Local Climate Adaptation and Governance: The Utility of Joint SECAP Plans for Networks of Small–Medium Italian Municipalities

Abstract

1. Introduction

- the nature of adaptation actions and validity of the shared approach in the process of constructing and implementing actions for adaptation;

- ways of managing the complexity of multiple levels and actors to pursue concrete actions on the ground for mitigating local vulnerabilities rather than becoming a source of conflict between actors and entities on different levels;

- concrete reasons for the usefulness of Joint SECAPs in small and medium municipalities with particular reference to defining and managing climate change adaptation strategies.

2. The Potential of Joint SECAPs and Their Implementation in Italy

- The fragmentation of skills among different sectors of the public administration and the absence of coordination between them [58].

- The sector-based approach of SECAPs and the lack of an integrated urban vision do not encourage their consideration as institutional tools on par with urban plans, regulations, etc. They are often simply considered as tools for planning and financing ordinary interventions in urban areas [44].

- Greater harmonisation of data and methods;

- Greater sharing of technical skills as well as the necessary personnel, not only for adherence and preparing the plan, but also for the expected monitoring stages;

- More adequate management of the issues of climate-change adaptation by developing more stringent guidelines on the means of stating and calculating emissions;

- Strengthening promotional activities through the use of mechanisms that encourage the presentation of Joint SECAPs.

3. Materials and Methods

- Joint SECAP Unione Tresinaro Secchia (presented by the Unione dei Comuni di Baiso, Casalgrande, Castellarano, Rubiera, Scandiano, and Viano (Province of Reggio Emilia, Emilia-Romagna Region). Total population: about 81,000; approved by the municipalities in 2021. https://www.comune.scandiano.re.it/servizi/ambiente/piano-di-azione-per-lenergia-sostenibile-e-il-clima-Secap/, accessed on 3 March 2023.

- Joint SECAP Terre Estensi (presented by the Associazione Intercomunale pursuant to Art. 8 Regional Law no. 11 of 26 April 2001), Participants: Municipalities of Ferrara, Voghiera, and Masi Torello. Total population: about 139,000, approved by the municipalities in 2019. https://www.pattodeisindaci.eu/about-it/la-comunit%C3%A0-del-patto/firmatari/piano-d-azione.html?scity_id=16127, accessed on 3 March 2023.

