Abstract

Social media has a very important role in adolescents’ daily life, providing them with means for communicating, sharing, representing themselves and creating and maintaining relationships. However, social media can hide risks for the users which can undermine their mental well-being, especially amongst adolescents. The exploratory research presented in this paper aims at highlighting the relationships between the conscious use of social media by adolescents and their psychological well-being. In particular, we present a pilot study involving N = 80 adolescents (age 16–20), which was designed to analyse the constructs of mental well-being, life satisfaction and resilience in relation to the capacity of adolescents to use social media. Adolescents were randomly divided into an experimental group and a control group. The experimental group attended a social media literacy course aimed at raising participants’ awareness of the benefits and pitfalls of social media. The Mann–Whitney U test has been used to assess statistically significant differences between the two groups with respect to the age and the constructs under investigation. However, the test reported no statistically significant values (p > 0.05). We argue that statistically significant differences could be observed by involving a larger sample size. This seems to be confirmed by the low value of the power of the a posteriori test for all the variables considered. In this sense, our pilot study paves the way for new research aimed at investigating the impact of Social Media Literacy on adolescents’ psychological well-being.

1. Introduction

Media literacy is the ability to access, analyse, construct and evaluate media content in all its forms. According to Dieter Baacke [1], among the competencies related to media literacy that adolescents should acquire, there is the ability to reflect on the content and analyse them critically, also recognising the dangers of new communication technologies or social media. The use of smartphones and tablets has exacerbated the use of social media by adolescents. According to Censis 2022 statistics, Italian adolescents spend even more time than adults on social media. Adolescents aged 13 to 18 average 3 h and 1 min a day. Some teens, however, spend up to 9 h a day on social media, far more time than they spend in school. It is estimated that 330 million people will potentially suffer from Internet addiction in the coming years. In particular, adolescents spend most of their time interacting with different types of media, especially on social media platforms. The development of social media literacy provides an approach to increase awareness of the use of social media platforms and protect people from the negative influences of social media. To date, the best-known credited definition of social media is the one proposed by Kaplan and Haenlein (2010) [2], who define social media as “a group of Internet-based applications that form the ideological and technological foundations of Web 2.0 and enable the creation and exchange of user-generated content”. Social media platforms have deeply changed communication, information sharing and connections with others. While these platforms offer numerous benefits, they also pose potential risks, especially for adolescents [3]. Thus, social media literacy becomes crucial to empower young individuals in navigating the intricate digital landscape safely and responsibly. Social media literacy encompasses more than just knowing how to use platforms like Snapchat and Instagram; it involves using these platforms positively and responsibly. Understanding the subtleties of social media, such as privacy settings, etiquette and the consequences of online actions, is essential. Social media literacy goes beyond mere platform usage; it involves fostering critical thinking skills to evaluate online information accurately [4]. Developing social media literacy is particularly vital for children as it helps them mitigate potential risks associated with the online world. Consequently, over the past few years, there has essentially been an increasing interest in social media literacy, which has led to exploring its potential for developing critical skills and empowerment of individuals, with particular respect to adolescents. They are influenced, very frequently, in their intellectual, emotional and social life, affecting also important elements that interfere with the construction of their own identity, their own models of health and well-being and social behaviour.

The living environment of adolescents is the privileged place for observing individual differences and emotional and social-relational skills [5,6]. The interaction between the individual and the environment is essential to understand the development trajectories of individuals and above all to understand how to carry out developmental tasks. Indeed, from the perspective of developmental lifespan psychology, developmental tasks are different for each stage of the life cycle [7,8]. In particular, the developmental tasks of the adolescent concern the increase of personal, social and relational interests, the construction of identity, the formation of personality characteristics and motivational–emotional aspects [9].

The environments in which adolescents carry out developmental tasks can be both real and virtual such as the world of social media [10,11]. Social media respond to adolescents’ need for friends, events and emotions, to establish new relationships and strengthen social bonds with peers [7]. Social media offers adolescents a plurality of tools to communicate and manage their interpersonal relationships [8]. For adolescents, it is important to communicate and participate in social life through the establishment of relationships with peers [6,12].

However, other studies [13,14,15] highlighted how the meaning and nature of relationships are altered within social media environments, where the distinction between physical and virtual is blurred. Furthermore, adolescents are more exposed to social media threats, since they are unable to perceive the profoundly different dynamics that govern offline and online networks. In this perspective, social media constitute a fully fledged “place” to live in, and social media literacy can help adolescents to better live in this environment. In fact, social media literacy provides adolescents with specific tools to support a conscious use of social media environments [16].

1.1. Strengths and Risk Factors in Social Media Use

The term social media refers to web platforms whose main function is to create a network of online relationships. Well-known examples of social media are Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Linkedin, MySpace and Tik Tok [11,17]. In these virtual networks, young people create personalised profiles that they use to express themselves, exchange information, share images and videos and socialise [18]. Each user can develop their own network of contacts and manage the privacy setting [5]. Social media have revolutionised the communication paradigm because they allow a person to communicate at different levels and with different people [5,10,19,20].

