1. Introduction

With the intensification of informatization and networking trends, organizations in a dynamic competitive environment gradually show new features such as non-boundary features, bureaucracy, and flattening [

1]. The collaborative innovation team comprises high-quality talents from, among others, enterprises and universities and has become a critical organizational form for carrying out innovation activities. Under circumstances in which the time allocated for innovation research and development (R & D) is significantly shortened and innovation tasks are complex and changeable, the team and the organization can no longer obtain the resources required for innovation activities by themselves. Instead, they must establish connections with other organizations through team boundary-spanning activities and obtain complementary resources to improve innovation performance. Therefore, boundary-spanning activities have become an essential issue for scholars from the innovation perspective. However, the existing literature mainly focuses on how to improve team innovation performance through factors within the team, such as leadership style [

2,

3], team composition [

4,

5], the characteristics of team members [

6,

7,

8], team atmosphere [

9,

10,

11] and team human resource management [

12]. Research on the influence of collaborative innovation boundary-spanning activities on team innovation performance and research on the intermediate transformation mechanism is relatively scarce. We cannot find references for how the collaborative team can improve innovation performance through boundary-spanning activities.

Team boundary-spanning activities refer to a dynamic and complex process in which sub-teams under a collaborative innovation team reach a consensus on method, work plan, personnel allocation, and performance goals in the process of communication, cooperation, and R & D to design and craft the expected task at the team level and guarantee the smooth completion of expected goals. Meanwhile, teamwork will eventually be executed and completed by team members inclined to design their work independently. Team members will craft their work by adjusting tasks and relation boundary-spanning activities based on their objectives, significance, and abilities [

13]. Therefore, team job crafting and individual job crafting triggered by team boundary-spanning activities may become a meaningful way to improve team innovation performance. Existing research on job crafting mainly focuses on the antecedents of individual job crafting and their influence on employees’ innovation behavior and job performance. Specifically, individual job crafting’s antecedents include innovative team climate [

14], work engagement [

15], and the congruence between job characteristics and other team internal factors. Related research also discusses individual job crafting’s influence on job satisfaction [

7,

16], innovation behavior [

17,

18], and working performance [

19]. However, most studies are independent of each other. It is still being determined whether individual job crafting mediates between its antecedent factors and the resulting consequences; the same holds for team job crafting [

20]. It is necessary to distinguish between individual and team job crafting. In order to uncover the “black box” of how team boundary-spanning activities affect team innovation performance, it is also required to investigate further the mediating mechanism between such activities and team innovation performance.

The main objectives of this study are (1) analyzing the impact of the boundary-spanning activities of collaborative innovation teams on team innovation performance; (2) investigating whether job crafting mediates the relationship between boundary-spanning activities and the team innovation performance of collaborative innovation teams, and examining the different mediating roles of team job crafting and individual job crafting in the relationship between boundary-spanning activities and the team innovation performance of collaborative innovation teams; (3) Further analysis of the relationship between team boundary-spanning activities and team innovation performance through a double-difference “quasi-natural experiment” (4) providing advice to collaborative innovation teams about how to improve team innovation performance by using team boundary-spanning activities.

Compared with the existing literature, this paper makes the following contributions: 1. Few studies on team innovation performance have been empirically analyzed from the perspective of boundary-spanning team activities. 2. analyzed how boundary-spanning team activities affect team innovation performance through two mediating variables, team job crafting and individual job crafting, and then clarified the interaction mechanism between them. 3. A PSM-DID model was applied to reduce the endogeneity between boundary-spanning team activity and team innovation performance, using whether boundary-spanning team activity occurred as a quasi-natural experiment to make the conclusions more convincing.

2. Theory and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Influence of the Boundary-Spanning Activities of Collaborative Innovation Teams on Team Innovation Performance

Faced with intensified global competition and a changing market, organizations must continuously carry out innovative activities to meet challenges [

21,

22,

23]. Due to the limitations of isolated information and resources, collaborative innovation teams need to carry out boundary-spanning activities to build a link with external organizations [

24] and intentionally introduce and apply new ideas, processes, products, or new procedures and valuable to the team. Innovation performance is the result of the innovation activities of collaborative innovation teams [

25], which is an effective indicator used to measure the quality and efficiency of the innovation behavior of the team. Team boundary-spanning activities refer to managing the relationship between a team and external stakeholders, including mission coordinator activities, working with external teams to complete missions, scouting activities, and ambassadorial activities abroad [

24].

First, the ambassador activities of collaborative innovation teams refer to the interaction between team members and external higher-level organizations, which reflects the vertical dimension of team boundary-spanning activities. The resource dependence theory indicates that obtaining more key resources is vital for a team to improve its innovation performance. A collaborative team’s diplomatic behavior improves collaborative innovation team performance, including introducing its goal, value, and market potential to the higher-level organization, obtaining their understanding, appreciation, and support, and assisting the team in acquiring essential innovative resources.

Second, the task coordinator activities of the collaborative innovation team refer to the communication, coordination, negotiation, and feedback between internal members and external partners to successfully achieve the innovative goal [

26,

27,

28]. The coordination behavior reflects the collaborative innovation team’s boundary-spanning activities on the horizontal dimension. Due to the inconsistency of work ethic, method, and schedule, the collaborative innovation team shall hold regular or temporary meetings to check work progress and work quality and decide on the future work plan and method according to the current work status. Bertin and Truijen et al. pointed out that collaborative innovation teams can better integrate and allocate their innovation resources through coordination behaviors and promote innovation projects’ progress, thus ensuring innovation performance targets’ achievement [

29,

30,

31].

Finally, the scout activities of collaborative innovation teams refer to the behavior whereby team members pay attention to external partners to obtain necessary information and related technologies, which reflects the competitive dimension of boundary-spanning activities. Based on the innovative project’s expected goal, collaborative innovation team members constantly scan the external environment and search for relevant information so that they can have access to information related to consumer preferences and the development trend of market competition. This is not only helpful to the interactive optimization and improvement of team innovation, but it can also help the collaborative innovation team detect external threats in time and avoid the risks of innovation. This will help improve the innovation team’s performance [

32,

33]. Hence, we hypothesize:

H1. The boundary-spanning activities of collaborative innovation teams significantly positively impact team innovation performance.

