Review of Crisis Management Frameworks in Tourism and Hospitality: A Meta-Analysis Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- What are the main crisis management frameworks in the tourism and hospitality literature?

- (2)

- To what type of crisis are crisis management frameworks applied?

- (3)

- What are the research methodologies employed?

- (4)

- What lessons can be drawn from existing crisis management frameworks and their applicability to the COVID-19 pandemic crisis?

2. Literature Review

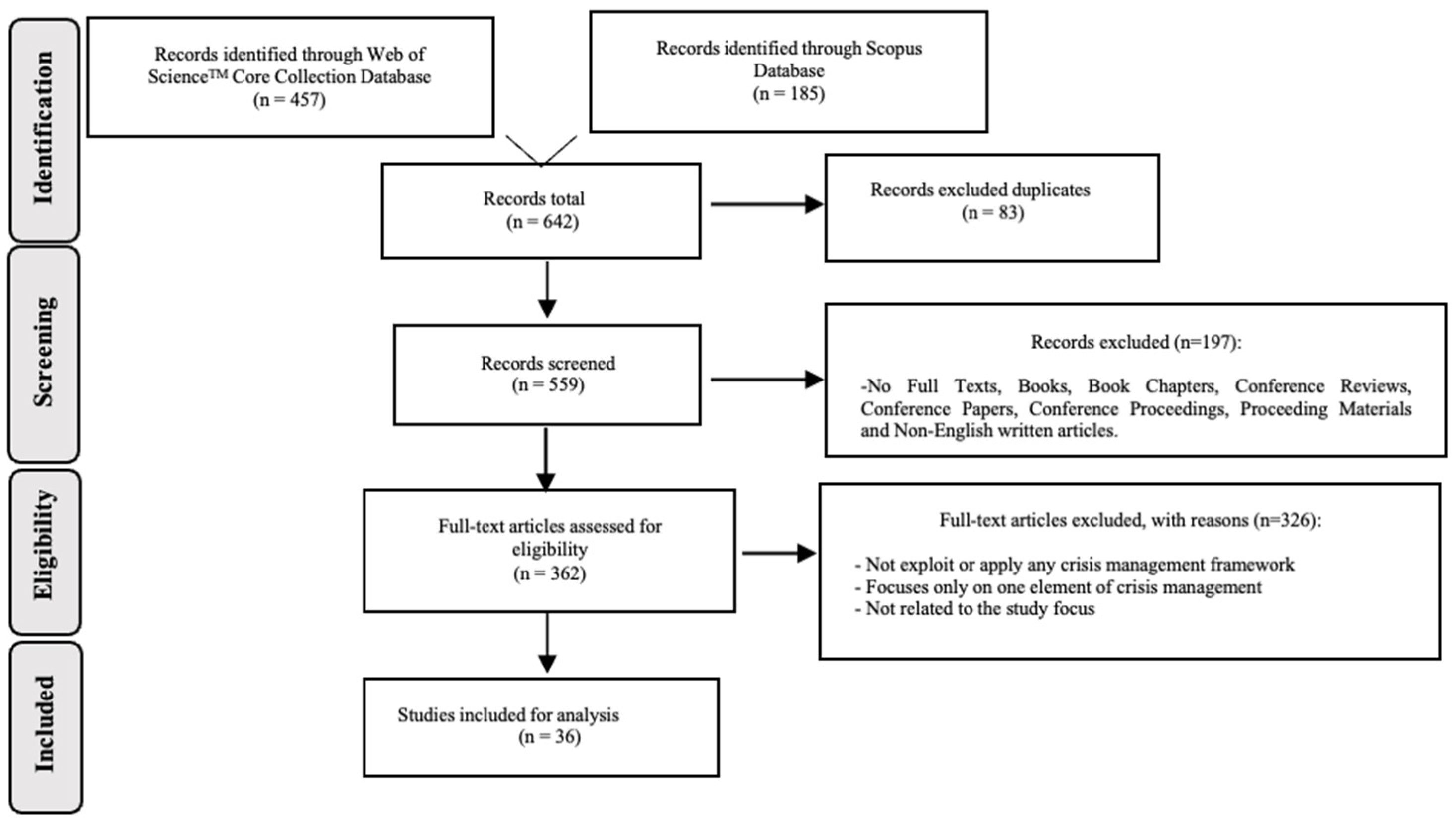

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

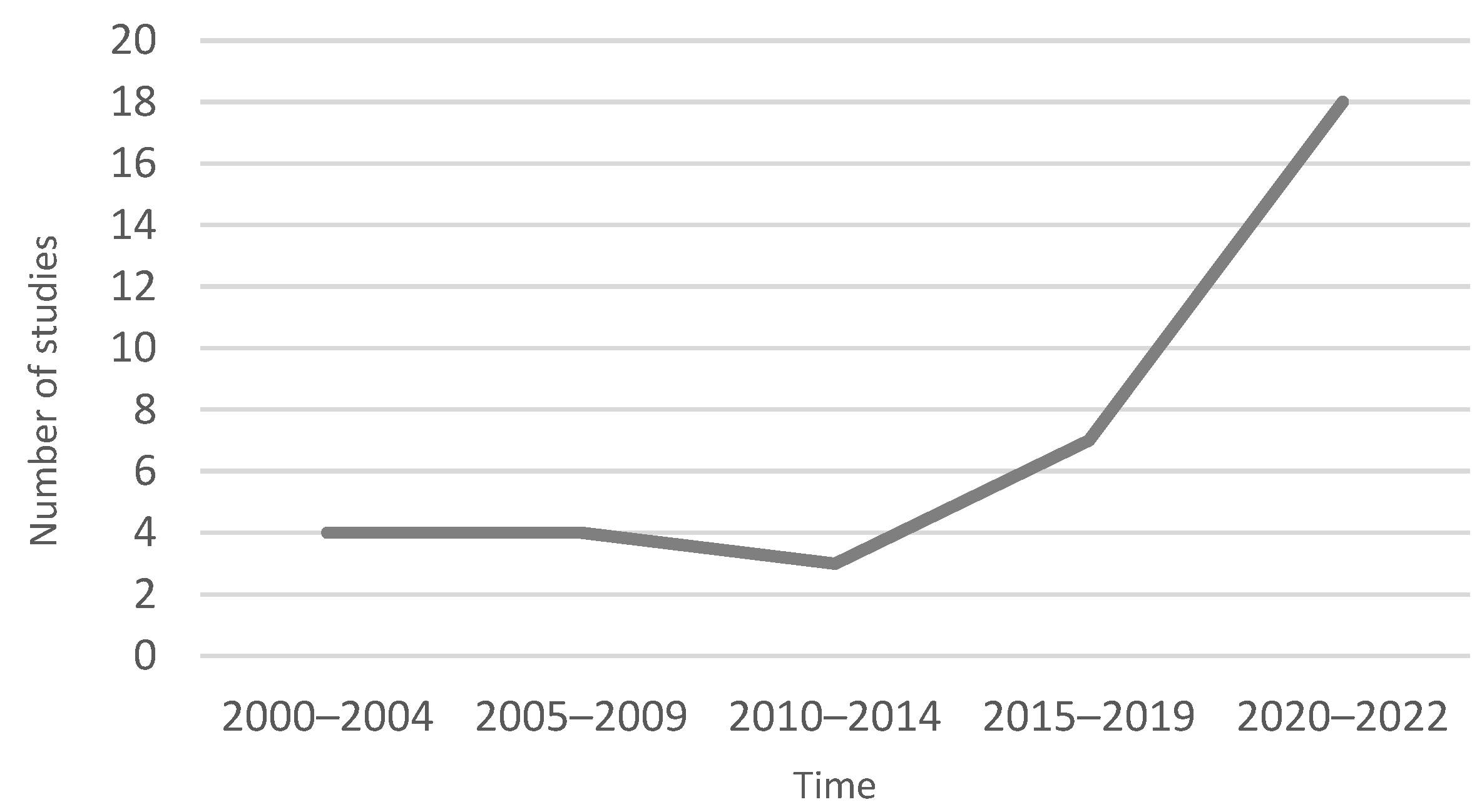

4.1. Studies, Journals and Authors

4.2. Type of Crisis and Type of Study Analysed

4.3. Methodological Design of Previous Research

| Approach | Method | N. Studies | Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Qualitative | Interview | 9 | [38,42,43,47,52,53,54,55,60] |

| Interview + secondary data | 4 | [17,41,57,58] | |

| Interview + on-site observation | 1 | [61] | |

| Interview + on-site observation + secondary data | 2 | [39,56] | |

| Literature | 14 | [7,8,10,11,12,15,26,30,42,44,45,46,49,50] | |

| Secondary data | 4 | [48,51,62,63] | |

| Quantitative | Survey | 1 | [59] |

| Geospatial data | 1 | [40] |

4.4. Crisis Management Frameworks in Tourism and Hospitality

COVID-19 Crisis Management Frameworks

5. Critical Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Journal | No. Studies | H-Index | Country |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tourism Management | 7 | 199 | United Kingdom |

| Annals of Tourism Research | 3 | 171 | United Kingdom |

