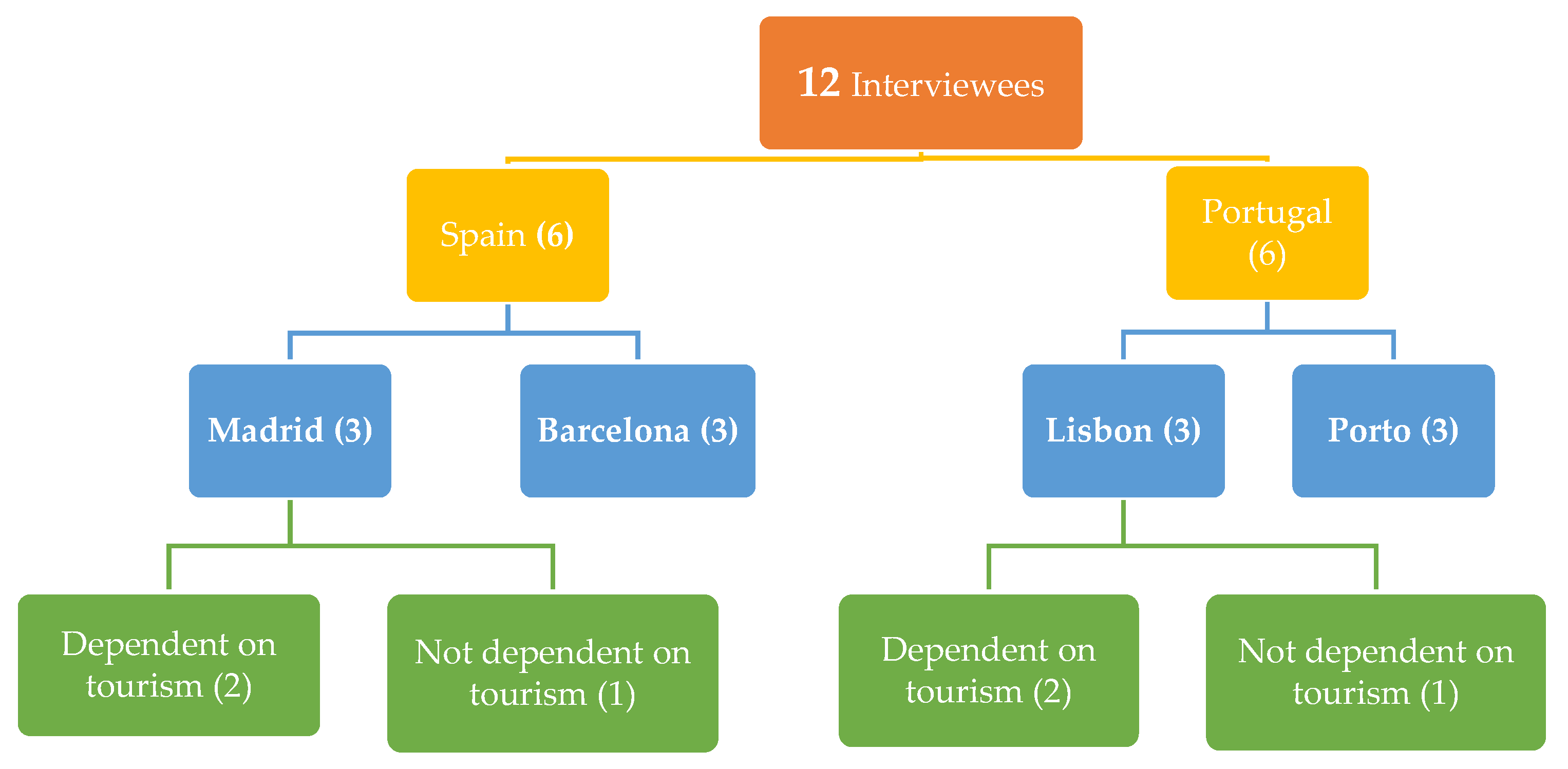

3.1. Research Context, Background, and Sampling Procedure

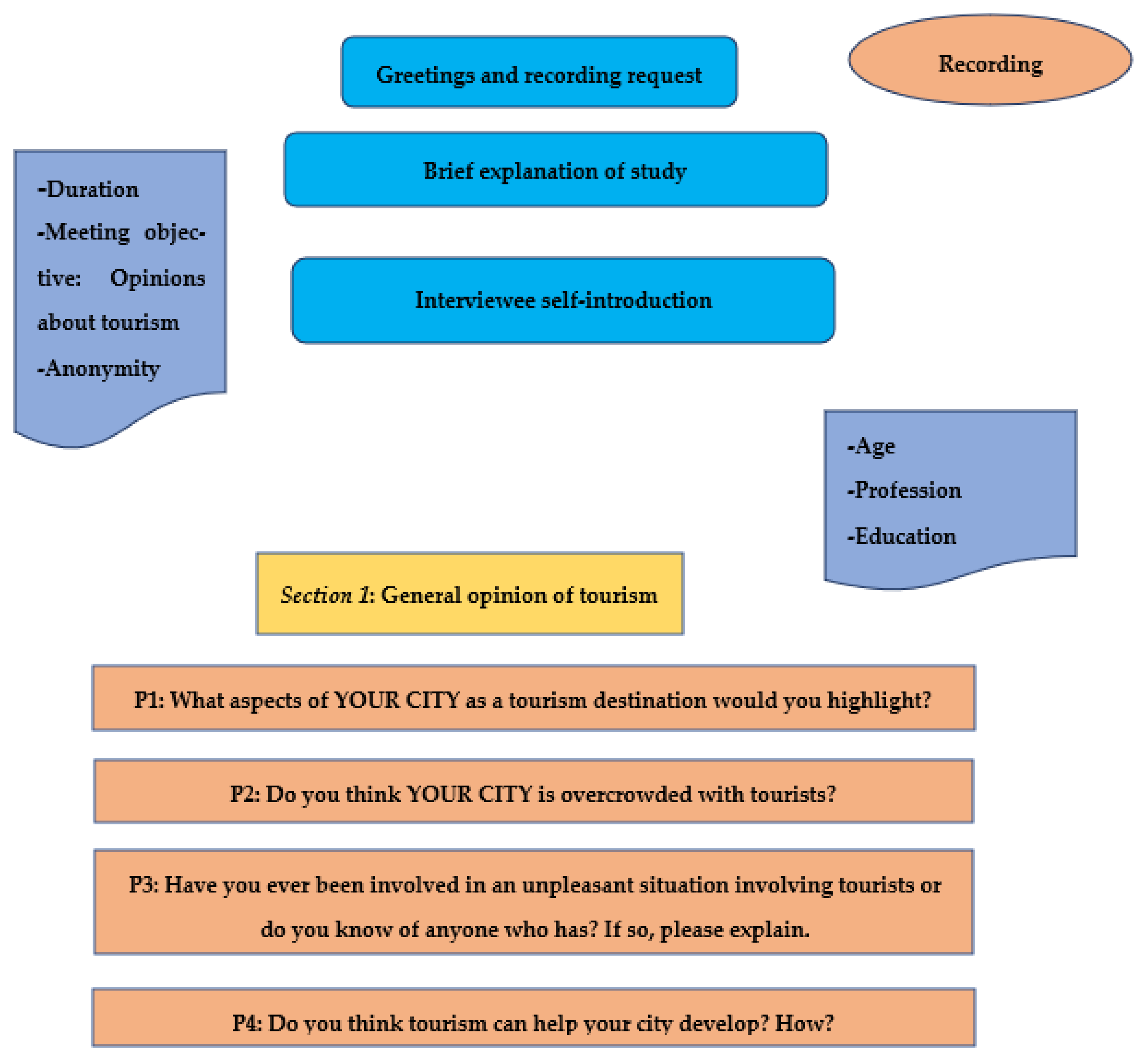

3.2. Research Design

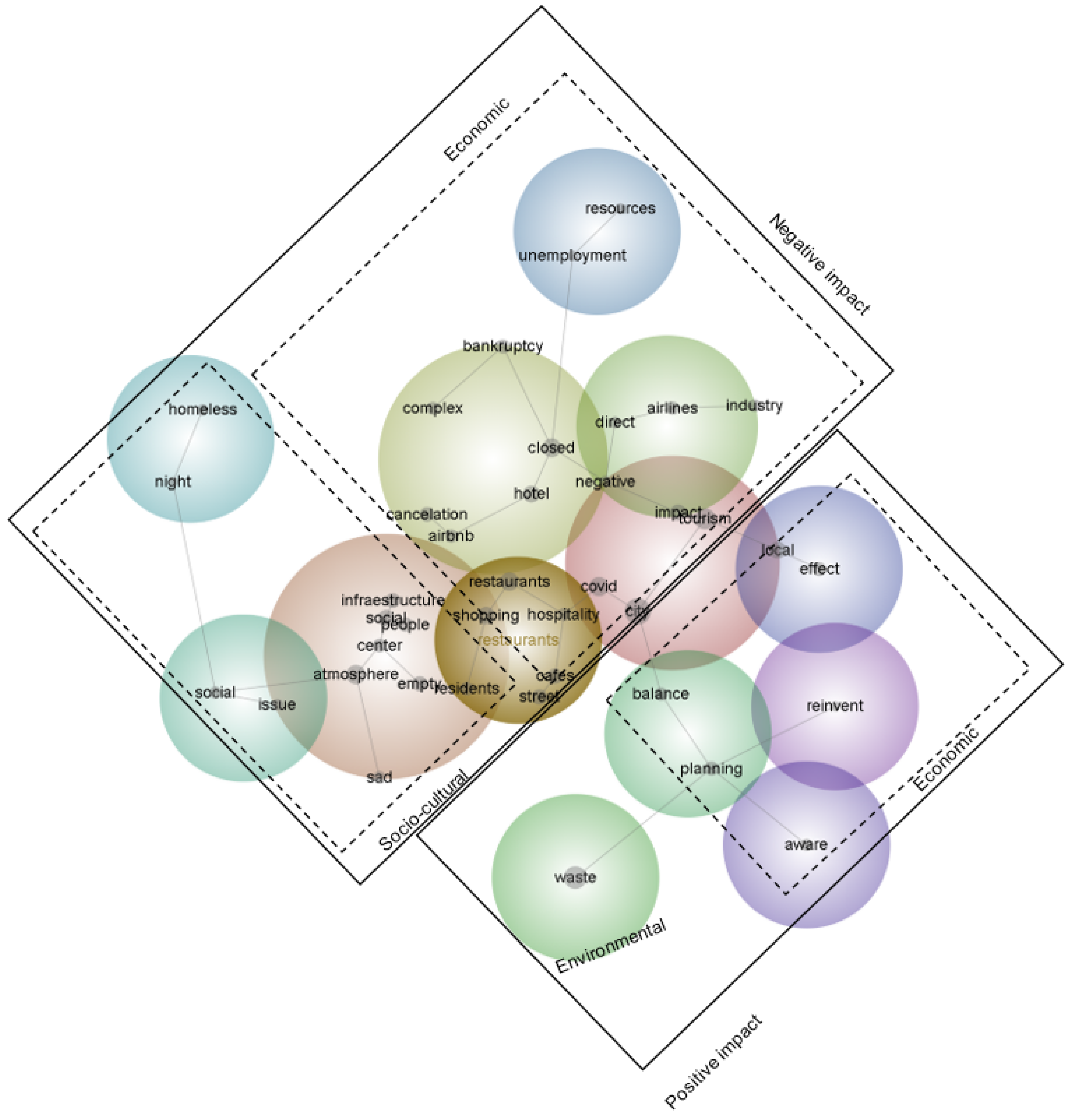

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Research Question One

[T]ourism planners think about the best way to move forward and correct what hasn’t been so good in the past. … One story that we heard concerned a local resident who wanted to continue living in the same historic, traditional area and [who couldn’t because of] tourists who wanted to experience living in an old Portuguese house.

