How Job Crafting Affects Hotel Employees’ Turnover Intention during COVID-19: An Empirical Study from China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Background of the Development of COVID-19

2.2. Job Crafting

2.3. Self-Regulation Theory

2.4. Job Crafting and Employee Metrics

2.4.1. Career Identity

2.4.2. Job Engagement

2.4.3. Turnover Intention

3. Methodology

3.1. Measures’ Development

3.2. Sample and Procedure

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA)

4.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

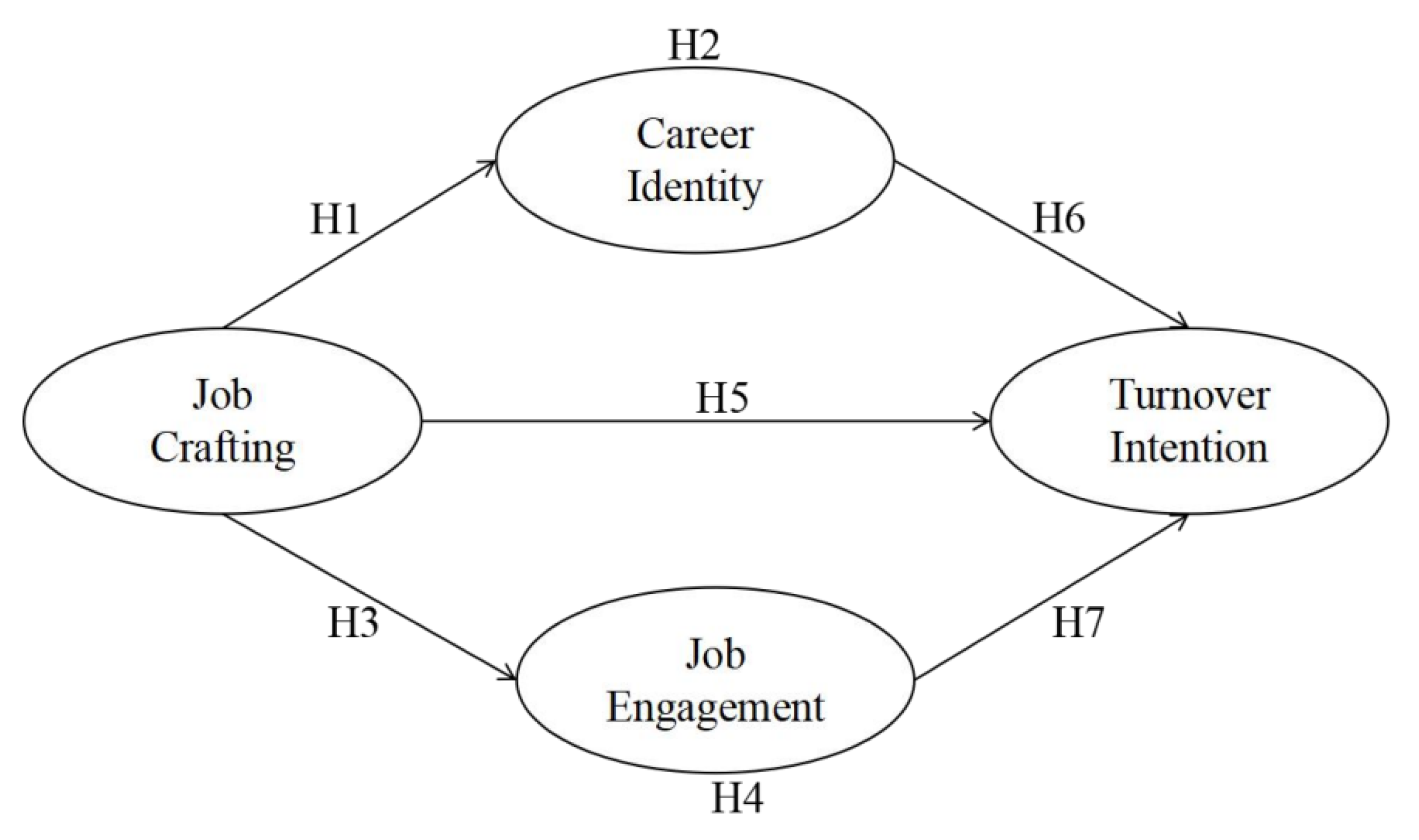

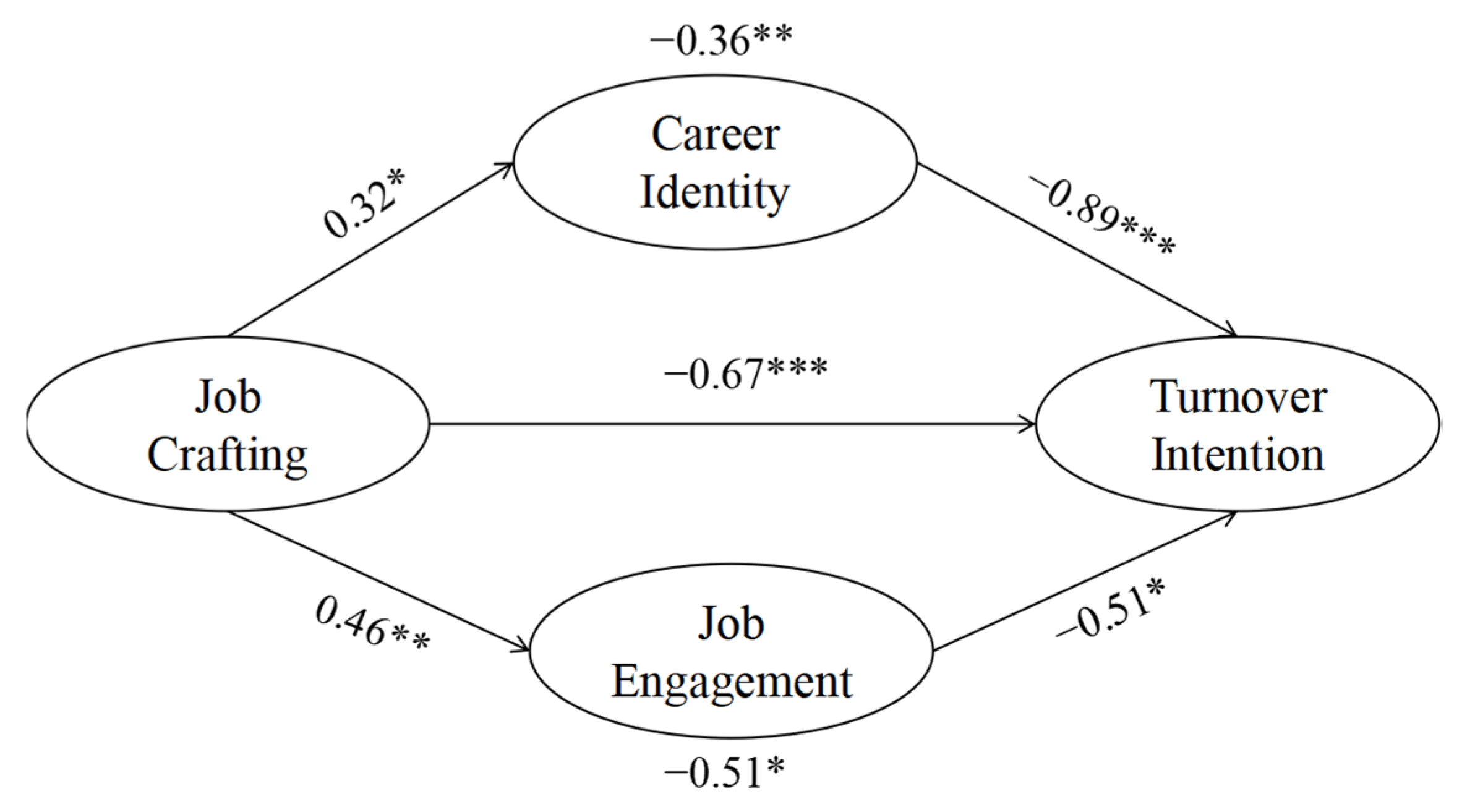

4.3. Structural Equation Modeling (SEM)

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

6. Limitations and Directions for Future Studies

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Paais, M.; Pattiruhu, J.R. Effect of motivation, leadership, and organizational culture on satisfaction and employee performance. J. Asian. Financ. Econ. 2020, 7, 577–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wikhamn, W. Innovation, sustainable HRM and customer satisfaction. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 76, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, M.C.; Wang, Y. Sustainable labor practices? Hotel human resource managers views on turnover and skill shortages. J. Human. Resour. Hosp. Tour. 2021, 10, 235–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, A.; Dhar, R.L. Linking frontline hotel employees’ job crafting to service recovery performance: The roles of harmonious passion, promotion focus, hotel work experience, and gender. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 47, 485–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, C.F.; Jang, S.S. An expectancy theory model for hotel employee motivation. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2008, 27, 313–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawakubo, A.; Oguchi, T. Recovery experiences during vacations promote life satisfaction through creative behavior. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2019, 30, 240–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Xie, C.; Morrison, A.M. The effect of corporate social responsibility on hotel employee safety behavior during COVID-19: The moderation of belief restoration and negative emotions. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 46, 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnenschein, K.; Barker, M.; Hibbins, R. Chinese international students’ perceptions of and reflections on graduate attributes needed in entry-level positions in the Chinese hotel industry. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2017, 30, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo, A.; Martín-Barroso, D.; Nunez-Serrano, J.A.; Turrión, J.; Velázquez, F.J. Does hotel management matter to overcoming the COVID-19 crisis? The Spanish case. Tour. Manag. 2022, 88, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Xu, J.; Zhang, T.C.; Li, Q.M. Effects of professional identity on turnover intention in China’s hotel employees: The mediating role of employee engagement and job satisfaction. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 45, 10–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohsin, A.; Lengler, J.; Kumar, B. Exploring the antecedents of intentions to leave the job: The case of luxury hotel staff. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 35, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, K.; Dutt, C.S.; Chathoth, P.; Daghfous, A.; Khan, M.S. The adoption of artificial intelligence and robotics in the hotel industry: Prospects and challenges. Electron. Mark. 2021, 31, 553–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slowiak, J.M.; DeLongchamp, A.C. Self-Care Strategies and Job-Crafting Practices Among Behavior Analysts: Do They Predict Perceptions of Work–Life Balance, Work Engagement, and Burnout? Behav. Anal. Pract. 2022, 15, 414–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tims, M.; Bakker, A.B.; Derks, D. Development and validation of the job crafting scale. J. Vocat. Behav. 2012, 80, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gürlek, M.; Tuna, M. Corporate social responsibility and work engagement: Evidence from the hotel industry. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2019, 31, 195–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Arnold, B. Job crafting among health care professionals: The role of work engagement. J. Nurs. Manag. 2018, 26, 321–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roczniewska, M.; Bakker, A.B. Burnout and self-regulation failure: A diary study of self- undermining and job crafting among nurses. J. Adv. Nurs. 2021, 7, 3424–3435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez, L.C.; Dolmans, D.; Restrepo, J.; Grave, W.; Sanabria, A.; Stassen, L. How Surgical Leaders Transform Their Residents to Craft Their Jobs: Surgeons’ Perspective. J. Surg. Res. 2021, 265, 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihalache, M.; Mihalache, O.R. How workplace support for the COVID-19 pandemic and personality traits affect changes in employees’ affective commitment to the organization and job-related well-being. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2022, 61, 295–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, C.; Tang, D.Y. The value of employee satisfaction in disastrous times: Evidence from COVID-19. Rev. Financ. 