Necessity to Assess the Sustainability of Sensitive Ecosystems: A Comprehensive Review of Tourism Pressures and the Travel Cost Method

Abstract

1. Introduction

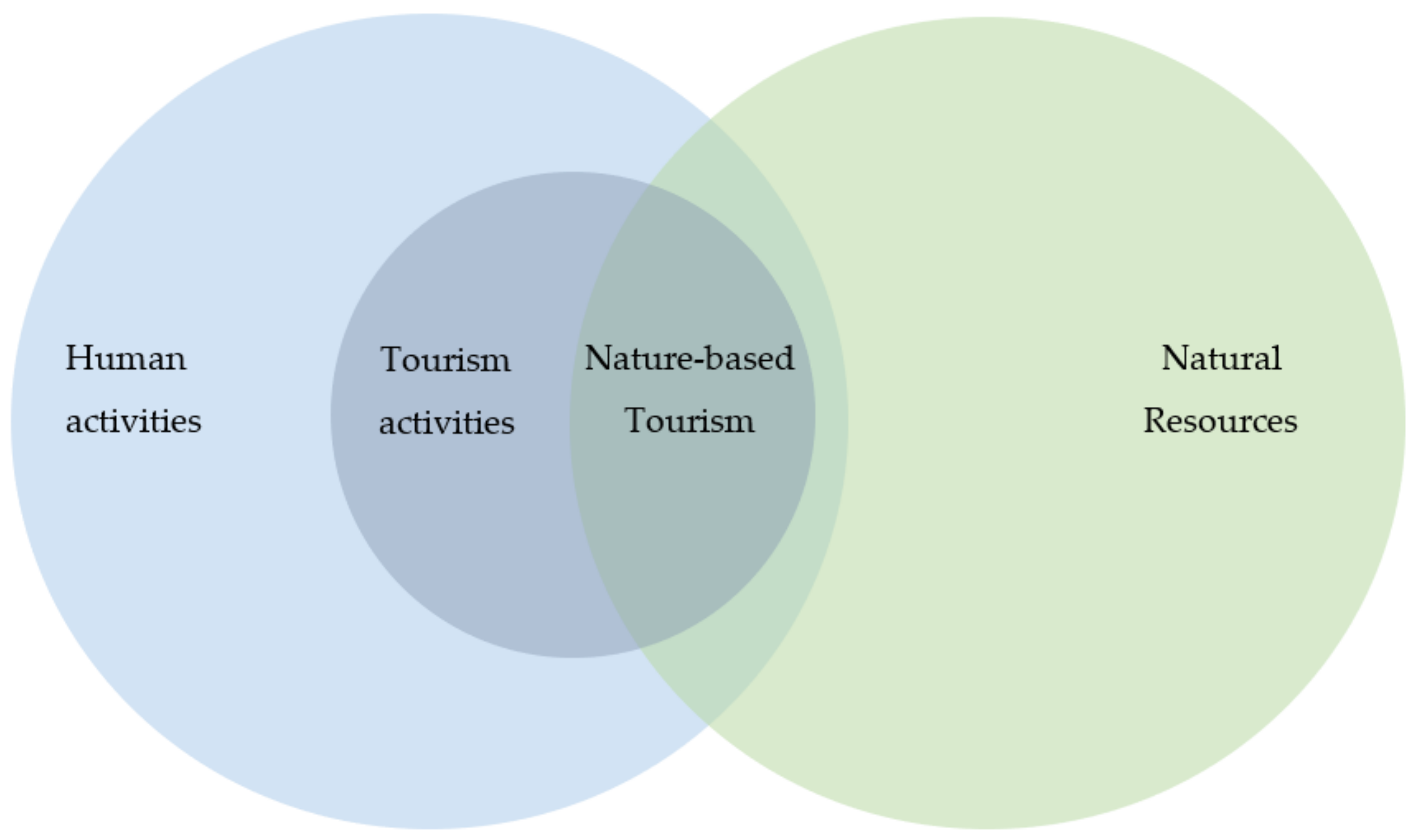

2. Sustainable Tourism and Sensitive Ecosystems

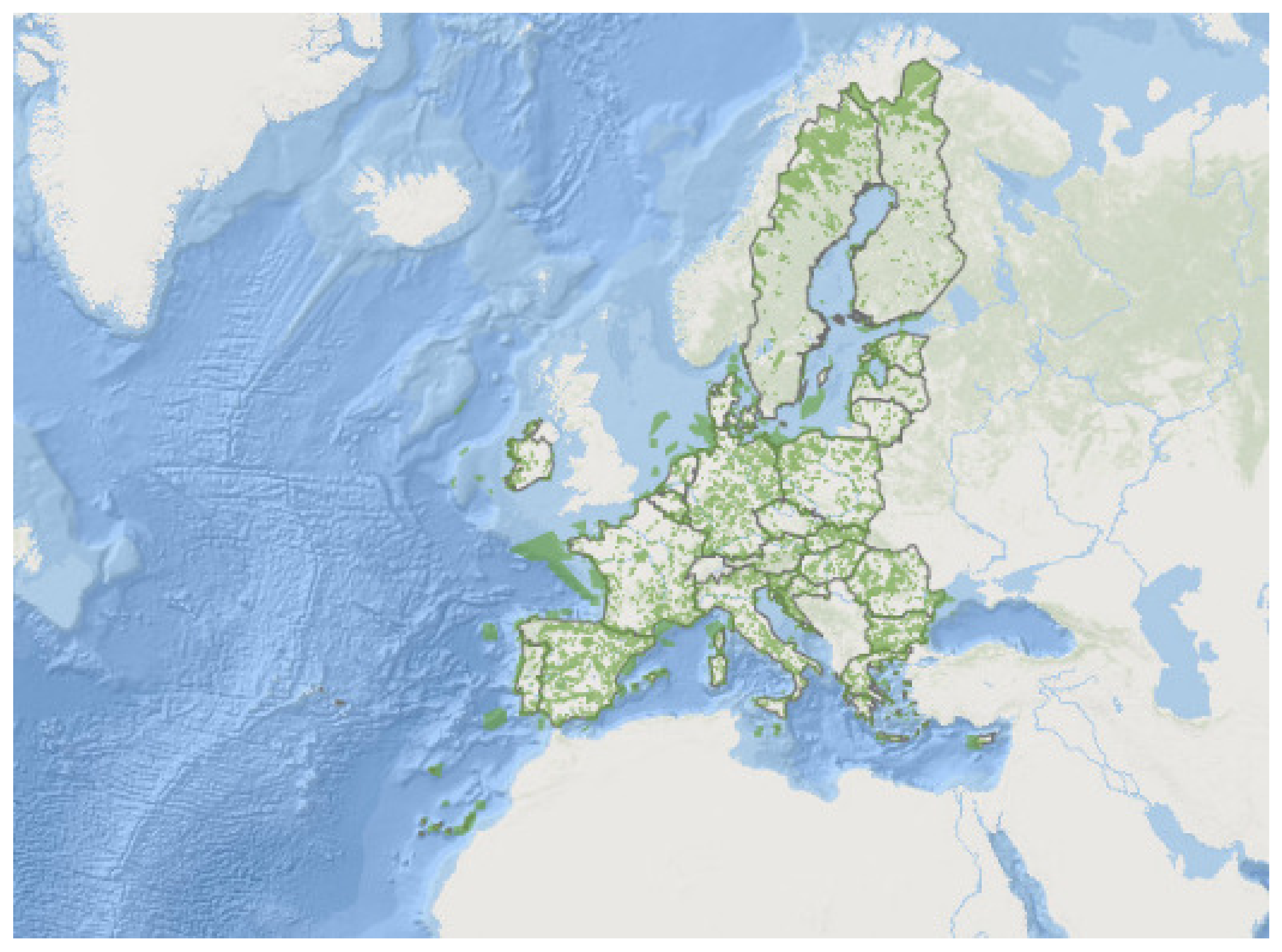

2.1. Tourism in Protected Areas

2.2. Pressures Applied on Ecosystems Due to Unsustainable Tourism

- Low-priced transportation tickets and travelling opportunities;

- An abundance of bed and breakfast accommodation, as well as several other tourists’ facilities;

- Political phenomena, such as war or terrorist attacks, that disfavor certain destinations;

- The expansion of the Internet, through which information is easily obtained and experiences are shared on various platforms [28].