4.2. Research Question Two

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

6.1. Theoretical Contributions

6.2. Practical Implications

6.3. Limitations and Avenues for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Interviewee | Dependent on Tourism | Age (Years) | Profession | Gender |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Madrid 1 | Yes | >30 | Hotel manager | Female |

| Madrid 2 | Yes | <30 | Hotel manager | Female |

| Madrid 3 | No | <30 | Biologist | Male |

| Barcelona 1 | Yes | >30 | Museum director | Male |

| Barcelona 2 | Yes | >30 | Restaurant manager | Male |

| Barcelona 3 | No | <30 | Communication director | Male |

| Lisbon 1 | No | >30 | Architect | Female |

| Lisbon 2 | Yes | >30 | Head of tourism division | Female |

| Lisbon 3 | No | >30 | Architect | Male |

| Porto 1 | Yes | >30 | Hotel manager | Female |

| Porto 2 | No | >30 | Senior social cohesion officer | Male |

| Porto 3 | Yes | <30 | Hotel manager | Female |

Appendix B

References

- Cheer, J.M. Human flourishing, tourism transformation and COVID-19: A conceptual touchstone. Tour. Geogr. 2020, 22, 514–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallego, I.; Font, X. Changes in air passenger demand as a result of the COVID-19 crisis: Using Big Data to inform tourism policy. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 29, 1470–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S.; Scott, D.; Hall, C.M. Pandemics, tourism and global change: A rapid assessment of COVID-19. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 29, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigala, M. Tourism and COVID-19: Impacts and implications for advancing and resetting industry and research. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 117, 312–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agovino, M.; Musella, G. Economic losses in tourism during the COVID-19 pandemic: The case of Sorrento. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 25, 3815–3839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prideaux, B.; Thompson, M.; Pabel, A. Lessons from COVID-19 can prepare global tourism for the economic transformation needed to combat climate change. Tour. Geogr. 2020, 22, 667–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mensah, E.A.; Boakye, K.A. Conceptualizing post-COVID 19 tourism recovery: A three-step framework. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2021, 20, 37–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wall, G. Beyond sustainable development. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2018, 43, 390–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burksiene, V.; Dvorak, J.; Burbulyte-Tsiskarishvili, G. Sustainability and sustainability marketing in competing for the title of European Capital of Culture. Organization 2018, 51, 66–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filimonau, V.; De Coteau, D. Tourism resilience in the context of integrated destination and disaster management (DM2). Int. J. Tour. Res. 2020, 22, 202–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lama, R.; Rai, A. Challenges in developing sustainable tourism post COVID-19 pandemic. In Tourism Destination Management in a Post-Pandemic Context; Gowreesunkar, V.G.B., Maingi, S.W., Roy, H., Micera, R., Eds.; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2021; pp. 233–244. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.; Park, M.; Lee, H.-S.; Ham, Y. Impact of demand-side response on community resilience: Focusing on a power grid after seismic hazards. J. Manag. Eng. 2020, 36, 04020071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, G.D.; Thomas, A.; Paul, J. Reviving tourism industry post-COVID-19: A resilience-based framework. Tour. Manag. Perspectives 2021, 37, 100786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheller, M. Reconstructing tourism in the Caribbean: Connecting pandemic recovery, climate resilience and sustainable tourism through mobility justice. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 29, 1436–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, K.S.; Li, L.-H. Understanding visitor–resident relations in overtourism: Developing resilience for sustainable tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 1197–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutcliffe, K.M.; Vogus, T. Organizing for resilience. In Positive Organizational Scholarship: Foundations of a New Discipline; Cameron, K.S., Dutton, J.E., Quinn, R.E., Eds.; Berrett-Koehler: San Franscisco, CA, USA, 2003; pp. 94–110. [Google Scholar]

- Coutu, D.L. How resilience works. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2002, 80, 46–56. [Google Scholar]

- Saarinen, J.; Gill, A.M. Tourism, resilience, and governance strategies in the transition towards sustainability. In Resilient Destinations and Tourism; Saarinen, J., Gill, A.M., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2018; pp. 15–33. [Google Scholar]