2023, 27, 1027–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boehnlein, P.; Baum, M. Does job crafting always lead to employee well-being and performance? Meta-analytical evidence on the moderating role of societal culture. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2022, 33, 647–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leana, C.; Appelbaum, E.; Shevchuk, I. Work process and quality of care in early childhood education: The role of job crafting. Acad. Manag. J. 2019, 52, 1169–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.E. Job crafting to innovative and extra-role behaviors: A serial mediation through fit perceptions and work engagement. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 106, 32–38. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon, H.J.; Demerouti, E.; Le Blanc, P.M.; Bakker, A.B.; Bipp, T.; Verhagen, M.A. Individual job redesign: Job crafting interventions in healthcare. J. Vocat. Behav. 2022, 104, 98–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tims, M.; Bakker, A.B.; Derks, D. Job crafting and job performance: A longitudinal study. Eur. J. Work. Organ. Psychol. 2015, 24, 914–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Wingerden, J.; Derks, D.; Bakker, A.B. The impact of personal resources and job crafting interventions on work engagement and performance. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2017, 56, 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devotto, R.P.D.; Wechsler, S.M. Job crafting interventions: Systematic review. Trends Psychol. 2019, 27, 371–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Q.; Bai, J.; Wu, T. Should we be “challenging” employees? A study of job complexity and job crafting. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 102, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dierdorff, E.C.; Jensen, J.M. Crafting in context: Exploring when job crafting is dysfunctional for performance effectiveness. J. Appl. Psychol. 2018, 103, 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, C.Y.M.; Tims, M.; Khapova, S.N.; Beijer, S. Supervisor reactions to avoidance job crafting: The role of political skill and approach job crafting. Appl. Psychol. 2021, 70, 1209–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Lee, K.S.; Kim, S.S.; Wong, A.K.F.; Moon, H. What influences company attachment and job performance in the COVID-19 era?: Airline versus hotel employees. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2022, 44, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrzesniewski, A.; LoBuglio, N.; Dutton, J.E.; Berg, J.M. Job crafting and cultivating positive meaning and identity in work. In Advances in Positive Organizational Psychology; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Cambridge, UK, 2013; Volume 89, pp. 281–302. [Google Scholar]

