1. Introduction

Sustainability is one of the most commonly used terms in relation to the way organisations operate. It encompasses the environmental consciousness of management, the expected behaviour of managers and staff, values, and mindset. Depending on the economic sector, industry or organisational activity, the term of sustainability has been defined by many [

1,

2]. In the 1987 UN report Our Common Future, the UN stated that ‘Sustainability is the meeting of the present needs of humankind while preserving the environment and natural resources for future generations’ [

3]. This definition outlines the characteristics of sustainability in general terms, thinking at the societal level. The most serious problems identified are poverty, hunger, climate change, social and economic inequalities, water depletion, the burgeoning energy demand, and environmental pollution. For these, 17 so-called Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) have been identified, along with 169 additional sub-goals. This means that the countries of the world want to act on global problems on the basis of a common set of principles. In the set of objectives to be achieved by 2030, points 8 and 9 summarise the expectations of economic operators. Within this, the key actions that will trigger reflection and action are presented in a non-exhaustive manner:

Economic activities that favour human well-being while respecting general ethical principles.

New models and indicators to support economic growth (alternative economic models).

Rethinking financial systems.

Focus on labour (tackling inequalities (gender, wage, sectoral, etc.), work–life balance, labour law issues).

New technologies and innovative solutions.

Infrastructural solutions (ICT, waste, water, electricity, renewable resources, etc.)

As our study is concerned with research on organisations, the rest of our findings should be interpreted at the organisational level. The most important factors that qualify organisational performance and why it is necessary to address this issue are business efficiency, customer satisfaction, financial stability, reputation, legal obligations, etc. [

4].

The characteristics of organisational functioning that follow sustainability principles have become increasingly clear in recent years, both in theoretical and practical research [

5,

6]. Research shows that sustainable organisations often perform better than their peers, e.g., in terms of social responsibility, employee satisfaction, and financial performance. They often rank among the best employers and succeed in recruiting the most talented employees by often being among the best employers [

7]. A prerequisite for sustainable organisational functioning is the implementation of the characteristics of management according to the principles of sustainability. This condition has a fundamental impact on the performance of the organisation. The expectation is that more and more businesses and economic actors will operate according to the principles of sustainability. To do this, however, they need to understand the following interlinkages.

The survival of the Earth is threatened by the irresponsible use of natural resources and the pollution of the planet. A rethink of organisational functioning and governance is needed to address the resulting environmental problems [

8]. Sustainable business management, or sustainable management, is a new field of research. The main functions of managers in this approach are sustainable planning, sustainable organisation, sustainable leadership, and sustainable control. An eternal debate in management science is the relationship between the terms management and leadership. In their study, Pabian and Pabian [

9] provide evidence that the functions of sustainable management cover a broader range of activities than just sustainable leadership. Business and society have a role to play in this process. If business organisations do not operate in a sustainable way, their impact on local communities can be a problem. The question is: what can leaders of organisations do to create and manage businesses that are more sustainable, both in terms of their internal operations and their external impacts and relationships? Possible solutions have been formulated in different approaches in the literature [

4,

5,

6]. These include Avery and Bergstein’s [

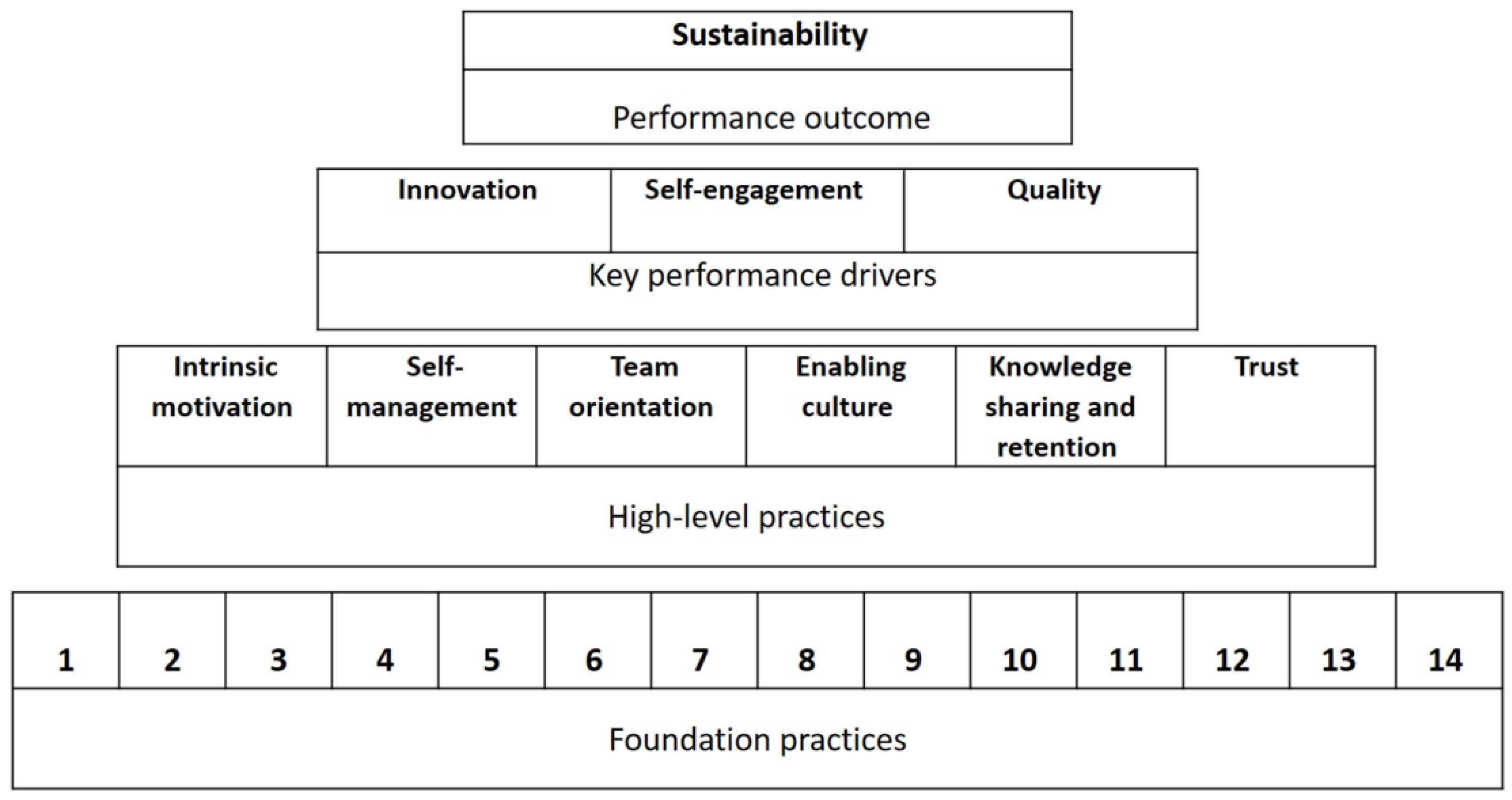

10] Honeybee Pyramid, which contrasts the traditional exploitative (locust) style of management thinking and decision making in the Rhine area with a management style based on the principles of sustainability. Sustainable leadership is about helping organisations to stay at the forefront of their industry, regardless of what is happening in their environment, by focusing on the requirements of sustainability [

11,

12].