- Cheer, J.M.; Milano, C.; Novelli, M. Tourism and community resilience in the Anthropocene: Accentuating temporal overtourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 554–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sisneros-Kidd, A.M.; Monz, C.; Hausner, V.; Schmidt, J.; Clark, D. Nature-based tourism, resource dependence, and resilience of Arctic communities: Framing complex issues in a changing environment. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 1259–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romão, J. Tourism, smart specialisation, growth, and resilience. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 84, 102995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamaliah, M.M.; Powell, R.B. Ecotourism resilience to climate change in Dana Biosphere Reserve, Jordan. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 519–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriel-Campos, E.; Werner-Masters, K.; Cordova-Buiza, F.; Paucar-Caceres, A. Community eco-tourism in rural Peru: Resilience and adaptive capacities to the COVID-19 pandemic and climate change. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 48, 416–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, D.; Xu, W.; Lee, J.; Lee, C.-K. Residents’ perceived risk, emotional solidarity, and support for tourism amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Destination Mark. Manag. 2021, 19, 100553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, C.; Iba, W.; Clifton, J. Reimagining resilience: COVID-19 and marine tourism in Indonesia. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, R.T.; Park, J.; Li, S.; Song, H. Social costs of tourism during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 84, 102994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kańduła, S.; Przybylska, J. Financial instruments used by Polish municipalities in response to the first wave of COVID-19. Public Organ. Rev. 2021, 21, 665–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dvorak, J. Response of the Lithuanian municipalities to the First Wave of COVID-19. Baltic Reg. 2021, 13, 70–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenker, S.; Kock, F. The coronavirus pandemic—A critical discussion of a tourism research agenda. Tour. Manag. 2020, 81, 104164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Travel and Tourism Council. Available online: https://wttc.org/news-article/wttc-reveals-us-travel-tourism-sector-suffered-loss-of-766-billion-in-2020 (accessed on 15 July 2023).

- Wachyuni, S.S.; Kusumaningrum, D.A. The effect of COVID-19 pandemic: How are the future tourist behavior? J. Educ. Soc. Behav. Sci. 2020, 33, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamata, H. Tourist destination residents’ attitudes towards tourism during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 25, 134–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nian, S.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, J.; Li, D.; Wu, K.; Chen, X.; Yang, L. Two sides of a coin: A crisis response perspective on tourist community participation in a post-disaster environment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paunovic, I.; Müller, C.; Deimel, K. Citizen Participation for Sustainability and Resilience: A Generational Cohort Perspective on Community Brand Identity Perceptions and Development Priorities in a Rural Community. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robina-Ramírez, R.; Sánchez, M.S.-O.; Jiménez-Naranjo, H.V.; Castro-Serrano, J. Tourism governance during the COVID-19 pandemic crisis: A proposal for a sustainable model to restore the tourism industry. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 24, 6391–6412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedman, T.L. Our New Historical Divide: B.C. and A.C.—The World before Corona and the World after. The New York Times Online. 17 March 2020. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/17/opinion/coronavirus-trends.html (accessed on 15 June 2023).

