Abstract

With the Clean Energy for all Europeans legislative package, the European Union (EU) aimed to put consumers “at the heart” of EU energy policy. The recast of the Renewable Energy Directive (RED II) acknowledged the importance of energy communities for the energy transition and introduced new provisions for renewable energy communities (RECs), empowering them to participate in the energy market. This article analyses the progress of transposing and implementing key provisions of the RED II that apply to RECs in nine European countries and focuses on timeliness and completeness of transposition. It comprises both a qualitative and quantitative assessment covering (1) the definition, rights, and market activities of RECs; (2) key elements of enabling frameworks; and (3) consideration of REC specificities in support schemes for renewable energy. The analysis shows considerable variation in transposition performance between the analysed countries. The authors investigate the reasons for this variation and relate them to findings of European implementation and compliance research. Key factors identified include actor-related and capacity-related factors, institutional fit, and characteristics of the RED II itself. Future research in this field needs multi-faceted avenues and should pay particular attention to the influence of national governments and incumbents, not only in the transposition process, but already in upstream policy formulation at the European level.

1. Introduction

1.1. European Legislation for Renewable Energy Communities

With its Clean Energy Package (CEP), the European Union (EU) has formally recognised energy communities as key actors in the transition of the energy system towards a more decentralised use of renewable sources, thus signalling a shift in the role of citizens from passive consumers to active participants [1] (p. 233). For the first time, EU legislation acknowledged the role of community ownership in supporting the realisation of European climate and energy goals. In particular, the recast Renewable Energy Directive (EU) 2018/2001 (RED II), the Internal Electricity Market Directive (EU) 2019/944 (IEMD), and the Internal Electricity Market Regulation (EU) 2019/943 (IEMR) contain provisions that establish a supportive EU legal framework for so-called renewable energy communities (RECs) and citizen energy communities (CECs). Both concepts are related and have partly overlapping, partly different elements (for a comparison see [1,2]).

The focus of this research is on RECs. These are defined in the RED II as legal entities whose shareholders or members are natural persons, small and medium-sized enterprises, or local authorities, including municipalities (RED II, Article 2(16) (b) and (c)). RECs need to be based on open and voluntary participation. They should be “capable of remaining autonomous from individual members and other traditional market actors that participate in the community as members or shareholders, or who cooperate through other means.” (RED II, Recital 71). Moreover, RECs should be effectively controlled by shareholders or members located in the proximity of the renewable energy project(s) owned and developed by the respective entity. The primary purpose of RECs should be to provide environmental, economic, or social community benefits for their shareholders or members, or for the local areas where they operate, rather than financial profits (RED II, Article 2(16)).

The RED II explicitly recognises that the activities of RECs are not limited to the collective production of renewable energy and broadens the scope to include consumption, storage, and sale of the renewable energy produced. Moreover, RECs should be entitled to share within their community energy generated by the production units owned by the REC and to have access to all suitable energy markets in a non-discriminatory manner (RED II, Article 22(2)). Implicitly, RECs may also engage in activities such as the distribution and supply of energy (RED II, Article 22(4e)). Member States are expected to transpose the definition, rights, and duties of RECs, to assess existing barriers and potential of development, and to create an enabling framework to promote and facilitate the development of RECs. Article 22(4) of the RED II includes a comprehensive list of the elements an enabling framework shall comprise. These include, inter alia, removal of unjustified or discriminatory conditions; provisions ensuring the cooperation of distribution system operators (DSOs) with RECs to facilitate energy sharing;, fair, proportionate, and transparent procedures; accessibility of all consumers—including low-income and vulnerable households—as well as tools to facilitate finance and information. Furthermore, Member States are called to take into account specificities of RECs when designing support schemes for renewable energy in order to allow them to compete for support on an equal footing with other market participants.

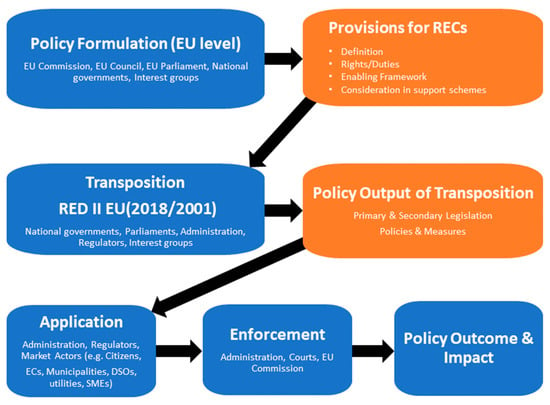

The deadline for transposing the RED II expired on 30 June 2021. The implementation of EU directives does not only require their timely, complete, and correct transposition into the different legal systems of all Member States but also their application and enforcement by national authorities [3]. Enforcement may involve judicial action and necessary sanctions in the case of non-compliance. Figure 1 illustrates the three different stages of implementation.

Figure 1.

Stages of implementing EU directives (Source: Authors’ elaboration based on [3]).

1.2. Purpose and Structure of the Paper

The purpose of this paper is to provide an evidence-based, empirical analysis of the progress of transposing the key provisions of the RED II that apply to RECs. The primary aim is not to investigate what the provisions examined bring about for REC development in practice (outcome), but rather whether they have been transposed timely and completely in terms of their objectives (output) [4] (p. 139).

The study area includes nine European countries with different stages of community energy development: Flanders (Belgium), Germany, Italy, Latvia, The Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, and Spain. Our assessment covers definitions, rights, and market activities of RECs and the extent to which governments managed to create an enabling framework to promote and facilitate the development of RECs. The paper is structured as follows. The next subsection provides a review of the relevant literature and illustrates the added value of this study. Section 2 describes the research design and methodological approach of the performed assessment, including the analytical framework, data sources, methods, and criteria for country selection. Section 3 presents the research results, while the discussion part in Section 4 takes a comparative perspective, focusing on timeliness and completeness of transposition. It also identifies similarities and differences between the countries. Furthermore, this section attempts to explain transposition variance between countries and draws some tentative conclusions. On the theoretical side, it builds a bridge between community energy research and European implementation and compliance research, the latter being closely related to the broader field of Europeanisation research [3,5]. The concluding section provides lessons learned and indicates needs and possible avenues for future research.

1.3. Literature Review and Novelty of the Research

There is a growing academic interest in the EU’s Clean Energy Package and the corresponding directives, their characteristics, evolution, implications, and implementation [1,6]. This paper can be placed within the body of research analysing the implementation of the Clean Energy Package and its provisions for RECs and CECs by European Member States.

This includes the following:

- Analyses of single countries (e.g., Austria [7,8,9]; Germany [10]; Spain [11]; Sweden [12]; Italy [13,14,15,16,17,18,19]; The Netherlands [20]);

- Comparisons of two countries [21,22,23,24,25];

- Cross-country comparisons of a larger number of countries [7,26,27,28,29,30,31,32].

Several scholars and practitioners have addressed the challenges related to the transposition and provided reflections, guidance, and best practices to facilitate the transposition process [1,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41].

Most comparative, multi-country studies have concentrated on specific elements of the transposition process including legal definitions and rights of RECs [2,15,26,31]; their integration into the electricity grid structure [7]; the inclusion of women, low-income, and vulnerable households [42,43]; and policy support [41] or other elements of an enabling framework for RECs [44].

However, only a few cross-country studies investigated the transposition in a comparative, comprehensive, and systematic manner also covering the minimum requirements an enabling framework must comprise according to the RED II. Hannoset et al. [45] provided one of the first comprehensive and systematic overviews of the existing and emerging legal and regulatory framework for energy communities in nine EU countries covering the existing energy community landscape, definitions of RECs and CECs, governance principles, rights, market activities and responsibilities, selected elements of an enabling framework, financial incentives, and support measures. Toporek and Campos [29] assessed the regulatory frameworks and policy instruments for renewable energy-based prosumer initiatives in the EU and in nine participating Member States. Their analysis also covered RECs focusing on definitions, rights, incentives, and barriers. In 2020, the same authors re-assessed the transposition progress related to RECs and CECs in six countries by referring to the integrated National Energy and Climate Plans [30].

