Does Corporate Social Responsibility Moderate the Nexus of Organizational Culture and Job Satisfaction?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Job Satisfaction

2.2. Organizational Culture

2.3. Corporate Social Responsibility

2.4. Organizational Culture and Job Satisfaction

2.5. Corporate Social Responsibility and Job Satisfaction

2.6. Role of CSR between OC and JS

3. Research Methodology

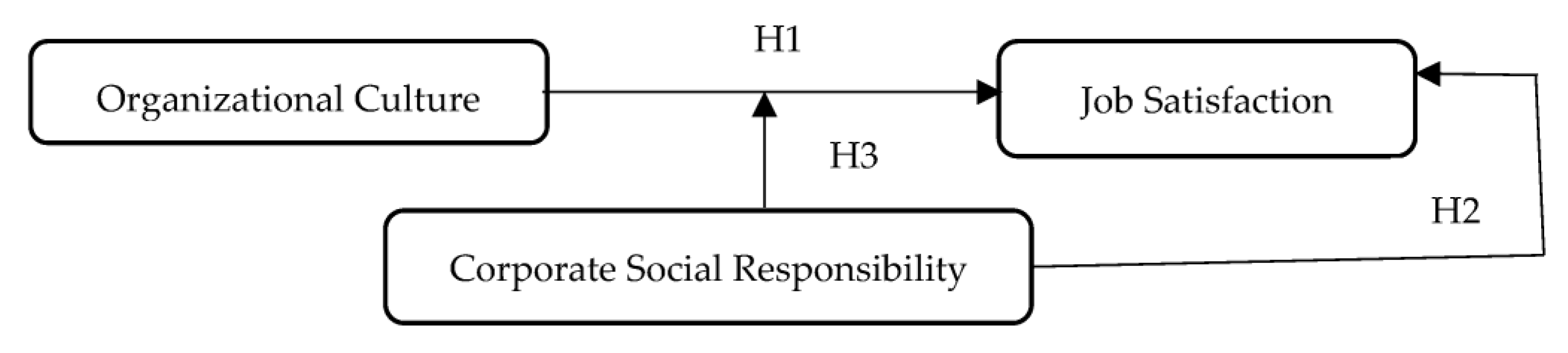

3.1. Research Framework

3.2. Measurement Items

4. Data Analysis

Sample Size and Data Collection

5. Results

5.1. Method of Testing Common Bias

5.2. Estimation of Measurement Model (Reliability and Validity)

5.3. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

6. Discussion

7. Limitations and Future Research

8. Theoretical and Managerial Implications

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Budur, T.; Demir, A. Leadership perceptions based on gender, experience, and education. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Educ. Stud. 2019, 6, 142–154. [Google Scholar]

- Kaliski, B.S. Views on the Future of Business Education: Responses to Six Critical Questions. Delta Pi Epsil. J. 2007, 49, 9–14. [Google Scholar]

- Zardasht, P.; Omed, S.; Taha, S. Importance of HRM Policies on Employee Job Satisfaction. Black Sea J. Manag. Mark. 2020, 1, 49–57. [Google Scholar]

- Paais, M. Effect of work stress, organization culture and job satisfaction toward employee performance in Bank Maluku. Acad. Strateg. Manag. J. 2018, 17, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Suher, I.K.; Bir, C.S.; Yapar, A. The effect of corporate social responsibility on employee satisfaction and loyalty: A research on Turkish employees. Int. Res. J. Interdiscip. Multidiscip. Stud. (IRJIMS) 2017, 7969, 87–105. [Google Scholar]

