Authorization or Outsourcing: Considering the Contrast/Assimilation Effect and Network Externality of Remanufactured Products under Government Subsidy

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Questions

- (1)

- Which remanufacturing mode is optimal for the OEM/TPR/CLSC considering the contrast/assimilation effect and the network externality of remanufactured products under government subsidy?

- (2)

- Which remanufacturing mode is better from the perspective of the environment and society?

- (3)

- How do the contrast/assimilation effect, network externality and government subsidy affect OEMs’ remanufacturing mode selection and the operations of the CLSC?

1.2. Flow of Study

- (1)

- We establish two remanufacturing models which provides managerial guidance for OEMs in regard to their remanufacturing mode-selection strategy.

- (2)

- We compare the optimal pricing decisions, demands and profits of the CLSC in two remanufacturing models.

- (3)

- We conduct numerical analysis to explore the impact of the OEM’s remanufacturing mode selection strategy on the environment, consumer surplus and social welfare.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Government Subsidy in CLSCs

2.2. Contrast/assimilation Effect in CLSCs

2.3. Network Externality in SCs

2.4. Remanufacturing Mode in CLSC

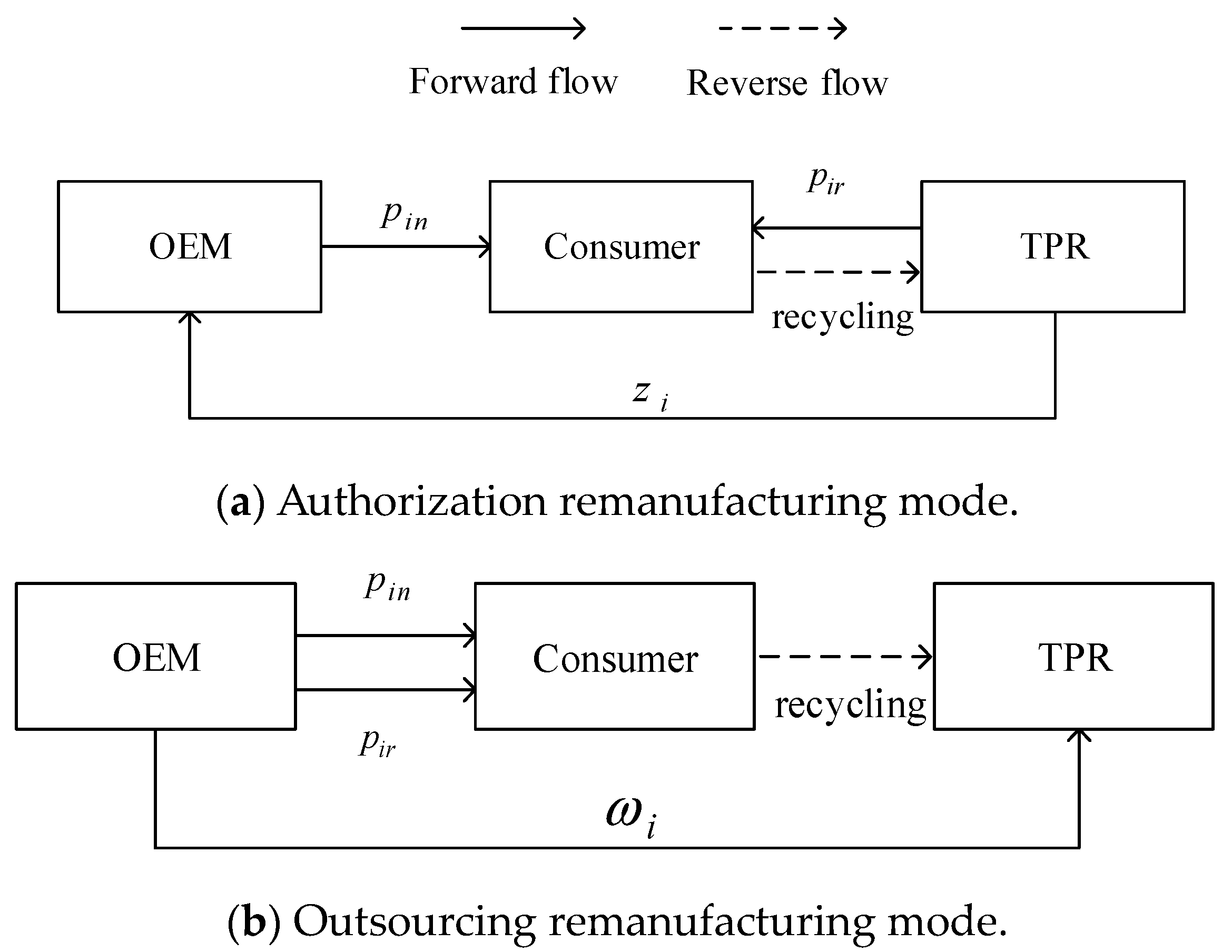

3. Model Overview

3.1. Problem Description

3.2. Notations

3.3. Assumptions

- (1)

- (2)

- The quantity of used products available for remanufacturing is sufficient; therefore, the decisions of the CLSC members are not restricted by the quantity of used products recycled [44];

- (3)

- Consumers’ willingness to pay for a new product is , which is a uniform distribution with the supporting range ;

- (4)

- Each consumer’s willingness to pay for the remanufactured product is a fraction of their willingness to pay for the new product, where .

- (5)

- Each consumer maximizes his net utility by purchasing at most one unit of the new or remanufactured product [43];

- (6)

- Consumers are myopic; they only focus on the utility of the current period and not on the utility of the next period when making a purchase decision [14];

- (7)

- Based on the work of Agrawal et al. [12], since the remanufactured products in Model O are sold to consumers by the OEM, from the consumers’ view, there is no difference between the remanufactured product in Model O and the remanufactured ones in the OEM self-remanufacturing mode; therefore, it is assumed that it also exists assimilation effect in Model O. For feasibility of the proposed models, we assume the contrast effect coefficient in Model A equals to the assimilation effect coefficient in Model O, i.e., . Then, in the second period, consumers’ willingness to pay for a new product in Model A and Model O can be written as and separately;

- (8)

- Compared to new products, consumers are more reluctant to purchase a remanufactured product since they are uncertain about the quality of remanufactured ones. Then, we assume that network externality only occurs among consumers who purchase the remanufactured products. The network externality of remanufactured product is considered in the second period only, where [8];

- (9)

- Both the OEM and the TPR aim to maximize their total profits over the two-period horizon [43];

- (10)

- The CLSC members’ discount factor in the two periods is 1 [8].