Campos et al. [46] carried out a comprehensive and systematic cross-country comparison of the regulatory frameworks in nine countries to reveal key challenges and opportunities that these have posed to different types of collective prosumers including RECs. Frieden et al. [27] assessed the transposition of specific elements of the Clean Energy Package in six EU Member States complemented by insights from a previous analysis of all 27 EU countries. The researchers scrutinised the general definitions and differentiation between RECs, CECs and collective self-consumption, governance and ownership issues, activities, grid tariffs, support mechanisms, and other issues. The paper shows that the national approaches and the pace of transposition differ greatly. The authors conclude that while basic provisions are in place in most Member States to meet the fundamental EU requirements, the overall integration into the energy system and market is only partly addressed.

Although several comparative studies detected variation between Member States in terms of transposition performance, the reasons for these differences have not been explored systematically yet. Coenen and Hoppe [6] advocated for more research into the factors that explain the differences between EU countries in transposing the Clean Energy Package into national legislation and policy support mechanisms, including front-runners and late-starting countries. This paper contributes to close this research gap. It assesses systematically the transposition progress including the elements of an enabling framework and support scheme design and provides updated analyses from nine countries. In contrast to many other relevant transposition studies, this article offers a comprehensive analysis of the enabling frameworks and support scheme designs. Its main novelty is the fact that it links research on community energy with European implementation and compliance research, looking for fruitful approaches to explain transposition delays, gaps, and variation between Member States. Moreover, the article covers several countries which have received little scientific attention in the community energy literature so far, in particular Latvia, Norway, Poland, and Portugal. To the authors’ knowledge, this specific group of countries have not been analysed comparatively all together in any previous study.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design, Data, and Methods

The article aims to analyse how different countries have transposed the RED II provisions for RECs into national legislation. The analysis is guided by the following research questions:

- (1)

- To what extent did the countries/regions under scrutiny transpose the REC definitions and rights as well as the elements of an enabling framework for RECs, as specified in Art. 22(4) of RED II?

- (2)

- To what extent did they consider the specificities of RECs in their support schemes for renewable energy sources (RES), pursuant to Art. 22(7) of RED II?

- (3)

- To what extent have the respective provisions been transposed timely and completely? Where can transposition delays and gaps be identified?

- (4)

- How can transposition delays, gaps, and variations in transposition performance be explained?

This investigation has been carried out on the basis of a critical interpretative epistemology [47]. The research design follows a qualitative empirical approach comparing the transposition process in nine countries. Qualitative research has been characterised as “interpretive, hermeneutic, inductive, heterogeneous in methods or using multiple methods, reflexive, deep, rigorous, and rejecting the natural sciences as a model” [48]. In this tradition, this article makes use of a process of induction rather than using the data to prove an established theory. We test propositions rather than base our deductions on hypotheses that are derived first from theories and then tested empirically against observations (as it would be in deductive reasoning).

To answer the research questions and pursue the aforementioned objectives, the assessment has been subdivided into three sections examining the following issues: (1) definition, rights, and market activities of RECs, (2) key elements of enabling frameworks, and (3) political objectives and consideration of REC specificities in support scheme designs. Table 1 provides an overview of the different elements of the analytical framework.

Table 1.

Elements of the analytical framework.

The data analysed are drawn from an assessment carried out in the frame of the Horizon2020 project COME RES [49]. This project took a multi- and transdisciplinary approach to facilitate the development of RECs in Belgium (Flanders), Germany, Italy, Latvia, The Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, and Spain [23].

The key methods applied to answer the three descriptive research questions include descriptive (legal) studies, document, and literature analysis. Data collection relied on (draft) laws and regulations, policy papers, official government reports, official information provided by EU organisations (e.g., EUR-Lex databases, public information on infringement procedures), previous academic analyses, reports of European collaborative projects, reports and opinions of associations and non-governmental organisations (NGOs), media coverage, and websites. Further evidence to support the analysis has been derived from dedicated stakeholder consultations carried out in the frame of the COME RES project and the findings of the so-called ‘country desks’, informal stakeholder forums established during the project in the nine countries. Further, electronic databases and search engines (primarily Web of Science, Google Search, Scopus, and ScienceDirect) were utilised to conduct the document search. Additional literature was identified via snowballing techniques, such as reference chasing and tracking citations.

The investigation of the country-specific state of transposition was carried out by national research teams within the COME RES consortium. These included scientists and experts in the fields, supported by legal experts. A questionnaire with mostly open-ended questions was elaborated in cooperation with the research teams. This questionnaire was organised into four main sections reflecting the elements of the analytical framework (see Table 1). Most of the data sources listed above were also used to investigate the fourth, causal research question.

Many empirical studies assessing the timeliness of transposition rely on data on notified national laws or infringement proceedings. In both cases, the level of analysis is usually that of one or several entire directives. However, once the research focus shifts to the completeness and correctness of transposition, the mere analysis of compliance on a directive level may be inappropriate since directives consist of numerous articles and sub-articles (i.e., provisions) prescribing specific requirements countries should comply with through national legislation. Implementation research has shown that there is variation in Member States’ compliance with different provisions of EU directives [50]. The paper contributes to this type of research by examining specific provisions within a directive.

Following [51] (p. 218), the authors interpret compliance not as a dichotomous concept (existing/non-existing), but as a concept whose expression can be specified on a continuum. In addition to the qualitative assessment, the research teams carried out a quantitative assessment of the transposition completeness in each country. The quantitative assessment is based on a 0–5 points rating system, which was calibrated for each analysed element individually. Table 2 provides a schematic and generalised translation of the calibration table, illustrating the general approach that was applied to assess transposition performance.

Table 2.

Schematic rating system for the quantitative assessment of transposition performance.

The ratings reflect the transposition status as of 15 July 2022. The quantitative assessments were graphically translated with the help of dot charts illustrating the transposition performance (see Section 4).

2.2. Country Selection

This article focuses on eight EU countries and Norway. The sample of countries includes the following:

- (1)

- Pioneering countries where community energy is in a comparatively advanced stage of development and/or which had already regulations and support measures in place when the Clean Energy Package was adopted at the European level (Germany, The Netherlands, Flanders in Belgium).

- (2)

- Follower countries that have at least partly/regionally supported traditions of community energy, and where recently the development of energy communities is growing constantly (Italy, Spain).

- (3)

- Countries where community energy has been underdeveloped so far and where energy communities are in an embryonic or early stage of development (Latvia, Poland, Portugal, Norway).

The cases reflect the heterogeneity in Europe and allow for a comparison across North, East, West, and South Europe. Due to the federal structure in Belgium, the transposition of the RED II, including the provisions for RECs, is a competence of the three regions (Flemish Region, Walloon Region, and Brussels Capital Region). This assessment focuses on the region of Flanders. Norway is not an EU member, but part of the European Economic Area (EEA). The implementation of the RED II will be dependent on the negotiations between the EU and the EEA. Nevertheless, Norway represents an appealing case because it illustrates the relevance of EU rules even if these are not mandatory in a particular non-EU country. Figure 2 illustrates the geographical position of the analysed countries.

Figure 2.

Geographical position of the analysed countries marked green (Source: Authors’ elaboration).

2.3. Methodological Strengths and Limitations

Research on transposition timeliness, completeness, and correctness of EU directives is partly based on qualitative, and partly on quantitative methods, including large-N studies (for an overview see [52]). Many quantitative studies have drawn on Member States’ official notifications of the respective transposition(s) and/or, official data on infringement procedures initiated by the EU against Member States. However, for several reasons these data sources face certain limitations in terms of validity, particularly concerning completeness and correctness of transposition [3] (pp. 18–19).

