Analyzing the Development Possibilities of the Mountain Area of Banat, Caras-Severin County

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Research Methodology

2.1. Delimitation of the Researched Area—The Mountain Area of Banat, Caras-Severin County, Romania

2.2. Methods Used in Researching the Current Level of Tourism Development in Caras-Severin County and in Romania

- The number of tourist arrivals;

- The leisure stays (days);

- The annual revenues from tourism (million RON);

- Share of tourism in GDP (%).

- −

- The linear function y = at (1).

- −

- Power function y = atx (2).

- −

- The logarithmic function y = alog t (3).

- −

- The second-degree polynomial function y = rt2 ± bt ± c (4).

- −

- Higher degree polynomial function y = a1tn ± b2tn-1… ± an-1t ± an (5).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Analysis of Tourist Activities in Romania and in the Banat Mountain (Caraș-Severin County)

- −

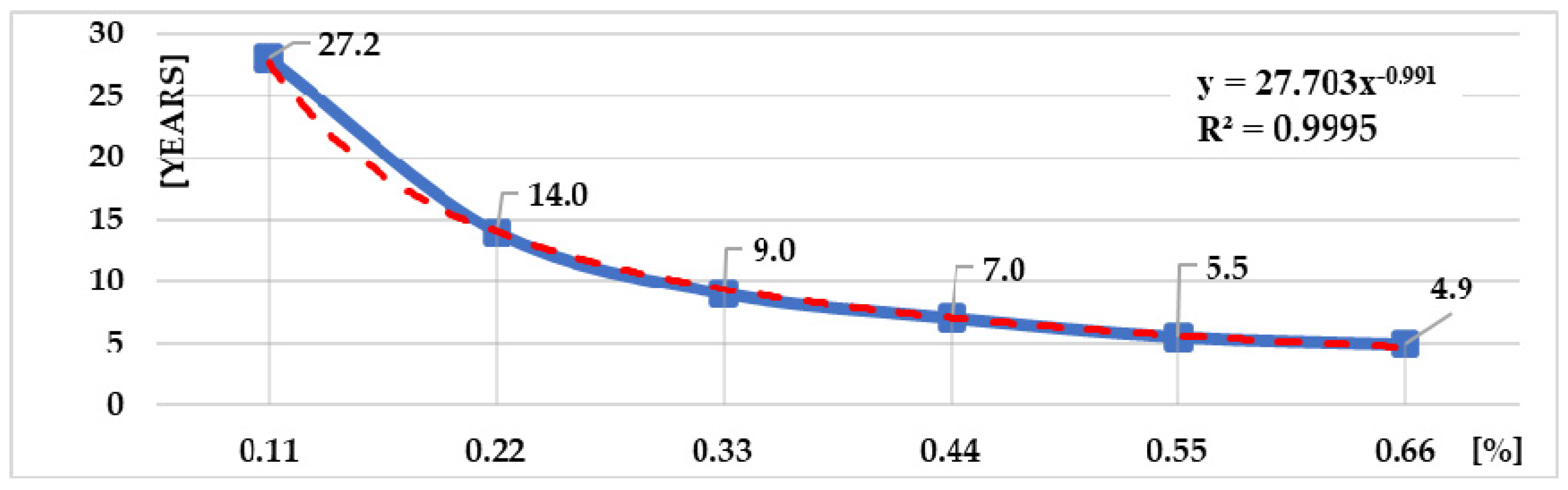

- The way in which current Romanian tourism is conceived (strategically) and its development is totally inappropriate, compared to the requirements of a modern, efficient and extensive tourism and to Romania’s exceptional natural tourist offerings. The fact that Romania has less than 1% of its GDP resulting from tourism is the most compelling figure demonstrating the “tourism precarity“ of our country.

