1. Introduction

The peculiarity of consumer behavior caused by a pandemic situation is determined by the scale and pace of the changes taking place relative to the emergency. The COVID-19 pandemic radically changed the functioning of modern societies and economies. The consensus opinion among market trend researchers and analysts is that the pandemic significantly affected consumer behavior [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Moreover, consumer behavior undergoes significant changes in the face of crises and involves assessing the risks and negative consequences of specific consumer decisions [

5].

The pandemic has also dramatically changed the face of the food market in Poland. The uncertainty of the aftermath of COVID-19 has boosted the demand “for stock” and has boosted sales. In 2020, there was a 6.7% increase in grocery retail compared to the previous year [

6].

In the modern world, responsible, sustainable consumption is gaining popularity [

7,

8]. Sustainable and rational food consumption occupies a special place in the concept of sustainable consumption [

9,

10]. It is based on consumer awareness, rational choices, and reduced waste. Conscious consumption can manifest itself in various ways, but it should nevertheless be guided by the 3Rs principle: reduce, reuse, recycle.

The importance of the problem of reducing food loss and waste as a factor shaping food safety has physical, economic, social, health, environmental, and technical–technological dimensions [

11,

12]. Globally, as much as one-third of the food produced is lost annually along the food chain [

13]. In Europe, consumers are estimated to account for 22% of food loss and waste in the supply chain [

14]. Food waste at the household level is a complex behavior related to consumer decisions on food handling, such as shopping planning, storage, preparation, and consumption of food [

15,

16,

17]. These behaviors vary according to the nationality, culture, demographics, and shopping habits [

18,

19]. However, a universal consumer typology for food waste does not exist. It is not possible to create a single typology that applies universally to all consumers. However, it is feasible to develop typologies for specific social and democratic groups within a particular geographic region. There is a lack of deeper knowledge about the causes, effects, and scale of this phenomenon due to incomplete record-keeping and different ways of measuring it, as well as the possibility of preventive measures for its occurrence [

20,

21]. Moreover, if such knowledge existed, after all, the COVID-19 pandemic crisis changing societies’ value systems as well as hierarchy and daily habits [

12,

22] could also have caused an evolution in the lifestyle and consumption patterns of the population. This also applies to food stewardship and measures for assessing the rationality of food use. This justifies the need for new research at the micro level in order to determine whether the direction and degree of changes are consistent with the sustainable development paradigm. If so, it should be consolidated through the educational and institutional system [

23]. The publication of this research fulfils a condition proposed in the literature for promoting stronger cooperation and the exchange of information and experiences within the international space community. Additionally, it serves the purpose of disseminating research findings on this topic [

24].

The most dynamic subject of behavioral transformations in the economic and social sphere is young people. Young consumers constitute an important and, at the same time, separate part of every society, requiring constant exploration. This is because they are special market participants, as (unlike more mature participants) they feel needs differently, perceive the world differently, understand messages addressed to them, have different value systems, and different ways of behaving. Meanwhile, the phenomenon of adolescents’ behavior as food consumers is not fully recognized. However, we know that stress and isolation due to COVID-19 can be a factor in changing consumption patterns [

25,

26]. These young consumers play an important role in terms of the problem under study, as they reflect a significant segment of the total households and may be predictors of new food trends [

27]. The research of J. Tarapata [

28] shows that a phenomenon strongly outlined in the sphere of young people’s consumption is their high awareness of growing ecological and social problems and the dangers that result from them as well as their conviction that they can influence the improvement of the environment with their attitude and behavior.

It should be noted that the study of consumer behavior in the food management process is particularly important during epidemic crises, wars, natural disasters, and other crisis situations leading to prolonged imbalances in the economy, the market, and an increase in the threat to food security. Opportunities are then sought to reduce these imbalances in the global food market by identifying the behavior of food system actors at the micro level and identifying the necessary corrective actions at the meso and macro level “that affected food system and food governance” [

29]. The COVID-19 pandemic has caused the greatest global crisis and is a source of changes in the economic and social behavior of the consumers. It disrupted the routine consumerist activities of the population in satisfying their needs and disseminated the previously evoked reflection on the need for sustainable development and social rationality. The pandemic has caused a significant change in the awareness of societies, which should shape a new trend of consumer behavior, reflected by Consumer 4.0. This phenomenon requires confirmation by scientific research regarding the benefits and losses resulting from this process and the indication of instruments to support it in an effective way. The Consumer 4.0 model is spreading rapidly as an active subject of the fourth world industrial revolution [

30]. Its features include high awareness, permanent education, high quality requirements, reduction in food waste, orientation to ecological products, digitalness, and being conducive to the implementation of sustainable development assumptions, including the increase in the social rationality of food management. In order for this direction of change in consumer behavior to continue, strong changes in the environment are required, while also stimulating consumers to move away from negative habits [

31].

Currently, one research method on this topic is to adopt a circular economy (CE) model promoting a sustainable food system [

32,

33,

34,

35]. The role of the different actors in this system, e.g., producers, traders, processors, and consumers, is to ensure that the conditions of production, transport, storage, and distribution of food ensure its high quality and health safety [

36,

37]. However, there are barriers that inhibit the introduction of a CE [

38]. These are identified and analyzed, among others, by N. Ada et al. [

37] as cultural, business–financial, legal, technological, food chain management, and knowledge and skills. Very similar views on these barriers are formulated by G.D.A. Galvão et al. [

39] and J. Grafström and S. Asama [

40]. Therefore, the question arises about the level of intangible barriers in relation to the concept of reducing food waste. In this context, it has become important to gain knowledge about existing behavioral patterns of young consumers during the COVID-19 pandemic, in terms of food stewardship in a situation of food waste and the need to save production factors included in the FL–FW–FS (food loss–food waste–food security) and W–E–F (water–energy–food) nexus [

41].

Two assumptions are already documented in the literature. Firstly, the consumer as a subject of stewardship has an important influence not only on shaping the size and structure of the demand for food (market), but also on its use. In view of this, consumers directly influence food safety at the macro level through their behavior in the process of purchasing, purchasing and transport organization, storage, home processing, food preparation, and consumption [

42,

43]. Secondly, consumers, as decision-makers of their budget, having different preferences in the ways they meet their food needs [

44], generate different levels of waste [

45].

There is a perceived research gap in the global literature on the indirect and direct role of the consumer in shaping food security in all links of this system, understood as integrating the activities of food supply from the field to the consumer’s plate [

46].

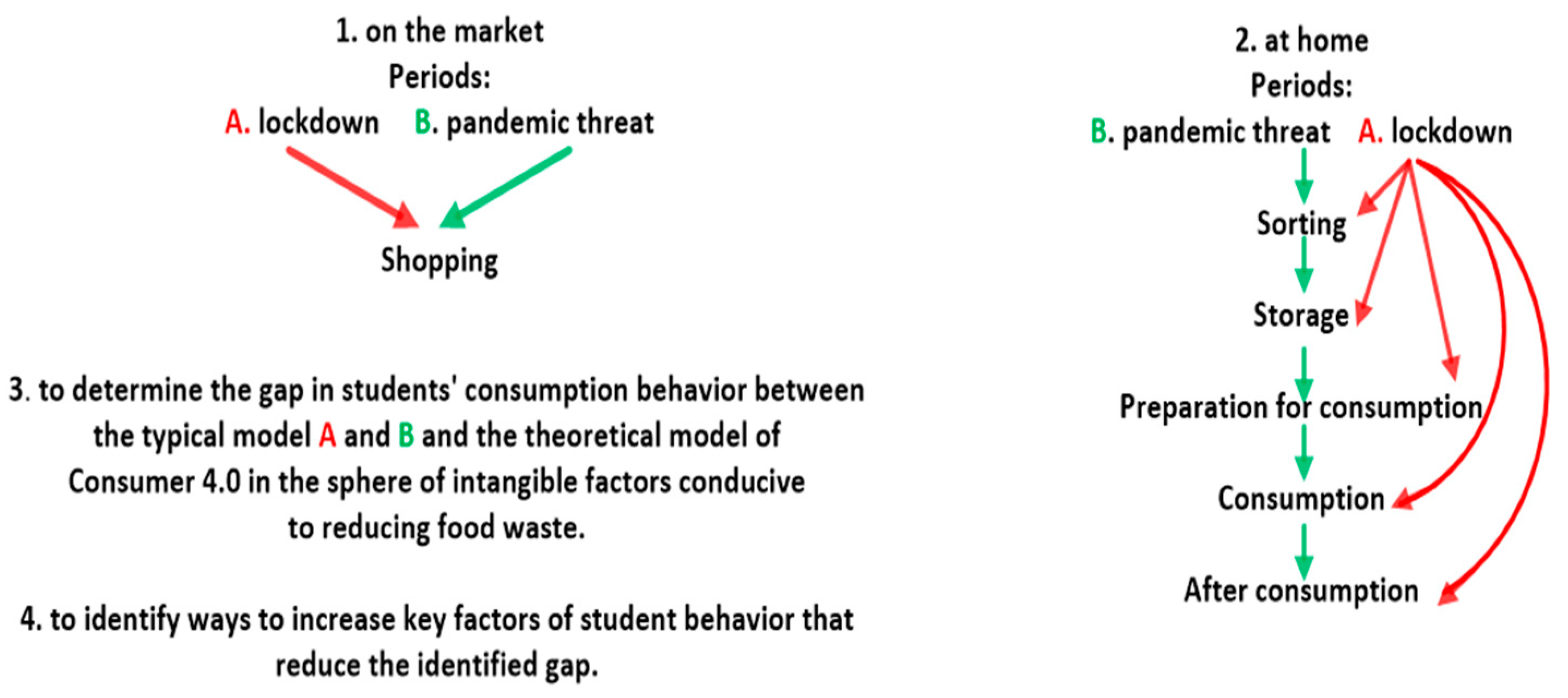

The research problem of this paper is to identify differences in students’ consumer behaviors in terms of food saving, and thus food creation resources, during the two periods of the COVID-19 pandemic, i.e., during lockdown and during the pandemic emergency. At the core of this problem are two questions: did the behavior of university students at the market and in their households, during the COVID-19 pandemic, promote food frugality by reducing food waste? Additionally, what factors created food waste?

