Decoding the Dilemma of Consumer Food Over-Ordering in Restaurants: An Augmented Theory of Planned Behavior Model Investigation

Abstract

1. Introduction

| Author | Country Focus | Study Focus | Underpinning Theory |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hu et al. [21] | Japan | Pro-environmental behavior (waste Separation) | TPB |

| Zhang et al. [22] | China | Pro-environmental behavior (waste Separation) | TPB |

| Coşkun and Yetkin Özbük [23] | Turkey | Pro-environmental behavior (food waste) | TPB |

| Heidari et al. [24] | Iran | Pro-environmental behavior (waste Separation) | TPB |

| Li et al. [25] | China | Pro-environmental behavior (waste reduction) | TPB |

| Soomro et al. [26] | Saudi Arabia | Pro-environmental behavior (waste recycling) | TPB |

| Graham-Rowe et al. [27] | United Kingdom | Pro-environmental behavior (food waste reduction) | TPB |

| Mak et al. [28] | Hong Kong | Pro-environmental behavior (food waste recycling) | TPB |

| Author | Country Focus | Study Focus | Underpinning Theory |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wang et al. [29] | China | Pro-environmental behavior (waste Separation) | NAM |

| Kim et al. [30] | South Korea | Pro-environmental behavior (food waste reduction) | NAM |

| Wang et al. [31] | China | Pro-environmental behavior (food waste) | NAM |

| Nketiah et al. [32] | China | Pro-environmental behavior (waste recycling) | NAM |

| Song et al. [33] | China | Pro-environmental behavior (reusable express packaging) | NAM |

| Han [34] | USA | Pro-environmental behavior (responsible tourism) | NAM |

| Savari et al. [35] | IRAN | Pro-environmental behavior (Water conservation) | NAM |