We need organisations that create value for themselves, their environment, and society. The aim of this research study is to explore the extent to which managers of Hungarian and Polish SMEs are prepared to manage sustainable organisational operations and meet the criteria for sustainable management.

SMEs are of particular economic importance in Hungary. They also play a key role in employment, and their contribution to GDP is also key. Provisions to support them are laid down by law [

13]. The aim of the law is to support SMEs at national and EU level, thereby promoting the balanced development of the economy and society. The Act takes a multi-pronged approach to the range of support possibilities, but does not set out specific expectations or rules on sustainability. In many cases, professional studies in the domestic context report a lack of preparedness and strategic thinking on the part of SME managers.

The Ministry of Innovation and Technology has developed a strategy for strengthening SMEs for 2019–2030 [

14]. The seven pillars of the SME Strategy aim to increase the added value, productivity, and export capacity of domestic SMEs. The measures cover areas such as cutting red tape and creating a business-friendly tax and regulatory environment, promoting technological change, digitalisation and innovation, access to adequate finance, helping SMEs to enter foreign markets, supporting knowledge transfer, and promoting generational change, taking into account the different needs of enterprises. However, this proposal does not include sustainability requirements for the operation or management of SMEs.

Poland is one of the largest consumer markets and one of the largest economies in the EU. Around 7 million workers are employed in small- and medium-sized enterprises, which form the backbone of the Polish economy. Their top managers believe they can compete with foreign firms. Around two thirds of them say that their products are more competitively priced than those of other EU firms and that the quality and innovation of their products are on a par with other products in EU markets. The question is: is this enough to ensure a sustainable future? According to research funded by Bank Zachodni WBK S.A. [

15], the biggest problem is that they focus mainly on local markets, are risk-averse, and lack management preparedness.

Cooperation between the two countries has historical roots, and one of the pillars of economic relations is based on SMEs. A joint agreement reached in 2017 was based on the recognition that, for Eastern European economies to be competitive and sustainable, they need to work together at regional level on innovative joint projects that can ensure sustainable economic growth in the region [

16]. This cooperation is primarily aimed at supporting and strengthening the SME sector, startups, and family businesses, enabling SMEs to catch up with requirements such as Industry 4.0, smart energy, energy security, ICT, aerospace, smart health, electromobility, and digital education. The requirement for sustainability is not directly expressed here either, but there is an underlying expression of this need.

As SMEs play a significant role in the economies of both countries, they are crucial in causing or eliminating global environmental problems. The preparedness, thinking, and decisions of SME managers have a major impact on whether national economies either cause or reduce damage. Thus, the implementation of sustainable management requirements should be a particular focus for both countries. The shortcomings are almost identical in both countries; therefore, a comparison of their sustainable management practices is justified.

The research questions that the present study aims to explore are as follows:

Q1. Are the expectations of the sustainable management pyramid fulfilled in Hungarian and Polish organisational practice?

Q2. Is there a difference in the management practices of the two countries under study based on the logic of the pyramid?

Q3. Is there a difference between the characteristics of Hungarian and Polish management thinking and behaviour based on the key factors of the pyramid?

In the following sections, the concept of sustainable leadership, its foundations, the characteristics of the nations under study and the research model are presented with a view to answering the research questions. The methodology is then presented, followed by a discussion and presentation of the results. Finally, a short conclusion concludes the paper.

3. Results

The interview question sets were based on the elements of the Honeybee pyramid. The codes, assumptions, and research questions used for the analyses were consistent. To test the first hypothesis, we looked at the practical application of the basic elements of the sustainable leadership pyramid. To validate the second hypothesis, we looked for traits of a trust-based culture. To verify the third hypothesis, we sought to identify the links between innovation and attention to human resources. To prove the fourth hypothesis, it was necessary to examine the basic elements of the pyramid and compare opinions on sustainability. All of our hypotheses were based on a comparison of the two nations. The relationship between the codes, the questions, and our hypotheses is shown in

Table 5.

To confirm our first hypothesis, we analysed the answers to the questions included in the core elements. For each basic element, the five most frequently mentioned concepts are listed (see

Table 6).