- −

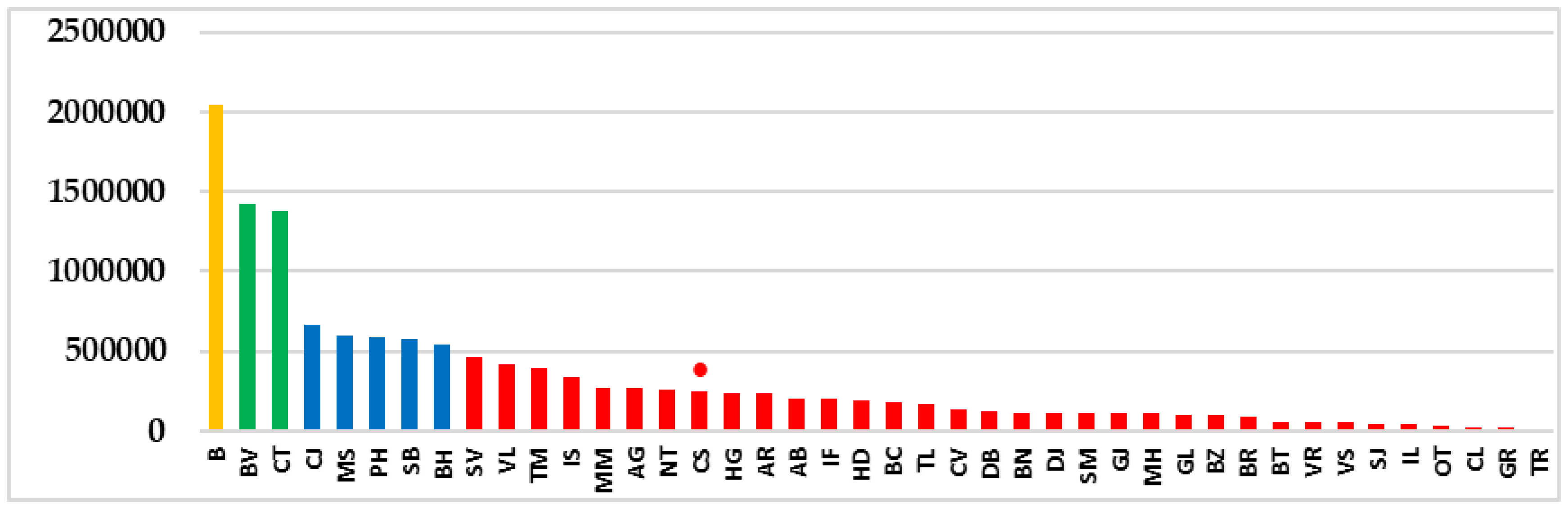

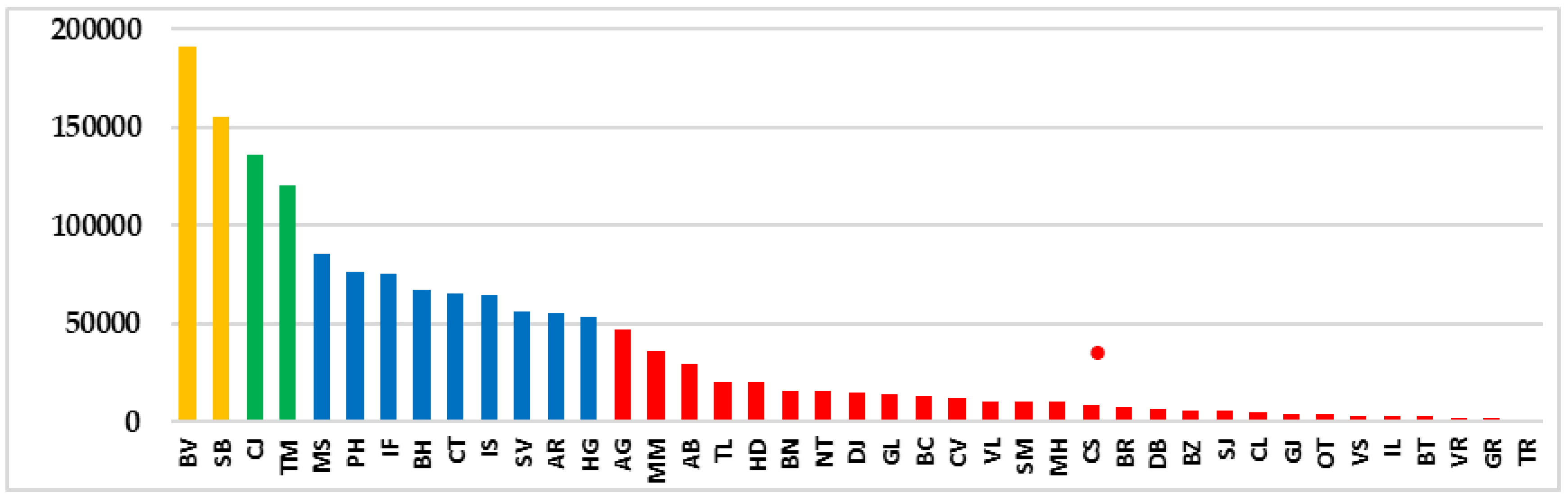

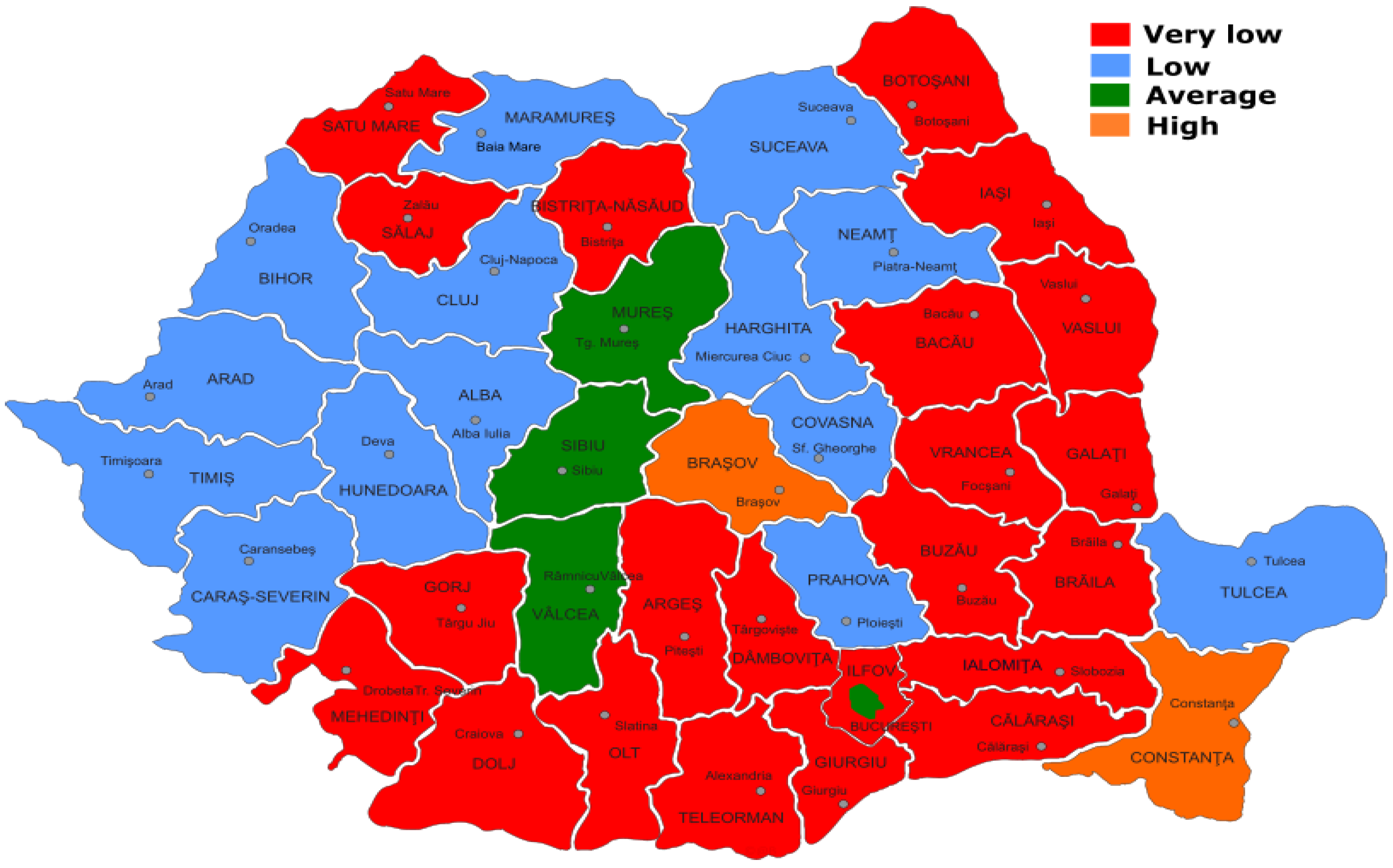

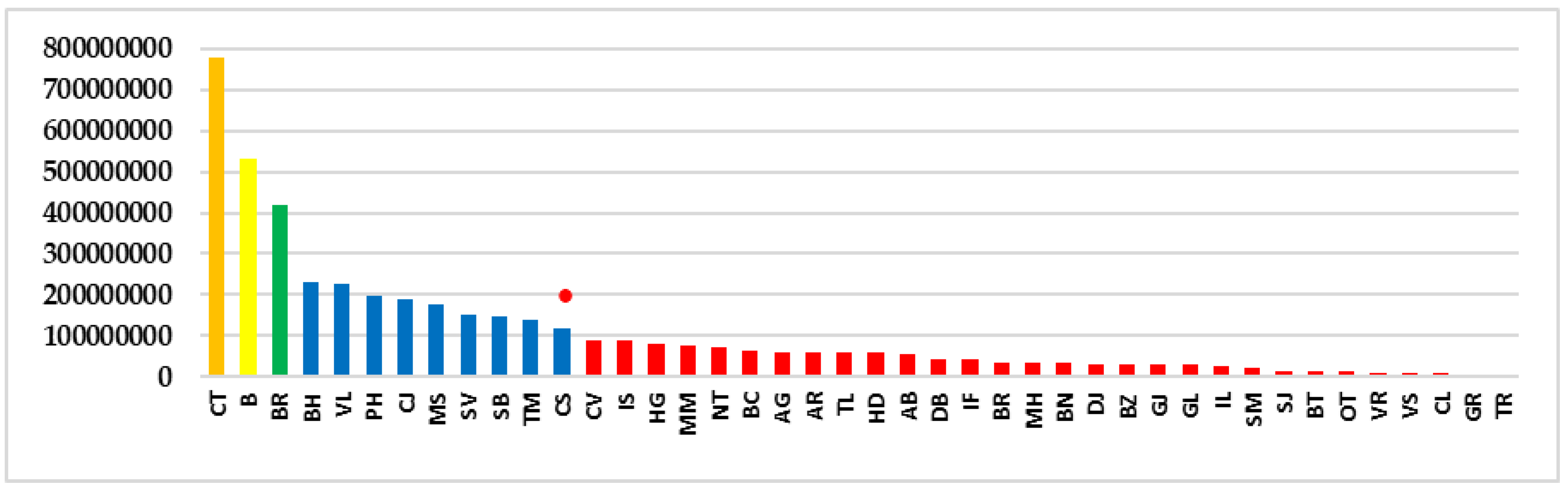

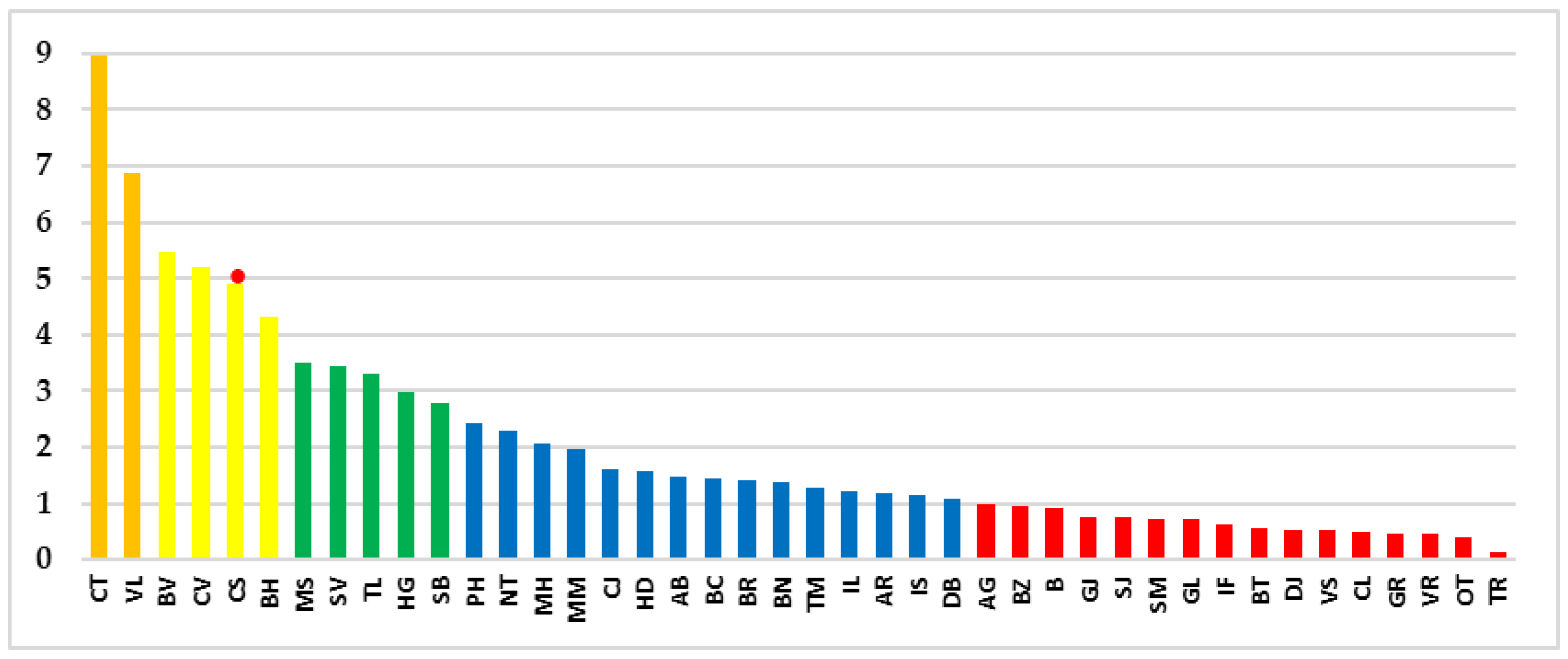

- On a national scale, on the country map, the development level of tourism is extremely dispersed. From the approximately EUR 4.5 billion in revenues from tourism in Romania in 2019, more than half was concentrated in five counties (Constanta, Brasov, Bihor, Valcea and Prahova) and the city of Bucharest. Each of these five counties has at least one area (point) of important tourist attraction, such as the coast in Constanta, Baile Felix in Bihor, the ski areas in Brasov, Olt Valley and the monasteries in Valcea and Prahova Valley in Prahova.

- −

- The country’s tourist counties (Maramures, Suceava, Tulcea, Sibiu and Caras-Severin), although they have exceptional natural (and to some extent also anthropic) tourist offerings, contribute only 17.1%, or RON 551 million (approx. EUR 110.2 million), to Romania’s tourism revenues. Although in these counties the tourist offerings are substantial (tradition in Maramures; the monasteries and Dornelor land in Suceava–Bucovina; the Danube Delta in Tulcea, and the European cultural capital Sibiu; the Herculane Baths and the Danube Gorge in Caras-Severin), their utilization is still far below their potential.

- −

- There are eight counties in Romania (a quarter of the country’s counties) where tourism is practically non-existent from an economic point of view (Teleorman, Giurgiu, Calarasi, Vaslui, Vrancea, Olt, Botoșani and Salaj), with annual revenues from tourism activity being under RON 20 million (approx. EUR 4 million) and under 100,000 annual overnight stays in each county.

- −