3.4. Demand Functions

4. Model Formulation and Solution

4.1. Model A (Authorization Remanufacturing)

4.2. Model O (Outsourcing Remanufacturing)

5. Model Analysis

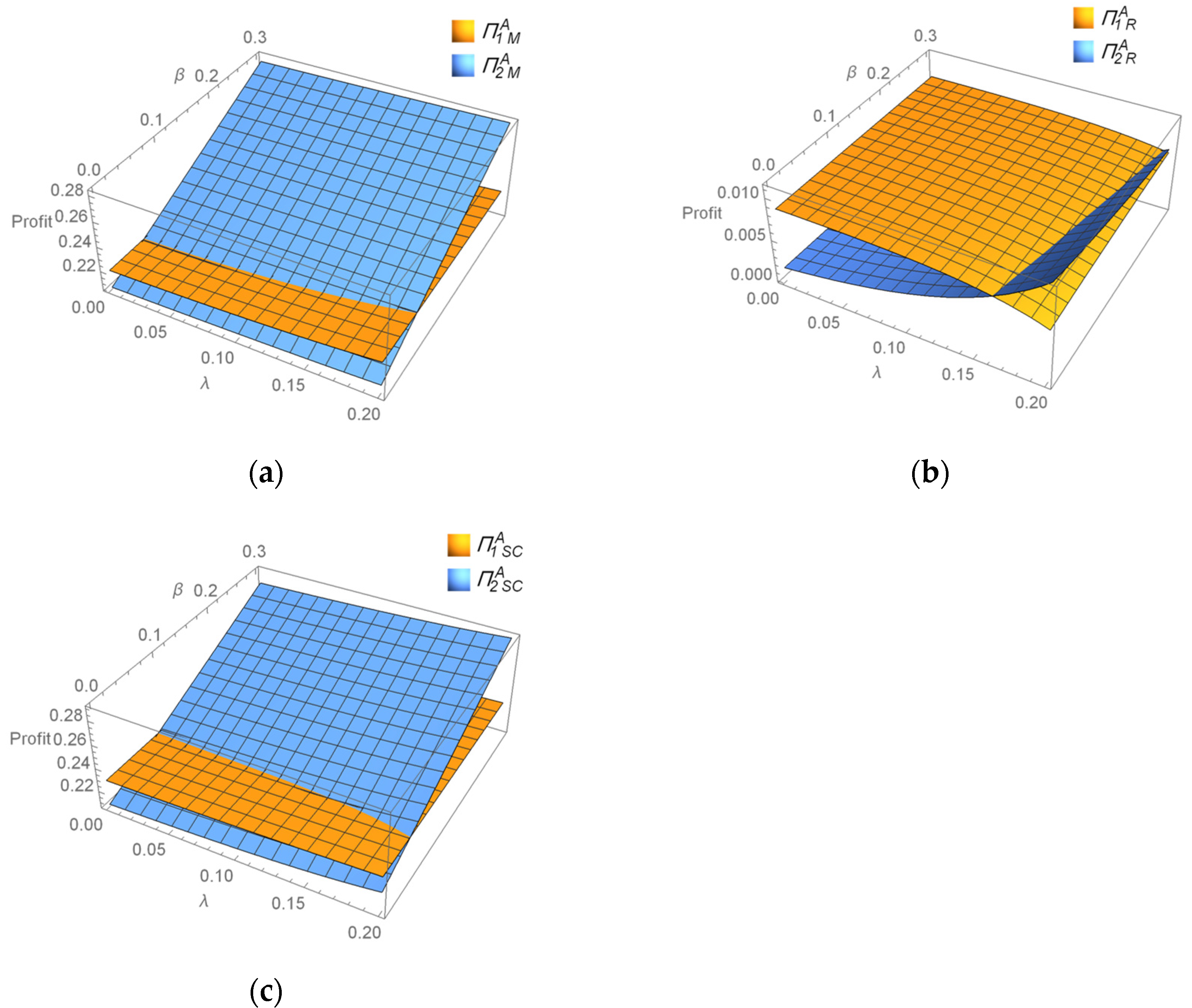

- (1)

- In Model A, if , the sequence is OEM > Consumer > TPR; otherwise, Consumer > OEM > TPR.