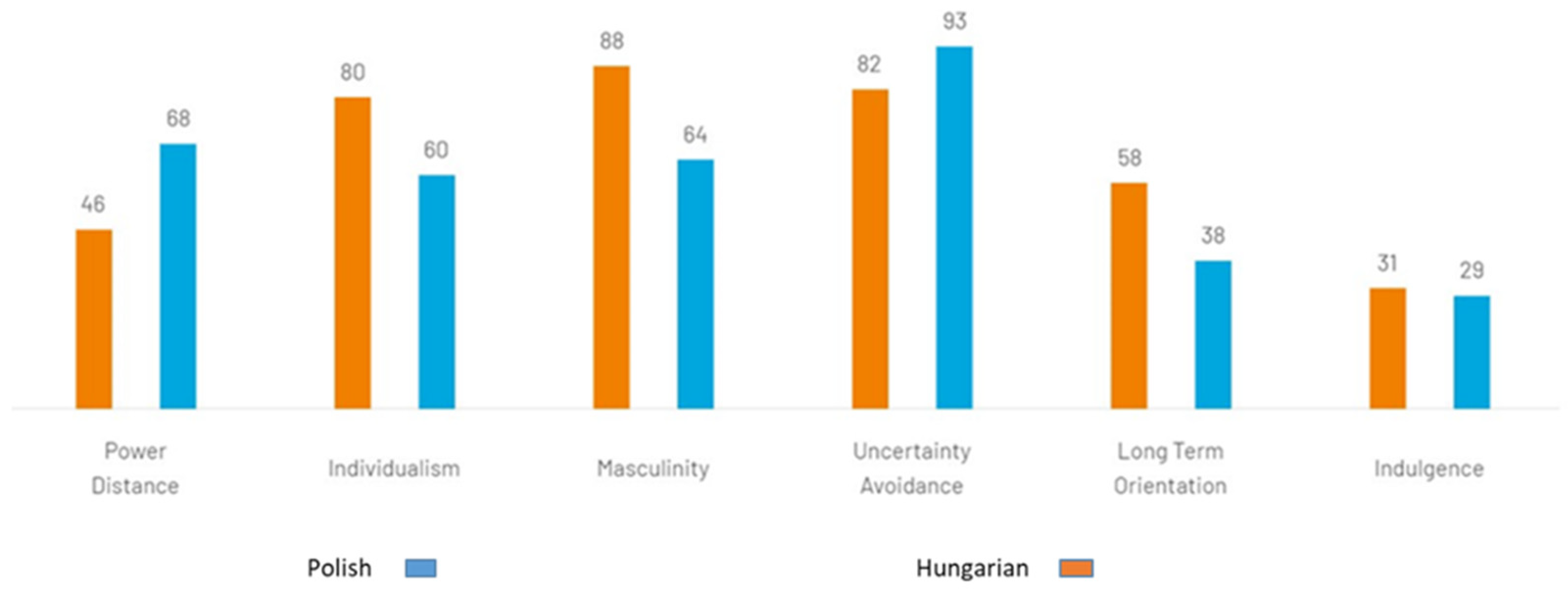

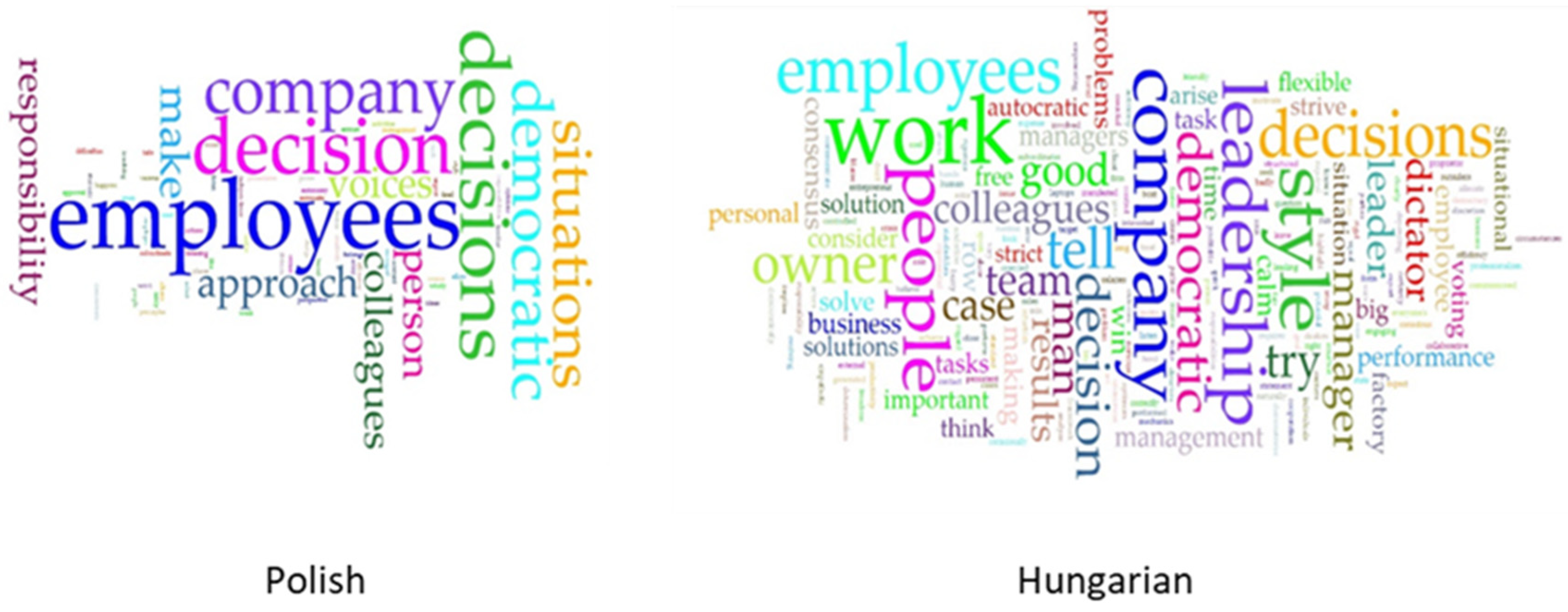

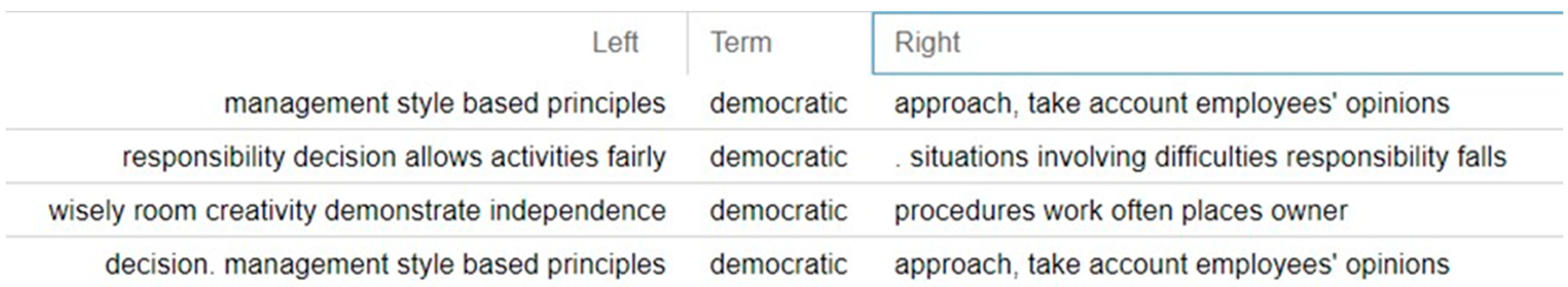

Except for a few elements, most of the expectations are not at the same level. For illustrative purposes, some diagrams have been created to show the similarities and differences. The right leadership style is one of the most important factors. In this case, respondents from both nations consider it important that expectations are met. The word clouds illustrate the most commonly used terms, with the elements being decision, democracy, people, employees, responsibility, team, etc. The words used may not be the same, but there is a similarity in content and meaning (

Figure 3).