2.2. Mediating Role of Team Job Crafting

Team job crafting refers to the decision of team members to change their work content and approach through close collaboration and communication [

34,

35]. First, the boundary-spanning activities of collaborative innovation teams considerably impact the crafting of teamwork. The ambassador activities in boundary-spanning activities win the understanding and support of the superior leaders. Consequently, the team has more freedom in defining and executing its innovation tasks. In a collaborative innovation team with high discretion, team members can independently make collective decisions and cooperate, which promotes job crafting at the team level. The coordination behavior in the boundary-spanning activity enhances the task interdependence of the entire team with other external units. Leana and Cuguero-Escofet believe that in a work situation with a high task interdependence, members are more willing to participate in a cooperative negotiation process to change traditional work practices and solve problems more efficiently. Meanwhile, scout activities can make team members feel the pressure resulting from the competitive climate, creating a solid atmosphere of teamwork and improving the willingness of team members to make collective decisions and work together to achieve the same goal [

34,

35,

36].

Second, team job crafting can improve the innovation performance of collaborative innovation teams. Tims and Chen et al. found that team job crafting can significantly promote work engagement at the team level [

37,

38]. This is because team job crafting enables the team to make independent decisions, integrate resources, restructure tasks, and adjust work, which not only stimulates the enthusiasm of the whole team but also improves the matching degree of each team member with the work, thus stimulating the creativity of the team. Mattarelli and Tagliaventi found that the technology developers of the company can bring positive organizational changes through team job crafting [

39,

40]. This shows that the work team has a personal initiative and can integrate organizational resources through cooperation to activate organizational creativity. Thus, we hypothesize:

H2. Team job crafting plays a mediating role in the impact of team boundary-spanning activities on team innovation performance.

2.3. Mediating Effect of Individual Job Crafting

Individual job crafting is an active adjustment team members make based on the traditional top-down job design. According to their job contents, they independently reconstruct and adjust job tasks and relationships with other members, highlighting individuals’ initiative and enthusiasm [

41]. Specifically, the collaborative innovation team establishes interaction with external related subjects to achieve a common innovation goal. After establishing the innovation goal of the team through boundary-spanning activities, the team leader would refine the overall team task and designate a specific task for each team member. After receiving their job task, each team member will reinterpret the characteristics of the job they undertake according to their cognitive framework and complete the job task based on the job crafting to contribute to the improvement of the team’s innovation performance.

Similarly, individual job crafting also positively impacts the innovation performance of collaborative innovation teams. First, individual job crafting can increase team members’ work input, guide them to actively apply valuable ideas in their job, and improve their work efficiency and the innovation performance of the whole team. Bakker et al. and Petrou et al. found that employees’ job-crafting behavior, actively seeking work resources and accepting work challenges, can significantly enhance their commitment to work [

42,

43]. Team members immersed in their job showed higher levels of innovation performance [

44,

45]. Second, individual job crafting is goal-oriented proactive behavior. Team members can mobilize their positive emotions while pursuing goals and realizing self-value. Specifically, team members in a positive mood are more inclined to accept challenging work and have a higher sense of self-efficacy when solving work difficulties creatively, which helps employees improve their innovation performance. Therefore, we hypothesize:

H3. Individual job crafting plays an intermediary role in the impact of team boundary-spanning activities on team innovation performance.

2.4. Chain Mediating Effect of Team Job Crafting and Individual Job Crafting

First, in modern organizations, teams gradually become the basic unit of work. Organizations finish complex, innovative tasks, increase their flexibility, and improve overall performance, and they do this using teams [

46]. In this case, when collaborative innovation teams implement boundary-spanning activities to improve performance, crafting at the team level will build team norms characterized by innovation and job crafting. These team norms represent the requirements and expectations of employees’ behaviors and guide the employees to craft their job based on team job-crafting objectives and requirements and performance standards. This is the so-called concretive control [

47]. Second, employees’ crafting activities under the influence of team job crafting can be expanded due to the observance, learning, and imitation among all employees [

48,

49]. Whether the employee can implement job crafting becomes a criterion of his integration into the team. Thus, we hypothesize:

H4. Team job crafting and individual job crafting play a mediating role in team boundary-spanning activities affecting team innovation performance.

