Relationship between Organizational Climate and Service Performance in South Korea and China

Abstract

1. Introduction

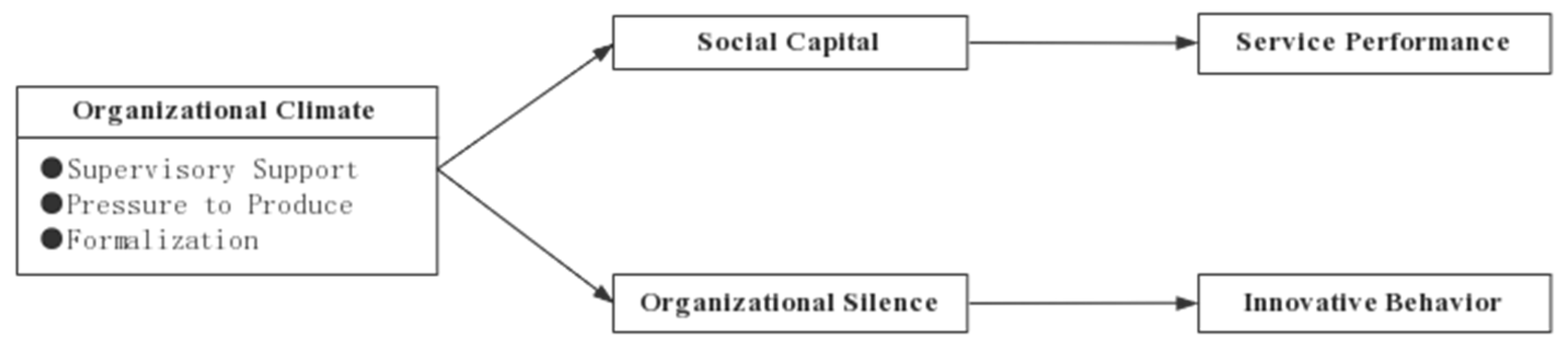

2. Theory and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Organizational Climate, Social Capital, and Organizational Silence