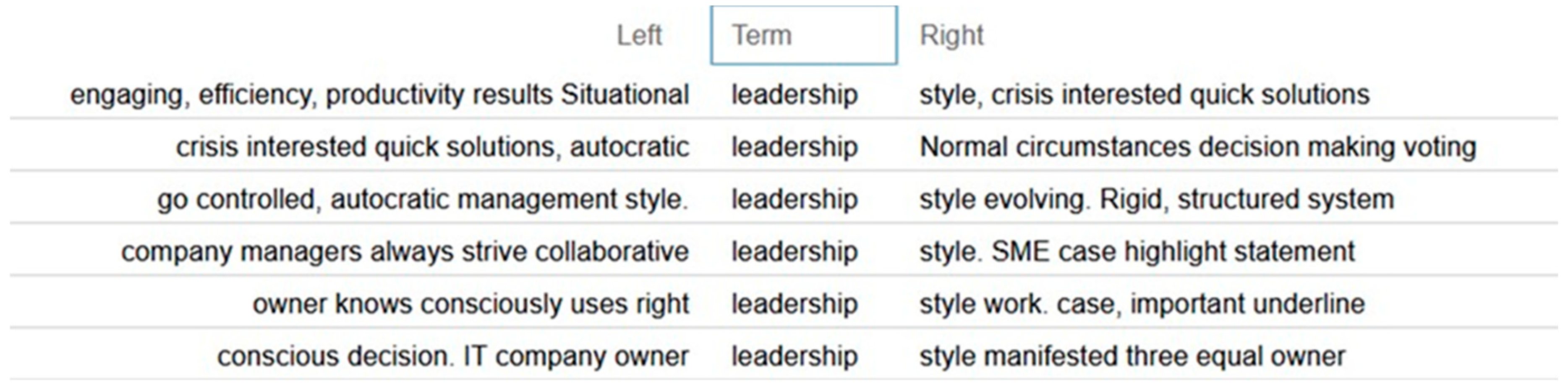

Due to text cleaning, not all of the sentences in the corpus analysed are meaningful, coherent sets of phrases, but for Hungarian respondents, the environmental embeddedness of the leadership phrase illustrates the logic of their thinking. Autocratic styles and decision making only arise in crisis situations; otherwise, they tend to cooperate and agree (

Figure 4).

The environmental embeddedness of the word ‘decision’ in Polish responses also confirms a democratic style (

Figure 5).

When examining the correlation with decision making, both autocratic and consensus indicators show the same significant relationship for Hungarian leaders (see

Table 7). This supports the findings described above that leaders apply democratic or, when necessary, autocratic decision making according to the situation (

p < 0.05).

For Polish respondents, no significant relationship was found with the term decision. The terms decision and democratic show an opposite correlation, but the relationship is not significant. Among the most frequently mentioned terms, the following two significant relationships were found (see

Table 8).

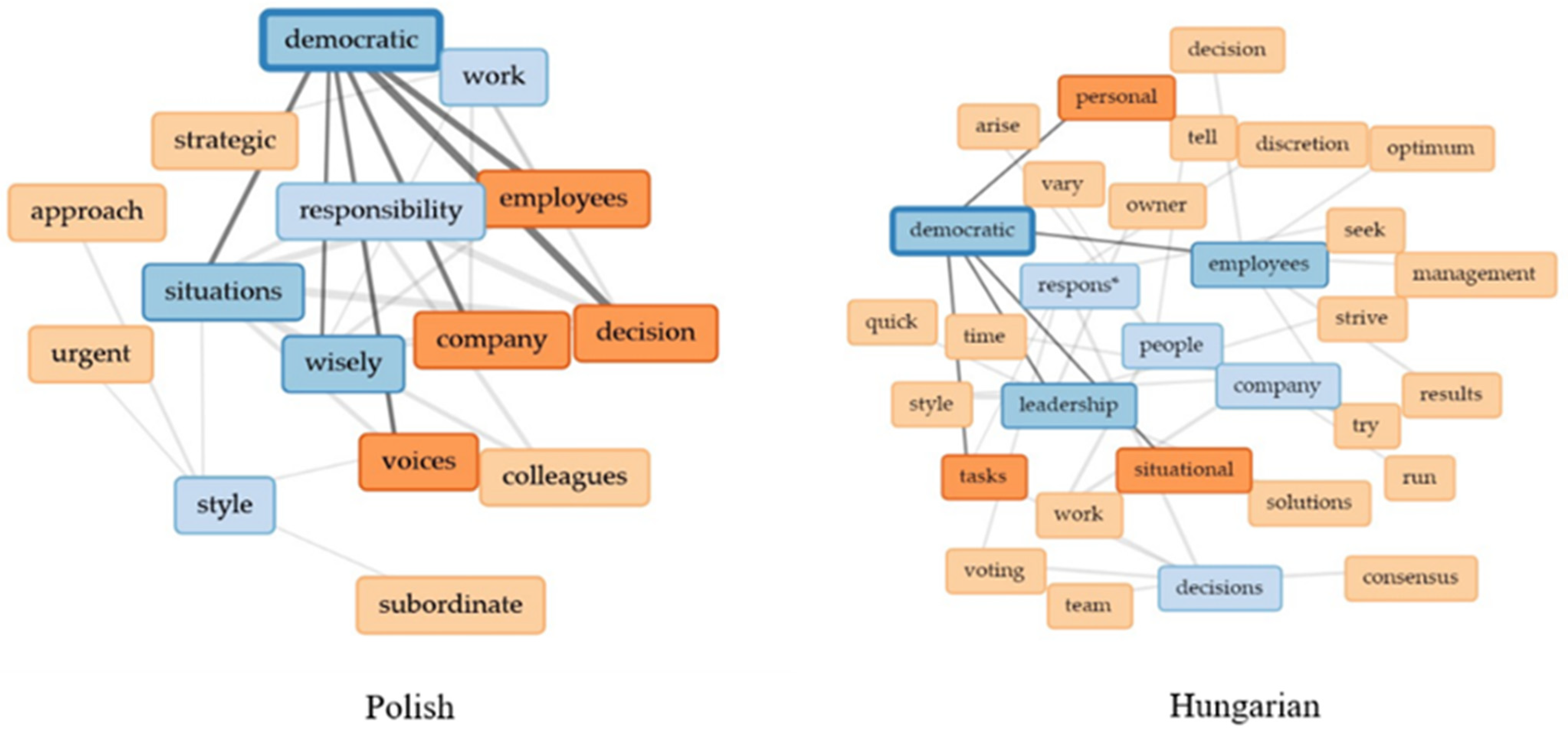

The characteristics of the democratic style are illustrated by the network of the relationships between the terms (

Figure 6).

To prove the hypothesis, we looked at additional elements of the pyramid through correlation relationship analysis. The tables below (

Table 9 and

Table 10) show the significant relationships and the number of basic elements analysed (

p < 0.05).

The results show that there are significant differences between the two nations in all basic elements. These significant relationships are associated with different terms. This shows that managers from the two nations think differently, attaching importance to different characteristics with respect to the requirements of the same coded core element. They have a different set of skills and competencies. Based on these results, we consider the first hypothesis to be confirmed.