- Ateljevic, I. Transforming the (tourism) world for good and (re)generating the potential ‘new normal’. Tour. Geogr. 2020, 22, 467–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, R.V.; de Man, F. Tourism, inclusive growth and decent work: A political economy critique. J. Sustain Tour. 2021, 29, 353–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.-L.; McAleer, M.; Ramos, V. A Charter for Sustainable Tourism after COVID-19. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, M.; Kizildag, M.; Croes, R. COVID-19 and small lodging establishments: A break-even calibration analysis (CBA) model. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 94, 102814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins-Desbiolles, F. Sustainable tourism: Sustaining tourism or something more? Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 25, 157–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, S.; Morgan, N. Tourism and Inequality: Problems and Prospects; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Cole, S.; Eriksson, J. Tourism and human rights. In Tourism and Inequality: Problems and Prospects; Cole, S., Morgan, N., Eds.; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2010; pp. 107–125. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins-Desbiolles, F.; Carnicelli, S.; Krolikowski, C.; Wijesinghe, G.; Boluk, K. Degrowing tourism: Rethinking tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 1926–1944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igarza, L.M.Z.; Guisado, R.O.; Campdesuñer, R.P.; González, L.G.C. Perspectivas sostenibles del desarrollo: Integración de la resiliencia a la ordenación urbana. Avances 2019, 21, 394–404. [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez Lopez, L.J.; Grijalba Castro, A.I. Sustainability and Resilience in Smart City Planning: A Review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Dong, Y.; Liu, Z. A review of social-ecological system resilience: Mechanism, assessment and management. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 723, 138113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haleem, A.; Javaid, M.; Vaishya, R.; Deshmukh, S.G. Areas of academic research with the impact of COVID-19. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2020, 38, 1524–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins-Desbiolles, F. The ‘war over tourism’: Challenges to sustainable tourism in the tourism academy after COVID-19. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 29, 551–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romagosa, F. The COVID-19 crisis: Opportunities for sustainable and proximity tourism. Tour. Geogr. 2020, 22, 690–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro Jurado, E.; Ortega Palomo, G.; Torres Bernier, E. Propuestas de Reflexion Desde el Turismo Frente al COVID-19. Instituto Universitario de Investigación de Inteligencia e Innovación Turística de la Universidad de Málaga. Available online: https://www.i3t.uma.es/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Propuestas-Reflexiones-Turismo-ImpactoCOVID_i3tUMA.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2023).

- Diaz-Soria, I. Being a tourist as a chosen experience in a proximity destination. Tour. Geogr. 2017, 19, 96–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeuring, J.H.G.; Haartsen, T. The challenge of proximity: The (un)attractiveness of near-home tourism destinations. Tour. Geogr. 2017, 19, 118–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, L.; Forsyth, P.; Spurr, R. Tourism economics and policy analysis: Contributions and legacy of the Sustainable Tourism Cooperative Research Centre. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2016, 26, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muley, D.; Shahin, M.; Dias, C.; Abdullah, M. Role of Transport during Outbreak of Infectious Diseases: Evidence from the Past. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paunović, I.; Dressler, M.; Mamula Nikolić, T.; Popović Pantić, S. Developing a competitive and sustainable destination of the future: Clusters and predictors of successful national-level destination governance across destination life-cycle. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida-García, F.; Pelaez-Fernandez, M.A.; Balbuena-Vazquez, A.; Cortés-Macias, R. Residents’ perceptions of tourism development in Benalmádena (Spain). Tour. Manag. 2016, 54, 259–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garau-Vadell, J.B.; Gutierrez-Taño, D.; Diaz-Armas, R. Economic crisis and residents’ perception of the impacts of tourism in mass tourism destinations. J. Dest. Mark. Manag. 2018, 7, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Sanchez, A.; Porras-Bueno, N.; de los Ángeles Plaza-Mejía, M. Explaining residents’ attitudes to tourism: Is a universal model possible? Ann. Tour. Res. 2011, 38, 460–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yang, L.; Shen, H.; Wu, Z. Modeling intra-destination travel behavior of tourists through spatio-temporal analysis. J. Dest. Mark. Manag. 2019, 11, 260–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.H.; Jan, F.H. Can community-based tourism contribute to sustainable development?: Evidence from residents’ perceptions of the sustainability. Tour. Manag. 2019, 70, 368–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, D.B.; Moyle, B.; McLennan, C.-I.J. The citizen within: Positioning local residents for sustainable tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2022, 30, 897–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozturk, A.B.; Ozer, O.; Çaliskan, U. The relationship between local residents’ perceptions of tourism and their happiness: A case of Kusadasi, Turkey. Tour. Rev. 2015, 70, 232–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Jaafar, M.; Ramayah, T. Urban vs. rural destinations: Residents’ perceptions, community participation and support for tourism development. Tour. Manag. 2017, 60, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Jaafar, M. Residents’ perception toward tourism development: A pre-development perspective. J. Place Manag. Devel. 2016, 9, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Uysal, M.; Sirgy, M.J. How does tourism in a community impact the quality of life of community residents? Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 527–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cottrell, S.P.; Vaske, J.J.; Roemer, J.M. Resident satisfaction with sustainable tourism: The case of Frankenwald Nature Park, Germany. Tour. Manag. Perspectives 2013, 8, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andereck, K.L.; Valentine, K.M.; Knopf, R.C.; Vogt, C.A. Residents’ perceptions of community tourism impacts. Ann. Tour. Res. 2005, 32, 1056–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bujosa, A.; Rosselló, J. Climate change and summer mass tourism: The case of Spanish domestic tourism. Clim. Change 2013, 117, 363–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, D.W.; Stewart, W.P. A structural equation model of residents’ attitudes for tourism development. Tour. Manag. 2002, 23, 521–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postma, A.; Schmuecker, D. Understanding and overcoming negative impacts of tourism in city destinations: Conceptual model and strategic framework. J. Tour. Futures 2017, 3, 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Jaafar, M.; Kock, N.; Ramayah, T. A revised framework of social exchange theory to investigate the factors influencing residents’ perceptions. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2015, 16, 335–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hateftabar, F.; Chapuis, J.M. How resident perception of economic crisis influences their perception of tourism. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 43, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gursoy, D.; Chi, C.G. Effects of COVID-19 pandemic on hospitality industry: Review of the current situations and a research agenda. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2020, 29, 527–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahabi Sorman Abadi, R.; Ghaderi, Z.; Hall, C.M.; Soltaninasab, M.; Hossein Qezelbash, A. COVID-19 and the travel behavior of xenophobic tourists. J. Policy Res. Tour. Leis. Events 2021, 15, 377–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeji, T.; Nagai, H. Residents’ attitudes towards peer-to-peer accommodations in Japan: Exploring hidden influences from intergroup biases. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2021, 18, 491–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontoura, L.M.; Lusby, C.; Romagosa, F. Post-COVID-19 tourism: Perspectives for sustainable tourism in Brazil, USA and Spain. Rev. Acad. Obs. Inov. Tur. 2020, 14, 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Xu, H.; Lew, A.A. Livelihood resilience in tourism communities: The role of human agency. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 606–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCartney, G.; Pinto, J.; Liu, M. City resilience and recovery from COVID-19: The case of Macao. Cities 2021, 112, 103130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adger, W.N. Social and ecological resilience: Are they related? Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2000, 24, 347–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobierno de España; Informe Annual; Instituto Nacional de Estadística: Madrid, Spain, 2020.