| Zhang et al. [36] | China | Pro-environmental behavior (energy saving) | NAM |

2. Theoretical Background and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Theory of Planned Behavior

2.2. Norm Activation Model

2.3. The Moderation Effect of the Concept of “Mianzi”

3. Method

3.1. Measures

3.2. Study Design and Data Collection

3.3. Data Analysis Techniques

4. Result Analysis

4.1. Common Method Variance (CMV)

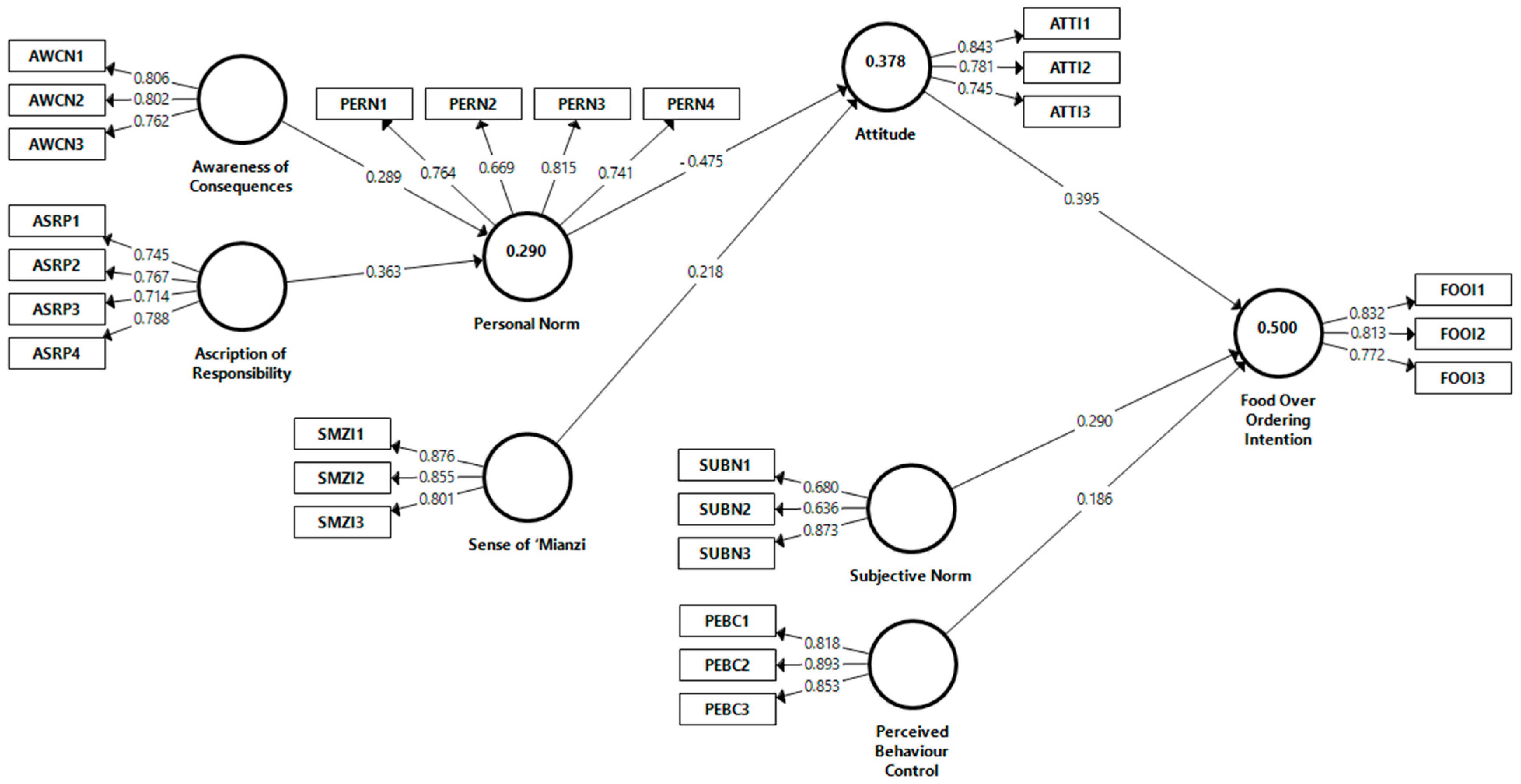

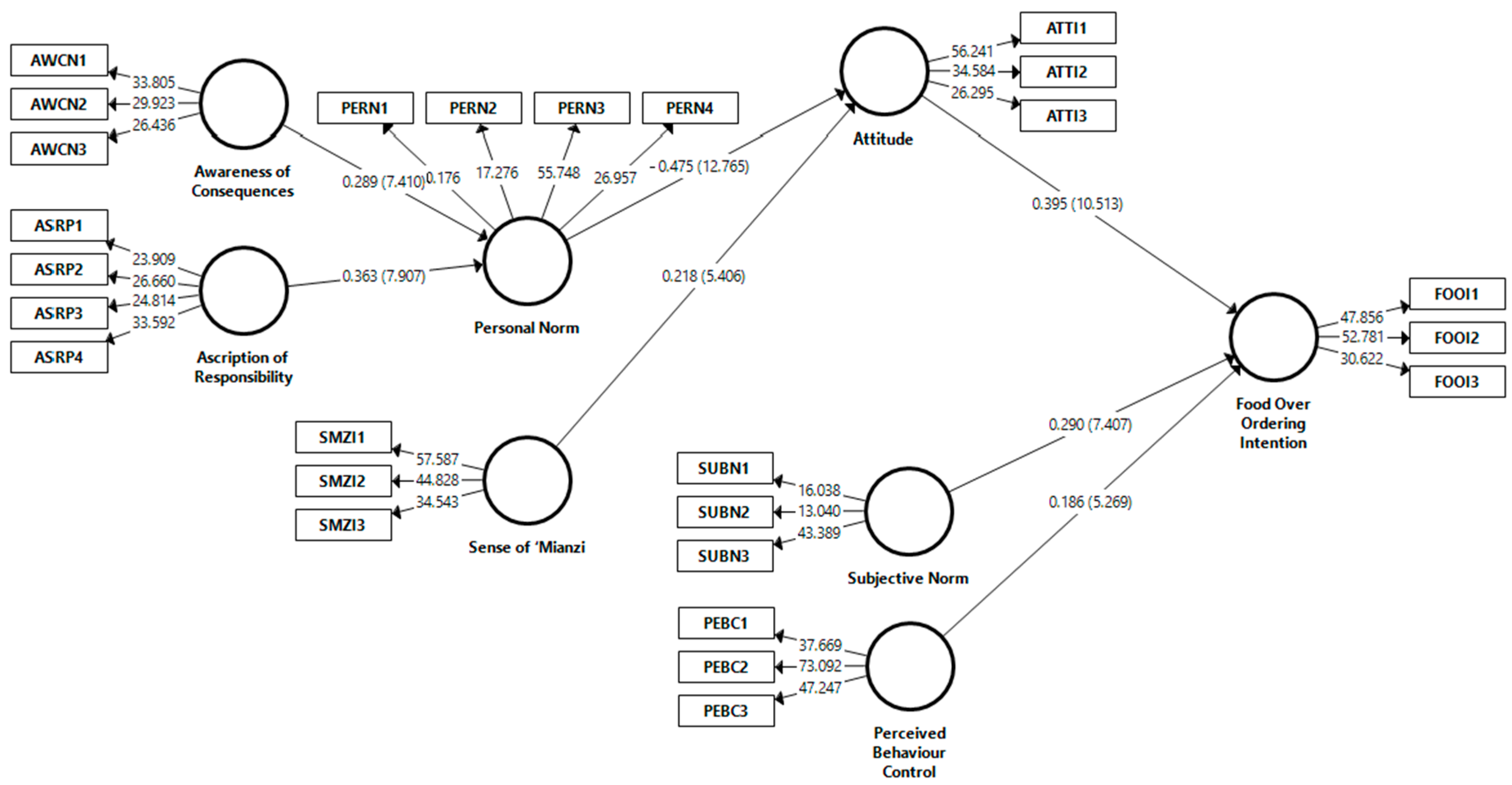

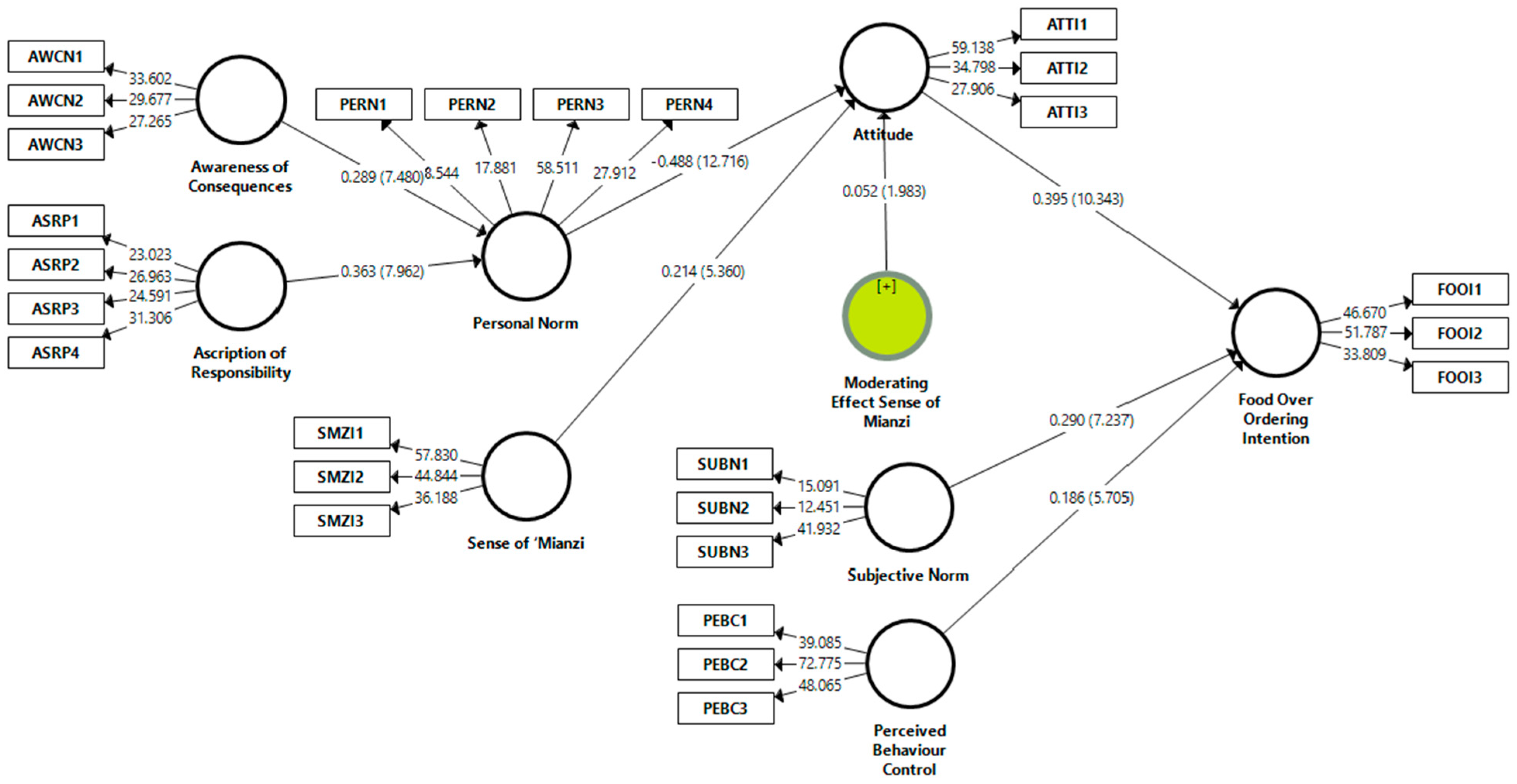

4.2. Measurement Model Assessment

Structural Model Analysis

5. Discussion and Implications

5.1. Theoretical Contribution

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Filimonau, V.; De Coteau, D.A. Food waste management in hospitality operations: A critical review. Tour. Manag. 