‘Simply Make a Change’—Individual Commitment as a Stepping Stone for Sustainable Behaviors

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Commitment as a Tool for Behavior Change

1.2. Moderating Factors

1.3. Rationale of the Study and Research Questions

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Overview

2.2. Selection of Behaviors

2.3. Project Website

2.4. Registration, Ethical Considerations and Questionnaires

2.5. Interviews

2.6. Participants and Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Choice of Behavior, Frequency of Implementation and Perceived Difficulty (Q1)

3.2. Experiences with the Commitment and the Eight Behaviors (Q2)

“It is not that difficult to improve your behavior towards the environment. Often, there is a plastic-free alternative or at least one with less plastic. I could not find some things plastic-free, e.g., toilet paper, cottage cheese, curd cheese, paper tissues.” [...] One month later: “It is easy for me if there is a plastic-free alternative or if I have to make slight compromises. In this case, I buy the plastic-free product. It is difficult for me if I cannot get certain products plastic-free or have not yet found them. [...] I cannot do without some of these products; I do not want to do without some” (woman, 63 years old).

“I did not really perceive it as a sacrifice, since I treated myself to a lot of things that I do not usually buy (e.g., various vegan spreads, special types of tofu). I also made vegan spreads myself—it was not difficult, because there are now many vegan products available.” One month later: “In some situations you are excluded and cannot eat when the offer is not vegan” (man, 30 years old).

“I liked the fact that I felt bound by the commitment and that I was less able to shirk the “work”. Basically, I am reluctant to clean up other people’s rubbish as I myself do not leave anything outside a dustbin or take everything home again. I belong to the “good guys” and have no behavior to change. That is why I believe that my civic engagement makes it too easy for the perpetrators. Personally, it has been a huge problem for me to collect garbage in front of everyone.” One month later: “Although the discussion among colleagues was quite controversial, I am surprised that I believe I can make a difference (role model function) and that I feel good about it (better than complaining about the dirt)” (woman, 61 years old).

“I finally did things I had actually wanted to do for a long time: bought and installed new LED lamps; replaced the old so-called energy-saving lamps, which had annoyed me long enough because they took so long to get bright. While thinking about the possibilities, I realized that I automatically switch on the light in the cellar even in broad daylight. [...] I have noticed how deep-rooted many things are and how much effort is needed to stop bad behavior and habits.” One month later: “Actually, I would not find it difficult if it was not for the convenience. [...] Environmentally-friendly behavior is actually a matter of mind and awareness and of overcoming comfortable or habitual behavior. If you are aware of this, it helps you to correct some things and you are rewarded with small feelings of success” (woman, 29 years old).

“I really enjoyed taking a closer look at the products I buy. It is a great idea to rethink your habits and see how you can change something in your everyday life. I expected more information from the app. I thought that there might be some information regarding different labels.” One month later: “It is easy for me because I hardly buy products that contain environmentally harmful substances. I can check those that are questionable which applies especially to cosmetic products or detergents” (woman, 24 years old).

“You buy more consciously and purposefully and not mass products. Many organic products are packaged in plastic, which in my opinion is a big contradiction.” One month later and continuing the behavior: “Because I think it is important not only to talk about sustainability, but to live it” (man, 35 years old).

“I paid more attention to my daily planning and time management. I like the sporty aspect of moving around by bike. I became more confident in dealing with timetables and public transport. Negative were the extra time to carry out the commitment and the delays of public transport.” One month later: “Since I have always liked to ride a bike, I have done it now more often (instead of using the car). I am also now more familiar with public transport and feel confident to get around without a car. The environmentally-friendly behavior gives me the good feeling of doing something for climate protection and health” (woman, 62 years old).

“I made soap myself. It has to mature for six months. I also made dishwashing liquid—that works great. I have also prepared the vinegar cleaner. It has to soak for at least two weeks. [...] One week is too short. It takes at least a year to make your own cosmetics—you have to find out where to find the materials, the recipes” [...]. One month later: “You have to plan in advance to have detergents ready when you need them” (woman, 34 years old).