The second hypothesis states that ‘The expectations of the sustainable leadership pyramid are not fully met in any nation, but the emphasis is different’.

To verify this hypothesis, the ‘topic’ unit of analysis of the programme was used. The responses to our questions that pertained to all of the elements of the pyramid were analysed first, followed by the responses to our questions that specifically related to sustainability.

During the analysis, the corpus text is segmented by the program. It forms text groups based on the content of the sentences that contain coherent opinions. In this way, it provides a clear overview of what the text is saying, i.e., the text’s substance, and compares the thinking of respondents in the two nations.

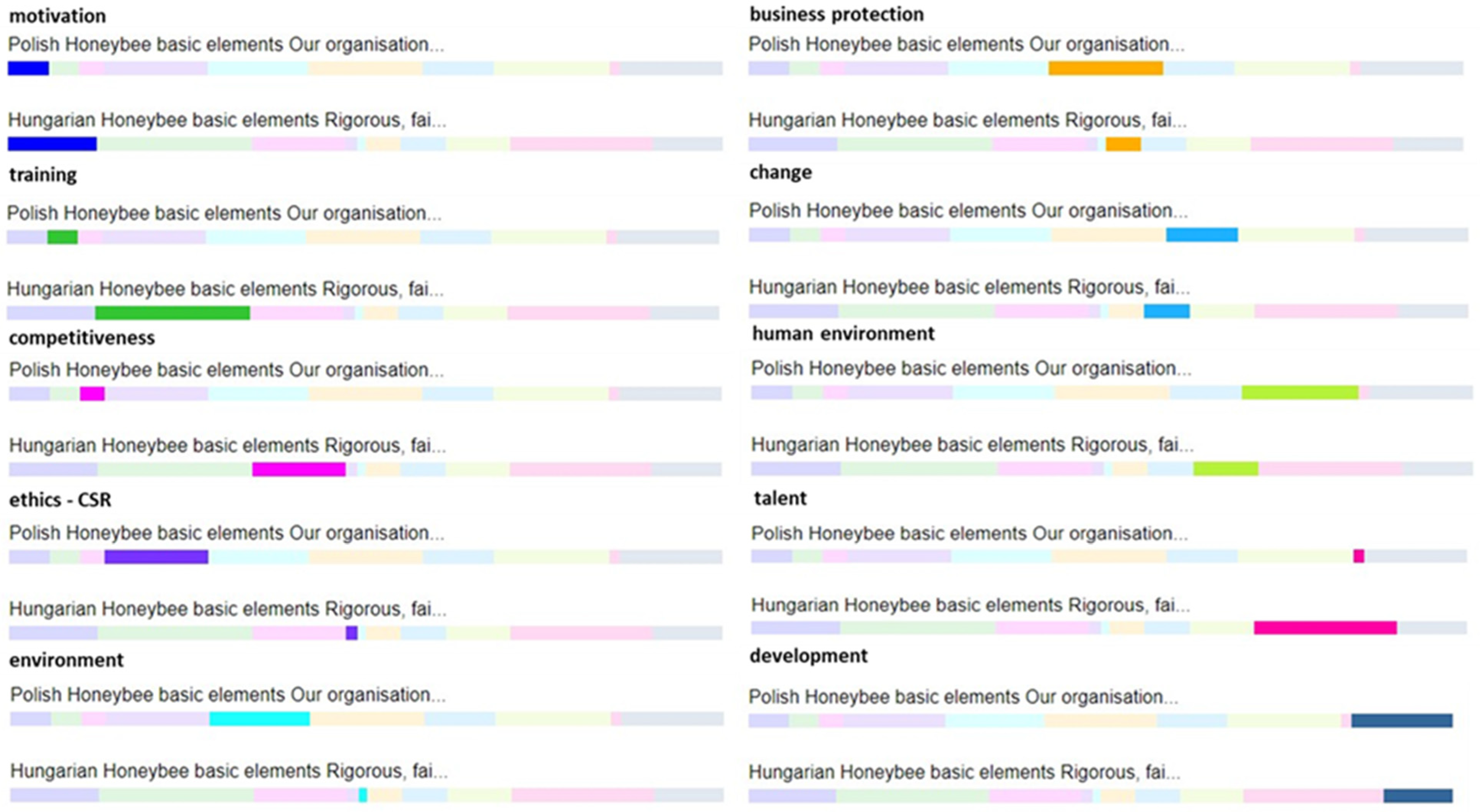

Figure 7 and

Figure 8 below show the results of the analysis of the full corpus, followed by the results of the responses to the sustainability questions. In both cases, the Hungarian and Polish responses are shown below each other on the basis of 10 characteristics, where the different colours represent the weight of the responses in relation to each other. The key terms have been named based on what the segments generated by the program say, which allows for a comparison of the responses from the managers representing the two nations under study.

Although the key terms used in the two analyses are different (generated from the content of the responses), in some cases, identical terms have been assigned to content that bears similarities. These include development, motivation, and human environment.

In both cases, the Polish respondents’ opinion on ‘development’ is dominant. It was mentioned more often not only in relation to sustainability, but was also an important term for them in summarising all questions.

Polish leaders also considered the environment, especially the ‘human environment’, to be more important. This difference is reflected in both comparisons. This difference becomes even more pronounced when comparing the core elements of the Honeybee pyramid, because not only the human environment but also other issues related to the environment are brought to the fore. When comparing the issue of sustainability, the Poles highlighted the importance of communication and growth significantly more frequently in their responses. This is reflected in the comparison of the whole corpus, as business protection is also a priority for them. This thinking is also confirmed by their emphasis on ethics–CSR and their openness to change.

Regarding the Hungarian respondents, the articulation of one’s vision and value judgements focusing on human resources were found to be more important in relation to sustainability. This is evidenced by terms such as satisfaction, health, motivation, and training for development. The last two are also dominant in the comparison of the whole corpus. Overall, Hungarian managers mentioned sustainability more frequently in their responses. Regarding the corpus comparing the core elements of Honeybee, in addition to motivation and training, competitiveness and talent management are also more important for Hungarian managers. Looking at all of the differences, it appears that Hungarian managers’ preference for sustainability is associated with competitiveness and the emphasis on human resources that foster it. For Polish managers, development is ensured by changes in the context of environmental conditions, protection of the business, ethics, and appropriate communication.

Sustainability is of the utmost importance as the final step in the pyramid. Therefore, in addition to comparing the different elements, it is worth looking at the respondents’ views on the possibility of achieving the final step in the pyramid from several perspectives.