- Inclusive and sustainable economic growth: 8, 9, 10 and 17;

- Social inclusiveness, employment and poverty reduction:1, 3, 4, 5, 8 and 10;

- Resources regulation, environmental protection and climate change: 6,7, 8, 11, 12, 13, 14, and 15;

- Cultural heritage and diversity: 8, 11, and 12;

- Peace and security: 16.

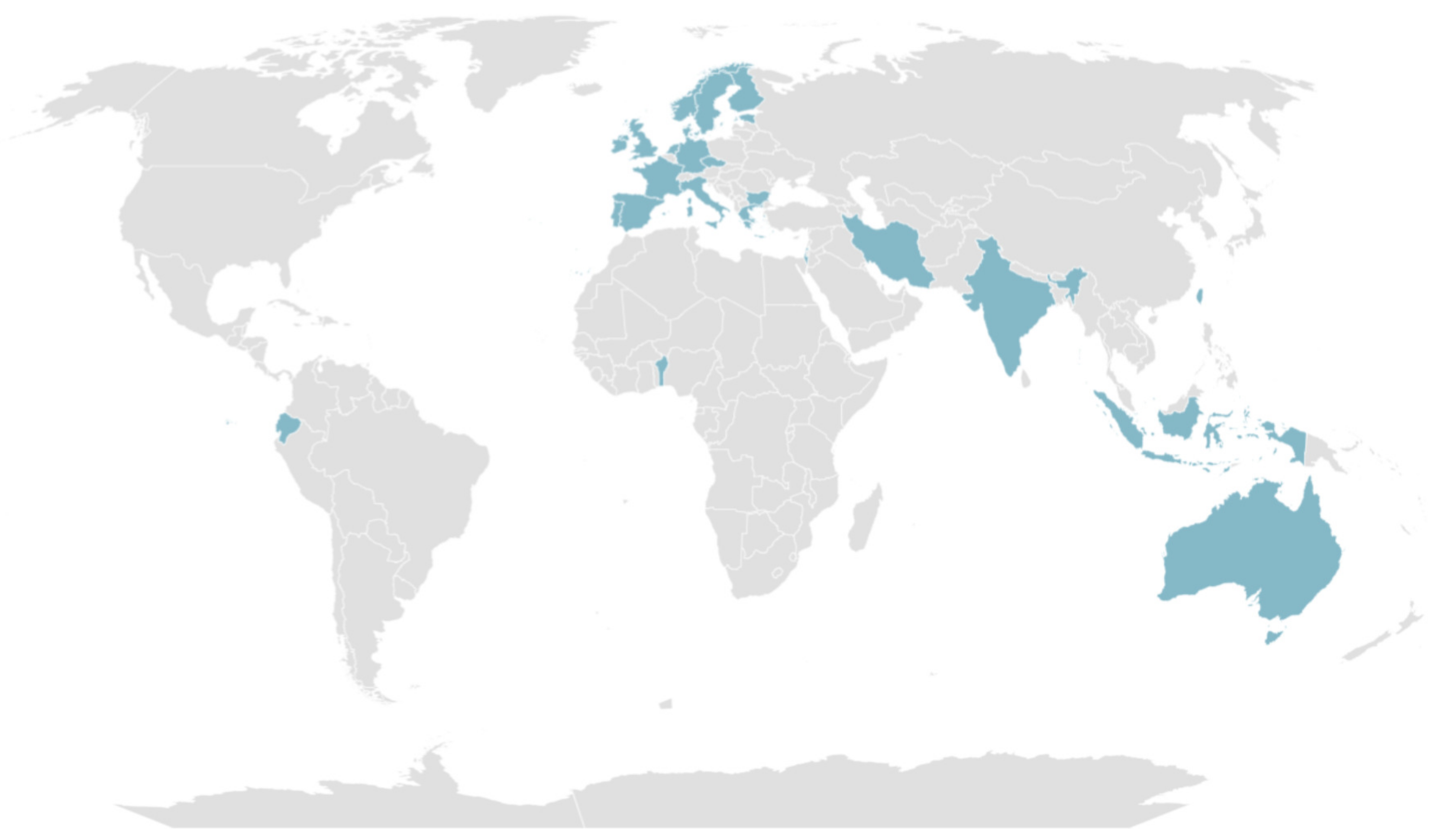

3. State-of-the-Art Research

3.1. Non-Market Economic Valuation Methods

3.2. The Travel Cost Method

3.2.1. Limitations of the Travel Cost Method

- The number of trips to the area;

- Demographics;

- TC;

- Time spent travelling.

- Time spent at the destination;

- Other sites visited during the same trip;

- Visiting purpose;

- Overall satisfaction (usually referring to environmental quality).

- ○

- Travel duration: The time spent travelling to a destination can be seen as part of the trip’s expenditures by time-constrained individuals, whereas others may benefit from a scenery journey.

- ○

- Multi-purpose and multi-destination trip: When visiting the examined site is part of a trip that involves several other destinations, there are difficulties in calculating the TC of interest. When the overall TC is allocated to different destinations, the partial cost drastically decreases.

- ○

- Substitute destinations: The presence of other destinations, even of the same type as the one ultimately visited, actually adds value to the latter. So, given two different travelers covering the same distance, the one with access to substitutes could value the preferred destination more.

- ○

- Other expenditures: In addition to transportation costs, there are several others, such as parking fees, vehicle maintenance expenses, as well as food and accommodation costs.

3.2.2. The Opportunity Cost of Time

3.3. Global Experience

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- John, C.M. Biodiversity Conservation Through Protected Areas Supports Healthy Ecosystems and Resilience to Climate Change and Other Disturbances. Imperiled Encycl. Conserv. 2022, 423–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmunds, P.J.; Lasker, H.R. Portfolio effects and functional redundancy contribute to the maintenance of octocoral forests on Caribbean reefs. