Abstract

Background: Problematic smartphone use has increasingly become the focus of attention in recent years. Although it has been noted that parental psychological control is significantly correlated with teenagers’ social anxiety and problematic smartphone use, little is known about how these factors may interact with college students. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to investigate whether social anxiety mediates the association between parental psychological control and problematic smartphone use. Methods: a total of 534 Chinese college students aged 17–25 years (male 59.0%, female 41.0%) participated in the study (M = 20.40, SD = 1.72). The Parental Psychological Control questionnaire, the Social Phobia Inventory, and the Mobile Phone Addiction Tendency Scale were used to evaluate parental psychological control, social anxiety, and problematic smartphone use, respectively. Data were analyzed using the Pearson correlation analysis, regression analysis, and mediation analysis. Results: the results showed that (1) social anxiety was positively correlated with problematic smartphone use among college students, (2) parental psychological control has a significant correlation with college students’ social anxiety, (3) college students’ social anxiety was positively related with problematic smartphone use, and (4) social anxiety plays a mediation role in the association between parental psychological control and problematic smartphone use. Conclusions: in conclusion, social anxiety plays a mediating role in the relationship between parental psychological control and problematic smartphone use, and reducing parental psychological control is an effective intervention means to directly or indirectly reduce college students’ problematic smartphone use. In addition, attention should be paid to parenting styles, and measures should be taken to increase social interaction among college students so as to reduce their problematic smartphone use.

1. Introduction

Mobile phone use brings convenience to people in several ways [1]; however, it is also associated with harmful or potentially disruptive behaviors (e.g., problematic mobile phone use). Problematic mobile phone use is considered to be an individual’s inability to control the use of mobile phones, which consist of several factors (including addiction), and may lead to certain negative effects in daily life [2,3,4]. Billieux et al. [5] proposed a new model and have concluded that problematic mobile phone use does not necessarily fall into the category of behavioral addiction unless it may lead to individual dysfunction. In reality, there is no diagnostic recognition of problematic smartphone use and no consensus on the internet regarding the use of the term ‘addiction’ to talk about problematic smartphone use [6]. Research shows that the rate of problematic smartphone use among college students in some provinces and regions in China is about 25% [7,8]. In recent years, the incidence of problematic smartphone use has been increasing among college students in China. For example, a survey by Shi et al. [9] found that about 41.2% of college students were considered mobile phone addicts. Research has suggested that young people are more at risk of developing addictive disorders because they prefer to explore and seek out new experiences through unhealthy behaviors [10]. Considering that students are more susceptible to the adverse effects of problematic smartphone use, it is of great importance to study the influencing factors and mechanism of problematic smartphone use among college students so as to improve their understanding of problematic smartphone use among them and promote the development of effective intervention means. In the face of the severe COVID-19 disease situation in early 2020, China adopted strict control measures [11], requiring people to stay at home, limiting going out, and delaying students’ return to school. The long-term stay-at-home living and breaking away from the collective environment may be accompanied by changes in various living behaviors of college students, including the frequency of mobile phone use. Although the current outbreak in China is largely over, many college students are infected with COVID-19, which has a large negative psychological impact on them. Research has shown that people’s mobile phone habits may change during the COVID-19 pandemic [12,13]. The COVID-19 pandemic poses a certain threat to the life and safety of every individual [14]. Therefore, college students may pay more attention to negative information such as death cases, internet rumors, and shortage of epidemic prevention materials, resulting in a certain degree of information anxiety. In addition, the academic pressure, employment pressure, interpersonal pressure, and emotional relationship pressure brought by the failure to return to school will aggravate the anxiety state of college students, and college students will choose to relieve anxiety through mobile games or social software [15,16]. College students use smartphones more frequently to meet social, study, and life needs, increasing the risk of problematic mobile phone use. Given the negative impact of the pandemic, smartphone use might have become even more problematic during or after the COVID-19 pandemic.

1.1. Risk Factors for Problematic Smartphone Use

Yang et al. [17] found that problematic smartphone use is associated with a range of negative outcomes, such as poor physical and mental health, academic failure, and relationship problems, and suggested that characteristic procrastination may be a risk factor for problematic smartphone use in college students. In view of the harmfulness of problematic smartphone use to college students’ physical and mental health and social adaptation, the influencing factors of mobile phone use/addiction have attracted the increasing attention of researchers [18,19]. Problematic smartphone use is the result of multiple factors. The bioecological model of human development [20] provides a useful reference for multilevel systematic interventions to examine individual development. According to this model, various factors (including proximal processes, environmental and individual) can influence mobile phone use and addiction among adolescents. For example, Musetti et al. [21] found that childhood trauma and reflective function were significantly correlated with self-problematic mobile phone use through a questionnaire survey. Long et al. [8] found that severe emotional symptoms, high perceived stress, and high parents’ expectations are risk factors for self-problematic use/addiction of college students. In addition, personality traits have been shown to be important predictors of phone addiction [11]. Xing et al. [22] suggested that both parents, especially mothers, reduce their controlling parenting styles and adopt a more adaptive approach to promote the child’s social-emotional development. Another study pointed to an early start of interventions aimed at mitigating individual problematic smartphone use and reducing negative parenting behaviors such as parental psychological controls that have lasting adverse effects [23]. In order to further clarify the formation and development mechanism of problematic smartphone use, it is necessary to consider the perspective of multifactor integration. In view of the lack of current research on the influence of parental psychological control and social anxiety on problematic smartphone use, this study intends to explore the possible mediating role of social anxiety between parental psychological control and problematic smartphone use by building a theoretical model.