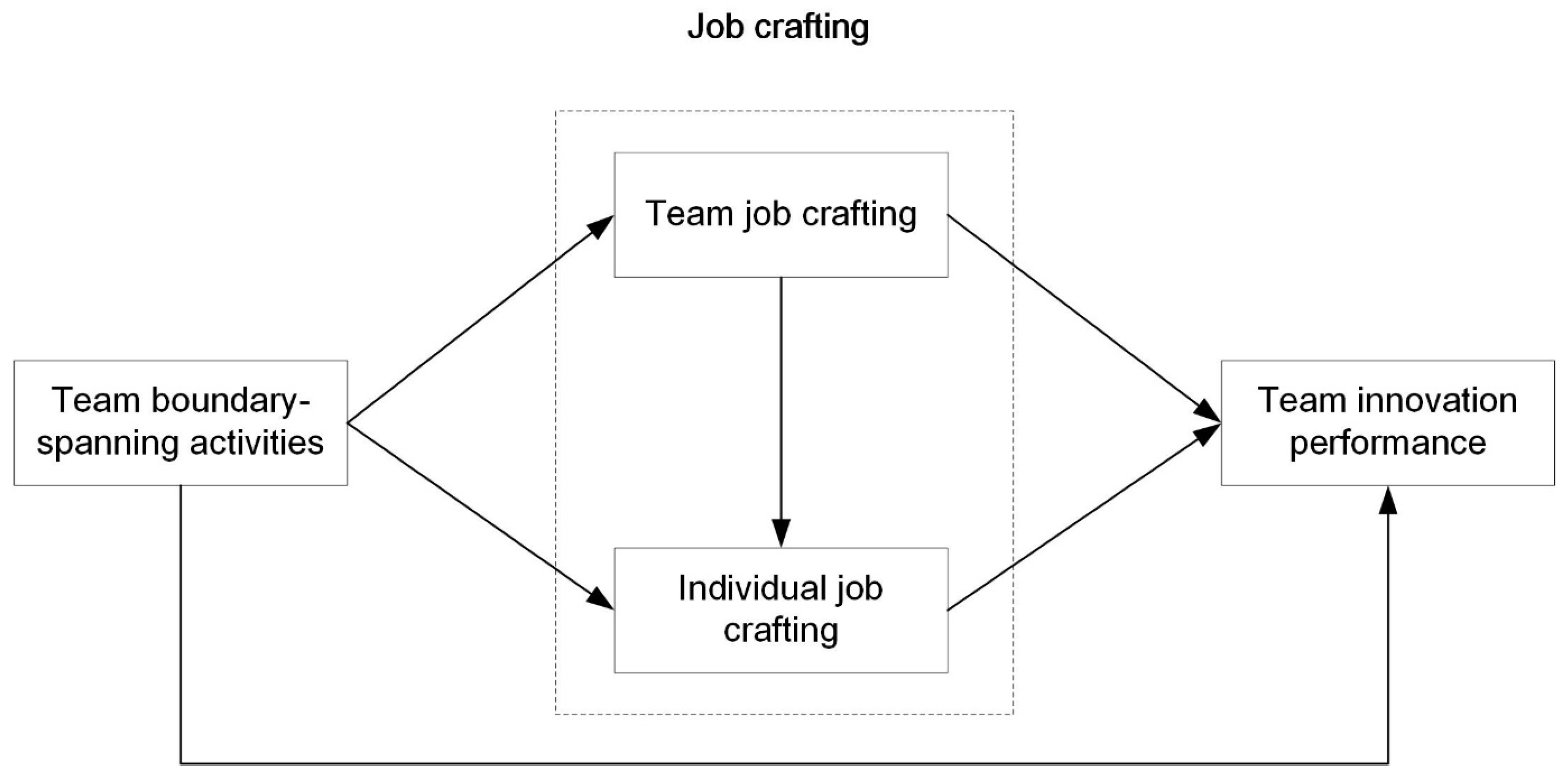

The theoretical research framework of the influencing mechanism of the boundary-spanning activities of teams on team innovation performance is proposed, as shown in

Figure 1.

3. Research Design

3.1. Sample and Data Collection Procedure

A questionnaire survey was used to evaluate the suggested model. First, the initial questionnaire was designed by referring to the mature scale in the relevant classical literature. The referent-shift consensus model proposed by Chan [

50] was used in designing the questionnaire, which means that variables including “team boundary-spanning activities”, “team job crafting”, and “team innovation performance” was designed from the perspective of the team. A request was made for these questions to be answered from the perspective of team awareness. The “individual job crafting” variable was designed from the employees’ perspective. Second, the terminology, the clarity of the instructions, and the structure of the questionnaire’s responses were evaluated by three subject-matter experts and five teams from Shandong province’s universities engaged in scientific research and innovation. Modifications were made accordingly. Finally, teams that were developing collaborative innovation projects were selected. The distribution of 456 surveys resulted in the recovery of 400 questionnaires. Three hundred thirty-one valid surveys were retrieved after invalid data had been removed; these originated from 41 collaborative innovation teams. The characteristics of the teams are shown in

Table 1.

3.2. Measures

Except where otherwise noted, the response format for all the measurement scales uses a five-point Likert-type scale with anchors from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

3.2.1. Team Boundary-Spanning Activities

Team boundary-spanning activities are measured by using the instrument developed by Ancona and Caldwell [

50], including three dimensions of ambassador activities (12 items), task coordinator activities (five items), and scout activities (four items). An example item of ambassador activities is “absorb outside pressures for the team so it can work free of interference”; an example item of task coordinator activities is “resolve design problems with external groups”; an example item of scout activities is “scan the environment inside or outside the organization for marketing ideas/expertise”.

3.2.2. Job Crafting

Utilizing 15 items modified from Slemp and Vella–Brodrick, job crafting was evaluated [

51]. The three crafting dimensions on this scale are task crafting, relational crafting, and cognitive crafting. There are five elements per dimension. An example item of task crafting is “choose to take on additional tasks at work”; an example item of relational crafting is “make an effort to get to know people well at work”; an example item of cognitive crafting is “think about how your job gives your life purpose”.

Table 2 provides a basic introduction to team cross-border activities.

3.2.3. Team Innovation Performance

Team innovation performance was measured by using nine items developed by Bishop et al. [

52]. This instrument includes two dimensions, namely, growth performance (e.g., to better comprehend the underlying principles of certain phenomena) and task performance (e.g., lowering development costs for products or processes).

3.2.4. Common Method Variance

A self-reported questionnaire was used to gather the data. Therefore, the common-method variation (CMV) could pose a risk to the reliability of empirical findings. Thus, this paper detects potential CMV by performing a full covariance test (FCT) on all measured problem items and shows the maximum value of VIF for each dimension in

Table 3, and the maximum value of VIF measured in all dimensions is lower than the maximum acceptable value of 3.3, from which it can be inferred that there is no interference of CMV in this paper. In addition, the CMV was tested again using the Harman one-way method [

53]. The results showed that the characteristic root of each factor was more significant than 1, explaining 69.251% of the total variance. The first factor explained 22.018% of the total variance, not more than 50% [

54], so the CMV was not a serious problem.

3.2.5. Reliability and Validity Analysis

The Smart PLS3.0 program used confirmatory factor analysis to evaluate the measurement model. Convergent validity aims to guarantee the multiple-item constructions’ unidimensionality and eliminate unreliable items [

55]. All items must load significantly (

p < 0.05,

t ≥ 2.0)and at a figure of at least 0.70 on their respective hypothesized components [

56]. After deleting items with a factor loading of less than 0.5, the factor loading value of the remaining items is between 0.704 and 0.818.

The reliability of each item in a construct can be assessed collectively by looking into composite reliability (CR) and average variance extracted (AVE). The CR and AVE must be at least 0.70 and 0.5, respectively, for a construct to be considered reliable [

57].

Table 3 demonstrates that all structures’ acceptable CR and AVE.

The discriminant validity was evaluated by contrasting the shared variances of components with the AVE of individual factors [

58,

59]. As a result, the discriminant validity was supported by the finding that the shared variance between the factors was less than the AVE of the individual factors.

