Assessment of Socioeconomic Resilience to Pandemic Disasters in Island Tourist Destinations

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

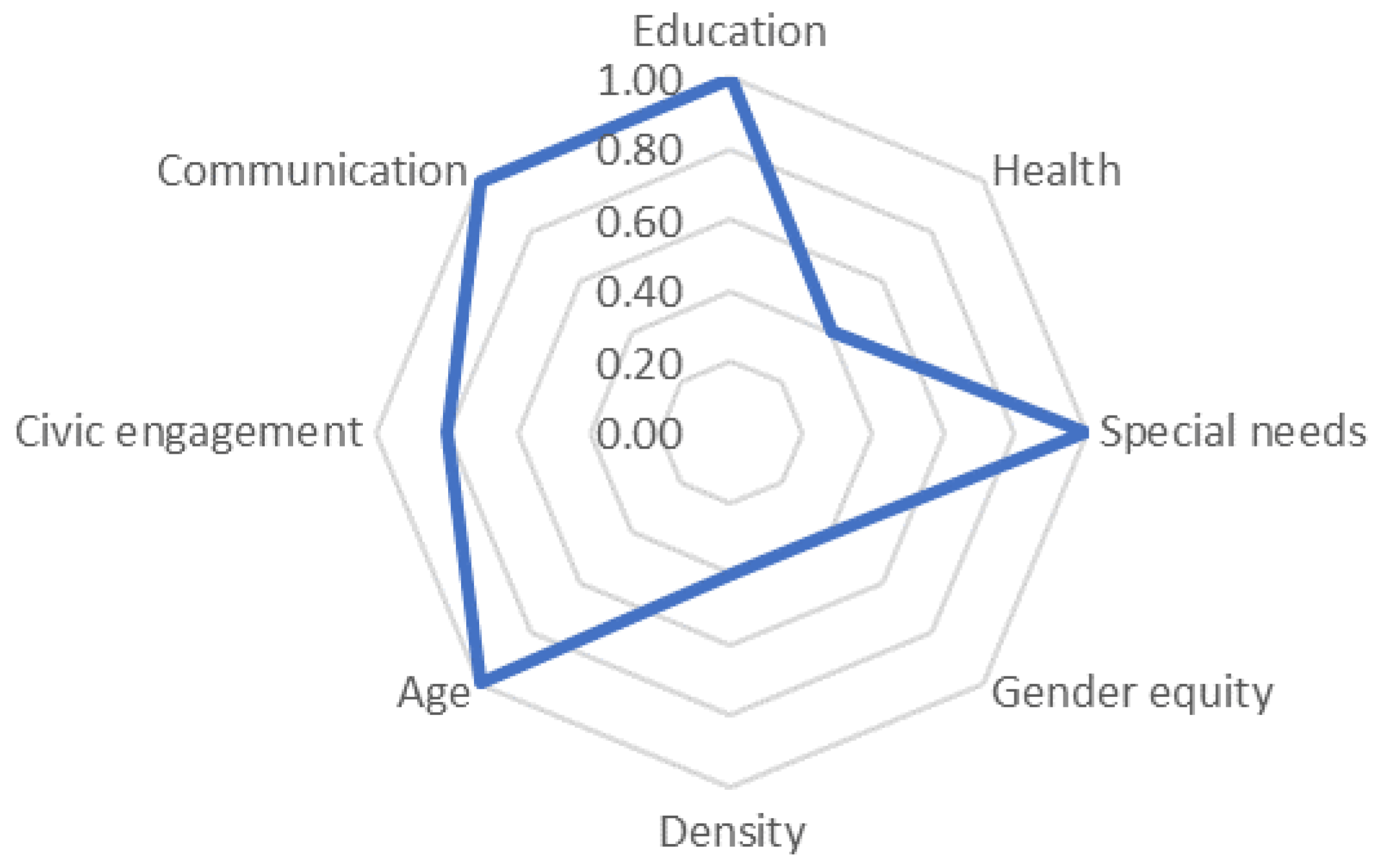

3.1. Social Dimension Results

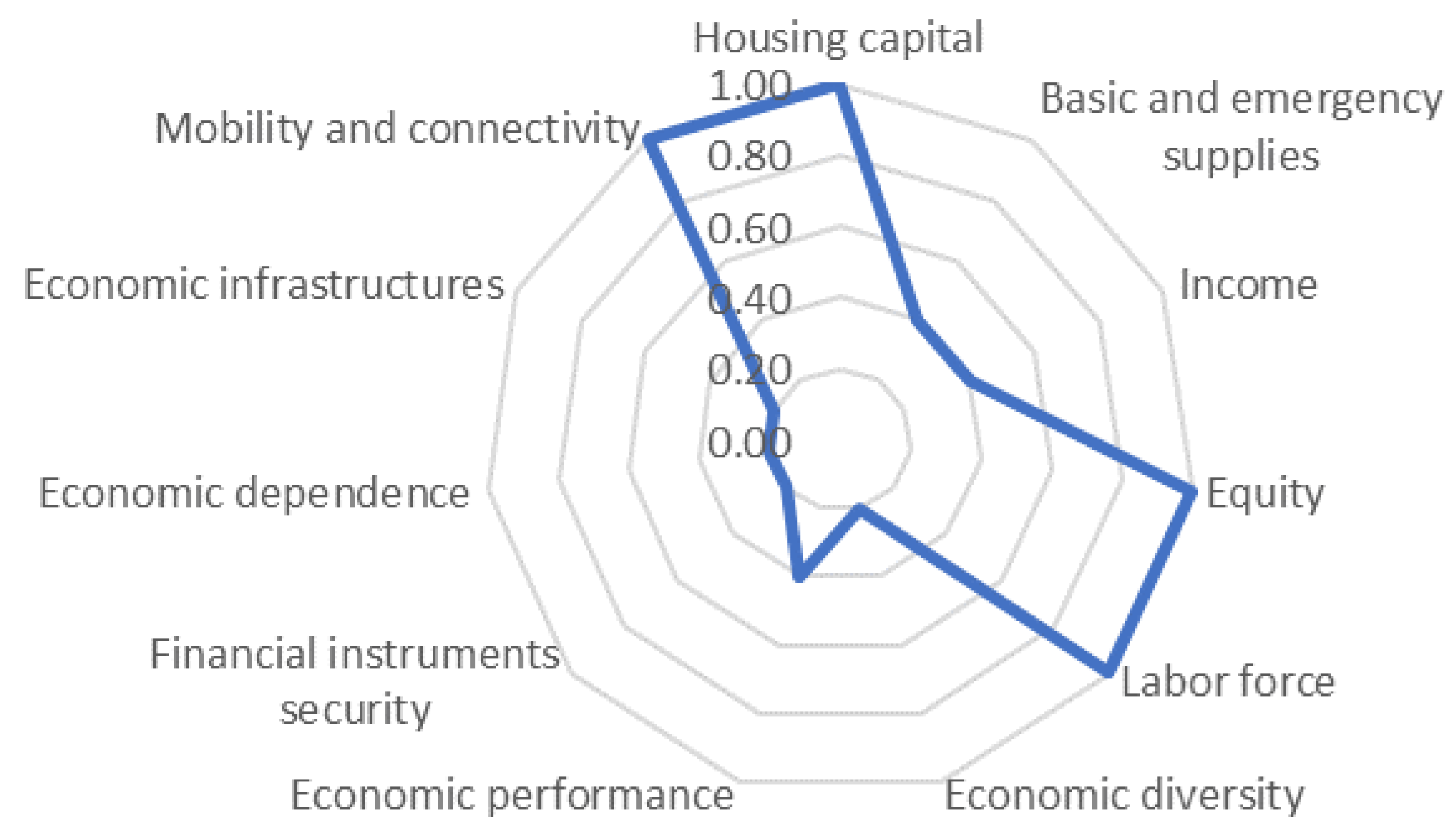

3.2. Economic Dimension Results

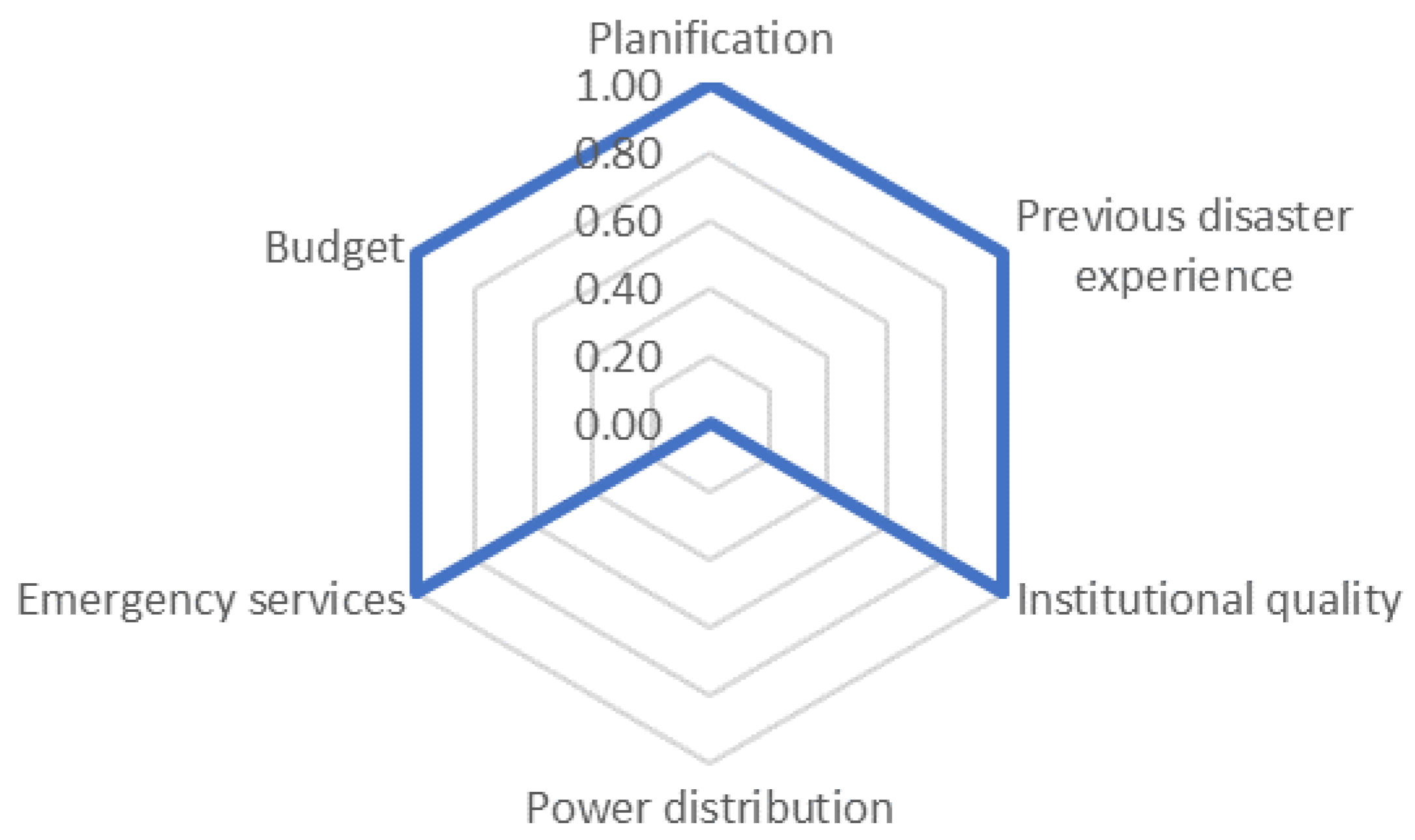

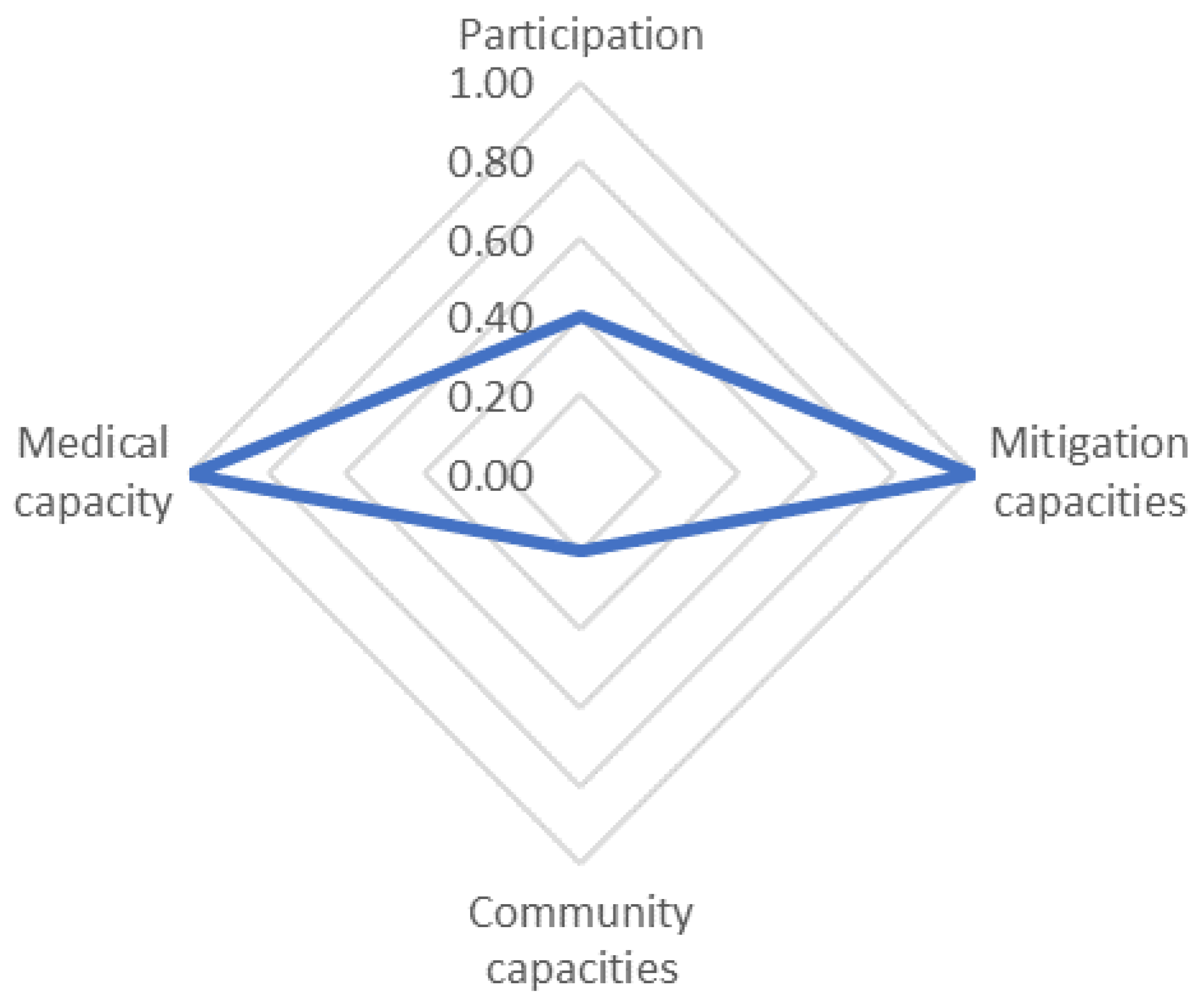

3.3. Institutional Dimension Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Indicators Frequency Analysis Table

| Indicator | Frequency Document | |

| Social dimension | Education | 47.62% |

| Health | 30.16% | |

| Special needs | 20.63% | |

| Gender equity | 14.29% | |

| Density | 30.16% | |

| Age | 41.27% | |