| Current Issues in Tourism | 3 | 74 | United Kingdom |

| International Journal of Hospitality Management | 3 | 122 | United Kingdom |

| International Journal of Tourism Research | 3 | 58 | United Kingdom |

| Journal of Travel and Tourism Marketing | 3 | 73 | United States |

| African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure | 1 | 11 | South Africa |

| Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research | 1 | 37 | United Kingdom |

| Communications—Scientific Letters of the University of Zilina | 1 | 21 | Slovakia |

| Cornell Hospitality Quarterly | 1 | 75 | United States |

| European Journal of Tourism Research | 1 | 16 | Bulgaria |

| Geographia Technica | 1 | 11 | Romania |

| Journal of Destination Marketing and Management | 1 | 39 | United Kingdom |

| Journal of General Management | 1 | 20 | United Kingdom |

| Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Insights | 1 | 70 | United States |

| Journal of Park and Recreation Administration | 1 | - | United States |

| Sustainability | 1 | 85 | Switzerland |

| Tourism Analysis | 1 | 36 | United States |

| Tourism Review | 1 | 32 | United Kingdom |

| Worldwide Hospitality and Tourism Themes | 1 | 20 | United Kingdom |

Appendix B

| Total | Type | Empirical | Conceptual | Mixed | Review |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Conflict | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | COVID-19 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 0 |

| 1 | Cyclone | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 3 | Earthquake | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 1 | Forest fire | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | Health-related crisis | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | Political | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | Shipping accident | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | Tsunami | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | Natural disasters (multiple) | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| 12 | Crises (multiple) | 1 | 3 | 1 | 7 |

| 36 | Total | 14 | 6 | 8 | 8 |

Appendix C

| Phases | Components | Structure | Type of Crisis | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Framework | Pre-Crisis | Crisis | Post-Crisis | Risk Assessment | Contingency Plans | Mid-Crisis Management | Crisis Communications | Evaluation and Review | Flexibility | Stigma | KM | GIS | GPS | SC | DC | RE | SE | CY | CS | ND |

| [15] | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||

| [26] | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||

| [62] | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||

| [57] | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| [59] | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| [30] | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||

| [44] | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| [55] | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||

| [48] | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||

| [46] | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||||

| [58] | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| [47] | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||