Table 4 shows the calculated values of HTMT, which is the ratio of the average correlation of each variable question item to the average correlation of the other variable question items. The calculated HTMT values of all variables were less than 0.9, and the measurement model could be considered to have good discriminant validity. Hence, The measurement model showed sufficient convergent, discriminant, and reliability validity.

3.3. Analysis Results

The direct effects among variables are shown in

Table 5, and the mediating effects of individual job crafting and team job crafting in the relationship between team boundary-spanning activities and team innovation performance are shown in

Table 6. First, Team innovation performance was significantly impacted by team boundary-spanning activities. (b = 0.263,

p < 0.001). H1 was therefore supported. Second, team job crafting strongly moderated the expected association between team boundary-spanning activities and team innovation performance. (b = 0.248

p < 0.001). Meanwhile, the 95% confidence interval of bootstrap = 5000 was [0.174, 0.328], excluding 0. Hence, H2 was supported. Individual job crafting’s mediating role between team boundary-spanning activities and team innovation performance was insignificant. (b = 0.028,

p > 0.05). Therefore, H3 was not supported. The mediating chain effect of individual job crafting and team job crafting on team boundary-spanning activities and team innovation performance was significant (b = 0.025,

p < 0.001), and the 95% confidence interval of bootstrap = 5000 was [0.014, 0.040], excluding 0. Hence, H4 was supported.

4. Further Analysis

4.1. Sample Selection and Sources

This study examined 71 teams’ balanced panel data from January to November 2022. The teams engaged in boundary-spanning activities are utilized as the experimental group. In contrast, the other teams are employed as the control group, with June as the time turning point for analysis. Finally, there were 41 teams in the experimental group and 30 in the control group.

4.2. Variable Definition

4.2.1. Explained Variables

The explanatory variable in this paper is team innovation performance(IP), measured in two dimensions: growth performance and task performance. Thus the data from the relevant questions in the questionnaire are summed and averaged to arrive at this indicator.

4.2.2. Core Explanatory Variables

Team boundary-spanning activities (BSA) is the primary explanatory factor, and this paper treats the behavior of teams engaging in boundary-spanning activities as a policy shock and the cross-sectional term of the pilot team and pilot time grouping dummy variables as explanatory variables.

4.2.3. Control Variables

Drawing on relevant studies, task complexity, environmental uncertainty, team reflection, team heterogeneity, and task interdependence were selected as control variables in this paper. The processing of the data followed the data acquisition pattern of the explanatory variables.

4.3. Model Construction

In order to truly distinguish the impact of the behavior of a team performing boundary-spanning activities on team innovation performance, this paper controls for the differences between the research subjects before and after the activities are performed with the help of a double difference model, so the following model is constructed:

where

and

represent team

i’s period

.

is a dummy variable for the team’s boundary-spanning activity during the experimental period; a value of 1 means team

has engaged in boundary-spanning activity in period

, and a value of 0 means team

has no boundary-spanning activity in period

.

represents other variables that have an impact on team innovation performance other than the behavior of the boundary-spanning activity. In order to more precisely reflect the effects of time characteristics and individual characteristics on team innovation performance, and

are thus introduced, representing team-fixed effects and year-fixed effects, respectively.

represents the explanatory variable, indicating the innovation performance of team

in period

.

Table 7 shows the descriptive statistics of the samples to be analyzed using the difference-difference model.

Table 8 displays the regression results of team boundary-spanning activities on team innovation performance. The example without including the team, year fixed effects, and control variables is shown in column (1). The findings indicate that the regression coefficient of team boundary-spanning activities on team innovation performance is 15.899 (

p < 0.01). Column (2) illustrates the scenario where no control factors are added after correcting team and year effects, and column (3) indicates the case where control variables are added after correcting team and year effects, respectively. The findings demonstrate that All of the effects of team boundary-spanning activities on the effectiveness of the team’s innovation pass the 1% significance level. As seen in

Table 8, team boundary-spanning activities can significantly improve the innovation performance of teams. The innovation performance of teams involved in boundary-spanning activities is 14.449% higher than teams that do not engage in boundary-spanning activities. Therefore hypothesis 1 can be verified.