| Civic engagement | 14.29% | |

| Communication | 34.92% | |

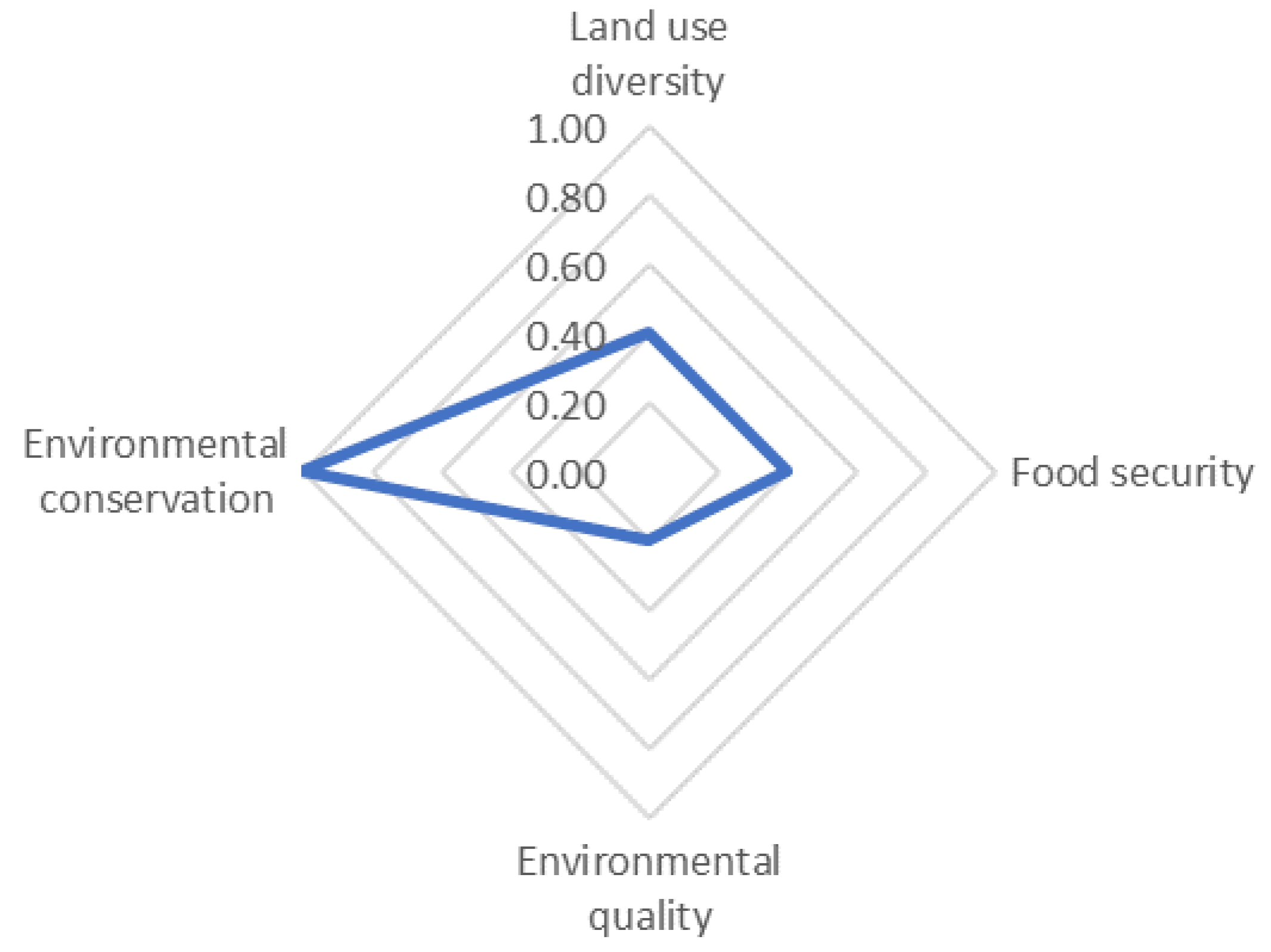

| Land use diversity | 26.98% | |

| Food security | 12.70% | |

| Environmental Quality | 14.29% | |

| Environmental conservation | 9.52% | |

| Economic dimension | Housing capital | 30.16% |

| Basic and emergency supplies | 33.33% | |

| Income | 38.10% | |

| Equity | 19.05% | |

| Labor force | 52.38% | |

| Economic diversity | 17.46% | |

| Economic performance | 30.16% | |

| Financial instruments security | 9.52% | |

| Economic dependence | 4.76% | |

| Economic infrastructures | 9.52% | |

| Mobility and connectivity | 33.33% | |

| Political dimension | Planification | 14.29% |