Let us note that the young consumer, as the decision-maker of his or her budget, can choose one of two paths in the process of meeting food needs. The first, by adopting a direct and independent preoccupation with the satisfaction of his/her consumption needs. This includes purchasing preferences expressed in the market, transport, storage, and preparation of products for consumption at home as well as consumption and waste reduction. The second pathway is the indirect engagement in meeting one’s needs through the purchase of ready meals in restaurants, bars and canteens, pubs, etc. In each pathway of choice, waste can occur. It therefore becomes important to know the empirical model of students’ consumer behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The cognitive purpose of this study is to examine the reduction in food waste by students in the economic process during the lockdown, in the context of the Consumer 4.0 model. The applied objective is to identify the determinants of increasing the social rationality of ex ante food stewardship by university students’ food waste reduction.

This article is carried out within the framework of experimental economics and is in line with the trend of sustainability economics and economics of moderation, exposing the importance of qualitative analyses. The novelty of the experimental research in this study is (1) the use of a comparative method for the lockdown period, reflecting the consumer behavior of young people in reducing food waste and (2) the use of the model method in determining the factor gap between the theoretical model of Consumer 4.0 and a typical model of behavior of students, in search of reasons for the lack of significant changes in these behaviors in reducing waste after the lockdown was lifted. The application meaning consists of defining the instruments and methods of reducing and overcoming the identified factor distance, necessary to accelerate changes at the micro, meso, and macro levels in the implementation of sustainable development in Poland.

2. Materials and Method

The ambiguous approach in the literature to concepts relevant to the research topic undertaken necessitates the definition of the authors’ position on some of them in this paper. These are food waste and loss, sustainable consumption, Consumer 4.0, and the social rationality of consumer behavior in food stewardship.

The interpretation of the first two categories, which are often wrongly considered together in relation to consumers and households, follows the FAO. It defines losses as the total of edible products of plant and animal origin along the food chain from product sourcing (production) up to, but not including, retail [

14,

47,

48]. This includes natural losses of total weight, food discarded, burnt and removed from the food supply chain and for other purposes (feed, biofuels), and the deterioration of its quality (nutritional composition) during transport and storage. Wastage, on the other hand, according to the FAO, should be referred to the socially irrational management of food at retail and in households and collective consumption entities [

48,

49,

50]. It takes the form of food rejection due to the shelf life, size, shape, color, appearance, smell, or form of leftover unconsumed food. There may also be a deterioration in food quality in these links in the food chain, in cases of poor storage or inappropriate cooking. In addition, when purchasing, consumers generally do not control what they purchase and do not have full knowledge of the food they buy in the market [

49]. Therefore, it may occur that some of it is thrown away at home due to undesirable ingredients in it, shelf life, bad smell, taste, or other organoleptic characteristics. In view of the above, in the process of food stewardship by students, there is food waste in terms of quantity and quality, and this phenomenon is the subject of this paper.

Another economic concept that needs to be clarified by the authors in its interpretation is sustainable consumption [

28]. According to the concept of sustainable development, there is consumer participation in shaping sustainable consumption [

51]. This concept includes action for future generations by reducing food waste and loss [

52,

53] using closed-loop food management principles [

54]. The implementation of the doctrine of sustainable consumption requires society to give up overindulgence because “sustainable food consumption protects, respects biodiversity and ecosystems, is culturally acceptable, accessible and equitable” and it is a “prevention of diseases of civilization resulting from overconsumption and obesity” [

55]. There is a reference to the EU’s “green economy” concept [

56], which exposes biodiversity and landscape biodiversity in sustainable consumption and production [

57,

58]. An expression of strong sustainable consumption is the increasingly emerging consumer attitudes and behaviors manifested in the pursuit of moderation in the acquisition of new goods and the search for and consumption of products that do not damage the environment. This trend is characterized by rational choices aimed at achieving consumer sustainability and achieving sustainable development goals.

The concept of Consumer 4.0 is related to the industrial market, high-tech products, and new IT and digital services. In the literature, it is defined by the following features: digitality, high awareness, convenience, individualization, permanent education, the search for new knowledge, and high quality requirements. With regard to the food market, we add the following features: reducing food waste, saving food, focusing on innovative ecological products, and deconsumption [

59,

60,

61,

62,

63]. Consumer 4.0 recognizes the need and accepts the drive to optimize processes through the use of the Internet of Things. At the same time, he or she is accompanied by concerns about the quality of a product with which he or she does not have direct contact during the transaction [

64]. Therefore, he or she prefers local products and personalized sales offers and looks for a value with which he or she identifies [

65], e.g., organic product branding. In addition, Consumer 4.0 expects retailers or producers to build a relationship with him or her and to maintain continuous communication with him or her, facilitating the purchasing process with ongoing or temporary advice.

In the process of purchasing food products, we are confronted with the notion of the rationality of consumer decisions relating to the possibility of alternative choices of needs and the way in which these needs are satisfied, which involves the processing of information in this respect. The degree of rationality of individual consumer decisions varies, as do the motives that drive them. The rational behavior (conduct) of the consumer in purchasing food in the neoclassical paradigm meant that individuals in society, in the process of satisfying needs, maximize expected utility. This view has been challenged by other currents in economics (e.g., new classical economics, complexity economics, or behavioral economics).

In the 21st century, the rationale for redefining the neoclassical approach to the rationality of consumer behavior in the economic process in general has been presented in a number of works [

66,

67]. The knowledge that a person possesses forms the basis for choosing ways to individually satisfy his or her needs, according to his or her own system of values and preferences [

68]. During this choice, there are emotions that interfere with the “process of perception and logical inference”, and there are different activities of individuals in the search for information and its processing, which leads people with a low evaluation of these activities to irrational decisions [

69]. The next determinant of the degree of rationality of consumer behavior, besides knowledge, is the ability to perceive reality, as well as the social contexts, namely the formal and informal institutional system. The consumer’s behavior can be considered as socially rational if his or her individual actions are not based on selfishness and waste but aim to improve the quality of life of present and future generations [

66]. Such a goal is adopted in the circular economy model, in which the role of the consumer is clearly defined. The number of consumers fulfilling the criterion of social rationality increases as awareness grows, leading to a shift from the ideology of consumerism and hedonistic attitudes to consumption of moderation [

70,

71,

72]. The social criteria of rationality assessments are related to the impact of food needs satisfaction processes on the level of human health, consumer groups, and society as a whole. At this level, measurement is complex. When considering and assessing the consumer’s behavior in this sphere from a social perspective, it is necessary to take into account the manifestations of his or her pro-environmental behavior (donating excess food, segregating waste, using natural resources sparingly). It is also important to assess the consumer’s desire to learn more and become more active in the undertaking to protect the environment.

Theories of consumer needs and behaviors are in constant development. Therefore, in this study, the rationality of young consumers’ behavior is defined not only for the entire economic process, but also for each phase of the decision-making process.

The diverse nature of food needs, the increasing role of social factors in their determination, the differentiated behavior of consumers satisfying this group of needs, determine the complexity and multifaceted nature of the concept of rationality of consumption and consumer behavior in the sphere of food consumption. Sustainable consumer behavior in the sphere of food consumption should be considered as consumer behavior that leads to the satisfaction of food needs at a level that allows for the proper functioning and development of the organism and ensures a satisfactory quality of life in this sphere, while at the same time minimizes the consumption of natural resources and materials harmful to the environment as well as takes into account the well-being of other people [

9].

In the implementation of the cognitive objective of the study formulated in the introduction, the main research hypothesis was generated as follows: In the behavior of students in the process of food stewardship during lockdown, there were behaviors less conducive to food saving than during the pandemic threat. The identification of five specific hypotheses was helpful in its verification. In turn, a sixth hypothesis was set in the execution of the normative objective. All hypotheses were subject to the procedure of testing during the analysis. They are as follows:

H1. Students’ decisions regarding quantitative–structural and frequency to purchase food products at the market during lockdown (S1) generated greater wastage than during pandemic risk (S2).

H2. At the stage of ready-food purchase and consumption, students behave less wastefully during lockdown than during pandemic threat.

H3. The level of food loss during food storage is higher during lockdown.

H4. Students’ behavior regarding the reduction in food waste in the household showed no significant differences between the two periods studied.

H5. Disciplinary actions in the students’ household regarding the reduction in food waste represent a weaker food saving behavior in period S1 than S2.

H6. There is a gap between the students’ typical behavior model and the Consumer 4.0 model reflected in their internal factors in food stewardship on the paradigm of sustainable development.

Several scientific methods were used to test the above hypotheses and perform the objectives of the article. First of all, the method of a deep literature study, description, and induction was used. In the experimental part, the following methods were used: questionnaire, comparative, model, and deduction methods. The method of descriptive statistics was used in the elaboration of the primary data, representing the responses to the survey questionnaires.

The methodology in the empirical part of the study included:

Selection of the sample population;

Preparation of operational tools to assess wastage;

Ensuring comparability of results.

Re 1. The subjects of the research, constituting the general population, were students of the Faculty of Economics and Management at the University of Zielona Góra. Their selection for the survey was purposive–voluntary. The non-random selection of individuals, allowing for inferences about the surveyed population on the basis of the results from the sample, was possible due to the extensive experience and knowledge of the researchers, as well as their great intuition. An indirect diagnostic survey method was used. The responses obtained are representative of the total student population of this faculty.

The time range of the empirical research covered the period from March 2020 to June 2022. At that time, a state of epidemic and epidemiological threat was announced in Poland covering four periods of lockdown, i.e., (1) 24 March 2020–30 May 2020, (2) 17 October 2020–29 November 2020, (3) 28 December 2020–17 January 2021, and (4) 20 March 2021–9 April 2021 [

73,

74,

75,

76,

77].

The survey was carried out among respondents who were full-time students (pursuing bachelor’s or master’s degrees in economics, management, logistics, and security) and had passed a micro- and macroeconomics course at least at an intermediate level. The survey was conducted May–June 2022. The question form was available online during the period for the entire student population of 690. A total of 176 respondents completed the survey questionnaire and, after the validation of the answers, a final sample of 167 questionnaires (approximately 24%) met the conditions for further analysis, ensuring the reliability of the results.

Re 2. The research tool for obtaining the primary data that was prepared for the sample population was a survey questionnaire, which was uploaded to Google and then made available to the students. The use of the CAWI method was determined by the possibility to implement it in lectures and exercises and to control the course, while ensuring the anonymity of the students completing the questionnaire. This research instrument consisted, in addition to a metric (9 questions), of 4 substantive parts comprising 42 questions, including 34 closed questions with an extended number of response options and 8 semi-open questions (with a semi-open answer area). They were logically structured into four groups, corresponding to the stages of household food stewardship. These groups were 1. purchase of food products vs. food waste; 2. purchase and consumption of prepared meals vs. food waste; 3. food storage in the student’s household; 4. assessment of causal factors for reducing food waste in the household, at the pre-, during, and post-consumption stages. The responses to the respondents’ survey questions were qualitative in nature, so nominal and ordinal measurement scales were used in their assessment.