| [61] | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||

| [56] | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

References

- Pforr, C.; Hosie, P. Crisis management in tourism: Preparing for recovery. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2008, 23, 249–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Sausmarez, N. Crisis management for the tourism sector: Preliminary considerations in policy development. Tour. Hosp. Plan. Dev. 2004, 1, 157–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Wang, X. COVID-19 two years on: A review of COVID-19-related empirical research in major tourism and hospitality journals. Int. J. Contemp. Manag. 2023, 35, 743–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bundy, J.; Pfarrer, M.D.; Short, C.E.; Coombs, W.T. Crises and Crisis Management: Integration, Interpretation, and Research Development. J. Manag. 2017, 43, 1661–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenker, S.; Kock, F. The coronavirus pandemic—A critical discussion of a tourism research agenda. Tour. Manag. 2020, 81, 104164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wut, T.M.; Xu, B.; Wong, H.S.M. A 15-year Review of “Corporate Social Responsibility Practices” Research in the Hospitality and Tourism Industry. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2022, 23, 240–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mair, J.; Ritchie, B.W.; Walters, G. Curr. Issues Tour. Towards a research agenda for post-disaster and post-crisis recovery strategies for tourist destinations: A narrative review. Curr. Issues Tour. 2016, 19, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, B.W.; Jiang, Y. A review of research on tourism risk, crisis and disaster management: Launching the annals of tourism research curated collection on tourism risk, crisis and disaster management. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 79, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Ritchie, B.W.; Benckendorff, P. Bibliometric visualisation: An application in tourism crisis and disaster management research. Curr. Issues Tour. 2019, 22, 1925–1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wut, T.M.; Xu, B.; Wong, S.M. Crisis management research (1985–2020) in the hospitality and tourism industry: A review and research agenda. Tour. Manag. 2021, 85, 104307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leta, S.D.; Chan, I.C.C. Learn from the past and prepare for the future: A critical assessment of crisis management research in hospitality. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 95, 102915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berbekova, A.; Uysal, M.; Assaf, A.G. A thematic analysis of crisis management in tourism: A theoretical perspective. Tour. Manag. 2021, 86, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, B.W.; Crotts, J.C.; Zehrer, A.; Volsky, G.T. Understanding the effects of a tourism crisis: The impact of the BP oil spill on regional lodging demand. J. Travel Res. 2013, 53, 12–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laws, E.; Prideaux, B. Crisis management: A suggested typology. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2005, 19, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faulkner, B. Towards a framework for tourism disaster management. Tour. Manag. 2001, 22, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennington-Gray, L. Reflections to move forward: Where destination crisis management research needs to go. Tour. Manag. Perspectives 2018, 25, 136–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speakman, M.; Sharpley, R. A chaos theory perspective on destination crisis management: Evidence from Mexico. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2012, 1, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backer, E.; Ritchie, B.W. VFR travel: A viable market for tourism crisis and disaster recovery? Int. J. Tour. Res. 2017, 19, 400–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S.; Scott, D.; Hall, C.M. Pandemics, tourism and global change: A rapid assessment of COVID-19. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 29, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, A.; Pennington-Gray, L. The Role of Social Media in International Tourist’s Decision Making. J. Travel Res. 2015, 54, 584–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M. Crisis events in tourism: Subjects of crisis in tourism. Curr. Issues Tour. 2010, 13, 401–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutzner, D. Environmental change, resilience, and adaptation in nature-based tourism: Conceptualizing the social-ecological resilience of birdwatching tour operations. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 1142–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigala, M. Tourism and COVID-19: Impacts and Implications for Advancing and Resetting Industry and Research. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 117, 312–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tourism and COVID-19—Unprecedented Economic Impacts. Available online: https://www.unwto.org/tourism-and-covid-19-unprecedented-economic-impacts (accessed on 27 November 2022).

- Research Updates on COVID-19: Long COVID, Vaccine Side Effects, Variant Updates and More. Available online: https://princetonlongevitycenter.com/long-covid-vaccine-side-effect-variants-and-more/ (accessed on 24 April 2023).