| Previous disaster experience | 7.94% | |

| Institutional quality | 19.05% | |

| Power distribution | 9.52% | |

| Emergency services | 22.22% | |

| Budget | 19.05% | |

| Participation | 9.52% | |

| Mitigation capacities | 17.46% | |

| Community capacities | 11.11% |

References

- Gaillard, J.-C.; Maceda, E.; Stasiak, E.; Masson, L.; Berre, L.; Espaldon, M. Vulnérabilité face aux aléas naturels littoraux et accès aux ressources: Perspectives philippines. In Proceedings of the International Pluridisciplinary Conference ‘The Littoral: Challenge, Dialogue, Action, Lille, France, 16–18 January 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kammouh, O.; Noori, A.Z.; Taurino, V.; Mahin, S.A.; Cimellaro, G.P. Deterministic and fuzzy-based methods to evaluate community resilience. Earthq. Eng. Eng. Vib. 2018, 17, 261–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, N. Urbanisation et Agriculture Intensive Augmentent le Risque de Pandémies. Available online: https://www.futura-sciences.com/sante/actualites/coronavirus-urbanisation-agriculture-intensive-augmentent-risque-pandemies-80160/ (accessed on 1 May 2021).

- Kern, J. La Destruction des Habitats Naturels Favorise L’émergence de Nouvelles Épidémies Comme le COVID-19. Available online: https://www.futura-sciences.com/sante/actualites/coronavirus-urbanisation-agriculture-intensive-augmentent-risque-pandemies-80160/ (accessed on 1 May 2021).