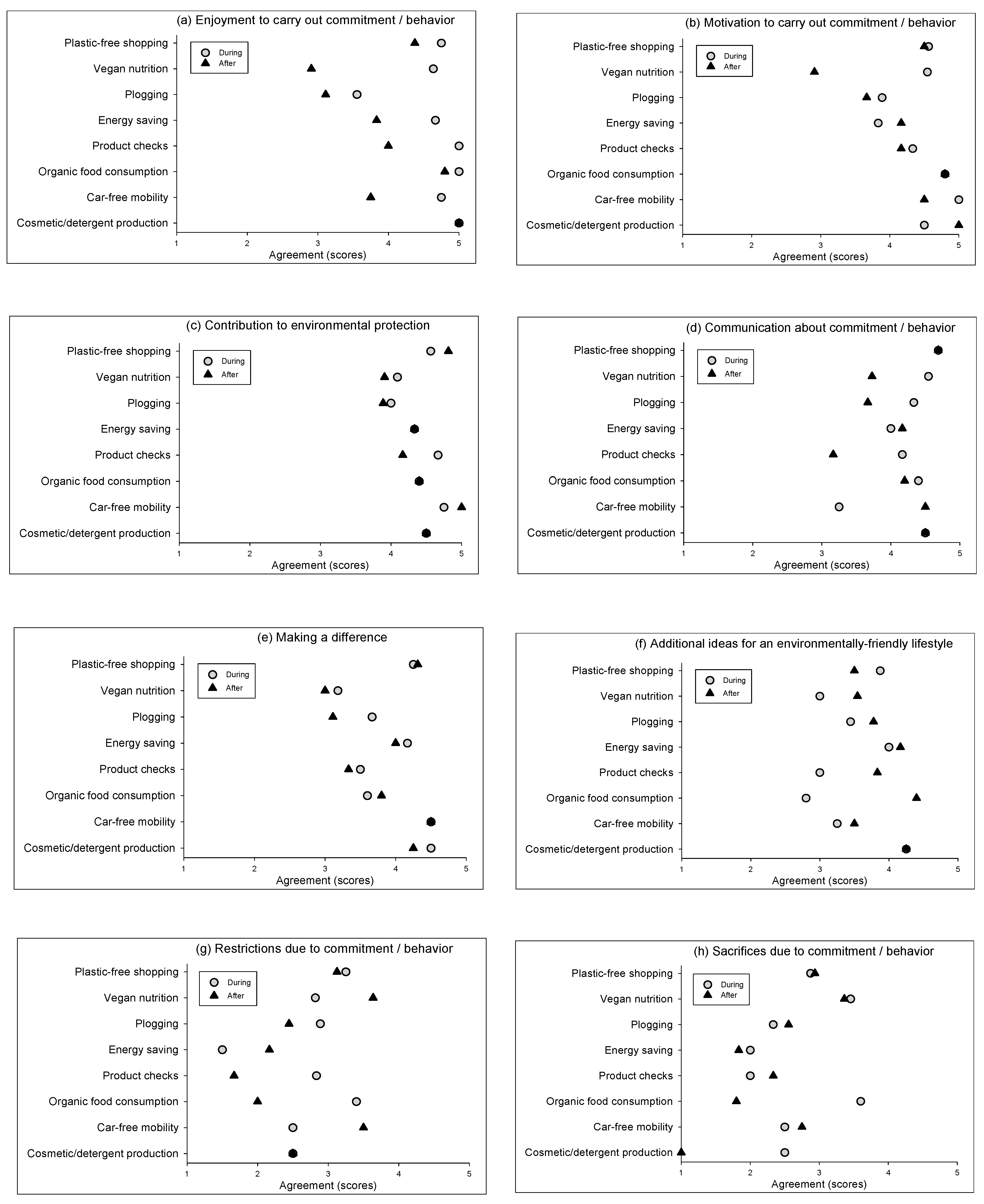

3.3. Evaluation of Commitment and Behavior (Q3)

3.4. Impressions Two Months Later (Q4)

4. Discussion

Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Behavior | Mean Score ± 1 SE | Behavior | Mean Score ± 1 SE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Using plastic bags more than once | 1.2 ± 0.05 | Not driving to work by car | 2.1 ± 0.12 |

| Using own shopping bag | 1.2 ± 0.05 | Driving < 130 km/h on highways | 2.3 ± 0.11 |

| Showering instead of bathing | 1.3 ± 0.06 | Avoiding a tumble dryer | 2.3 ± 0.11 |

| Using an organic waste bin | 1.3 ± 0.06 | Shopping without a car | 2.3 ± 0.11 |