1.2. The Role of Parental Psychological Control on Problematic Smartphone Use

Parental control includes behavioral control and psychological control [24]. Parental psychological control is one of the invasive parenting methods, which is often manifested in the use of intrusive psychological control strategies (such as belittling, causing guilt, stopping expressing love to children, etc.) to manage and control children [25]. Previous studies have found that parental control diminishes as adolescents move into adulthood [26], but we suspect that the COVID-19 pandemic may change this relationship. It is revealed that parental psychological control can predict internalized problems, while behavioral control has a stronger ability to predict external problems [27]. According to self-determination theory (SDT) [28], basic psychological needs (including autonomy need, competence need, and relatedness need) are social nutrients for the development of individual autonomous motivation, which may explain the developmental association between parental psychological control and problematic smartphone use. Previous research found that moderate parental psychological control is conducive to children’s development and physical and mental health, but excessive psychological control may lead to a series of internalized problems in children [29]. This kind of negative parenting will limit children’s emotional experience and expression and destroy children’s autonomous development [25]. Studies have shown that individuals who experience high levels of parental psychological control show more anxiety and depression [30]. College students will have more contact with their friends and become increasingly connected with other microsystems such as school or community. Excessive parental control will hinder their personal development and the development of social ability. Empirical studies have found that adolescents’ perceived parental psychological control can significantly predict their problem behaviors [31], such as problematic internet use. Research has further provided support for the theory that controlling and punitive parenting styles are significantly positively correlated with problematic smartphone use among adolescents [32]. In addition, Przybylski et al. [33] demonstrated that adolescents can satisfy their autonomy needs on the internet. However, few previous studies have sought to explore the relationship between parental psychological control and problematic smartphone use in depth.

1.3. The Mediating Role of Social Anxiety

One of the most prevalent anxiety disorders is social anxiety disorder [34], which is characterized by distancing from others in social situations and an intense fear of evaluation. Children’s social maladjustment and social anxiety are directly related to parental psychological control, according to a survey [35]. The family environment is the first environment for individual growth and development [36]; therefore, parental education directly affects the occurrence and development of individual emotions. A previous study has shown that Chinese parents tend to adopt psychological control in the process of educating their children, which has a profound impact on the interpersonal adaptation of college students [37]. College students are in the process of breaking away from family and integrating into collective and social life, and the parent–child relationship begins to change [38]. Parents’ appropriate authoritative education model can make children feel encouraged and supported, thus establishing a sense of security for children, and they can cope with changes in the social environment with low levels of social anxiety [39]. However, Musetti et al. [40] found that problematic social networking site use was positively correlated with indicators of attachment anxiety, and the relationship was influenced by individual, interpersonal, and other related variables. The high level of psychological control and anxious attachment patterns of parents may make college students suffer from psychological problems such as excessive sensitivity. Therefore, they may be reluctant to participate in social activities and feel anxious in interpersonal communication [35]. Individuals with high attachment anxiety tend to have a greater need for social belonging and comfort, which can be achieved through internet use [41].

The college stage is an important period of personality and psychological development, which requires the recognition of a new environment and the new role and reconstruction of self-identity and interpersonal relationships [42]. However, the fear of social avoidance and negative evaluation of social anxiety makes them troubled in interpersonal relationships, and they always hold a negative and evasive attitude to uncertain future situations [43]. This is also consistent with the negative reinforcement emotional processing model; that is, individuals choose addictive behaviors to avoid negative emotions [44]. As an alternative to social interaction, mobile phones can relieve anxiety in the real world [45] and separate the virtual personality from the real one. According to a recent study, people may use their mobile phones as a social technique to avoid dealing with difficult life circumstances or social anxiety [46]. Mobile phones can make those who are unable to establish or maintain social relationships in real life get more opportunities to interact with others and become addicted to them, leading to problematic smartphone use. In addition, it was found that family functioning was a significant negative predictor of cell phone addiction among college students, and loneliness mediated the relationship between family functioning and cell phone addiction [47]. Since the correlation between loneliness and social anxiety has been confirmed in a previous study [48], we hypothesize that social anxiety may be a mediating variable between family functioning and cell phone addiction. To sum up, parental psychological control may increase their social anxiety, thus increasing the problematic use of individual smartphones, leading to problematic smartphone use.

1.4. The Present Study

Chao found that Chinese parents, who have a strong Confucian cultural impact, may have a propensity to embrace controlling parenting practices including psychological control [49]. According to Zha et al., social anxiety disorder is becoming more and more prevalent among Chinese college students, and their average degree of social anxiety is noticeably greater than average [50]. A prior survey found that 21.3 percent of Chinese college students used smartphones in inappropriate ways, and problematic smartphone use has become a public health problem in China [7]. Therefore, it is important to investigate the connection between social anxiety, parental psychological control, and problematic mobile phone use among Chinese college students. The majority of recent research projects have concentrated on the impact of parental psychological control on children’s or adolescents’ mental health prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. However, prior research (particularly in the Chinese setting) has largely ignored the psychological factors behind the link between parental psychological control and problematic smartphone usage among college students. In order to fill this research gap, this study conducted an in-depth investigation into the relationship between them. The innovation of this study, which partially compensates for the deficiency of other studies, is the inclusion of social anxiety as a mediation variable into the mechanism of parental psychological control’s impact on Chinese college students’ problematic smartphone use.

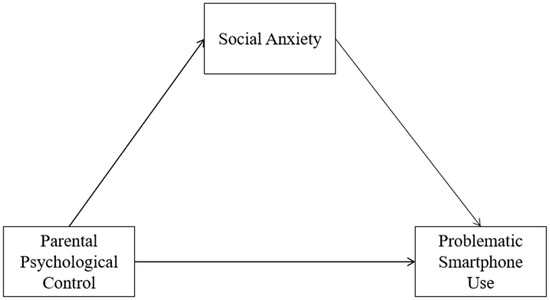

Overall, this study intends to open new perspectives on how parental psychological control and social anxiety could exert a negative effect on problematic smartphone use symptoms among Chinese college students. The findings of this study may also provide this population evidence-based therapies that are useful for lowering problematic smartphone use and enhancing mental health. Based on this, the expected outcome of this study will be the development of clinical and family interventions to reduce problematic smartphone use among college students. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to explain the internal relationships between parental psychological control, social anxiety, and problematic smartphone use, as well as to further examine the link between them among college students. The theoretical model is shown in Figure 1, and the following are the hypotheses of this study:

Figure 1.

Hypothetical model of the association among parental psychological control, social anxiety, and problematic smartphone use.

H1:

Parental psychological control is significantly and positively correlated with problematic smartphone use in college students.

H2:

Parental psychological control is significantly and positively correlated with social anxiety.