- Bates, A.E.; Mangubhai, S.; Milanés, C.B.; Rodgers, K.U.; Vergara, V. The COVID-19 pandemic as a pivot point for biological conservation. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 5176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bates, A.E.; Primack, R.B.; Biggar, B.S.; Bird, T.J.; Clinton, M.E.; Command, R.J.; Richards, C.; Shellard, M.; Geraldi, N.R.; Vergara, V.; et al. Global COVID-19 lockdown highlights humans as both threats and custodians of the environment. Biol. Conserv. 2021, 263, 109175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, J.K. Global Economic Effects of COVID-19; Congressional Research Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2021.

- Perillo, G.M.E.; Botero, C.M.; Milanes, C.B.; Elliff, C.I.; Cervantes, O.; Zielinski, S.; Bombana, B.; Glavovic, B.C. Integrated coastal zone management in the context of COVID-19. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2021, 210, 105687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IFRC. Drowning Just below the Surface: The Socioeconomic Consequences of the COVID-19 Pandemic; IFRC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Cepal, N. América Latina y el Caribe Ante la Pandemia del COVID-19: Efectos Económicos y Sociales; IFRC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins-Desbiolles, F. The “war over tourism”: Challenges to sustainable tourism in the tourism academy after COVID-19. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 29, 551–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foley, A.M.; Moncada, S.; Mycoo, M.; Nunn, P.; Tandrayen-Ragoobur, V.; Evans, C. Small Island Developing States in a post-pandemic world: Challenges and opportunities for climate action. WIREs Clim. Chang. 2022, 13, 769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Movono, A.; Scheyvens, R. Tourism and Politics: Responses to Crises in Island States. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2022, 19, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín, C.; Montañá, J.; Ramiréz-Rubio, O.; Ribes, M.; Chaccour, C. Como Responder a la Pandemia Desde un Estado Insular Pequeño? Available online: https://issuu.com/isglobal/docs/38_isglobal_covid-19_y_caribe_es (accessed on 12 November 2022).

- Briguglio, L. Small island developing states and their economic vulnerabilities. World Dev. 1995, 23, 1615–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McElroy, J.L. Tourism development in small islands across the world. Geogr. Ann. Ser. B Hum. Geogr. 2003, 85, 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmet, O.; Tahiroglu, M. Growth and equity in microstates. Int. J. Soc. Econ. 2002, 29, 152–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worrell, D. Development and Stabilization in Small Open Economies: Theories and Evidence from Caribbean Experience; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- CNET. Claves Para la Recuperación de la Industría Mexicana; CNET: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Damián, A.G. Vulnerabilidad cuando se depende del turismo: Covid-19 en Quintana Roo, México. Desarro. Econ. Soc. 2020, 9, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palafox-Muñoz, A.; Rubí-González, F. La gota que derramó el vaso en el turismo en Quintana Roo, México: Precariedad laboral y COVID-19. Dimens. Turísticas 2020, 4, 131–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Data Mexico. Cozumel Municipio de Quintana Roo. Available online: https://datamexico.org/es/profile/geo/cozumel (accessed on 11 May 2023).

- SEDETUR. Indicadores Turísticos Enero-Diciembre 2020; SEDETUR: Cancun, Mexico, 2020.

- Davila, F.; Bourke, R.M.; McWilliam, A.; Crimp, S.; Robins, L.; van Wensveen, M.; Alders, R.G.; Butler, J.R.A. COVID-19 and food systems in Pacific Island Countries, Papua New Guinea, and Timor-Leste: Opportunities for actions towards the sustainable development goals. Agric. Syst. 2021, 191, 103137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farrell, P.; Thow, A.M.; Wate, J.T.; Nonga, N.; Vatucawaqa, P.; Brewer, T.; Sharp, M.K.; Farmery, A.; Trevena, H.; Reeve, E.; et al. COVID-19 and Pacific food system resilience: Opportunities to build a robust response. Food Secur. 2020, 12, 783–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duro, J.A.; Perez-Laborda, A.; Turrion-Prats, J.; Fernández-Fernández, M. COVID-19 and tourism vulnerability. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2021, 38, 100819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milanes, C.B.; Pérez Montero, O.; Cabrera, J.A.; Cuker, B. Recommendations for coastal planning and beach management in Caribbean insular states during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2021, 208, 105575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melián-Alzola, L.; Fernández-Monroy, M.; Hidalgo-Peñate, M. Hotels in contexts of uncertainty: Measuring organisational resilience. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 36, 100747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruneckiene, J.; Pekarskiene, I.; Palekiene, O.; Simanaviciene, Z. An Assessment of Socio-Economic Systems’ Resilience to Economic Shocks: The Case of Lithuanian Regions. Sustainability 2019, 11, 566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallegatte, S.; Bangalore, M.; Vogt-Schilb, A.C. Socioeconomic resilience: Multi-hazard estimates in 117 countries. In World Bank Policy Research Working Paper; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Reghezza-Zitt, M. Utiliser la polysémie de la résilience pour comprendre les différentes approches du risque et leur possible articulation. EchoGéo 2013, 24, 13401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quenault, B. Retour critique sur la mobilisation du concept de résilience en lien avec l’adaptation des systèmes urbains au changement climatique. EchoGéo 2013, 24, 13403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wisner, B.; Gaillard, J.C.; Kelman, I. Framing disaster: Theories and stories seeking to understand Hazards, vulnerability and risk. In Handbook of Hazards and Disaster Risk Reduction; Routledge: London, UK, 2012; pp. 18–34. [Google Scholar]

- INEGI. México en Cifras. Cozumel, Quintana Roo (23001). In Indicadores. Grado Promedio de Escolaridad de la Población de 15 y más años (Años de Escolaridad), 2020; Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía: Aguascalientes, Mexico, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- CONEVAL. Medición de la Pobreza, Indice de Rezago Social (IRS), Anexos Estadísticos del IRS 2000–2020; Consejo Nacional de Evaluación de la Politíca de Desarrollo Social: Mexico City, Mexico, 2020.