2019, 71, 234–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de los Mozos, E.A.; Badurdeen, F.; Dossou, P.E. Sustainable Consumption by Reducing Food Waste: A Review of the Current State and Directions for Future Research. Procedia Manuf. 2020, 51, 1791–1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Food Loss and Waste Must Be Reduced for Greater Food Security and Environmental Sustainability. 2020. Available online: https://www.fao.org/news/story/en/item/1310271/icode/ (accessed on 26 April 2023).

- FAO. Tackling Food Loss and Waste: A Triple Win Opportunity; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Sethi, G.; Bedregal, L.P.A.; Cassou, E.; Constantino, L.; Hou, X.; Jain, S.; Messent, F.; Morales, X.Z.; Mostafa, I.; Pascual, J.C.G.; et al. Addressing Food Loss and Waste: A Global Problem with Local Solutions; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- UNEP. UNEP Food Waste Index Report 2021; UNEP—UN Environment Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Amicarelli, V.; Aluculesei, A.C.; Lagioia, G.; Pamfilie, R.; Bux, C. How to manage and minimize food waste in the hotel industry: An exploratory research. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2022, 16, 152–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Ju, X.; Bai, L.; Gong, S. Consumer’s over-ordering behavior at restaurant: Understanding the important roles of interventions from waiter and ordering habits. Appetite 2021, 160, 105092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vizzoto, F.; Testa, F.; Iraldo, F. Strategies to reduce food waste in the foodservices sector: A systematic review. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 95, 102933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, O. Food Waste in China: Whose Fault Is It? Available online: https://news.cgtn.com/news/3d3d514e7841544f7a457a6333566d54/share_p.html (accessed on 2 January 2023).