Re 3. To ensure the comparability of the results, the model method was applied. A model is a representation of real phenomena in a simplified way [

78] and “it reflects the most essential elements of reality and the relations between them” [

79]. This paper presents a theoretical model of Consumer 4.0 in food stewardship and a typical model of student behavior as a consumer (

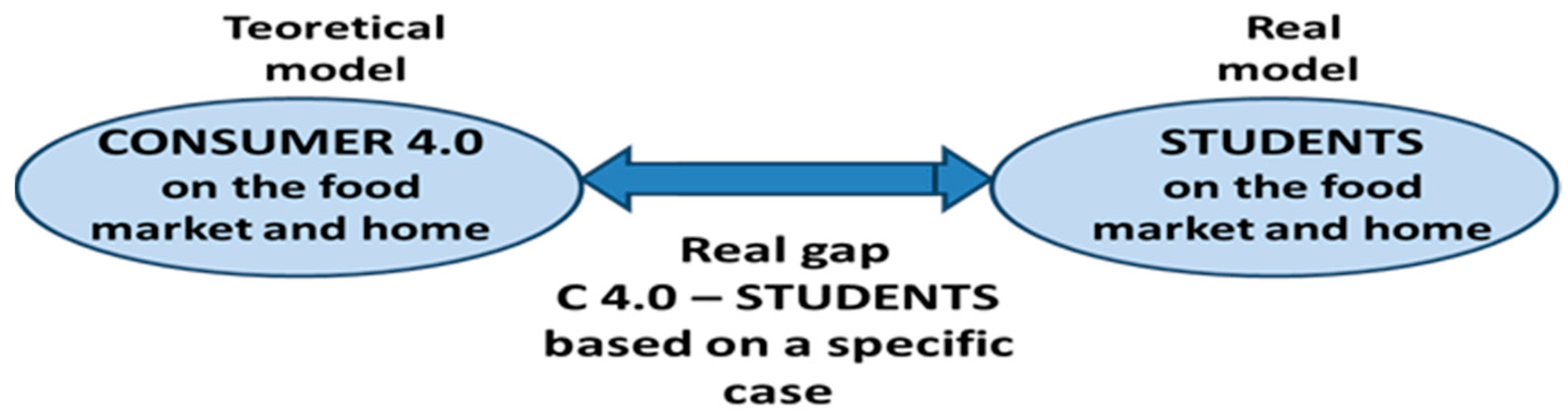

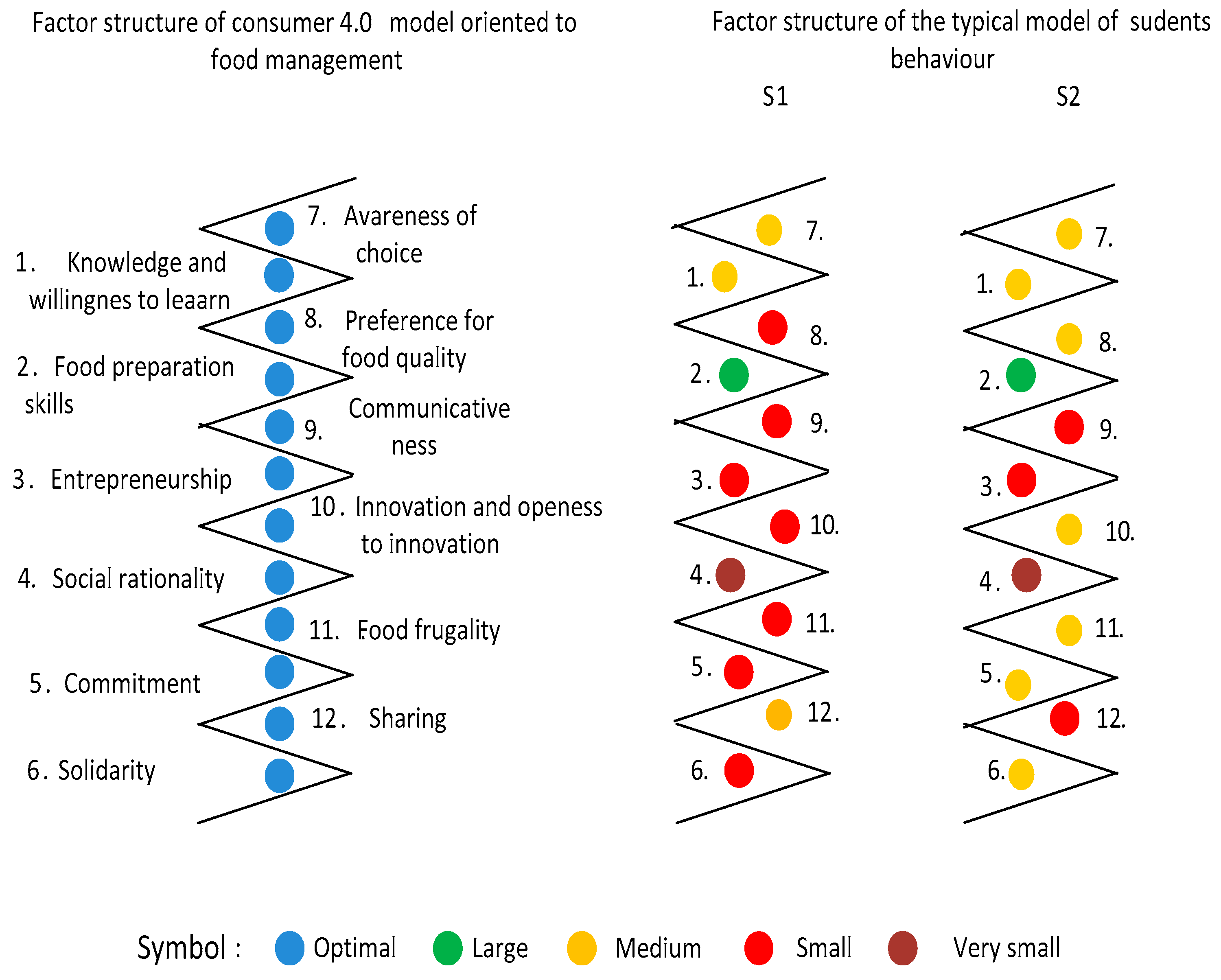

Figure 1). The models are in drawing and descriptive form. The construction of the theoretical model uses the method of deduction and the second one the method of induction. They serve to reflect the actual gap in consumer behavior separately in each of the two studied periods, i.e., lockdown (S1) and epidemic risk (S2).

The constituent factors of the theoretical model of Consumer 4.0 minus the constituent factors of the typical model pattern from the empirical research equals the gap of internal factors that influenced the reflected food management behavior of students in the periods studied.

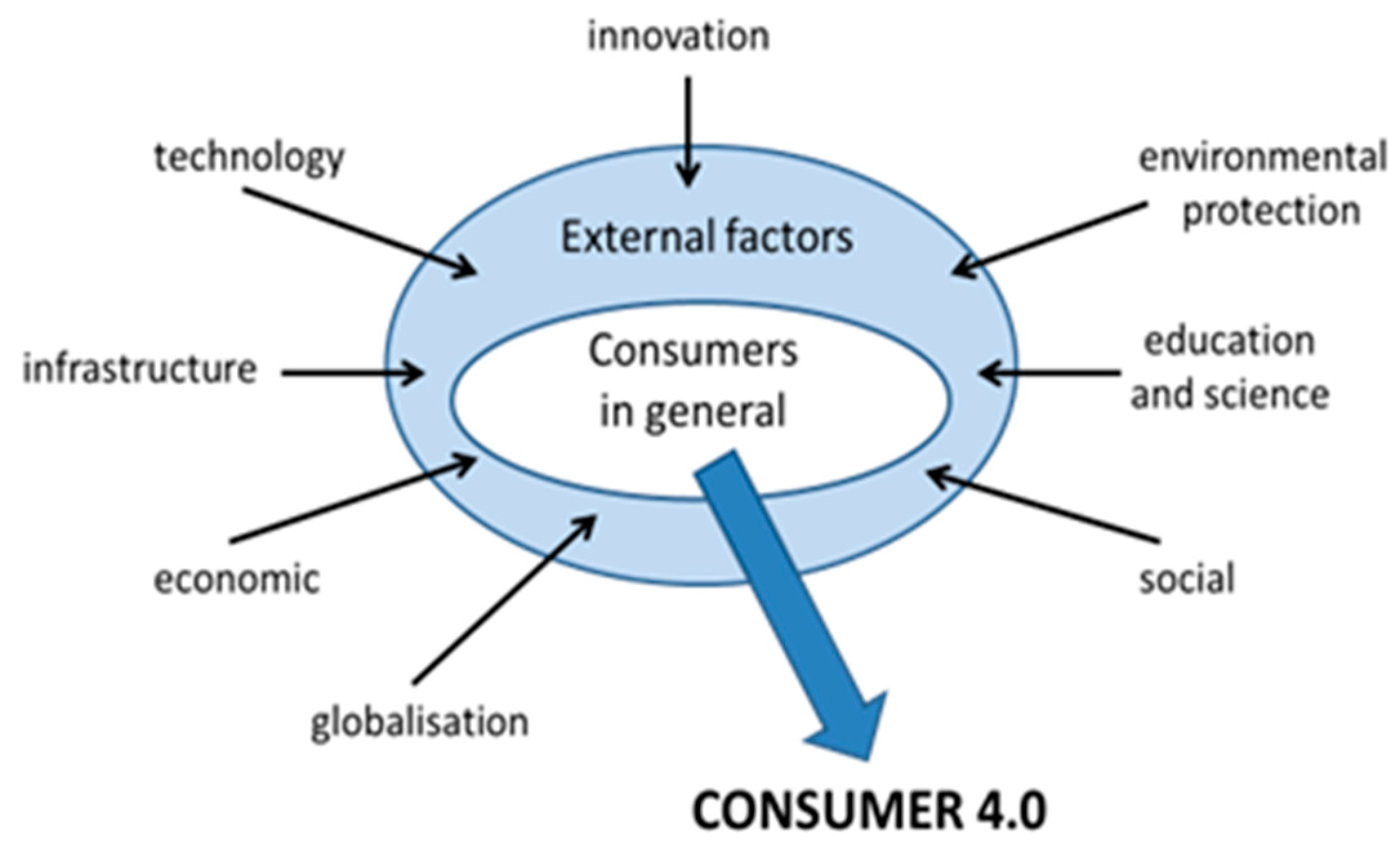

Turning to the construction of the theoretical model, let us note that Consumer 4.0 in the third decade of the 21st century must present a particular set of internal characteristics, and above all a high sensitivity to sustainable consumption, social rationality, and quality of life issues. The path of its emergence from the total stock of consumers is influenced first by the external factors highlighted in

Figure 2 and then by the stock of internal factors. These can accelerate the process or delay it. The resources of human and social capital, which are internal factors of the total consumer stock, can be conducive to this process when their quality, measured by the level and structure of attributes, is high. It follows that not everyone will meet the conditions of Consumer 4.0. There will first appear certain groups of buyers setting the trend for the formation of this consumer’s behavior.

