Self-Care Practices as a Mediator between Workaholism and Sleep–Wake Problems during COVID-19

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.3. Procedures

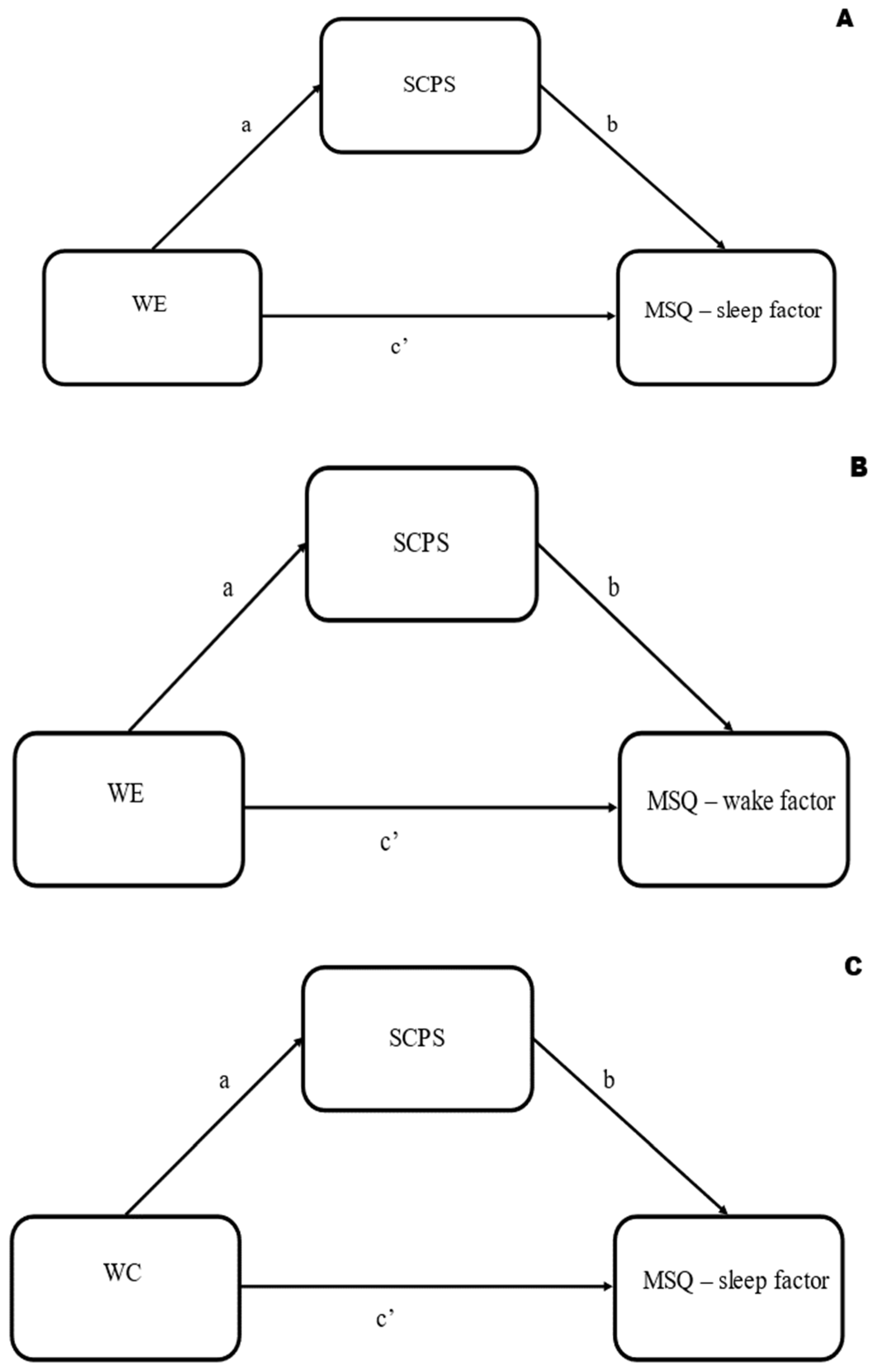

2.4. Data Analysis

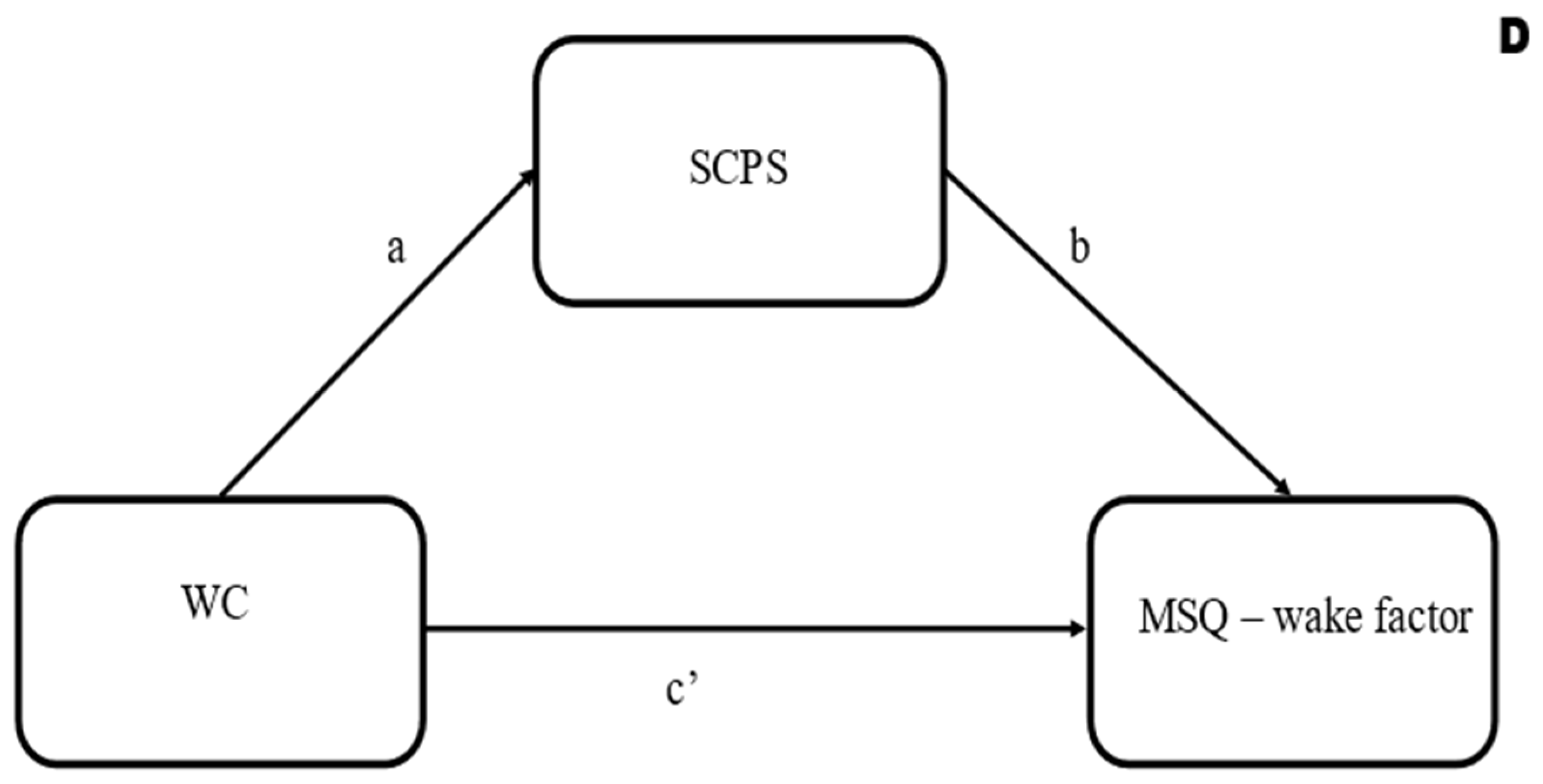

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Oates, W.E. On Being a “Workaholic” (A Serious Jest). Pastor. Psychol. 1968, 19, 16–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oates, W.E. Confessions of a Workaholic: The Facts about Work Addiction; World Publishing Company: New York, NY, USA, 1971; ISBN 978-0529006615. [Google Scholar]