- Tourismo de Portugal. Visão Geral. Turismo de Portugal. Available online: http://www.turismodeportugal.pt/pt/Turismo_Portugal/visao_geral/Paginas/default.aspx (accessed on 15 June 2023).

- Ferrer-Rosell, B.; Martin-Fuentes, E.; Marine-Roig, E. Diverse and emotional: Facebook content strategies by Spanish hotels. Inf. Tech. Tour. 2020, 22, 53–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional de Estatistica. Estatísticas Territoriais. Available online: https://www.ine.pt/xportal/xmain?xpid=INE&xpgid=ine_unid_territorial&menuBOUI=13707095&contexto=ut&selTab=tab3 (accessed on 8 February 2021).

- Creswell, J.W.; Poth, C.N. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches; Sage: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Jarness, V. Viewpoints and points of view: Situating symbolic boundary drawing in social space. Eur. Soc. 2018, 20, 503–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Creswell, J.D. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches; Sage: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Conceptual and design thinking for thematic analysis. Qual. Psychol. 2022, 9, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fugard, A.J.; Potts, H.W. Supporting thinking on sample sizes for thematic analyses: A quantitative tool. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2015, 18, 669–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morse, J.M. The significance of saturation. Qual. Health Res. 1995, 5, 147–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshin, A.; Brochado, A.; Rodrigues, H. Halal tourism is traveling fast: Community perceptions and implications. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2020, 18, 100503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.-Y.; Wall, G.; Pearce, P.L. Shopping experiences: International tourists in Beijing’s Silk Market. Tour. Manag. 2014, 41, 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harwood, I.A.; Gapp, R.P.; Stewart, H.J. Cross-check for completeness: Exploring a novel use of Leximancer in a grounded theory study. Qual. Rep. 2015, 20, 1029–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunne, C. The place of the literature review in grounded theory research. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2011, 14, 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohajan, D.; Mohajan, H. Glaserian grounded theory and Straussian grounded theory: Two standard qualitative research approaches in social science. J. Econ. Dev. Environ. People 2023, 12, 72–81. [Google Scholar]