With the advent of the so-called Web 2.0, the boundaries between the roles of content creators and surfers are blurred, raising the level of the “surfer” to a “social user” interacting, participating and sharing [5]. In general, “interacting” indicates an action that influences other actions. In the context of social media, the types of actions can be various such as commenting on an image uploaded by another user or replying to an existing comment [6,10]. Participation is another important aspect of social media environments. It refers to the possibility for the users to contribute to social relationships and feel part of an online group [8,20,21,22]. In the context of social media, expressing individuals’ interests (for example by assigning likes to content) has the consequence of establishing relationships with other users with common interests [21]. Even membership in a specific social media is a sign of participation. There are no other means of communication that gives as equal importance to the identity of the individual as social media. Obviously, the use of social media is not exempt from risks [13,14,23,24,25,26,27,28].

The most widespread problems of social media are the pervasive spread of disinformation and misinformation, and the growing trend of hateful practices [6]. Even though social media platforms feature official policies that ban hate speech and discrimination, these new media have nonetheless proved powerful tools for reaching new audiences and building communities for inciting hatred and discrimination [22,29]. The consequences of this behaviour can be dramatic since content that incorporates violence not only produces negative effects on users but also makes them dysfunctional [19,20,21].

Artificial Intelligence techniques implementing specific social media mechanisms, such as recommendation systems, can filter the content the users are exposed to. Consequently, polarisation, radicalisation and the creation of filter bubbles and echo chambers [30] produce serious risks for social media users.

The search for friendships in social media offers adolescents opportunities for new relations but, at the same time, it exposes them to risky interactions [5,10,31].

Several psychological and educational studies on the Internet and, in particular on the use of social media, have focused on the phenomenon of Internet addiction [10,32,33,34,35,36].

The uncontrolled use of social media is often linked to a lack of awareness on the part of adolescents [19,32,33,37,38]. Therefore, it is extremely important to support adolescents in a critical approach to their use, especially highlighting their role as tools to promote sociality but not as an ultimate goal for building relationships [21]. It is essential to develop an awareness of the strengths and weaknesses of social media. Biolcati shows a lack of digital awareness on the part of adolescents relating to the critical recognition of websites, the awareness of the commercial mechanisms that make up the web economy and the assessment of the level of reliability of content [10]. Consequently, adolescents are becoming assiduous navigators of the Internet and frequent social media users, but they demonstrate a wealth of knowledge that is not always adequate for a conscious experience [10,32,37]. If we also consider the risks associated with navigation from the point of view of interaction with other people whose identity can be easily masked by the Internet, we agree with Cappuccio and Compagno [11] and that school and family support in the using Internet environments is an urgent and demanding challenge.

The risks reported in this section represent a threat to different individual factors such as mental well-being, life satisfaction and resilience [39,40].

1.2. From Positive Mental Health to Conscious Use of Social Media

There is an increasing interest in the concept of positive mental health and its influence on all aspects of human life. The World Health Organization has declared positive mental health to be the foundation for well-being and effective functioning for both the individual and the community and defined it as a state which allows individuals to realise their abilities, cope with the normal stresses of life, work productively and fruitfully and make a contribution to their community [41]. The ability to maintain mutually satisfying and enduring relationships is another important aspect of each individual’s positive mental health, in particular, adolescents [21].

Teens are constantly looking for effective, meaningful and lasting relationships. In particular, adolescents use the world of social media to maintain and enforce existing relationships and search for new and interesting friends, relationships and models to follow [42,43]. Furthermore, by considering that the concept of positive mental health is influenced by personal life experiences wherever they occur, thus including both real and virtual places, social media must be taken into account when analysing the elements that influence positive mental health [44,45].

Accordingly, in the pilot study presented in this paper, we analyse the constructs of mental well-being, life satisfaction and resilience in social media environments. These constructs are important in intra and interpersonal relationships and promote the concept of positive mental health [7,40,46,47].

Adolescents need to learn how to use the world of social media that attracts them and at the same time engages them without being aware of the risks [48].

Some adolescents reach a phase of equilibrium, characterised by responsible use of the Internet and integrated with “real life” activities [13,14,23,24,25,26,27,28]. Unfortunately, this equilibrium is not reached by all adolescents, and therefore, specific guidance is necessary for inexperienced users to approach the world of the internet and social media consciously [46].

The purpose of the pilot study presented in this paper is to highlight the role of a specific training school activity which can encourage a fair and safe use of social media in adolescents in relation to the constructs of mental well-being, life satisfaction and resilience of the adolescents involved in the pilot [1,49,50].