- At the current level of tourism in Caras-Severin County (relatively good numerically, 90.1 tourists/100 inhabitants), it is in the 10th place in the top counties, but an important remark that must be made is regarding the distribution of tourists by tourist destinations. Of the 244.6 thousand tourists registered in the period before the pandemic in Caras-Severin County, over 50% had as their destination the Herculane Baths resort, and 26% the Semenic and Muntele Mic ski areas, and only about 20% were there for other forms of tourism practiced in the mountain area of Banat.

- −

- Alarming for Caras-Severin County is the fact that rural tourism and agritourism are practically non-existent. Compared to Suceava and Maramures counties, agritourism in Caras-Severin is very poorly represented. While in Caras-Severin County the accommodation capacity in rural guesthouses and agritourist guesthouses represents 22% of the total county capacity, in Suceava county, for example, it is double that at 41%. In Suceava county, there are six communes (Dorna Candrenilor, Humor Monastery, Gura Humorului, Scheia, Sucevita and Vama) with over 300 accommodation places in the commune, while in Caras-Severin County there are only three communes (Valiug, Brebu Nou-Garana and Poiana Marului) falling into this category. However, in the communes of Suceava County, most of the rural guesthouses are agritourist guesthouses, while in Caras-Severin County, in this case in the communes of Valiug, Brebu Nou—Garana and Poiana Marului, there is no agritourist guesthouse, and there tourism is focused on the specific activity of “vacation villages”.

3.2. Identifying the Tourism Forms Practiced in the Mountain Area of Banat (Caras-Severin County)

- I.

- Mountain tourism

- II.

- Spa tourism

- III.

- Cultural Tourism

- IV.

- Agritourism

- V.

- Ethno-Cultural Tourism

- VI.