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 7106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinclair, M.; Ghermandi, A.; Signorello, G.; Giuffrida, L.; De Salvo, M. Valuing Recreation in Italy’s Protected Areas Using Spatial Big Data. Ecol. Econ. 2022, 200, 107526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennerley, A.; Wood, L.E.; Luisetti, T.; Ferrini, S.; Lorenzoni, I. Economic impacts of jellyfish blooms on coastal recreation in a UK coastal town and potential management options. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2022, 227, 106284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klohmann, C.A.; Padilla-Gamiño, J.L. Pathogen Filtration: An Untapped Ecosystem Service. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 921451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhopadhyay, P.; Ghosh, S.; Da Costa, V.; Pednekar, S. Recreational value of coastal and marine ecosystems in India: A macro approach. Tour. Mar. Environ. 2020, 15, 11–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawrath, M.; Elsey, H.; Dallimer, M. Why cultural ecosystem services matter most Exploring the pathways linking greenspaces and mental health in a low-income country. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 806, 150551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subiza-Pérez, M.; Vozmediano, L.; Juan, C.S. Green and blue settings as providers of mental health ecosystem services: Comparing urban beaches and parks and building a predictive model of psychological restoration. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2020, 204, 103926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trovato, M.R.; Micalizzi, P.; Giuffrida, S. Assessment of landscape co-benefits in natura 2000 site management plans. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zambrano-Monserrate, M.A.; Silva-Zambrano, C.A.; Ruano, M.A. The economic value of natural protected areas in Ecuador: A case of Villamil Beach National Recreation Area. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2018, 157, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houngbeme, D.J.L.; Igue, C.B.; Cloquet, I. Estimating the value of beach recreation in Benin. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2021, 46, 390–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kathleen, S. Valuing Environmental Goods and Services: An Economic Perspective. In A Primer on Nonmarket Valuation, 2nd ed.; Springer Science+Business Media: Berlin, Germany, 2017; pp. 1–26. Available online: http://www.springer.com/series/5919 (accessed on 17 February 2023).