H3:

Social anxiety is significantly and positively correlated with problematic smartphone use.

H4:

The relationship between parental psychological control and problematic smartphone use is mediated by social anxiety.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedures

This study adopts a quantitative investigation and research method. A cross-sectional design was adopted to recruit full-time college students. Based on Comrey and Lee’s recommendation of 10 participants per observable variable, the sample size was computed [51,52]. Consequently, a sample size of at least 510 valid cases is needed because the scale has 51 items. However, offline surveys were difficult because of the closure of some universities during the COVID-19 pandemic. As a result, we used the snowball sampling method to find college students or their peers to participate in the online survey [53]. Using the nonprobabilistic sampling strategy known as “snowball sampling”, researchers start with a small group of known participants and then ask those original participants to suggest other people who might be interested in taking part in the study. Data collection was conducted by members of the research team who contacted college students they knew. The participants initially contacted provided the study with contact information for college students who might be interested in participating. All participants were given the identity and contact information of the researcher. Before the formal survey, the researchers issued a cover letter with the instructions, the goal, and the requirements of the questionnaire in order to increase the response rate. Researchers also stressed the confidentiality of responses and the voluntary nature of involvement. Participants were sent an online link to a questionnaire containing a QR code that they could access to prepare for the survey if they were interested. Participants were not rewarded or otherwise paid for answering the questionnaires.

There were 600 questionnaires distributed in all, and 534 of them were retrieved, for an 89% recovery rate. The study was conducted in March–April and October–November 2022, and the participants were from several universities in Shandong province and Guangdong province of China. Given the limitations imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic, the use of online surveys to collect data is quite effective. This removed the requirement for any face-to-face interaction by enabling researchers to call the participants to answer any queries about the study. The inclusion sampling criteria were university students willing to participate in the study, and we excluded those who (a) had chronic diseases and have not participated in any form of clinical therapy, (b) had other mental disorders/addictions other than phone addiction or were participating in additional research or activities, and (c) had post-traumatic stress disorder or were ruminating about something painful. Participants in this study were all voluntary, and this study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shandong University (No. 2021-1-114).

2.2. Instruments

A sociodemographic inquiry was carried out utilizing a scale developed by our research team to guarantee sample representativeness. The following items were included in this section: grade, gender, age, urban/rural origin, etc.

The Chinese version of the Parental Psychological Control Questionnaire (PPCQ) was used to measure parental psychological control. The original questionnaire was compiled by Wang et al. [54], which specifically includes the three dimensions of induced guilt, withdrawal of love, and arbitrary rights, with a total of 18 questions, such as “My parents won’t talk to me till I make them happy again if I break their hearts.” Questions 1 to 10 are the dimension of inducing guilt, questions 11 to 15 are the dimension of withdrawing love, and questions 16 to 18 are the dimension of arbitrary power without reverse scoring. Ratings were taken on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 1, “completely inconsistent”, to 5, “completely consistent”. No item was reverse scored, and the score of the scale is the sum of the score of all questions. The total score ranged from 18 to 90 points—the higher the score, the higher the psychological control level of the parents. Additionally, the previous result showed that the scale had good internal reliability among Chinese college students [55]. For example, Yao et al. [56] found that Cronbach’s α of the PPCQ is 0.90. Similarly, Cronbach’s α of this scale in the present study was 0.910.

The Chinese version of the Social Phobia Inventory (SPIN) is a 17-item (for example, items such as “I have trouble blushing in front of other people.”) self-rated scale that was used to measure social anxiety [57]. The original questionnaire was compiled by Connor et al. [58] and is widely used to assess patients’ physiological and psychological responses to fear, avoidance, and anxiety in social and behavioral environments. The scale consists of 17 items and 3 dimensions, and the response option was prepared with 5-point Likert scale format. No item was reverse scored, and the total score ranged from 0 to 68, with a score >20 indicating the existence of social fear symptoms. A higher score indicates greater social anxiety. Hajure and Abdu [59] found that Cronbach’s α of this scale among a sample of undergraduate students was 0.87. Cronbach’s α of this scale in the present study was 0.925.

The Chinese version of the Mobile Phone Addiction Tendency Scale (MPATS) was used to assess problematic smartphone use. The original questionnaire was compiled by Xiong et al. in 2012 [60]. Yang et al. [61] found that Cronbach’s α of the Chinese scale among Chinese college groups was 0.895. This scale examined withdrawal symptoms, salient behavior, social comfort, and mood change for college students. The scale’s items primarily center on the internal thought processes and subjective social communication experiences of mobile phone users, such as “When the phone is not connected to the line or receives no signals, I will become anxious and irate.” On a 5-point Likert scale, from 0 (extremely inconsistent) to 4 (very consistent), each of the 16 items was scored. No item was reverse scored, and the total score ranged from 0 to 64. Each participant received a composite score based on their answers on the scale, with a higher score suggesting a more severe problematic smartphone use. According to the classification criteria reported by Young [62], a total score of 16–31 is “no problematic smartphone use”, a score of 32–56 is classified as “probable problematic smartphone use”, and a score equal to or greater than 57 is classified as “problematic smartphone use”. Cronbach’s α of this scale in the present study was 0.914.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

The Wenjuanxing questionnaire platform (https://www.wjx.cn, accessed on 1 January 2022) is where the original data were exported from. For data analysis, SPSS 22.0 software (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) was utilized. Means, standard deviations (SD), and percentages were used to analyze descriptive characteristics. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted using AMOS 22.0. The structural equation model was utilized in the current study to verify the model. The fitting index was χ²/df = 3.1, CFI = 0.99, TLI = 0.98, SRMR = 0.01, and RMSEA = 0.06, showing that the model has a good fit. Homogeneity was evaluated with item-total correlations. Item-total correlations and average inter-item correlations of 0.4 or higher were deemed indicative of good reliability. In this study, item-total correlations ranged between 0.41 and 0.71. The Pearson correlation analysis was initially performed to examine the relationships between parental psychological control, social anxiety, and problematic smartphone use. The variance inflation factors (VIF) and tolerance were used to perform a multicollinearity test, where variables with VIF values less than 10 indicate the absence of multicollinearity. The results showed that the variance inflation factor (VIF) was found acceptable (less than 2). Furthermore, the indirect impact of parental psychological control on problematic smartphone use through social anxiety was examined using the SPSS macro PROCESS model 4 with a 95% confidence interval based on 5000 bootstrap samples. In particular, the mediation variable for the mediation analysis was social anxiety, while the independent variable was parental psychological control and the dependent variable was problematic smartphone use. The underlying demographic characteristics were employed as control variables in the mediation analysis. The significance level of all indicators was set as alpha = 0.05, and CI was considered significant when excluding the 0.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

General characteristics of participants among Chinese college students (aged 17–25 years old) are shown in Table 1, and the mean (SD) of parental psychological control, social anxiety, and problematic smartphone use was 46.75 (15.98), 25.25 (14.09), and 29.64 (13.19), respectively (Table 2).