Listed below are those external and internal factors that are important on the path leading to the formation of Consumer 4.0 in socially rational food management. External factors—the meso and macro environment influencing the behavior of the general consumer—are in the groups of economic, technological, legal, social, political, environmental, and cultural factors. These include the following:

Technological development of the region;

Innovation of economic entities;

Instrumental support of infrastructure development;

Level of economic development (income per capita, rate of economic activation of the population);

Active social policy of the state, health, and environmental protection;

Education and science policy;

Globalization and internationalization;

Level of cultural development;

Institutional support for sustainable development policies.

The internal factors of the general consumers form the attributes of human capital, i.e., knowledge and skills as well as social capital. It is worth noting that, in the discussion on social capital in the context of consumer behavior, the authors take the position that social capital is part of the resource theory [

80,

81], namely, relational [

82,

83] and litigious [

84]. Representatives of the first perspective distinguish individual resources and attributes of social capital. These are trust, awareness of social limitations, entrepreneurship, responsibility, values, openness, communicativeness, innovation, and creativity.

With a general overview of the causal factors of consumer behavior, it is possible to construct, using the method of deduction, a theoretical model of the structure of the internal factors of Consumer 4.0 regarding food stewardship. In order to do so, it is necessary to single out those that are directly related to the new paradigm of economic–social–environmental sustainability of the entire economy in the third decade of the 21st century. This is the smart consumer. The following are key internal factors of strategic importance for its behavior when assumed as optimal in the theoretical model:

Deconsumption;

High knowledge;

Permanent learning about healthy eating;

Openness to innovation;

Consideration of environmental aspects in purchasing decisions;

Awareness of environmental constraints;

Image of a socially rational person;

Values toward resource conservation and ecology;

Preference for quality products and pro-healthy lifestyles;

Saving food by reducing food waste;

Solidarity and discipline in activities for the common good;

Sharing of food products;

Digitalization in communication in the food management process.

The next step in the analysis was to determine the gap (distance) between the objects being compared, i.e., the theoretical model and the typical, empirical model, in order to identify those factors that represent weaknesses in the transition to the formation of Consumer 4.0 with regard to food saving. Therefore, it is important to analyze the respondents’ answers about food waste in the different links of food management and the sources of this phenomenon. This will become necessary to determine a model of typical student consumer behavior (

Figure 3).

The experimental study was not exhaustive, but the sample size is representative of the total population and was sufficient to verify the generated hypotheses and the formulated objectives of the study. Nevertheless, the extrapolation of conclusions from the analysis regarding consumer behavior in saving food has some limitations. As D. Desjeux [

85] points out, “The causes explaining actors’ behavior vary based on the scale of observation […] All generalizations are thus limited to scales pertaining to the same type of causality. […] The variability of causes determines human behavior” [

85]. In the case of this work, the cause of the changes in consumer behavior was the COVID-19 pandemic and the related lockdown. It was made in mid-2022, after the lockdown was lifted. However, this cause may soon repeat itself. Therefore, the inference can be generalized to the entire population and not only to a specific socio-demographic group in Poland, which this analysis undertakes. The dissemination of conclusions is also possible thanks to the Consumer 4.0 model adopted in this work, focused on the implementation of the assumptions of sustainable development, in which all members of society, regardless of age, gender, and education, are included in the creation process. A certain limitation to the research and conclusions is the fact that the construction of the questions in the survey was of a qualitative nature. Attitudes, behaviors, and consumer opinions of students were assessed. However, the lack of quantitative questions may limit the perspective, but not the depth, of reasoning.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Food Purchase and Food Wastage

The first part of the survey questionnaire contains 12 questions (P) relating to students’ behavior in the market. First of all, they were asked how they made their purchases: directly (in person) or indirectly (Internet). Of the 167 respondents, as many as 153 (91.1%) stated that they directly shop themselves. Only 14 (8.9%) respondents made their purchases on the Internet or used the help of family or friends.

In Poland, in April 2020, online food sales increased by nearly 100% from month to month. Nonetheless, this meant barely exceeding the one-process threshold for the share of online sales in total food retail sales. According to research conducted by the global, independent audit and advisory firm KPMG [

86], among Polish consumers during the pandemic period, the frequency of online food purchases increased by 22%, the highest increase among all other shopping categories. The largest group of people (43%) who reduced their visits to stationary shops for grocery shopping as a result of the pandemic were customers aged 25–39. In contrast, research by P. Chlipała and A. Żbikowska [

87] shows that in Poland, a small proportion of consumers, during the COVID-19 pandemic, bought food online, while a significant group of consumers (over 40%) sourced their groceries from shops near their place of residence. In addition, the frequency of grocery shopping increased during this period. Changes in the way in which food purchases are made distinguish Polish consumers from buyers in other countries. For example, in China, the percentage of consumers buying food in local shops increased slightly, while it decreased significantly (by almost 20%) in supermarkets located in the immediate vicinity [

88].

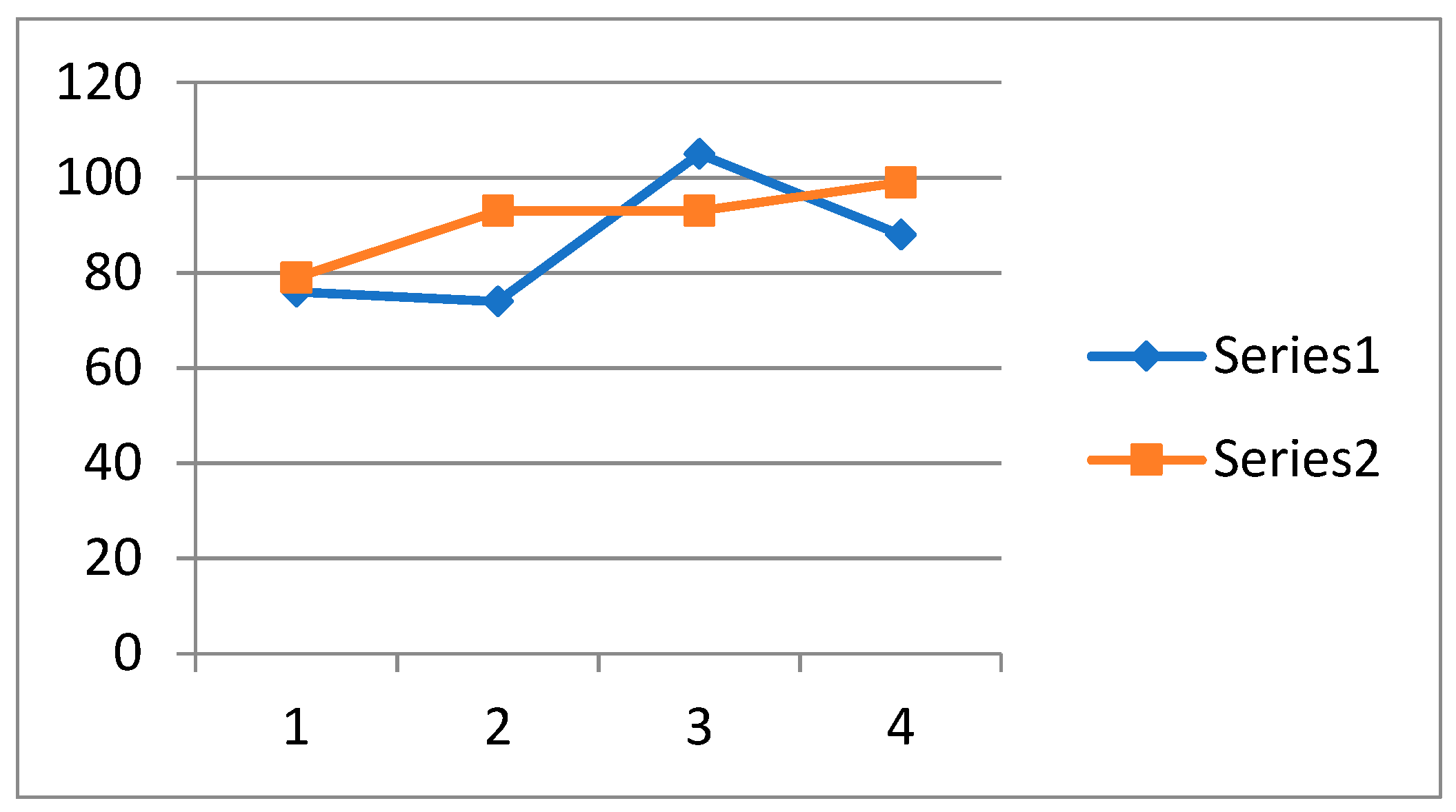

The next two questions relate to the frequency of purchases separately for the lockdown period (P2) and for the pandemic risk period (P3). The same four options of indications were available to choose from in both questions. The responses obtained are shown in

Figure 4.

The frequency of the purchases indirectly affects food waste when they are too scarce. Consumer behavior should be considered rationally justified. Food shopping, depending on the type of food, occurs with different frequencies. In the lockdown period (S1), young consumers preferred less frequent purchases, i.e., once every two days or even every week, which was logical due to the contact reduction policies. In contrast, during the pandemic risk period (S2), food purchases with a frequency of every 2 days were most prevalent. Only five students indicated that they bought food once a month. Meanwhile, twice as many did during S1. It must also be taken into account that food varies greatly in terms of shelf life. Since the question is about foods with different shelf lives, the number of answers exceeds the number of people taking the survey.