2. Materials and Methods

We conducted a pilot study divided into two phases. In the first phase (Phase 1) a training school activity (TSA) promoting and supporting constructive use of social media was carried out in adolescents belonging to the experimental group (EG). In particular, the training activity has aimed at mitigating social media risks, such as disinformation and misinformation, echo chambers and filter bubbles and improper use of Artificial Intelligence algorithms. The TSA has been divided into six weekly sessions, run for six consecutive weeks and for 30 h in total. Because of the COVID-19 lockdown, all the sessions have been directed and coordinated online.

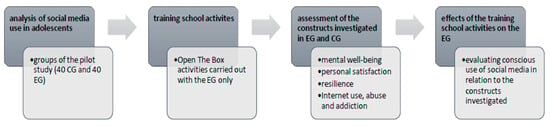

The second phase (Phase 2) consisted of an assessment procedure aimed at analysing the psychological characteristics of adolescents (in particular, mental well-being, life satisfaction and resilience) in correlation with social media use, The assessment has been carried out with both the experimental group and the control group (CG), through questionnaires created and administered via the Google forms service. Figure 1 shows the model and the procedure for the analysis of social media use in adolescents, with a comparison between the experimental group and the control group.

Figure 1.

Description of the pilot study model and procedure.

2.1. Participants

Participants are adolescents who were recruited in two secondary schools in the city of Palermo in Italy. Experimental group includes n = 40 adolescents (25 male, 15 female, age range = 18.18 years; SD = 0.781). Control group includes adolescents n = 40 adolescents (25 male, 15 female, age range = 17.94 years; SD = 0.791).

Participants, predominantly Italian, were randomly assigned to the experimental and control groups and had a random assignment distribution generated by a computer procedure. It is a convenience sample. Before starting the training school activity (TSA), we administered a questionnaire to gather personal information (age and sex). In addition, each student was assigned an alphanumeric identification code which they used for each activity of the training activities and during the administration of the questionnaires. In such a way, we have removed the personal information of the participants to guarantee the privacy policies and avoid identification of the subjects.

2.2. Materials

We have used two different types of material in this pilot study: the Open the Box platform in Phase 1, and some questionnaires and scales used for the assessment in Phase 2.

2.2.1. Intervention

The Open the Box platform is a media and data literacy digital platform, designed and developed by the Italian media company Dataninja. The main goal of the platform is mitigating the effects of digital misinformation, through a “constructive” and long-term approach: attracting, training and empowering a community of young “data-checkers” involving schools, non-profits and other educational institutions.

To carry out the training school activity, we designed ad hoc interactive lessons based on the Open the Box platform.

Open the Box is one of the first educational projects to mix together media and data literacy approaches. As seen during the COVID-19 pandemic, data are becoming more and more central in our political and civic life; understanding how data work and how they can be used in a manipulative way is crucial for all citizens and decision-makers. For these reasons, Open the Box promotes well-known media literacy skills (like source-checking and manipulated image spotting) together with less-known data literacy skills, such as analysing how visualisations can “lie” and understanding how artificial intelligence works.

The primary target of Open the Box are teachers, educators and other professionals involved in educational activities with 13–18 years old adolescents, in both formal and informal contexts. Teachers and educators can get access to free-to-use materials available on the Open the Box platform, which includes self-training resources and 10 interactive lessons.

The secondary target of Open the Box is adolescents involved by teachers and educators. Adolescents are engaged through several interactive activities (quizzes, group activities and interactive assessments) and a final open challenge. During the challenge, they are invited to identify a piece of disinformation online (it could be “false” news, a social media post, a video or data visualisation) to verify it using the skills and tools learned during the lessons and to work on a new piece of debunking content to be shared among their peers on social networks.

Open the Box aims not only to upgrade educators and students’ digital skills but also to invite them to become more active and responsible in promoting better information practices in their social contexts.

At the core of Open the Box are three main theoretical approaches:

- Ecological thinking: “to encourage reflection about how deeply entwined we are with our environment and with each other” [51]; in this definition, “environment” should be intended in its broader meaning (e.g., the digital environment);

- Hacking culture: “to think just as much about how you build an ideal system as how it might be corrupted, destroyed, manipulated, or gamed. Think about unintended consequences, not simply to stop a bad idea but to build resilience into the model” [52,53].

- Design principles: “Data literacy tools and activities that support learners must be focused, guided, inviting and expandable” [54].

Synthesising these rich theoretical approaches, Open the Box makes available a set of free materials and resources. Educators can use these materials in their everyday activities, through a suggested five-step educational format: (1) students are engaged on the topic with an interactive quiz; (2) the educator explains to them how they could better explore the digital news ecosystem and which tools could be useful; (3) students are divided into small groups and invited to conduct an online investigation; (4) students are invited to fill an evaluation test to assess their skills; (5) students can participate to an open challenge to produce original fact-checking content.