- Woolliams, P.; Moseley, T. Organisation Culture and Job Satisfaction; Earlybrave: Chelmsford, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Appelbaum, P.S.; Lidz, C.W.; Grisso, T. Therapeutic misconception in clinical research: Frequency and risk factors. IRB Ethics Hum. Res. 2004, 26, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, S.; Kumar, S.P. Organizational culture as a moderator between affective commitment and job satisfaction: Empirical evidence from Indian public sector enterprises. Int. J. Public Sect. Manag. 2018, 31, 184–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanusi, F.A.; Johl, S.K. A proposed framework for assessing the influence of internal corporate social responsibility belief on employee intention to job continuity. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 2437–2449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Heo, C.Y. Corporate social responsibility and customer satisfaction among US publicly traded hotels and restaurants. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2009, 28, 635–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozes, M.; Josman, Z.; Yaniv, E. Corporate social responsibility organizational identification and motivation. Soc. Responsib. J. 2011, 7, 310–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatma, M.; Rahman, Z.; Khan, I. Building company reputation and brand equity through CSR: The mediating role of trust. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2015, 33, 840–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.L.; Woo, E.; Uysal, M.; Kwon, N. The effects of corporate social responsibility (CSR) on employee well-being in the hospitality industry. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 1584–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguinis, H.; Glavas, A. What we know and don’t know about corporate social responsibility: A review and research agenda. J. Manag. 2012, 38, 932–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonini, S.; Swartz, S. Bringing Discipline to Your Sustainability Initiatives; McKinsey & Company: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- You, C.S.; Huang, C.C.; Wang, H.B.; Liu, K.N.; Lin, C.H.; Tseng, J.S. The relationship between corporate social responsibility, job satisfaction and organizational commitment. Int. J. Organ. Innov. 2013, 5, 65–77. [Google Scholar]

- Manzoor, F.; Wei, L.; Nurunnabi, M.; Subhan, Q.A.; Shah, S.I.A.; Fallatah, S. The impact of transformational leadership on job performance and CSR as mediator in SMEs. Sustainability 2019, 11, 436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazim, Y.Y.; Azizan, N.A.B.; Sorooshian, S. How are the Performance of Small Businesses Influenced by HRM Practices and Governmental Support? Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 2015, 6, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S. Examining the relationship between sme’s organizational factors and employee creativity. Acad. Strateg. Manag. J. 2021, 20, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, S. Exploring the firm’s influential determinants pertinent to workplace innovation. Probl. Perspect. Manag. 2021, 19, 272–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghardallou, W. Corporate sustainability and firm performance: The moderating role of CEO education and tenure. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allui, A.; Pinto, L. Non-financial benefits of corporate social responsibility to Saudi companies. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ghazali, B.M.; Sohail, M.S.; Jumaan, I.A.M. CSR perceptions and career satisfaction: The role of psychological capital and moral identity. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldhuwaihi, A.; Shee, H.K.; Stanton, P. Organisational culture and the job satisfaction-turnover intention link: A case study of the Saudi Arabian banking sector. World 2012, 2, 127–141. [Google Scholar]

- Berglund, V.; Johansson Sevä, I.; Strandh, M. Subjective well-being and job satisfaction among self-employed and regular employees: Does personality matter differently? J. Small Bus. Entrep. 2016, 28, 55–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauzi, A.A.; Suryani, T. Measuring the effects of service quality by using CARTER model towards customer satisfaction, trust and loyalty in Indonesian Islamic banking. J. Islam. Mark. 2019, 10, 269–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, T.A.; Weiss, H.M.; Kammeyer-Mueller, J.D.; Hulin, C.L. Job attitudes, job satisfaction, and job affect: A century of continuity and of change. J. Appl. Psychol. 2017, 102, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarnaccia, C.; Scrima, F.; Civilleri, A.; Salerno, L. The role of occupational self-efficacy in mediating the effect of job insecurity on work engagement, satisfaction and general health. Curr. Psychol. 2018, 37, 488–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanaysha, J.; Tahir, P.R. Examining the effects of employee empowerment, teamwork, and employee training on job satisfaction. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 219, 272–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siengthai, S.; Pila-Ngarm, P. The interaction effect of job redesign and job satisfaction on employee performance. In Evidence-Based HRM: A Global Forum for Empirical Scholarship; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bradford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S. Workplace spirituality and unethical pro-organizational behavior: The mediating effect of job satisfaction. J. Bus. Ethics 2020, 161, 687–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, E.A. The nature and causes of job satisfaction. In Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psycho; Dunnette, M.D., Ed.; Rand McNally: Chicago, IL, USA, 1976; pp. 1297–1349. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, P.K.; Rafiq, M.; Saad, N.M. Internal marketing and mediating role of organizational competencies. Eur. J. Mark. 2003, 37, 1221–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barakat, S.R.; Isabella, G.; Boaventura, J.M.G.; Mazzon, J.A. The influence of corporate social responsibility on employee satisfaction. Manag. Decis. 2016, 54, 2325–2339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengupta, A.S.S.; Yavas, U.; Babakus, E. Interactive effects of personal and organizational resources on frontline bank employees’ job outcomes. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2015, 33, 884–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glavas, A.; Kelley, K. The effects of perceived corporate social responsibility on employee attitudes. Bus. Ethics Q. 2014, 24, 165–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Roeck, K.; Maon, F. Building the theoretical puzzle of employees’ reactions to corporate social responsibility: An integrative conceptual framework and research agenda. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 149, 609–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, P.M. Exchange and Power in Social Life; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, D.A. Does serving the community also serve the company? Using organizational identification and social exchange theories to understand employee responses to a volunteerism program. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2010, 83, 857–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackman, J.R.; Oldman, G.R. Development of the Job Diagnostic Survey. J. Appl. Psychol. 1975, 60, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warr, P.B. Age and occupational well-being. Psychol. Ageing 1992, 7, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, A.M.; Christianson, M.K.; Price, R.H. Happiness, Health, or Relationships? Managerial Practices and Employee Well-Being Tradeoffs. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2007, 21, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spector, P.E. Job Satisfaction: Application, Assessment, Causes, and Consequences; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1997; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, M.A.; Laschinger, H.K.S.; Andrusyszyn, M.A. Clinical educators’ empowerment, job tension, and job satisfaction: A test of Kanter’s theory. J. Nurses Prof. Dev. 2006, 22, 78–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, W.W. A Study of Archeology; American Anthropological Association; Literary Licensing, LLC: Arlington, TX, USA, 1948; Volume 69. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede, G. Empirical models of cultural differences. In Contemporary Issues in Cross-Cultural Psychology; Bleichrodt, N., Drenth, P.J.D., Eds.; Swets & Zeitlinger Publishers: Lisse, The Netherlands, 1991; pp. 4–20. [Google Scholar]