| Recycling glass | 1.3 ± 0.06 | Avoiding standby mode | 2.3 ± 0.11 |

| Turning off lights when leaving a room | 1.4 ± 0.07 | Purchasing sustainable electricity | 2.4 ± 0.09 |

| Using clothes for as long as possible | 1.5 ± 0.07 | Buying fair trade food | 2.4 ± 0.09 |

| Using mobile phones for > 2.5 years | 1.5 ± 0.07 | Reducing meat consumption | 2.4 ± 0.11 |

| Recycling paper waste | 1.5 ± 0.08 | Public transport for distances < 30 km | 2.4 ± 0.12 |

| Washing laundry without pre-washing | 1.6 ± 0.08 | No overheating | 2.4 ± 0.10 |

| Refusing plastic bags when offered | 1.6 ± 0.08 | Turning mobile phone off at night | 2.5 ± 0.12 |

| Turning down the heating at night | 1.6 ± 0.08 | Using an all-purpose cleaning agent | 2.5 ± 0.10 |

| Filling up the washing machine | 1.6 ± 0.08 | Plastic-reduced shopping | 2.6 ± 0.10 |

| Using energy-efficient illuminants | 1.6 ± 0.07 | Using cosmetics without microplastic | 2.7 ± 0.11 |

| Avoiding food waste | 1.7 ± 0.08 | No travelling by airplane | 2.7 ± 0.11 |

| Disposing batteries at a collection point | 1.8 ± 0.09 | Boycotting unecological companies | 2.7 ± 0.10 |

| Using recycable bottles | 1.9 ± 0.09 | Using apps for harmful ingredient checks | 2.7 ± 0.11 |

| Using energy efficient technical devices | 1.9 ± 0.09 | Using biological detergents | 2.8 ± 0.11 |

| Using accus instead of batteries | 2.0 ± 0.09 | Second-hand shopping | 3.0 ± 0.11 |

| Using recycled toilet paper | 2.0 ± 0.10 | Buying milk in glass bottles | 3.0 ± 0.11 |

| Turning down the heating when absent | 2.1 ± 0.10 | Buying organic/fair clothing | 4.2 ± 0.10 |

| Shopping seasonal and regional products | 2.1 ± 0.09 | Using car-sharing | 4.2 ± 0.11 |

| Shopping organic groceries | 2.1 ± 0.09 | Being mobile without a car | 4.2 ± 0.12 |

| Flying only once a year | 2.1 ± 0.10 | Installing a solar system | 4.3 ± 0.11 |

| Using train or bus for long distances | 2.1 ± 0.11 | Eating a vegan diet | 4.9 ± 0.10 |

References

- Bradshaw, C.J.A.; Ehrlich, P.R.; Beattie, A.; Ceballos, G.; Crist, E.; Diamond, J.; Dirzo, R.; Ehrlich, A.H.; Harte, J.; Harte, M.E.; et al. Underestimating the Challenges of Avoiding a Ghastly Future. Front. Conserv. Sci. 2021, 1, e615419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skogen, K.; Helland, H.; Kaltenborn, B. Concern about climate change, biodiversity loss, habitat degradation and landscape change: Embedded in different packages of environmental concern? J. Nat. Conserv. 2018, 44, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodur, H.O.; Duval, K.M.; Grohmann, B. Will You Purchase Environmentally Friendly Products? Using Prediction Requests to Increase Choice of Sustainable Products. J. Bus. Ethic 2014, 129, 59–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshood, T.D.; Nawanir, G.; Mahmud, F. Sustainability of biodegradable plastics: A review on social, economic, and environmental factors. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2021, 42, 892–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- BMU (Bundesministerium für Umwelt, Naturschutz, Nukleare Sicherheit und Verbraucherschutz). Umweltbewusstsein in Deutschland 2020. Ergebnisse Einer Repräsentativen Bevölkerungsumfrage. Umweltbundesamt (UBA): Dessau-Roßlau, Germany. 2022. Available online: https://www.umweltbundesamt.de/sites/default/files/medien/479/publikationen/ubs_2020_0.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2023).