As for content, Open the Box presents 3 main learning paths: (a) Disinformation and fact-checking; (b) social media; (c) Artificial Intelligence. Each learning path proposes 3 or 4 interactive lessons on the following topics: “false” news, manipulated images, data and graphics (path a); meme culture, viral dynamics and digital relationships (path b); deepfakes and synthetic media, bot and automated content, filter bubble and algorithmic recommendations (path c).

Open the Box should be considered as a concept that, starting from a solid theoretical background, integrates educational methodologies and materials. Therefore, it represents valid support for the design of the school training activity that has been run during Phase 1.

2.2.2. Measures

The questionnaires and scales for the assessment of the investigated constructs used in Phase 2 are the UADI Questionnaire—Internet Use, Abuse and Addiction [39]; the Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (WEMWBS) [22]; the Satisfaction with life scale [36]; the Adolescent Psychological Resilience Scale (APRS) [55].

The UADI Questionnaire has been administered to analyse the processes underlying social media use. In particular, the questionnaire reveals psychological and psychopathological variables related to the use of the Internet. It consists of 80 items on a five-point Likert scale structured in five dimensions: Compensatory Escape (EVA), Dissociation (DIS), Real Life Impact (IMP), Experience Making (SPE) and Addiction (DIP). The Compensatory Escape (EVA) section of the questionnaire analyses the use of the Internet in terms of evasion, as an act of compensation with respect to the difficulties of real daily life. The items concern the positive regulation of mood, the sense of personal competence and the quality of social relations. The items of the Dissociation (DIS) dimension investigate some dissociative symptoms (bizarre sensory experiences, depersonalisation and derealisation) together with the tendency to alienation and distance-escape from reality. The Real-Life Impact (IMP) section explores the consequences of the use of the Internet in real life (possible changes in habits, social relationships and mood). The items of the Experience Making (SPE) dimension consider the use of the Internet as a private space, as a social laboratory for self-experimentation, as a playground and regression, and as a tool for the search for emotions. Finally, the Addiction (DIP) section of the questionnaire concerns behaviours and symptoms associated with addiction, in particular, tolerance (progressive increase in the connection period), abstinence, compulsivity and hyper-involvement.

The Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (WEMWBS) measures the determinants of mental well-being through a 14-item scale. WEMWBS has 5 response categories, which are summed up to provide a single score. The items are all worded positively and cover both feeling and functioning aspects of mental well-being.

The Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS) has proved to be a valid and reliable measure of life satisfaction, suited for use with a wide range of age groups and applications. The 5-item SWLS has 5 response categories, summed up to provide a single score. The items are all worded positively and cover different aspects of life satisfaction.

The Adolescent Psychological Resilience Scale (APSR) analyses the concept of psychological resilience mechanism basically consisting of internal and external support sources, characterised by six dimensions. The dimensions concern family, friends, school support, adjustment, sense of struggle and empathy. The items related to the Family Support (FS) dimension are related to the communication in the family and the support given to the adolescent by the family. The Confidant-Friend Support (CFS) dimension investigates how friends and confidants sustain the adolescent. School Support (SS) is related to the support given to the adolescent by teachers and school staff members. Adjustment (A) is related to the adolescent’s ability to adapt to new life conditions. The items of the Sense of Struggle (SoS) dimension are related to the adolescent’s having a future target that includes a sense of struggle. Finally, Empathy (E) items are related to the adolescent’s ability or tendency to understand other people.

All the scales used in these questionnaires are Likert scales that range from a lower to a higher value indicating, respectively a fewer and higher presence of the investigated constructs.

2.3. Analysis

A univariate descriptive analysis of the variables under study was carried out by calculating the centrality and variability indices for the quantitative variables and frequency table for the qualitative variables. The descriptive analysis was made according to the distinction between the two groups: experimental group and control group (Table 1).

Table 1.

Descriptive analysis of the experimental group (EG) and the control group (CG), p-value of Mann–Whitney U Test. PF: UADI Questionnaire and APSR: Adolescent Psychological Resilience Scale.

Specific statistical tests have been used to assess whether statistically significant differences between the two groups emerge. In particular, the Mann–Whitney U test has been adopted for the age variable and for the quantitative variables.

Furthermore, we have analysed the post hoc power test to assess whether the sample size is such as to ensure that, when the null hypothesis is false it is correctly rejected.

In all the analyses mentioned above, an alpha significance level of 0.05 was used. IBM SPSS Statistics software in version 25 was used for the statistical analysis of data. Descriptive statistics for quantitative variables and frequency tables for nominal variables are presented below for the two groups (experimental and control).

3. Results

The dataset is made up of 80 sample units, divided into two randomised groups of adolescents: control group and experimental group. Each group is made up of 40 adolescents, 25 of them are males and 15 females. In this analysis, all 80 sample units were considered.

The Mann–Whitney U test has been used to assess statistically significant differences between the two groups with respect to age and the other dataset variables.