- Brochado, A.; Rita, P.; Oliveira, C.; Oliveira, F. Airline passengers’ perceptions of service quality: Themes in online reviews. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 31, 855–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tkaczynski, A.; Rundle-Thiele, S.R.; Cretchley, J. A vacationer-driven approach to understand destination image: A Leximancer study. J. Vacat. Mark. 2015, 21, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rather, R.A. Monitoring the impacts of tourism-based social media, risk perception and fear on tourist’s attitude and revisiting behaviour in the wake of COVID-19 pandemic. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 3275–3283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, S.-S. Tourism recovery strategy against COVID-19 pandemic. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2020, 46, 188–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannides, D.; Gyimóthy, S. The COVID-19 crisis as an opportunity for escaping the unsustainable global tourism path. Tour. Geogr. 2020, 22, 624–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M.; Scott, D.; Gössling, S. Pandemics, transformations and tourism: Be careful what you wish for. Tour. Geogr. 2020, 22, 577–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novotny, A.; Dávid, L.; Csáfor, H. Applying RFID technology in the retail industry—Benefits and concerns from the consumer’s perspective. Amfiteatru Econ. J. 2015, 17, 615–631. [Google Scholar]

- Sigala, M. New technologies in tourism: From multi-disciplinary to anti-disciplinary advances and trajectories. Tour. Manag. Perspectives 2018, 25, 151–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Đikanović, Z.; Jakšić-Stojanović, A. The implementation of new technologies in tourism and hospitality industry—Practices and challenges. In New Technologies, Development and Application V; Karabegović, I., Kovačević, A., Mandžuka, S., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 991–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, S.; Dillette, A.; Alderman, D.H. ‘We can’t return to normal’: Committing to tourism equity in the post-pandemic age. Tour. Geogr. 2020, 22, 476–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stankov, U.; Filimonau, V.; Vujičić, M.D. A mindful shift: An opportunity for mindfulness-driven tourism in a post-pandemic world. Tour. Geogr. 2020, 22, 703–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assaf, A.; Scuderi, R. COVID-19 and the recovery of the tourism industry. Tour. Econ. 2020, 26, 731–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.; Kozak, M.; Yang, S.; Liu, F. COVID-19: Potential effects on Chinese citizens’ lifestyle and travel. Tour. Rev. 2021, 76, 74–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rittichainuwat, B.N.; Chakraborty, G. Perceived travel risks regarding terrorism and disease: The case of Thailand. Tour. Manag. 2009, 30, 410–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, M.; Lewis, P.; Thornhill, A. Research Methods for Business Students; Pearson Education: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Brochado, A.; Rodrigues, P.; Sousa, A.; Borges, A.P.; Veloso, M.; Gómez-Suárez, M. Resilience and Sustainable Urban Tourism: Understanding Local Communities’ Perceptions after a Crisis. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13298. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151813298

Brochado A, Rodrigues P, Sousa A, Borges AP, Veloso M, Gómez-Suárez M. Resilience and Sustainable Urban Tourism: Understanding Local Communities’ Perceptions after a Crisis. Sustainability. 2023; 15(18):13298. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151813298

Chicago/Turabian StyleBrochado, Ana, Paula Rodrigues, Ana Sousa, Ana Pinto Borges, Mónica Veloso, and Mónica Gómez-Suárez. 2023. "Resilience and Sustainable Urban Tourism: Understanding Local Communities’ Perceptions after a Crisis" Sustainability 15, no. 18: 13298. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151813298

APA StyleBrochado, A., Rodrigues, P., Sousa, A., Borges, A. P., Veloso, M., & Gómez-Suárez, M. (2023). Resilience and Sustainable Urban Tourism: Understanding Local Communities’ Perceptions after a Crisis. Sustainability, 15(18), 13298. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151813298