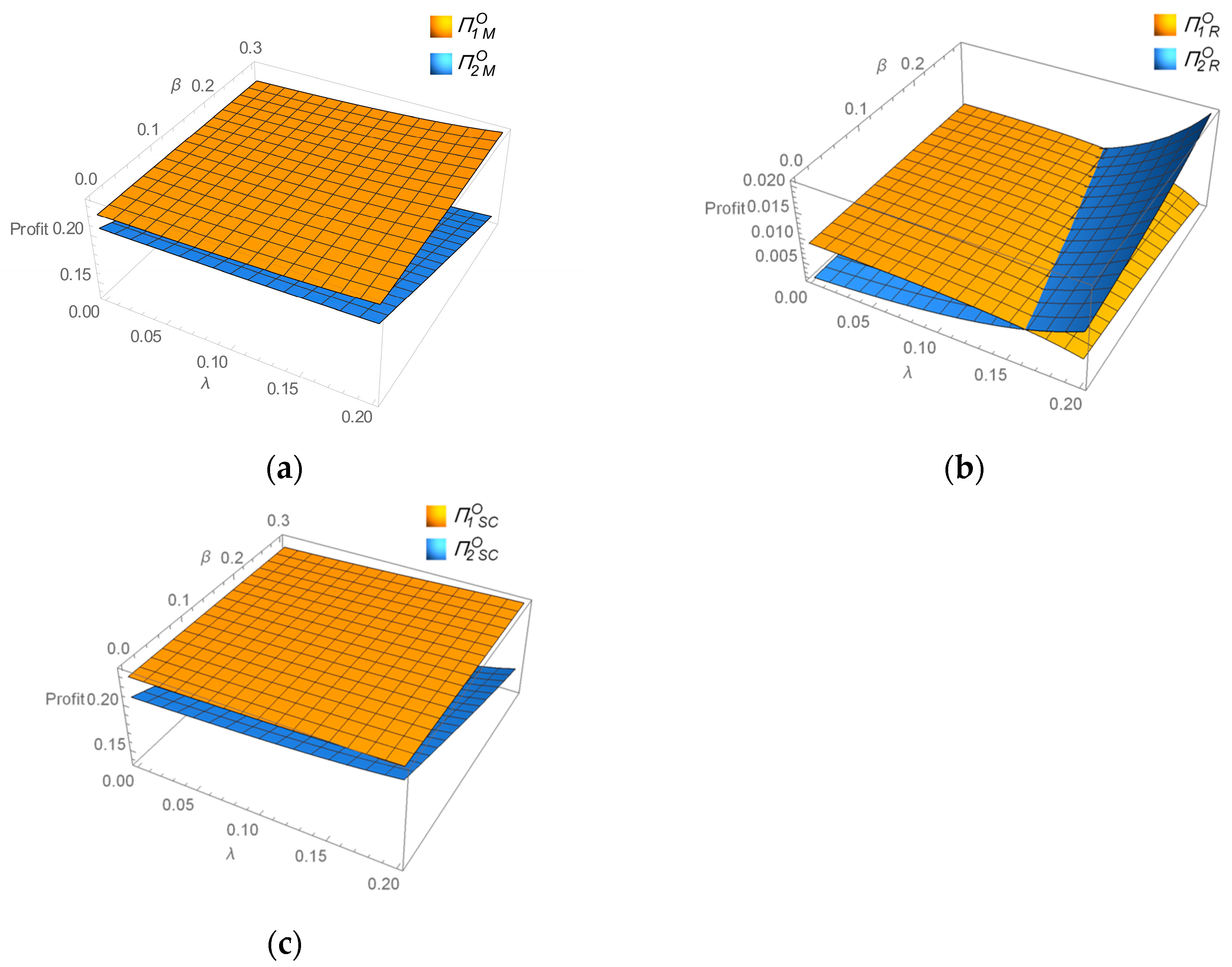

- (2)

- In Model O, if , the sequence is OEM > Consumer > TPR; otherwise, Consumer > OEM > TPR.

- (1)

- , .

- (2)

- ; ifor bothand,; otherwise,, where,.

- (1)

- ,.

- (2)

- Only ifand,; otherwise,, where,.

- (1)

- OEM:,.

- (2)

- TPR:,.

- (1)

- Only ifand,; otherwise,.

- (2)

- .

- (3)

- Only ifand,; otherwise,.

- (1)

- ,,,.

- (2)

- ,,.

- (3)

- ,,.

- (1)

- In the first period, it is more beneficial for consumers to purchase a remanufactured product in Model O, as they can reduce the spending on remanufactured products.

- (2)

- In two models, there is no difference in the sales price of new products in the first period. Meanwhile, the sales price of new products in the second period in Model A is higher than that in Model O. Usually, the sales price of a remanufactured product in Model A is higher than that in Model O; only when the certain condition is met do the consumers pay a lower price for a remanufactured product in the second period in Model A.

- (3)

- Model O is more favorable to the sales of remanufactured products, but the cannibalization of the new product market is also more obvious. Model A is beneficial to the sales of new products.

- (4)

- The TPR can obtain higher profit in Model O. Only when the contrast/assimilation effect and government subsidy level are both relatively low is Model A profitable for the OEM; otherwise, the OEM selects Model O. Similarly, for the entire CLSC, only under the condition that the contrast/assimilation effect and government subsidy level are both relatively low does Model A perform better than Model O; otherwise, Model O is more beneficial for the CLSC.

6. Numerical Analysis

6.1. The Comparison of Product Sales Volumes and Profits in CLSCs under Two Models

6.2. The Comparison of Environmental Impact, Consumer Surplus and Social Welfare in CLSCs under Two Models

6.3. The Comparison of Profits for CLSC Members and Entire CLSCs between the First Period and Second Period in Model A

6.4. The Comparison of Profits for CLSC Members and Entire CLSC between the First Period and Second Period in Model O

7. Discussion

7.1. Conclusions

- (1)

- When the conditions and are satisfied, the OEM prefers to select authorization remanufacturing; otherwise, the OEM prefers outsourcing remanufacturing. The outsourcing mode is always more beneficial for the TPR. Therefore, a win–win situation can be achieved between the OEM and the TPR under outsourcing remanufacturing through the government increasing subsidy or chain members advertising, hiring green brand spokesmen, etc., to increase the contrast/assimilation effect.