Research conducted by V. Borsellino et al. [

89] on the impact of the coronavirus pandemic on food purchasing behavior showed that, during the initial period of the pandemic, increased shopping and stockpiling due to fear and uncertainty were characteristic of most consumers. After “getting used to” the situation, purchasing habits became largely diverse and determined by attitudes toward COVID-19, personal experiences, economic status, and many other factors. In parallel with the pandemic, there was an increased interest in home cooking, buying from local suppliers, purchasing food online, as well as purchasing healthy food (despite concerns about future income) and reducing waste.

The respondents gave a very similar response to the next two questions, regarding shopping patterns during the periods studied, answering the options (1) conscious, (2) hasty, or (3) occasional. The responses for both periods were similar. Only slightly fewer people thought about and purchased food products consciously (5% of students) during the pandemic risk period (S2) than in lockdown (S1). The next two questions were designed to explore students’ purchasing preferences during periods (S1) and (S2) toward products in the following choice options: (1) traditional and familiar, (2) innovative (new), (3) high quality, or (4) organic and health-promoting (

Figure 5). The respondents’ answers indicated 95.6% for traditional products in period S1 and decrease to 94.6% in period S2.

The above questions were multiple choice. The answers show that almost all respondents in both survey periods S1 and S2 indicated traditional and familiar products, while almost half of them indicated trust in the brand, quality, and origin. There was less interest in innovative products or those with organic properties. However, it is important to emphasize that, in both cases, the interest in these products increased markedly by several tens of percentage during the pandemic threat period. Thus, in both periods, traditional foods (1) lead the way, ahead of those that inspired confidence due to brand and quality aspects (3). The other two categories (2 and 4) have similar shares at noticeably lower levels in both periods. However, demand for items 2, 3, and 4 increased in the post-lockdown period.

Deepening the analysis of the data, it was taken into account that consumers purchase a variety of foods when meeting their needs. Therefore, the following figures (

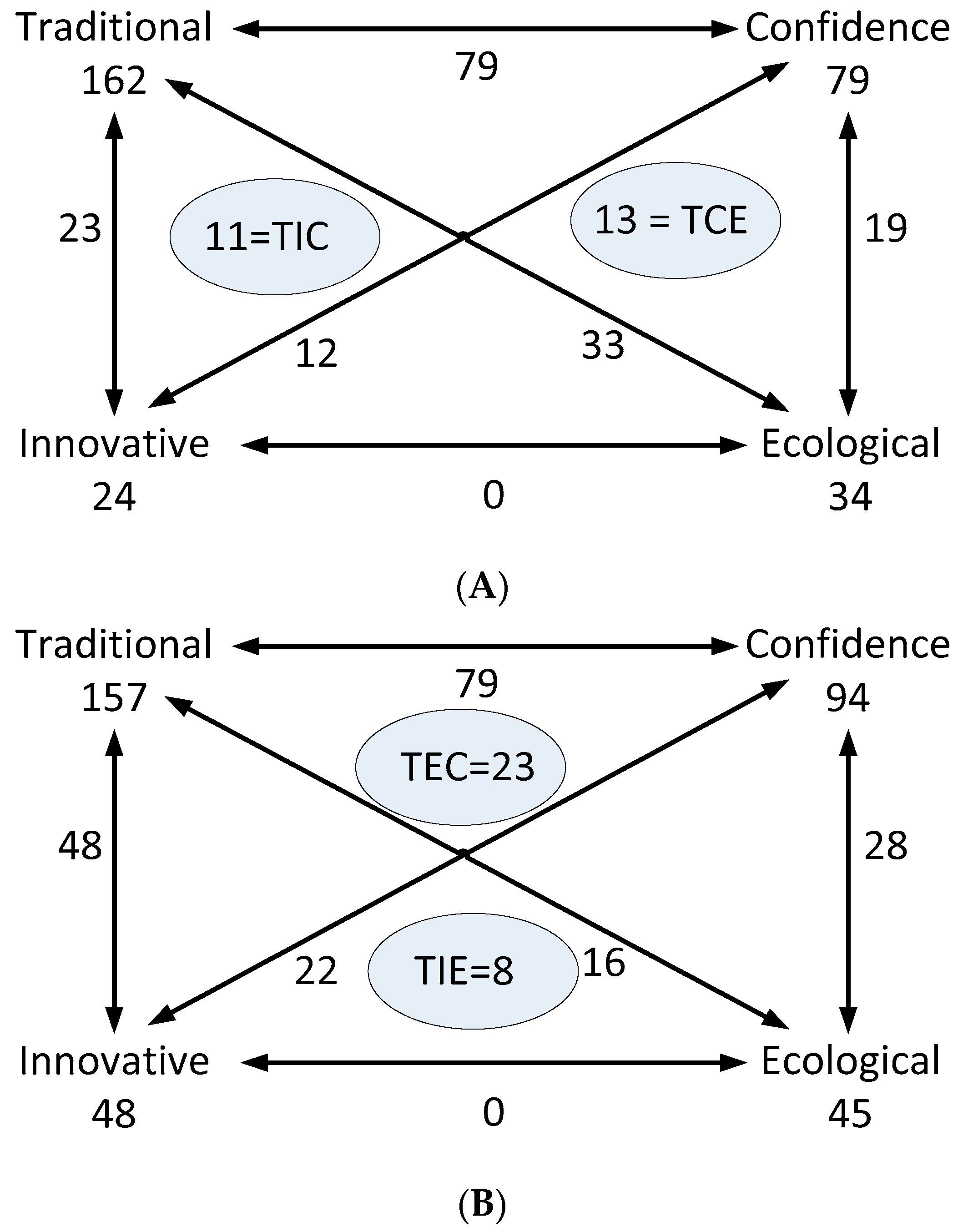

Figure 6A,B) show combinations of purchase frequencies of four types of food: traditional, confidence, organic, and innovative. For example, traditional foods have the highest number of buyers, while the shares of the others are lower. Of these, 23 students also buy innovative food (vertical arrow), 33 indicate buying ecological food (diagonal arrow), and 79 indicate their purchases as confidential. In contrast, 13 respondents buy products with three characteristics at the same time: traditional, confidential, and ecological (TCE = 13), while 11 students (TIC = 11) buy traditional, innovative, and ecological products.

Here, we can observe a slight decrease in buyers of traditional foods in the S2 period. In contrast, the number of buyers of confidential, ecological, and innovative products is increasing. The proportion of simultaneous purchases of two or three items at a time is also changing, as shown in

Figure 6B.

The results of international surveys conducted in the early period of the pandemic indicate that consumers were more radical in their spending, purchasing mainly food and household essentials, including hygiene items, while reducing purchases of elective goods [

90,

91,

92]. Changes in food consumption in Poland do not fully coincide with changes observed in other countries. Research conducted in Poland shows that, during the COVID-19 pandemic, changes in purchase volumes can be considered insignificant [

87]. However, it is worth noting that about one-fourth of Polish consumers declared that more fruit and vegetables were purchased in their households. This increase can be explained by health concerns, as fruit and vegetables are an important component of a healthy diet that can support immunity. In addition, a significant proportion of Polish consumers said they were buying more products such as flour, groats, rice, and pasta.

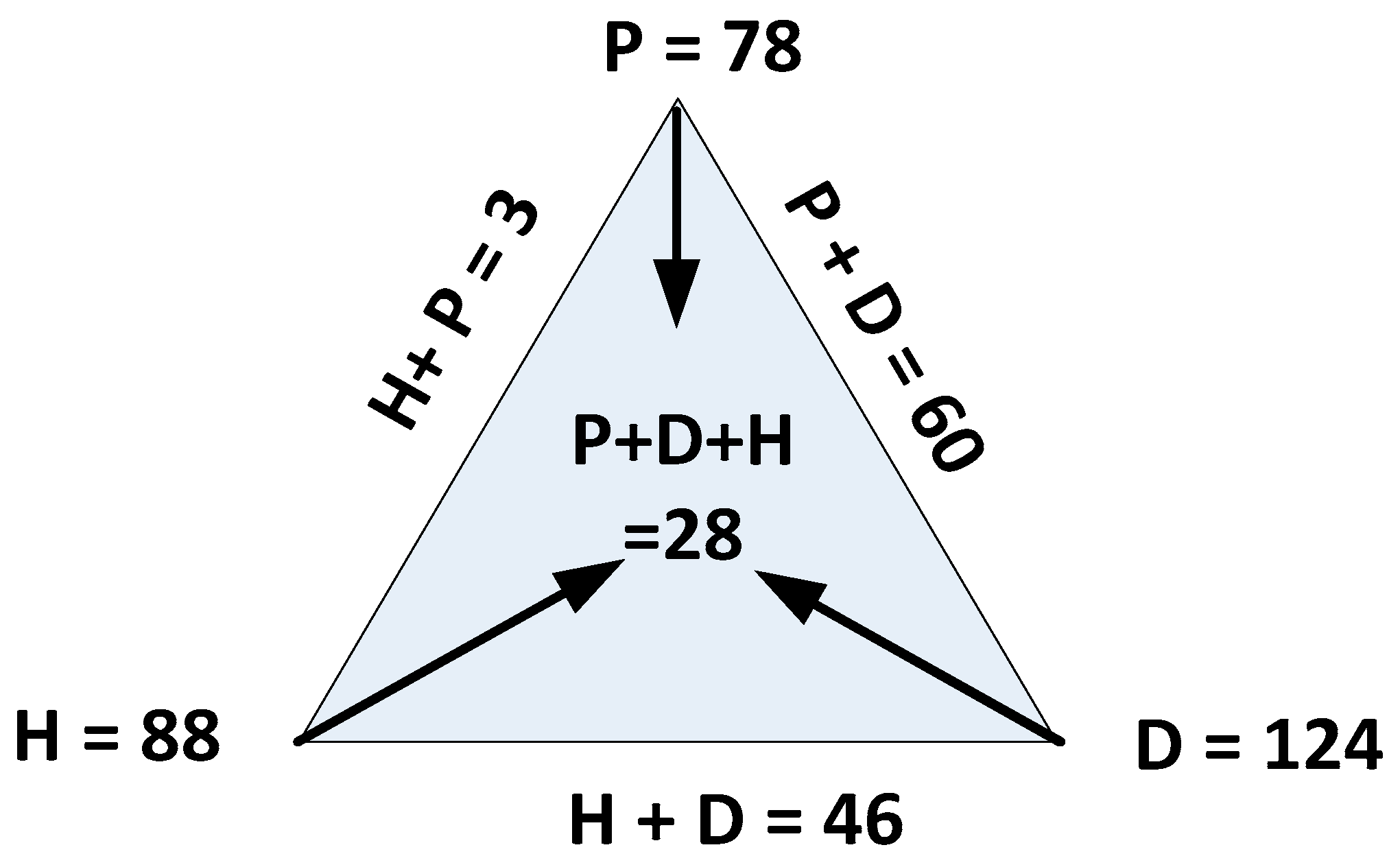

The next question was designed to investigate whether students buying processed food verify its quality characteristics: shelf life and suitability for consumption (durability—D), ingredients harmful to health (for example, the presence of allergens and energy value (harmful—H), and purpose (purpose—P). To this question, the following number of people answered the variants: P = 78, D = 124, and H = 78. Further analysis was carried out on the number of indications for combinations of two variants at the same time, for example (H + D) = 46, and even three, H + D + P = 28. This means that 46 people consider harmfulness and durability as very important, and only 3 people have this opinion about harmfulness and purpose H + P. In contrast, only 28 people attach high importance to all three parameters at the same time, as shown in the center of

Figure 7. The numbers of single characteristics are placed in the vertices of the triangle, the number of indications for two characteristics on the sides of the triangle, and the number of indications for all characteristics in the center.