- Deshpande, R.; Webster, F.E., Jr. Organizational culture and marketing: Defining the research agenda. J. Mark. 1989, 53, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korschun, D.; Bhattacharya, C.B.; Swain, S.D. Corporate social responsibility, customer orientation, and the job performance of frontline employees. J. Mark. 2014, 78, 20–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, P.; Lee, N. Corporate Social Responsibility Doing the Most Good for Your Company and Your Cause; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- De Roeck, K.; Farooq, O. Corporate social responsibility and ethical leadership: Investigating their interactive effect on employees’ socially responsible behaviors. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 151, 923–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.M.; Park, S.Y.; Lee, H.J. Employee perception of CSR activities: Its antecedents and consequences. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 1716–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkington, J. 25 years ago I coined the phrase “triple bottom line.” Here’s why it’s time to rethink it. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2018, 25, 2–5. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, X.; Bhattacharya, C.B. The debate over doing good: Corporate social performance, strategic marketing levers, and firm-idiosyncratic risk. J. Mark. 2009, 73, 198–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheidler, S.; Edinger-Schons, L.M.; Spanjol, J.; Wieseke, J. Scrooge posing as Mother Teresa: How hypocritical social responsibility strategies hurt employees and firms. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 157, 339–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWilliams, A.; Siegel, D. Corporate social responsibility: A theory of the firm perspective. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2001, 26, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matten, D.; Moon, J. “Implicit” and “explicit” CSR: A conceptual framework for a comparative understanding of corporate social responsibility. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2008, 33, 404–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguinis, H. Organizational responsibility: Doing good and doing well. In APA Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology, Vol 3: Maintaining, Expanding, and Contracting the Organization; Zedeck, S., Ed.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2011; pp. 855–879. [Google Scholar]