2.2. Social Capital, Organizational Silence, Service Performance, and Innovative Behavior

2.3. Social Capital and the Mediating Effects of Organizational Silence

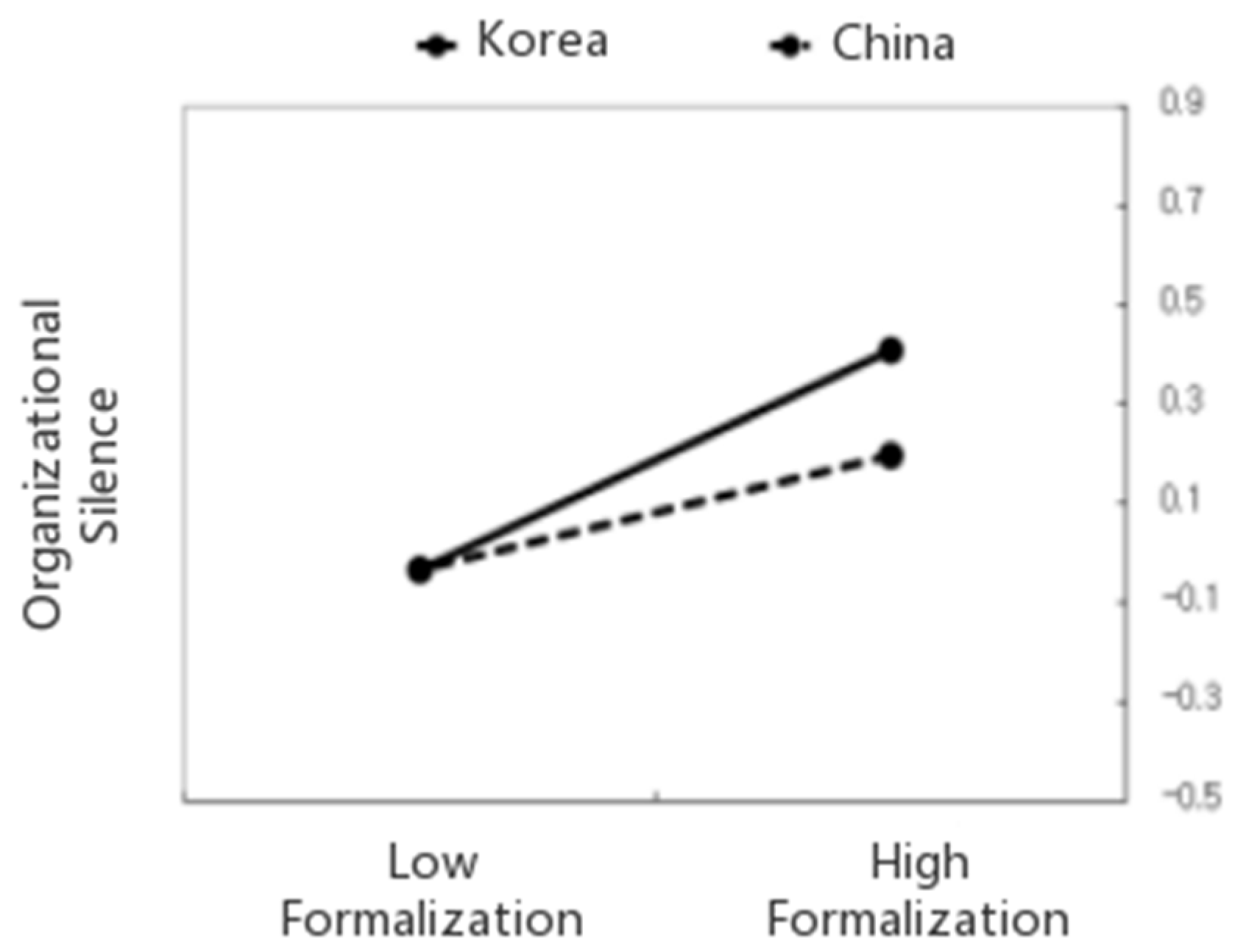

2.4. Comparison of Korea and China

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Collection

3.2. Measurement Tools

3.2.1. Organizational Climate

3.2.2. Social Capital and Organizational Silence

3.2.3. Innovative Behavior and Service Performance

4. Results

4.1. Sample Characteristics

4.2. Reliability and Validation

4.3. Correlation Analysis

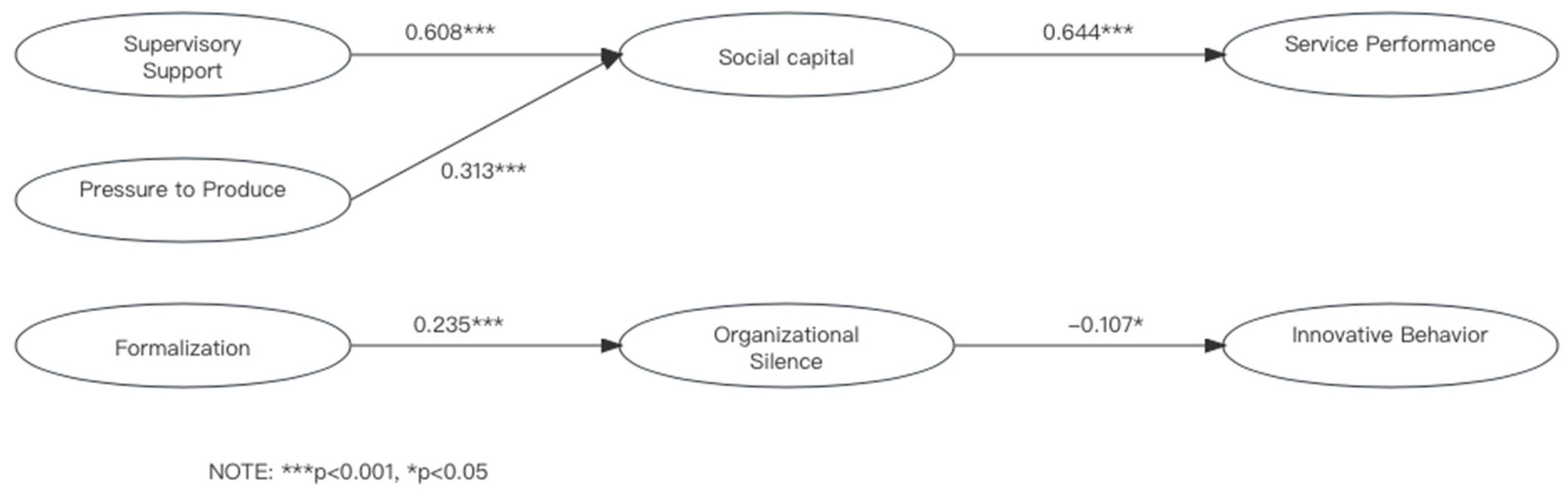

4.4. Hypothesis Testing

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lv, M.; Yang, S.; Lv, X.Y.; Zhang, L.; Chen, Z.Q.; Zhang, S.X. Organisational innovation climate and innovation behaviour among nurses in China: A mediation model of psychological empowerment. J. Nurs. Manag. 2021, 29, 2225–2233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dastmalchian, A.; Bacon, N.; McNeil, N.; Steinke, C.; Blyton, P.; Satish Kumar, M.; Varnali, R. High-performance work systems and organizational performance across societal cultures. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2020, 51, 353–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, D.E.; Waldman, D.A. Customer-driven employee performance. In The Changing Nature of Performance; Pulakos, Ed.; Jossey-Bass Inc.: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1999; Volume 154, p. 191. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, J.P.; McCloy, R.A.; Oppler, S.H.; Sager, C.E. A theory of performance. Pers. Sel. Organ. 1993, 3570, 35–70. [Google Scholar]

- West, M.A.; Farr, J.L. Innovation at work: Psychological perspectives. Soc. Behav. 1989, 4, 15–30. [Google Scholar]

- West, M.A.; Farr, J.L. Innovation at Work; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- He, P.X.; Wu, T.J.; Zhao, H.D.; Yang, Y. How to motivate employees for sustained innovation behavior in job stressors? A cross-level analysis of organizational innovation climate. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, P.; Liu, L.; Tan, J. Influence of knowledge sharing, innovation passion and absorptive capacity on innovation behaviour in China. J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 2021, 34, 894–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosma, N.; Van Praag, M.; Thurik, R.; De Wit, G. The value of human and social capital investments for the business performance of startups. Small Bus. Econ. 2004, 23, 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, R. Social capital and public service performance: A review of the evidence. Public Policy Adm. 2012, 27, 49–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnihotri, R.; Mani, S.; Chaker, N.N.; Daugherty, P.J.; Kothandaraman, P. Drivers and performance implications of frontline employees’ social capital development and maintenance: The role of online social networks. Decis. Sci. 2022, 53, 181–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagheri, G.; Zarei, R.; Aeen, M.N. Organizational silence (basic concepts and its development factors). Ideal Type Manag. 