Food losses due to various causes are an inherent feature of nutrition. Therefore, it is important to answer the next two questions related to identifying the magnitude of food losses of eight commodity groups during S1 and S2 among students. Information on losses of bread, flour (as well as groats and flakes), meat and processed foods, milk, vegetables and processed foods, fruit and processed foods, and beverages and juices in five ranges expressed in percentage by weight is distributed as follows: up to 2%, 5%, 10%, 20%, and above. The results are shown in

Table 1.

According to the students’ responses, small wastage (2%) of different types of food is incurred by the largest number of people during both pandemic and lockdown periods (from about 140 to 80–90). Larger wastage at an average level of 5% and above 10% occurs in dozens of people, while above 20% of food only affects no more than 11 people. Similar trends have been observed in the literature [

45]. Similarly, an empirical study conducted in 2021 among students at the Warsaw School of Economics and the University of Warmia and Mazury in Olsztyn shows that the most frequently wasted products are fruit and vegetables (about 71%), bakery/confectionery products (about 61%), and milk and dairy products (about 57%). Almost 40% of respondents declared throwing away ready-made meals and dishes, and one in four respondents most often wasted processed fruit and vegetables and meat products. Eggs (10%), fish/fish preparations, and oils and fats (about 5–6% each) ranked the lowest [

93].

It is notable that in the group with low (up to 2%) and medium levels of wastage of purchased food, there is little difference between periods S1 and S2. The number of student indications of the share of wastage in the amount of purchased products for both periods was similar, with the exception of flour and preserves in S2, where there were many more indications in the first two ranges, and for bread in the second and last range of the percentage share. However, in general, in the higher share groups for wastage of purchased food, there are lower numbers of students in S2 than in S1. The consequences of unplanned and ill-considered purchases are often wastage of purchased food. The responses in this regard to the two identical questions “Did you remember during the lockdown/pandemic risk period when shopping for food to minimize their losses by preferring the following characteristics” are presented below (

Table 2).

Depending on the type of food during the pandemic risk period (S2), the difference, albeit small, is in its favor, as more people are mindful of the drivers for reducing wastage. This relationship is shown in the following

Figure 8.

The figures presented in

Table 2 show some improvement. Each parameter shows an increase in care in preventing losses during the pandemic emergency. This is true for only a few people, but it is true for every type of food listed in

Table 2 and

Figure 8.

From the figures presented and

Figure 8, it can be seen that the sensitivity to food waste among students is higher during S2 than during S1, although there is only a difference of a few percentage points in each type of waste. As mentioned in part one of this article, the problem of the global food economy in every period from prosperity to crisis is the occurrence of massive food waste and loss, amounting to one-third of production from field to table, and much of it is generated by household members, the final part of the food chain [

47]. However, this study concludes that students have, however, scarcely analyzed these parameters with regard to wastage. This study shows that the lockdown period did not result in a revolutionary change in behavior on the farms of the surveyed students. However, in the post-lockdown period, more attention was focused on these characteristics. Similar behavior is also taking place in other countries.

International research, conducted in 15 countries and involving more than 3000 respondents, shows that for two-thirds of consumers, reducing food waste is a priority [

94]. In the case of the majority of Polish consumers, such declarations were missing, although a significant percentage of them reflect on what they buy and why [

87]. Reflecting on the problem of over-purchasing and consuming goods may indicate that future consumer decisions will be more rational. It is believed that consumers do not have an innate desire to waste food and that this phenomenon is a result of their irrational food stewardship behavior, i.e., purchase planning, shopping, food storage, and consumption [

95,

96].

The above analysis confirms the veracity of hypothesis H1 stating that “students’ food purchase decisions at the market during lockdown generated greater wastage than during the pandemic threat”. This was attributed to less frequent shopping during S1, a higher proportion of traditional products in the basket of purchased products, than during S2, also a lower propensity during shopping to verify the characteristics of food items favorable for reducing wastage, and fewer respondents planning and agreeing on purchases with other household members. The results of the study on the wastage of the eight basic food items, present for both periods (S1 and S2) of the pandemic, and despite a similar number of indications by students regarding the percentage of wastage in the purchased products, do not undermine the veracity of H1.

3.2. Purchase and Consumption of Prepared Meals vs. Food Wastage

The second part of the questionnaire inquires about the situation of purchasing prepared food to satisfy students’ consumption needs. An attempt was made to gain knowledge, firstly, about their behavior when they are not satisfied with the quality of the food provided by the university or public food services, and secondly, about the losses associated with the consumption of this food. The majority of respondents (88 people) responding to the question “do you take unconsumed food home” declare that they do not take an unconsumed meal from a cafeteria/bar or restaurant with them.

Table 3 shows the types of student responses to unsatisfactory home deliveries of ordered breakfast, lunch, or dinner. During the pandemic, spending rates on food at bars, restaurants, and other eating establishments fell. Polish consumers began to cook more at home during the pandemic. During the pandemic period, a renaissance of natural consumption (referred to as the “do-it-yourself economy”) could also be observed. The results of other studies [

97] indicate that a significant proportion of consumers began to produce goods on their own within the household (home baking of bread, cakes, preparation of preserves).

From the data presented in

Table 3, slight differences can be observed in the behavior of students for both periods. During S2, compared to S1, the total number of people throw food away only slightly less (always, often, and rarely) and this represents about 52% of the respondents. At the same time, slightly more in S2 share it with others (27%). This presentation of the respondents’ position was to some extent influenced by their existing mode of consumption regarding time, size, structure, and place. The data presented in

Figure 9 show that during lockdown (S1) about 55% of the students did not have a regulated mode of consumption in terms of time, quantity, and structure, and 37% in terms of place. In addition, only 53% of them declare that their food norms were respected during this period, although the situation was better during S2.

From the data in graphical form shown in

Figure 9, it is apparent that there were greater fluctuations during the lockdown, which leveled off somewhat afterwards. However, the observed data do not indicate fundamental changes. An assessment of food losses during ready food purchases during S1 and S2 and losses during consumption during these periods is shown in

Table 4.

About two-thirds of the respondents (between 109–119 people), when answering questions about the level of wastage, said it was stable, both in purchasing and consumption in both periods, S1 and S2. In addition, the data presented show that more than a dozen students experienced an increase in the level of wastage in both periods. However, there are more such students during S2 (29 people) than S1 regarding both food purchases at the food service market and in the process of consumption. On the other hand, a slightly higher number of survey participants than those who opted for an increase indicated a decrease during both purchasing and consumption in both periods. It is noteworthy that the number of students indicating a decrease in this phenomenon is greater for the shopping stage in period S1 than in S2 and similarly for the consumption stage.

Analysis of the data obtained in this part of the survey does not allow us to accept hypothesis H2 assuming that “At the stage of purchase of prepared food and its consumption, students behave less frugally in the lockdown period than at the stage of pandemic risk”. In both processes (purchase and consumption), students overwhelmingly, but in similar numbers, rated the losses incurred as stable for the S1 and S2 periods. At the same time, a slightly higher number of respondents indicated a decrease in losses in these processes (purchase and consumption) than an increase. On the other hand, the data of

Table 4 also draw attention to the higher number of respondents presenting pro-growth opinions of losses for S2 than for S1. However, since there was an increase in the number of people with the belief that, during S2, the degree of regulation of consumption mode increased, in terms of quantity, structure, and adherence to nutritional norms (

Figure 9), it can be assumed that in the future changes in student behavior will be directed toward increasing food savings.

3.3. Food Storage in the Student Household

The most important physical parameters that affect the shelf life of food are proper temperature, humidity, exposure, and time. Different foods have different sensitivities to the impact of these factors. Therefore, an important activity is the organoleptic inspection of the freshness of articles stored in refrigeration equipment, especially in room conditions. Almost 100% of respondents (165 people) store food in a refrigerator or freezer, and only two in a pantry. It is important to sanitize food and keep it in a condition that can preserve its desired parameters. Therefore, it becomes crucial to be entrepreneurial in reviewing food stocks (

Figure 10).

The results of the analysis of the respondents’ answers are as follows. The quality control of food inventory is most often carried out weekly and slightly less often every two days or occasionally. About 10 students perform it once a month, which should be considered reprehensible. The differences in these activities between the S1 and S2 periods are very small. Next, the respondents rated the level of food waste during storage on a qualitative scale: increased, decreased, or remained the same. The responses “increased” were few. In period S1, only 19 people indicated such a fact, and during S2 this applied to 22 students. Regarding period S1, when the participants were asked to evaluate the reasons for the increase in food waste, indicated in the first place their excessive purchases and infrequent frequency of purchases. As a result, a certain amount of food is stored longer, leading to reduced quality and even spoilage, as a cause of attrition. In contrast, hurried shopping, inattentive ordering, and sudden trips, as well as prolonged illness as causes of increased wastage had more indications from respondents in the S1 period. However, for both periods, an overwhelming number of people said that the level of wastage was almost the same, i.e., for S1, 65% of respondents, and for S2, 67%. This suggests that safe food storage is a fairly strong link in the process of food stewardship by students.

The results of the analysis referred to above do not allow us to acknowledge the truth of hypothesis H3, according to which “The level of food loss during food storage is higher in the lockdown period”. In light of the data presented, they are similar in both periods of the pandemic. Knowing how to properly store food can extend the time it is fit for consumption and thus reduce the level of food waste [

95]. At the food consumption stage, one of the most effective strategies to minimize food waste is to reuse leftover food [

95,

98]. The results of a study by D. Jakubowska [

93] confirm that managing food leftovers is a way to minimize food waste in the young consumer segment.