The authors of this article have therefore chosen a qualitative approach to appropriately catch the temporal and substantive dimension of transposition. However, the analysis of transposition completeness is partly based on individual expert assessments and therefore is inevitably subjective. Transposition of the RED II is still in progress and secondary legislation is being developed in most analysed countries. Therefore, it is too early to fully assess completeness and substantive correctness.

3. Results

The following section presents the key results for each of the countries/regions examined. The description of the results follows the structure of the analytical framework as delineated above.

3.1. Flanders

Flanders, one of the three Regions in Belgium, has a historical tradition of cooperatives and, to a limited extent, anti-nuclear mobilisation, which has been identified as one of the key enablers for the development of energy communities [44] (p. 12). Community energy in Flanders is relatively well developed with 21 cooperatives being members of REScoop Vlaanderen, the regional association of renewable energy cooperatives. In the Flemish Region, the definitions of RECs and CECs were incorporated in June 2021 by amendments to the Flemish Energy Decree of 8 May 2009 and the Energy Decision of 19 November 2010. The transposition of REC definition, rights, obligations, and possible activities can be regarded as quite advanced. The Energy Decree frames ‘energy communities’ as a single concept, with CECs and RECs representing slightly different notions of this concept. The type of legal entity that a REC will take has not been defined yet, but most likely only cooperatives and non-profit organisations comply because of the criteria stipulated in the RED II. Several principles such as autonomy or proximity are not elaborated on in detail and require further specifications. Compared to many other countries examined, Flanders has made progress in establishing provisions for energy sharing. It has chosen a phased roll-out, starting with collective self-consumption on the building/multi-apartment block level, followed by peer-to-peer trading and energy sharing between members of a REC. Three pilot projects are currently being implemented.

However, the enabling framework for RECs is generally weak and fragmentary. Access to information and financing as well as the lack of cost-reflective network charges based on a transparent cost–benefit analysis represent particularly important transposition gaps. Furthermore, there is a need to establish one-stop-shops providing information, administrative, and financial support to local RECs. Access for vulnerable and low-income households should be facilitated. Furthermore, the enabling framework should support capacity building of local authorities so local policy makers can take up a more active role in the promotion and further development of RECs. In the meantime, the Flemish government, the regulatory authority and the distribution grid operator are undertaking steps to implement the regulatory framework and further develop the enabling framework for energy sharing and RECs in Flanders by, e.g., launching a cost–benefit analysis on grid tariffs, facilitating the access to information and tools on energy sharing (through the existing Federation of Renewable Energy Cooperatives, REScoop.Vlaanderen), operationalising an information technology system that enables energy sharing, and setting up a call for tenders specifically for energy communities and energy sharing in apartment buildings. DSOs are required to carry out the transactions required for energy sharing and selling. DSOs have to register the different forms of energy exchange, check participation conditions, and report shared energy volumes. Support schemes and economic incentives specifically targeting RECs are underdeveloped. Regulations and financial support mechanisms need to be adapted to consider the specific characteristics of RECs, as they often develop small-scale projects and aim to share the energy produced amongst their members (and to not maximise self-consumption).

3.2. Germany

Germany has a long tradition of collective initiatives in the energy sector, dating back to the early 20th century when electricity distribution cooperatives played a key role in the electrification of rural areas, although only a few of them persist [53]. In 2016, approximately 1700 community energy initiatives existed, while slightly more than 50% were organised as energy cooperatives [54] (p. 38). Energy cooperatives experienced a particularly dynamic development between 2008 and 2013 [55]. When the RED II took effect, Germany already had a definition and certain support measures for ‘citizen energy companies’ in place. Nonetheless, the previous federal government, a coalition of Christian Democrats and Social Democrats, failed to timely and completely transpose the RED II and its provisions for RECs. Because this government has been particularly reluctant to facilitate collective self-consumption on a building/multi-apartment block level and energy sharing especially, in August 2021, the Citizens’ Energy Alliance (Bündnis Bürgerenergie) together with other NGOs and associations filed a complaint with the European Commission demanding to initiate infringement proceedings against Germany [56].

By contrast, considerable progress has been made under the current federal government of Social Democrats, the Green Party, and the Liberal Party. The pre-existing legal definition of ‘citizen energy company’ was amended in July 2022 to fully comply with the provisions of the RED II for RECs and also to avoid misuse by other market actors (which happened in the past, see [57]). The updated definition considers and specifies the principles of effective control, proximity, and autonomy. At least 75% of the voting rights of a REC must be held by natural persons living in a postcode area that lies completely or partly within a radius of 50 km around the plant. A member or shareholder of a ‘citizen energy company’ is not allowed to hold more than 10% of the voting rights.

The legal definition still has a rather narrow scope of application, which is limited to electricity generation based on wind energy and solar photovoltaic (PV) energy. ‘Open’ and ‘voluntary’ participation have not been explicitly transposed into national legislation. In the annotations to the amended Renewable Energy Sources Act, the ‘primary purpose’ has been mentioned by referring to the formulation of the RED II, but without any further specifications. Rights, duties, and possible market activities of RECs have not been explicitly laid down, although in practice energy communities are engaged in various activities including electricity storage, consumption, aggregation, sales, or in a few cases, even operation of distribution grids. Collective self-consumption on a building/apartment block level and energy sharing represent particularly significant transposition gaps. The present government aims at first to overhaul the electricity market design, including a reform of the grid charges, and then introduce energy sharing. Moreover, there are concerns among policy makers that reduced (grid) charges for RECs can potentially lead to higher system costs for those consumers not participating in energy communities. Policy makers also question the benefits and value added of energy sharing [58]. Financial support for RECs is available in diverse forms, such as low-interest loans [10,32] (p. 14). Furthermore, access of RECs to risk capital and start-up financing has been improved. Inspired by the example of the federal state Schleswig-Holstein, the federal government has recently set up a dedicated support programme for wind energy projects of citizen energy companies.

Although the present government has also taken several measures to streamline the complex and lengthy project planning and permitting procedures in cooperation with the state (Länder) governments, essential elements of the enabling framework for RECs are still missing. These include provisions that facilitate cooperation between RECs and DSOs to enable energy sharing. Moreover, there is a need for information, advice, and capacity building. The federal government should introduce a regulatory framework for collective self-consumption and energy sharing, facilitate their practical implementation, continue to reduce the administrative barriers in spatial planning and permitting, as well as to extend the support programme for citizen energy companies to also include other RES technologies.

In July 2022, the federal government decided to exempt wind and solar projects of citizen energy companies that fulfil the ‘de minimis’ rules laid down in the European Guidelines on State Aid for Climate, Environmental Protection and Energy 2022 (2022/C 80/01) from the obligation to participate in auctions for financial support. Since 1 January 2023, these entities are eligible for a market premium which is linked to the auction results of the previous year (for PV) or of the year before the last (for wind).

3.3. Italy

In May 2022, the number of operational energy communities in Italy reached 35, which is still modest compared to northern and western European countries. Italy, however, does not represent a new terrain for collective forms of energy production. There is a certain tradition of hydroelectric cooperatives that emerged during the first half of the twentieth century in the Alpine area of the country [13,44]. Italy gained further experience with energy communities during the 2000s, particularly in the period 2008–2013. Today, the community energy segment in Italy can be characterised by small initiatives fairly dependent on policy support for PV [14].

In Italy, the RED II has played a catalyst role for the development of energy community initiatives [23]. The government took early steps to transpose the respective RED II provisions anticipating European rules for RECs, and the recent years have witnessed an impressive evolution in the development of national and regional policy frameworks. The diffusion of energy communities has recently gained new momentum and in addition to the 35 communities in operation, in 2022 the environmental NGO Legambiente identified 41 energy communities that were planned and 24 that were taking the first steps towards foundation [59].