- Farjam, M.; Nikolaychuk, O.; Bravo, G. Experimental evidence of an environmental attitude-behavior gap in high-cost situations. Ecol. Econ. 2019, 166, 106434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiederhold, M.; Martinez, L.F. Ethical consumer behaviour in Germany: The attitude-behaviour gap in the green apparel industry. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2018, 42, 419–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrington, M.J.; Neville, B.A.; Whitwell, G.J. Lost in translation: Exploring the ethical consumer intention–behavior gap. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 2759–2767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollmuss, A.; Agyeman, J. Mind the Gap: Why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behavior? Environ. Educ. Res. 2002, 8, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenzie-Mohr, D. Fostering Sustainable Behavior: An Introduction to Community-Based Social Marketing, 3rd ed.; New Society Publishers: Gabriola Island, BC, Canada, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Diekmann, A.; Preisendörfer, P. Green and Greenback: The behavioral effects of environmental attitudes in low-cost and high-cost situations. Ration. Soc. 2003, 15, 441–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steg, L.; Vlek, C. Encouraging pro-environmental behaviour: An integrative review and research agenda. J. Environ. Psychol. 2009, 29, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyss, A.M.; Knoch, D.; Berger, S. When and how pro-environmental attitudes turn into behavior: The role of costs, benefits, and self-control. J. Environ. Psychol. 2022, 79, e101748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.V.; Nguyen, C.H.; Hoang, T.T.B. Green consumption: Closing the intention-behavior gap. Sustain. Dev. 2018, 27, 118–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, W.; Quinn, J.M.; Kashy, D.A. Habits in everyday life: Thought, emotion, and action. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 83, 1281–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisk, E.; Larson, K.L. Educating for sustainability: Competencies & practices for transformative action. J. Sustain. Educ. 2011, 2, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Kiesler, C.A.; Sakumura, J. A test of a model for commitment. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1966, 3, 349–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindemann-Matthies, P.; Hoyer, E.; Remmele, M. Collective Public Commitment: Young People on the Path to a More Sustainable Lifestyle. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lokhorst, A.M.; Werner, C.; Staats, H.; van Dijk, E.; Gale, J.L. Commitment and Behavior Change: A meta-analysis and critical review of commitment-making strategies in environ-mental research. Environ. Behav. 2011, 45, 3–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staats, H.; Harland, P.; Wilke, H.A.M. Effecting durable change: A team approach to improve environmental behavior in the household. EAB 2004, 36, 341–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Werff, E.; Taufik, D.; Venhoeven, L. Pull the plug: How private commitment strategies can strengthen personal norms and promote energy-saving in the Netherlands. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2019, 54, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthies, E.; Klockner, C.A.; Preissner, C.L. Applying a Modified Moral Decision Making Model to Change Habitual Car Use: How Can Commitment be Effective? Appl. Psychol. 2006, 55, 91–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allcott, H. Social norms and energy conservation. J. Public Econ. 2011, 95, 1082–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckmann, M.; Hielscher, S.; Pies, I. Commitment Strategies for Sustainability: How Business Firms Can Transform Trade-Offs into Win-Win Outcomes. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2012, 23, 18–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bator, R.J.; Cialdini, R.B. The Application of Persuasion Theory to the Development Of Effective Proenvironmental Public Service Announcements. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 527–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gneezy, U.; Meier, S.; Rey-Biel, P. When and Why Incentives (Don’t) Work to Modify Behavior. J. Econ. Perspect. 2011, 25, 191–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royer, H.; Stehr, M.; Sydnor, J. Incentives, Commitments, and Habit Formation in Exercise: Evidence from a Field Experiment with Workers at a Fortune-500 Company. Am. Econ. J. Appl. Econ. 2015, 7, 51–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenbroele, J.; Vermeir, I.; Geuens, M.; Slabbinck, H.; Van Kerckhove, A. Nudging to get our food choices on a sustainable track. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2019, 79, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wensing, J.; Caputo, V.; Carraresi, L.; Bröring, S. The effects of green nudges on consumer valuation of bio-based plastic packaging. Ecol. Econ. 2020, 178, 106783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.; Picard, J. Thinking through Norms Can Make Them more Effective: Experimental evidence on reflective climate policies in the UK. J. Behav. Exp. Econ. 2023, 102024. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4155188 (accessed on 20 June 2023).