- Cartigny, E.; Fletcher, D.; Coupland, C. Typologies of dual career in sport: A cluster analysis of identity and self-efficacy. J. Sport. Sci. 2021, 39, 583–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattarelli, E.; Tagliaventi, M.R. How offshore professionals’ job dissatisfaction can promote further offshoring: Organizational outcomes of job crafting. J. Manag. Stud. 2015, 52, 585–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, G.; Blake, R.S.; Goodman, D. Does turnover intention matter? Evaluating the usefulness of turnover intention rate as a predictor of actual turnover rate. Rev. Public. Pers. Adm. 2016, 36, 240–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M.E.; Whybrow, P.; Kirwan, G.; Finn, G.M. Professional identity formation within longitudinal integrated clerkships: A scoping review. Med. Educ. 2021, 55, 912–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, M.; Zacher, H. Why and when does voice lead to increased job engagement? The role of perceived voice appreciation and emotional stability. J. Vocat. Behav. 2022, 132, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thevanes, N.; Baskar, T. Impact of Job Crafting on Employee Engagement in the Selected Commercial Banks in Sri Lanka. Int. J. Art. Comm. 2020, 9, 30–43. [Google Scholar]

- Tcharmtchi, M.H.; Kumar, S.; Rama, J. Job characteristics that enrich clinician-educators’ career: A theory-informed exploratory survey. Med. Educ. Online. 2023, 28, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B.; Salanova, M. The measurement of work engagement with a short questionnaire: A cross-national study. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2006, 66, 701–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olugbade, O.A.; Karatepe, O.M. Stressors, work engagement and their effects on hotel employee outcomes. Serv. Ind. J. 2019, 39, 279–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labrague, L.J.; Nwafor, C.E.; Tsaras, K. Influence of toxic and transformational leadership practices on nurses’ job satisfaction, job stress, absenteeism and turnover intention: A cross-sectional study. J. Nurs. Manage. 2020, 28, 1104–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bothma, C.F.; Roodt, G. The validation of the turnover intention scale. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2013, 11, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.C.; Yi, O. Hotel employee job crafting, burnout, and satisfaction: The moderating role of perceived organizational support. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 72, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, K.; Hean, S.; Sturgis, P.; Clark, J.M. Investigating the factors influencing professional identity of first-year health and social care students. Learn. Health Soc. Care 2006, 5, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, H.W.; Muthén, B.; Asparouhov, T.; Lüdtke, O.; Robitzsch, A.; Morin, A.J.; Trautwein, U. Exploratory structural equation modeling, integrating CFA and EFA: Application to students’ evaluations of university teaching. Struct. Equ. Model. 2009, 16, 439–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montserrat, Y.; Romeo, M.; Westerberg, K.; Nordin, M. Job crafting, employee well-being, and quality of care. West. J. Nurs. Res. 2018, 40, 52–66. [Google Scholar]