4.4. Robustness Tests

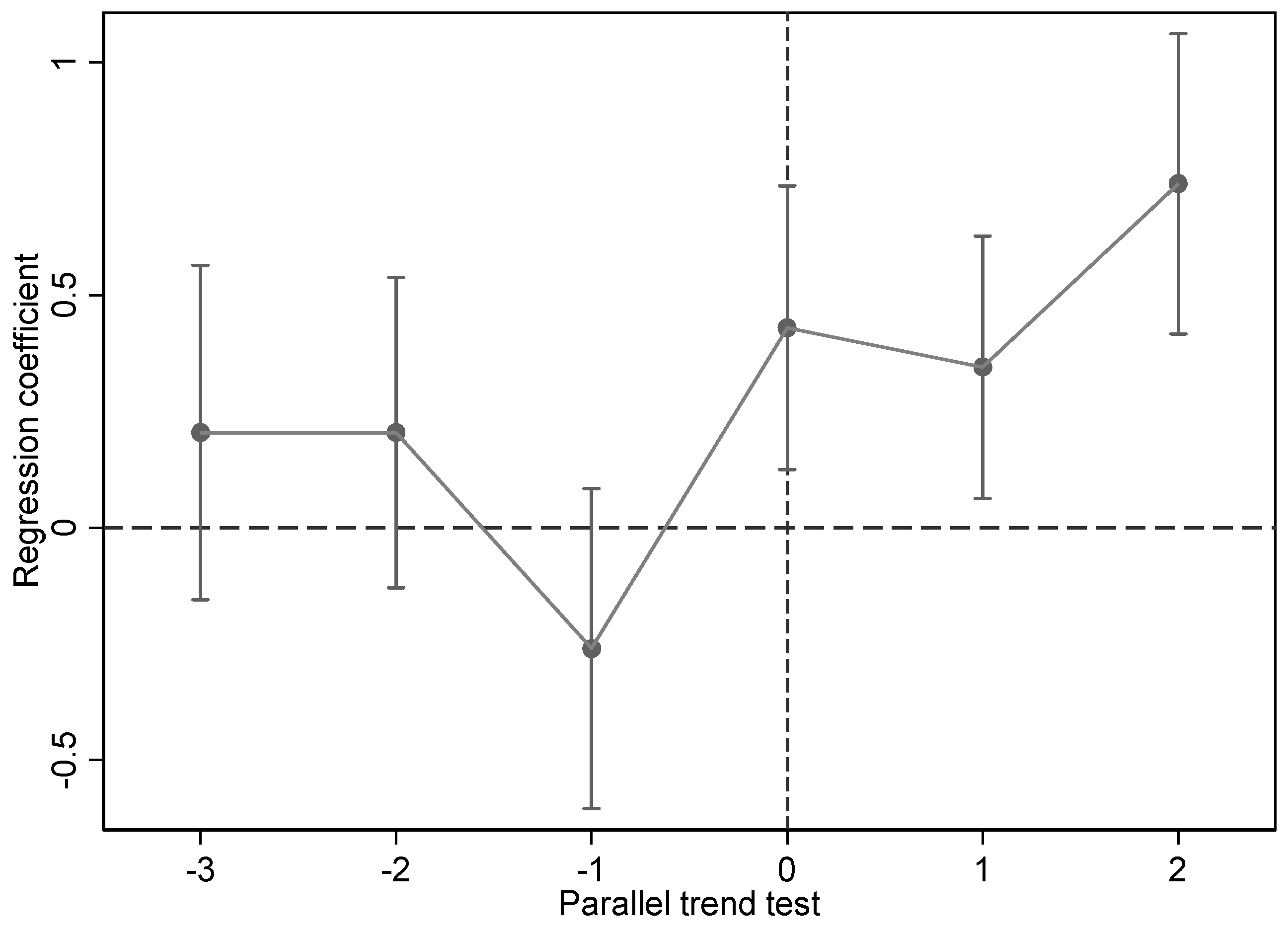

4.4.1. Parallel Trend Test

The experimental and control groups must have the same trend before the event, i.e., their innovation performance must maintain a comparatively stable trend over time prior to the team engaging in boundary-spanning activities for the difference in difference(did) to be valid. Thus, the parallel trend test in this paper uses the time study method to analyze further the dynamic impact of team boundary-spanning activities on innovation performance while testing the parallel trend hypothesis by constructing the following model:

where

is a dummy variable that represents the sample month during which the team’s boundary-spanning activity had an impact on the team, and a negative value denotes the month in which the team did not engage in the boundary-spanning activity; The definitions of the other variables are the same as those in the regression model (2). The base month is the first month the team engaged in boundary-spanning activities, and the difference between the treatment and control groups in the first month following that month is indicated. The results of parallel trend test are shown in

Figure 2, where it can be concluded that the estimated coefficient fluctuated around 0 before the team had no boundary-spanning activities in May and failed the test. This also shows that there was no discernible difference between the experimental group’s performance in innovation before the boundary-spanning activities and that of the control group. However, after the boundary-spanning activities, the estimated coefficients show a significant increase, showing that the team’s boundary-spanning activities positively affected the experimental group’s performance in terms of innovation.

4.4.2. Placebo Test

This paper conducts a placebo test by randomly assigning experimental groups. Specifically, 40 groups are randomly selected from the overall sample of 71 as the experimental group and the remaining as the control group. This is done to exclude that the boosting effect of team boundary-spanning activities on innovation performance receives interference from other unobserved factors and to ensure that the conclusions obtained are due to teams engaging in boundary-spanning activities. Additionally, the timing of this activity was randomly assigned and repeated 500 times. As well as the probability density distribution of the regression coefficient estimates, the scatter distribution of the corresponding

p-values, and the coefficient estimates,

Figure 3 also displays the coefficient estimates following the inclusion of control variables and team- and year-fixed effects in the benchmark regression. The sample’s coefficient estimations are found to be centered around 0. At the 10% confidence level, most of the estimates are not statistically significant, and the real behavioral effects diverge significantly from those of the placebo test. This suggests that the team innovation performance promotion effect induced by team boundary-spanning activities is not seriously confounded by other unobserved omitted variables, further validating the reliability of the benchmark findings.

4.4.3. Propensity Score Matching

This study uses propensity score matching to deal with the issue of potential bias in sample selection. To minimize systematic differences in innovation performance between teams, the method performs logit regressions on selected control variables with a dummy variable of whether the team performs boundary-spanning activities, and teams with similar resulting matched values are set as the control group. The results of verifying the parallelism in propensity score matching before and after matching are shown in

Table 9. Most of the

t-test results were insufficient to disprove the initial hypothesis that there was no systematic difference between the experimental and control groups before or after matching. As a result, the robustness of the results was guaranteed because there was no discernible systematic difference between the experimental and control groups used in this work, either before or after matching.

5. Conclusions and Discussion

We conducted a quasi-natural experiment on the behavior of teams engaging in boundary-spanning activities, exploring the impact mechanism of boundary-spanning activities on team innovation performance from the perspectives of team shaping, team, and individual job crafting. We selected 41 experimental and 30 control groups. Based on team data from January to November 2022, we used DID method to empirically analyze the impact of boundary-spanning activities on team innovation performance. The research results indicate that compared to teams without boundary-spanning activities, teams with boundary-spanning activities can directly improve team innovation performance. When the team is reflective and task interdependence is high, it promotes team innovation performance. Team job crafting mediates boundary-spanning activities’ positive impact on team innovation performance. Team and individual work crafting mediate between boundary-spanning activities of collaborative innovation teams and team innovation performance. This study explores the influencing mechanism of collaborative innovation team boundary-spanning activities on team innovation performance and further examines the mediating roles of team job crafting and individual job crafting in the positive relationship between team boundary-spanning activities and team innovation performance.

According to this study, collaborative innovation teams can perform better in the invention by engaging in boundary-spanning activities. The findings suggest that collaborative innovation teams can directly achieve innovation performance targets by engaging in boundary-spanning behaviors like ambassador activities, task coordinator activities, and scout activities. These behaviors have been shown to have a significant positive impact on team innovation performance. This finding is consistent with that of Yan et al. [

60], who emphasize the critical role of team boundary-spanning activities in team business model innovation.