Table 1.

General characteristics of participants among Chinese college students (n = 534).

Table 2.

Descriptive data of participants’ parental psychological control, social anxiety, and problematic smartphone use (n = 534).

3.2. Correlation Analysis

The results in Table 2 also present parental psychological control as being significantly positively correlated with college students’ social anxiety (r = 0.579, p < 0.01). Additionally, there was a strong correlation between problematic smartphone use and parental psychological control (r = 0.594, p < 0.01). The link between social anxiety and problematic smartphone use was also shown to be positively significant (r = 0.574, p < 0.01).

3.3. Mediating Model

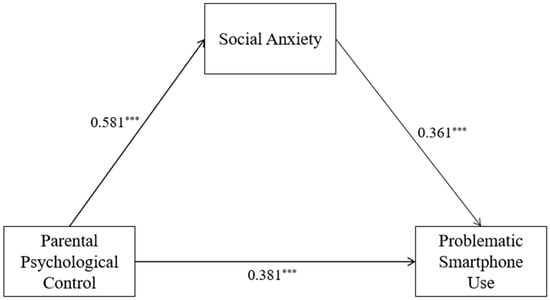

The mediation analysis results in Table 3 present parental psychological control as being significantly associated with problematic smartphone use (95% CI: 0.522–0.661), and the relationship remains significant even when social anxiety was entered (95% CI: 0.302–0.460) (Table 4). The direct effect of parental psychological control on problematic smartphone use is still significant, suggesting a complementary partial mediation. This finding may suggest that not only can parental psychological control be directly related to problematic smartphone use but may also be associated with problematic smartphone use indirectly through social anxiety (Figure 2); 64.4% and 35.6% of the total effect were accounted for by the direct and indirect effects, respectively.

Table 3.

Regression coefficients of the mediating of social anxiety between parental psychological control and problematic smartphone use (n =534).

Table 4.

Mediating effects of social anxiety between parental psychological control and problematic smartphone use by process. Demographic variables as covariates (n =534).

Figure 2.

The mediating effect of parental psychological control on problematic smartphone use through social anxiety. Note: *** p < 0.001.

4. Discussion

The present study investigated the relationships among parental psychological control, social anxiety, and problematic smartphone use in college students. The mediating function of social anxiety in the connection between parental psychological control and problematic smartphone use was investigated using a simple mediation model. Specifically, social anxiety significantly mediates the relationship between parental psychological control and problematic smartphone use. This study offers some recommendations for providing effective clinical therapies for social anxiety and psychological control in parents in order to decrease problematic smartphone use among college students and promote the development of their mental health.

4.1. Effect of Parental Psychological Control and Problematic Smartphone Use

The results of this study reveal the negative impact of parental psychological control on reducing college students’ problematic smartphone use. Our findings agree with those of earlier researchers [63]. Research conducted by Lee et al. found a positive correlation between parental psychological control and problematic smartphone use among adolescents [64]. Social control theory [65], which suggested that young people are more likely to engage in health-risk behaviors when they fail to connect with society, can help to understand this result. Affected by the COVID-19 epidemic, college students mostly stay at home and stay with their parents for a long time; therefore, their psychology and behavior will inevitably be affected by family relationships. Parental psychological control is closely related to low social connection, which can undermine adolescents’ and college students’ needs for autonomy and the development of interpersonal relationships, resulting in some problematic behaviors such as problematic smartphone use [66,67]. In addition, individuals who experienced high levels of parental psychological control showed more anxiety and depression, while individuals with high levels of anxiety and depression had higher levels of mobile phone dependence [68]. The control strategy of criticism and blame in parental psychological control may bring negative emotions of pressure, pain, and loneliness to college students [25]. In order to vent and relieve these negative emotional experiences, college students easily seek comfort from the internet world through smartphones [69]. The research results also support the SDT [28], which holds that self-determined and non-self-determined behaviors may be used to classify people’s actions. The behavior of the individual caused by parental psychological control belongs to the control orientation, which will lead to the individual’s independent needs not being satisfied [70]. Furthermore, it may lead to the reduction in the individual’s internal motivation, which is not conducive to the individual’s cognitive, emotional, and other psychological developments. At the same time, the psychological control of parents will also create obstacles in the interpersonal communications of teenagers and college students and lead to the other two basic needs, relationship needs and competence needs, not being satisfied [30,71], which will make teenagers seek psychological needs from the network. Therefore, the level of parental psychological control has an influence on adolescents’ tendency toward problematic smartphone use.

4.2. The Association between Social Anxiety, Parental Psychological Control, and Problematic Smartphone Use

It is not unexpected that parental psychological control had a negative effect on social anxiety in the study, and the conclusion is consistent with previous studies. Especially, the higher the level of parental psychological control is, the more likely college students will have anxiety on social occasions, affecting interpersonal relationships. The results are consistent with Wang et al.’s research that parental psychological control is the negative side of control and can negatively predict individual psychological development in different cultures [54]. High-level psychological control can lead to internal and external problems such as the anxiety and withdrawal of college students, which proves that the negative parenting mode of parental psychological control is not conducive to the psychological development of children [72]. Self-consciousness develops rapidly in college, but when faced with psychological control from parents, the self-confidence and independence of college students will be frustrated. The higher the level of parental psychological control, the more likely the college students are to feel frustrated and lack judgment. Moreover, parents’ excessive interference in children’s growth space leads to college students’ inability to relax on social occasions, which easily leads to withdrawal and avoidance behaviors [67]. Social control theory can also explain this result. Specifically, parental psychological control of college students tends to lead to low social connection and anxiety in social situations [65]. Moreover, parental psychological control that withdraws love and triggers feelings of guilt may directly cause students’ negative emotions, and long-term negative emotions will lead to the damage to the self-repair function [44]. This kind of internal and external conflict causes teenagers to deny themselves and others, thus showing independence, rejection, and withdrawal behavior in social interaction.