- Lülfs, R.; Hahn, R. Sustainable Behavior in the Business Sphere: A comprehensive overview of the explanatory power of psychological models. Organ. Environ. 2014, 27, 43–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouro, C.; Duarte, A.P. Organisational Climate and Pro-environmental Behaviours at Work: The Mediating Role of Personal Norms. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, e635739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riess, W.; Martin, M.; Mischo, C.; Kotthoff, H.-G.; Waltner, E.-M. How Can Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) Be Effectively Implemented in Teaching and Learning? An Analysis of Educational Science Recommendations of Methods and Procedures to Promote ESD Goals. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Too, L.; Bajracharya, B. Sustainable campus: Engaging the community in sustainability. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2015, 16, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paige, K. Educating for sustainability: Environmental pledges as part of tertiary pedagogical practice in science teacher education. Asia-Pacific J. Teach. Educ. 2017, 45, 285–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reese, G.; Junge, E.A. Keep on Rockin’ in a (Plastic-)Free World: Collective Efficacy and Pro-Environmental Intentions as a Function of Task Difficulty. Sustainability 2017, 9, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diekmann, A.; Preisendörfer, P. Environmental Behavior: Discrepancies between aspirations and reality. Ration. Soc. 1998, 10, 79–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frick, J.; Scheuthle, H. Trendbewusste Ökos und naturverbundene Autofahrer. ETH-Bulletin 2001, 281, 40–43. [Google Scholar]

- Ouellette, J.A.; Wood, W. Habit and intention in everyday life: The multiple processes by which past behavior predicts future behavior. Psychol. Bull. 1998, 124, 54–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verplanken, B.; Wood, W. Interventions to Break and Create Consumer Habits. J. Public Policy Mark. 2006, 25, 90–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, G.; Sovacool, B.; Aall, C.; Nilsson, M.; Barbier, C.; Herrmann, A.; Bruyère, S.; Andersson, C.; Skold, B.; Nadaud, F.; et al. It starts at home? Climate policies targeting household consumption and behavioral decisions are key to low-carbon futures. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2019, 52, 144–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, D.; Barrett, J.; Wiedenhofer, D.; Macura, B.; Callaghan, M.W.; Creutzig, F. Quantifying the potential for climate change mitigation of consumption options. Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 093001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, J.; Castro, S.L.; Souza, A.S. Psychological barriers moderate the attitude-behavior gap for climate change. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0287404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lokhorst, A.M.; Staats, H.; van Iterson, J. Energy Saving in Office Buildings: Are Feedback and Commitment-Making Useful Instruments to Trigger Change? Hum. Ecol. 2015, 43, 759–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, M.; Yang, C. Research on Consumer Identity in Using Sustainable Mobility as a Service System in a Commuting Scenario. Systems 2022, 10, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, M.; Busch, C.; Rödiger, M.; Hamm, U. Motives of consumers following a vegan diet and their attitudes towards animal agriculture. Appetite 2016, 105, 643–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, W.; Choi, Y. Examining Plogging in South Korea as a New Social Movement: From the Perspective of Claus Offe’s New Social Movement Theory. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Resnik, A.J.; Cialdini, R.B. Influence: Science and Practice; Allyn and Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, F.G.; Keller, C. Disclosing situational constraints to ecological behavior: A confirmatory application of the mixed Rasch model. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 2001, 17, 212–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, S.; Myers, G. Conservation psychology. In Understanding and Promoting Human Care for Nature; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Mayring, P. Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse, 12th ed.; Beltz: Weinheim, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, H.V.; Le, M.T.T.; Pham, C.H.; Cox, S.S. Happiness and pro-environmental consumption behaviors. J. Econ. Dev. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steg, L.; Bolderdijk, J.W.; Keizer, K.; Perlaviciute, G. An Integrated Framework for Encouraging Pro-environmental Behaviour: The role of values, situational factors and goals. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 38, 104–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Haan, G. The development of ESD-related competencies in supportive institutional frameworks. Int. Rev. Educ. 2010, 56, 315–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dannenberg, S.; Grapentin, T. Education for sustainable development-learning for transformation: The example of Germany. J. Futures Stud. 2016, 20, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerschke-Risch, P. Vegan diet: Motives, approach and duration. Initial results of a quantitative sociological study. Ernaehr.-Umsch. 2015, 62, 98–103. [Google Scholar]