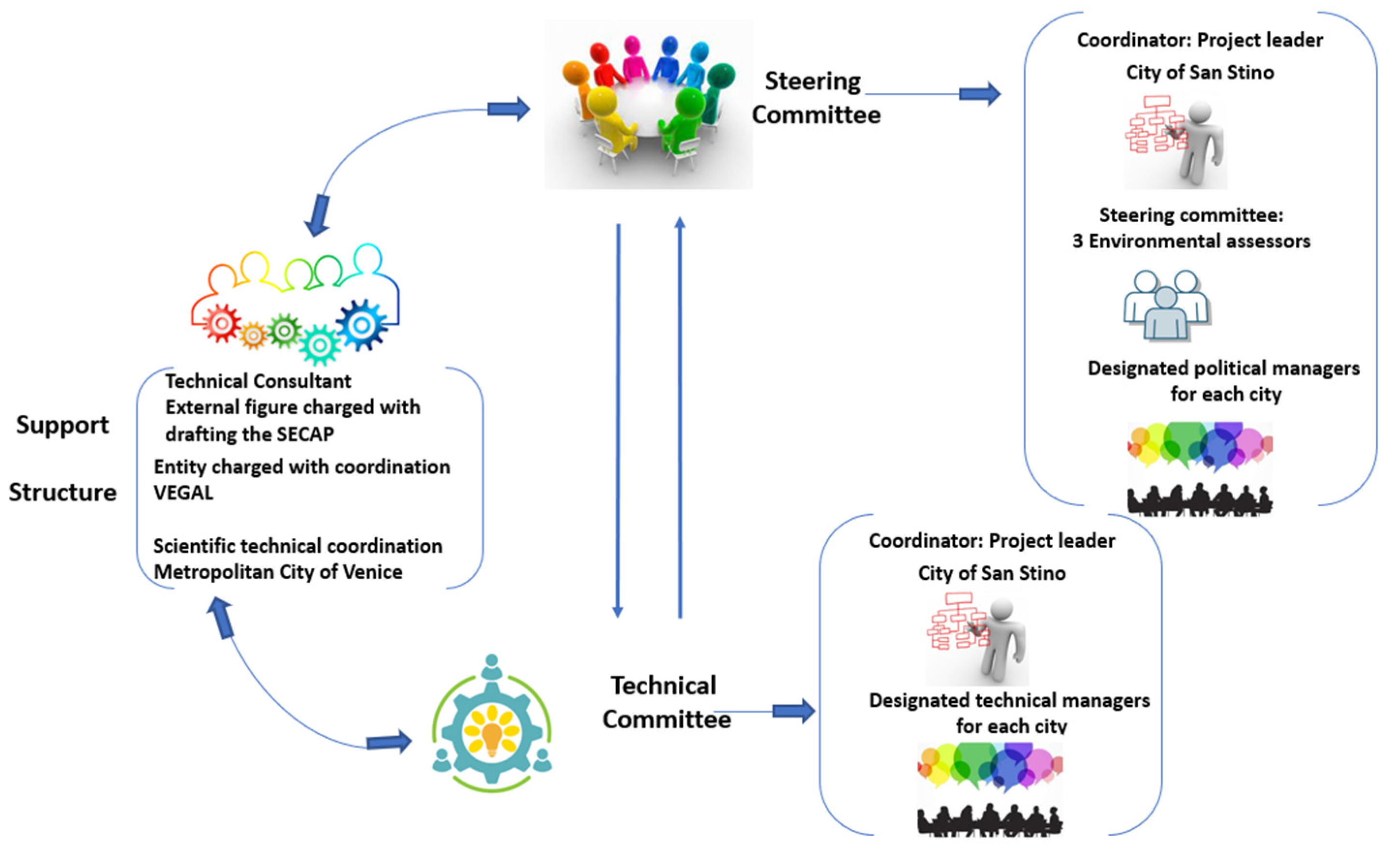

- Joint SECAP ‘Venezia Orientale Resiliente’ (presented by the Conferenza dei Sindaci del Veneto Orientale: Veneto Regional Law no. 16/93 and later modifications). Municipalities of: Annone Veneto, Caorle, Cavallino-Treporti, Ceggia, Cinto Caomaggiore, Concordia Sagittaria, Eraclea, Fossalta di Portogruaro, Gruaro, Jesolo, Meolo, Musile di Piave, Noventa di Piave, Portogruaro, Pramaggiore, Quarto d’Altino, San Michele al Tagliamento, San Donà di Piave, Santo Stino di Livenza, Teglio Veneto, Torre di Mosto, and Fossalta di Piave. Total population: 236,000; approved by the Conferenza dei Sindaci in 2020. This plan was developed under the European LIFE project ‘Veneto ADAPT’. https://www.vegal.net/catalogo/web/allegati/6051d98eab2d2_Presentazione_SECAP_light.pdf, accessed on 3 March 2023.

- Joint SECAP ‘Valle dell’Agno’ (presented by the aggregation of municipalities composed on Val d’Agno (Capofila), Recoaro Terme, Cornedo Vicentino, Brogliano, Castel Gomberto, and Trissino). Total population: about 63,000, agreement signed in 2016. http://www.comune.valdagno.vi.it/comune/progetti-e-attivita/Secap-valle-dellagno, accessed on 3 March 2023.

- Joint SECAP ‘Vesuviano’ (presented by the municipalities of Palma Campania, San Giovanni Vesuviano, Striano (NA). Total population: about 57,000. This is encompassed in the European network of Horizon 2020 PATH2LC projects. Public Authorities together with a holistic network approach on the way to low carbon municipalities. The city councils of the three municipalities approved the plan in 2021. In 2016, these municipalities activated the Municipal Office for Environmental Sustainability (Italian acronym UCSA) to facilitate and/or enhance management with regard to the environment, energy, and climate change adaptation. https://vcloud.ilger.com/cloud4/index.php/s/i5WxPPoKDpPWobs, accessed on 3 March 2023.

- Joint SECAP ‘Riviera delle Palme’ (presented by the municipalities of San Benedetto del Tronto, Cupra Marittima, Grottammare, and Monteprandone). This is included in the network of the Interreg Italia-Croazia ‘joint_SECAP’ project. Population: about 82,000. Joint SECAP currently being approved by the municipalities. https://it.readkong.com/page/la-partecipazione-del-territorio-nel-Secap-congiunto-della-5266974, accessed on 3 March 2023.

- how the adaptation strategy is constructed, with reference to awareness, risks, and impacts of climate change to address; common objectives and priorities among the different entities participating in the network; and type of adaptation actions selected;

- subjects and tools identified to facilitate the construction and implementation of the common adaptation actions;

- feasibility and synergy among the different adaptation actions and in relation to other public administration projects;

- role of participation among local actors, citizens, and public entities, and the role of communication to publicise the plans.

- a.

- The Joint SECAP Process

- b.

- Difficulties

- c.

- Collaborative Relationships

- d.

- Involvement of Local Populations and Actors

- alignment or misalignment in identifying the common priorities and objectives of the adaptation;

- the most common measures for implementing and monitoring the adaptation actions over time and managing their complexity, involving the multiple levels of governance and different actors;

- the most effective measures and tools to encourage acceptance of the adaptation actions by different stakeholders (technicians, entrepreneurs, public entities, and universities) and local communities.