Considering the variable age in the two groups, as reported in Table 1, it has been observed that the p-value is not statistically significant (p = 0.850). Consequently, we accept the null hypothesis and conclude that the age appears to be homogeneous in the two groups.

Considering all the other variables of the dataset, it has been observed that also in this case, the p-values of all the Mann–Whitney U tests are not statistically significant (p > 0.05) Nevertheless, it should be verified the hypothesis that, in the presence of a larger sample size, statistically significant differences could be observed between the two groups.

In all these cases, we accept the null hypothesis and conclude that the distribution of the values of the variables considered is not significantly different between the experimental and control groups.

In the post hoc power test as reported in the previous section, the analysis of the data shows that the differences are not significant. This result has suggested the calculation of the post hoc power test to improve our data interpretation.

In this study the post hoc power test has been carried out on a sample of 80 participants, assuming an alpha level equal to 0.05. To estimate the power, for each variable the sample means, the sample standard deviations and the number of participants in the two groups have been used, together with the level of significance.

The post hoc power test has been calculated through the tool made available on the website www.clincalc.com (accessed on 16 April 2021), and the results for all variables are reported in Table 2.

Table 2.

Post hoc power test for the variables under investigation. PF: UADI Questionnaire, APSR: Adolescent Psychological Resilience Scale.

The calculated powers of the post-tests show rather low values, with the highest values for PF DIP, PF SPE and PF IMP (respectively, 26.7%, 25.7% and 26.9%), which are, however, not high enough.

Consequently, by taking into account that low values of the test power equate to high values of beta, where beta is the probability of accepting the null hypothesis when it is, in fact, false, we cannot exclude to be in presence of a false negative or type II error (not reject the null hypothesis when there is a significant effect).

4. Discussion

The pilot study presented in this paper represents exploratory research, from which further investigation on methods for social media literacy aimed at promoting the conscious use of social media amongst adolescents should be done. The results of the pilot study have not highlighted statistically significant differences for the investigated constructs between the group of students who attended the training session and the control group. However, having found a low power of the a posteriori test for all the variables describing the constructs, we argue that it would be possible to have significant results by increasing the sample size. In fact, generally, a low number of participants could give rise to the possibility of selection bias and low generalisability of results, but in our pilot, it was not possible to involve a larger number of students because of the COVID-19 pandemic emergency and the necessity to run all the activities online [1,49,50].

We cannot be sure that the non-significance of the differences may be due solely to the insufficient sample size. Rather, further research is necessary for a more rigorous evaluation of the effectiveness and efficacy of the tools used in the intervention and assessment phases of the pilot. An important future research perspective will consider the use of the American Psychological Association’s Evidence-Based Practice (EBP) methodology [56] to validate the training model proposed in this pilot study and the research method itself. EBP highlights the importance of the experimentation context as a key factor to demonstrate the effectiveness of an intervention [56,57].

EBP is embodied in the translational psychology research area, in which theoretical and practical aspects are intertwined not only to analyse the difficulties of a person but also to guide the design of interventions that integrate basic research and applied research. EBP originates in the clinical psychology area, but it is receiving increasing attention in school psychology [57]. In this sense, our pilot study is an example of training that could be replicated on the basis of Evidence-based practice. Repeating this study with a larger sample and following the EBP method could guarantee more significant results and the consequent possibility of having an effective and efficient training research method to replicate. A new trial with an increased number of students randomly selected from different schools is already planned [11,49].

The use of social media is first and foremost a process that generates changes and that leads to the acquisition of new knowledge and relationships especially for adolescents. Learning to act on the consequences of the indiscriminate use of social media for adolescents means acting indirectly on a set of psychological tasks. Although developmental tasks are shared by all adolescents, numerous factors can play a role in defining how these tasks are performed. Therefore, the importance given to social media in communication between adolescents is increasingly relevant. Social media, in fact, assert themselves among adolescents as channels for building relationships and are often the main communication channel and the privileged place to carry out developmental tasks [8,20].

However, as highlighted in this paper, social media are often fraught with dangers. Resolving the tension between these opposing perspectives on social media is an urgent challenge. Therefore, supporting adolescents, in a conscious and careful use of social media is a way to support their development and in particular their behaviour, thought, emotions and actions. Even though statistics have not proved the effectiveness of the pilot study, we argue that training school activities is essential to promote mutual listening and attention to respect social rules in social media.

The hypothesis Is that the EG benefited from the training as it promoted analytical thinking in adolescents. According to the literature, this type of training enhances analytical thinking [4]. The conscious use of social media is linked to moral disengagement and analytical thinking. For example, studies on moral disengagement refer to the process whereby individuals or groups deviate from normal or usual ethical standards due to perceived circumstances. Adolescents on social media often justify new non-ethical behaviours under such circumstances, viewing their virtual life as separate from real life and deeming ethical behaviour unnecessary. The moral disengagement process is often necessary for implementing non-ethical behaviours, such as using hostile language on social media [58,59,60].