- (2)

- Model O only performs better than Model A in terms of sales of remanufactured products and environmental impact, while Model A is better in terms of consumer surplus and social welfare.

- (3)

- The contrast effect in Model A is beneficial to the OEM and CLSC, but harmful to the TPR. On the contrary, the impacts of the assimilation effect in Model O on OEM, TPR and CLSC are opposite this. Regardless of the remanufacturing mode, the enhancement of network externality could promote the sales of remanufactured products and improve the profits of CLSC members, while exacerbating the cannibalization of the new product market.

- (4)

- Regardless of the remanufacturing mode, government subsidy can significantly reduce consumer spending on remanufactured products. And, when the government subsidy policy ends, it still has a continuous impact on CLSC members’ decision making. In addition, CLSC members encroach the government subsidies which are offered to consumers through adjusting pricing.

7.2. Managerial Implications

- (1)

- Since the network externality of remanufactured products can improve the profits of the OEM/TPR/CLSC and promote the sales of remanufactured products, the OEM and the TPR are more motivated to enhance the network externality of remanufactured products. For example, the OEM can utilize consumers’ group psychology and design some reward mechanism to encourage more and more consumers to purchase remanufactured products.

- (2)

- The government should enact a higher government subsidy level, extend the implementation period of the policy and include remanufactured products in the list of the government’s priority procurements to promote the development of the remanufacturing industry. At the same time, the government should actively publicize the high quality and performance of remanufactured products through social media, social networks and other channels to guide the public to form a positive cognition of remanufactured products, thus attracting more and more consumers to purchase remanufactured ones.