4.3. The Mediating Role of Social Anxiety

This study also discovered that social anxiety mediates the association between parental psychological control and problematic smartphone use. Social anxiety was related to problematic smartphone use, which is consistent with previous research [73]. A significant relationship between social anxiety and problematic phone use was found by Wang et al.’s research [74]. Individuals with social anxiety tend to have negative feelings in social situations in real life, while mobile network social interaction makes individuals feel more comfortable and natural in the virtual communication process [75]. Such negative feelings reinforce their use of mobile phones and are more likely to cause phone addiction. The cognitive–behavioral model of rational internet use also points out that social anxiety, as one of the inappropriate cognitions, is the cause of individual pathological internet use [76]. Individuals with high social anxiety take a negative approach to uncertain events and may avoid real social situations [77]. They are more inclined to seek psychological comfort from virtual social platforms and choose online information exchange instead of traditional face-to-face communication. From the perspective of SDT, parental psychological control during the epidemic may require college students to think and act according to their requirements, which is not conducive to the satisfaction of their autonomous needs at this stage. In addition, excessive parental involvement in the decision-making and emotional processes of children and adolescents may weaken their confidence in socially challenging tasks, and they may fear or even avoid making independent decisions, resulting in social anxiety. The essence of problematic smartphone use is that individuals overuse and rely too much on mobile phones. Previous studies have shown that social anxiety can lead to behavioral problems such as interpersonal relationship loss and problematic smartphone use [78]. According to the cognitive–behavioral model of the causes of social anxiety, social anxiety patients have a certain degree of cognitive dissonance and have a deviation in the processing of external information [79]. The social function of mobile phones can effectively meet the interpersonal communication needs of individuals with social anxiety [80]; therefore, they may spend more time on mobile phones, resulting in problematic smartphone use. In addition, socially anxious individuals also use mobile phones to relieve negative emotions [81], which is another major reason why they are more prone to problematic smartphone use. Based on the research results, we speculate that college students who feel the high intensity of parental psychological control will not show their abilities in all aspects. In this case, individuals may be afraid to communicate with others, resulting in social fear and anxiety, and internal anxiety prevents normal communication with the surrounding environment. Therefore, college students will choose to spend a lot of time in the virtual world to meet their social needs and may depend on some negative information on the network that will harm their physical and mental health, and eventually, the symptoms of problematic smartphone use appear.

4.4. Implications

To the best of our knowledge, this study was the first attempt to examine the relationship between parental psychological control and problematic smartphone use with the mediating effect of social anxiety among college students. Theoretically, the study’s findings offer more in-depth theoretical explanations of how parental psychological control affects college students’ problematic smartphone use. In addition, the SDT and social control theory support our study. Based on our findings, interventional guidance for schools or families can be provided to formulate intervention measures to reduce problematic smartphone use among Chinese college students during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. Considering the Chinese cultural context, professionals working on education or intervention programs may promote children’s socio-emotional development by advising both parents to reduce controlling parenting and adopt more adaptive parenting styles. Moreover, the psychological counseling center set up by the school can provide psychological assistance to college students who have some psychological problems and relieve their psychological discomfort.

Important clinical implications for the management of problematic smartphone use flow from the study’s findings as well. A detailed understanding of the influence mechanism of parental psychological control and social anxiety on problematic smartphone use in college students during and after the COVID-19 pandemic may be the key to clinical prevention and intervention. For example, research by Roos et al. [82] points out that new technologies to provide digital psychological services to families are playing a crucial role, including evidence-based telemedicine services through digital parenting interventions to intervene in parental parenting styles. The results suggest that parents may be more likely to exert psychological control over college students in the special context of the COVID-19 pandemic, which may promote social anxiety among college students, leading them to avoid social activities and devote more personal time to problematic mobile phone use. Therefore, the intervention measures of clinical workers should focus on the psychological control of college student’s parents and take some measures to guide parents to reduce their psychological control over their children, which may reduce the social anxiety of college students and the tendency of problematic smartphone use. For example, the intervention method of family therapy can be used clinically to better directly intervene in parental psychological control by dealing with parent–child interaction patterns, adjusting family rules and boundary reconstruction [83].

4.5. Limitations

However, there are some limitations to this study. First, self-reported scales are solely used in the study to investigate the relationship between variables, which cannot represent the real situation of the subjects to some extent. Scenario experiments can be set up to test their real responses in the experiment in the future. Second, strict experimental results cannot be inferred from the cross-sectional design, and a longitudinal follow-up study can be used to investigate the causal relationship between parental psychological control and problematic smartphone use. Considering the reverse causal view that problematic smartphone use drives social anxiety or parental psychological control has been neglected in current research; therefore, future research needs longitudinal and experimental approaches to ascertain directionality [84]. Third, due to the limitations of the epidemic, the sample size is small. Small sample size, male preponderance, and urban preponderance bound the generalizability of the results and might impact the statistical analyses. Therefore, we can choose a larger sample size and more groups to explore the relationship in the future. Finally, problematic smartphone use is affected by a variety of factors, and other factors may exist (for example, the mediating role of variables such as loneliness and basic psychological needs or the moderating role of social support). Therefore, other factors can be incorporated into the model in the follow-up study to further explore the influence and mechanism of parental psychological control on the problematic smartphone use of college students. Moreover, Lo Cascio et al. [85] found that the development level of individual self-esteem was significantly correlated with parental psychological control, which is a negative parenting style. Individuals with a low level of self-esteem often evaluate themselves in a negative way and tend to think that others evaluate them in the same way. In social interaction, such expected negative evaluation will easily lead to the emergence of social anxiety. Thus, self-esteem may be a potential protective factor related to social anxiety stemming from parental psychological control. Finally, demographic variables will be used to investigate potential differences.