- Papargyropoulou, E.; Wright, N.; Lozano, R.; Steinberger, J.; Padfield, R.; Ujang, Z. Conceptual framework for the study of food waste generation and prevention in the hospitality sector. Waste Manag. 2016, 49, 326–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Yang, Y.; Wang, G. The Clean Your Plate Campaign: Resisting Table Food Waste in an Unstable World. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clean Plate Campaign. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Clean_Plate_campaign (accessed on 2 January 2023).

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H. Normative influences on altruism. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1977, 10, 221–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y.H.; Im, J.; Jung, S.E.; Severt, K. The theory of planned behavior and the norm activation model approach to consumer behavior regarding organic menus. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 69, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, R.; Safa, L.; Damalas, C.A.; Ganjkhanloo, M.M. Drivers of farmers’ intention to use integrated pest management: Integrating theory of planned behavior and norm activation model. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 236, 328–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Wang, J. Food waste of Chinese cruise passengers. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 1825–1840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S. Analysis on food consumption and waste of China. Food Nutr. China 2005, 11, 6–10. [Google Scholar]

- Talwar, S.; Kaur, P.; Ahmed, U.; Bilgihan, A.; Dhir, A. The dark side of convenience: How to reduce food waste induced by food delivery apps. Br. Food J. 2023, 125, 205–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Tang, K.; Qian, X.; Sun, F.; Zhou, W. Behavioral change in waste separation at source in an international community: An application of the theory of planned behavior. Waste Manag. 2021, 135, 397–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.; Huang, G.; Yin, X.; Gong, Q. Residents’ Waste Separation Behaviors at the Source: Using SEM with the Theory of Planned Behavior in Guangzhou, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 9475–9491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coşkun, A.; Yetkin Özbük, R.M. What influences consumer food waste behavior in restaurants? An application of the extended theory of planned behavior. Waste Manag. 2020, 117, 170–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heidari, A.; Kolahi, M.; Behravesh, N.; Ghorbanyon, M.; Ehsanmansh, F.; Hashemolhosini, N.; Zanganeh, F. Youth and sustainable waste management: A SEM approach and extended theory of planned behavior. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 2018, 20, 2041–2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zuo, J.; Cai, H.; Zillante, G. Construction waste reduction behavior of contractor employees: An extended theory of planned behavior model approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 172, 1399–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soomro, Y.A.; Hameed, I.; Bhutto, M.Y.; Waris, I.; Baeshen, Y.; Batati, B. Al What Influences Consumers to Recycle Solid Waste? An Application of the Extended Theory of Planned Behavior in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Sustainability 2022, 14, 998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham-Rowe, E.; Jessop, D.C.; Sparks, P. Predicting household food waste reduction using an extended theory of planned behaviour. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2015, 101, 194–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, T.M.W.; Yu, I.K.M.; Tsang, D.C.W.; Hsu, S.C.; Poon, C.S. Promoting food waste recycling in the commercial and industrial sector by extending the Theory of Planned Behaviour: A Hong Kong case study. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 204, 1034–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, J.; Zhao, S.; Yang, S. Information publicity and resident’s waste separation behavior: An empirical study based on the norm activation model. Waste Manag. 2019, 87, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, W.; Che, C.; Jeong, C. Food Waste Reduction from Customers’ Plates: Applying the Norm Activation Model in South Korean Context. Land 2022, 11, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, M.; Li, S.; Chen, K. Understanding Consumers’ Food Waste Reduction Behavior—A Study Based on Extended Norm Activation Theory. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nketiah, E.; Song, H.; Cai, X.; Adjei, M.; Obuobi, B.; Adu-Gyamfi, G.; Cudjoe, D. Predicting citizens’ recycling intention: Incorporating natural bonding and place identity into the extended norm activation model. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 377, 134425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Cai, L.; Yuen, K.F.; Wang, X. Exploring consumers’ usage intention of reusable express packaging: An extended norm activation model. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 72, 103265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H. The norm activation model and theory-broadening: Individuals’ decision-making on environmentally-responsible convention attendance. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 40, 462–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savari, M.; Abdeshahi, A.; Gharechaee, H.; Nasrollahian, O. Explaining farmers’ response to water crisis through theory of the norm activation model: Evidence from Iran. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2021, 60, 102284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, G. Antecedents of employee electricity saving behavior in organizations: An empirical study based on norm activation model. Energy Policy 2013, 62, 1120–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M. Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behaviour; Prentice-Hall, Inc.: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, S.; Javed, H.M.U.; Danish, M. Adoption of green IT in Pakistan: A comparison of three competing models through model selection criteria using PLS-SEM. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 36174–36192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, S.; Usama Javed, H.M.; Ali, W.; Zahid, H. Decoding men’s behavioral responses toward green cosmetics: An investigation based on the belief decomposition approach. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2022, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steg, L.; Bolderdijk, J.W.; Keizer, K.; Perlaviciute, G. An Integrated Framework for Encouraging Pro-environmental Behaviour: The role of values, situational factors and goals. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 38, 104–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Groot, J.; Steg, L. Morality and Prosocial Behavior: The Role of Awareness, Responsibility, and Norms in the Norm Activation Model. J. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 149, 425–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, W.; Razzaque, M.A.; Keng, K.A. Chinese cultural values and gift-giving behavior. J. Consum. Mark. 2007, 24, 214–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.J.; Su, C. How face influences consumption A comparative study of American and Chinese consumers. Int. J. Mark. Res. 2007, 49, 237–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Kunasekaran, P.; Zhao, Y. Understanding over-ordering behaviour in social dining: Integrating mass media exposure and sense of ‘Mianzi’ into the Norm Activation Model. Serv. Ind. J. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, D.R.; Rao, T.R. Analysis of Customer Satisfaction Data: A comprehensive Guide to Multivariate Statistical Analysis in Customer Satisfaction, Loyalty, and Service Quality Research; Asq Press: Milwaukee, WI, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bearden, W.; Netemeyer, R. Handbook of Marketing Scales: Multi-Item Measures for Marketing and Consumer Behavior Research; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousands Oaks, CA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Foddy, W. Constructing Questions for Interviews and Questionnaires: Theory and Practice in Social Research; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Ajina, A.S.; Javed, H.M.U.; Ali, S.; Zamil, A.M.A. Are men from mars, women from venus? Examining gender differences of consumers towards mobile-wallet adoption during pandemic. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Sarstedt, M.; Hopkins, L.; Kuppelwieser, V.G. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM)An emerging tool in business research. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2014, 26, 106–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nulty, D.D. The adequacy of response rates to online and paper surveys: What can be done? Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2008, 33, 301–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Mishra, M.; Javed, H.M.U. The impact of mall personality and shopping value on shoppers’ well-being: Moderating role of compulsive shopping. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2021, 49, 1178–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common Method Biases in Behavioral Research: A Critical Review of the Literature and Recommended Remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeo, V.C.S.; Goh, S.K.; Rezaei, S. Consumer experiences, attitude and behavioral intention toward online food delivery (OFD) services. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2017, 35, 150–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polit, D.F.; Beck, C.T. Nursing Research: Generating and Assessing Evidence for Nursing Practice; LWW: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural Equation Modeling in Practice: A Review and Recommended Two-Step Approach. Psychlogical Bull. 1988, 103, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N.; Lynn, G.S. Lateral Collinearity and Misleading Results in Variance-Based SEM: An Illustration and Recommendations. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2012, 13, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Fit Indices in Covariance Structure Modeling: Sensitivity to Underparameterized Model Misspecification. Psychol. Methods 1998, 3, 424–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentler, P.M.; Bonett, D.G. Significance Tests and Goodness of Fit in the Analysis of Covariance Structures. Psychol. Bull. 1980, 88, 588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Erlbaum: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.J.; Hwang, J. Merging the norm activation model and the theory of planned behavior in the context of drone food delivery services: Does the level of product knowledge really matter? J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 42, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manosuthi, N.; Lee, J.S.; Han, H. Predicting the revisit intention of volunteer tourists using the merged model between the theory of planned behavior and norm activation model. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2020, 37, 510–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahid, H.; Ali, S.; Abu-Shanab, E.; Muhammad Usama Javed, H. Determinants of intention to use e-government services: An integrated marketing relation view. Telemat. Inform. 2022, 68, 101778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Item | Frequency | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 256 | 43.91 |