- Dash, S.S.; Vohra, N. The leadership of the school principal: Impact on teachers’ job crafting, alienation and commitment. Manag. Res. Rev. 2019, 42, 352–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatepe, O.M.; Kim, T.T. Job crafting and critical work-related performance outcomes among cabin attendants: Sequential mediation impacts of calling orientation and work engagement. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2023, 45, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tims, M.; Twemlow, M.; Fong, C.Y. A state-of-the-art overview of job-crafting research: Current trends and future research directions. Career Dev. Int. 2022, 27, 54–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philip, J. A multi-study approach to examine the interplay of proactive personality and political skill in job crafting. J. Manag. Organ. 2023, 29, 207–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, C.; Wall, P.; Batt, S.; Bennett, R. Understanding perceptions of nursing professional identity in students entering an Australian undergraduate nursing degree. Nurse. Educ. Pract. 2018, 32, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De, L.T.; Tims, M.; Bakker, A.B. Job crafting and its impact on work engagement and job satisfaction in mining and manufacturing. S. Afr. J. Econ. Manag. Sci. 2016, 19, 400–412. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, M.; Kim, B. Effects of ESG Activity Recognition Factors on Innovative Organization Culture, Job Crafting, and Job Performance. Adm. Sci. 2023, 12, 127–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.Y.; Rocco, T.S.; Shuck, B. What is a resource: Toward a taxonomy of resources for employee engagement. Hum. Resour. Dev. Rev. 2020, 19, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wu, X. Factor Analysis and Mental Health Prevention of Employee Turnover under the Profit-Centered Development of Modern Service Industry. Occup. Ther. Int. 2022, 10, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Construct | Items | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Job Crafting | Increasing structural work resources | Leana et al. [22] |

| IS1. I concentrate on improving my study and professional skills. | ||

| IS2. I often try to become more professional in my hotel work. | ||

| IS3. I try to learn new things about job. | ||

| IS4. I will try my best to complete the tasks assigned by the hotel leaders. | ||

| IS5. At work, I will think independently to complete a thing. | ||

| Increasing social work resources | ||

| IR1. I asked my supervisor to guide me. | ||

| IR2. I asked my employer if he was pleased with my performance. | ||

| IR3. I turn to my mentor for inspiration. | ||

| IR4. I’m open to receiving input on my performance at work. | ||

| IR5. I consult with my coworkers for guidance. | ||

| Increasing challenging work demands | ||

| ID1. I will actively offer to join any activity I am interested in. | ||

| ID2. I’m usually one of the first to try something new. | ||

| ID3. The off-season of the hotel should actively prepare for the next peak season. | ||

| ID4. I often take on extra tasks even if I don’t get extra pay. | ||

| ID5. I try to seek more challenges in my work. | ||

| Reducing obstructive work demands | ||

| RD1. I try to reduce the psychological stress of my job. | ||

| RD2. I’m always looking for ways to lessen the stress I feel at work. | ||

| RD3. I avoid interacting with folks who are prone to emotional outbursts. | ||

| RD4. I try to avoid folks with unreasonable expectations. | ||

| RD5. I try to avoid making difficult hotel decisions. | ||

| RD6. I would avoid putting myself in a stressful state for a long time. | ||

| Career Identity | CI1. I’m proud to say that I’m now officially a part of this industry. | Adams et al. [45] |

| CI2. I have a close bond with those who work in the hotel industry. | ||

| CI3. I’m embarrassed to say I’m studying for a hotel job. | ||

| CI4. I find myself making excuses for being a hotel employee. | ||

| CI5. I try to hide that I am learning to be part of the profession. | ||

| CI6. I’m happy to be a hotel employee. | ||

| CI7. I feel a strong connection to those who work in the hospitality industry. | ||

| CI8. Being a hotel employee is very important to me. | ||

| CI9. I feel I have something in common with the rest of the hotel employee. | ||

| Job Engagement | JE1. Whenever I’m at work, I’m bubbling with enthusiasm. | Schaufeli et al. [40] |