- CONEVAL. Medición de la Pobreza, Pobrezaq por Grupos Poblacionales a Escala Municipal 2010, 2015 y 2020; Consejo Nacional de Evaluación de la Politíca de Desarrollo Social: Mexico City, Mexico, 2020.

- INEGI. Sistema de consulta. Banco de indicadores. Demografía y Sociedad. Población. In Densidad de Población (Habitantes por Kilómetro Cuadrado), Cozumel, 2020; Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía: Aguascalientes, Mexico, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- INEGI. Sistema de consulta. Banco de indicadores. Demografía y Sociedad. In Población. Relación de Dependencia (Porcentaje), Cozumel, 2020; Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía: Aguascalientes, Mexico, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- CONEVAL. Medición de la Pobreza, la Cohesión Social; Consejo Nacional de Evaluación de la Politíca de Desarrollo Social: Mexico City, Mexico, 2020.

- INEGI. Sistema de consulta. Banco de indicadores. Demografía y Sociedad. Hogares y Vivienda. Vivienda. In Porcentaje de Viviendas Particulares Habitadas que Disponen de Internet (Porcentaje), Cozumel, 2020; Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía: Aguascalientes, Mexico, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- CONABIO. Geo Portal Conabio, Vegetación y Uso de Suelo (73), INEGI (7), Uso del Suelo y Vegetación, Escala 1:250000, Serie VI, Uso del Suelo y Vegetación, Escala 1:250000, Serie VII; Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad: Mexico City, Mexico, 2021.

- SIAP. Acciones y Programas Cierre de la Producción Agrícola; Servicio de Información Agroalimentaria y Pesquera: Mexico City, Mexico, 2021.

- CONABIO. Geo Portal Conabio, Biodiversidad (14993), Índice de Capital Natural (13), Índice de Sustentabilidad de Capital Natural (ISCN); Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad: Mexico City, Mexico, 2019.

- Gobierno de Quintana Roo. Impulso a la Conservación y Uso Sustentable de Recursos Naturales. Available online: https://qroo.gob.mx/sema/2023/04/18/impulso-a-la-conservacion-y-uso-sustentable-de-recursos-naturales/ (accessed on 9 April 2023).

- Hafsi, A.; Frausto-Martínez, O. Community resilience to hurricane disasters in urban coastal areas: Cozumel island, Mexico. In Vulnerabilidad, Resiliencia y Riesgos Emergentes en Época de Pandemia; Una Visión Desde REDESclim; Redesclim-Conacyt; González Sosa, E., Travieso Bello, A.C., Romo Aguilar, M.D.L., Welsh Rodríguez, C.M., Eds.; Universidad Autonoma de Queretaro: Queretaro, Mexico, 2022; pp. 43–63. [Google Scholar]

- CONEVAL. Buscador CONEVAL, Indicadores_Cohesion_Social_Municipio_Mexico_2010-2020; Consejo Nacional de Evaluación de la Politíca de Desarrollo Social: Mexico City, Mexico, 2020.

- INEGI. Sistema de consulta. Banco de indicadores. Demografía y Sociedad. Empleo y ocupación. In Porcentaje de la Población de 12 años y más Económicamente Activa Ocupada (Porcentaje), Cozumel, 2020; Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía: Aguascalientes, Mexico, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Frausto, M.O.; Tun Chim, J.; Colín Olivares, O.; Vázquez Sosa, A.; Dzul Pech, R.; Isla Garcia, R.; Hernández Aguilar, M.L.; Campos Vargas, M.; Arroyo Arcos, L.; Palacio Aponte, G. Perfil de resiliencia urbana de la isla de Cozumel, México. In Gestión de Información Sobre Riesgi Ante Desastres Hidrometeorológicos en México. Dossier 1; Antrópica Revista de Ciencias Sociales y Humanidades: Yucatan, Mexico, 2018; Volume 4. [Google Scholar]

- Turimexico. Terminales Marítimas y Aéreas en Cozumel. Available online: https://www.turimexico.com/ciudades-de-mexico/cozumel/terminales-maritimas-y-aereas-en-cozumel/ (accessed on 9 May 2023).

- SALUD. Plan Nacional Para la Preparación y Respuesta Ante la Intensificación de la Influenza Estacional o ante una Pandemia de Influenza; Secretaria de Salud: Mexico City, Mexico, 2018.

- Ayuntamiento de Cozumel. Atlas de Riesgos del Municipio de Cozumel; H. Ayuntamiento de Cozumel: San Miguel de Cozumel, Mexico, 2012.

- Frausto Martínez, O.; Chim, J.T.; Olivares, O.C.; Sosa, A.V.; Pech, R.D.; Garcia, R.I.; Aguilar, M.L.H.; Vargas, M.C.; Arcos, L.A.; Aponte, G.P. Perfil de resiliencia urbana de la isla de Cozumel, México. Antrópica. Rev. Cienc. Soc. Humanidades 2018, 4, 215–237. [Google Scholar]

- Ayuntamiento de Cozumel. Presupuesto de Egresos del Ejercicio Fiscal 2019; H. Ayuntamiento de Cozumel: San Miguel de Cozumel, Mexico, 2019.