3.4. Assessment of Causal Factors for Reducing Food Waste in the Household at the Stages Before, during, and after Consumption

Based on the information obtained in the analysis so far, we conclude that the majority of students (91.6%) were, in both periods (S1 and S2), directly involved in the buying, storing, and culinary processing of food products and in managing food after consumption. This raises the question, in the context of assessing food losses in the household, of students’ skills related to food preparation and cooking knowledge. The metrics show that about 70% of students are members of a family household, and about 21% run the household independently. However, does this translate into efficiency in food-saving activities? In order to identify this issue, the students were asked about the level of waste created during the initial processing of food products (peeling, washing, slicing) and during cooking and baking (burning, overcooking).

Based on their responses, we can indirectly conclude that the respondents have the skills to pretreat food products (this is evidenced by the declarations of 88 survey participants, i.e., 53% of the survey sample), as according to them their products lose only 2% of their weight or mass during peeling, washing, and slicing, and 38.3% respondents indicate a level of waste of about 5%. In contrast, a level of 10 percent and greater food loss is admitted by about 10 percent of the survey participants (15 people). In the context of the students’ lack of greater experience in this area, this fact should be viewed positively. Additionally, cooking and baking activities were mastered by 79 people (47%), with only 1% admitting bad or careless actions (overcooking or burning). More food waste during this process, at 3%, was indicated by 68 respondents (41%), with only the remaining respondents (about 12%) wasting 5% or more (P30). We conclude that a low level of wastage at this stage of housekeeping has been recognized. It can even be considered to be within the range of risk of youth experimenting with new dishes and ways of using food resources.

The results of other studies indicate that each of the stages of food stewardship, i.e., shopping, planning, purchasing, food storage, and consumption, can contribute to food waste [

93]. This author’s results are similar to the data obtained in A.S. Tarczynska’s [

99] study, where the most common reasons for students to throw away food were spoilage (about 28%) and expiration (about 24%). This is also reflected in the declarations of Poles in general, who cite spoilage (65.2%), overlooking the expiration date (42%), preparing too much food (26.5%), and shopping too much (22.2%) among the most common reasons for throwing away food [

100]. Poorly planned shopping, i.e., buying unnecessary products, is, according to M. Ankiel and U. Samotyja [

18], a key factor contributing to food discarding. In addition, during the shopping process, consumers are under the impression that their needs are much greater than they actually are, leading them to buy excessive amounts of products (37.0%). Another reason for wasting food is buying groceries “just in case” and buying products in large packages (which seems to be more cost-effective) [

18]. Let us take a look at further research results on post-consumption food stewardship (

Figure 11).

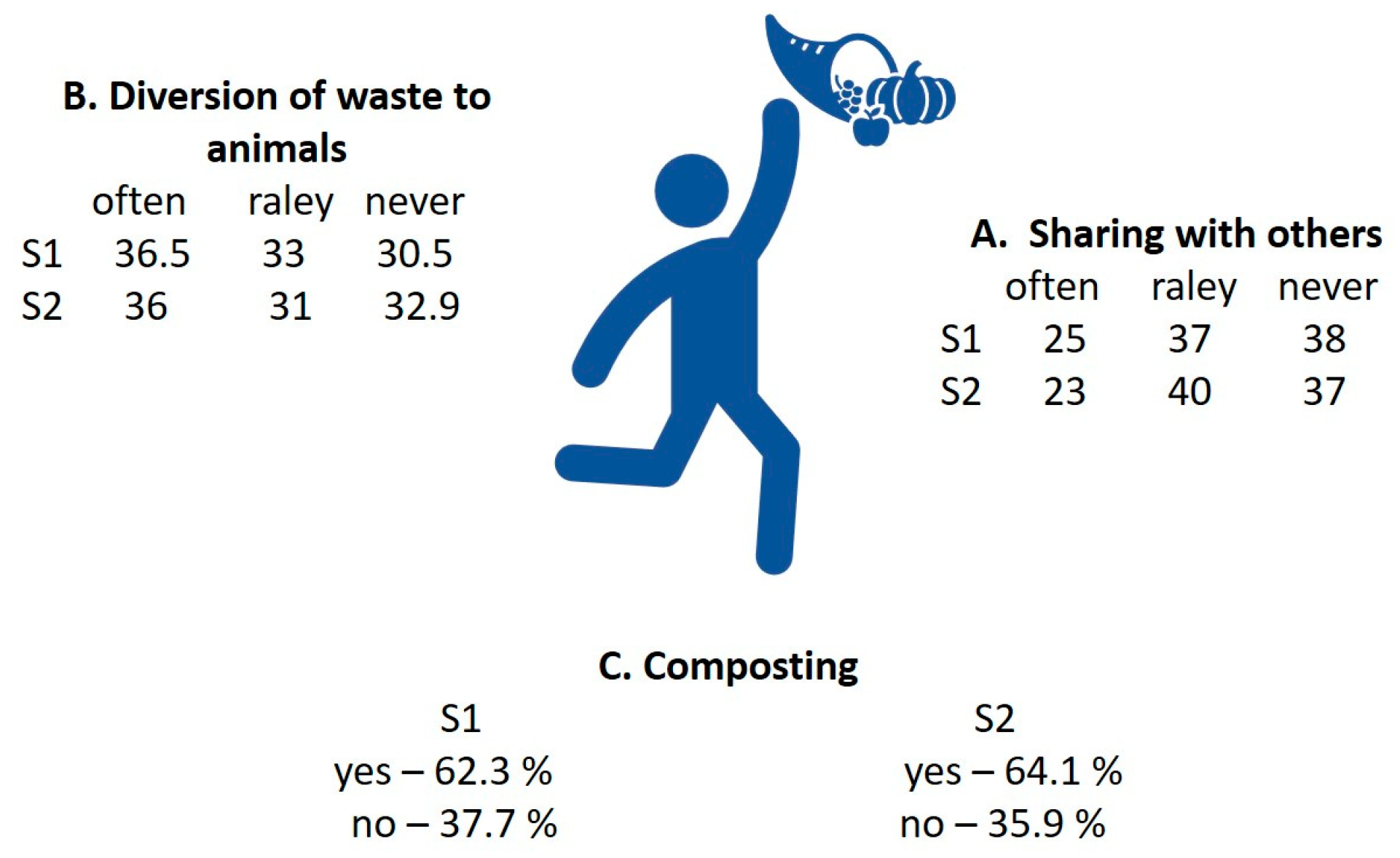

Figure 11 shows a symbolic outline of a student who, with his socially open attitude, cheerfully reflects the willingness to share food. One hand is for other people, the other for animals, and the legs are willing to recycle and compost.

From the respondents’ declarations, we can observe slight differences in the sample population, namely in the use of surplus food products in the S1 and S2 periods by transferring them to others. This refers to the propensity to share. In contrast, 63 people did not share their post-consumption surplus food in both of the analyzed periods. In terms of the prevalence of donating post-consumption leftovers to animals, the student population is divided into three almost equal numerical groups according to the indications: often, rarely, and not donating food waste to animals in both study periods. This suggests that there were similar differences in behavior among respondents in both periods, S1 and S2. This suggests the existence of specific factors shaping such a heterogeneous, but sustained in distribution, attitude among young people regardless of external conditions. On the other hand, the statement of 99 students (59.1%) about composting food waste during S1 must be evaluated positively. During S2, there was an increase in this activity, as indicated by 107 people (64.1%).

The obtained results allow us to accept hypothesis H4, which reads “The behavior of students regarding the reduction in food waste in the household showed no significant differences in the two periods studied”. Confirmation of the presented conclusions is provided by the results of other studies, which show that students are generally aware of the need to take a variety of measures, at all stages of food stewardship, to minimize unnecessary food throwing in their households. More than 86% of young consumers indicated such a need. Managing leftover food is also a common practice (72%). Most often, students use excess bread and potatoes, and make alternative dishes from other excess products, e.g., pastes or stuffings. A good solution is to control the food supplies one has before shopping, and to shop with a list of needed products [

93].

Despite the positive actions of a significant proportion of respondents to the problem of reducing household food waste, one wonders if, however, indicators of this could not be better. Were the achievements of young people in this area purposeful and conscious? Therefore, respondents were asked about the role of disciplinary measures taken in food management in this process. The results of the responses are shown in

Table 5.

The following conclusions emerge from the data presented in

Table 5:

Students were involved in pro-food-saving measures, by reducing waste, to a lesser extent in the S1 period than in S2.

In the characteristics of these undertakings, organizational issues (place of storage, purchase, mode of transportation, etc.) were mainly exposed in the S1 period, and consumer issues (food structure and quality) in S2.

On the basis of the knowledge gained so far, through the analysis of empirical data, the need to identify more deeply the factors that motivate students to save food by reducing waste arose. First, let us look at the activity of students in spreading knowledge about food saving. It is regrettable to find that, in both S1 and S2 periods, as many as 124 students (74% of the sample population) admitted to being passive. Only 23 students in each of the study periods (S1 and S2) participated in non-cash, secondary trading of food unnecessary to them. In contrast, only 6 of them used networks/social media for this purpose during lockdown and 14 after it was cancelled, while 14 and 5 respondents, respectively, informed family members and friends about the possibility of sharing food. Next, an attempt was made to identify students’ knowledge as an internal factor shaping food frugality. The formulated five questions on this subject, presented in tabular form, are contained in the last part of the survey form. They represent the nature of the respondents’ self-assessments on the issues raised in this survey. The last three questions were directed at ways of improving knowledge (

Table 6).

The response of the respondents to the first two questions can be considered satisfactory, as about 50% of the respondents responded positively. There are significantly fewer affirmative indications for the remaining questions.

Due to the very large quantitative gender disparity in the survey (67.66% of women and 32.33% of men), the distribution of responses to the first two questions in

Table 6 is presented below to highlight the differences that exist (see

Table 7). These questions are (DA) “Do you know what sustainable consumption and Consumer 4.0 mean?” and (DB) “Do you permanently improve your knowledge by using manufacturers’ information?”.

The data obtained show that women are much better informed and more decisive in matters of sustainable consumption as well as being more likely to use producers’ information on food quality.

The results of the analysis presented in

Section 3 of this article confirm hypothesis H5 in its wording “The student’s disciplinary actions in the household in terms of reducing food waste, represent a weaker side of food saving in S1 than in S2”.