- Active Tourism in Protected Areas

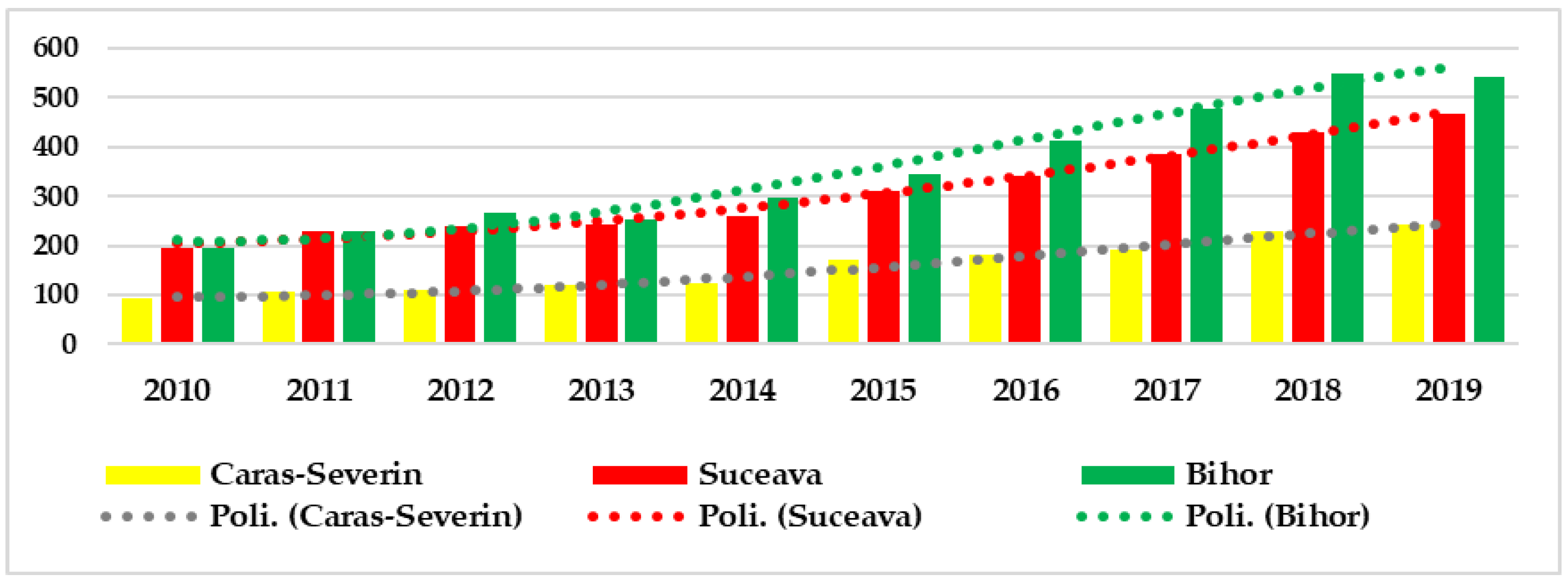

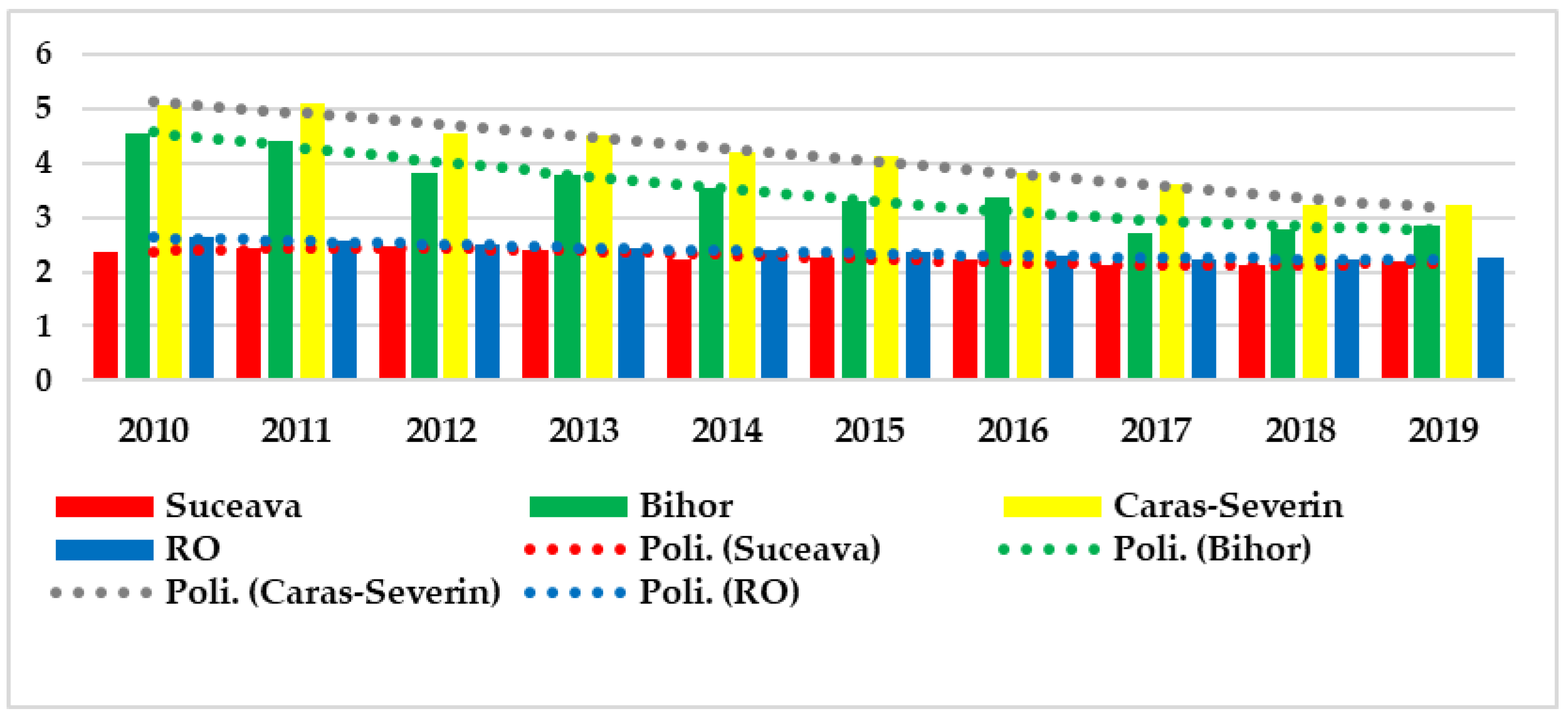

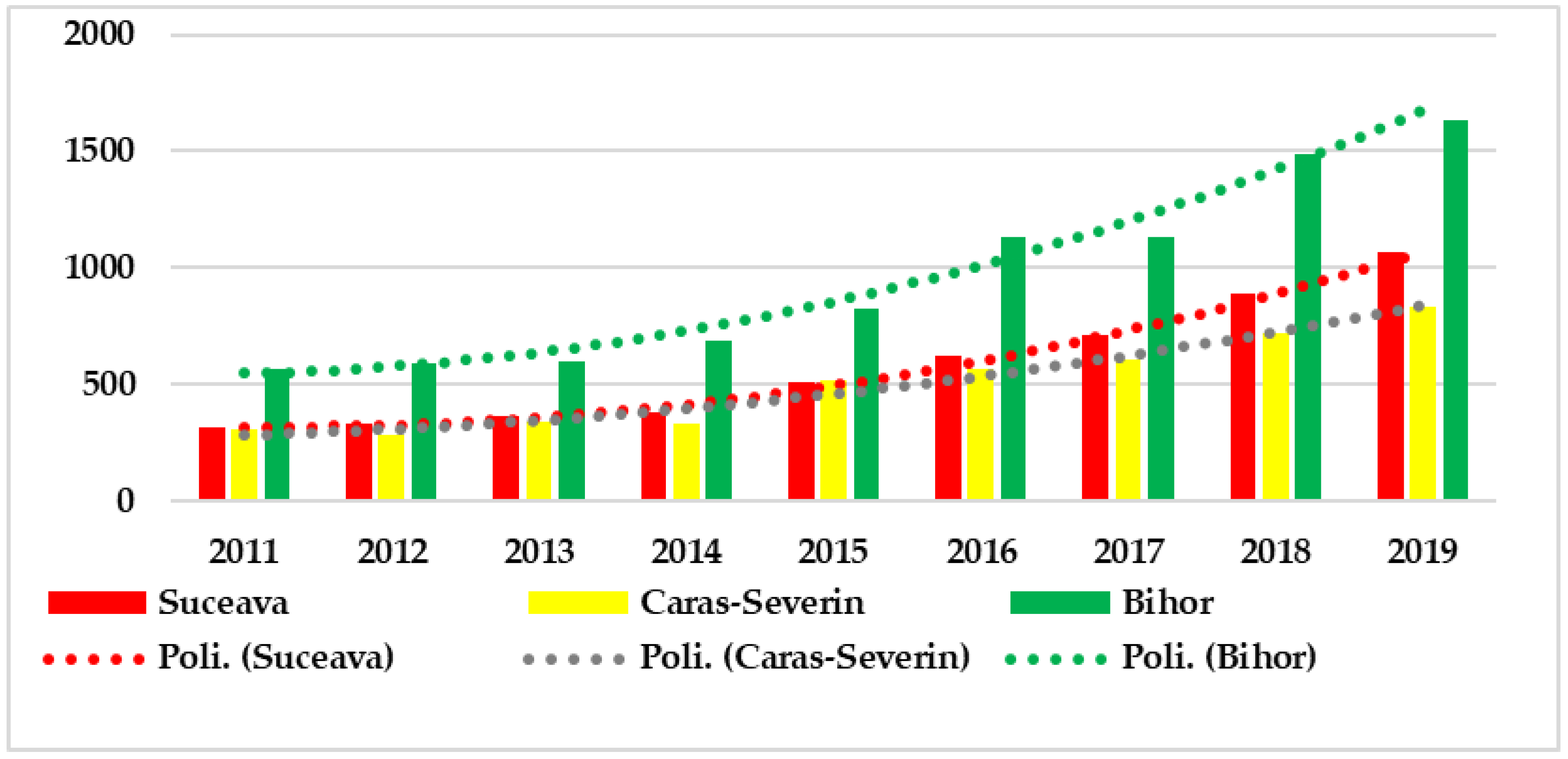

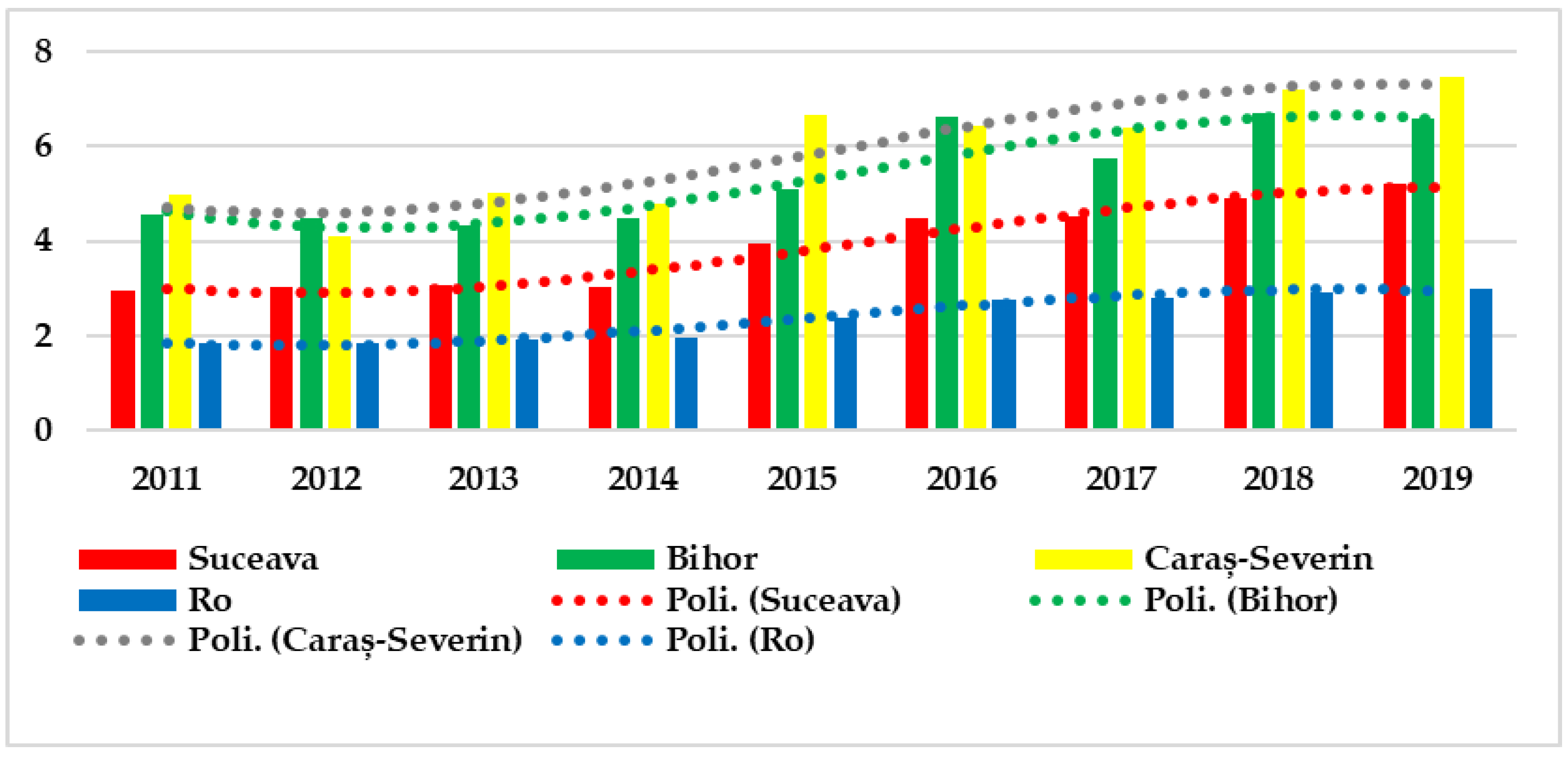

3.3. Comparative Forecasts of Tourism Development in Caras-Severin, Suceava and Bihor Counties and in Romania

| (1) The number of tourist arrivals, y1—polynomial function of the third degree. | |