- Snir, R.; Harpaz, I. Beyond Workaholism: Towards a General Model of Heavy Work Investment. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2012, 22, 232–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snir, R.; Harpaz, I. The Workaholism Phenomenon: A Cross-National Perspective. Career Dev. Int. 2006, 11, 374–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreassen, C.S.; Griffiths, M.D.; Hetland, J.; Kravina, L.; Jensen, F.; Pallesen, S. The Prevalence of Workaholism: A Survey Study in a Nationally Representative Sample of Norwegian Employees. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e102446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, M.A.; Michel, J.S.; Zhdanova, L.; Pui, S.Y.; Baltes, B.B. All Work and No Play? A Meta-Analytic Examination of the Correlates and Outcomes of Workaholism. J. Manag. 2016, 42, 1836–1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Taris, T.W.; Van Rhenen, W. Workaholism, Burnout, and Work Engagement: Three of a Kind or Three Different Kinds of Employee Well-Being? Appl. Psychol. 2008, 57, 173–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakanen, J.J.; Peeters, M.C.W.; Schaufeli, W.B. Different Types of Employee Well-Being across Time and Their Relationships with Job Crafting. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2018, 23, 289–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, M.A.; Smith, R.W.; Haynes, N.J. The Multidimensional Workaholism Scale: Linking the Conceptualization and Measurement of Workaholism. J. Appl. Psychol. 2020, 105, 1281–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balducci, C.; Avanzi, L.; Fraccaroli, F. The Individual “Costs” of Workaholism: An Analysis Based on Multisource and Prospective Data. J. Manag. 2018, 44, 2961–2986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillet, N.; Morin, A.J.S.; Cougot, B.; Gagné, M. Workaholism Profiles: Associations with Determinants, Correlates, and Outcomes. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2017, 90, 559–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Shimazu, A.; Taris, T.W. Being Driven to Work Excessively Hard: The Evaluation of a Two-Factor Measure of Workaholism in The Netherlands and Japan. Cross-Cult. Res. 2009, 43, 320–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimazu, A.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Kamiyama, K.; Kawakami, N. Workaholism vs. Work Engagement: The Two Different Predictors of Future Well-Being and Performance. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2015, 22, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimazu, A.; Schaufeli, W.B. Is Workaholism Good or Bad for Employee Well-Being? The Distinctiveness of Workaholism and Work Engagement among Japanese Employees. Ind. Health 2009, 47, 495–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molino, M.; Bakker, A.B.; Ghislieri, C. The Role of Workaholism in the Job Demands-Resources Model. Anxiety Stress Coping 2016, 29, 400–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andreassen, C.S.; Pallesen, S.; Torsheim, T. Workaholism as a Mediator between Work-Related Stressors and Health Outcomes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andreassen, C.S.; Hetland, J.; Molde, H.; Pallesen, S. “Workaholism” and Potential Outcomes in Well-Being and Health in a Cross-Occupational Sample. Stress Health 2011, 27, e209–e214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, E.L. Insomnia. Ann. Intern. Med. 2021, 174, ITC33–ITC48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubota, K.; Shimazu, A.; Kawakami, N.; Takahashi, M.; Nakata, A.; Schaufeli, W.B. Association between Workaholism and Sleep Problems among Hospital Nurses. Ind. Health 2010, 48, 864–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caesens, G.; Stinglhamber, F.; Luypaert, G. The Impact of Work Engagement and Workaholism on Well-Being-the Role of Work-Related Social Support. Career Dev. Int. 2014, 19, 813–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubota, K.; Shimazu, A.; Kawakami, N.; Takahashi, M. Workaholism and Sleep Quality among Japanese Employees: A Prospective Cohort Study. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2014, 21, 66–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spagnoli, P.; Balducci, C.; Scafuri Kovalchuk, L.; Maiorano, F.; Buono, C. Are Engaged Workaholics Protected against Job-Related Negative Affect and Anxiety before Sleep? A Study of the Moderating Role of Gender. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scafuri Kovalchuk, L.; Buono, C.; Ingusci, E.; Maiorano, F.; De Carlo, E.; Madaro, A.; Spagnoli, P. Can Work Engagement Be a Resource for Reducing Workaholism’s Undesirable Outcomes? A Multiple Mediating Model Including Moderated Mediation Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spagnoli, P.; Balducci, C.; Fabbri, M.; Molinaro, D.; Barbato, G. Workaholism, Intensive Smartphone Use, and the Sleep-Wake Cycle: A Multiple Mediation Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doi, Y. An Epidemiologic Review on Occupational Sleep Research among Japanese Workers. Ind. Health 2005, 43, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Director-General’s Opening Remarks at the Media Briefing on COVID-19. Available online: https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020 (accessed on 2 February 2023).