2012, 1, 47–58. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, X.T.; Chung, Y.W. The mediating effect of perceived stress and moderating effect of trust for the relationship between employee silence and behavioral outcomes. Psychol. Rep. 2021, 124, 1715–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.C.; Shao, J.; Liu, N.T.; Du, Y.S. Reading the wind: Impacts of leader negative emotional expression on employee silence. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 762920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whiten, A.; Biro, D.; Bredeche, N.; Garland, E.C.; Kirby, S. The emergence of collective knowledge and cumulative culture in animals, humans and machines. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 2022, 377, 20200306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauß, P.; Greven, A.; Brettel, M. Determining the influence of national culture: Insights into entrepreneurs’ collective identity and effectuation. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2021, 17, 981–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Hong, Y.Y.; Sanchez-Burks, J. Emotional aperture across east and west: How culture shapes the perception of collective affect. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2019, 50, 751–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, P. Power and Exchange in Social Life; John Wiley & Son: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Cropanzano, R.; Byrne, Z.S.; Bobocel, D.R.; Rupp, D.E. Moral Virtues, Fairness Heuristics, Social Entities, and Other Denizens of Organizational Justice. J. Vocat. Behav. 2001, 58, 164–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, G.S. A theory of social interaction. J. Political Econ. 1974, 82, 1063–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, B.; Reichers, A.E. On the etiology of climates. Pers. Psychol. 1983, 36, 19–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, L.R.; Sells, S.B. Psychological climate: Theoretical perspectives and empirical research. In Toward a Psychology of Situations: An Interactional Perspective; Magnusson, D., Ed.; Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1981; pp. 275–295. [Google Scholar]

- Rahmat, A.; Abdillah, M.R.; Priadana, M.S.; Wu, W.; Usman, B. Organizational Climate and Performance: The Mediation Roles of Cohesiveness and Organizational Commitment. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2020; Volume 469, p. 012048. [Google Scholar]