| Caras-Severin | Y1C = −0.1411x3 + 3.5295x2 − 6.5609x + 99.912 |

| Suceava | Y1S = −0.0563x3 + 3.2773x2 − 0.1716x + 201.84 |

| Bihor | Y19 = −0.5409x3 + 11.411x2 − 26.453x + 226.31 |

| Romania | Y1R = −8.5158x3 + 164.53x2 − 65.306x + 6255.5 |

| (2) Length of stay 2000-2019, y2–polynomial function of the third degree. | |

| Suceava | Y2S = 0.0026x3−0.043x2 + 0.1618x + 2.2543 |

| Bihor | Y2B = 0.0012x3 − 0.0071x2 − 0.2558x + 4.823 |

| Caras-Severin | Y2C = 0.0006x3 − 0.0103x2 − 0.1748x + 5.308 |

| Romania | Y2R = 0.0004x3 −0.0028x2 − 0.0539x + 2.6843 |

| (3) The value of receipts from tourism, y3–polynomial function of the second degree. | |

| Suceava | Y3S = 12.473x2 − 31.156x + 337.6 |

| Caras-Severin | Y3C = 6.3519x2 + 6.1529x + 269.08 |

| Bihor | Y3B = 15.97x2 − 18.739x + 549.54 |

| Romania | Y3R = 258.36x2 + 211.12x + 9397.5 |

| (4) The share of tourism in GDP, y4–polynomial function of third degree. | |

| Suceava | Y4S = −0.0119x3 + 0.1957x2 − 0.6098x + 3.4367 |

| Bihor | Y4B = −0.0207x3 + 0.3318x2 − 1.1903x + 5.5137 |

| Caras-Severin | Y4C = −0.0169x3 + 0.2672x2 − 0.8071x + 5.2814 |

| Romania | Y4R = −0.0082x3 + 0.1256x2 − 0.3688x + 2.101 |

4. Conclusions

- On the water, on a cruise through the Danube Gorge from Moldova Noua to Orsova, through the most beautiful Danube Gorge, from the springs to the spill;

- By train, on the first mountain railway in Romania, Oravita-Anina in the Aurora Banatului tourist area and, at the same time, one of the most beautiful railways in operation in Europe;

- By car, to the Old “Mihai Eminescu” Theater in Oravita, the first theater in Romania, to the Rudaria Mills in the Aurora Banatului tourist area, and to the Rusca Montana Tourism Monument, unique in the world of tourism, in the Muntele Mic—Poiana Malului tourist area;

- By bicycle, on the mountain paths and former forest paths from Resita to the Comarnic Cave, in the Semenic tourist area;

- On foot, for a tour of the Herculane Baths resort, the oldest balneo-climatic resort in Romania and South-Eastern Europe, in the Nera-Beusnita Gorges, the longest and most beautiful gorges in Romania, in the Aurora Banatului tourist area and in the Carasului Gorges, the wildest in mountain Banat, in the Semenic tourist area.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adamowicz, M.; Zwoli’nska-Ligaj, M. New concept for rural development in the strategies and policies of the European Union. Econ. Reg. Stud. 2018, 11, 7–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, P.E. Tourism: A community Approach (RLE Tourism); Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kneafsey, M. Rural cultural economy: Tourism and Social Relations. Ann. Tour. Res. 2001, 28, 762–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z. Sustainable Tourism Development: A Critique. J. Sustain. Tour. 2003, 11, 459–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, A. Tourism in rural areas: Kedah, Malaysia. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 878–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bela, M.; Jovanović, D. Rural Tourism as A Factor of Integral and Sustainable Development of Rural Areas and Villages of Serbia and Voivodina. Her. J. Geogr. Reg. Plan. 2012, 1, 14–18. [Google Scholar]

- Bogan, E. Rural Tourism as a Strategic Option for Social and Economic Development in the Rural Area in Romania. Forum geografic. Stud. Cercet. Geogr. Protecția Mediu. 2012, 11, 37–43. [Google Scholar]

- Ciolac, R.; Iancu, T.; Brad, I.; Adamov, T.; Mateoc-Sîrb, N. Agritourism—A Business Reality of the Moment for Romanian Rural Area’s Sustainability. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatipoglu, B.; Ertuna, B.; Salman, D. Small-sized tourism projects in rural areas: The compounding effects on societal wellbeing. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 30, 2121–2143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nistoreanu, P. Turismul Rural-o Afacere Mică cu Perspective Mari; Editura Didactică şi Pedagogică: Bucureşti, Romania, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, M.; Hens, L.; Ou, X.; De Wulf, R. Tourism: An Alternative to Development? Reconsidering Farming, Tourism, and Conservation Incentives in Northwest Yunnan Mountain Communities. Mt. Res. Dev. 2009, 29, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, M.M.; Haines, A. Evaluating smart growth: Implications for small communities. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2007, 27, 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateoc-Sîrb, N.; Otiman, P.I.; Mateoc, T. The Evolution of Romanian Villages Since the Great Union of 1918. Transylv. Rev. 2018, 27, 249–261. [Google Scholar]

- Gajić, T.; Vukolić, D.; Petrović, M.; Blešić, I.; Zrnić, M.; Cvijanović, D.; Sekulić, D.; Spasojević, A.; Obradovi, A.; Obradović, M.; et al. Risks in the Role of Co-Creating the Future of Tourism in “Stigmatized” Destinations. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masot, A.N.; Gascón, J.L.G. Sustainable Rural Development: Strategies, Good Practices and Opportunities. Land 2021, 10, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sneddon, C.; Howarth, R.B. Norgaard Sustainable development in a post-Brundtland world. Ecol. Econ. 2006, 57, 253–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lekić, O.Z.; Gadžić, N.; Milovanović, A. Sustainability of rural areas—Exploring values, challenges and socio-cultural role. In Sustainability and Resilience—Socio-Spatial Perspective; Fikfak, A., Kosanović, S., Konjar, M., Anguillari, E., Eds.; TU Delft Open: Delft, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 171–184. [Google Scholar]

- Waligo, V.M.; Clarke, J.; Hawkins, R. Implementing sustainable tourism: A multi-stakeholder involvement management framework. Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 342–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liburd, J.J.; Edwards, D. Understanding the Sustainable Development of Tourism; Goodfellow Publishers Limited: Oxford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Munjal, S.; Munjal, P.G. Sustainable Tourist Destinations: Creation and Development. In Managing Sustainability in the Hospitality and Tourism Industry Paradigms and DIrections for the Future; Taylor & Francis Group: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2014; pp. 227–272. [Google Scholar]

- Dax, T.; Fischer, M. An alternative policy approach to rural development in regions facing population decline. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2017, 26, 297–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramwell, B. Rural tourism and sustainable rural tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 1994, 2, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nidumolu, R.; Prahalad, C.K.; Rangaswami, M.R. Why sustainability is now the key driver of innovation. Harvard Bus. Rev. 2009, 87, 56–64. [Google Scholar]

- Ciolac, R.; Adamov, T.; Iancu, T.; Popescu, G.; Lile, R.; Rujescu, C.; Marin, D. Agritourism-a sustainable development factor for improving the ‘health’ of rural settlements. Case study Apuseni Mountains area. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, R. The political economy of tourism development: A critical review. Ann. Tour. Res. 2018, 70, 88–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toivonen, A. Sustainability dimensions in space tourism: The case of Finland. J. Sustain. Tour. 2022, 30, 2223–2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tourism and the Sustainable Development Goals—Journey to 2030. Available online: https://www.unwto.org/global/publication/tourism-and-sustainable-development-goals-journey-2030 (accessed on 29 August 2022).