4. Results

4.1. Analytical Investigation of the Plans in the Study

- Unione Tresinaro Secchia Joint SECAP

- (a)

- Adaptation Strategy

- (b)

- Feasibility and Synergy in Adaptation Actions

- (c)

- Participatory Process and Role of Communication/Dissemination

- Terre estensi Joint SECAP

- (a)

- Adaptation Strategy

- (b)

- Feasibility and Synergy in Adaptation Actions

- (c)

- Participatory Process and Role of Communication/Dissemination

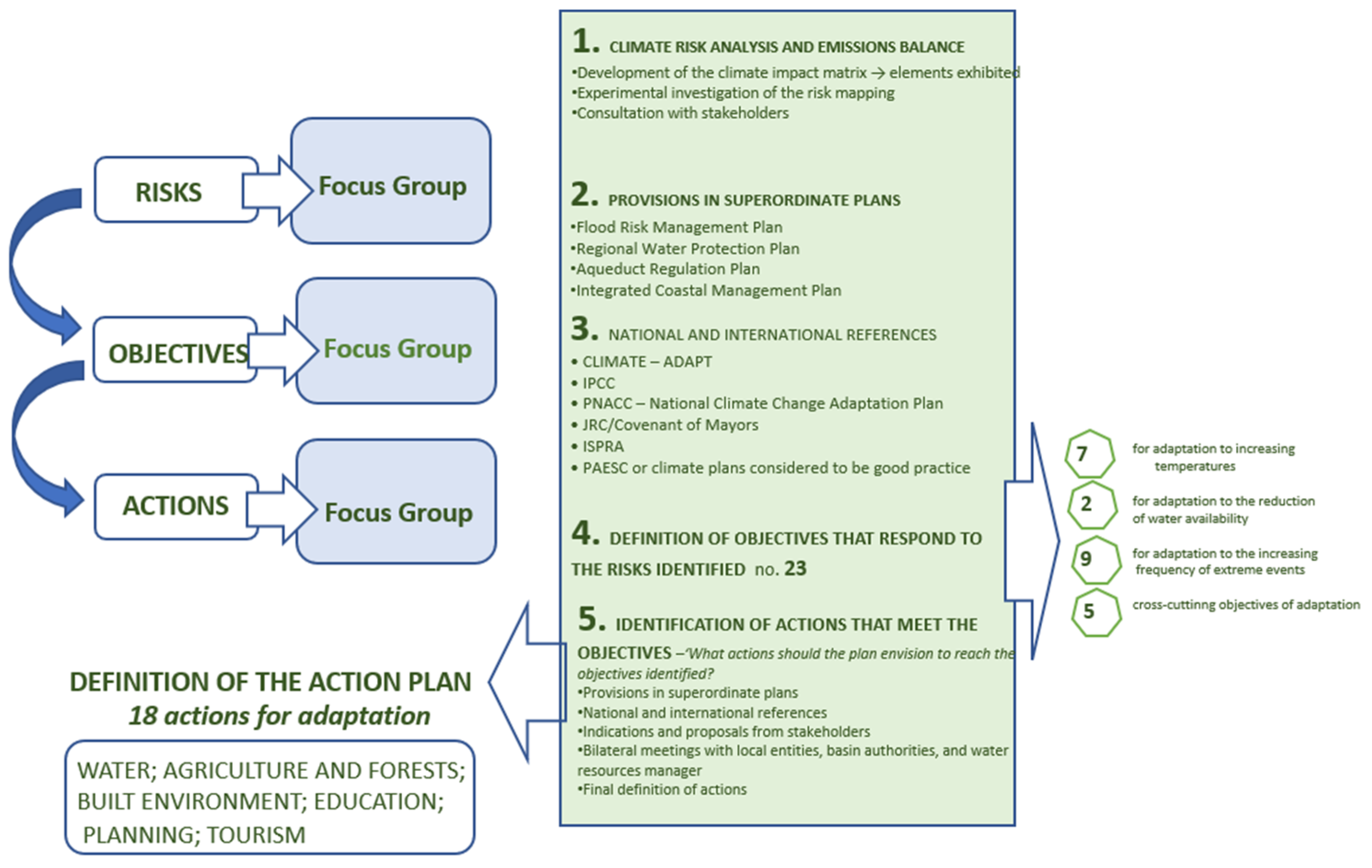

- Venezia Orientale Resiliente Joint Secap

- (a)

- Adaptation Strategy

- (b)

- Feasibility and Synergy in Adaptation Actions

- (c)

- Participatory Process and Role of Communication in Favouring the Success of the Plan