| JE2. My work is one that I enjoy very much. | ||

| JE3. I’m motivated by my work. | ||

| JE4. I’m eager to get to work every morning when I wake up. | ||

| JE5. When I’m working hard, I’m in a good mood. | ||

| JE6. As a professional, I take great pride in my job. | ||

| JE7. I immersed myself in my work. | ||

| Turnover Intention | TI1. I plan to get another career. | Bothma and Roodt [43] |

| TI2. I’m always mulling about the idea of quitting my present employment. | ||

| TI3. I intend to resign from my position. |

| Categories | The First Questionnaire Stage (n = 831) | The Second Questionnaire Stage (n = 622) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Percentage (%) | Number | Percentage (%) | |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 318 | 38.3 | 245 | 39.4 |

| Female | 513 | 61.7 | 377 | 60.6 |

| Age | ||||

| 18–25 (inclusive) years old | 253 | 30.4 | 154 | 24.8 |

| 25–35 (inclusive) years old | 294 | 35.4 | 197 | 31.7 |

| 35–45 (inclusive) years old | 200 | 24.1 | 160 | 25.7 |

| 45–55 (inclusive) years old | 80 | 9.6 | 88 | 14.1 |

| 55–65 (inclusive) years old | 4 | 0.5 | 23 | 3.7 |

| Marriage | ||||

| Unmarried | 361 | 43.5 | 222 | 35.7 |

| Married | 453 | 54.5 | 366 | 58.8 |

| Other | 17 | 2.0 | 34 | 5.5 |

| Education | ||||

| High school and below | 138 | 16.6 | 117 | 18.8 |

| 2-year college degree | 331 | 39.8 | 239 | 38.4 |

| Bachelor degree | 323 | 38.9 | 226 | 36.3 |

| Master degree or above | 39 | 4.7 | 40 | 6.4 |

| Department | ||||

| Front desk | 251 | 30.2 | 174 | 28 |

| Food and beverage department | 327 | 39.4 | 221 | 35.5 |

| Finance department | 67 | 8.1 | 63 | 10.1 |

| Sales department | 60 | 7.2 | 56 | 9 |

| Human resources department | 49 | 5.9 | 40 | 6.4 |

| Engineering department | 34 | 4.1 | 28 | 4.5 |

| Executive office | 26 | 3.1 | 25 | 4 |

| Other | 17 | 2.0 | 15 | 2.4 |

| Income | ||||

| <2000 CNY | 90 | 10.8 | 71 | 11.4 |

| 2000–4000 (inclusive) CNY | 372 | 44.8 | 273 | 43.9 |

| 4000–6000 (inclusive) CNY | 222 | 26.7 | 133 | 21.4 |

| 6000–8000 (inclusive) CNY | 71 | 8.5 | 62 | 10 |

| 8000–10,000 (inclusive) CNY | 44 | 5.3 | 53 | 8.5 |

| >10,000 CNY | 32 | 3.9 | 30 | 4.8 |

| Position | ||||

| Intern | 118 | 14.2 | 88 | 14.1 |

| Ordinary employee | 369 | 44.4 | 243 | 39.1 |

| Foreman, supervisor | 155 | 18.7 | 121 | 19.5 |

| Department manager | 81 | 9.7 | 70 | 11.3 |

| Director, general Manager | 67 | 8.1 | 67 | 10.8 |

| Other | 41 | 4.9 | 33 | 5.3 |

| Years of work in the industry | ||||

| ≤1 year | 223 | 26.8 | 166 | 26.7 |

| 1–3 (included) years | 275 | 33.1 | 175 | 28.1 |

| 3–6 (included) years | 178 | 21.4 | 136 | 21.9 |

| 6–10 (included) years | 96 | 11.6 | 91 | 14.6 |

| >10 years | 59 | 7.1 | 54 | 8.7 |

| Dimension and Item Description | Factor Loading | Cronbach’s α | % of Variance | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reducing obstructive work demands (RD) | 0.918 | 21.352% | |||