- Quinn, R.E.; Rohrbaugh, J. A spatial model of effectiveness criteria: Towards a competing values approach to organizational analysis. Manag. Sci. 1983, 29, 363–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, R.E.; McGrath, M.R. The Transformation of Organizational Cultures: A Competing Values Perspective; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Gifford, B.D.; Zammuto, R.F.; Goodman, E.A.; Hill, K.S. The relationship between hospital unit culture and nurses’ quality of work life/practitioner application. J. Healthc. Manag. 2002, 47, 13. [Google Scholar]

- Villeneuve, P.; Love, A.R.; Aerts, P.M.; Forero, J. Dimensions of Curation Competing Values Exhibition Model: Toward Intentional Curation. Int. J. Incl. Mus. 2021, 14, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu Tayeh, S.N.; Mustafa, M.H. Applying competing values framework to Jordanian hotels. Anatolia 2022, 33, 374–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emery, F.E.; Trist, E.L. The causal texture of organizational environments. Hum. Relat. 1965, 18, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGregor, D. Theory X and theory Y. Organ. Theory 1960, 358, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, S. Cultural studies: Two paradigms. Media Cult. Soc. 1980, 2, 57–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clinebell, S. Organizational effectiveness: An examination of recent empirical studies and the development of a contingency view. In Proceedings of the 27th Annual Conference of the Midwest Academy of Management; Terpening, W.D., Thompson, K.R., Eds.; Department of Management, University of Notre Dame: Sydney, NSW, Australia, 1984; pp. 92–102. [Google Scholar]

- Hutahayan, B. The mediating role of human capital and management accounting information system in the relationship between innovation strategy and internal process performance and the impact on corporate financial performance. Benchmarking Int. J. 2020, 27, 1289–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasurdin, A.M.; Ling, T.C.; Khan, S.N. Linking social support, work engagement and job performance in nursing. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2018, 19, 363–386. [Google Scholar]