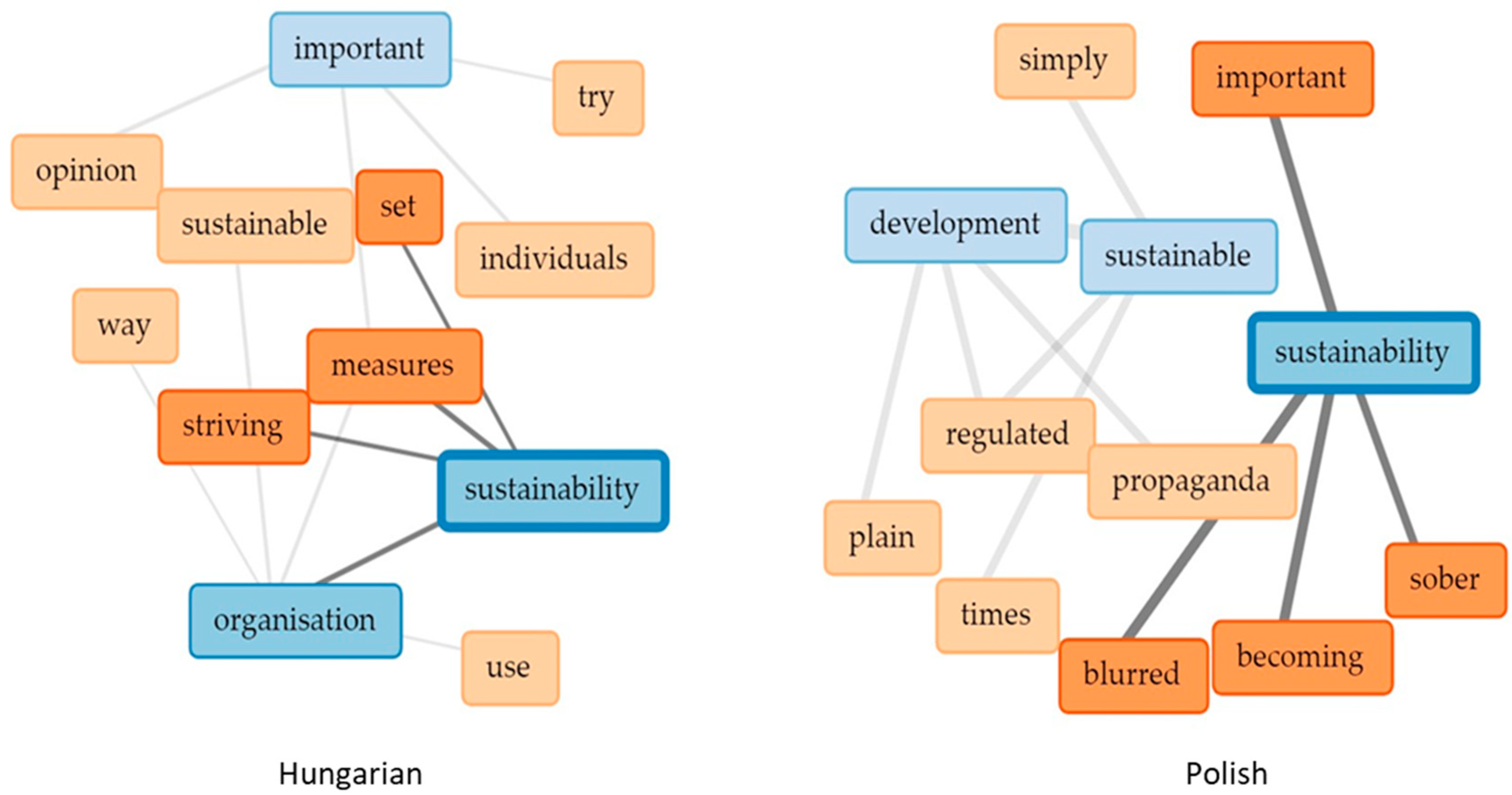

A diagram depicting the most common terms used by respondents and a network of their relationships can be seen in

Figure 9.

Not only is there a difference between the terms used but there is also a difference in the relationships between the same words. The differences in the results are also reflected in the correlation between terms. The term sustainability shows a strong significant relationship with the terms development, company, and concept for Polish respondents (

Table 11).

In the responses of Hungarian managers, the terms environment and activity have a strong significant relationship with the term sustainability (

Table 12).