- Shurbagi, A.M.A.; Zahari, I. The relationship between transformational leadership, job satisfaction and the effect of organizational culture in National Oil Corporation of Libya. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Management, Applied and Social Sciences (ICMASS’2012), Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 24–25 March 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, M.L.; Su, S.H.; Chang, J.K.; Tsai, D.S.; Chen, C.H.; Wu, C.I.; Li, L.J.; Chen, L.J.; He, J.H. Monolayer MoS2 heterojunction solar cells. ACS Nano 2014, 8, 8317–8322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belias, D.; Koustelios, A.; Vairaktarakis, G.; Sdrolias, L. Organizational culture and job satisfaction of Greek banking institutions. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 175, 314–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avram, E.; Ionescu, D.; Mincu, C.L. Perceived safety climate and organizational trust: The mediator role of job satisfaction. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 187, 679–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menguc, B.; Ozanne, L.K. Challenges of the “green initiative”: A natural resource-based approach to the environmental orientation-business performance relationship. J. Bus. Res. 2005, 58, 430–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashforth, B.E.; Harrison, S.H.; Corley, K.G. Identification in organizations: An examination of four fundamental questions. J. Manag. 2008, 34, 325–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Roeck, K.; Marique, G.; Stinglhamber, F.; Swaen, V. Understanding employees’ responses to corporate social responsibility: Mediating roles of overall justice and organisational identification. Int. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2014, 25, 91–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, S.D.; Terlutter, R.; Diehl, S. Talking about CSR matters: Employees’ perception of and reaction to their company’s CSR communication in four different CSR domains. Inter. Int. J. Advert. 2020, 39, 191–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raineri, N.; Paillé, P. Linking corporate policy and supervisory support with environmental citizenship behaviors: The role of employee environmental beliefs and commitment. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 137, 129–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauman, C.W.; Skitka, L.J. Corporate social responsibility as a source of employee satisfaction. Res. Organ. Behav. 2012, 32, 63–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, A.; Alam, I.; Faridi, M.R.; Ayub, S. Corporate social irresponsibility towards the planet: A study of heavy metals contamination in groundwater due to industrial wastewater. Soc. Responsib. J. 2019, 16, 793–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentine, S.; Fleischman, G. Ethics programs, perceived corporate social responsibility and job satisfaction. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 77, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlachos, P.A.; Panagopoulos, N.G.; Rapp, A.A. Feeling good by doing good: Employee CSR-induced attributions, job satisfaction, and the role of charismatic leadership. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 118, 577–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riordan, C.M.; Gatewood, R.D.; Bill, J.B. Corporate image: Employee reactions and implications for managing corporate social performance. J. Bus. Ethics 1997, 16, 401–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, H.C.; El’fred, H.Y. Organisational ethics and employee satisfaction and commitment. Manag. Decis. 2004, 42, 677–693. [Google Scholar]

- Reddy, P.S.; Venkat, N.; Nagabhaskar, M.; Subbareddy, D. An empirical study of octapace culture and organizational commitment. MIJBR 2018, 5, 38–45. [Google Scholar]