- Alhasni, Z.S. Tourism Versus Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) Tourism—An Element of Economic Growth of Metropolitan Cities. Entrepreneurs. Estud. Econ. Appl. 2021, 39, 1133–3197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, B. Sustainable rural tourism strategies: A tool for development and conservation. J. Sustain. Tour. 1994, 2, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunkoo, R.; Sharma, A.; Rana, N.P.; Dwivedi, Y.K.; Sunnassee, V.A. Advancing sustainable development goals through interdisciplinarity in sustainable tourism research. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 31, 735–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comisia Europeană. O Selecție a Celor Mai Bune Practici Leader+; Comisia Europeană: Brussels, Belgium, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- National Rural Development Network (RNDR). Bune Practici, 2014, No. 4 Anul II, USR, Departamentul Publicaţii MADR. Available online: http://madr.ro (accessed on 16 February 2023).

- Euromontana. Către Dezvoltarea Integrată a Zonelor de Munte si Recunoasterea Acestora în Cadrul PAC-Modelarea Noului Spatiu European; Euromontana: Brussels, Belgium, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Popescu, G.; Popescu, C.A.; Iancu, T.; Brad, I.; Peț, E.; Adamov, T.; Ciolac, R. Sustainability through Rural Tourism in Moieciu Area-Development Analysis and Future Proposals. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciolac, R.; Iancu, T.; Popescu, G.; Adamov, T.; Feher, A.; Stanciu, S. Smart Tourist Village—An Entrepreneurial Necessity for Maramures Rural Area. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamov, T.; Iancu, T.; Peț, E.; Popescu, G.; Șmuleac, L.; Feher, A.; Ciolac, R. Rural Tourism in Marginimea Sibiului Area—A Possibility of Capitalizing on Local Resources. Sustainability 2023, 15, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajić, T.; Blešić, I.; Petrović, M.D.; Radovanovć, M.M.; Đoković, F.; Demirović Bajrami, D.; Kovačić, S.; Jošanov Vrgović, I.; Tretyakova, T.N.; Syromiatnikova, J.A. Stereotypes and Prejudices as (Non) Attractors for Willingness to Revisit Tourist-Spatial Hotspots in Serbia. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kürüm Varolgüne, F.; Çelik, F.; Del Río-Rama, M.C.; Álvarez-García, J. Reassessment of sustainable rural tourism strategies after COVID-19. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 944412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beteille, R. La Valorisation Touristique de l’Espace Rural; University of Poitiers: Poiters, France, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Li, Y. Revitalize the world’s countryside. Nature 2017, 548, 275–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seraphin, H. Tourism: How to achieve the sustainable development goals? Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2021, 13, 3–8. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, R.; Hall, M.; Jenkis, J. Tourism and Recreation in Rural Areas; John Wiley and Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Garrod, B.; Wornell, R.; Youell, R. Re-conceptualising rural resources as countryside capital: The case of rural tourism. J. Rural. Stud. 2006, 22, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iancu, T.; Petre, I.L.; Tudor, V.C.; Micu, M.M.; Ursu, A.; Teodorescu, F.-R.; Dumitru, E.A. A Difficult Pattern to Change in Romania, the Perspective of Socio-Economic Development. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institutul Național de Statistică (INS). Available online: https://insse.ro/cms/ro (accessed on 25 November 2022).

- Stake, R.E. Multiple Case Study Analysis; Guildford: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods; Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Available online: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2022/01/davos-2022-world-economic-forum-annual-meeting (accessed on 12 April 2023).

| Place | County | EUR (Millions) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | ||

| 1 | Cluj | 9425 | 10,308 | 11,641 |

| 2 | Timis | 8525 | 9615 | 10,822 |

| 30 | Caras-Severin | 2087 | 2164 | 2408 |

| 41 | Covasna | 1404 | 1578 | 1742 |

| 42 | Giurgiu | 1195 | 1676 | 1499 |

| Romania | 4319 | 4364 | 4841 | |

| Place | County | EUR | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | ||

| 1 | Cluj | 13,411 | 14,628 | 16,466 |

| 2 | Timis | 12,209 | 13,707 | 15,344 |

| 21 | Caras-Severin | 7478 | 7866 | 8873 |

| 41 | Covasna | 4823 | 8494 | 6182 |

| 42 | Giurgiu | 449 | 5026 | 5433 |

| Romania | 7791 | 9560 | 10,666 | |

| Place | County | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ilfov | 4165 | 4451 | 5188 |

| 2 | Timis | 3998 | 4359 | 4386 |

| 30 | Caras-Severin | 287 | 162 | 196 |

| 41 | Mehedinti | 5 | 16 | 19 |

| 42 | Gorj | 4 | 3 | 3 |

| Romania | 1709 | 1797 | 1965 |

| Place | County | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Timis | 6292 | 6901 | 7307 |

| 2 | Arges | 6022 | 6240 | 6226 |

| 30 | Caras-Severin | 317 | 347 | 360 |

| 41 | Giurgiu | 76 | 85 | 73 |

| 42 | Gorj | 54 | 65 | 68 |

| Romania | 1492 | 1612 | 1643 |

| Place | County | Km2 |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Timis | 869,665 |

| 2 | Suceava | 855,350 |

| 3 | Caras-Severin | 851,976 |

| 41 | Giurgiu | 352,602 |

| 42 | Ilfov | 158,328 |

| Place | County | No. People |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Iasi | 792,131 |

| 2 | Prahova | 725,515 |

| 3 | Cluj | 704,784 |

| 4 | Timis | 701,690 |

| 36 | Caras-Severin | 275,181 |

| 41 | Covasna | 203,504 |

| 42 | Tulcea | 195,626 |

| Place | County | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 13 | Caraș-Severin | 2087 | 2164 | 2408 |

| 21 | Hunedoara | 2964 | 3236 | 8671 |

| 30 | Arad | 4128 | 4539 | 5055 |

| 41 | Timis | 8525 | 9615 | 10,822 |

| Place | County | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 22 | Caraș-Severin | 7478 | 7866 | 8873 |

| 30 | Hunedoara | 7550 | 8328 | 9564 |

| 34 | Arad | 9782 | 10,830 | 12,114 |

| 41 | Timis | 12,209 | 13,707 | 15,344 |

| County | Total Mill. EUR | Advantage Mill. EUR | CA/Employee EUR | Advantage EUR/Employee |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Timis | 16,335 | 1221 | 76,695 | 5730 |

| Arad | 6814 | 465 | 75,994 | 5166 |

| Hunedoara | 771 | 220 | 44,089 | 3507 |

| Caras-Severin | 1442 | 116 | 47,183 | 3786 |

| Country | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Romania | 13 | 19 | 19 |

| Bulgaria | 59 | 64 | 65 |

| Croatia | 381 | 408 | 433 |

| Slovenia | 177 | 202 | 234 |

| Serbia | 57 | 59 | 60 |

| Caras-Severin County | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Cultural–historical tourism | Consists of visiting historical monuments and ensembles, as well as archaeological sites in Caras-Severin County | Tibiscum Camp in Jupa-Caransebes, Roman baths in the Herculane Baths, Tabula Traiana in Cazanele Dunarii, the remains of the Villa Rustica in Gornea, Sichevita commune, etc. |