- Valle dell’Agno Joint SECAP

- (a)

- Adaptation Strategy

- (b)

- Feasibility and Synergy in Adaptation Actions

- (c)

- Participatory Process and Role of Communication in Favouring the Success of the Plan

- Vesuviano Joint SECAP

- (a)

- Adaptation Strategy

- (b)

- Feasibility and Synergy in Adaptation Actions

- (c)

- Participatory Process and Role of Communication in Favouring the Success of the Plan

- Riviera delle Palme Joint SECAP

- (a)

- Adaptation Strategy

- (b)

- Feasibility and Synergy in Adaptation Actions

- (c)

- Participatory Process and Role of Communication in Favouring the Success of the Plan

4.2. The Questionnaire for Joint SECAP Coordinators

4.3. Comparative Analysis of the Joint SECAPs

- a.

- Definition of Priorities and Common Adaptation Objectives

- b.

- Implementing Adaptation Actions and Monitoring their Performance over Time

- c.

- Capacity of the Plans to Manage Complexity

- d.

- Construction of Measures to Encourage the Acceptance and Sharing of Adaptation Actions

5. Conclusions

- Ensure policy consistency. Working both vertically between levels of government and horizontally between different actors on a given governance level to assess potential contradictions and synergy to minimize contradictions and exploit and expand interactions.

- Guarantee participatory governance and strategic planning on the relevant scale. Favouring reflection and understanding on how climate change and the climate protection policy will affect local communities and territorial development, helping to define a way to integrate climate protection and resilience in urban development planning.

- Guarantee citizen and stakeholder involvement throughout the adaptation design process.

- Address monitoring, reporting, and evaluation: selecting criteria to assess adaptation policies to validate the quality of performance achieved and possibly to make changes within an ongoing process of improvement and verification.

- Overcome the lack of personnel and skills in small–medium administrations, implementing structures or either internal or external figures in the public administration to coordinate activities to build knowledge, define actions for the plan, and share possible proposals for the future among the different institutional actors and local stakeholders.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Baker, I.; Peterson, A.; Brown, G.; McAlpine, C. Local government response to the impacts of climate change: An evaluation of local climate adaptation plans. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2012, 107, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bebbington, J.; Unerman, J.; O’Dwyer, B. Sustainability Accounting and Accountability; Taylor and Francis: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoppe, T.; van den Berg, M.M.; Coenen, F.H. Reflections on the Uptake of Climate Change Policies by Local Governments: Facing the Challenges of Mitigation and Adaptation. Energy Sustain. Soc. 2014, 4, 8. Available online: http://www.energsustainsoc.com/content/4/1/8 (accessed on 23 May 2023). [CrossRef]

- Amundsen, H.; Hovelsrud, G.K.; Aall, C.; Karlsson, M.; Westskog, H. Local governments as drivers for societal transformation: Towards the 1.5 °C ambition. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2018, 31, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguiar, F.C.; Bentz, J.; Silva, J.M.N.; Fonseca, A.L.; Swart, R.; Santos, F.D.; Penha-Lopes, G. Adaptation to climate change at local level in Europe: An overview. Environ. Sci. Policy 2018, 86, 38–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, T.T.T.; Oßenbrügge, J. Urban energy transitions and climate change; actions, relations and local dependences in Germany. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2020, 69, 101728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouldson, A.P.; Colenbrander, S.; Sudmant, A.; Godfrey, N.; Millward-Hopkins, J.; Fang, W.; Zhao, X. Accelerating Low-Carbon Development in the Worlds Cities. New Clim. Econ. 2015. Available online: https://www.newclimateeconomy.report (accessed on 26 March 2022).

- Van Staden, M.; Musco, F. (Eds.) Local Governments and Climate Change—Sustainable Energy Planning and Implementation in Small and Medium Sized Communities, 1st ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2010; Volume 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryngemark, E.; Söderholm, P.; Thörn, M. The adoption of green public procurement practices: Analytical challenges and empirical illustration on Swedish municipalities. Ecol. Econ. 2023, 204, 107655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kordos, V.; Golubovic, V.; Zunac, A.G. Green Public Procurement, Economic and Social Development: Book of Proceedings—83 rd International Scientific Conference on Economic and Social Development—“Green Marketing”; ZBW—Leibniz-Informationszentrum Wirtschaft/Leibniz Information Centre for Economics: Kiel, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson, D. Preparing for Climate Change—An Implementation Guide for Local Governments in British Columbia. 2012. Available online: https://www.wcel.org/publication/preparing-climate-change-implementation-guide-local-governments-british-columbia (accessed on 16 March 2022).