- Cooney, N. Veganomics. In The Surprising Science on Vegetarians, from the Breakfast Table to the Bed-Room; Lantern Books: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Michel, F.; Hartmann, C.; Siegrist, M. Consumers’ associations, perceptions and acceptance of meat and plant-based meat alternatives. Food Qual. Prefer. 2020, 87, 104063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidbreder, L.M.; Steinhorst, J.; Schmitt, M. Plastic-Free July: An Experimental Study of Limiting and Promoting Factors in Encouraging a Reduction of Single-Use Plastic Consumption. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penz, E.; Hartl, B.; Hofmann, E. Explaining consumer choice of low carbon footprint goods using the behavioral spillover effect in German-speaking countries. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 214, 429–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleim, M.R.; Smith, J.S.; Andrews, D.; Cronin, J.J., Jr. Against the Green: A Multi-method Examination of the Barriers to Green Consumption. J. Retail. 2013, 89, 44–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazaroiu, G.; Andronie, M.; Uţă, C.; Hurloiu, I. Trust Management in Organic Agriculture: Sustainable Consumption Behavior, Environmentally Conscious Purchase Intention, and Healthy Food Choices. Front. Public Health 2019, 7, e340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, J.; Paul, J. Consumer behavior and purchase intention for organic food: A review and research agenda. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2017, 38, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosglik, R. Citizen-consumer revisited: The cultural meanings of organic food consumption in Israel. J. Consum. Cult. 2017, 17, 732–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taufik, D.; Bolderdijk, J.W.; Steg, L. Acting green elicits a literal warm glow. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2015, 5, 37–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Linden, S. Warm glow is associated with low- but not high-cost sustainable behaviour. Nat. Sustain. 2018, 1, 28–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lally, P.; van Jaarsveld, C.H.; Potts, H.W.; Wardle, J. How are habits formed: Modelling habit formation in the real world. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 40, 998–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloodhart, B.; Swim, J.K. Sustainability and Consumption: What’s Gender Got to Do with It? J. Soc. Issues 2020, 76, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brough, A.R.; Wilkie, J.E.B.; Ma, J.; Isaac, M.S.; Gal, D. Is Eco-Friendly Unmanly? The Green-Feminine Stereotype and Its Effect on Sustainable Consumption. J. Consum. Res. 2016, 43, 567–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, L.M.; Hatch, A.; Johnson, A. Cross-National Gender Variation in Environmental Behaviors. Soc. Sci. Q. 2004, 85, 677–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCrory, G.; Schäpke, N.; Holmén, J.; Holmberg, J. Sustainability-oriented labs in real-world contexts: An exploratory review. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 277, e123202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevens, F.; Frantzeskaki, N.; Gorissen, L.; Loorbach, D. Urban Transition Labs: Co-creating transformative action for sustainable cities. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 50, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Behavior | Mean Days of Execution | Perceived Difficulty (Mean Scores ± 1 SE) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Commitment Week (7 Days) | Afterwards (30 Days) | Overall (# Days) | During Commitment | After Commitment | Overall Mean | |

| Plastic-free shopping (27/16) | 5.4 | 12.5 | 18.2 | 3.4 ± 0.29 | 3.4 ± 0.20 | 3.4 ± 0.23 |

| Vegan nutrition (21/11) | 6.6 | 5.4 | 12.1 | 2.6 ± 0.28 | 3.7 ± 0.20 | 3.2 ± 0.21 |

| Plogging (15/9) | 4.6 | 5.7 | 10.7 | 3.1 ± 0.46 | 3.2 ± 0.32 | 3.2 ± 0.22 |

| Energy saving (10/6) | 5.3 | 16.0 | 21.8 | 2.8 ± 0.17 | 2.8 ± 0.31 | 2.8 ± 0.17 |

| Product check with Apps (9/6) | 4.2 | 3.0 | 7.2 | 2.2 ± 0.31 | 2.8 ± 0.48 | 2.5 ± 0.29 |

| Organic food consumption (8/5) | 5.6 | 8.8 | 14.4 | 3.2 ± 0.37 | 2.8 ± 0.20 | 3.0 ± 0.27 |

| Car-free mobility (6/4) | 6.8 | 14.3 | 21.0 | 2.5 ± 0.50 | 2.5 ± 0.29 | 2.5 ± 0.35 |

| Cosmetic/detergent production (5/4) | 4.3 | 15.0 | 18.3 | 2.3 ± 0.25 | 3.0 ± 0.41 | 2.6 ± 0.31 |

| Categories/Subcategories | Examples |

|---|---|

| Personal Experiences (n = 65) | |

| Sense of achievement (54) | Saving electricity is actually very easy. The project week helped me to put it into practice, and there is no good reason to stop it now (w, 64, energy saving). |