- Baggethun, E.G. Ethical Considerations Regarding Valuation of Ecosystem Services. In Les Services Écosystémiques Dans les Espaces Agricoles. Paroles de Chercheur(e)s; HAL: Bengaluru, India, 2020; pp. 139–154. [Google Scholar]

- Roussel, S.; Tardieu, L. Non-market Valuation. In Encyclopedia of Law and Economics; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, S.Y.; Gao, M.; Kim, H.; Shah, K.J.; Pei, S.L.; Chiang, P.C. Advances and challenges in sustainable tourism toward a green economy. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 635, 452–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorin, F.; Sivarajah, U. Exploring Circular economy in the hospitality industry: Empirical evidence from Scandinavian hotel operators. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2021, 21, 265–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, C.; Florido, C.; Jacob, M. Circular economy contributions to the tourism sector: A critical literature review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zorpas, A.A.; Navarro-Pedreño, J.; Panagiotakis, I.; Dermatas, D. Steps forward to adopt a circular economy strategy by the tourism industry. Waste Manag. Res. 2021, 39, 889–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Cabrera, J.; López-Del-pino, F. The 10 most crucial circular economy challenge patterns in tourism and the effects of COVID-19. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buongiorno, A.; Intini, M. Sustainable tourism and mobility development in natural protected areas: Evidence from Apulia. Land Use Policy 2021, 101, 105220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.J.; Lee, D.K.; Kim, C.K. Spatial tradeoff between biodiversity and nature-based tourism: Considering mobile phone-driven visitation pattern. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2020, 21, e00899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocchi, L.; Cortina, C.; Paolotti, L.; Boggia, A. Recreation vs conservation in Natura 2000 sites: A spatial multicriteria approach analysis. Land Use Policy 2020, 99, 105094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiliopoulou, K.; Dimitrakopoulos, P.G.; Brooks, T.; Kelaidi, G. The Natura 2000 network and the ranges of threatened species in Greece. Biodivers. Conserv. 2021, 30, 945–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, D.B.; Lawton, L.J. A new visitation paradigm for protected areas. Tour Manag. 2017, 60, 140–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pásková, M.; Wall, G.; Zejda, D.; Zelenka, J. Tourism carrying capacity reconceptualization: Modelling and management of destinations. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2021, 21, 100638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sørensen, F.; Bærenholdt, J.O. Tourist practices in the circular economy. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 85, 103027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boluk, K.A.; Cavaliere, C.T.; Higgins-Desbiolles, F. A critical framework for interrogating the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals 2030 Agenda in tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 847–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertocchi, D.; Camatti, N.; Giove, S.; van der Borg, J. Venice and overtourism: Simulating sustainable development scenarios through a tourism carrying capacity model. Sustainability 2020, 12, 512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihalic, T. Concpetualising overtourism: A sustainability approach. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 84, 103025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, R.W. Tourism carrying capacity research: A perspective article. Tour. Rev. 2020, 75, 207–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Börger, T.; Campbell, D.; White, M.P.; Elliott, L.R.; Fleming, L.E.; Garrett, J.K.; Hattam, C.; Hynes, S.; Lankia, T.; Taylor, T. The value of blue-space recreation and perceived water quality across Europe: A contingent behaviour study. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 771, 145597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leh, F.C.; Mokhtar, F.Z.; Rameli, N.; Ismail, K. Measuring Recreational Value Using Travel Cost Method (TCM): A Number of Issues and Limitations. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2018, 8, 1381–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolfe, J.; Scarborough, H.; Blackwell, B.; Blackley, S.; Walker, C. Estimating economic values for beach and foreshore assets and preservation against future climate change impacts in Victoria, Australia. Australas. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 28, 169–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tribe, J. The Economics of Recreation, Leisure and Tourism, 4th ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- George, P.R. Travel Cost Models. In A Primer on Nonmarket Valuation, 2nd ed.; Patricia, C.A., Thomas, B.C., Kevin, B.J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 187–234. [Google Scholar]