- European Commission. The European Green Deal. 2019. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/resource.html?uri=cellar:b828d165-1c22-11ea-8c1f-01aa75ed71a1.0002.02/DOC_1&format=PDF (accessed on 23 May 2023).

- European Commission. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. Forging a Climate-Resilient Europe—The New EU Strategy on Adaptation to Climate Change. 2021. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=COM:2021:82:FIN (accessed on 23 May 2023).

- Official Journal of the European Union. Regulation (EU) 2021/1119 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 30 June 2021 Establishing the Framework for Achieving Climate Neutrality and Amending Regulations (EC) No 401/2009 and (EU) 2018/1999 (‘European Climate Law’). 2021. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/homepage.html (accessed on 23 May 2023).

- Woodruff, S.C.; Meerow, S.; Stults, M.; Wilkins, C. Adaptation to Resilience Planning: Alternative Pathways to Prepare for Climate Change. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2018, 42, 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNFCCC. What Do Adaptation to Climate Change and Climate Resilience Mean? 2022. Available online: https://unfccc.int/topics/adaptation-and-resilience/the-big-picture/what-do-adaptation-toclimate-change-and-climate-resilience-mean (accessed on 23 May 2023).

- Thoidou, E. Spatial Planning and Climate Adaptation: Challenges of Land Protection in a Peri-Urban Area of the Mediterranean City of Thessaloniki. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, S.C.; Boykoff, M.T. Successful Adaptation to Climate Change Linking Science and Policy in a Rapidly Changing World; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Rivas, S.; Urraca, R.; Bertoldi, P.; Thiel, C. Towards the EU Green Deal: Local key factors to achieve ambitious 2030 climate targets. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 320, 128878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filho, W.L.; Shiel, C.; Paço, A.; Mifsud, M.; Ávila, L.V.; Brandli, L.L.; Molthan-Hill, P.; Pace, P.; Azeiteiro, U.M.; Vargas, V.R.; et al. Sustainable Development Goals and sustainability teaching at universities: Falling behind or getting ahead of the pack? J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 232, 285–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmen, E.; Fazey, I.; Ross, H.; Bedinger, M.; Smith, F.M.; Prager, K.; McClymont, K.; Morrison, D. Building community resilience in a context of climate change: The role of social capital. AMBIO 2022, 51, 1371–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fazey, I.; Carmen, E.; Ross, H.; Rao-Williams, J.; Hodgson, A.; Searle, B.A.; AlWaer, H.; Kenter, J.O.; Knox, K.; Butler, J.R.A.; et al. Social dynamics of community resilience building in the face of climate change: The case of three Scottish communities. Sustain. Sci. 2021, 16, 1731–1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EEA. EEA Report “Urban Adaptation in Europe: How Cities and Towns Respond to Climate Change”. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/358264183_Urban_adaptation_in_Europe_how_cities_and_towns_respond_to_climate_change (accessed on 23 May 2023).

- Reckien, D.; Flacke, J.; Dawson, R.J.; Heidrich, O.; Olazabal, M.; Foley, A.; Hamann, J.J.-P.; Orru, H.; Salvia, M.; De Gregorio Hurtado, S.; et al. Climate change response in Europe: What’s the reality? Analysis of adaptation and mitigation plans from 200 urban areas in 11 countries. Clim. Chang. 2014, 122, 331–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira, J.A.P.; Doll, C.N.H.; Kurniawan, T.A.; Geng, Y.; Kapshe, M.; Huisingh, D. Promoting win–win situations in climate change mitigation, local environmental quality and development in Asian cities through co-benefits. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 58, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reckien, D.; Salvia, M.; Heidrich, O.; Church, J.M.; Pietrapertosa, F.; De Gregorio-Hurtado, S.; D’Alonzo, V.; Foley, A.; Simoes, S.G.; Lorencová, E.K.; et al. How are cities planning to respond to climate change? Assessment of local climate plans from 885 cities in the EU-28. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 191, 207–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araos, M.; Berrang-Ford, L.; Ford, J.D.; Austin, S.E.; Biesbroek, R.; Lesnikowski, A. Climate change adaptation planning in large cities: A systematic global assessment. Environ. Sci. Policy 2016, 66, 375–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupuis, J.; Biesbroek, R. Comparing apples and oranges: The dependent variable problem in comparing and evaluating climate change adaptation policies. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2013, 23, 1476–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bausch, T.; Koziol, K. New Policy Approaches for Increasing Response to Climate Change in Small Rural Municipalities. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Häußler, S.; Haupt, W. Climate change adaptation networks for small and medium-sized cities. SN Soc. Sci. 2021, 1, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, A.; Kern, K.; Haupt, W.; Eckersley, P.; Thieken, A.H. Ranking local climate policy: Assessing the mitigation and adaptation activities of 104 German cities. Clim. Chang. 2021, 167, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitton, J.M.; Addo, K.A.; Jayson-Quashigah, P.-N.; Nagy, G.J.; Gutiérrez, O.; Panario, D.; Carro, I.; Seijo, L.; Segura, C.; Verocai, J.E.; et al. Challenges to climate change adaptation in coastal small towns: Examples from Ghana, Uruguay, Finland, Denmark, and Alaska. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2021, 212, 105787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covenant of Mayors. Flashback: The Origins of the Covenant of Mayors. Available online: https://www.covenantofmayors.eu/about/covenant-initiative/origins-and-development.html (accessed on 1 April 2022).