Team job crafting mediates the impact of boundary-spanning activities on collaborative innovation teams’ performance in terms of invention. The empirical findings show that team job crafting is the only significant mediator of the association between boundary-spanning team innovation activities and team innovation performance. This shows that compared to individual job crafting, team job crafting can play a more critical role in delivering the positive effect of team job crafting boundary-spanning activities on team innovation performance. This conclusion is in line with the research of Kim et al. [

61] and Mäkikangas et al. [

62], demonstrating that the characteristics of team job crafting are essential antecedents of team job crafting and team job crafting is conducive to improving team performance.

Team innovation performance is positively impacted by collaborative innovation team boundary-spanning activities thanks to the chain mediation effect of individual and team job crafting. The findings demonstrate that while individual job crafting cannot mediate the relationship between collaborative team boundary-spanning activities and team innovation performance, team job crafting and individual job crafting have a chain-mediating effect on that relationship. This indicates that under the cross-boundary strategy implemented by the team, individual job crafting should be carried out based on team job crafting to improve the overall innovation performance of the team. This conclusion further supports the results of McClelland et al. [

63], who found that team job crafting is the premise and foundation of individual job crafting. The subsequent PSM-DID model showed that boundary-spanning team activities contributed to team innovation performance compared to non-border team activities. Team heterogeneity, reflection, interdependence, and environmental complexity significantly contributed to team innovation performance. From within the team, team heterogeneity and diversity of team members help to brainstorm new solutions, while team interdependence ensures that novel ideas are fully considered and implemented, thus promoting team innovation performance and team reflection to refine ideas and approaches in the final stage, resulting in a higher innovation factor. From outside the team, environmental complexity increases team innovation performance. If the environmental complexity is too low, there is little room for innovation, and the existence of a certain level of environmental complexity helps to expand the space for team innovation performance, leading to improved team innovation performance.

Team boundary crossing itself is a creative activity that not only provides an essential guarantee for the sustainable development of the team but also is a necessary means to enhance team innovation. According to resource dependency theory, the fundamental way for teams to enhance creativity is to obtain more real or potential resources. While crossing borders, teams consciously acquire more valuable resources such as work information, knowledge, and support and introduce and apply novel ideas, products, or procedures. Thus, team boundary crossing is an activity in which the team acquires more real or potential resources, thus facilitating the team’s innovative and creative activities while stimulating the team’s creativity. Team boundary crossing can collect external information and other resources related to the team’s tasks, which can help the team generate new ideas and make creative task improvement solutions; team boundary crossing will have extensive contact with external stakeholders and exchange ideas or cognitive patterns, thus breaking the established habits of thinking, stimulating creative thinking, and eventually forming new working concepts, which in turn will benefit the team’s innovative performance. In addition, the team crosses boundaries to discover internal activity defects through comparison with external ones, thus promoting communication and coordination among members, enhancing cohesion and activity, and ultimately promoting team creativity and innovation performance.

The openness of a team can be enhanced by increasing the heterogeneity of team members, which in turn improves team innovation performance. With the widespread application of economic globalization and networked information technology, the formation of cross-disciplinary, cross-organizational, and cross-regional open innovation teams has become the primary way to improve the innovation performance of teams. In fact, behind each member of a heterogeneous team exists a cross-organizational knowledge network established by the original learning experience or work experience. Through these cross-organizational networks, the innovation mode of the team becomes open innovation. The greater the degree of heterogeneity of members, the smaller the crossover between the cross-organizational networks of each member and the greater the breadth of the team’s boundary-spanning search for knowledge. In addition, compared with homogeneous teams, heterogeneous team members are more closely connected to external networks and have a more vital ability to acquire external knowledge, i.e., the greater the depth of boundary-spanning search, the greater the number of ideas, the more outstanding the possibility of innovation, and the higher the performance.

6. Theoretical Contribution

First, this study expands on the influencing factors of collaborative innovation team performance. With the acceleration of technological innovation and the constant changes in a competitive environment, boundary-spanning activities play an increasingly prominent role in improving team innovation performance. However, existing research mainly focuses on improving team innovation performance through factors within the team, such as leadership style, team composition, and team atmosphere. The influence of inter-team contact characteristics, such as the impact of boundary-spanning activities on team innovation performance, has received much too little attention. This study addressed the research gap in this area, increased our knowledge of the influencing elements of team innovation performance, and empirically assessed the impact of boundary-spanning activities on team innovation performance in collaborative innovation teams.

Second, based on the job crafting perspective, the influencing process of the collaborative innovation team’s boundary-spanning activities on team innovation performance is revealed. There still needs to be more studies on team job crafting compared to individual job crafting. Existing studies still need to thoroughly address the influence mechanism of team boundary-spanning activities on team innovation performance. Therefore, this study empirically analyzes the mediating roles of job crafting at the team and individual levels and the effect of the boundary-spanning activities of collaborative innovation teams on team innovation performance. Team job crafting has a more significant mediating effect on the positive relationship of boundary-spanning activities of collaborative innovation teams on team innovation performance than individual job crafting. A chain mediates the association between boundary-spanning team activities and team innovation performance between team job crafting and individual job crafting. This outcome illustrates not only the diversity of the team and individual job crafting but also the mechanism through which team boundary-spanning activities influence team performance in terms of job crafting.

6.1. Management Enlightenment

6.1.1. Actively Carry out Team Boundary-Spanning Activities

The boundary-spanning activities of collaborative innovation teams can directly promote team innovation performance. Therefore, collaborative innovation teams should select appropriate external partners and actively carry out boundary-spanning activities. Vertically, team leaders should take the initiative to clarify the importance and significance of innovative projects to senior leaders and strive for their understanding and resource support. Horizontally, teams should coordinate and negotiate with external partners on the joint mission and objectives and regularly check the project’s progress to ensure that the expected innovation performance targets are achieved. Furthermore, close attention should be paid to market changes and the dynamics of other competitors. Collect helpful information and timely adjust the teamwork according to available information so that teams can improve team innovation performance.

6.1.2. Attach Importance to Team Job Crafting

Team job crafting is a crucial mediator for collaborative innovation teams to improve innovation performance through boundary-spanning activities. Therefore, the collaborative innovation team carrying out boundary-spanning activities should pay attention to job crafting at the team level. The team leader should encourage members to share knowledge, exchange work experience, and make decisions collaboratively. The allocation of innovation resources possessed by the team should be planned and rationally distributed based on the team’s objectives and job requirements. A flexible working method should be developed to improve the job involvement and creativity of the whole team.