| Female | 327 | 56.09 | |

| Age | 20 or less than 20 | 32 | 5.49 |

| 21–25 | 165 | 28.30 | |

| 26–30 | 196 | 33.62 | |

| 31–35 | 118 | 20.24 | |

| 36–40 | 43 | 7.38 | |

| More than 41 | 29 | 4.97 | |

| Education level | High school or below | 51 | 8.75 |

| Junior college or university degree | 374 | 64.15 | |

| Postgraduate | 137 | 23.50 | |

| Other | 21 | 3.60 | |

| Monthly income in Renminbi (RMB) | Less than 2000 | 48 | 8.23 |

| 2001–3500 | 63 | 10.81 | |

| 3501–5000 | 99 | 16.98 | |

| 5001–6500 | 82 | 14.07 | |

| 6501–8000 | 129 | 22.13 | |

| More than 8000 | 162 | 27.79 | |

| Profession | Student | 162 | 27.79 |

| Corporate | 103 | 17.67 | |

| Government | 223 | 38.25 | |

| Freelancer or Business | 80 | 13.72 | |

| others | 14 | 2.40 |

| Items | Loadings | Cronbach Alpha | CR | AVE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Awareness of Consequences | AWCN1 | 0.806 | 0.723 | 0.833 | 0.625 |