The results of previous studies that took into account the micro approach to sustainable consumption, i.e., consumer behavior in individual markets, indicated that a fairly large group of consumers has an insufficient informational basis for decision-making in the sphere of consumption [

9].

The conducted research confirmed that the crisis has caused a slight evolution in consumption patterns and their modes. Therefore, it is necessary to look at the causal factors of the resultant situation in the context of the objectives of the work. The declared behavior of the respondents enables us to identify causal factors residing in the attributes of their human capital and social capital resources. From the previous considerations, it is clear that the expected changes in student behavior should go in the direction of supporting progress and abstaining from socially harmful activities.

Figure 12 contains a comparative profile of internal, nonmaterial factors, which in the theoretical model of Consumer 4.0 were adopted in the evaluation as optimal (cf. exposure of attributes

Section 2), and in the typical model of student behavior in periods S1 and S2 for this set of factors was adopted a rating validity of 5 degrees as indicated by respondents, reflected in colors.

From the above data presented in

Figure 12, a picture emerges of a gap in the internal, non-material factors of students’ behavior in both study periods (S1 and S2) in relation to the theoretical model of Consumer 4.0. Weaknesses in both cases relate to factors reflecting actions in food management, inconsistent with the principle of social rationality. This is expressed by a low rating for S1 and an average rating for S2 of food-saving activities and a low openness to purchasing health-promoting products, as well as a weak (in S1) and average (in S2) preference for meeting food needs through innovative food and higher-quality products. Corresponding with this fact is the low level of assessment in both periods of the entrepreneurial attribute defining cooperation as an important resource of social capital and the communicative attribute belonging to the reflected values. The next resource of social capital that expresses students’ thinking in the spirit of social rationality is the resource of solidarity. However, the actions disciplining their food stewardship in favor of food saving, which define this resource, were similarly rated as low for S1 and medium for S2. Moreover, the willingness to share with others, according to the respondents, was also low. In light of the considerations made, it is necessary to emphasize the unfavorable situation in terms of the rationality of consumer behavior, in the sphere of meeting food needs. Behavior based on the principles of sustainable consumption is generally rarely undertaken by a small group of young consumers. On the other hand, the stronger factors of the respondents’ behavior in both periods include human capital resources, which reflect the attributes of the students’ skills in food preparation, as well as knowledge and willingness to learn and awareness of choice.

In general, however, the identified gap occurring between the causal factors in the typical model of student behavior in S1, in relation to the Consumer 4.0 model, is larger than in S2. This is because, in the first case, the number of factors of the respondents’ low-level behavior is significantly higher. However, there is not even one factor in both periods whose evaluation in the type of model is comparable to the required level in light of the theoretical model of Consumer 4.0. The above findings positively verify hypothesis 6 as follows: “There is a gap between the typical model of students’ behavior and the Consumer 4.0 model reflected in their internal factors in food stewardship”.

Let us remember that it takes a long time to study consumer attitudes and behavior, but then the results of the analysis are burdened by the disturbance of external conditions. In this case, this variability of household conditions also occurred suddenly, as an independent, external factor, introduced by top-down directives. The question arises as to what lessons young consumers have learned for better food stewardship, in reflection of this sudden change during the lockdown, are probable to be repeated in the future. The answer is provided by comparing the consumer behavior of students in periods S1 and S2 in

Figure 11. The analysis of the factors indicates an increase in the preference to purchase, in the time after the lockdown was cancelled, innovative and higher-quality products. There was an increase in disciplinary actions among respondents to reduce food waste and commitment to saving food. Other factors remained unchanged.

4. Conclusions

The authors, recognizing the gap in the existing secondary sources on the study topic, first identified important economic categories between which there are relations relevant in the cognitive process for solving the defined research problem. They also generated a theoretical model of Consumer 4.0 oriented toward socially rational behavior in food stewardship. Subsequently, important research hypotheses were formulated corresponding to the different stages of this stewardship, as well as diagnostic questions for respondents concerning the evaluation of facts, motives of behavior, and opinions. The measurement tool was a survey questionnaire used to conduct an empirical study among students to obtain primary data. They constituted a representative research sample of the faculty community.

Capturing tacit knowledge from respondents as individual, often unconscious, knowledge, is a major challenge for researchers. The objects of exploration of this knowledge are, in the presented work, intangible factors such as culture, dimensions, and attributes of social capital and human capital. Their changes toward socially rational food management by students were studied directly in two spheres (in the market and in the household) and indirectly in the third sphere—in the environment. Research regarding soft factors is difficult. In this case, it was necessary to identify the key values reflected by Consumer 4.0. One of them is avoiding food waste. Others include, for example, choosing pro-health or innovative products that save energy consumption in their creation and products of local origin.

This study performed a critical analysis of the results achieved for the verification of theoretical findings, the results and discussion of which, as well as suggestions for directions for further ex ante research, are presented below.

The thrust of the presented article is primarily to provide new knowledge on the causal factors shaping the growing role of college students in increasing food savings by reducing food waste. This is related to the need to identify the gap of factors motivating students to such behavior, in accordance with the paradigm of sustainable consumption, in the trend of the emerging Consumer 4.0. At the outset of the study, it was assumed that the period of the COVID-19 lockdown caused more food waste than the period of the pandemic threat after the cancellation of the lockdown. The reasons for this were attributed not only to factors hindering the production of food raw materials, broken food chains, or outages of food processing companies, but also to excessive purchases of food for so-called “stockpiling” by households. The question arose of how did students actually behave as consumers during these two periods in meeting their food needs?

The choice of two periods for the study was deliberate for comparative intent. The first S1, the lockdown, was characterized by a restriction of freedom in purchasing decisions, while the second S2 was characterized by full consumer decision-making. What behaviors did the students exhibit in these situations, in the face of the idea of striving for increased food safety and sustainable consumption? In the third decade of the 21st century, the construction of Industry 4.0 in Poland is becoming more advanced. This phenomenon is being followed by the formation of Consumer 4.0. This also applies to Food Processing Industry 4.0, as all participants, regardless of age, location, and gender, are included in the process of creating its product. These changes in the consumer’s inclusion in the food-saving process may have been accelerated by the pandemic, shaping a Consumer 4.0 oriented toward the social rationality of food stewardship in their decisions. Does the behavior of students regarding food stewardship confirm that the lockdown accelerated its formation? The conducted research did not provide a clear answer for the entire food management process. The results indicate that the differences in the respondents’ behavior were influenced by the stage (link) of the process.

Of the five working hypotheses, only two of them support the formulated main hypothesis, which reads: “Students’ behavior in the process of food stewardship during lockdown was less conducive to food savings than during the pandemic threat.” It was found that, only for the market purchase of food products (H1) and the student’s disciplinary actions in the household to reduce waste (H5), the S1 (lockdown) period performed worse. In contrast, hypotheses H3 and H4 indicated the same behavior of students in both periods; that is, food storage and food utilization behavior in the household. On the other hand, in the separate link of ready-to-eat food management, i.e., purchase at the food service market and its consumption (H2), adolescents behaved less sparingly in S2 than in lockdown (S1). In view of the above, the main hypothesis cannot be accepted as true. We conclude that it was only partially positively verified, which leads the authors to reject it.

Accelerating changes in student consumer behavior toward the emerging Consumer 4.0 requires an increase in the strength of internal factors through greater involvement in their growth by the environment, namely organizations and policies that create formal institutions to support the process. The existing global imbalance hinders effective action in national economies in this regard on the micro and macro levels. It is worth noting that Poland is self-sufficient in basic food products. Therefore, no attention has been paid to developing mechanisms to effectively prevent waste. This research allows us to conclude that even lockdown has not forced greater pro-food-saving reflection among students. This is because consumer behavior is grounded in culture and historical experiences, which are the basis of attributes of social and human capital. Poland seeks to increase participation in preserving the non-renewable resources of the environment, creating sustainability and food security globally. This requires the formation of those informal institutions which are the basis for the growth of factors that foster social rationality in food management, including the propensity to save food.

The conclusions from the presented research do not fully exhaust the topic addressed, but they are an important observation in the discussion of the development of research and analysis of consumer attitudes and behavior toward the idea of sustainable consumption, as well as educational campaigns aimed at young consumers [

101,

102]. The obtained results contribute to emphasizing the importance and relevance of research on the phenomenon of food waste, which has now become a global problem. Food waste generated in households is currently the main source of food waste in developed countries. Understanding consumer behavior related to food waste and identifying key factors affecting the control of household food waste levels are very important for the development of sustainable food systems.

Shaping consumer behavior requires an interdisciplinary approach. Future research directions on the subject should place the consumer in the role defined by the FAO and the EU toward greater involvement in reducing food waste. It therefore becomes important to implement instruments of external stimulation, accelerating changes in consumer behavior in the expected direction.

One of the most significant changes differentiating the attitudes and behaviors of consumers of different generations is the culture of consumption. It becomes urgent to study its impact on consumer behavior in food management on a regional basis.

Food is a component of the F–E–W (food–energy–water) nexus, and its loss is associated with the waste of the other two components. It is necessary, on the one hand, to reduce food loss, and on the other hand, to seek new technologies that reduce water and energy consumption. This can be achieved by developing more energy-efficient methods of processing and technologies for its purification. The signaled measures, however, will require a wider use and understanding by consumers and producers of the principles of the circular economy, as well as increased investment in research and development. Increased education of society members in the early stages of their development (young people, students) will enable them to be involved in the formation of a resource-saving economy.

In summary, the conclusions from the research are presented below in a synthetic way:

During the lockdown, there was less willingness to save food by reducing waste than during the pandemic threat. However, this applies only to the phase of purchasing food products at the market and disciplinary actions in the household.

Therefore, the main hypothesis was not confirmed. In fact, in both periods (S1 and S2), in the remaining stages of food management, the consumer activities of students are similar, but are still not particularly focused on reducing food waste.

This means that the pandemic crisis has caused little reflection and evolution in consumption patterns. The reason for this phenomenon is the existing gap of intangible, internal factors used by students in economic activity.

The identified factor gap is the difference between the value of resources and attributes of human, social, and culture capital, reflected in a typical model of student behavior, resulting from empirical research, in relation to the Consumer 4.0 model.

The Consumer 4.0 model presents the key values of those intangible factors of society that are necessary for the implementation of activities in the sustainable development paradigm.

In view of the above, overcoming the factor gap and accelerating the change in consumer behavior toward sustainable development requires external support from institutions and organizations. This intervention should ensure the improvement of the resources, quality, and structure of intangible factors that are necessary in the food management process by consumers and other actors in the food chain.