- Cellini, N.; Canale, N.; Mioni, G.; Costa, S. Changes in Sleep Pattern, Sense of Time and Digital Media Use during COVID-19 Lockdown in Italy. J. Sleep Res. 2020, 29, e13074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jahrami, H.; BaHammam, A.S.; Bragazzi, N.L.; Saif, Z.; Faris, M.; Vitiello, M.V. Sleep Problems during the COVID-19 Pandemic by Population: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2021, 17, 299–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirolli, M.; Simione, L.; Martoni, M.; Fabbri, M. Accept Anxiety to Improve Sleep: The Impact of the COVID-19 Lockdown on the Relationships between Mindfulness, Distress and Sleep Quality. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 13149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haliwa, I.; Lee, J.; Wilson, J.; Shook, N.J. Mindfulness and engagement in COVID-19 oandemic behavior. Prev. Med. Rep. 2020, 20, 101246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandi, A.; Sist, L.; Martoni, M.; Colombo, L. Mental Health Outcomes in Northern Italian Workers during the COVID-19 Outbreak: The Role of Demands and Resources in Predicting Depression. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhawan, S. Online Learning: A Panacea in the Time of COVID-19 Crisis. J. Educ. Technol. Syst. 2020, 49, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thulin, E.; Vilhelmson, B.; Johansson, M. New Telework, Time Pressure, and Time Use Control in Everyday Life. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barone Gibbs, B.; Kline, C.E.; Huber, K.A.; Paley, J.L.; Perera, S. COVID-19 Shelter-at-Home and Work, Lifestyle and Well-Being in Desk Workers. Occup. Med. 2021, 71, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Suh, C.; Kim, J.E.; Park, J.O. The Impact of Long Working Hours on Psychosocial Stress Response among White-Collar Workers. Ind. Health 2017, 55, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allam, H.K.; Helmy, M.S.; El Badry, A.S.; Younis, F.E. Workaholism, Sleep Disorders, and Potential e-Learning Impacts among Menoufia University Staff during COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Public Health Res. 2021, 10, 2203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howard, F. Managing Stress or Enhancing Wellbeing? Positive Psychology’s Contributions to Clinical Supervision. Aust. Psychol. 2008, 43, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newell, J.M.; MacNeil, G.A. Professional Burnout, Vicarious Trauma, Secondary Traumatic Stress, and Compassion Fatigue: A Review of Theoretical Terms, Risk Factors, and Preventive Methods for Clinicians and Researchers. Best Pract. Ment. Health 2010, 6, 57–68. [Google Scholar]