- Bertoldi, P.; Rivas Calvete, S.; Kona, A.; Hernandez Gonzalez, Y.; Marinho Ferreira Barbosa, P.; Palermo, V.; Baldi, M.; Lo Vullo EMuntean, M. Covenant of Mayors: 2019 Assessment; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2020; ISBN 978-92-76-10721-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basso, M.; Tonin, S. The implementation of the Covenant of Mayors initiative in European cities: A policy perspective. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 78, 103596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melica, G.; Treville, A.; Franco De Los Rios, C.; Baldi, M.; Monforti-Ferrario, F.; Palermo, V.; Ulpiani, G.; Ortega Hortelano, A.; Lo Vullo, E.; Marinho Ferreira Barbosa PBertoldi, P. Covenant of Mayors: 2021 Assessment; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Popering-Verkerk, J.; Molenveld, A.; Duijn, M.; van Leeuwen, C.; van Buuren, A. A Framework for Governance Capacity: A Broad Perspective on Steering Efforts in Society. Adm. Soc. 2022, 54, 1767–1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauge, L.; Hanssen, G.S.; Flyen, C. Multilevel networks for climate change adaptation—What works? Int. J. Clim. Chang. Strat. Manag. 2019, 11, 215–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landauer, M.; Juhola, S.; Klein, J. The role of scale in integrating climate change adaptation and mitigation in cities. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2019, 62, 741–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, K. Flows in formation: The global-urban networks of climate change adaptation. Urban Stud. 2020, 57, 2222–2240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijerink, S.; Stiller, S. What Kind of Leadership Do We Need for Climate Adaptation? A Framework for Analyzing Leadership Objectives, Functions, and Tasks in Climate Change Adaptation. Environ. Plan. C Gov. Policy 2013, 31, 240–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, J.C.; Knierim, A.; Knuth, U. Policy-induced innovations networks on climate change adaptation—An ex-post analysis of collaboration success and its influencing factors. Environ. Sci. Policy 2016, 56, 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granberg, M.; Elander, I. Local Governance and Climate Change: Reflections on the Swedish Experience. Local Environ. 2007, 12, 537–548. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/235734847_Local_Governance_and_Climate_Change_Reflections_on_the_Swedish_Experience (accessed on 23 May 2023). [CrossRef]

- Scorza, F.; Santopietro, L. A systemic perspective for the Sustainable Energy and Climate Action Plan (SECAP). Eur. Plan. Stud. 2021, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laukkonen, J.; Blanco, P.K.; Lenhart, J.; Keiner, M.; Cavric, B.; Kinuthia-Njenga, C. Combining climate change adaptation and mitigation measures at the local level. Habitat Int. 2009, 33, 287–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertoldi, P. (Ed.) Guidebook ‘How to Develop a Sustainable Energy and Climate Action Plan (SECAP)—PART 3—Policies, Key Actions, Good Practices for Mitigation and Adaptation to Climate Change and Financing SECAP(s)’; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teebken, J.A.; Mitchell, N.; Jacob, K. Adaptation Platforms—A Way Forward for Adaptation Governance in Small Cities? Lessons Learned from Two Cities in Germany. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4295483 (accessed on 23 May 2023).

- Santopietro, L.; Scorza, F. The Italian Experience of the Covenant of Mayors: A Territorial Evaluation. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covenant of Mayors. Quick Reference Guide. Joint Sustainable Energy & Climate Action Plan. 2017. Available online: https://www.covenantofmayors.eu/support/reporting.html (accessed on 23 May 2023).

- Torelli, G. Il Contrasto ai Cambiamenti Climatici nel Governo del Territorio. 2020. Available online: https://www.federalismi.it/nv14/articolo-documento.cfm?Artid=40908 (accessed on 23 May 2023).