5. Conclusions

The current study is the first to incorporate a psychological mechanism (i.e., social anxiety) into the relationship between parental psychological control and problematic smartphone use in college students, which provides new evidence for the hypothetical model. Our results showed that parental psychological control had a direct significant impact on problematic smartphone use. Additionally, parental psychological control had an indirect significant impact on problematic smartphone use through the mediating role of social anxiety. The current study has limitations with cross-sectional research; future studies could consider longitudinal or experimental studies to further validate our model. It is suggested that families should pay attention to the proper transformation of their education mode to reduce college students’ social anxiety levels and their problematic smartphone use. In addition, helping college students whose parents have high levels of psychological control to reduce their social anxiety will be important in the future clinical treatment of problematic smartphone use. In future studies, intervention programs for parental psychological control and social anxiety can be designed to reduce the prevalence of problematic smartphone use among Chinese college students.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.Z. and Z.L.; methodology, Z.L.; software, S.W.; validation, Z.L. and S.W.; formal analysis, X.Z.; investigation, Z.L.; resources, S.W.; data curation, X.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.L.; writing—review and editing, X.Z.; visualization, X.Z.; supervision, Z.L.; project administration, X.Z.; funding acquisition, X.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Social and Science Planning Project of Shandong province (No. 20DTYJ03).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Shandong University (No. 2021-1-114).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the participants for their efforts in our study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Billieux, J. Problematic use of the mobile phone: A literature review and a pathways model. Curr. Psychiatry Rev. 2012, 8, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Fernandez, O.; Kuss, D.J.; Griffiths, M.D.; Billieux, J. The conceptualization and assessment of problematic mobile phone use. Encycl. Mob. Phone Behav. 2015, 591–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billieux, J.; Philippot, P.; Schmid, C.; Maurage, P.; De Mol, J.; Van der Linden, M. Is dysfunctional use of the mobile phone a behavioural addiction? confronting symptom-based versus process-based approaches. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2015, 22, 460–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choliz, M. Mobile phone addiction: A point of issue. Addiction 2010, 105, 373–374. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Billieux, J.; Maurage, P.; Lopez-Fernandez, O.; Kuss, D.J.; Griffiths, M.D. Can disordered mobile phone use be considered a behavioral addiction? An update on current evidence and a comprehensive model for future research. Curr. Addict. Rep. 2015, 2, 156–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panova, T.; Carbonell, X. Is smartphone addiction really an addiction? J. Behav. Addict. 2018, 7, 252–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Liu, F.; Ding, S.; Ying, X.; Wang, L.; Wen, Y. Gender differences in factors associated with smartphone addiction: A cross-sectional study among medical college students. BMC Psychiatry 2017, 17, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, J.; Liu, T.Q.; Liao, Y.H.; Qi, C.; He, H.Y.; Chen, S.B.; Billieux, J. Prevalence and correlates of problematic smartphone use in a large random sample of Chinese undergraduates. BMC Psychiatry 2016, 16, 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, M.; Zhai, X.; Li, S.; Shi, Y.; Fan, X. The Relationship between Physical Activity, Mobile Phone Addiction, and Irrational Procrastination in Chinese College Students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomei, A.; Petrovic, G.; Simon, O. Offline and Online Gambling in a Swiss Emerging-Adult Male Population. J. Gambl. Stud. 2022, 38, 1215–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, C.; Zhang, R. COVID-19 in China: Responses, challenges and implications for the health system. Healthcare 2021, 9, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S. Coping with COVID-19: The Medical, Mental, and Social Consequences of the Pandemic; Wolters Kluwer Health: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Li, G.; Conti, A.A.; Qiu, C.; Tang, W. Adolescent mobile phone addiction during the COVID-19 pandemic predicts subsequent suicide risk: A two-wave longitudinal study. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, W.X.; Li, B.; Han, S.S.; Han, Y.H.; Meng, S.Q.; Guo, Q.; Ke, Y.Z.; Zhang, J.Y.; Cui, Z.L.; Ye, Y.P.; et al. Current Status and Correlation of Physical Activity and Tendency to Problematic Mobile Phone Use in College Students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Liu, Z.; Zou, Z.; Wang, F.; Zhu, M.; Zhang, W.; Tao, H.; Ross, B.; Long, Y. Changes of psychotic-like experiences and their association with anxiety/depression among young adolescents before COVID-19 and after the lockdown in China. Schizophr. Res. 2021, 237, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muyor-Rodriguez, J.; Caravaca-Sanchez, F.; Fernandez-Prados, J.S. COVID-19 Fear, Resilience, Social Support, Anxiety, and Suicide among College Students in Spain. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Wang, P.; Hu, P. Trait Procrastination and Mobile Phone Addiction Among Chinese College Students: A Moderated Mediation Model of Stress and Gender. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 614660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alavi, S.S.; Ghanizadeh, M.; Mohammadi, M.R.; Mohammadi Kalhory, S.; Jannatifard, F.; Sepahbodi, G. The Survey of Personal and National Identity on Cell Phone Addicts and Non-Addicts. Iran. J. Psychiatry 2018, 13, 15–21. [Google Scholar]

- Park, S.Y.; Yang, S.; Shin, C.S.; Jang, H.; Park, S.Y. Long-Term Symptoms of Mobile Phone Use on Mobile Phone Addiction and Depression Among Korean Adolescents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U.; Morris, P.A. The Bioecological Model of Human Development. In Handbook of Child Psychology: Theoretical Models of Human Development; Lerner, R.M., Damon, W., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006; pp. 793–828. [Google Scholar]