The transposition of RED II provisions for RECs can be described as an iterative process encompassing the enactment of several consecutive legal acts. With Legislative Decree 162/19, Article 42-bis (Decreto Milleproroghe 2019), the Italian legislator opened the possibility of using collective self-consumption of renewable energy produced by installations with a capacity of less than 200 kW on an experimental basis. After a transitional phase of 18 months, the transposition of the provisions for RECs was largely achieved with the Legislative Decree No. 199 of 8 November 2021, which amended the earlier definition. Criteria such as open and voluntary participation, autonomy, effective control, and proximity have been explicitly transposed and mostly further specified. Some of the initial restrictions in terms of capacity or proximity have been softened, but RECs still face certain limitations. Although RECs are explicitly entitled to produce, consume, store, share, and sell renewable energy, other activities including the operation of distribution networks or supply of energy are not possible. Italian legislation stipulates that REC members must be connected to the same primary cabin (medium voltage substation) and that the electric capacity of a generation plant controlled by a REC must not exceed 1 MW. Each REC can own and operate more than one installation. Secondary legislation specifying further operational details is still pending.

The current enabling framework for RECs shows several promising elements while others are still missing. Important voids include the lack of a transparent cost–benefit analysis of distributed energy sources, measures facilitating cooperation between DSOs and RECs, and at least partly, the access of RECs to information. Despite advancements in the regulatory framework, generous support and dedicated national funding, there are still barriers and indications of malfunctioning including red tape, time delays in granting financial support and issuing implementation rules, delays in licensing, combined with difficulties in obtaining the information needed to identify the scope of RECs, and high costs for grid connection. Many energy communities are still waiting for the regulatory process to be completed, due to postponements in implementing decrees and activating new rules that open concrete development opportunities.

RECs can count on several dedicated support measures and incentives, including a premium tariff for energy shared within a REC of EUR 110/MWh, calculated as the net difference between electricity fed into the grid and the energy taken from the grid and a partial refund of grid cost. Moreover, the Italian Recovery and Resilience Plan provides investment grants of up to 40% of the investment for RECs and jointly acting renewables self-consumers. However, grants are only available in communities with less than 5000 inhabitants and there are bureaucratic obstacles impeding smooth implementation.

Several frontrunner regions such as Piedmont have created their own legal frameworks and support schemes. In February 2022, the regional government of Lombardy announced its plans to establish 6000 new RECs within 5 years, resulting in an increase in installed PV power of almost 1300 MW. However, the pace of development of RECs is still relatively slow and varies by region. Many energy communities have been initiated top-down, either through local governments or (semi-)commercial actors. Only a few REC initiatives were actually kick-started via a bottom-up approach by either a group of citizens or an environmental NGO [14] (p. 101).

3.4. Latvia

In Latvia, energy communities are a very new concept. There is no tradition of energy cooperatives or other forms of community energy. Unlike in other areas such as management and renovation of multi-family buildings, citizens have not gained any experience in jointly investing in electricity production. Until now, the electricity sector has been dominated by centralised structures. There are few examples of collective renewable energy initiatives, mainly in the heating sector, based on solar collectors in (renovated) multi-family buildings or biomass installations. RECs in the sense of the RED II, however, are only in an embryonic stage of development. So far, there have been no pioneers in this field to illustrate a positive experience. To promote the concept of RECs, a few pilot projects have been implemented in the frame of European research programmes.

Although a general legal framework transposing the RED II provisions for RECs was adopted in July 2022 which took effect on the 1st of January 2023, full transposition of the provisions is still pending. Amendments to the Energy Act define ‘energy community’ as a single concept under which RECs and ‘electricity communities’ (the Latvian equivalent of citizen energy communities as defined in the IEMD) are subsumed. A particular energy community can fulfil either the conditions of a REC, a CEC or both. There is a large spectrum of eligible legal forms under which RECs may be organised. RECs are entitled to produce, consume, store, and sell renewable energy. Yet, government regulations further specifying the terms ‘proximity’, ‘autonomy’, and ‘effective control’ as well as the registration requirements for RECs are still pending. Amendments to the Electricity Market Act adopted in July 2022 introduced the concept of electricity sharing for collective self-consumption schemes and energy communities, while RECs were introduced as a new electricity market actor, with the same rights and obligations as other market actors. The amendments also introduced electricity sharing, i.e., members of an energy community and active users will be able to share their electricity with other members of the energy community or active users in the same building or in other types of real estate. So far, housing associations could use solar panels for collective consumption on common premises but the option to distribute electricity to individual apartments was not yet possible. This means electricity cannot be shared among the residents as individual clients. Governmental regulations complementing the general legal framework are crucial for the further development of RECs in Latvia. Their adoption is envisaged in 2023.

The enabling framework the government has to create is fragmentary and weak. Several elements are missing, and others are under consideration (e.g., differentiation of electricity distribution tariffs) or planned (e.g., technical regulations to ensure the cooperation of DSOs with RECs to facilitate energy sharing, recommendations for public authorities regarding the provision of support for energy communities and their participation in such entities). Latvia’s EU Cohesion Policy Programme for 2021–2027 envisages financial support for the installation of PV systems (including storage equipment) by cooperatives, energy communities, and households. The government also plans to provide investment support to energy communities under the multiannual operational programme of the Modernisation Fund, a dedicated funding programme to support ten lower-income EU Member States in their transition to climate neutrality. Access of RECs to risk capital and investment support ought to be improved.

The Latvian government does not currently provide any operational support for the use of RES in electricity in the form of feed-in premiums or market premiums. In 2014, the government launched a net-metering system for individual households which applies mainly to PV installations. The amendments to the Electricity Market Law of July 2022 introduced a net accounting system for both households and self-consumers of electricity produced from RES, which are legal entities. This will not only account for the amount of electricity produced from RES and consumed but will also determine the value of the electricity. Novel support schemes for RES are currently under consideration by the government. The amendments of the Energy Act envisage that the Ministry of Economics elaborates financial support programmes for RECs.

3.5. The Netherlands

The Netherlands can be regarded as one of the pioneers in the field of community energy [24] (p. 5). Like the cases of Germany and Denmark, the development of community energy initiatives in The Netherlands is connected to the 1970s oil crisis and the realisation of Dutch society that the country is highly dependent on imports of fossil fuels [60,61]. Wind cooperatives were established in the early 1980s, being the first grassroots initiatives in The Netherlands in this field [2,62]. In 2022, the total number of energy cooperatives reached 705 [63].

General legislation transposing the RED II provisions for RECs through a revision of the Dutch Energy Law is still pending. A draft version of the new Energy Law was published in July 2022. Hence, transposition has been delayed and is not complete yet. The draft Energy Law introduces the concept of an ‘energy community’ (merging the EU definitions of REC and CEC into a single concept) as a new legal entity that can be active on energy markets. In the draft legislation, these ‘energy communities’ were introduced as new market actors, with the same rights and obligations as other market parties and treated on equal footing. A REC is defined as a specific kind of ‘energy community’ that can include in its statutes the requirement that only natural persons, local authorities, or SMEs can become shareholders with effective control belonging to those shareholders located in the proximity of the renewable energy project. Specifications of key terms such as ‘effective control’, ‘proximity’, etc., will be the subject of further implementing acts. Organisations representing the interests of energy communities (e.g., Energie Samen, the umbrella organisation of Dutch energy cooperatives) call for an enabling regulatory framework for energy sharing, but this framework is still under development.