- Koch, I.C.; Vogel, C.; Patel, Z. Institutional dynamics and climate change adaptation in South Africa. Mitig. Adapt. Strat. Glob. Chang. 2007, 12, 1323–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, A.; Sheppard, S.; Burch, S.; Flanders, D.; Wiek, A.; Carmichael, J.; Robinson, J.; Cohen, S. Making local futures tangible—Synthesizing, downscaling, and visualizing climate change scenarios for participatory capacity building. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2009, 19, 447–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardsley, D.K.; Sweeney, S.M. Guiding climate change adaptation within vulnerable natural resource management systems. Environ. Manag. 2010, 45, 1127–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corfee-Morlot, J.; Cochran, I.; Hallegatte, S.; Teasdale, P.-J. Multilevel risk governance and urban adaptation policy. Clim. Chang. 2011, 104, 169–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biesbroek, G.R.; Klostermann, J.E.M.; Termeer, C.J.A.M.; Kabat, P. On the nature of barriers to climate change adaptation. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2013, 13, 1119–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Göpfert, C.; Wamsler, C.; Lang, W. Enhancing structures for joint climate change mitigation and adaptation action in city administrations—Empirical insights and practical implications. City Environ. Interact. 2020, 8, 100052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melica, G. Multilevel governance of sustainable energy policies: The role of regions and provinces to support the participation of small local authorities in the covenant of mayors. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2018, 39, 729–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uyl, R.M.D.; Russel, D.J. Climate adaptation in fragmented governance settings: The consequences of reform in public administration. Environ. Politics 2022, 27, 341–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chassein, E.; Frank, V.S. Path2LC. D4.9 SE(C)APs: From Municipal Planning to Concrete Action Barriers, Success Factors and Decision Processes. 2021. Available online: https://www.path2lc.eu/the-project/ (accessed on 23 May 2023).

- Ispra. Stato di Attuazione del Patto dei Sindaci in Italia, Rapporti 316/2020. 2020. Available online: https://www.isprambiente.gov.it/it/pubblicazioni/rapporti/stato-di-attuazione-del-patto-dei-sindaci-in-italia (accessed on 23 May 2023).

- Cullingworth, J.B.; Caves, R. Planning in the USA, 3rd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Betsill, M.; Bulkeley, H. Cities and the Multilevel Governance of Global Climate Change. Glob. Gov. 2006, 12, 141–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corfee-Morlot, J.; Lamia Kamal-Chaoui Donovan, M.G.; Cochran, I.; Alexis, R.; Teasdale, J.P. Cities, Climate Change and Multilevel Governance; OECD Environmental Working Papers N° 14; OECD: Paris, France, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson, M.; Zamparutti, T.; Petersen, J.E.; Nykvist, B.; Rudberg, P.; McGuinn, J. Understanding Policy Coherence: Analytical Framework and Examples of Sector-Environment Policy Interactions in the EU. Environ. Policy Gov. 2012, 22, 395–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dale, A.; Burch, S.; Robinson, J.; Strashok, C. Multilevel Governance of Sustainability Transitions in Canada: Policy Alignment, Innovation, and Evaluation. In Climate Change in Cities Innovations in Multi-Level Governance; Hughes, S., Chu, E., Mason, S., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Dietz, T.; Ostrom, E.; Stern, P.C. The Struggle to Govern the Commons. Science 2003, 232, 1907–1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kern, K.; Bulkeley, H. Cities, Europeanization and Multi-level Governance: Governing Climate Change through Transnational Municipal Networks. JCMS 2009, 47, 309–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrapertosa, F.; Salvia, M.; Hurtado, S.D.G.; Geneletti, D.; D’Alonzo, V.; Reckien, D. Multi-level climate change planning: An analysis of the Italian case. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 289, 112469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jänicke, M.; Quitzow, R. Multi-level Reinforcement in European Climate and Energy Governance: Mobilizing economic interests at the sub-national levels. Environ. Policy Gov. 2017, 27, 122–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christoforidis, G.C.; Chatzisavvas, K.C.; Lazarou, S.; Parisses, C. Covenant of Mayors initiative—Public perception is-sues and barriers in Greece. Energy Policy 2013, 60, 643–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