- Ritchie, B.W. Chaos, crises and disasters: A strategic approach to crisis management in the tourism industry. Tour. Manag. 2004, 25, 669–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lew, A.A.; Cheer, J.M.; Haywood, M.; Brouder, P.; Salazar, N.B. Visions of travel and tourism after the global COVID-19 transformation of 2020. Tour. Geogr. 2020, 22, 455–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana, G. Crisis management and tourism. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2004, 15, 299–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moe, T.L.; Pathranarakul, P. An integrated approach to natural disaster management: Public project management and its critical success factors. Disaster Prev. Manag. Int. J. 2006, 15, 396–413. [Google Scholar]

- Pennington-Gray, L. Developing a destination disaster impact framework. Tour. Anal. 2014, 19, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEntire, D.A.; Fuller, C.; Johnston, C.W.; Weber, R. A Comparison of Disaster Paradigms: The Search for a Holistic Policy Guide. Public Adm. Rev. 2002, 62, 267–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denyer, D.; Tranfield, D. Using qualitative research synthesis to build an actionable knowledge base. Manag. Decis. 2006, 44, 213–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchanan, D.; Bryman, A. The SAGE Handbook of Organizational Research Methods; SAGE Publications Lda.: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Mulrow, C.D. Rationale for systematic reviews. BMJ 1994, 309, 597–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tranfield, D.; Denyer, D.; Smart, P. Towards a Methodology for Developing Evidence-Informed Management Knowledge by Means of Systematic Review. Br. J. Manag. 2003, 14, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2009, 62, e1–e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mongeon, P.; Paul-Hus, A. The journal coverage of Web of Science and Scopus: A comparative analysis. Scientometrics 2016, 106, 213–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.; Nozu, K.; Zhou, Q. Tourism Stakeholder Perspective for Disaster-Management Process and Resilience: The Case of the 2018 Hokkaido Eastern Iburi Earthquake in Japan. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novelli, M.; Burgess, L.G.; Jones, A.; Ritchie, B.W. ‘No Ebola…still doomed’—The Ebola-induced tourism crisis. Ann. Tour. Res. 2018, 70, 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, I.C.; Mathews, A.J.; Liu, H.L.; Rose, N. A historical geospatial analysis of severe weather events in oklahoma state parks: A park management perspective. J. Park Recreat. Adm. 2021, 39, 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, G.A.; Ritchie, B.W. A Farming Crisis or a Tourism Disaster? An Analysis of the Foot and Mouth Disease in the UK. Curr. Issues Tour. 2003, 6, 150–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Gani, A.; Singh, R.; Najar, A.H. Rebuilding Tourist destinations from Crisis: A comparative Study of Jammu and Kashmir and Assam, India. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2021, 13, 437–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niininen, O.; Gatsou, M. Crisis Management—A Case Study from the Greek Passenger Shipping Industry. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2008, 23, 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agustan, A.; Roza, D.; Kausar, K. Towards a framework for disaster risk reduction in Indonesia’s urban tourism industry based on spatial information. Geogr. Tech. 2019, 14, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Ritchie, B.W.; Verreynne, M.-L. Building tourism organizational resilience to crises and disasters: A dynamic capabilities view. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2019, 21, 882–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, M.V.; Boyd, S.W.; Nica, M. Towards a post-conflict tourism recovery framework. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 84, 102940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burhan, M.; Salam, M.T.; Hamdan, O.A.; Tariq, H. Crisis management in the hospitality sector SMEs in Pakistan during COVID-19. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 98, 103037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, F.; Xiao, Q.; Chon, K. COVID-19 and China’s Hotel Industry: Impacts, a Disaster Management Framework, and Post-Pandemic Agenda. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 90, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazurek, M. The innovative approach to risk management as a part of destination competitiveness and reputation. Communications 2020, 22, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estevão, C.; Costa, C. Natural disaster management in tourist destinations: A systematic literature review. Eur. J. Tour. Res. 2020, 25, 2502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paraskevas, A.; Quek, M. When Castro seized the Hilton: Risk and crisis management lessons from the past. Tour. Manag. 2019, 70, 419–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derham, J.; Best, G.; Frost, W. Disaster recovery responses of transnational tour operators to the Indian Ocean tsunami. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2022, 24, 376–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fung, C.; Tsui, B.; Hon, A.H.Y. Crisis management: A case study of disease outbreak in the Metropark Hotel group. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2020, 25, 1062–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.; Nozu, K.; Cheung, T.O.L. Tourism and natural disaster management process: Perception of tourism stakeholders in the case of Kumamoto earthquake in Japan. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 23, 1864–1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filimonau, V.; De Coteau, D. Tourism resilience in the context of integrated destination and disaster management (DM2). Int. J. Tour. Res. 2020, 22, 202–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Ritchie, B.W.; Verreynne, M.L. Developing disaster resilience: A processual and reflective approach. Tour. Manag. 2021, 87, 104374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hystad, P.W.; Keller, P.C. Towards a destination tourism disaster management framework: Long-term lessons from a forest fire disaster. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodolica, V.; Spraggon, M.; Khaddage-Soboh, N. Air-travel services industry in the post-COVID-19: The GPS (Guard-Potentiate-Shape) model for crisis navigation. Tour. Rev. 2021, 76, 942–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Racherla, P.; Hu, C. A framework for knowledge-based crisis management in the hospitality and tourism industry. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2009, 50, 561–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Permatasari, M.G.; Mahyuni, L.P. Crisis management practices during theCOVID-19 pandemic: The case of anewly-opened hotel in Bali. J. Gen. Manag. 2022, 47, 180–190. [Google Scholar]