| RD4 | 0.862 | 3.44 | 1.026 | ||

| RD5 | 0.851 | 3.46 | 1.058 | ||

| RD3 | 0.848 | 3.44 | 1.058 | ||

| RD2 | 0.831 | 3.55 | 1.043 | ||

| RD1 | 0.806 | 3.49 | 1.074 | ||

| Increasing challenging work demands (ID) | 0.889 | 38.714% | |||

| ID2 | 0.853 | 3.45 | 0.999 | ||

| ID4 | 0.848 | 3.44 | 0.995 | ||

| ID3 | 0.833 | 3.49 | 0.978 | ||

| ID5 | 0.773 | 3.52 | 0.976 | ||

| ID1 | 0.730 | 3.54 | 0.963 | ||

| Increasing social work resources (IR) | 0.884 | 55.938% | |||

| IR2 | 0.860 | 3.65 | 1.057 | ||

| IR3 | 0.855 | 3.67 | 1.100 | ||

| IR1 | 0.834 | 3.72 | 1.058 | ||

| IR4 | 0.746 | 3.44 | 0.910 | ||

| IR5 | 0.718 | 3.40 | 0.948 | ||

| Increasing structural job resources (IS) | 0.906 | 71.570% | |||

| IS2 | 0.874 | 3.45 | 0.940 | ||

| IS1 | 0.871 | 3.57 | 0.910 | ||

| IS4 | 0.860 | 3.55 | 0.936 | ||

| IS3 | 0.850 | 3.42 | 0.947 | ||

| Career identity (CI) | |||||

| CI1 | 0.913 | 3.48 | 1.034 | ||

| CI2 | 0.908 | 3.50 | 1.022 | ||

| CI3 | 0.917 | 3.43 | 1.05 | ||

| CI4 | 0.814 | 3.55 | 0.997 | ||

| CI5 | 0.608 | 3.55 | 1.027 | ||

| CI6. | 0.624 | 3.53 | 0.957 | ||

| CI7 | 0.801 | 3.37 | 0.938 | ||

| CI8. | 0.713 | 3.42 | 0.963 | ||

| CI9 | 0.624 | 3.41 | 0.975 | ||

| Job engagement (JE) | 0.938 | ||||

| JE1 | 0.834 | 3.54 | 0.914 | ||

| JE2 | 0.816 | 3.60 | 0.929 | ||

| JE3 | 0.786 | 3.61 | 0.913 | ||

| JE4 | 0.771 | 3.54 | 0.919 | ||

| JE5 | 0.826 | 3.53 | 0.929 | ||

| JE6 | 0.795 | 3.53 | 0.915 | ||

| JE7 | 0.798 | 3.54 | 0.935 | ||

| Turnover intention (TI) | 0.912 | ||||

| TI1 | 0.851 | 3.47 | 0.936 | ||

| TI2 | 0.862 | 3.51 | 0.913 | ||

| TI3 | 0.832 | 3.44 | 0.907 |

| CR | AVE | CI | JC | TI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Career identity (PI) | 0.918 | 0.651 | 0.896 | ||

| Job crafting (JC) | 0.890 | 0.619 | 0.847 | 0.801 | |

| Job engagement (JE) | 0.875 | 0.593 | 0.760 | 0.672 | |

| Turnover intention (TI) | 0.907 | 0.708 | −0.734 | −0.664 | 0.905 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xu, J.; Wang, C.; Zhang, T.; Zhu, L. How Job Crafting Affects Hotel Employees’ Turnover Intention during COVID-19: An Empirical Study from China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9468. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15129468

Xu J, Wang C, Zhang T, Zhu L. How Job Crafting Affects Hotel Employees’ Turnover Intention during COVID-19: An Empirical Study from China. Sustainability. 2023; 15(12):9468. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15129468

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Jiahui, Chaohui Wang, Tingting (Christina) Zhang, and Lei Zhu. 2023. "How Job Crafting Affects Hotel Employees’ Turnover Intention during COVID-19: An Empirical Study from China" Sustainability 15, no. 12: 9468. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15129468

APA StyleXu, J., Wang, C., Zhang, T., & Zhu, L. (2023). How Job Crafting Affects Hotel Employees’ Turnover Intention during COVID-19: An Empirical Study from China. Sustainability, 15(12), 9468. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15129468