| Cultural–architectural tourism | Aims to visit some monuments and architectural ensembles in Caras-Severin County | The “Mihai Eminescu” Old Theater building in Oravita, the Cultural Palace in Resita, the Palace of the Community of Wealth in Caransebes, the Baroque-style historical center of Herculane Baths resort, the Baroque-style train station in Herculane Baths, the Oravița train station, the Caransebes Town Hall building, etc. |

| Cultural–museum tourism | Means visiting historical, ethnographic, art, archaeology, natural sciences, science and technology, memorials and village museums in Caras-Severin County | The Mountain Banatul Museum in Resita, the County Museum of Ethnography and of the Border Regiment in Caransebes, the Station Museum in Baile Herculane, the Open Air Steam Locomotive Museum in Resita, the “Constantin Gruescu” Iron Mineralogy Collection in Resita, the Museum of the Amateur Cinematographer, and the village museums in Bania, Cornea, Gornea, Mehadica and Racasdia. |

| Cultural–scientific tourism | Involves exploration and scientific discovery in Caras-Severin County | Aiming at the past (visiting archaeological sites), the present (visiting active enterprises and industrial parks) and the future (visiting the UBB Cluj Research Center–University Campus of Summer in Coronini/Resita). |

| Cultural–religious tourism | Aims at pilgrimage and visiting monasteries, hermitages, churches and cathedrals in Caras-Severin County and the Orsova area | Calugara Monastery in Ciclova Montana, Piatra Scrisa Monastery in Armenis, Vasiova-Izvor Monastery in Bocsa, Teius Monastery in Caransebes, Saint Ana Monastery in Orsova, Mraconia Monastery in Dubova, Brebu Monastery in Brebu-Soceni, Slatina Nera Monastery in Sasca Montana, Almaj-Putna Monastery in Putna-Prigor, Bazias Monastery, “ St. Elijah “ Hermitage in Mount Semenic, Poiana Mărului Hermitage, the translated Orthodox Church in Resita, the “Immaculate Conception” Catholic Church in Orsova, the Gothic-style synagogue in Caransebes, the Episcopal Cathedral in Caransebes, the collection of religious art in the Caransebes Bishopric Building. |

| Cultural–industrial tourism | Is linked to visiting many unique industrial and technical sites in the mountain area of Banat | The first railway in Romania at Oravita–Bazias, the Oravita viaduct, the first mountain railway in Romania at Oravita–Anina, the open-air museum of steam locomotives in Resita, artificial lakes in Barzava and Timis (Secu, Breazova-Valiug, Gozna-Crivaia, Trei Ape), first well of the deepest mine (1000 m) in Europe in Anina, marble quarry in Ruschita, the water mills with a horizontal wheel at Valea Rudariei, in Moceris and Sichevita, the Furnace and the Funicular in Resita, etc. |

| Cultural–ethnographic and folkloric tourism | Can be practiced on the occasion of original and authentic folklore events in Caras-Severin County | The “Hercules” International Folklore Festival at the Herculane baths resort, the Almaju Country Festival, the Gugulani Country Festival, as well as the ”nedei” (prayers) which, from spring until late autumn, are held in all Banat villages with Orthodox churches that have patron saints, with specific religious and secular traditions and customs. |

| Cultural–artistic tourism | Focused on festivals and cultural–artistic events throughout the year in Caras-Severin County | Jazz Festival in Garana, “Mihai Eminescu” Days in Oravita, the “Crystal Palette” painting colony in Garana, the sculpture camp in Teius park in Caransebes, the “Decade of German Culture” event in Resita, the gastronomic festival “The Golden Cauldron” in Moldova Noua, etc. To these is added the “Days of Culture” in each city of Caras-Severin County. |

| Cultural–ethnic tourism | Can be practiced through the multiculturality of mountain area of Banat on tourist routes specific to each ethnic folklore | The German folklore route, the Croatian folklore route, the Serbian folklore route, the Czech folklore route, the Ukrainian folklore route, the Hungarian folklore route, etc. |

| Cultural–itinerant tourism | Can be carried out in the form of thematic circuits through several localities in Caras-Severin County | The Iron Way or the Road of the Romans, etc. |

| The rural settlement of mountain towns in Banat, the construction and decoration of the peasant houses | In the mountain area there are valley towns, located on the edge of a river and along the roads | Cornereva is the largest locality in Romania, with 36 hamlets, the most famous of which is Inelet because of the access stairs in the hamlet, followed by Sichevita with 19 hamlets |

| Traditional technical installations | A special place is occupied by the “water mills” with a horizontal wheel (with bucket) | In Rudăria (gutter and bucket mills) and Sichevita, Moceris, Sopotu Vechi and Valea Rosie-Sopotu Nou (bucket and cufflink mills) |

| The folk costume | This is a true “visiting card” of Banat villages, being a clothing ensemble with distinct pieces of clothing and ornaments, of great artistic value | Costumes of the Gugulani, Almajeni and Carasovani; a particular attraction is the specific holiday costume, which includes many decorative and chromatic elements |

| The folk art of woodcraft | The use of wood and its processing in various forms was done according to the needs of the household and the artistic sense of the folk craftsmen | The “wooden cradle” for carrying children on the back can rightly be considered one of the most interesting and beautiful creations of the craftsmen in the Nera Valley and the Danube Gorge |

| The popular art of marble processing | The existence of the marble quarry favored the artistic processing of marble and the presence of some elements in the construction of houses (pillars, stairs, marble tables, floors) and funerary pieces | In Ruschita |

| The popular art of metalworking | The steel and cast-iron embroideries | That on the bridges over the Cerna, at Băile Herculane and in the construction of house fences in Rusca Montană (craftsman Ilie Nicoară), as well as funerary pieces, stand out |

| The folk art of leather processing | The art of leather processing had an exceptional development until the 1980s–1990s | There are fewer and fewer craftsmen who deal with leather and shoemaking (Valisoara, Cornea, Cuptoare) and who make leather shoes, jackets, hats, all impressive in their decoration and style |

| The art of fabrics, stitches and embroidery | Popular pieces | Sewn by the skillful hands of the Banat woman, constitutes a true Carasan folk art |

| The art of pottery | From the Roman ceramics | In Binis |

| The art of braiding | Various hand-woven objects | In Carasova |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Peev-Otiman, P.-D.; Mateoc-Sîrb, N. Analyzing the Development Possibilities of the Mountain Area of Banat, Caras-Severin County. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8730. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15118730

Peev-Otiman P-D, Mateoc-Sîrb N. Analyzing the Development Possibilities of the Mountain Area of Banat, Caras-Severin County. Sustainability. 2023; 15(11):8730. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15118730

Chicago/Turabian StylePeev-Otiman, Paula-Diana, and Nicoleta Mateoc-Sîrb. 2023. "Analyzing the Development Possibilities of the Mountain Area of Banat, Caras-Severin County" Sustainability 15, no. 11: 8730. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15118730

APA StylePeev-Otiman, P.-D., & Mateoc-Sîrb, N. (2023). Analyzing the Development Possibilities of the Mountain Area of Banat, Caras-Severin County. Sustainability, 15(11), 8730. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15118730