- Sist, L.; Savadori, S.; Grandi, A.; Martoni, M.; Baiocchi, E.; Lombardo, C.; Colombo, L. Self-Care for Nurses and Midwives: Findings from a Scoping Review. Healthcare 2022, 10, 2473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, S.B.; Sweeney, A.C.; Popick, V.; Wesley, K.; Bordfeld, A.; Fingerhut, R. Self-Care Practices and Perceived Stress Levels among Psychology Graduate Students. Train. Educ. Prof. Psychol. 2012, 6, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moses, J.; Bradley, G.L.; O’Callaghan, F.V. When College Students Look after Themselves: Self-Care Practices and Well-Being. J. Stud. Aff. Res. Pract. 2016, 53, 346–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, M.; Murray, E.; Christian, M.D. Mental Health Care for Medical Staff and Affiliated Healthcare Workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Eur. Hear. J. Acute Cardiovasc. Care 2020, 9, 241–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackburn, L.M.; Thompson, K.; Frankenfield, R.; Harding, A.; Lindsey, A. The THRIVE© Program: Building Oncology Nurse Resilience Through Self-Care Strategies. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2020, 47, E25–E34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.J.; Miller, S.E. A Self-Care Framework for Social Workers: Building a Strong Foundation for Practice. Fam. Soc. 2013, 94, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.J.; Miller, S.E.; Bride, B.E. Development and Initial Validation of the Self-Care Practices Scale. Soc. Work 2019, 65, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monroe, C.; Loresto, F.; Horton-Deutsch, S.; Kleiner, C.; Eron, K.; Varney, R.; Grimm, S. The Value of Intentional Self-Care Practices: The Effects of Mindfulness on Improving Job Satisfaction, Teamwork, and Workplace Environments. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2020, 35, 189–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiske, A.; Schneider, A.; McLennan, S.; Karapetyan, S.; Buyx, A. Impact of COVID-19 on Patient Health and Self-Care Practices: A Mixed-Methods Survey with German Patients. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e051167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carney, C.E.; Edinger, J.D.; Manber, R.; Garson, C.; Segal, Z.V. Beliefs about sleep in disorders characerized by sleep and mood disturbance. J. Psychosom. Res. 2007, 62, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauk, M.; Chodkiewicz, J. The Role of General and Occupational Stress in the Relationship between Workaholism and Work-Family/Family-Work Conflicts. Int. J. Occup. Med. Environ. Health 2013, 26, 383–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Qiu, D.; Lau, M.C.M.; Lau, J.T.F. The Mediation Role of Work-Life Balance Stress and Chronic Fatigue in the Relationship between Workaholism and Depression among Chinese Male Workers in Hong Kong. J. Behav. Addict. 2020, 9, 483–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natale, V.; Fabbri, M.; Tonetti, L.; Martoni, M. Psychometric Goodness of the Mini Sleep Questionnaire. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2014, 68, 568–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Taris, T.W.; Bakker, A.B. Dr Jekyll or Mr Hyde? On the Differences between Work Engagement and Workaholism. In Research Companion to Working Time and Work Addiction; Burke, R.J., Ed.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2006; pp. 193–217. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach, 3rd ed.; The Guildford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2022; ISBN 9781462549030. [Google Scholar]

- Ariapooran, S. Sleep Problems and Depression in Iranian Nurses: The Predictive Role of Workaholism. Iran. J. Nurs. Midwifery Res. 2019, 24, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, K. Vicarious Trauma: Proposed Factors That Impact Clinicians. J. Fam. Psychother. 2010, 21, 225–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stebnicki, M.A. Empathy Fatigue: Healing the Mind, Body, and Spirit of Professional Counselors. Am. J. Psychiatr. Rehabil. 2007, 10, 317–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, K.; Campenni, C.; Muse-Burke, J. Self-Care and Well-Being in Mental Health Professionals: The Mediating Effects of Self-Awareness and Mindfulness. J. Ment. Health Couns. 2010, 32, 247–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Åkerstedt, T. Shift Work and Disturbed Sleep/Wakefulness. Occup. Med. 2003, 53, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aeschbach, D.; Matthews, J.R.; Postolache, T.T.; Jackson, M.A.; Giesen, H.A.; Wehr, T.A. Dynamics of the Human EEG during Prolonged Wakefulness: Evidence for Frequency-Specific Circadian and Homeostatic Influences. Neurosci. Lett. 1997, 239, 121–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartczak, M.; Ogiñska-Bulik, N. Workaholism and Mental Health among Polish Academic Workers. Int. J. Occup. Saf. Ergon. 2012, 18, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, J.A.; Eicken, I.M.; Castro, J.R.; Edwards, L.M.; Yokoyama, K.; Tran, A.N.T.; Haggins, K.L. Intern Self-Care: An Exploratory Study into Strategy Use and Effectiveness. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 2005, 36, 674–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common Method Biases in Behavioral Research: A Critical Review of the Literature and Recommended Remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho, S.; Barrios, A. Teleworking and Technostress: Early Consequences of a COVID-19 Lockdown. Cogn. Technol. Work 2022, 24, 441–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandi, A.; Zito, M.; Sist, L.; Martoni, M.; Russo, V.; Colombo, L. Wellbeing in Workers during COVID-19 Pandemic: The Mediating Role of Self-Compassion in the Relationship between Personal Resources and Exhaustion. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (M = 42.58; DS = 10.68) | ||