Although the transposition of the REC definition is pending, The Netherlands already has a comparatively advanced enabling framework for community energy. At the national level, the Dutch Climate Agreement of 2019 established the non-binding goal of 50% local ownership of renewable energy onshore by 2030. A potential assessment study has been carried out in 2019. Non-discriminatory treatment of RECs and access to information for RECs is ensured. It is planned that the Dutch DSOs will be legally required to carry out the transactions necessary for energy sharing and selling. The DSOs will register the different forms of energy exchange, check certain participation conditions, e.g., whether digital metering is available on a quarter-hourly basis and report the purchased, injected, and shared energy volumes to energy suppliers. The enabling framework is mainly developed at the level of the so-called ‘RES regions’ (established in 2019); however, there is only poor coordination between the regions. The provinces of South Holland, Utrecht, Limburg, and Drenthe have established a special ‘development fund’ which can be regarded as a model for other provincial governments. This fund provides start-up finance and risk capital to finance upfront costs which would be later repaid if projects prove successful. However, many municipalities (especially the smaller ones) lack the necessary information or resources to engage with local energy communities. Further capacity building for local governments, possibly with the aid of local energy cooperatives, thus appears to be a necessity to achieve the national goal of 50% local ownership in 2030.

The so-called Renewable Energy Transition Incentive Scheme (SDE++) is expected to operate until 2025 and is based on an auction process to award subsidies to renewable energy projects depending on the amount of avoided greenhouse gas emissions. There is also dedicated support (in the form of feed-in premiums) for energy cooperatives and associations of homeowners (the so-called Cooperative Energy Generation (SCE) subsidy. Eligible technologies include wind turbines, PV installations, and small hydro power schemes. National legislation should consider supporting energy communities that help with congestion management through ‘smart’ energy sharing (i.e., by balancing electricity demand and supply). Such smart energy sharing projects could, for instance, be given priority access to the grid or made eligible under the SDE++ subsidy, and incentives for participating in such projects could be offered through a reduction of value added tax (VAT).

3.6. Norway

Norway has a long-standing tradition of municipal ownership in the energy sector, while the concept of energy communities is new. There are only few energy communities based on genuine end-user participation that would fulfil the criteria of RECs pursuant to the RED II. Norway is not an EU member, but part of the European Economic Area (EEA), so that the process of implementing the RED II is not following a predefined time schedule and is not given high policy attention yet. It can take several years from the time the EU decision is made until it is included in the EEA agreement [64]. RECs have therefore not been legally defined and there are no plans for implementing a full enabling framework according to Art. 22 of the RED II to promote and facilitate the development of RECs. A promising development is that the government plans to extend the ‘plus-customer scheme’ that currently grants households rights and incentives as prosumers to facilitate joint electricity production and consumption within the same property and thus open up the ability for condominiums to become jointly acting renewables self-consumers in the sense of the RED II.

Recent stakeholder surveys revealed that regulations which limit the sharing and sale of self-produced electricity, as well as the lacking political attention at the national and local government levels represent key barriers for RECs in Norway [65]. Moreover, stakeholders highlighted the need for political support in terms of reducing regulatory and administrative burdens, increasing access to information (including systematic learning from pilot projects), and capacity development from national or local governments as well as local and national government support schemes.

The government provides investment support for household or commercial prosumers through the state enterprise Enova. Existing support schemes for RES have not been designed with energy communities in mind and do not consider the specificities of RECs. Private entities in the form of energy communities may apply for support alongside commercial actors.

The new regulations in the extended plus-customer scheme will allow for increased sharing of self-produced electricity within energy communities, but the full details are not known. The main debate concerning sharing self-produced electricity is related to prosumers’ exemption from electricity fees and the extra costs for grid companies for securing integration that entails that more costs are transferred to all customers, which may disproportionally affect those who cannot invest in household or community energy production [26]. Further, solar PV energy has only recently been acknowledged as a needed dimension in Norway’s energy transition, whereas before there has been reluctance to integrate decentralised PV solutions on a large scale due to Norway’s climatic conditions (with highest energy needs in the dark winter season). Extending the plus-customer scheme is anticipated to enable mostly PV solutions on existing buildings [65].

3.7. Poland

Energy communities in Poland are still a marginal phenomenon, and RECs and CECs, in the sense of the two relevant European directives, hardly exist to date. Legislation on energy cooperatives and so-called ‘energy clusters’ already existed before the RED II took effect. The Polish regulatory framework specifies three distinct types of collective energy initiatives: ‘energy cooperative’ (spółdzielnia energetyczna), ‘energy cluster’ (klaster energii), and ‘collective renewable energy prosumer’ (prosument zbiorowy energii odnawialnej). In 2022, the number of energy clusters officially certified by the Ministry of Energy reached 66, and the number of officially registered energy cooperatives was 2 [66]. Fifty cases have been reported where RES installations have been installed to supply multi-family buildings [32] (p. 14). The low diffusion rates of energy community projects can be explained by strong economic–political carbon lock-in due to the dependence on domestic coal [67], the dominance of state-owned incumbents from the fossil fuel industry [68], a lack of appropriate renewable energy strategies in Polish municipalities [32] (p. 14), and the negative connotations associated with cooperatives and other forms of collective ownership during the socialist period [66].

Even though the transposition deadline passed in June 2021, the provisions for RECs contained in the RED II have not been incorporated yet in domestic legislation. So far, the Polish Law on Renewable Energy Sources includes only provisions for energy cooperatives and energy clusters. However, energy clusters which were introduced already in 2016 do not comply with the EU definition of RECs. These clusters are not legal entities but are based on civil law contracts. The purpose of an energy cluster is the production and balancing of demand and distribution, or trade of energy within the distribution network. Often, local authorities and businesses are the key drivers behind the establishment of energy clusters in Poland with a very low level of citizen participation [68]. For energy cooperatives, there are several restrictions in terms of maximum installed capacity (max. 10 MW), and energy use (70% of the cooperative’s and its members’ demand must be covered by the respective RES installation(s)). Energy cooperatives cannot sell the generated energy to a non-member entity.

In October 2021, the government introduced definitions for collective and virtual prosumers with support-based net billing [69], but to date no collective prosumer installations have been established. Draft legislation intended to transpose several provisions of the RED II includes a few legal amendments on ‘energy clusters’ but does not directly transpose the provisions for RECs. Poland has a weak enabling framework for RECs and most elements required by the RED II are still lacking or underdeveloped. Access to information and financing is poor. The cost–benefit analysis and assessment of barriers and potentials are missing. The lack of attractive economic incentives and the continuously changing legal framework led to passivity among local communities, municipalities, and civil society, hampering their engagement in RECs and the creation of respective business plans. A key barrier to the development of energy sharing and collective prosumership is the poor technical condition of distribution and transmission networks.

However, some positive elements could be found. There have been several initiatives by the Senate to remove administrative barriers for energy cooperatives. In the “Energy Policy of Poland with a horizon to 2040”, energy communities are presented as an important means of empowering and stimulating electricity consumers [70]. The strategic document assumes that the number of ‘sustainable energy areas’ at the local level (i.e., energy clusters, energy cooperatives) will reach 300 by 2030. Poland also aims to provide pre-investment, investment, and capacity-building support for energy communities including energy clusters and energy cooperatives through its Recovery and Resilience Plan [71].

Auctions are the main support scheme for RES-based electricity but no special rules or preferential treatment for energy communities or energy cooperatives could be identified.

3.8. Portugal

In Portugal, community energy initiatives were relatively common in the early 20th century and typically associated with small hydropower plants and local electricity distribution networks. With the centralisation of electricity generation, however, community solutions lost relevance [72]. In recent years, a (re-)emergence of collective energy initiatives can be observed, although the development of RECs in the sense of the RED II is still limited.