- Dayour, F.; Adongo, C.A.; Amuquandoh, F.E.; Adam, I. Managing the COVID-19 crisis: Coping and post-recovery strategies for hospitality and tourism businesses in Ghana. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2021, 4, 373–392. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.-C.; Tseng, Y.-P.; Petrick, J.F. Crisis Management Planning to Restore Tourism After Disasters. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2008, 23, 203–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prideaux, B. The Need to Use Disaster Planning Frameworks to Respond to Major Tourism Disasters Analysis of Australia’s Response to Tourism Disasters in 2001. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2004, 15, 281–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, J.C. Managing the Asian financial crisis: Tourist attractions in Singapore. J. Travel Res. 1999, 38, 177–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ichinosawa, J. Reputational disaster in Phuket: The secondary impact of the tsunami on inbound tourism. Disaster Prev. Manag. 2006, 15, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindell, M.K. Disaster studies. Sociopedia ISA 2011, 10, 4–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mistilis, N.; Sheldon, P. Knowledge management for tourism crises and disasters. Tour. Rev. Int. 2006, 10, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Brown, N.A.; Orchiston, C.; Rovins, J.E.; Feldmann-Jensen, S.; Johnston, D. An integrative framework for investigating disaster resilience within the hotel sector. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2018, 36, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cioccio, L.; Michael, E. Hazard or disaster: Tourism management for the inevitable in Northeast Victoria. Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crisis leadership—10 lessons from Sir Shackleton. Leadership Excellence (June 2010). Available online: https://www.stevefarber.com/wp-content/uploads/Leadership-Excellence-Mag-Farber.pdf (accessed on 30 April 2023).