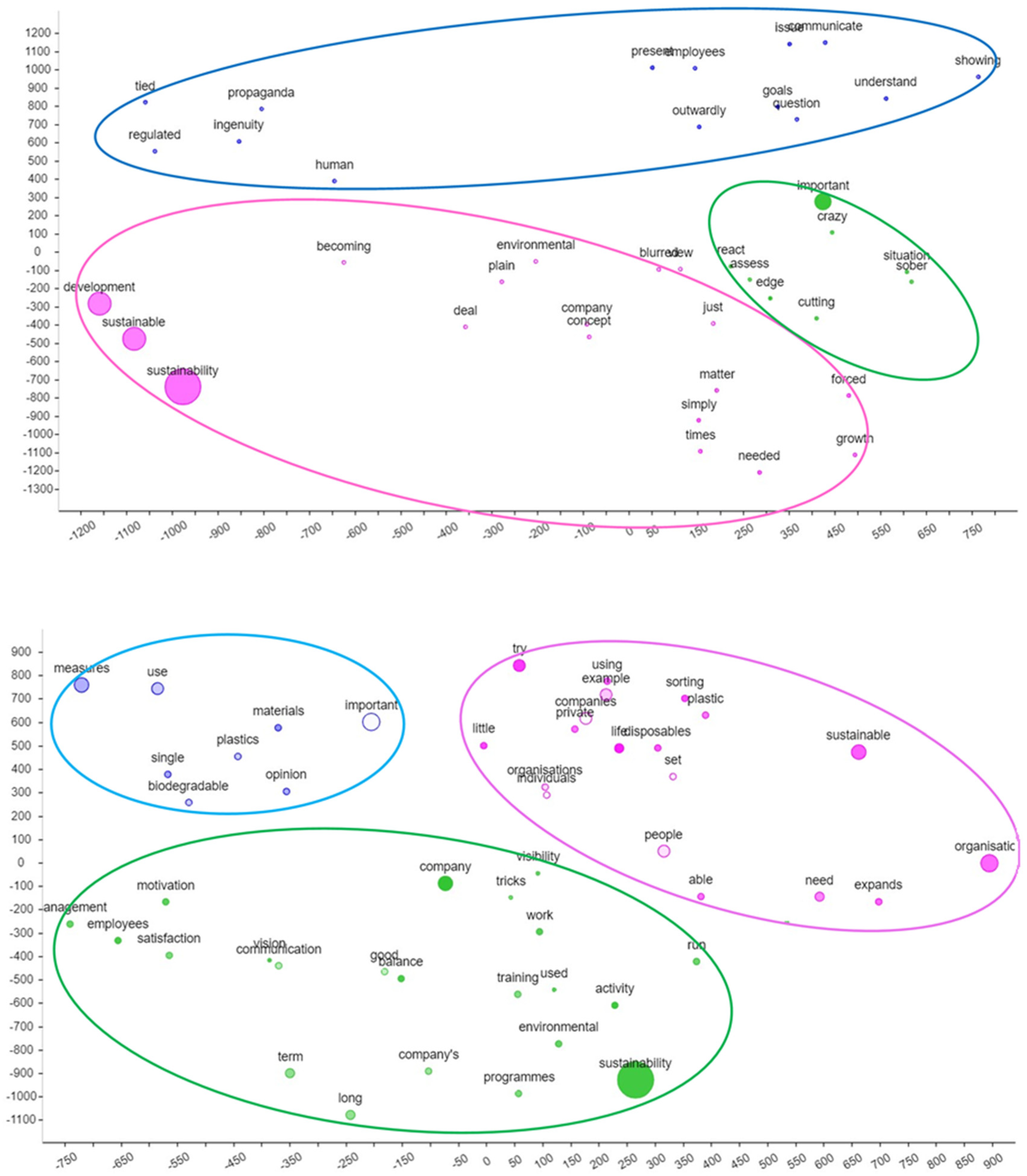

Figure 10 below illustrates the results of our t-SNE analysis; the results are presented based on the most frequently occurring terms for the two nations (the top chart pertains to the Polish sample, while the bottom chart pertains to the Hungarian sample).

In both cases, the t-SNE (t-distributed stochastic neighbour embedding) [

62,

64] statistical method was used to test the relatedness of the terms used in the responses. Several clustering algorithms, such as connectivity-, centroid-, graph-, distributional-, and density-based models, are known. All of them have a common denominator: the goal of clustering data based on the properties of the data. Most clustering techniques are not very successful in representing real, high-dimensional data. Most techniques fail to retain the local and global structure of the data in a single map. The t-SNE method is based on approximating the distribution of the pairwise spacing of words in a multidimensional space by placing them in a two- or three-dimensional space while maintaining the original ratio of the distances between elements. This makes it easy to see how the words are organised and follow and measure differences in meaning. During the visualisation process, the words in the different clusters were displayed in different colours. In the resulting diagram, the distances between the clusters are also clearly visible [

65]. This statistical method is able to capture the nonlinear relationships underlying the structure. It is used when we want to gain an idea of the internal structuring of a set of words, which is important information in this case. The definition of parameters is important for the correct execution of the procedure. For the choice of the parameterization, we followed the recommendations of Wattenberg and colleagues [

63], thus eliminating possible biases. Three ‘clusters’ were obtained. For Polish respondents, the first one includes the terms sustainability, maintenance, development, dominant, which form a close structure; the second one includes adjectives of negligible importance, although the most prominent adjective ‘important’ is also included; and the third includes terms reflecting less positive thinking, such as propaganda, understanding, regulation.

For Hungarian respondents, the first ‘cluster’ includes terms such as sustainable, organisation, people, expand; the second associates sustainability with elements that are necessary for its implementation, namely, programme, communication, motivation, satisfaction, training, balance, staff; and the third links measurement, use, and important terms (see colours).

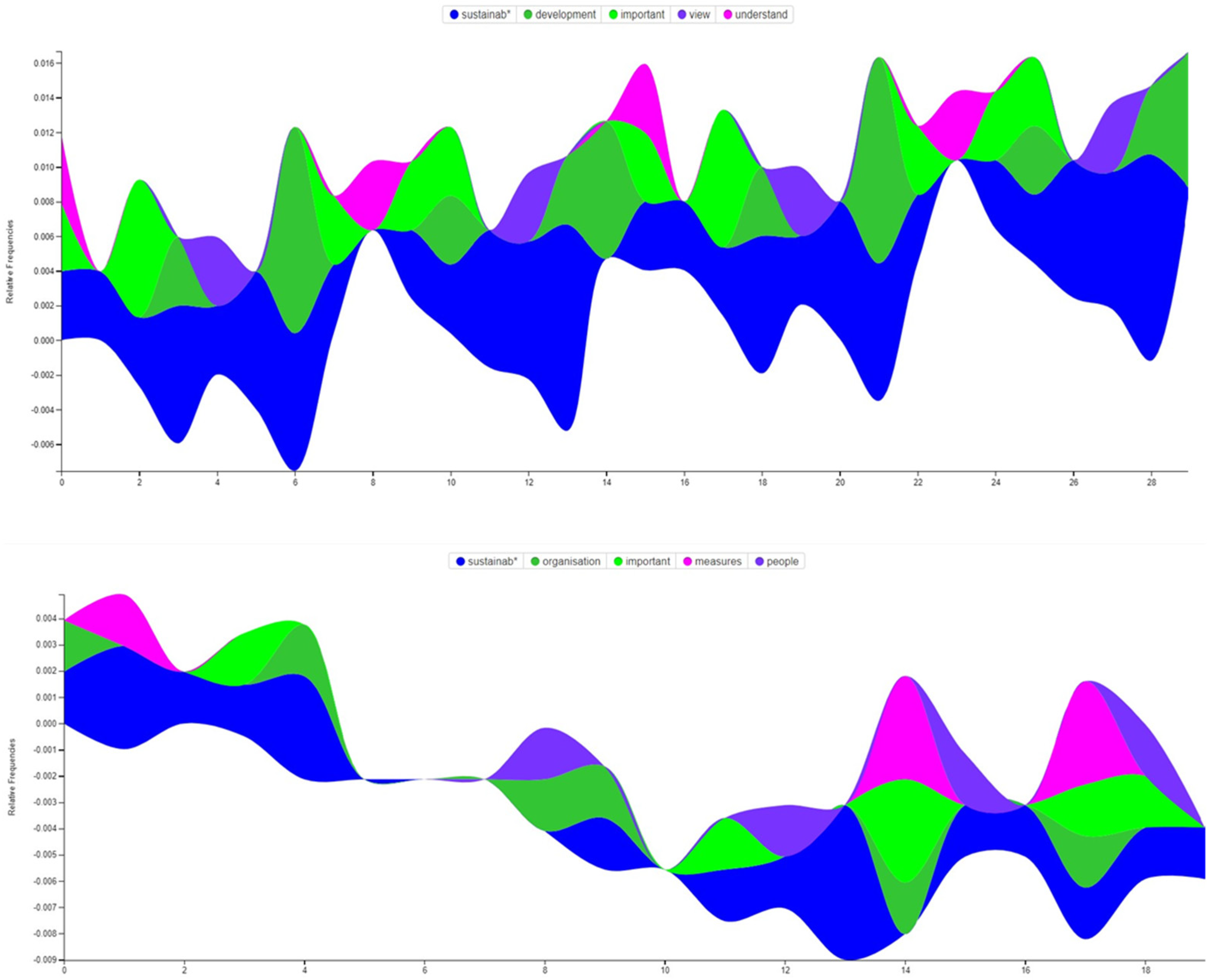

Figure 11 illustrates the frequency of the terms used.