7.3. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Nie, J.; Liu, J.; Yuan, H.; Jin, M. Economic and environmental impacts of competitive remanufacturing under government financial intervention. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2021, 159, 107473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, Z.; Hong, X.; Gong, Y.; Zhong, Q. Fuzzy closed-loop supply chain models with quality and marketing effort-dependent demand. Expert Syst. Appl. 2022, 207, 118081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbey, J.D.; Meloy, M.G.; Guide, V.D.R.; Atalay, S. Remanufactured Products in Closed-Loop Supply Chains for Consumer Goods. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2015, 24, 488–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbey, J.D.; Kleber, R.; Souza, G.C.; Voigt, G. The Role of Perceived Quality Risk in Pricing Remanufactured Products. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2017, 26, 100–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, P.; He, Y.; Xu, H. Channel structure and pricing in a dual-channel closed-loop supply chain with government subsidy. Int. J. Product. Econ. 2019, 213, 108–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.-H.; Zeng, D.-L.; Che, L.-P.; Zhou, T.-W.; Hu, J.-Y. Research on the profit change of new energy vehicle closed-loop supply chain members based on government subsidies. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2020, 19, 100937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.-M.; Li, Q.-W.; Liu, Z.; Chang, C.-T. Optimal pricing and remanufacturing mode in a closed-loop supply chain of WEEE under government fund policy. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2021, 151, 106951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Yuen, K.F. Analyzing the Effect of Government Subsidy on the Development of the Remanufacturing Industry. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sitcharangsie, S.; Ijomah, W.; Wong, T.C. Decision makings in key remanufacturing activities to optimize remanufacturing outcomes: A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 232, 1465–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yenipazarli, A. Managing new and remanufactured products to mitigate environmental damage under emissions regulation. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2016, 249, 117–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.; You, Z.; Yang, Y.; Chen, D.; Mukhopadhyay, S. Is third-party remanufacturing necessarily harmful to the original equipment manufacturer? Ann. Oper. Res. 2019, 291, 317–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, V.V.; Atasu, A.; van Ittersum, K. Remanufacturing, Third-Party Competition, and Consumers’ Perceived Value of New Products. Manag. Sci. 2015, 61, 60–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Liu, L.; Wang, Z. Competitive remanufacturing and pricing strategy with contrast effect and assimilation effect. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 257, 12–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.; Xiao, T.; Robb, D.J. Environmentally responsible closed-loop supply chain models with outsourcing and authorization options. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 278, 123791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, X.; Govindan, K.; Xu, L.; Du, P. Quantity and collection decisions in a closed-loop supply chain with technology licensing. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2017, 256, 820–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Z.-B.; Wang, J.-J.; Deng, G.-S.; Chen, H. Third-party remanufacturing mode selection: Outsourcing or authorization? Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2016, 87, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Chang, J.; Du, J. Dynamics analysis on competition between manufacturing and remanufacturing in context of government subsidies. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2019, 121, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; He, L.; Gen, M. Optimal strategies for the closed-loop supply chain with the consideration of supply disruption and subsidy policy. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2019, 128, 886–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.-Y.; Dimitrov, S.; Pun, H. The impact of government subsidy on supply Chains’ sustainability innovation. Omega 2019, 86, 42–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Huo, J.; Duan, Y. Impact of government subsidies on pricing strategies in reverse supply chains of waste electrical and electronic equipment. Waste Manag. 2019, 95, 440–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Fan, R.; Shen, L.; Miller, W. Recycling decisions of low-carbon e-commerce closed-loop supply chain under government subsidy mechanism and altruistic preference. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 259, 120883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, Z. Dynamic analysis of the decision of authorized remanufacturing supply chain affected by government subsidies under cap-and-trade policies. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2022, 160, 112237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Wu, H.; Deng, L. Decision-Making Based on Consumers’ Perceived Value in Different Remanufacturing Modes. Discrete Dyn. Nature Soc. 2015, 2015, 278210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Gao, S.; Gao, G.; Yang, R. Pricing decision of closed -loop supply chain under uncertainty of customer perceived value and recovery quality. Comput. Integr. Manuf. Syst. 2021, 27, 2476–2490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, T.; Li, C.; Chen, Y. Remanufacturing Strategy under Cap-and-Trade Regulation in the Presence of Assimilation Effect. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Meng, L.; Zhang, B.; Yang, Y. Differential pricing and strategy based on changeable perceived value of new product. Comput. Integr. Manuf. Syst. 2018, 24, 793–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, M.L.; Shapiro, C. Network Externalities, Competition, and Compatibility. Am. Econ. Rev. 1985, 75, 424–440. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Li, M.; Kou, J. Selling information products: Sale channel selection and versioning strategy with network externality. Int. J. Product. Econ. 2015, 166, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Y.; Yang, H. Wholesale pricing and evolutionary stable strategies of retailers under network externality. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2017, 259, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Li, Y.; Govindan, K.; Yue, X. Return policy and supply chain coordination with network-externality effect. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2018, 56, 3714–3732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; He, Y.; Ding, Q. The impact of network externalities and altruistic preferences on carbon emission reduction of low carbon supply chain. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2022, 29, 66259–66276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, B.; Li, W.; Zhao, D.; Jiang, P.; Modak, N.M. Effects of Network Externalities and Recycling Channels on Closed-loop Supply Chain Operation Incorporating Consumers’ Dual Preferences. Math. Probl. Eng. 2022, 2022, 3347303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Wang, C.; Xu, L. Decision for pricing, service, and recycling of closed-loop supply chains considering different remanufacturing roles and technology authorizations. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2019, 132, 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Meng, C.; Yuen, K.F. Remanufacturing authorization strategy for competition among OEM, authorized remanufacturer, and unauthorized remanufacturer. Int. J. Product. Econ. 2021, 242, 108295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, M.; Li, G.; Reimann, M. Team of rivals: How should original equipment manufacturers cooperate with independent remanufacturers via authorization? Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2022, 296, 837–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhou, H.; Wang, Y. Outsourcing remanufacturing and collecting strategies analysis with information asymmetry. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2021, 160, 107561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, X.; Li, M.; Li, B.; Wang, H. The Impact of Carbon Trade on Outsourcing Remanufacturing. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Sun, H.; Dong, H.; Gan, Y.; Koh, L. Outsourcing decision-making in global remanufacturing supply chains: The impact of tax and tariff regulations. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2023, 304, 997–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, W.; Mi, Y. Third-party remanufacturing mode selection for competitive closed-loop supply chain based on evolutionary game theory. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 263, 121305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, X.; Zhu, Q. Comparative analysis of three remanufacturing modes from game perspective. J. Syst. Eng. 2020, 35, 689–699+710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, J.; Ma, Z. Remanufacturing strategies of a brand owner under OEM mode. Ind. Eng. Manag. 2021, 26, 168–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Chen, J.; Diallo, C.; Venkatadri, U. Pricing and production decisions in a dual-channel closed-loop supply chain with (re)manufacturing. Int. J. Product. Econ. 2021, 232, 107935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Xiong, Y.; Jin, M. The entry of third-party remanufacturers and its impact on original equipment manufacturers in a two-period game-theoretic model. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 279, 123635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, P.; Du, J.; Nie, J.; Lu, Y. Impact of different power structure on technological innovation strategy of remanufacturing supply chain. Chin. J. Manag. 2016, 12, 1563–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Li, Q.; Zhang, H. Analysis of the Impact of Remanufacturing Process Innovation on Closed-Loop Supply Chain from the Perspective of Government Subsidy. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Chen, W.; Wang, W. Production and carbon emission reduction decisions for remanufacturing firms under carbon tax and take-back legislation. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2020, 143, 106419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, K.; He, P.; Liu, Z. Production and pricing decisions in a dual-channel supply chain under remanufacturing subsidy policy and carbon tax policy. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 2019, 71, 1199–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Research Paper | Government Subsidy | Consumers’ Perceived Value | Network Externality | Remanufacturing Mode | Game Theory |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zhou and Yuen [8] | ✓ | ✓ | Stackelberg | ||