- Soares, J.O. The Recreational Value of Azibo Beaches: A Case Study in the Interior North of Portugal. Rev. Port. Estud. Reg. 2021, 58, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascoe, S. Recreational beach use values with multiple activities. Ecol. Econ. 2019, 160, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deely, J.; Hynes, S.; Cawley, M. Overseas visitor demand for marine and coastal tourism. Mar. Policy 2022, 143, 105176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tienhaara, A.; Lankia, T.; Lehtonen, O.; Pouta, E. Heterogeneous preferences towards quality changes in water recreation: Latent class model for contingent behavior data. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2021, 35, 100386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juutinen, A.; Immerzeel, B.; Pouta, E.; Lankia, T.; Artell, J.; Tolvanen, A.; Ahtiainen, H.; Vermaat, J. A comparative analysis of the value of recreation in six contrasting Nordic landscapes using the travel cost method. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2022, 39, 100528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lankia, T.; Neuvonen, M.; Pouta, E. Effects of water quality changes on the recreation benefits of swimming in Finland: Combined travel cost and contingent behavior model. Water Resour. Econ. 2019, 25, 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riesti, T.; Indah, S. Characteristics and Economic Value of Tourism Services in Coastal Area of Gunungkidul Regency. E3S Web Conf. 2018, 73, 10026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, C.M.; Lin, C.C.; Lin, S.P. Study on the appraisal of tourism demands and recreation benefits for Nanwan Beach, Kenting, Taiwan. Environments 2018, 5, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menendez-Carbo, S.; Ruano, M.A.; Zambrano-Monserrate, M.A. The economic value of Malecón 2000 in Guayaquil, Ecuador: An application of the travel cost method. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 36, 100727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kheyri, E.; Morovati, M.; Neshat, A.; Siahati, G. Economic valuation of natural promenades in Iran using zonal travel costs method (Case study area: Gahar Lake in Lorestan Province in western Iran). PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0241396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latinopoulos, D. The role of ecotourism in the Prespa National Park in Greece. Evidence from a travel cost method and hoteliers’ perceptions. J. Environ. Manag. Tour. 2019, 10, 1731–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rousseau, S.; Fuertes, A.T. Country borders and the value of scuba diving in an estuary. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2020, 184, 105002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hynes, S.; Burger, R.; Tudella, J.; Norton, D.; Chen, W. Estimating the costs and benefits of protecting a coastal amenity from climate change-related hazards: Nature based solutions via oyster reef restoration versus grey infrastructure. Ecol. Econ. 2022, 194, 107349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clara, I.; Dyack, B.; Rolfe, J.; Alice, N.; Borg, D.; Povilanskas, R.; Brito, A.C. The value of coastal lagoons: Case study of recreation at the Ria de Aveiro, Portugal in comparison to the Coorong, Australia. J. Nat. Conserv. 2018, 43, 190–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavee, D.; Menachem, O. Economic valuation of the existence of the southwestern basin of the Dead Sea in Israel. Land Use Policy 2018, 71, 160–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouso, S.; Ferrini, S.; Turner, R.K.; Uyarra, M.C.; Borja, Á. Financial inputs for ecosystem service outputs: Beach recreation recovery after investments in ecological restoration. Front. Mar. Sci. 2018, 5, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heagney, E.C.; Rose, J.M.; Ardeshiri, A.; Kovač, M. Optimising recreation services from protected areas—Understanding the role of natural values, built infrastructure and contextual factors. Ecosyst. Serv. 2018, 31, 358–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heagney, E.C.; Rose, J.M.; Ardeshiri, A.; Kovac, M. The economic value of tourism and recreation across a large protected area network. Land Use Policy 2019, 88, 104084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, M.; Mayer, M.; Woltering, M.; Ghermandi, A. Valuing nature-based recreation using a crowdsourced travel cost method: A comparison to onsite survey data and value transfer. Ecosyst. Serv. 2020, 45, 101165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Tourism Type | Traits | Origin |