Training adolescents to develop analytical thinking can help resolve moral disengagement. Indeed, it may prevent the low propensity toward analytical thinking that arises when adolescents are exposed to social media [61]. The training proposed in this study supports analytical thinking by countering negative stimuli encountered by adolescents during technological interactions, including social media. Research by Paol and Elder aimed to address prejudices and cognitive distortions on social media among young people by inducing analytical thinking [4]. The authors argue that analytical thinking, supported by a willingness to engage in deliberate reasoning, can reduce behaviours supporting socio-cognitive processes that justify aggression and bullying. To promote analytical reasoning, it is desirable to design training programs that require a greater commitment from adolescents. Further studies are needed to assess the effectiveness of such interventions, which aim to improve socio-analytical skills and can be easily implemented in the educational field. Educators and teachers can consider simple instructions to improve socio-analytical skills in adolescents, such as specific procedures proposed for reading and rewriting misleading news [62]. The users tend to avoid misinformation but still share inaccurate news due to factors like political opinions rather than accuracy [63]. Building upon these theoretical foundations, Lutzke and colleagues emphasised the importance of guidelines to evaluate online news, which can promote analytical thinking when people are exposed to false information [64]. Such guidelines could greatly assist teenagers in discerning between credible and misleading content on social media.

This study represents a starting point for future investigations in this field with useful implications for schools, teachers and young people. Personal and contextual factors are closely intertwined, outlining development paths with very different outcomes [65,66].

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, L.S., D.T. and G.F.; methodology, L.S.; software, N.B.; formal analysis, L.S., D.T. and G.F.; investigation, D.T. and L.S. data curation, L.S.; writing—original draft preparation, G.F. and D.T.; writing—review and editing, G.F. and D.T.; supervision, G.F. and D.T.; project administration, D.T.; funding acquisition, D.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work has been developed in the framework of the project COURAGE—A social media companion safeguarding and educating students (No. 95567), funded by the Volkswagen Foundation on the topic of Artificial Intelligence and the Society of the Future.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Institute for Educational Technology, National Research Council of Italy, Italy. Ethics Committee Name: ethical evaluation by the Institute of Educational Technologies (ITD-CNR), has viewed and analysed the nature, objectives and methods of carrying out the European project “COURAGE: A Social Media Companion Safeguarding and Educating Students”. Approval Code: AMMCNT-CNR n. 0065527/2019. Approval Dates: 14 June 2021.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Acknowledgments