| Exchange with others and multiplication effect (13) | Many discussions about my topic have emerged and stimulated me and others to make lasting changes (w, 40, organic shopping). I was able to motivate neighbors and friends to participate in the collection of garbage (w, 37, plogging). |

| Motivation and challenges (13) | I am motivated to make lasting changes (w, 22, organic shopping). I found it challenging that I always had to take the bike (m, 39, car-free mobility). |

| Enjoyment and satisfaction (12) | It was fun to deal more consciously with my diet (w, 26, vegan nutrition). The more days I collected, the cleaner my walk became—and still is—and I am happy (w, 56, plogging). |

| Capacity building (n = 61) | |

| Awareness and mindfulness (39) | Participation has increased my awareness. Not just for energy saving, but generally for sustainable behavior (w, 21, energy saving). Attention has been drawn to small things that are harmful to the environment and which you would otherwise not notice (m, 24, car-free mobility). |

| Action competence (28) | I will continue to reduce my plastic consumption (w, 23, plastic-free shopping). Organic milk was always sold out and I finally complained about it. I had a nice conversation with the shop manager that will change his ordering behavior permanently (w, 40, organic shopping). |

| Reflection (21) | The commitment has shown me that it is often possible to use a bike. Most of the time, habit is the reason to use the car (w, 31, car-free mobility). I might only have used energy a bit less, but if we would all do it consistently, we could certainly shut down some power plants (w, 64, energy saving). |

| Obtaining information (16) | Researching and collecting information was stimulating. I wrote down which products are wrapped in plastic and which I actually do not need (w, 30, plastic-free shopping). |

| Planning and self-control (6) | I need to pay attention to little things: always have my own spoon and a box with me when ordering ice cream or taking leftovers from a restaurant (w, 22, plastic-free shopping). |

| Feeling of responsibility (4) | I got a feeling of responsibility for my environment through these small actions (w, 27, plogging). |

| Methodology (n = 38) | |

| General insights (24) | I think we should often spend a week like this to remind ourselves of certain values, to constantly increase awareness and to try out new things. I am sure that every time something will stick (w, 26, organic shopping). |

| Initiation of behavior (13) | I have finally done things that I have wanted to do for a long time (w, 76, energy saving). |

| Transfer to other topics (8) | I got ideas for other possible commitments, several of which I find very interesting (w, 29, energy saving). |

| Sense of duty (6) | The commitment is voluntary, but you have to report on it after a week. This gets you going (m, 26, plogging). |

| Categories/Subcategories | Examples |

|---|---|

| Obstacles (n = 66) | |

| General difficulties (40) | I quickly gave up on my walk next to the train tracks, because of the huge amount of rubbish lying around; some things were just too nasty to pick up (w, 27, plogging). |

| Old habits (21) | In many situations, one tends to forget the voluntary commitment out of habit. The tasks really need to be made consciously, which is quite an effort (man, 32, energy saving). |

| Restrictions and sacrifices (18) | We could not buy things we actually needed as they were not plastic-free (m, 63, plastic-free shopping). In some situations you cannot eat when no vegan food is on offer (m, 30, vegan nutrition). |

| Time constraints (10) | I detested the extra time it took me, and the delays and unpunctuality of public transport (w, 67, car-free mobility). |

| Lack of social acceptance (9) | I started to avoid crowds and stopped when I felt watched (w, 52, plogging). |

| Revelation (8) | I was aware of how ubiquitous plastic is. But during this week and in preparation for it did I realize how pervasive it is. I had the impression that there is almost nothing that is not wrapped up in plastic (w, 63, plastic-free shopping). |

| Financial constraints (8) | Since we did not shop at discounters, costs were greatly increased this week (w, 32, organic shopping). |

| Methodology (27) | |

| Project duration (17) | The commitment should be for a little longer so that the new behavior can become a routine (w, 31, product checks). |

| Relevance and impact (5) | I question the relevance and impact of my doings (m, 26, plogging). I have not used a hair-dryer. I might not keep up such small activities as they have so little impact (w, 29, energy saving). |

| More information (5) | Links to interesting websites would have been stimulating and helpful (w, 22, plastic-free shopping). |

| Categories/Subcategories | Example Statements |

|---|---|

| Barriers (46) | |

| Sacrifices, old habits and routine (37) | It is very difficult for me to do without cheese and right now, during barbecue season, meat simply tastes too delicious. It is certainly a habit (w, 30, vegan nutrition). You quickly return to routine; a week is too short for changing a behavior (w, 27, plastic-free shopping) |