| Xie et al. [32] | ✓ | Stackelberg | |||

| Agrawal et al. [12] | ✓ | / | |||

| Wu et al. [13] | ✓ | Stackelberg/Nash | |||

| Li et al. [23] | ✓ | ✓ | Stackelberg | ||

| Zhang et al. [7] | ✓ | ✓ | Stackelberg | ||

| Zhang and Zhang [22] | ✓ | ✓ | Stackelberg | ||

| Feng et al. [14] | ✓ | Stackelberg | |||

| Zhang et al. [39] | ✓ | ✓ | Evolutionary | ||

| This paper | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Stackelberg |

| Notations | Definitions |

|---|---|

| Indices | |

| Index of the periods (superscript): (first period) and (second period) | |

| Index of the remanufacturing modes (superscript): (authorization) and (outsourcing) | |

| Index of the CLSC members (subscript): (OEM), (TPR), and (CLSC) | |

| Index of the product types (subscript): (new) and (remanufactured) | |

| Index of the scenario with no government subsidy (superscript) | |

| Parameters | |

| Unit production cost of producing a new product | |

| Consumers’ perceived value of a new product | |

| Discount factor of consumers’ willingness to pay for remanufactured products | |

| Government subsidy to consumers who purchase remanufactured products | |

| The strength coefficient of the contrast/assimilation effect | |

| The strength coefficient of network externality | |

| Unit environmental impact of new products | |

| Unit environmental impact discount of remanufactured products relative to the new products | |

| The demand of product in the period under Model (, , ) | |

| The demand of product in two periods under Model (, ) | |

| The total demand of products in two periods under Model () | |

| The profit for in the period under Model (, , ) | |

| The profit for in two periods under Model (, ) | |

| Consumers’ actual payment of purchasing a remanufactured product in the first period under Model () | |

| Environmental impact under Model () | |

| Consumer surplus under Model () | |

| Social welfare under Model () | |

| Decision variables | |

| Unit outsourcing fee in Model O | |

| Sales price of product in the period under Model (, , ) | |

| The marginal profit of in remanufactured product in the period under Model (, , ) |

| 0.05 | 0.1 | 0.685 | 0.658 | 0.3131 | 0.338 | 0.451 | 0.403 | 0.0108 | 0.0113 | 0.462 | 0.414 |

| 0.2 | 0.696 | 0.639 | 0.3038 | 0.355 | 0.476 | 0.379 | 0.0106 | 0.0117 | 0.487 | 0.391 | |