The authors are particularly grateful to the school involved in the experimentation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Baacke, D. Die Welt der Musik und die Jugend Eine Einleitung. In Handbuch Jugend und Musik; Baacke, D., Ed.; VS Verlag für Sozi-alwissenschaften: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, A.M.; Haenlein, M. Users of the world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of Social Media. Bus. Horiz. 2010, 53, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulantelli, G.; Taibi, D.; Scifo, L.; Schwarze, V.; Eimler, S.C. Cyberbullying and Cyberhate as Two Interlinked Instances of Cyber-Aggression in Adolescence: A Systematic Review. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 909299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, R.; Elder, L. The Thinkers Guide for Conscientious Citizens on How to Detect Media Bias and Propaganda in National and World News: Based on Critical Thinking Concepts and Tools; Rowman & Littlefield: Lanham, MD, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Avena, G. I comportamenti relazionali nell’era dei social network: Indagine sull’utilizzo di Facebook tra gli adolescenti di una comunità scolastica. Humanities 2020, 6, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michikyan, M.; Suárez-Orozco, C. Adolescent Media and Social Media Use: Implications for Development. J. Adolesc. Res. 2016, 31, 411–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Best, P.; Manktelow, R.; Taylor, B. Online communication, social media and adolescent wellbeing: A systematic narrative review. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2014, 41, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compagnone, M. Adolescenti & Social. Vivere «Disincantati» Nel Tempo Dell’immagine; Booksprint: Buccino, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Fonzi, A. Manuale di Psicologia dello Sviluppo; Giunti: Firenze, Italy, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Biolcati, R. La Vita Online degli Adolescenti: Tra Sperimentazione e Rischio; Il Mulino: Bologna, Italy, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Cappuccio, G.; Compagno, G. L’illusione del sapere: L’universo delle fake news. un’indagine esplorativa con gli adolescenti. MeTis 2020, 10, 210–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subrahmanyam, K.; Reich, S.M.; Waechter, N.; Espinoza, G. Online and offline social networks: Use of social networking sites by emerging adults. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2008, 29, 420–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livingstone, S.; Haddon, L.; Görzig, A.; Ólafsson, K. Risks and Safety on the Internet: The Perspective of European Children; Full Findings; EU Kids Online, LSE: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Staksrud, E.; Ólafsson, K.; Livingstone, S. Does the use of social networking sites increase children’s risk of harm? Comput. Hum. Behav. 2013, 29, 40–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willoughby, M. A review of the risks associated with children and young people’s social media use and the implications for social work practice. J. Soc. Work. Pract. 2019, 33, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulantelli, G.; Scifo, L.; Taibi, D. Training School Activities to Promote a Conscious Use of Social Media and Human Development According to the Ecological Systems Theory. In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2021), Online, 23–25 April 2021; pp. 517–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biolcati, R.; Cani, D.; Badio, E. Adolescenti e Facebook: La gestione online della privacy. Psicol. Clin. Svilupp. 2013, 17, 491–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milani, L. “Like me”-Il ruolo dei social media nelle relazioni sentimentali degli adolescenti. In Questioni di Cuore. Le Relazioni Sentimantali in Adolescenza: Traiettorie Tipiche e Atipiche; Confalonieri, M.G.O.E., Ed.; Unicopli: Milano, Italy, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal, S.; Awekar, A. Deep Learning for Detecting Cyberbullying Across Multiple Special Media Platforms. In Advances in Information Retrieval. ECIR 2018. Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Pasi, G., Piwowarski, B., Azzopardi, L., Hanbury, A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, C.T.; Sidoti, C.L.; Briggs, S.M.; Reiter, S.R.; Lindsey, R.A. Adolescent social media use and mental health from adolescent and parent perspectives. J. Adolesc. 2017, 61, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pediconi, M.G.; Brunori, M. Affetti Nella Rete: Il Benessere degli Adolescenti Tra Rischi e Opportunità Social; Franco Angeli: Milano, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Tennant, R.; Hiller, L.; Fishwick, R.; Platt, S.; Joseph, S.; Weich, S.; Parkinson, J.; Secker, J.; Stewart-Brown, S. The Warwick-Edinburgh mental well-being scale (WEMWBS): Development and UK validation. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2007, 5, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovink, G. Ossesioni Collettive: Critica dei Social Media; Università Bocconi: Milano, Italy, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- March, E.; Marrington, J.Z. Antisocial and Prosocial online behaviour: Exploring the roles of the Dark and Light Triads. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 42, 1390–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascheroni, G. I Ragazzi e La Rete. La Ricerca EU Kids Online e Il Caso Italia; La Scuola: Brescia, Italy, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Mauceri, S. Adolescenti Interconnessi: Un’indagine Sui Rischi di Dipendenza da Tecnologie e Media Digitali; Armando: Roma, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- McCrae, N.; Gettings, S.; Purssell, E. Social Media and Depressive Symptoms in Childhood and Adolescence: A Systematic Review. Adolesc. Res. Rev. 2017, 2, 315–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mengu, S.; Mengü, S. Violence and Social Media. Athens J. Mass Media Commun. 2015, 1, 211–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slonje, R.; Smith, P.K.; Frisén, A. The nature of cyberbullying, and strategies for prevention. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2013, 29, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pariser, E. The Filter Bubble: What the Internet Is Hiding from You; Penguin UK: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lazzari, M. La comunicazione degli adolescenti in Rete tra opportunità, rischi, consapevolezza e fragilità. In Identità, Fragilità e Aspettative Nelle Reti Sociali Degli Adolescenti; Lazzari, M., Quarantino, M.J., Eds.; Sestante Edizioni: Bergamo, Italy, 2013; pp. 193–203. [Google Scholar]

- Cirillo, L.; Lancini, M. Il trattamento delle dipendenze da internet in adolescenza. Psichiatr. Apsicoterapia 2013, 32, 89–100. [Google Scholar]

- Cortoni, I.; Lo Presti, V. Social Network Addiction; Armando: Roma, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, P.; Wang, N.; Kong, L.; Dong, X.; Tian, L. A large number of online friends and a high frequency of social interaction compensate for each Other’s shortage in regard to perceived social support. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 42, 1575–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Paolo, V.; Miceli, S.; Monacis, L.; Sinastra, M. Dipendenze da internet e social media negli adolescenti: Il ruolo dei processi identitari. Psicol. Comunità 2016, 2, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Emmons, R.A.; Larsen, R.J.; Griffin, S. The Satisfaction with Life Scale. J. Personal. Assess. 1985, 49, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancini, M. Adolescenti Navigati; Centro Studi Erickson: Trento, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- O’reilly, M. Social media and adolescent mental health: The good, the bad and the ugly. J. Ment. Health 2020, 29, 200–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Miglio, C.; Gamba, A.; Cantelmi, T. Costruzione e validazione preliminare di uno strumento (U.A.D.I.) per la rilevazione delle variabili psicologiche e psicopatologiche correlate all’uso di internet Internet-related psychological and psychopathological variables: Construction and preliminary validation of the U.A.D.I. survey. J. Psychopathol. 2001, 7, 293–306. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, H.J.; Ozkaya, E.; LaRose, R. How does online social networking enhance life satisfaction? The relationships among online supportive interaction, affect, perceived social support, sense of community, and life satisfaction. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 30, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, J.; Balfour, R.; Bell, R.; Marmot, M.G. Social Determinants of Mental Health. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2014, 26, 392–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandri, M. La rappresentazione del ruolo di genere negli adolescenti attraverso i social media alcune osservazioni. Nuova Second. 2015, 5, 8–13. [Google Scholar]