Portugal was among the first Member States to transpose the RED II [45]. Already in 2019, the government introduced a legal framework for collective renewables self-consumption and RECs (Comunidades de Energia Renovável) by Decree Law 162/2019, partially transposing the RED II provisions for RECs. The legal definition was recently adjusted by the Decree Law no 15/2022. RECs are explicitly entitled to produce, consume, store, and sell renewable energy. Energy sharing among REC members is also allowed. The Decree Law no 15/2022 provided some clarification regarding the principle of ‘proximity’ and the conditions for energy sharing. Although the transposition of the legal framework for RECs is relatively advanced, most of the provisions for RECs have been literally transposed from the RED II without adding sufficient specifications to facilitate the operationalisation of the concept. Provisions regarding ‘autonomy’, ‘effective control’, and ‘primary purpose’ are still abstract.

Moreover, the transposition of key elements of the enabling framework for RECs is still pending. There are manifold barriers including a lack of information, poor access to financing, and the burdensome and lengthy licensing procedures. As in most other countries under scrutiny, the integration of provisions for RECs into spatial planning and urban infrastructure is missing. The same applies to the transparent cost–benefit analysis of distributed energy sources. Some steps have been taken to overcome the barriers for RECs, namely through the simplification of procedures, the launch of a dedicated support scheme for RECs, and guidance to facilitate the implementation of REC projects. RECs and collective renewables self-consumption schemes are—to different extents—exempt from paying specific elements of the network charges called CIEG (Custos de Interesse Económico Geral). These represent the costs of energy policy, environmental or general economic interests associated with the production of electricity, and the costs of the sustainability of markets (Despacho n. 6453/2020). For collective self-consumption schemes and RECs, 100% of the CIEG is discounted. Additionally, the provision of dedicated support to RECs, through the creation of a self-consumption and RECs support office can be assessed positively. However, there is a need to further simplify the licensing procedures and to disclose and disseminate information on ongoing pilot projects, to increase awareness and trust in the concept. Moreover, there is a need to empower local authorities in their role as key enablers of RECs, e.g., with specialised training courses. The establishment of one-stop-shops by local governments and other local entities (such as energy agencies) could mitigate the lack of information and capacity of citizens and SMEs.

RECs do not have access to specific rules or special treatment in the frame of the existing support schemes (auctions) for RES-based electricity. However, in June 2022, the national government opened a call to support the implementation of RECs and collective self-consumption schemes via investment grants, financed through the Recovery and Resilience Plan.

3.9. Spain

In Spain, energy cooperatives have a long historical tradition. Sciullo et al. [44] identified two waves of cooperative development. The first wave started in the end of the 19th century when communities in peripheral regions started to collectively supply electricity to their homes and enterprises mainly based on of small hydro power plants. A second wave could be observed after 2010, when several cooperatives were established. They focussed on the retailing of electricity from RES, the main motivation being environmental and social concerns inspired by other examples in Europe.

Already since 2015, Spain has an advanced regulatory framework for collective self-consumption on a building/neighbourhood level. The country is one of the few Member States that allow collective self-consumption schemes using the public grid. Through Royal Decree Law no 23/2020 from 23 June 2020, the government introduced the definition of RECs, which is mostly a literal transposition of the EU definition contained in the RED II, without any further specifications of the governance principles, rights, duties, and possible market activities. Therefore, stakeholders interested in developing RECs face considerable regulatory uncertainty and often resort to the legal framework for collective self-consumption. The current regulatory framework can be interpreted as a hybrid model of collective self-consumption and RECs [73]. However, there are several limitations in terms of grid connection (only low voltage), maximum installed capacity (100 kW), and participation radius which has been recently expanded from 500 m to 2000 m through Royal Decree Law no 18/2022 from 18 October 2022. Furthermore, there is no concrete delimitation of the types of legal entities that could be used to develop RECs, and no regulatory authority has been given powers to oversee compliance with the definition of a REC. Consequently, there are no operating communities in Spain that correspond precisely to the EU definition of CECs or RECs [11] (p. 73). There is an urgent need to transpose the relevant provisions of RED II fully and correctly, including energy sharing within RECs.

The national government and several regions have also taken concrete steps to develop an enabling framework for RECs. Particularly, access of RECs to financing has been facilitated. Spain has established several dedicated funding lines for RECs covering different phases of REC development. In total, EUR 100 million has been mobilised through the Recovery, Transformation and Resilience Plan to promote, support, and develop RECs. So far, four calls for incentives for unique energy community projects [74] have been launched, as well as a dedicated call for grants to create or support Community Transformation Offices for the promotion and dynamisation of energy communities [75]. Furthermore, many regional and local authorities are utilising resources from the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) to promote and develop RECs in their territories. This assistance normally includes subsidies and/or technical assistance to incipient initiatives. Poor access to information represents a key barrier for many REC initiatives, but several steps have been taken to improve the situation. In contrast to most other countries examined, the government has taken significant steps to develop a cost–benefit analysis for distributed generation. Currently for collective self-consumption schemes, no grid fees are charged for the electricity shared within the communities. The creation of a legal and enabling regulatory framework is primarily a responsibility of the national policy actors and administrations; whereas, for the provision of financial assistance as well as legal/technical support and advice, all levels of government can (and already do) take action. As an illustrative example, the Royal Decree Law no 18/2022 incorporated concrete measures towards administrative simplification for any small renewable generation facility (up to 500 kW). Regional and local support varies greatly, with some territories not receiving any kind of support (apart from national) and some others having very capable and engaged local and regional administrations in terms of providing administrative, technical, and financial assistance.

Through the Royal Decree Law no 23/2020, the central auctions system promoting the use of RES in the electricity sector was amended. The amendments aim, inter alia, to promote the role of energy communities. Moreover, the Spanish government took measures to take the specificities of RECs into account in the design of the auctions scheme. As a pre-qualification requirement, participants in the auctions must present a plan for local citizen participation. Moreover, in the recent auctions, special bidding windows have been created exclusively for citizen-led, distributed PV generation projects.

4. Discussion

Our assessment revealed parallels but also remarkable differences between the countries analysed in terms of transposition performance. This is not surprising, as the same European rules must be transposed and applied by countries with different historical, cultural, socio-economic, institutional, and political backgrounds as well as energy systems. In the following, the findings will be compared and discussed with a focus on timeliness and completeness. In most cases, it is difficult to assess the substantive correctness of transposition because specifications of indefinite legal terms and further legal, regulatory, and technical details are pending. Moreover, there are a lack of objective criteria or guidance developed by EU institutions by which the correctness of transposition might be evaluated on a solid basis. The section will also present the results of the quantitative assessment of transposition completeness.

4.1. Comparing Timeliness of Transposition

Our results show that none of the analysed EU countries transposed the relevant EU provisions for RECs in a timely manner (i.e., by 30 June 2021). Norway is not an EU member and the RED II is still under review by the EEA. Hence, the process of implementing the RED II in Norway is not following a predefined schedule. Moreover, the implementation does not receive high policy attention yet. In several countries including Italy and Portugal, transposition started comparatively early but is still incomplete. It is striking that in pioneer countries such as Germany and The Netherlands where energy cooperatives and other forms of energy communities are already well established, the transposition process started comparatively late and was slow. One might expect that for countries that already have policies, regulations, and support schemes in place to support energy communities and other non-commercial actors in the energy market, the transposition of the provisions on RECs provides an opportunity to upgrade and expand the existing regulatory and enabling framework [10]. The transposition would therefore take place without any major delays or frictions, all the more so as Germany and The Netherlands generally exhibit low transposition deficits and low-to-average transposition delays [76].