- Upham, S.P. A model for giving: The effect of corporate charity on employees. J. Corp. Citizsh. 2006, 22, 81–90. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, D.A.; Willness, C.R.; Madey, S. Why are some job seekers attracted to socially responsible companies? Testing underlying mechanisms. In Academy of Management Proceedings; Academy of Management: Briarcliff Manor, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Rupp, D.E.; Ganapathi, J.; Aguilera, R.V.; Williams, C.A. Employee reactions to corporate social responsibility: An organizational justice framework. J. Organ. Behav. Int. J. Ind. Occup. Organ. Psychol. Behav. 2006, 27, 537–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greening, D.W.; Turban, D.B. Corporate social performance as a competitive advantage in attracting a quality workforce. Bus. Soc. 2000, 39, 254–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galbreath, J. Drivers of corporate social responsibility: The role of formal strategic planning and firm culture. Br. J. Manag. 2010, 21, 511–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okta Tri, B.P. An Analysis of a Dominant Students’ Problem in Speaking at English Teacher Education Department Uin Sunan Ampel Surabaya. Ph.D. Thesis, UIN Sunan Ampel Surabaya, Surabaya, Indonesia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Tsui, A.S.; Egan, T.D.; O’Reilly III, C.A. Being different: Relational demography and organizational attachment. Adm. Sci. Q. 1992, 37, 549–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turker, D. Measuring corporate social responsibility: A scale development study. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 85, 411–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maignan, I.; Ferrell, O.C. Measuring corporate citizenship in two countries: The case of the United States and France. J. Bus. Ethics 2000, 23, 283–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochran, W.G. Sampling Techniques, 3rd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong, J.S.; Overton, T.S. Estimating nonresponse bias in mail surveys. J. Mark. Res. 1977, 14, 396–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harman, H.H. Modern Factor Analysis; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1976; ISBN 0226316521. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric Theory; McGraw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Kleinbaum, D.G.; Kupper, L.L.; Muller, K.E. Applied Regression Analysys and Other Nultivariable Methods. In Applied Regression Analysys and Other Nultivariable Methods; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 1988; p. 718. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. Partial least squares: The better approach to structural equation modeling? Long Range Plan. 2012, 45, 312–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Gabriel, M.; Patel, V. AMOS covariance-based structural equation modeling (CB-SEM): Guidelines on its application as a marketing research tool. Braz. J. Mark. 2014, 13, 44–55. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sinkovics, R.R. The use of partial least squares path modeling in international marketing. In New Challenges to International Marketing; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bradford, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Duarte, P.A.O.; Raposo, M.L.B. A PLS model to study brand preference: An application to the mobile phone market. In Handbook of Partial Least Squares; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 449–485. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Bookstein, F.L. Two structural equation models: LISREL and PLS applied to consumer exit-voice theory. J. Mark. Res. 1982, 19, 440–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holbert, R.L.; Stephenson, M.T. Structural Equation Modeling in the Communication Sciences, 1995–2000. Hum. Commun. Res. 2002, 28, 531–551. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler, P.M.; Bonett, D.G. Significance Tests and Goodness of Fit in the Analysis of Covariance Structures. Psychol. Bull. 1980, 88, 588–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jöreskog, K.G.; Sörbom, D. LISREL 8: Structural Equation Modeling with the SIMPLIS Command Language; Scientific Software International: Skokie, IL, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald, R.P.; Ho, M.-H.R. Principles and Practice in Reporting Structural Equation Analyses. Psychol. Methods 2002, 7, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. On the Evaluation of Structural Equation Models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, M.W.; Cudeck, R. Testing Structural Equation Models. In Alternative Ways of Assessing Model Fit; Bollen, K.A., Long, J.S., Eds.; Sage: New York, NY, USA, 1993; pp. 136–162. [Google Scholar]

- Farid, T.; Iqbal, S.; Ma, J.; Castro-González, S.; Khattak, A.; Khan, M.K. Employees’ perceptions of CSR, work engagement, and organizational citizenship behavior: The mediating effects of organizational justice. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Böckerman, P.; Bryson, A.; Ilmakunnas, P. Does high involvement management improve worker wellbeing? J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2012, 84, 660–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feisal, M.; Sandipan, S.; Katrina, S.; Hangjun, X. CSR and job satisfaction: Role of CSR importance to employee and procedural justice. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2021, 29, 518–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Hoegen, M.; Dugundji, J.; Wardle, B.L. Modeling and experimental verification of proof mass effects on vibration energy harvester performance. Smart Mater. Struct. 2010, 19, 045023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raub, S.; Blunschi, S. The power of meaningful work: How awareness of CSR initiatives fosters task significance and positive work outcomes in service employees. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2014, 55, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilham, R. The impact of organizational culture and leadership style on job satisfaction and employee performance. J. Adv. Manag. Sci. 2018, 6, 50–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. Motivation, leadership, and organization: Do American theories apply abroad? Organ. Dyn. 1980, 9, 42–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trompenaars, F.; Woolliams, P. A new framework for managing change across cultures. J. Chang. Manag. 2002, 3, 361–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- House, R.J.; Hanges, P.J.; Javidan, M.; Dorfman, P.W.; Gupta, V. (Eds.) Culture, Leadership, and Organizations: The Globe Study of 62 Societies; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Eskildsen, J.; Kristensen, K.; Antvor, H.G. The relationship between job satisfaction and national culture. TQM J. 2010, 22, 369–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Description | Classification | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 18–25 years | 34.8 |

| 26–30 years | 14.5 | |

| 31–35 years | 20.1 | |

| 36–40 years | 15.1 | |

| >40 years | 15.6 | |

| Gender | Male | 40.4 |

| Female | 59.6 | |

| Education | Bachelors | 55.5 |

| Masters | 29.4 | |

| Doctorate | 15.1 | |

| Experience | <2 years | 13.2 |

| 2–5 years | 26.3 | |

| 5–10 years | 20.5 | |

| 10–15 years | 15.8 | |

| >15 years | 24.2 | |

| Nationality | Saudi | 37.6 |

| Non-Saudi | 62.4 |

| Constructs | Item Loading | AVE | CR | α Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organizational Culture | ||||