- Tse, C.K.; Bridges, S.M.; Srinivasan, D.P.; Cheng, B.S. Social Media in Adolescent Health Literacy Education: A Pilot Study. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2015, 4, e3285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Moreno, M.; Uhls, Y.T. Applying an affordances approach and a developmental lens to approach adolescent social media use. Digit. Health 2019, 5, 2055207619826678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunstein, C.R. # Republic: Divided Democracy in the Age of Social Media; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Beyens, I.; Pouwels, J.L.; van Driel, I.I.; Keijsers, L.; Valkenburg, P.M. The effect of social media on well-being differs from adolescent to adolescent. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 10763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.M.; Amialchuk, A.; Rizzo, J.A. The influence of body weight on social network ties among adolescents. Econ. Hum. Biol. 2011, 10, 20–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattaro, C.; Setiffi, F. La socialità mediata: Strategie e modalità comunicative degli adolescenti tra online e offline. Comun. Soc. 2020, 1, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caso, D. L’uso di Internet e il benessere psicosociale in adolescenza: Uno studio correlazionale. Psicol. DELLA Salut. 2015, 2, 141–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheadle, J.E.; Schwadel, P. The ‘friendship dynamics of religion’, or the ‘religious dynamics of friendship’? A social network analysis of adolescents who attend small schools. Soc. Sci. Res. 2012, 41, 1198–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, W.; Milner, R. You Are Here: A Field Guide for Navigating Polarized Speech, Conspiracy Theories, and Our Polluted Media Landscape; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd, D. When Good Intentions Backfire… and Why We Need a Hacker Mindset, in Data & Society Points. 2017. Available online: https://points.datasociety.net/when-good-intentions-backfire-786fb0dead03 (accessed on 5 January 2017).

- Moriggi, S.; Pireddu, M. Vivere e non sapere. Fenomenologia della post-truth tra educazione e comunicazione./To live and not Know. The Phenomenology of Post-Truth between Education and Communication. Future Sci. Ethics 2017, 2, 96–105. [Google Scholar]

- D’Ignazio, C.; Bhargava, R. DataBasic: Design Principles, Tools and Activities for Data Literacy Learners. J. Community Inform. 2016, 12, 83–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulut, S.; Dogan, U.; Altundag, Y. Adolescent psychological resilience scale: Validity and reliability study. Suvremena Psihol. 2013, 16, 21–32. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association. Evidence-based practice in psychology. Am. Psychol. 2006, 61, 271–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canivez, G. Evidence-Based Assessment for School Psychology: Research, Training, and Clinical Practice. Contemp. Sch. Psychol. 2019, 49, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iannello, P.; Sorgente, A.; Lanz, M.; Antonietti, A. Financial Well-Being and Its Relationship with Subjective and Psychological Well-Being Among Emerging Adults: Testing the Moderating Effect of Individual Differences. J. Happiness Stud. 2021, 22, 1385–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cricchio, M.G.L.; Stefanelli, F.; Palladino, B.E.; Paciello, M.; Menesini, E. Development and Validation of the Ethnic Moral Disengagement Scale. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 756350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennycook, G.; Binnendyk, J.; Newton, C.; Rand, D.G. A Practical Guide to Doing Behavioral Research on Fake News and Misinformation. Collabra Psychol. 2021, 7, 25293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Llorente, A.M.P.; Gómez, M.C.S. Digital competence in higher education research: A systematic literature review. Comput. Educ. 2021, 168, 104212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’errico, F.; Cicirelli, P.G.; Corbelli, G.; Paciello, M. Addressing racial misinformation at school: A psycho-social intervention aimed at reducing ethnic moral disengagement in adolescents. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 2023, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennycook, G.; Epstein, Z.; Mosleh, M.; Arechar, A.A.; Eckles, D.; Rand, D.G. Shifting attention to accuracy can reduce misinformation online. Nature 2021, 592, 590–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lutzke, L.; Drummond, C.; Slovic, P.; Árvai, J. Priming critical thinking: Simple interventions limit the influence of fake news about climate change on Facebook. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2019, 58, 101964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulantelli, G.; Scifo, L.; Taibi, D. The Ecological Systems Theory of Human Development to Explore the Student-Social Media Interaction. In Proceedings of the 17th International Scientific Conference eLearning and Software for Education, Bucharest, Romania, 22–23 April 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, D.; Sikstrom, S. The dark side of Facebook: Semantic representations of status updates predict the Dark Triad of personality. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2013, 67, 92–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).