The upper part of

Figure 11 pertain to the Polish sample, and the lower part of the figure pertains to the Hungarian respondents. The difference in thinking can be seen not only in the pattern but also in the terms used. The term sustainability was used much more often by the Poles; for them, the achievement of this expected organisational characteristic is less of a future goal. The term important was used frequently in both cases, but while the Poles emphasised understanding in relation to development, the Hungarians associated it with measuring organisational performance and the use of human resources. From what was said, it seems that the Hungarians are a little further along this path. Polish leaders are still struggling with adoption, while Hungarian leaders are already thinking about the conditions for implementation. This result can be identified by following the basic elements of the Honeybee pyramid. The results summarised in

Table 6 illustrate the level of implementation of each element, indicating the difference between the thinking and styles of the managers belonging to the two nations. The fourth hypothesis is supported by the finding that neither of the two nations fully meets the expectations set out in the elements of the pyramid. Following the results used in the verification of the previous three hypotheses and the diagrams presented here, the fourth hypothesis can also be considered valid.

4. Discussion

The results of this research study could have unique consequences for the literature and practice. In our review of previous research studies, we did not find any studies that have taken a similar approach to our study, i.e., following the logic of the Honeybee pyramid and/or analysing its elements. As mentioned in our literature review, many of the studies that have been carried out pertain to educational institutions and therefore have a different focus [

49,

50]. The analytical logic of the studies on SMEs was based on a different way of thinking and responses from managers of organisations that the researchers assumed were already operating according to sustainability principles regarding their own practices [

54,

59]. Like our results, these studies revealed a number of gaps.

In his comprehensive literature review, Liao [

20] confirms our finding that most research on sustainable leadership is related to the field of education, mainly through qualitative studies. Fewer publications have appeared in the field of business management, which mainly consists of quantitative studies. A questionnaire survey by Suriyankietkaew and Avery [

66] investigated the impact of SL practices on financial performance and other business outcomes in Thai SMEs. Their results showed that 16 out of 23 SL practices were significantly associated with firm financial performance. These results represent a higher level of performance than our results, and their results are markedly better in that social responsibility and a strong shared vision are significant drivers and positive predictors of long-term corporate performance. These elements were not prominent in our study on management practices.

Moursellas and colleagues [

67] interviewed SME managers in four advanced European economies and presented case studies to illustrate the application of sustainability principles. Their study focused more on the sustainable functioning of the organisations. Leadership decisions were strongly driven by support for sustainability and translated into dynamic actions. In a similar vein, much of the previous research on sustainable management has looked at financial performance, efficiency, and performance in the context of sustainable management. Neither of these studies provide outstanding positive or negative results. Kalkavan [

58] and Suriyankietkaew and colleagues [

5] also concluded that the expectations of sustainable leadership were only partially met by the managers in their studies.

Overall, our results are in line with that of Bulmer et al. [

59]. The majority of the managers surveyed show a serious failure to meet the requirements of sustainable leadership.

The present research sought to explore whether and to what extent managers are aware of and use the leadership competences required by the elements of the Honeybee pyramid. It can be seen that the thinking of Avery and Bergsteiner [

10] is significantly ahead of common leadership practice. Neither Asian nor European practice can deliver the requirements to fully meet the expectations. There are elements (mainly requirements that are consistent with traditional management practice) that are naturally identifiable. However, in most cases, the subtleties that make sustainable management thinking different from all of its predecessors are mostly missing. The results of our study are summarised in

Table 13, taking into account the fulfilment of the leadership competences formulated in

Table 3.

Overall, it is a major challenge for managers to move away from the traditional profit-oriented mindset, and in many cases, they would need training to fully understand the essence of this management style.

5. Conclusions

Meeting the requirements of sustainability is not an easy task for the managers of organisations. SMEs are in a particularly difficult situation as, in many cases, they have to make decisions that have an effect on the livelihoods of their own families or immediate environment and, at the same time, on their future survival. It must be accepted that the requirements must be met in both directions if we are to consider the survival of societies in a broader sense. There are many gaps that need to be closed worldwide in order to achieve small but significant changes in cooperation with market economy participants. The present research study offers a small glimpse into the management practices of two Central and Eastern European countries, though they fall far short of the requirements formulated years ago by forward-thinking researchers. In order to facilitate a shift in the right direction, much broader campaigns, more information, and greater education is needed to convey the message that is clearly set out in the logic of sustainable management. Our research is a small step along this path, as we have already, through the interviews, drawn the attention of managers to the need to rethink their management practices. The results of our research could serve as a mirror for all other practitioners to reassess their own beliefs and possible routines.

Our research makes a theoretical contribution to the existing literature regarding SMEs and complements the results of studies on leadership styles. No examples of the application of Honeybee logic were found in the literature in any of the fields. Thus, our research is novel in these areas.

On the practical side, the results are useful for current managers and future managers. They can review the requirements of sustainability leadership and evaluate their own practice. It is constructive for managers to identify their organisation and their own shortcomings and how to remedy them. They can draw conclusions and formulate training plans that can help them to catch up. Our results will hopefully help guide management decisions and support the implementation of the necessary initial or higher-level management initiatives. It is recommended that managers understand the theoretical background of the research in more detail and review the steps and elements of the pyramid and compare them with their own organisation’s practices. This will provide a basis for further decisions.

Limitations of the Research

As with all research, the most critical phase is sampling and access to data. Gathering a sufficient number of responses is always a challenge. This was the case here. In many cases, we received a negative response from the managers we approached, citing either a lack of time or busyness. Another problem is the relevance of the responses. This problem cannot be avoided in interviews. Subjectivity always plays a role. Honesty is risky, especially when it comes to judging one’s own values and behaviour. There may also be a problem of choosing the right methodology and ensuring that it is suitable for both qualitative and quantitative analysis. All evaluation methods, including the ‘Voyant Tools’ application we used, have limitations. For more in-depth studies, it may be necessary to use additional methods of analysis that provide a more accurate picture, both statistically and numerically.

Regarding future research directions, we will seek to recruit more interviewees and expand the current database. We also plan to include more Central and Eastern European countries in our research. Further levels of the Honeybee pyramid are being analysed on the basis of the current database.