- Setiabudhi, S.; Hadi, C.; Handoyo, S. Relationship Between Social Support, Affective Commitment, and Employee Engagement. Kontigensi J. Ilm. Manaj. 2021, 9, 690–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. Towards a model of work engagement. Career Dev. Int. 2008, 13, 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B.; Van Rhenen, W. How changes in job demands and resources predict burnout, work engagement, and sickness absenteeism. J. Organ. Behav. Int. J. Ind. Occup. Organ. Psychol. Behav. 2009, 30, 893–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, D.M.; Sun, N.; Hong, S.; Fan, Y.Y.; Kong, F.Y.; Li, Q.J. Occupational stress and coping strategies among emergency department nurses of China. Arch. Ves Psychiatr. Nurs. 2015, 29, 208–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Li, Z.; Wan, Q. Effects of work practice environment, work engagement and work pressure on turnover intention among community health nurses: Mediated moderation model. J. Adv. Nurs. 2019, 75, 3485–3494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellinger, A.E.; Musgrove, C.C.F.; Ellinger, A.D.; Bachrach, D.G.; Baş, A.B.E.; Wang, Y.L. Influences of organizational investments in social capital on service employee commitment and performance. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 1124–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, M.G.; West, M.A.; Shackleton, V.J.; Dawson, J.F.; Lawthom, R.; Maitlis, S.; Wallace, A.M. Validating the organizational climate measure: Links to managerial practices, productivity and innovation. J. Organ. Behav. 2005, 26, 379–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, R.; Ferreira, M.C.; Van Meurs, N.; Gok, K.; Jiang, D.Y.; Fontaine, J.R.; Abubakar, A. Does organizational formalization facilitate voice and helping organizational citizenship behaviors? It depends on (national) uncertainty norms. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2019, 50, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akintimehin, O.O.; Eniola, A.A.; Alabi, O.J.; Eluyela, D.F.; Okere, W.; Ozordi, E. Social capital and its effect on business performance in the Nigeria informal sector. Heliyon 2019, 5, e02024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanson, E.; Kim, S.; Lee, S.M.; Yang, J.J.; Lee, Y.K. The effect of leader competencies on knowledge sharing and job performance: Social capital theory. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 42, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troise, C.; Tani, M.; Jones, P. Investigating the impact of multidimensional social capital on equity crowdfunding performance. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 55, 102230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, P.S.; Kwon, S.W. Social capital: Prospects for a new concept. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2002, 27, 17–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurer, I.; Ebers, M. Dynamics of social capital and their performance implications: Lessons from biotechnology start-ups. Adm. Sci. Q. 2006, 51, 262–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayamajhee, V.; Bohara, A.K. Social capital, trust, and collective action in post-earthquake Nepal. Nat. Hazards 2021, 105, 1491–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gencer, G.; Atay, H.; Gurdogan, A.; Colakoglu, U. The relationship between organizational culture, organizational silence and job performance in hotels: The case of Kuşadasi. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2023, 6, 70–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audia, P.G.; Locke, E.A. Benefiting from negative feedback. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2003, 13, 631–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rösler, I.K.; van Nunspeet, F.; Ellemers, N. Falling on deaf ears: The effects of sender identity and feedback dimension on how people process and respond to negative feedback—An ERP study. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2023, 104, 104419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.P.; Leigh, T.W. A new look at psychological climate and its relationship to job involvement, effort, and performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 1996, 81, 358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabrera, E.F.; Cabrera, A. Fostering knowledge sharing through people management practices. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2005, 16, 720–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, S.; Han, Z.; Huo, B. Relational enablers of information sharing: Evidence from Chinese food supply chains. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2017, 117, 838–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Ma, Z.; Yu, H.; Jia, M.; Liao, G. Transformational leadership and employee knowledge sharing: Explore the mediating roles of psychological safety and team efficacy. J. Knowl. Manag. 2020, 24, 150–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wollack, S.; Goodale, J.G.; Wijting, J.P.; Smith, P.C. Development of the survey of work values. J. Appl. Psychol. 1971, 55, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatley, J. Intrinsic value and educational value. J. Philos. Educ. 2021, 55, 675–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, R. What if employees with intrinsic work values are given autonomy in worker co-operatives? Integration of the job demands–resources model and supplies–values fit theory. Pers. Rev. 2022, 52, 724–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-C.; Kim, J.-R. A study on the Cultural Characteristics and Job Values of Corporate Members in Korea and China. J. Tour. Ind. Res. 1996, 10, 233–260. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, H.; Zhang, Q.; Zheng, Y. Impact of work values and knowledge sharing on creative performance. Chin. Manag. Stud. 2021, 15, 86–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bang, J. A comparative study of Korean and Chinese labor values. Ph.D. Thesis, Chungnam National University, Daejeon, Republic of Korea, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Z.; Yang, F.; Boezeman, E.J.; Li, X. Do new-generation construction professionals be provided what they desire at work? A study on work values and supplies–values fit. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2020, 27, 2835–2858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. Culture and organizations. Int. Stud. Manag. Organ. 1980, 10, 15–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. Cultural constraints in management theories. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 1993, 7, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, M.; West, M.; Shackleton, V.; Lawthom, R.; Maitlis, S.; Robinson, D.; Dawson, J.; Wallace, A. Development and validation of an organizational climate measure. J. Organ. Behav. 2011, 26, 1–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahapiet, J.; Ghoshal, S. Social capital, intellectual capital, and the organizational advantage. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1998, 23, 242–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyne, L.V.; Ang, S.; Botero, I.C. Conceptualizing employee silence and employee voice as multidimensional constructs. J. Manag. Stud. 2003, 40, 1359–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, S.G.; Bruce, R.A. Determinants of innovative behavior: A path model of individual innovation in the workplace. Acad. Manag. J. 1994, 37, 580–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, H.; Chuang, A. A multilevel investigation of factors influencing employee service performance and customer outcomes. Acad. Manag. J. 2004, 47, 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harman, H.H. Modern Factor Analysis; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Su, F.; Cheng, D.; Wen, S. Multilevel impacts of transformational leadership on service quality: Evidence from China. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.-L. Development, measurement, and managerial implications of Chinese values. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2019, 5, 1615767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, D.S.; Gold, J.; Kim, J.; Kim, I. Social capital and career growth. Int. J. Manpow. 2019, 41, 100–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.H. Rambling with Zhuangzi: Imagination and spontaneity for public administration and governance. Adm. Theory Prax. 2006, 28, 275–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, W.H.; Warner, M. Strategic human resource management in western multinationals in China: The differentiation of practices across different ownership forms. Pers. Rev. 2002, 31, 553–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeffer, J. The Human Equation: Building Profits by Putting People First; Harvard Business Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Ceric, A.; Small, F.; Morrison, M. What Indigenous employees value in a business training programme: Implications for training design and government policies. J. Vocat. Educ. Train. 2022, 74, 228–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.Y.; Roh, T. Open for Green Innovation: From the Perspective of Green Process and Green Consumer Innovation. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magill, M.S.; Yost, P.R.; Chighizola, B.; Stark, A. Organizational climate for climate sustainability. Consult. Psychol. J. Pract. Res. 2020, 72, 198–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çaylak, E.; Altuntas, S. Organizational silence among nurses: The impact on organizational cynicism and intention to leave work. J. Nurs. Res. 2017, 25, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal, A.; Griffin, M.A.; Hart, P.M. The impact of organizational climate on safety climate and individual behavior. Saf. Sci. 2000, 34, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, L.; Xu, S.; Liu, X.; Chen, W. A meta-analytic review of the consequences of servant leadership: The moderating roles of cultural factors. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2021, 38, 371–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.-J.; Roh, T. Digitalization capability and sustainable performance in emerging markets: Mediating roles of in/out-bound open innovation and coopetition strategy. Manag. Decis. 2023. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographic Variable | Type | Korea | China |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 130 | 180 |