| How trustworthy is my management? (OC1) | 0.843 | |||

| Is my organization’s learning and innovation culture satisfactory? (OC2) | 0.764 | 0.794 | 0.825 | 0.846 |

| I am satisfied with the available task opportunities in my organization to grow? (OC3) | 0.825 | |||

| I am satisfied with the collaboration (role) with whom I work? (OC4) | 0.788 | |||

| Corporate Social Responsibility | ||||

| I believe we have been successful at maximizing our profits and closely monitor employee’s productivity. (CSR1) | 0.768 | |||

| Our company encourage the diversity of our workforce and seeks to comply with all laws regulating hiring and employee benefits. (CSR2) | 0.757 | |||

| Our company’s internal policies prevent discrimination in employees’ compensation and promotion. (CSR3) | 0.705 | 0.607 | 0.839 | 0.815 |

| Fairness toward co-workers and business partners is an integral part of the employee evaluation process. (CSR4) | 0.897 | |||

| A confidential procedure is in place for employees to report any misconduct at work. (CSR5) | 0.927 | |||

| Our business supports employees who acquire additional education. (CSR6) | 0.746 | |||

| Job Satisfaction | ||||

| I am satisfied with the nature of the work I perform? (JS1) | 0.723 | |||

| I am satisfied with the person who supervises me at work (organizational superior)? (JS2) | 0.774 | |||

| I am satisfied with my relations with others in the organization with whom I work (co-workers or peers)? (JS3) | 0.736 | 0.675 | 0.824 | 0.869 |

| I am satisfied with the pay I receive for my job? (JS4) | 0.717 | |||

| I am satisfied with the opportunities which exist in this organization for career advancement (higher education, promotion)? (JS5) | 0.742 | |||

| From all perspectives, how satisfied are you with your current job situation? (JS6) | 0.817 |

| Constructs | OC | CSR | JS |

|---|---|---|---|

| OC | 0.795 | ||

| CSR | 0.678 | 0.845 | |

| JS | 0.751 | 0.725 | 0.868 |

| Fit Indices | Measurement Values of CFA | Measurement Values of Structural Model | Standard Value | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| χ2/df | 2.468 | 2.614 | <3 | [94] |

| IFI | 0.935 | 0.923 | >0.900 | [95] |

| NFI | 0.924 | 0.916 | >0.900 | [95] |

| CFI | 0.923 | 0.914 | >0.900 | [96] |

| GFI | 0.915 | 0.904 | >0.900 | [95] |

| AGFI | 0.924 | 0.918 | >0.900 | [93] |

| TLI | 0.934 | 0.927 | ≥0.900 | [97] |

| SRMR | 0.046 | 0.064 | <0.080 | [95] |

| RMSEA | 0.065 | 0.076 | <0.080 | [97,98] |

| Hypothesis | Unstandardized Beta | Std. Error | Standardized Beta Value | t Statistics | p Value | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1: OC → JS | 0.509 | 0.048 | 0.509 | 10.571 | <0.001 | Supported |

| H2: CSR → JS | 0.221 | 0.055 | 0.221 | 3.993 | <0.001 | Supported |

| H3: OC*CSR → JS | 0.077 | 0.026 | 0.141 | 2.976 | 0.003 | Supported |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Khan, S.; Alonazi, W.B.; Malik, A.; Zainol, N.R. Does Corporate Social Responsibility Moderate the Nexus of Organizational Culture and Job Satisfaction? Sustainability 2023, 15, 8810. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15118810

Khan S, Alonazi WB, Malik A, Zainol NR. Does Corporate Social Responsibility Moderate the Nexus of Organizational Culture and Job Satisfaction? Sustainability. 2023; 15(11):8810. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15118810

Chicago/Turabian StyleKhan, Sania, Wadi B. Alonazi, Azam Malik, and Noor Raihani Zainol. 2023. "Does Corporate Social Responsibility Moderate the Nexus of Organizational Culture and Job Satisfaction?" Sustainability 15, no. 11: 8810. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15118810

APA StyleKhan, S., Alonazi, W. B., Malik, A., & Zainol, N. R. (2023). Does Corporate Social Responsibility Moderate the Nexus of Organizational Culture and Job Satisfaction? Sustainability, 15(11), 8810. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15118810