- Ayuntamiento de Cozumel. Presupuesto de Egresos del Ejercicio Fiscal 2023. Available online: https://cozumel.gob.mx/prensa/cabildo-aprueba-por-unanimidad-presupuesto-de-egresos-del-ejercicio-fiscal-2023/#:~:text=Por%20unanimidad%20el%20Honorable%20Ayuntamiento,con%20el%20programa%20de%20ingresos (accessed on 12 May 2023).

- IEQROO. Estadística Electoral Participación Ciudadana y Resultados Electorales; Instituto Electoral de Quintana Roo: Chetumal, Mexico, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- IEQROO. Estadística Electoral y de Participación Ciudadana; Instituto Electoral de Quintana Roo: Chetumal, Mexico, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- UNDRR. Sendai Framework Terminology on Disaster Risk Reduction. Resilience. Available online: https://www.undrr.org/terminology/resilience (accessed on 28 May 2023).

- Cid Nacer, J.; Milanés Batista, C.; Pinto Osorio, D.; Núñez Alvarez, J. La Informática y la Gestión Integrada de los sistemas de alertas tempranas dentro del manejo integrado de zonas costeras. In Estudios de caso Sobre Manejo Integrado de Zonas Costeras en Iberoamérica; Editorial Educosta: Barranquilla, Colombia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hafsi, A.; Aguilar-Becerra, C.D.; Frausto, O.M. Sistemas de alerta temprana basado en la comunidad ante fenómenos hidrometeorológicos en localidades situadas en barras de litoral costera. In Sistemas de Alerta Temprana Ante Fenómenos Hidrometeorológicos Extremos en Mexico; Redesclim-conacyt; Martínez, O.F., Morales, J.C.H., Aguilar-Becerra, C.D., Eds.; Uagroo: Mexico City, Mexico, 2020; pp. 29–54. [Google Scholar]

- Basher, R. Global early warning systems for natural hazards: Systematic and people-centred. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2006, 364, 2167–2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelman, I.; Mercer, J.; Gaillard, J.-C. The Routledge Handbook of Disaster Risk Reduction Including Climate Change Adaptation; Routledge Londres: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sufri, S.; Dwirahmadi, F.; Phung, D.; Rutherford, S. A systematic review of community engagement (CE) in disaster early warning systems (EWSs). Prog. Disaster Sci. 2020, 5, 100058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Theoretical Indicators | Practical Indicators | Sources | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social dimension | Social resources | Education | The average level of schooling of the population 15 years of age and older (Years of education) | INEGI [34] |

| Health | Population not entitled to health services (In %) | CONEVAL [35] | ||

| Special needs | Social backwardness (Index) | CONEVAL [35] | ||

| Gender equity | Female population with income below the income poverty line (In %) | CONEVAL [36] | ||

| Density | Population density (Inhabitants per square kilometer) | INEGI [37] | ||

| Age | Dependency ratio of Cozumel (In %) | INEGI [38] | ||

| Civic engagement | Social Network Perception Index (Linker scale) | CONEVAL [39] | ||

| Communication | Percentage of inhabited private homes with Internet access (In %) | INEGI [40] | ||

| Natural resources | Land use diversity | The total area of agricultural land in the municipality (hectares) | CONABIO [41] | |

| Food security | Agricultural production (in thousands of pesos) | SIAP [42] | ||

| Environmental quality | Natural Capital Sustainability Index (NCSI) | CONABIO [43] | ||

| Environmental conservation | Existence of environmental conservation plans (Yes/No) | Gobierno de Quintana Roo [44] | ||

| Economic dimension | Economic Resources | Housing capital | Percentage of inhabited private housing owned (In %) | UQROO [45] |

| Basic and emergency supplies | Population lacking access to essential services in housing (In %) | CONEVAL [36] | ||

| Income | Population below the income poverty line by income (In %) | CONEVAL [36] | ||

| Equity | GINI Coefficient (Index) | CONEVAL [46] | ||

| Labor force | Percentage of the economically active male population aged 12 years and older in employment (Percentage) | INEGI [47] | ||

| Economic diversity | Number of active economic sectors | Data Mexico [22] | ||

| Economic performance | Profit reinvestment (In millions of USD) | Data Mexico [22] | ||

| Financial instruments security | Existence of a financial instrument security (Yes/No) | UQROO [48] | ||

| Economic dependence | The concentration of total income of the tertiary sector Cozumel (In %) | Data Mexico [22] | ||

| Physical infrastructure | Economic infrastructures | Number of economic units | Data Mexico [22] | |

| Mobility and connectivity | Number of access points | Turimexico [49] | ||

| Political dimension | Politicalresources | Planification | Existence of an action plan for pandemic events (Yes/No) | SALUD [50] |

| Earlier disaster experience | Existence of earlier pandemic disaster experience (Yes/No) | H. Ayuntamiento de Cozumel [51] | ||

| Institutional quality | Trust in authorities (In %) | Data Mexico [22] | ||

| Power distribution | Inclusive representation within the government | Nd | ||

| Emergency services | Sufficient emergency services (Yes/No) | UQROO [52] | ||

| Budget | The approved budget for the fiscal year (In millions of pesos) | H. Ayuntamiento de Cozumel [53,54] | ||

| Human resources | Participation | Citizen participation in municipal elections (%) | IEQROO [55,56] | |

| Mitigation abilities | Existence of pandemic risk sensibilization campaign (Yes/No) | UQROO [48] | ||

| Community abilities | Population member of a neighbor group support (In %) | UQROO [52] | ||

| Earlier disaster experience | Number of hospital beds for emergencies | UQROO [45] |