- Musetti, A.; Brazzi, F.; Folli, M.C.; Plazzi, G.; Franceschini, C. Childhood trauma, reflective functioning, and problematic mobile phone use among male and female adolescents. Open Psychol. J. 2020, 13, 242–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, S.; Gao, X.; Song, X.; Archer, M.; Zhao, D.; Zhang, M.; Ding, B.; Liu, X. Chinese Preschool Children’s Socioemotional Development: The Effects of Maternal and Paternal Psychological Control. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, S.; Hu, X. Parenting and mobile phone addiction tendency of Chinese adolescents: The roles of self-control and future time perspective. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 985608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barber, B.K.; Olsen, J.E.; Shagle, S.C. Associations between parental psychological and behavioral control and youth internalized and externalized behaviors. Child Dev. 1994, 65, 1120–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barber, B.K. Parental psychological control: Revisiting a neglected construct. Child Dev. 1996, 67, 3296–3319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shek, D.; Dou, D. Perceived parenting and Parent-Child relational qualities in fathers and mothers: Longitudinal findings based on hong kong adolescents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lam, B.; Raine, A.; Fung, A.; Gao, Y.; Lee, T. Caregivers’ grit moderates the relationship between children’s executive function and aggression. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Yu, C.; Chen, J.; Sheng, J.; Hu, Y.; Zhong, L. The association between parental psychological control, deviant peer affiliation, and internet gaming disorder among chinese adolescents: A Two-Year longitudinal study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soenens, B.; Park, S.Y.; Vansteenkiste, M.; Mouratidis, A. Perceived parental psychological control and adolescent depressive experiences: A cross-cultural study with Belgian and South-Korean adolescents. J. Adolesc. 2012, 35, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunz, J.H.; Grych, J.H. Parental psychological control and autonomy granting: Distinctions and associations with child and family functioning. Parent. Sci. Pract. 2013, 13, 77–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, L.; You, X.; Huang, J.; Yang, R. Who overuses Smartphones? Roles of virtues and parenting style in Smartphone addiction among Chinese college students. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 65, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przybylski, A.K.; Rigby, C.S.; Ryan, R.M. A motivational model of video game engagement. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2010, 14, 154–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, R.C.; Petukhova, M.; Sampson, N.A.; Zaslavsky, A.M.; Wittchen, H.U. Twelve-month and lifetime prevalence and lifetime morbid risk of anxiety and mood disorders in the United States. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 2012, 21, 169–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Creveling-Benefield, C.C.; Varela, R.E. Parental psychological control, maladaptive schemas, and childhood anxiety: Test of a developmental model. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2019, 28, 2159–2171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitzman-Ulrich, H.; Wilson, D.K.; St, G.S.; Lawman, H.; Segal, M.; Fairchild, A. The integration of a family systems approach for understanding youth obesity, physical activity, and dietary programs. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2010, 13, 231–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pomerantz, E.M.; Wang, Q. The role of parental control in children’s development in western and east Asian countries. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2009, 18, 285–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valladares, M.; Ramirez-Tagle, R.; Munoz, M.A.; Obregon, A.M. Individual differences in chronotypes associated with academic performance among Chilean University students. Chronobiol. Int. 2018, 35, 578–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Xiao, R.; Yang, X.; Chen, Y.; Peng, F.; Zhou, S.; Zeng, X.; Zhang, X. Parenting style and emotional distress among Chinese college students: A potential mediating role of the zhongyong thinking style. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musetti, A.; Manari, T.; Billieux, J.; Starcevic, V.; Schimmenti, A. Problematic social networking sites use and attachment: A systematic review. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2022, 131, 107199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Ma, J.L. Adult Attachment Style, Emotion Regulation, and Social Networking Sites Addiction. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lea, S.; Martins, A.; Morgan, S.; Cargill, J.; Taylor, R.M.; Fern, L.A. Online information and support needs of young people with cancer: A participatory action research study. Adolesc. Health Med. Ther. 2018, 9, 121–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, P. Evolution and social anxiety. The role of attraction, social competition, and social hierarchies. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2001, 24, 723–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, T.B.; Piper, M.E.; McCarthy, D.E.; Majeskie, M.R.; Fiore, M.C. Addiction motivation reformulated: An affective processing model of negative reinforcement. Psychol. Rev. 2004, 111, 33–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weidman, A.C.; Levinson, C.A. I’m still socially anxious online: Offline relationship impairment characterizing social anxiety manifests and is accurately perceived in online social networking profiles. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 49, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Xie, J.; An, L.; Hou, G.; Jian, H.; Wang, W. A generalizability analysis of the mobile phone addiction tendency scale for chinese college students. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 10, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.R.; Sun, J.; Ye, J.N.; Hou, X.H.; Xiang, M.Q. Family functioning and mobile phone addiction in university students: Mediating effect of loneliness and moderating effect of capacity to be alone. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1076852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmer, E.M.; van Tilburg, T.; Fokkema, T. Minority Stress and Loneliness in a Global Sample of Sexual Minority Adults: The Roles of Social Anxiety, Social Inhibition, and Community Involvement. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2022, 51, 2269–2298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, R.K. Beyond parental control and authoritarian parenting style: Understanding Chinese parenting through the cultural notion of training. Child Dev. 1994, 65, 1111–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zha, Y.; Tang, Q.; Jin, X.; Cai, X.; Gong, W.; Shao, Y.; Weng, X. Development of social anxiety cognition scale for college students: Basing on Hofmann’s model of social anxiety disorder. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1080099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comrey, A.L.; Lee, H.B. A First Course in Factor Analysis, 2nd ed.; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallit, S.; Obeid, S.; Sacre, H.; Akel, M.; Khoury, A.; Salameh, P. Adaptation of the Young Adults’ Cigarette Dependence (YACD) Scale for the development and validation of the Adolescent Cigarette Dependence Scale (ACDS). Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 28407–28414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, A.; Tang, L.; Hao, Y. Can Corporate Social Responsibility Promote Employees’ Taking Charge? The Mediating Role of Thriving at Work and the Moderating Role of Task Significance. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 613676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Pomerantz, E.M.; Chen, H. The role of parents’ control in early adolescents’ psychological functioning: A longitudinal investigation in the United States and China. Child Dev. 2007, 78, 1592–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, J.; Gao, Q.; Wu, R.; Ying, J.; You, J. Parental psychological control, Parent-Related loneliness, depressive symptoms, and regulatory emotional Self-Efficacy: A moderated serial mediation model of nonsuicidal Self-Injury. Arch. Suicide Res. 2021, 26, 1462–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, X.; Wu, J.; Guo, Z.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Zhao, Y.; Kou, Y. Parental psychological control and adolescents’ problematic mobile phone use: The serial mediation of basic psychological need experiences and negative affect. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2022, 31, 2039–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, C.F.; Wang, S.J.; Juang, K.D.; Fuh, J.L. Use of the Chinese (Taiwan) version of the Social Phobia Inventory (SPIN) among early adolescents in rural areas: Reliability and validity study. J. Chin. Med. Assoc. 2009, 72, 422–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connor, K.M.; Davidson, J.R.; Churchill, L.E.; Sherwood, A.; Foa, E. Psychometric properties of the Social Phobia Inventory (SPIN). New self-rating scale. Br. J. Psychiatry 2000, 176, 379–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajure, M.; Abdu, Z. Social Phobia and Its Impact on Quality of Life among Regular Undergraduate Students of Mettu University, Mettu, Ethiopia. Adolesc. Health Med. Ther. 2020, 11, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, J.; Zhou, Z.K.; Chen, W.; You, Z.Q.; Zhai, Z.Y. Development of the mobile phone addiction tendency scale for college students. Chin. Ment. Health J. 2012, 26, 222–225. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, G.; Tan, G.X.; Li, Y.X.; Liu, H.Y.; Wang, S.T. Physical exercise decreases the mobile phone dependence of university students in china: The mediating role of Self-Control. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, K.S. Internet addiction: The emergence of a new clinical disorder. Cyberpsychol. Behav. 1998, 1, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, P.; Fard, Z.; Pouravari, M. Predictive Role of Parental Acceptance, Rejection and Control in the Internet Addiction of the female students. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 2015, 2, 42–51. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.; Lee, K.; Yi, S.; Park, H.J.; Hong, Y.; Cho, H. Effects of Parental Psychological Control on Child’s School Life: Mobile Phone Dependency as Mediator. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2015, 25, 407–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschi, T. Causes of Delinquency; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Viejo, C.; Gomez-Lopez, M.; Ortega-Ruiz, R. Adolescents’ psychological Well-Being: A multidimensional measure. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nie, T.; Hu, G.; Qiu, T. Parental Control and College Students’ Adversarial Growth: A Discussion on Chinese One-Child Families. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Z.; Li, M.; Wu, J.; Li, X. Differential associations between parents’ versus children’s perceptions of parental socialization goals and chinese adolescent depressive symptoms. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 681940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.; Morris, A.S.; Criss, M.M.; Houltberg, B.J.; Silk, J.S. Parental psychological control and adolescent adjustment: The role of adolescent emotion regulation. Parent. Sci. Pract. 2014, 14, 47–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, I.; Vansteenkiste, M.; Soenens, B. The relations of Arab Jordanian adolescents’ perceived maternal parenting to teacher-rated adjustment and problems: The intervening role of perceived need satisfaction. Dev. Psychol. 2013, 49, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rote, W.M.; Olmo, M.; Feliscar, L.; Jambon, M.M.; Ball, C.L.; Smetana, J.G. Helicopter parenting and perceived overcontrol by emerging adults: A family-level profile analysis. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2020, 29, 3153–3168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luebbe, A.M.; Tu, C.; Fredrick, J.W. Socialization Goals, Parental Psychological Control, and Youth Anxiety in Chinese Students: Moderated Indirect Effects based on School Type. J. Youth Adolesc. 2018, 47, 413–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daraj, L.R.; AlGhareeb, M.; Almutawa, Y.M.; Trabelsi, K.; Jahrami, H. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Correlation Coefficients between Nomophobia and Anxiety, Smartphone Addiction, and Insomnia Symptoms. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.L.; Sheng, J.R.; Wang, H.Z. The Association Between Mobile Game Addiction and Depression, Social Anxiety, and Loneliness. Front. Public Health 2019, 7, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Yang, J.; Liu, L. Social Anxiety and Internet Addiction among Rural Left-behind Children: The Mediating Effect of Loneliness. Iran. J. Public Health. 2017, 46, 1659–1668. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Davis, R.A. A cognitive–behavioral model of pathological Internet use. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2001, 17, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Xu, Y.; Chen, X. How does self-esteem affect mobile phone addiction? The mediating role of social anxiety and interpersonal sensitivity. Psychiatry Res. 2019, 271, 526–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De-Sola, J.; Talledo, H.; Rubio, G.; de Fonseca, F.R. Psychological Factors and Alcohol Use in Problematic Mobile Phone Use in the Spanish Population. Front. Psychiatry 2017, 8, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cougle, J.R.; Wilver, N.L.; Day, T.N.; Summers, B.J.; Okey, S.A.; Carlton, C.N. Interpretation bias modification versus progressive muscle relaxation for social anxiety disorder: A Web-Based controlled trial. Behav. Ther. 2020, 51, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darcin, A.E.; Kose, S.; Noyan, C.O.; Nurmedov, S.; Yilmaz, O.; Dilbaz, N. Smartphone addiction and its relationship with social anxiety and loneliness. Behav. Inform. Technol. 2016, 35, 520–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhitomirsky-Geffet, M.; Blau, M. Cross-generational analysis of predictive factors of addictive behavior in smartphone usage. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 64, 682–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roos, L.E.; Salisbury, M.; Penner-Goeke, L.; Cameron, E.E.; Protudjer, J.L.P.; Giuliano, R.; Afifi, T.O.; Reynolds, K. Supporting families to protect child health: Parenting quality and household needs during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0251720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.Y.; Chou, W.H. A Bibliometric Analysis to Identify Research Trends in Intervention Programs for Smartphone Addiction. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartanto, A.; Quek, F.; Tng, G.; Yong, J.C. Does Social Media Use Increase Depressive Symptoms? A Reverse Causation Perspective. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 641934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo Cascio, V.; Guzzo, G.; Pace, F.; Pace, U.; Madonia, C. The relationship among paternal and maternal psychological control, self-esteem, and indecisiveness across adolescent genders. Curr. Psychol. 2016, 35, 467–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).