| Female | 150 | 313 | |

| Age | Younger than 25 years | 49 | 224 |

| 26–30 years old | 78 | 95 | |

| 31–35 years old | 69 | 79 | |

| 36–40 years old | 39 | 60 | |

| 41–50 years old | 31 | 25 | |

| Older than 50 years | 14 | 10 | |

| Educational Background | High school degree or below | 15 | 15 |

| College degree | 84 | 299 | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 161 | 141 | |

| Master’s degree | 16 | 26 | |

| PhD degree or above | 4 | 12 | |

| Tenure | Work for 0–5 years | 121 | 285 |

| Work for 6–10 years | 71 | 103 | |

| Work for 11–15 years | 39 | 67 | |

| Work for 16–20 years | 29 | 17 | |

| Over 20 years of work | 20 | 21 | |

| Position | Contract Workers | 39 | 254 |

| Staff | 111 | 93 | |

| Assistant Manager | 73 | 86 | |

| General Manager | 38 | 43 | |

| Department Manager | 12 | 17 | |

| Executive | 4 | 0 | |

| Other | 3 | 0 | |

| Type of Job | Planning/Advertising | 111 | 181 |

| Sales/Marketing | 77 | 170 | |

| Management/Office | 91 | 134 | |

| Other | 1 | 0 | |

| Organizational Size | Fewer than 50 people | 15 | 145 |

| 51–100 people | 52 | 74 | |

| 101–200 people | 36 | 77 | |

| 201–500 people | 75 | 73 | |

| More than 500 people | 102 | 124 | |

| Total | 280 | 493 | |

| Variables | Items | Factor Loading | Cronbach’s α | CR | AVE | Model Fit | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Korea | China | Korea | China | Korea | China | Korea | China | |||

| Supervisory Support | ss1 | 0.759 | 0.745 | 0.880 | 0.849 | 0.916 | 0.884 | 0.732 | 0.656 | χ2 = 3721.261 df = 1617 p = 0.000 CFI = 0.930 GFI = 0.880 AGFI = 0.860 NFI = 0.884 RMR = 0.030 RMSEA = 0.029 |

| ss2 | 0.835 | 0.775 | ||||||||

| ss3 | 0.861 | 0.767 | ||||||||

| ss4 | 0.765 | 0.770 | ||||||||

| Formalization | f1 | 0.783 | 0.782 | 0.809 | 0.791 | 0.864 | 0.848 | 0.680 | 0.651 | |

| f2 | 0.781 | 0.754 | ||||||||

| f3 | 0.737 | 0.710 | ||||||||

| Pressure to Produce | ptp1 | 0.842 | 0.706 | 0.853 | 0.782 | 0.889 | 0.840 | 0.729 | 0.636 | |

| ptp2 | 0.864 | 0.752 | ||||||||

| ptp3 | 0.739 | 0.754 | ||||||||

| Organizational Silence | as1 | 0.792 | 0.795 | 0.933 | 0.908 | 0.940 | 0.871 | 0.690 | 0.500 | |

| as2 | 0.827 | 0.851 | ||||||||

| as3 | 0.829 | 0.837 | ||||||||

| as4 | 0.861 | 0.816 | ||||||||

| ds1 | 0.825 | 0.727 | ||||||||

| ds2 | 0.773 | 0.683 | ||||||||

| ds3 | 0.810 | 0.659 | ||||||||

| Social Capital | sc1 | 0.706 | 0.626 | 0.915 | 0.881 | 0.944 | 0.907 | 0.650 | 0.521 | |