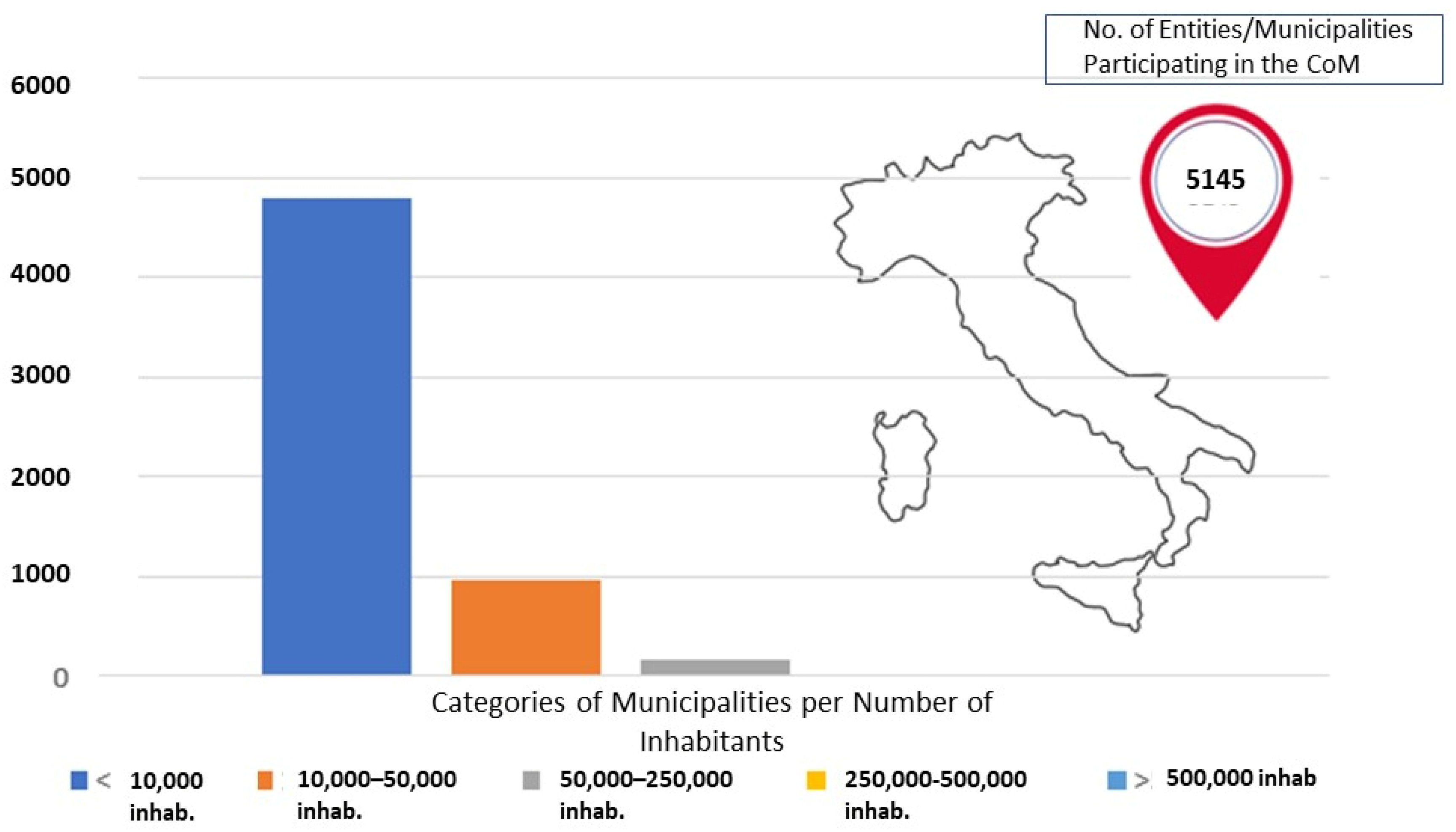

| Italian Signatories of the Covenant of Mayors | Signatories Who Have Submitted an Action Plan | Signatories That Have Monitored the Action Plan | Signatories That Have Made Commitments with Respect to Adaptation | TOT |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <10,000 residents | 2497 (70%) | 703 (20%) | 354 (10%) | 3554 |

| 10,000–50,000 | 686 (60%) | 279 (24%) | 195 (16%) | 1160 |

| 50,000–250,000 | 115 (52%) | 57 (26%) | 47 (22%) | 219 |

| 250,000–500,000 | 9 (50%) | 4 (22%) | 5 (28%) | 18 |

| >500,000 | 5 (38%) | 4 (31%) | 4 (31%) | 13 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

D’Onofrio, R.; Camaioni, C.; Mugnoz, S. Local Climate Adaptation and Governance: The Utility of Joint SECAP Plans for Networks of Small–Medium Italian Municipalities. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8738. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15118738

D’Onofrio R, Camaioni C, Mugnoz S. Local Climate Adaptation and Governance: The Utility of Joint SECAP Plans for Networks of Small–Medium Italian Municipalities. Sustainability. 2023; 15(11):8738. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15118738

Chicago/Turabian StyleD’Onofrio, Rosalba, Chiara Camaioni, and Stefano Mugnoz. 2023. "Local Climate Adaptation and Governance: The Utility of Joint SECAP Plans for Networks of Small–Medium Italian Municipalities" Sustainability 15, no. 11: 8738. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15118738

APA StyleD’Onofrio, R., Camaioni, C., & Mugnoz, S. (2023). Local Climate Adaptation and Governance: The Utility of Joint SECAP Plans for Networks of Small–Medium Italian Municipalities. Sustainability, 15(11), 8738. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15118738