| Definition | Rating | Skills |

|---|---|---|

| Data were available for all periods and showed an improvement or a stabilization of the highest standard. | 1 | Knowledge, resistance, absorptive, adaptive, learning, and building back better abilities. |

| Data were available for all periods, showing a recovery ability to the first stage. | 0.8 | Knowledge, resistance, absorptive, adaptive abilities. |

| Data were not available before the disruptive event but were developed after the event. | 0.6 | Knowledge and learning abilities. |

| Data were available for all periods and show a regression. | 0.4 | Knowledge but decrease in abilities. |

| Data were available before the event but not after. | 0.2 | Lack of knowledge and decrease of abilities. |

| Data were not available. | 0 | Lack of knowledge. |

| Indicator | Practical Indicator | 2015–2019 | 2020–2023 | Sources | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social resources | Education | The average level of schooling of the population 15 years of age and older (Years of education) | 9.5 | 10.1 | [34] |

| Health | Population not entitled to health services (In %) | 15.55% | 21.75% | [35] | |

| Special needs | Social backwardness (Index) | −1.212684 | −1.133519 | [35] | |

| Gender equity | Female population with income below the income poverty line (In %) | 43.3% | 52.9% | [36] | |

| Density | Population density (Inhabitants per square kilometer) | 177.1 | 181.6 | [37] | |

| Age | Dependency ratio of Cozumel (In %) | 48.60% | 43% | [38] | |

| Civic engagement | Social Network Perception Index (Linker scale) | Medium | Medium | [39] | |

| Communication | Percentage of inhabited private homes with Internet access (In %) | 45.40% | 70.40% | [40] | |

| Natural resources | Land use diversity | The total area of agricultural land in the municipality (hectares) | 6.00 × 106 | 2.49 × 106 | [41] |

| Food security | Agricultural production (in thousands of pesos) | 35.28 | 0 | [42] | |

| Environmental quality | Natural Capital Sustainability Index (NCSI) | At Risk | Nd | [43] | |

| Environmental conservation | Existence of environmental conservation plans (Yes/No) | Yes | Yes | [44] |

| Indicator | Practical Indicator | 2015–2019 | 2020–2023 | Sources | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Economic resources | Housing capital | Percentage of inhabited private housing owned (In %) | 44% | 55.60% | [45] |

| Basic and emergency supplies | Population lacking access to essential services in housing (In %) | 3.6% | 3.2% | [36] | |

| Income | Population below the income poverty line by income (In %) | 41.8% | 51.6% | [36] | |

| Equity | GINI Coefficient (Index) | 0.363 | 0.381 | [46] | |

| Labor force | Percentage of the economically active male population aged 12 years and older in employment (Percentage) | 97.10% | 98.20% | [47] | |

| Economic diversity | Number of active economic sectors | 18 | Nd | [22] | |

| Economic performance | Profit reinvestment (In millions of USD) | 239 | 40 | [22] | |

| Financial instruments security | Existence of a financial instrument security (Yes/No) | No | Nd | [48] | |

| Economic dependence | The concentration of total income of the tertiary sector Cozumel (In %) | 96.2% | Nd | [22] | |

| Physical infrastructure | Economic infrastructures | Number of economic units | 4455 | Nd | [22] |

| Mobility and connectivity | Number of access points | 4 | 5 | [49] |

| Indicator | Practical Indicator | 2015–2019 | 2020–2023 | Sources | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Institutional resources | Planification | Existence of an action plan for pandemic events (Yes/No) | Yes | Yes | [50] |

| Previous disaster experience | Existence of previous pandemic disaster experience (Yes/No) | Yes | Yes | [51] | |

| Institutional quality | Trust in authorities (In %) | 50.1% | 55.7% | [22] | |

| Power distribution | Inclusive representation within the government | Nd | Nd | Nd | |

| Emergency services | Sufficient emergency services (Yes/No) | YES | YES | [52] | |

| Budget | The approved budget for the fiscal year (In millions of pesos) | 622 | 750 | [53,54] | |

| Human resources | Participation | Citizen participation in municipal elections (%) | 61% | 55% | [55,56] |

| Mitigation capacities | Existence of pandemic risk sensibilization campaign (Yes/No) | No | Yes | [48] | |

| Community capacities | Population member of a neighbor group support (In %) | 57.30% | Nd | [52] | |

| Medical capacity | Number of hospital beds for emergencies | 116 | 146 | [45] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hafsi, A.; Aguilar-Becerra, C.D.; Frausto-Martínez, O.; Rivas-Tapia, A.S. Assessment of Socioeconomic Resilience to Pandemic Disasters in Island Tourist Destinations. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11246. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151411246

Hafsi A, Aguilar-Becerra CD, Frausto-Martínez O, Rivas-Tapia AS. Assessment of Socioeconomic Resilience to Pandemic Disasters in Island Tourist Destinations. Sustainability. 2023; 15(14):11246. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151411246

Chicago/Turabian StyleHafsi, Adel, César Daniel Aguilar-Becerra, Oscar Frausto-Martínez, and Alejandra Sarhai Rivas-Tapia. 2023. "Assessment of Socioeconomic Resilience to Pandemic Disasters in Island Tourist Destinations" Sustainability 15, no. 14: 11246. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151411246

APA StyleHafsi, A., Aguilar-Becerra, C. D., Frausto-Martínez, O., & Rivas-Tapia, A. S. (2023). Assessment of Socioeconomic Resilience to Pandemic Disasters in Island Tourist Destinations. Sustainability, 15(14), 11246. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151411246