| Situational, time and financial constraints (19) | I plan to go back to nature armed with bags, but unfortunately, I have not found the time in the past four weeks. In my opinion, jogging is less of an option, because then it is actually only collecting instead of jogging. There is simply too much garbage everywhere—very frightening (w, 37, plogging). Living in the country, you have to plan a lot because you have to go into town—and the items are more expensive than the ones you can buy in the local supermarket—and not necessarily better (m, 63, plastic free shopping). |

| Successes (39) | |

| Increased consciousness and changes of habits (39) | Environmentally-friendly behavior is actually a matter of mind and awareness—and often the overcoming of comfortable or accustomed behavior. If you realize that, it will help to correct things—and you will be rewarded with small success stories (w, 77, energy saving) |

| Statements (Questionnaire 1/Questionnaire 2) | Mean Score ± 1 SE | |

|---|---|---|

| During | After | |

| I was happy to carry out the commitment//I still enjoy carrying out my behavior | 4.6 ± 0.14 | 3.9 ± 0.14 |

| I was motivated to successfully implement the commitment/I am motivated to carry on with my behavior | 4.4 ± 0.10 | 4.1 ± 0.13 |

| I see the commitment/my behavior as an important contribution to environmental protection | 4.4 ± 0.10 | 4.4 ± 0.10 |

| I talked to other people about my commitment/during the last weeks I have talked to other people about my behavior | 4.4 ± 0.13 | 4.1 ± 0.14 |

| The commitment made me feel that I could make a difference through my environmentally-friendly actions | 3.9 ± 0.14 | 3.7 ± 0.15 |

| During the commitment week I came up with more ideas …/… the last weeks I have realized ideas for an environmentally-friendly lifestyle | 3.5 ± 0.14 | 3.8 ± 0.15 |

| I felt restricted in everyday life by my commitment/I feel restricted in everyday life by my behavior | 2.8 ± 0.15 | 2.8 ± 0.15 |

| I had to give up things due to my commitment/I have to give up things due to my behavior | 2.7 ± 0.17 | 2.6 ± 0.17 |

| Categories | Examples |

|---|---|

| Increased awareness and action competence (18) | Yes, I think mindfulness already plays a role. I think twice—do I really need it now, is it just convenience or what motivation do I have to use the car (m, 39, car-free mobility). It is important that we as customers communicate to shops and manufacturers that we want alternatives, that we want plastic-free products. I cannot understand why recycled toilet paper has to be wrapped up in plastic. I wrote that to a health-food store. If the manufacturers adjust to this, a lot can be achieved, much more than trying to change something as an individual (w, 62, plastic-free shopping). |

| Sensitization for sustainable actions in general (3) | It is not only saving electricity, but when you become aware of one thing, you also think about completely different things. And little by little there are other habits. […] The coolest thing I really found was that the project spreads like a spiral into all other areas of life (w, 23, energy saving). You also pay attention to more difficult things and behaviors, and you already create a transfer (w, 41, organic shopping). |

| Erosion of behavior (17) | It does not work 100 percent but I do it as often as possible (m, 28, plastic-free shopping). As long as I could tell someone about the commitment week—this may sound silly now—I took it seriously. I still carry on with my behavior because I know that it is a good thing. But I think it will expire. That someday I will not do it anymore (m, 26, plogging). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lindemann-Matthies, P.; Werdermann, J.; Remmele, M. ‘Simply Make a Change’—Individual Commitment as a Stepping Stone for Sustainable Behaviors. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12163. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151612163

Lindemann-Matthies P, Werdermann J, Remmele M. ‘Simply Make a Change’—Individual Commitment as a Stepping Stone for Sustainable Behaviors. Sustainability. 2023; 15(16):12163. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151612163

Chicago/Turabian StyleLindemann-Matthies, Petra, Julia Werdermann, and Martin Remmele. 2023. "‘Simply Make a Change’—Individual Commitment as a Stepping Stone for Sustainable Behaviors" Sustainability 15, no. 16: 12163. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151612163

APA StyleLindemann-Matthies, P., Werdermann, J., & Remmele, M. (2023). ‘Simply Make a Change’—Individual Commitment as a Stepping Stone for Sustainable Behaviors. Sustainability, 15(16), 12163. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151612163