However, in Germany the previous federal government did not take any steps to bring the pre-existing definition of ‘citizen energy companies’ in line with the RED II or to further develop the existing enabling framework as required by the RED II. Only under the current government has progress been made. In The Netherlands, the transposition of the RED II provisions for RECs is even slower. The final adoption of the Energy Act that incorporates the European rules for RECs and CECs into national legislation is still pending. By contrast, in countries where community energy has been less advanced so far, such as in Italy or Spain, or almost non-existing, for example, Portugal, the transposition started much earlier. Italy is particularly striking as the country currently ranks last in the EU Single Market Scoreboard in terms of transposition delays with an overall average transposition delay of 20 months compared to an EU average of 8.6 months [76]. In Portugal, the efforts are concentrated on the transposition of the REC definition and to a lesser extent to the creation of an enabling framework. Another notable case is Poland, where the government has not taken any steps so far to transpose the RED II provisions for RECs, although the country generally shows average performance in terms of transposition timeliness [76].

4.2. Comparing Completeness of Transposition: Definitions, Rights, and Market Activities

None of the nine analysed countries have transposed the definitions, rights, and possible market activities completely. Norway is not considered here further as the RED II is still under review by the EEA/EFTA.

Even though the countries under scrutiny (except The Netherlands, Norway, and Poland) have incorporated definitions of RECs into their legal frameworks, these remain partly rather general and provide little detail (if any) on the various governance principles such as ‘effective control’, ‘proximity’, or ‘autonomy’. Many governments have used a “copy out” approach [77], i.e., a literal transposition of the provisions for RECs.

Flanders, Germany, Italy, Portugal, and Spain can be considered as relatively advanced in transposing and partly also substantiating the provisions compared to other countries. However, in some Member States (e.g., Italy, Spain) there are geographical and capacity restrictions for collective self-consumption schemes and RECs. The German experience reveals the pitfalls of ill-defined concepts being vulnerable to misuse and the importance of waterproof definitions [57].

In Flanders, Italy, Latvia, The Netherlands, Portugal, and Spain, RECs are or will be explicitly entitled to produce, consume, store, and sell renewable energy replicating the wording of the RED II. Flanders, Italy, and to a certain extent, Spain can be regarded as frontrunners in transposing and are already practically implementing energy sharing, while the other countries are still lacking proper regulatory frameworks for energy sharing. Italy provides both a regulatory framework and economic incentives for energy sharing. Although Germany has made progress in accommodating the definition of RECs after the change in government, the responsible Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action has refrained from introducing a framework for energy sharing. Access of RECs to suitable energy markets has been ensured in most countries, but needs improvement for some segments, including access to flexibility markets.

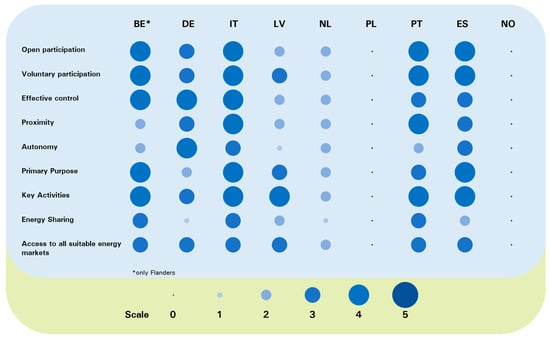

Figure 3 illustrates the transposition performance of the nine countries as of mid-July 2022 with regard to definitions, rights, and market activities of RECs. Poland and Norway are not considered due to the lacking transposition.

Figure 3.

Comparing completeness of transposition: definitions, rights, and market activities of RECs (Source: Authors’ elaboration). See Table 2 for the calibration of the different scales.

4.3. Comparing Completeness of Transposition: Enabling Frameworks for RECs

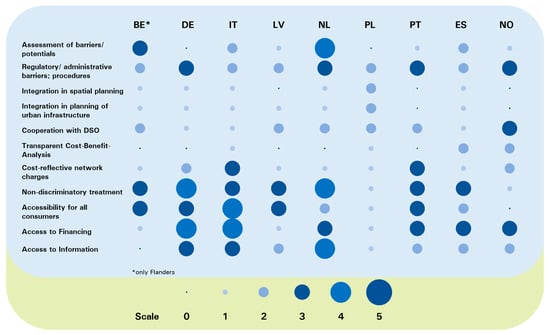

None of the nine countries have developed an enabling framework for RECs that fully or largely complies with the minimum requirements listed in the RED II. In most countries, these enabling frameworks are still underdeveloped or fragmentary. Critical bottlenecks include technical, geographical, or capacity restrictions for RECs; lengthy and burdensome permitting/licensing procedures; lack of information; and lack of start-up financing and risk capital. It can be assumed, however, that recent policy developments at the European level including the Council Regulation (EU) 2022/2577 which aims to accelerate the deployment of renewable energy and planned amendments to the Renewable Energy Directive (RED III) will help to speed up the permit-granting processes for RES projects in all EU Member States. Norway, not being a member of the EU, has some elements of an enabling framework for RECs in place, although these have not been developed with the RED II in mind.

Several countries under scrutiny have ignored the requirement to assess barriers and development potentials of RECs in their territories (see also Figure 4). In most cases, an urgent need for effective measures to facilitate the cooperation of RECs with the DSOs has been identified to enable energy sharing. Only in a few cases did the authors find (draft) provisions aimed to facilitate such a cooperation. Moreover, in most countries analysed there is a need for intermediaries, advisory services, and one-stop-shops providing neutral information, as well as administrative, legal, organisational, and financial assistance to RECs, but also to citizens, municipalities, and SMEs. Another transposition gap identified in all countries, except for Spain and to a certain extent Norway, is the lack of a transparent cost–benefit analysis for distributed generation to ensure adequate, fair, and balanced system cost sharing. However, Italy and Portugal took measures to ensure that RECs are subject to cost-reflective network charges including exemptions from certain network cost elements. Access to financing seems to be a problem in some Member States such as Latvia and Poland, but also in Flanders (Belgium). In other countries, despite existing investment and/or operational support, there is a lack of start-up financing and risk capital. Nevertheless, the findings show that novel financing instruments including revolving funds are increasingly being designed (e.g., Germany, The Netherlands) to overcome this barrier. Such funds are based on grant-to-loan schemes and cover planning and development costs in the start-up phase. Funding would later be repaid if the REC project proves successful. In Italy, Poland, Portugal, and Spain, the Recovery and Resilience Plans which aim to overcome the economic consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic, incorporate financial support for RECs with specific rules and funding streams. Accessibility to RECs for all consumers including low-income or vulnerable households is explicitly addressed in Italy, but implicitly in the other analysed countries. However, dedicated policy measures to facilitate the access of those groups to financing and information are still scarce. Measures ensuring that RECs are considered in spatial and urban planning lack in all countries. The creation of an enabling framework for RECs pursuant to the RED II is a multi-level governance task [23,78], and the decentralisation of authority and resources to sub-national and local governments are critical for effective enabling frameworks [68].

Figure 4.

Comparing completeness of transposition: enabling frameworks for RECs (Source: Authors’ elaboration). See Table 2 for the calibration of the different scales.

Figure 4 illustrates the transposition performance of all nine countries as of mid-July 2022 with regard to the enabling framework for RECs.

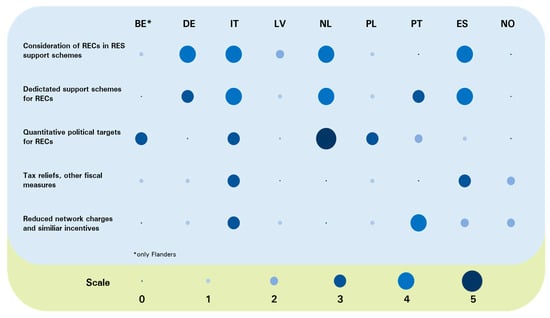

4.4. Comparing Completeness of Transposition: Consideration of RECs in Target Setting and Support Scheme Designs

Germany, Italy, The Netherlands, and Spain consider the specificities of RECs when designing support schemes for RES. The present German government decided to make use of the revised European State Aid Guidelines (2022/C 80/01) and exempted projects of RECs below certain capacity thresholds from the obligation to take part in auctions, while Spain started to create special bidding windows for citizen-led initiatives in its auction system. The Netherlands offers feed-in premiums for energy cooperatives and associations of homeowners. In the nine countries analysed, support schemes and economic incentives specifically targeting RECs are mostly lacking or are under preparation. Nevertheless, several promising policies and measures which might provide orientation for other EU Member States were identified. These entail economic incentives for RECs, including premium tariffs for shared energy in Italy, citizen/community energy funds providing start-up financing for RECs in The Netherlands and Germany, and reduced network charges in Italy. The authors found only a few examples where the governments use tax reliefs and other fiscal measures to support RECs.