| AWCN2 | 0.802 | ||||

| AWCN3 | 0.762 | ||||

| Ascription of Responsibility | ASRP1 | 0.745 | 0.718 | 0.840 | 0.569 |

| ASRP2 | 0.767 | ||||

| ASRP3 | 0.714 | ||||

| ASRP4 | 0.788 | ||||

| Personal Norm | PERN1 | 0.764 | 0.742 | 0.836 | 0.561 |

| PERN2 | 0.669 | ||||

| PERN3 | 0.815 | ||||

| PERN4 | 0.741 | ||||

| Sense of Mianzi | SMZI1 | 0.876 | 0.821 | 0.882 | 0.713 |

| SMZI2 | 0.855 | ||||

| SMZI3 | 0.801 | ||||

| Attitude | ATTI1 | 0.843 | 0.718 | 0.833 | 0.625 |

| ATTI2 | 0.781 | ||||

| ATTI3 | 0.745 | ||||

| Subjective Norm | SUBN1 | 0.680 | 0.755 | 0.778 | 0.543 |

| SUBN2 | 0.636 | ||||

| SUBN3 | 0.873 | ||||

| Perceived Behavior Control | PEBC1 | 0.818 | 0.877 | 0.891 | 0.731 |

| PEBC2 | 0.893 | ||||

| PEBC3 | 0.853 | ||||

| Food Over-ordering Intention | FOOI1 | 0.832 | 0.761 | 0.848 | 0.650 |

| FOOI2 | 0.813 | ||||

| FOOI3 | 0.772 |

| (a) | ||||||||

| ASRP | ATT | AWCN | FOOI | PEBC | PERN | SMZI | SUBN | |

| ASRP | 0.754 | |||||||

| ATT | 0.307 | 0.791 | ||||||

| AWCN | 0.357 | 0.443 | 0.79 | |||||

| FOOI | 0.435 | 0.628 | 0.41 | 0.806 | ||||

| PEBC | 0.254 | 0.313 | 0.371 | 0.419 | 0.855 | |||

| PERN | 0.466 | 0.586 | 0.419 | 0.671 | 0.323 | 0.749 | ||

| SMZI | 0.383 | 0.459 | 0.452 | 0.546 | 0.414 | 0.507 | 0.845 | |

| SUBN | 0.421 | 0.601 | 0.476 | 0.598 | 0.377 | 0.541 | 0.51 | 0.737 |

| (b) | ||||||||

| ASRP | ATT | AWCN | FOOI | PEBC | PERN | SMZI | SUBN | |

| ASRP | ||||||||

| ATT | 0.414 | |||||||

| AWCN | 0.481 | 0.627 | ||||||

| FOOI | 0.585 | 0.842 | 0.548 | |||||

| PEBC | 0.319 | 0.415 | 0.487 | 0.525 | ||||

| PERN | 0.614 | 0.773 | 0.557 | 0.789 | 0.41 | |||

| SMZI | 0.484 | 0.608 | 0.603 | 0.694 | 0.508 | 0.64 | ||

| SUBN | 0.569 | 0.786 | 0.708 | 0.72 | 0.49 | 0.658 | 0.68 | |

| H | Relationship | Beta Value | Stand Error | T Value | p Values | R2 | F2 | Q2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Awareness of Consequences -> Personal Norm | 0.289 | 0.039 | 7.410 | 0.000 | 0.290 | 0.103 | 0.158 |

| 2 | Ascription of Responsibility -> Personal Norm | 0.363 | 0.046 | 7.907 | 0.000 | 0.162 | ||

| 3 | Personal Norm -> Attitude | −0.475 | 0.037 | 12.765 | 0.000 | 0.378 | 0.270 | 0.231 |

| 4 | Attitude -> Food Over-Ordering _Intention | 0.395 | 0.038 | 10.513 | 0.000 | 0.197 | ||

| 5 | Subjective Norm -> Food Over-Ordering _Intention | 0.290 | 0.039 | 7.407 | 0.000 | 0.101 | ||

| 6 | Perceived Behavior Control -> Food Over-Ordering _Intention | 0.186 | 0.035 | 5.269 | 0.000 | 0.500 | 0.059 | 0.3058 |

| Moderating effect | ||||||||

| 7 | Sense of Mianzi -> Attitude | 0.052 | 0.026 | 1.990 | 0.024 | 0.401 | 0.006 | 0.233 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zheng, F.; Zhao, C.; Ajina, A.S.; Poulova, P. Decoding the Dilemma of Consumer Food Over-Ordering in Restaurants: An Augmented Theory of Planned Behavior Model Investigation. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8735. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15118735

Zheng F, Zhao C, Ajina AS, Poulova P. Decoding the Dilemma of Consumer Food Over-Ordering in Restaurants: An Augmented Theory of Planned Behavior Model Investigation. Sustainability. 2023; 15(11):8735. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15118735

Chicago/Turabian StyleZheng, Fei, Chenguang Zhao, Ahmad S. Ajina, and Petra Poulova. 2023. "Decoding the Dilemma of Consumer Food Over-Ordering in Restaurants: An Augmented Theory of Planned Behavior Model Investigation" Sustainability 15, no. 11: 8735. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15118735

APA StyleZheng, F., Zhao, C., Ajina, A. S., & Poulova, P. (2023). Decoding the Dilemma of Consumer Food Over-Ordering in Restaurants: An Augmented Theory of Planned Behavior Model Investigation. Sustainability, 15(11), 8735. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15118735