| 0.3 | 0.704 | 0.614 | 0.2959 | 0.378 | 0.5 | 0.355 | 0.0105 | 0.0121 | 0.511 | 0.367 | |

| 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.654 | 0.618 | 0.358 | 0.395 | 0.454 | 0.406 | 0.0121 | 0.0129 | 0.466 | 0.419 |

| 0.2 | 0.667 | 0.592 | 0.345 | 0.421 | 0.478 | 0.383 | 0.0118 | 0.0135 | 0.49 | 0.396 | |

| 0.3 | 0.678 | 0.56 | 0.333 | 0.456 | 0.502 | 0.36 | 0.0115 | 0.0142 | 0.514 | 0.374 | |

| 0.15 | 0.1 | 0.611 | 0.561 | 0.4196 | 0.476 | 0.457 | 0.411 | 0.0138 | 0.0152 | 0.471 | 0.426 |

| 0.2 | 0.629 | 0.526 | 0.3993 | 0.516 | 0.481 | 0.388 | 0.0133 | 0.0162 | 0.495 | 0.404 | |

| 0.3 | 0.644 | 0.479 | 0.3825 | 0.571 | 0.505 | 0.366 | 0.0129 | 0.0175 | 0.518 | 0.384 | |

| 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.55 | 0.477 | 0.506 | 0.596 | 0.463 | 0.418 | 0.0164 | 0.0187 | 0.479 | 0.436 |

| 0.2 | 0.576 | 0.422 | 0.475 | 0.665 | 0.486 | 0.396 | 0.0156 | 0.0204 | 0.501 | 0.417 | |

| 0.3 | 0.597 | 0.345 | 0.45 | 0.763 | 0.509 | 0.377 | 0.0149 | 0.0229 | 0.524 | 0.4 |

| 0.05 | 0.1 | 0.262 | 0.258 | 0.221 | 0.196 | 0.4 | 0.331 |

| 0.2 | 0.263 | 0.256 | 0.233 | 0.184 | 0.435 | 0.298 | |

| 0.3 | 0.265 | 0.252 | 0.245 | 0.172 | 0.47 | 0.266 | |

| 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.261 | 0.256 | 0.222 | 0.198 | 0.405 | 0.337 |

| 0.2 | 0.262 | 0.254 | 0.235 | 0.187 | 0.439 | 0.305 | |

| 0.3 | 0.263 | 0.25 | 0.247 | 0.175 | 0.474 | 0.274 | |

| 0.15 | 0.1 | 0.259 | 0.254 | 0.225 | 0.202 | 0.411 | 0.346 |

| 0.2 | 0.261 | 0.251 | 0.237 | 0.191 | 0.445 | 0.316 | |

| 0.3 | 0.262 | 0.246 | 0.249 | 0.18 | 0.48 | 0.288 | |

| 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.256 | 0.25 | 0.229 | 0.208 | 0.422 | 0.361 |

| 0.2 | 0.258 | 0.246 | 0.24 | 0.199 | 0.454 | 0.334 | |

| 0.3 | 0.26 | 0.241 | 0.252 | 0.192 | 0.488 | 0.312 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hu, Y.; Meng, L.; Xue, J.; Xia, H. Authorization or Outsourcing: Considering the Contrast/Assimilation Effect and Network Externality of Remanufactured Products under Government Subsidy. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10766. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151410766

Hu Y, Meng L, Xue J, Xia H. Authorization or Outsourcing: Considering the Contrast/Assimilation Effect and Network Externality of Remanufactured Products under Government Subsidy. Sustainability. 2023; 15(14):10766. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151410766

Chicago/Turabian StyleHu, Yuqing, Lijun Meng, Jingya Xue, and Hongying Xia. 2023. "Authorization or Outsourcing: Considering the Contrast/Assimilation Effect and Network Externality of Remanufactured Products under Government Subsidy" Sustainability 15, no. 14: 10766. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151410766

APA StyleHu, Y., Meng, L., Xue, J., & Xia, H. (2023). Authorization or Outsourcing: Considering the Contrast/Assimilation Effect and Network Externality of Remanufactured Products under Government Subsidy. Sustainability, 15(14), 10766. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151410766