6.1.3. Encourage Employees to Craft Their Own Job

Job crafting and individual job crafting can successively mediate the positive effect of the collaborative innovation team’s boundary-spanning activities on innovation performance. Thus, team leaders should create a team climate that tolerates failure and encourages innovation. Employees should be encouraged to practice new working methods and discover innovative opportunities. Encourage employees to work in teams to craft their work tasks based on team job crafting, ultimately improving the positive effect of team boundary-spanning activities on innovation performance. Despite the contributions of this study to the literature, several limitations in this study warrant further attention and future research.

7. Limitations and Future Research

First, while this study provides robust empirical evidence of the influencing process of collaborative innovation teams boundary-spanning activities on team innovation performance, further research might use other methods (e.g., qualitative approaches) to capture more information about how collaborative innovation teams’ boundary-spanning activities influence team innovation performance.

Second, it is essential to examine the boundary conditions for team and individual job crafting and their mediating roles. This will provide collaborative innovation teams with valuable suggestions for improving innovation performance through boundary-spanning activities.

Third, the data sample is limited to China. Thus, the conclusions of this study may not be a statistical representation of the collaborative teams of other countries with different economic development environments. Further research can empirically validate the research model proposed in this study using data collected from other countries to generalize our findings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.Z. and X.T.; methodology, M.C.; software, C.L. and H.Z.; validation, H.Z. and M.C.; formal analysis, X.T. and C.L.; investigation, H.Z., X.T. and C.L.; resources, H.Z. and C.L.; data curation, X.T. and C.L.; writing—original draft preparation, H.Z. and M.C.; writing—review and editing, X.T. and C.L.; visualization, H.Z. and C.L.; supervision, M.C.; project administration, M.C.; funding acquisition, M.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Funding: This research was funded by Shandong Social Science Planning Project, China (Grant No. 21CJJJ17, 21BZBJ15); Shandong natural science foundation project, China (ZR2020mg008, ZR2022QG020); Qingdao Social Science Planning Project, China (QDSKL2201229, QDSKL2201231).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks are given to those who participated in the writing of this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Faraj, S.; Yan, A. Boundary work in knowledge teams. J. Appl. Psychol. 2009, 94, 604–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mascareño, J.; Rietzschel, E.; Wisse, B. Envisioning innovation: Does visionary leadership engender team innovative performance through goal alignment? Creat. Innov. Manag. 2020, 29, 33–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Zhang, H.M.; Wang, L.L. Adverse Effects of Leader Family-to-Work Conflict on Team Innovation. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2022, 69, 3101–3110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.-Y.; Huang, K.-F. The antecedents of innovation performance: The moderating role of top management team diversity. Balt. J. Manag. 2019, 14, 291–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.L.; Jiang, W.; Zhang, H.M.; Lin, H. Leader information seeking, team performance and team innovation: Examining the roles of team reflexivity and cooperative outcome interdependence. Inf. Process. Manag. 2020, 57, 102343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Shu, R.; Farh, C.I. Differential implications of team member promotive and prohibitive voice on innovation performance in research and development project teams: A dialectic perspective. J. Organ. Behav. 2019, 40, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Wu, C.S. Cross-level impact of employees’ knowledge management competence and team innovation atmosphere on innovation performance. Ann. Oper. Res. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildiz, H.E.; Murtic, A.; Klofsten, M.; Zander, U.; Richtner, A. Individual and contextual determinants of innovation performance: A micro-foundations perspective. Technovation 2021, 99, 102130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Wang, G.Z.; Ma, X. Environmental innovation practices and green product innovation performance: A perspective from organizational climate. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 28, 224–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.L.; Qu, M.; Li, M.M.; Liao, G.L. Team Leader’s Conflict Management Style and Team Innovation Performance in Remote R&D Teams-with Team Climate Perspective. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10949. [Google Scholar]