| Gender | ||

| Female | 288 | 71.1 |

| Male | 117 | 28.9 |

| Relationship Status | ||

| Single | 139 | 34.3 |

| Married/cohabiting | 238 | 58.8 |

| Separated/divorced | 24 | 5.9 |

| Widow/widower | 4 | 1.0 |

| Education | ||

| Lower secondary school diploma | 14 | 3.5 |

| Vocational school diploma | 13 | 3.2 |

| High school diploma | 126 | 31.1 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 29 | 7.2 |

| Master’s degree | 147 | 36.3 |

| Post-graduate training | 76 | 18.8 |

| Professional Sectors | ||

| Agriculture and Handicraft | 9 | 2.2 |

| Business consulting | 32 | 7.9 |

| Culture, Sport, and Tourism | 29 | 7.2 |

| Education and Research | 78 | 19.3 |

| Healthcare services | 67 | 16.5 |

| Industry | 26 | 6.4 |

| Mass media and Telecommunications | 16 | 4.0 |

| Public services and Administration | 36 | 8.9 |

| Social services | 18 | 4.4 |

| Trade/Commerce | 35 | 8.6 |

| Other | 55 | 13.6 |

| Missing | 4 | 1.0 |

| Professional Categories | ||

| Blue collar | 15 | 3.7 |

| Educator and Social Worker | 10 | 2.5 |

| Healthcare professional | 42 | 10.4 |

| Manager, Director | 11 | 2.7 |

| Scholar, Researcher, and Teacher | 78 | 19.3 |

| Self-employed professional | 56 | 13.8 |

| White collar | 168 | 41.5 |

| Other | 21 | 5.2 |

| Missing | 4 | 1.0 |

| Group with Sleep Problems | Group without Sleep Problems | Group Comparison t-Test | Group with Wake Problems | Group without Wake Problems | Group Comparison t-Test | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCPS | 17.34 (5.87) | 20.99 (6.47) | t(403) = 5.86, p < 0.0001 | 17.69 (6.06) | 20.41 (6.50) | t(403) = 4.18, p < 0.0001 |

| WE | 14.30 (3.69) | 13.44 (3.41) | t(403) = −2.42, p < 0.05 | 14.64 (3.60) | 13.32 (3.44) | t(403) = −3.69, p < 0.0001 |

| WC | 13.11 (3.25) | 12.12 (2.83) | t(403) = −3.27, p < 0.001 | 13.35 (3.22) | 12.08 (2.86) | t(403) = −4.16, p < 0.0001 |

| Sleep Factor Score | Wake Factor Score | SCPS Score | WE Score | WC Score | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sleep factor score | 1 | +0.66 ** | −0.32 ** | +0.19 ** | +0.23 ** |

| Wake factor score | - | 1 | −0.26 ** | +0.26 ** | +0.25 ** |

| SCPS score | - | - | 1 | −0.11 * | −0.10 ° |

| WE score | - | - | - | 1 | +0.51 ** |

| WC score | - | - | - | - | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Martoni, M.; Fabbri, M.; Grandi, A.; Sist, L.; Colombo, L. Self-Care Practices as a Mediator between Workaholism and Sleep–Wake Problems during COVID-19. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12603. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151612603

Martoni M, Fabbri M, Grandi A, Sist L, Colombo L. Self-Care Practices as a Mediator between Workaholism and Sleep–Wake Problems during COVID-19. Sustainability. 2023; 15(16):12603. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151612603

Chicago/Turabian StyleMartoni, Monica, Marco Fabbri, Annalisa Grandi, Luisa Sist, and Lara Colombo. 2023. "Self-Care Practices as a Mediator between Workaholism and Sleep–Wake Problems during COVID-19" Sustainability 15, no. 16: 12603. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151612603

APA StyleMartoni, M., Fabbri, M., Grandi, A., Sist, L., & Colombo, L. (2023). Self-Care Practices as a Mediator between Workaholism and Sleep–Wake Problems during COVID-19. Sustainability, 15(16), 12603. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151612603