|---|---|---|

| Sustainable tourism | Considers social, economic, and environmental needs of given community and visitors | World Tourism Organization |

| Aims to improvement | ||

| Ecotourism | Stresses the importance of knowledge and education for everyone involved in a given area (stakeholders and visitors) | The International Ecotourism Society, 2015 |

| Volunteer tourism | Working holiday for social and environmental causes | Not explicitly determined |

| Covers basic expenses | ||

| Responsible tourism | Promotes activities that improve the economy and conserve the cultural heritage of a protected area | Cape Town Declaration, 2002, Goodwin |

| Geotourism | Involves environment, agriculture, culture, local cuisine, etc. | National Geographic |

| Aims to improve the geographical character of protected area |

| Type | Method | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Stated preference | Willingness to pay (WTP) | The total valuation is estimated by multiplying the average WTP by the total number of users. It is found that respondents tend to over-report their WTF under hypothetical questions. |

| Contingent valuation (CV) | Users are presented with one or more hypothetical scenarios in which they are asked to express their WTP, for a specific improvement in environmental quality or conservation of a natural resource. The responses are then used to estimate the overall economic value of the environmental good or service. Suitable for sites with aesthetic features. | |

| Choice experiment (CE) | Users choose between different alternatives presented to them, each with a different combination of attributes regarding environmental quality or conservation policies. | |

| Revealed preference | Mitigation behaviour (MBV) | MBV is based on estimated costs related to avoiding or reducing exposure to environmental risks (e.g., a potential flood). |

| Hedonic pricing (HPM) | HPM involves gathering data on price variations, pinpointing their origin, and estimating the impact of the environment on them. | |

| TC method (TCM) | TCM is based on the assumption that the travel expenditures to a site are related to visitor’s valuation of it. Suitable for tourist destinations. | |

| Dose–response (DR) | DR data are often utilized to estimate the impact of environmental quality (e.g., air pollution) on human health. | |

| Replacement cost technique | Mostly used in damage assessment, this method estimates the costs of replacing lost or damaged services or goods. |

| ITCM | ZTCM |

|---|---|

| Specifies individual’s traits | Uses average data per zone |

| Produces more accurate demand function | Avoids outliers |

| Requires significant sample | Deals with lack of data |

| Assumes that an individual’s characteristics affect travelling decisions | Considers certain socioeconomic variables statistically insignificant |

| Robust estimations require variation in visitation rate | Robust estimations require an adequate number of zones |

| Year | Authors | Country | Type of Ecosystem | Valuation Method | Data | Consumer Surplus per Trip/Visitor (EUR) | Analysis | Annual Economic Value (EUR) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-European Countries | ||||||||

| 2018 | Riesti and Indah [42] | Indonesia | 6 beaches | ITCM | On-site survey | - | Log-linear model | 190 thousand |

| 2018 | Dong et al. [43] | Taiwan | Bay | ITCM | On-site survey | 234 | Truncated Poisson model, truncated binomial distribution model, on-site Poisson model | 221 million |

| 2020 | Mukhopadhyay et al. [6] | India | Coastal zones | ZTCM | On-site survey | - | Panel regression | 47 billion |

| 2020 | Kheyri et al. [45] | Iran | Lake | ZTCM | On-site survey | 74 | Linear regression | 1.7 million |

| 2018 | Lavee and Menachem [50] | Israel | Lake | ITCM + CVM | On-site, online, telephone surveys | 17 | Linear regression | 24.4 million |

| 2021 | Houngbeme et al. [11] | Benin | Beach | ITCM | On-site survey | 0.76 | Poisson model, negative binomial regression | - |

| 2018 | Zambrano-Monserrate et al. [10] | Ecuador | Beach | ITCM | On-site survey | 15 | Zero-truncated negative binomial regression | 18 million |

| 2020 | Menendez-Carbo et al. [44] | Ecuador | Urban park | ITCM | Online survey | 14 | Zero-truncated negative binomial regression | 271–334 million |