- Faulkner, B.; Vikulov, S. Katherine, washed out one day, back on track the next: A post-mortem of a tourism disaster. Tour. Manag. 2001, 22, 331–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baggio, R. Symptoms of complexity in a tourism system. Tour. Anal. 2008, 13, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, B.H.; Twining-Ward, L. Reconceptualizing tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2004, 31, 274–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, B.; Carter, R.W.; De Lacy, T. Short-term Perturbations and Tourism Effects: The Case of SARS in China. Curr. Issues Tour. 2005, 8, 306–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Callaghan-Gordo, C.; Antó, J.M. COVID-19: The disease of the Anthropocene. Environ. Res. 2020, 187, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paraskevas, A.; Altinay, L. Signal detection as the first line of defence in tourism crisis management. Tour. Manag. 2013, 34, 158–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baktash, A.; Huang, A.; Velasco, E.M.; Farboudi, M.J.; Bahja, F. Agent-based modelling for tourism research. Curr. Issues Tour. 2022, 26, 2115–2127. [Google Scholar]

- Boavida-Portugal, I.; Ferreira, C.C.; Rocha, J. Where to vacation? An agent-based approach to modelling tourist decision-making process. Curr. Issues Tour. 2017, 20, 1557–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avraham, E. Destination image repair during crisis: Attracting tourism during the Arab Spring uprisings. Tour. Manag. 2015, 47, 224–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prideaux, B.; Thompson, M.; Pabel, A.; Cassidy, L. Managing climate change crisis events at the destination level. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 49, 451–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahyanto, I.; Pennington-Gray, L. Toward A Comprehensive Destination Crisis Resilience Framework. In Proceedings of the International Conference Travel and Tourism Research Association, Quebec, QC, Canada, 20–22 June 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Stephen, C. Rethinking pandemic preparedness in the Anthropocene. Healthc. Manag. Forum 2020, 33, 153–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study | Elements |

|---|---|

| [15] | Key prerequisites and ingredients of effective crisis management strategies. |

| [26] | A strategic and holistic framework with a component of flexibility, evaluation and strategy modification when necessary. |

| [62] | Risk amplification and stigmatization. |

| [57] | Dynamic roles of various stakeholders (emergency organizations, tourism organizations and tourism businesses) throughout all phases of a natural disaster crisis event. |

| [59] | Component of knowledge management strategy and feedback loop. |

| [30] | The coupling of actors and destination impacts to each crisis phase. |

| [44] | Integration of knowledge management by incorporating the use of GIS. |

| [55] | Collaborative approaches to build resilience of entire destinations and tourism businesses within. |

| [48] | Crisis assessment; safety of employees, customers and property ensured; self-saving and business activation and revitalization. |

| [46] | The role of vulnerability and resilience in driving the adaptive capacity of post-conflict destinations to adopt a transitory ‘Phoenix’ phase of initial recovery. |

| [58] | GPS strategy by taking agile, adaptive, resilient and innovative measures. |

| [47] | Influential antecedents shape responsive and reactive operational measures from owners-managers in response to the on-going COVID-19 pandemic to ensure business continuity. |

| [61] | Crisis-coping and post-recovery strategies amongst small and medium-sized hospitality and tourism firms. |

| [56] | Resilience as a dynamic and cyclical process, linked to each crisis management stage through three steps of dynamic capabilities. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Casal-Ribeiro, M.; Boavida-Portugal, I.; Peres, R.; Seabra, C. Review of Crisis Management Frameworks in Tourism and Hospitality: A Meta-Analysis Approach. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12047. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151512047

Casal-Ribeiro M, Boavida-Portugal I, Peres R, Seabra C. Review of Crisis Management Frameworks in Tourism and Hospitality: A Meta-Analysis Approach. Sustainability. 2023; 15(15):12047. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151512047

Chicago/Turabian StyleCasal-Ribeiro, Mariana, Inês Boavida-Portugal, Rita Peres, and Cláudia Seabra. 2023. "Review of Crisis Management Frameworks in Tourism and Hospitality: A Meta-Analysis Approach" Sustainability 15, no. 15: 12047. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151512047

APA StyleCasal-Ribeiro, M., Boavida-Portugal, I., Peres, R., & Seabra, C. (2023). Review of Crisis Management Frameworks in Tourism and Hospitality: A Meta-Analysis Approach. Sustainability, 15(15), 12047. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151512047