The study sought out examples of quantitative target setting in some countries, at the national or regional level (Flanders, Italy, The Netherlands, and Poland). Figure 5 shows the graphical translation of the transposition performance of the nine countries as of mid-July 2022 regarding target setting and consideration of the specificities of REC in the design of support schemes.

Figure 5.

Comparing completeness of transposition: consideration of RECs in target setting and support scheme designs (Source: Authors’ elaboration). See Table 2 for the calibration of the different scales.

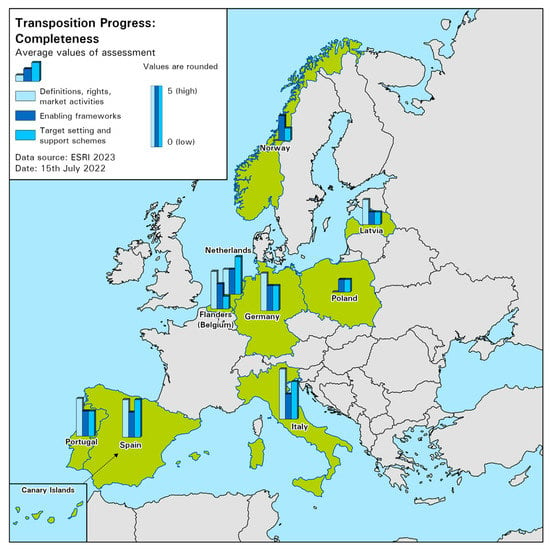

Figure 6 provides an overview of the transposition performance illustrating the completeness of transposition for all three analytical categories. The bars are based on average aggregate values for each of the analysed categories.

Figure 6.

Overview of transposition completeness in the three analytical sections per country (Source: Authors’ elaboration).

4.5. Interpreting Transposition Delays, Gaps, and Cross-Country Variation in Transposition Performance

In the following, tentative interpretations regarding the reasons for the variation in transposition timeliness and completeness are drawn. The authors are aware that an analysis of transposition performance one year after the formal transposition deadline might be premature, especially taking into account that according to the EU Commission’s current Single Market Scoreboard, the EU-27 average transposition delay in December 2021 amounted to 8.6 months [76]. Moreover, it should also be considered that transposition of the RED II is still in progress, secondary legislation is being developed in most of the analysed countries, and it is difficult to evaluate substantive correctness. Hence, these interpretations are preliminary.

So far, only a few comparative studies reflecting upon the transposition of the Clean Energy Package including the provisions for RECs made explicit statements about the reasons for variation in the transposition performance between EU Member States. According to Sciullo et al. [44] (p. 10), who analysed transposition in six EU Member States at an early stage, differences in transposition performance can be explained “by different political and governing structures inside countries that offer an assorted picture of the planning policies in the energy field including the number of decision-making actors implied in the adoption of the measure.” Roberts [36] (p. 41) pointed to circumstances such as upcoming national elections, and the redirection of resources towards dealing with COVID-19, which might explain transposition delays. Referring to the case of Germany, Holstenkamp [10] emphasised that a well-developed community energy sector means that new regulations must fit the existing types of ownership and the legal or social concepts available (“institutional fit”). Further, the author stressed that due to the existence and size of the community energy sector in Germany, the government may interpret the EU regulations as addressing latecomer countries rather than Germany.

To interpret the findings, the authors of this article refer to the results of European implementation research (for an overview, see [3]). Research on how EU policies are put into practice in the Member States has proliferated over the last three to four decades. Within this branch of research, the transposition of EU directives has received much scientific attention, while application and enforcement were studied to a lesser extent [3]. Scholars have analysed numerous potential variables to explain disparate transposition records across countries and policy areas. While there is a large number of quantitative and qualitative studies analysing the transposition of EU directives in various policy sectors on an aggregate level, there are fewer studies which analyse timeliness, completeness, and correctness of transposition on a disaggregate level focusing on individual provisions within a directive. Research findings suggest that the transposition of EU directives varies across sectors [79,80]. Moreover, there is also variation in Member States’ compliance with different provisions of EU directives [50].

EU implementation research has identified a broad variety of influencing factors, although no consistent theoretical approach or a commonly agreed explanatory model has yet been developed [52] (p. 40), [80] (p. 5), [81] (p. 13). Empirical results of quantitative and qualitative research are often inconclusive or even contradictory. Scholars made several attempts to integrate different explanatory factors into theoretically consistent models [80]. In his comprehensive literature review, Treib [3] scrutinised multiple explanatory variables analysed in the literature for their evidence robustness. He differentiated between EU-level factors, domestic factors related to Member States’ willingness to comply, and domestic factors related to Member States’ capacity to comply, and argued that domestic factors seem to mainly explain variations of Member States’ transposition performance. Following Treib’s analysis, a table has been compiled providing an overview of key factors with varying degrees of evidence robustness to explain transposition performance (see Table 3). While Treib [3] subsumed characteristics of a directive to be transposed under EU-level factors, the authors suggest to treat these characteristics as their own fourth category.

Table 3.

Factors influencing transposition performance (based on [3]).

Treib [3] concluded that the level of discretion granted to Member States has a significant effect on the transposition, with directives granting more discretion being easier to transpose since they give Member States more opportunities to adapt EU policies to domestic conditions. The most widespread and systematic effects relate to the reform requirements associated with individual directives. Moreover, party politics and changes of government claim certain explanatory power as well as the degree of fit between the policy goals enshrined in European legislation and pre-existing domestic policy legacies. Structural factors determining the capacity of Member States to process the legal incorporation of directives into national law play a key role in the transposition performance. This primarily relates to administrative capabilities and to the (sector- or even case-specific) number of veto players involved in law-making processes (e.g., coalition partners, parliamentary involvement).

Summarising the case of Germany, this article supports the finding that the partisan factor can play a significant role. The change of government led to a dynamisation of the transposition process. The new government brought the pre-existing definition of ‘citizen energy company’ in line with the RED II and the concept of RECs, improved access to start-up financing, and exempted renewable energy projects of citizen energy companies below certain capacity thresholds from the obligation to participate in auctions. The German case also confirms the finding that if a Member State has legislation in place resembling the directive’s provisions, a smooth transposition cannot be necessarily taken for granted. Even if the existing legal regime needs a relatively minor change in response to the new directive, this is likely to incur non-negligible adaptation costs [50] (p. 718), [82] (p. 698). The fact that the government refrained from transposing energy sharing illustrates the importance of the institutional fit and the need to re-align the provisions for RECs with the overall electricity market design.

One should also keep in mind, and this refers to all the nine countries analysed, that successful implementation of the provisions on RECs will change established actor constellations, disrupting ownership structures, market shares, and power relations. Due to their strong position in the energy systems, incumbents may influence the transposition of the RED II in ways that can be hidden [35]. Therefore, particularly in the energy sector, interest group influence deserves attention as a potential explanatory factor. Conversely, consequent unbundling, far reaching market liberalisation, and decentralisation of the energy sector might be conducive for the advancement of energy communities [44] and facilitate timely transposition and implementation.