- Primus, D.J.; Jiang, C.X. Crafting better team climate: The benefits of using creative methods during team initiation. Int. J. Technol. Manag. 2019, 79, 299–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waheed, A.; Miao, X.M.; Waheed, S.; Ahmad, N.; Majeed, A. How New HRM Practices, Organizational Innovation, and Innovative Climate Affect the Innovation Performance in the IT Industry: A Moderated-Mediation Analysis. Sustainability 2019, 11, 621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y.; Kim, M.; Hur, W.-M. Interteam cooperation and competition and boundary activities: The cross-level mediation of team goal orientations. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; Jiang, L.; Wang, H.J. How to build your team for innovation? A cross-level mediation model of team personality, team climate for innovation, creativity, and job crafting. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2019, 92, 848–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Nambudiri, R. Work engagement, job crafting and innovativeness in the Indian IT industry. Pers. Rev. 2020. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, K.; Abildgaard, J.S. The development and validation of a job crafting measure for use with blue-collar workers. Work Stress 2012, 26, 365–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.; Bae, S.; Kim, H.; Ahn, S. The effect of job crafting behavior on innovative behavior focused on mediating effect of work engagement. Korean J. Resour. Dev. 2016, 23, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Wang, F.; Das, A.K. Work-Family Conflict on Sustainable Creative Performance: Job Crafting as a Mediator. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulshof, I.L.; Demerouti, E.; Le Blanc, P.M. Day-level job crafting and service-oriented task performance: The mediating role of meaningful work and work engagement. Career Dev. Int. 2020, 25, 355–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Parker, S.K. Reorienting job crafting research: A hierarchical structure of job crafting concepts and integrative review. J. Organ. Behav. 2019, 40, 126–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savelsbergh, C.; Gevers, J.M.; Van der Heijden, B.I.; Poell, R.F. Team role stress: Relationships with team learning and performance in project teams. Group Organ. Manag. 2012, 37, 67–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.N.; Chen, Y.F.; Ren, Y.; Jin, B.X. Impact mechanism of corporate social responsibility on sustainable technological innovation performance from the perspective of corporate social capital. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 308, 127345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.K.; Del Giudice, M.; Nicotra, M.; Fiano, F. How Firm Performs Under Stakeholder Pressure: Unpacking the Role of Absorptive Capacity and Innovation Capability. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2022, 69, 3802–3813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ancona, D.G.; Caldwell, D.F. Bridging the boundary: External activity and performance in organizational teams. Adm. Sci. Q. 1992, 37, 634–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Dreu, C.K.; Nijstad, B.A.; Bechtoldt, M.N.; Baas, M. Group creativity and innovation: A motivated information processing perspective. Psychol. Aesthet. Creat. Arts 2011, 5, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahiaga-Dagbui, D.D.; Tokede, O.; Morrison, J.; Chirnside, A. Building high-performing and integrated project teams. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2020, 27, 3341–3361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrone, J.A. Team boundary spanning: A multilevel review of past research and proposals for the future. J. Manag. 2010, 36, 911–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.F.; Zhang, F.T.; Chen, S.; Zhang, N.; Wang, H.L.; Jian, J. Member Selection for the Collaborative New Product Innovation Teams Integrating Individual and Collaborative Attributions. Complexity 2021, 8897784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertin, C.; Mavoori, H. Innovative Technology-Based Startup-Large Firm Collaborations: Influence of Human and Social Capital on Engagement and Success. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2022, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennington, D.D. Collaborative, cross-disciplinary learning and co-emergent innovation in eScience teams. Earth Sci. Inform. 2011, 4, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, N.; Wang, J.J. The influence of knowledge governance and boundary-spanning search on innovation performance. Mod. Phys. Lett. B 2020, 34, 2050326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, A.J.; Ormiston, M.E.; Wong, E.M. The effects of cohesion and structural position on the top management team boundary spanning–firm performance relationship. Group Organ. Manag. 2019, 44, 1099–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, C.A.; Francis, T.B.; Baker, J.E.; Georgiadis, N.; Kinney, A.; Magel, C.; Rice, J.; Roberts, T.; Wright, C.W. A boundary spanning system supports large-scale ecosystem-based management. Environ. Sci. Policy 2022, 133, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leana, C.; Appelbaum, E.; Shevchuk, I. Work process and quality of care in early childhood education: The role of job crafting. Acad. Manag. J. 2009, 52, 1169–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapica, L.; Baka, L. What is job crafting? A review of theoretical models of job crafting. Med. Pr. 2021, 72, 423–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuguero-Escofet, N.; Ficapal-Cusi, P.; Torrent-Sellens, J. Sustainable Human Resource Management: How to Create a Knowledge Sharing Behavior through Organizational Justice, Organizational Support, Satisfaction and Commitment. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tims, M.; Bakker, A.B.; Derks, D.; Van Rhenen, W. Job crafting at the team and individual level: Implications for work engagement and performance. Group Organ. Manag. 2013, 38, 427–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-Y.; Yen, C.-H.; Tsai, F.C. Job crafting and job engagement: The mediating role of person-job fit. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 37, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattarelli, E.; Tagliaventi, M.R. How offshore professionals’ job dissatisfaction can promote further offshoring: Organizational outcomes of job crafting. J. Manag. Stud. 2015, 52, 585–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, A.; Encarnacao, T.; Viseu, J.; Sousa, M.J. Job Crafting and Job Performance: The Mediating Effect of Engagement. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrzesniewski, A.; Dutton, J.E. Crafting a job: Revisioning employees as active crafters of their work. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2001, 26, 179–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Tims, M.; Derks, D. Proactive personality and job performance: The role of job crafting and work engagement. Hum. Relat. 2012, 65, 1359–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrou, P.; Demerouti, E.; Peeters, M.C.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Hetland, J. Crafting a job on a daily basis: Contextual correlates and the link to work engagement. J. Organ. Behav. 2012, 33, 1120–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mainemelis, C. When the muse takes it all: A model for the experience of timelessness in organizations. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2001, 26, 548–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, W.W. The Effects of Job Crafting on Job Performance among Ideological and Political Education Teachers: The Mediating Role of Work Meaning and Work Engagement. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathieu, J.E.; Hollenbeck, J.R.; van Knippenberg, D.; Ilgen, D.R. A century of work teams in the Journal of Applied Psychology. J. Appl. Psychol. 2017, 102, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, J.R. Tightening the iron cage: Concertive control in self-managing teams. Adm. Sci. Q. 1993, 38, 408–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postmes, T.; Spears, R.; Lea, M. The formation of group norms in computer-mediated communication. Hum. Commun. Res. 2000, 26, 341–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, R.K.; Woo, H.R. Influences of Boundary-Spanning Leadership on Job Performance: A Moderated Mediating Role of Job Crafting and Positive Psychological Capital. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, D. Functional relations among constructs in the same content domain at different levels of analysis: A typology of composition models. J. Appl. Psychol. 1998, 83, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slemp, G.R.; Vella-Brodrick, D.A. Optimising employee mental health: The relationship between intrinsic need satisfaction, job crafting, and employee well-being. J. Happiness Stud. 2014, 15, 957–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, K.; D’Este, P.; Neely, A. Gaining from interactions with universities: Multiple methods for nurturing absorptive capacity. Res. Policy 2011, 40, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cervantes, I.; Meuwissen, T.H.E. Maximization of total genetic variance in breed conservation programmes. J. Anim. Breed. Genet. 2011, 123, 465–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bollen, K.A. Structural Equations with Latent Variables; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1989; Volume 210. [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. On the evaluation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhang, H.; Li, Q.W. Moment-based evaluation of structural reliability. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2019, 181, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Fan, J.; Zhao, D.; Yang, S.; Fu, Y. Predicting consumers’ intention to adopt hybrid electric vehicles: Using an extended version of the theory of planned behavior model. Transportation 2016, 43, 123–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Hu, B.; Liu, G.; Ru, X.; Wu, Q. Top management team boundary-spanning behaviour, bricolage, and business model innovation. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2020, 32, 561–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Baek, S.I.; Shin, Y. The effect of the congruence between job characteristics and personality on job crafting. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mäkikangas, A.; Aunola, K.; Seppälä, P.; Hakanen, J. Work engagement–team performance relationship: Shared job crafting as a moderator. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2016, 89, 772–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClelland, G.P.; Leach, D.J.; Clegg, C.W.; McGowan, I. Collaborative crafting in call centre teams. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2014, 87, 464–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).