| sc2 | 0.699 | 0.628 | ||||||||

| sc3 | 0.754 | 0.586 | ||||||||

| rc1 | 0.713 | 0.702 | ||||||||

| rc2 | 0.812 | 0.752 | ||||||||

| rc3 | 0.738 | 0.671 | ||||||||

| cc1 | 0.723 | 0.666 | ||||||||

| cc2 | 0.742 | 0.728 | ||||||||

| cc3 | 0.756 | 0.688 | ||||||||

| Innovative Behavior | ib1 | 0.783 | 0.710 | 0.838 | 0.751 | 0.871 | 0.814 | 0.692 | 0.593 | |

| ib2 | 0.818 | 0.694 | ||||||||

| ib3 | 0.788 | 0.717 | ||||||||

| Service Performance | sp1 | 0.768 | 0.724 | 0.889 | 0.855 | 0.935 | 0.906 | 0.707 | 0.616 | |

| sp2 | 0.793 | 0.657 | ||||||||

| sp3 | 0.794 | 0.693 | ||||||||

| sp4 | 0.715 | 0.713 | ||||||||

| sp5 | 0.755 | 0.704 | ||||||||

| sp6 | 0.699 | 0.734 | ||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Korea | 1. Supervisory Support | 1 | ||||||

| 2. Formalization | −0.481 ** | 1 | ||||||

| 3. Pressure to Produce | 0.570 ** | −0.653 ** | 1 | |||||

| 4. Organizational Silence | −0.351 ** | 0.331 ** | −0.382 ** | 1 | ||||

| 5. Social Capital | 0.705 ** | −0.536 ** | 0.556 ** | −0.332 ** | 1 | |||

| 6. Innovative Behavior | 0.532 ** | −0.453 ** | 0.567 ** | −0.257 ** | 0.556 ** | 1 | ||

| 7. Service Performance | 0.501 ** | −0.677 ** | 0.556 ** | −0.356 ** | 0.553 ** | 0.468 ** | 1 | |

| China | 1. Supervisory Support | 1 | ||||||

| 2. Formalization | −0.487 ** | 1 | ||||||

| 3. Pressure to Produce | 0.473 ** | −0.655 ** | 1 | |||||

| 4. Organizational Silence | −0.165 ** | 0.131 ** | −0.096 ** | 1 | ||||

| 5. Social Capital | 0.674 ** | −0.501 ** | 0.539 ** | −0.157 ** | 1 | |||

| 6. Innovative Behavior | 0.468 ** | −0.541 ** | 0.650 ** | −00.038 | 0.532 ** | 1 | ||

| 7. Service Performance | 0.435 ** | −0.668 ** | 0.641 ** | −0.129 ** | 0.525 ** | 0.566 ** | 1 | |

| Independent Variable | Parameters | Dependent Variable | Total | Korea | China |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Supervisory Support | Social capital | Service Performance | 0.293 ** | 0.317 ** | 0.283 ** |

| Pressure to Produce | Social capital | Service Performance | 0.143 ** | 0.127 ** | 0.149 ** |

| Formalization | Organizational Silence | Innovative Behavior | −0.015 * | −0.085 ** | −0.005 |

| Korea | China | t-Value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | p | β | p | ||||

| Social Capital | ← | Supervisory Support | 0.630 | *** | 0.596 | *** | −0.843 |

| Social Capital | ← | Pressure to Produce | 0.248 | *** | 0.346 | *** | 1.84 |

| Organizational Silence | ← | Formalization | 0.436 | *** | 0.166 | *** | −2.123 * |

| Innovative Behavior | ← | Organizational Silence | −0.303 | *** | −0.052 | 0.34 | 3.625 ** |

| Service Performance | ← | Social Capital | 0.641 | *** | 0.651 | *** | 0.401 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Quan, X.; Choi, M.-C.; Tan, X. Relationship between Organizational Climate and Service Performance in South Korea and China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10784. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151410784

Quan X, Choi M-C, Tan X. Relationship between Organizational Climate and Service Performance in South Korea and China. Sustainability. 2023; 15(14):10784. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151410784

Chicago/Turabian StyleQuan, Xuezhe, Myeong-Cheol Choi, and Xiao Tan. 2023. "Relationship between Organizational Climate and Service Performance in South Korea and China" Sustainability 15, no. 14: 10784. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151410784

APA StyleQuan, X., Choi, M.-C., & Tan, X. (2023). Relationship between Organizational Climate and Service Performance in South Korea and China. Sustainability, 15(14), 10784. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151410784