| 2019 | Pascoe [37] | Australia | Beach | ITCM | Online survey | 15.5 | Hurdle model | - |

| 2021 | Rolfe et al. [33] | Australia | 5 coastal towns | ITCM + choice experiment | On-site survey | 40 | Advanced logit models | - |

| 2018 | Heagney et al. [52] | Australia | Various | ITCM | Telephone survey | 28 | Random effects ordered logit model | 3 billion |

| European Countries | ||||||||

| 2018 | Clara et al. [49] | Australia + Portugal | Lagoon | ITCM + CVM | On-site survey | 130 | Negative binomial model | - |

| 2021 | Soares [36] | Portugal | 2 beaches | ZTCM | On-site survey | 23–114 | Linear, linear-log, log-linear, log-log models | 3.6 million |

| 2018 | Pouso et al. [51] | Spain | 3 beaches | ITCM + partial cost–benefit analysis | On-site survey | 7 | Poisson model | 3.5 million |

| 2021 | Trovato et al. [9] | Italy | Coastal zone | ITCM + CVM | On-site survey | - | Linear regression | 3 million |

| 2022 | Sinclair et al. [3] | Italy | Various | CTCM | Geotagged photographs | 6–87 | Zero-truncated Poisson model | 0.3–174 million |

| 2019 | Latinopoulos [46] | Greece | Lake | Hybrid TC | On-site survey | 59 | Log-linear regression | 0.2 million |

| 2022 | Hynes et al. [48] | Ireland | Bay | ITCM + cost–benefit analysis | On-site survey | 11 | Negative binomial model | 0.6 million |

| 2022 | Deely et al. [38] | Ireland | Coastal zones | ITCM | On-site survey | 295 | Logit model, negative binomial model | - |

| 2022 | Kennerley et al. [4] | UK | Coastal zone | ITCM + CVM | On-site survey | - | Negative binomial regression | - |

| 2020 | Sinclair et al. [54] | Germany | Various | CTCM | Geotagged photographs | 17–35 | Log-log ordinary least squares regression | 1.67 billion |

| 2020 | Rousseau and Tejerizo Fuertes [47] | the Netherlands | Estuary | ITCM + choice experiment | Online survey | 108–197 | Log-linear regression | 22 million |

| 2019 | Lankia et al. [41] | Finland | Coastal zones | ITCM + CVM | Online, mailed paper survey | 16 | Poisson model, negative binomial regression | - |

| 2021 | Tienhaara et al. [39] | Finland | Lake | ITCM + CVM | On-site survey | 71 | Poisson model | - |

| 2022 | Juutinen et al. [40] | 4 Nordic Countries | Various | ITCM | On-site survey | 21–64 | Negative binomial models | 3.1–120.8 million |

| 2021 | Börger et al. [31] | 14 EU countries | Blue spaces | ITCM + CVM | Online survey | 41 | Multivariate Poisson lognormal regression | 631 billion |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Skarakis, N.; Skiniti, G.; Tournaki, S.; Tsoutsos, T. Necessity to Assess the Sustainability of Sensitive Ecosystems: A Comprehensive Review of Tourism Pressures and the Travel Cost Method. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12064. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151512064

Skarakis N, Skiniti G, Tournaki S, Tsoutsos T. Necessity to Assess the Sustainability of Sensitive Ecosystems: A Comprehensive Review of Tourism Pressures and the Travel Cost Method. Sustainability. 2023; 15(15):12064. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151512064

Chicago/Turabian StyleSkarakis, Nikolaos, Georgia Skiniti, Stavroula Tournaki, and Theocharis Tsoutsos. 2023. "Necessity to Assess the Sustainability of Sensitive Ecosystems: A Comprehensive Review of Tourism Pressures and the Travel Cost Method" Sustainability 15, no. 15: 12064. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151512064

APA StyleSkarakis, N., Skiniti, G., Tournaki, S., & Tsoutsos, T. (2023). Necessity to Assess the Sustainability of Sensitive Ecosystems: A Comprehensive Review of Tourism Pressures and the Travel Cost Method. Sustainability, 15(15), 12064. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151512064