Abstract

The study aims to determine the understanding and perception of working conditions perceived by platform workers in terms of work/life balance and the quality of life. In addition, this current study empirically analyzes their perception on the structural relationship amongst work and life balance and the quality of life. The study uses quality of life and work/life balance to build a conceptual model, and questionnaires were collected through an online survey of 447 gig workers using a convenience sampling method. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was employed to investigate the adequacy of the measurement model, and structural equation modeling (SEM) was performed along with the maximum likelihood method to examine relationships amongst the seven constructs in the proposed model. The study results show there were statistically significant values in five paths (working environment → overall QOL; leisure domain → overall QOL; economic domain → overall QOL; emotional domain → overall QOL; and overall QOL → psychological well-being), except for ‘social support → overall QoL’. It was found that the economic and emotional factors that belong to the life domain had more impact on the overall quality of life than the components of the ‘work category’. Implications for future research and the work environment perceived by gig workers for the platform market are discussed.

1. Introduction

The Fourth Industrial Revolution and the emergence of the digital platform have brought about innovative changes in the e-commerce logistics market [1,2,3]. The digital platform is online-to-offline (O2O), which induces service providers and consumers to a virtual digital space to provide information and content services, commercial transactions and intermediation, etc., and create new values [4]. Gig work based on the digital platform allows startups to compete with existing businesses by lowering the costs of market access [3]. This platform work is non-standard work, a new form of labor in the digital era, and gig workers are engaged in non-standard labor, such as temporary employment, dispatched work, and multi-party employment contracts. Hence, gig work is a type of work that earns labor income based on the digital platform without signing employment contracts [3,5]. Platform labor can be seen as a new typical labor in the digital circumstance, and jobs are obtained through digital platforms, and a certain amount of money is received per irregular job [6].

The value of food delivery transactions amid COVID-19 amounted to KRW 20 trillion as of 2020, increasing by 43% from 2019 [7]. Despite such market expansion, problems with the work conditions of delivery workers, such as low wage, and weekend and nighttime work, have emerged, leading to more discussions about the improvement of the working conditions for gig workers. Moreover, it was noted that as gig workers are not working in a formal working environment, they are in an inferior working environment, and thus it is necessary to identify the status of gig workers, and improve the work conditions for gig workers [8].

In the academic community and businesses, there is ongoing research on new employment patterns under the Fourth Industrial Revolution. Early studies focused on changes in the labor environment due to the development of ICT. The automation of industrial robots would lead to changes in the labor market, such as the decrease in unskilled labor [9,10]. Prior work predicted insecurity in the labor market, arguing that the labor environment in the digital era would result in stagnant wages, a decline in labor participation, a reduction in job creation, and deepening inequity [2]. Meanwhile, some studies noted changes in the labor market due to the Fourth Industrial Revolution [1,6]. The rise of digital special employees who, amid the Fourth Industrial Revolution, rely on intermediated employment relations, outside of the standard employer–employee relationship, and perform fragmentary work is called gig work [3].

Most of the literature has focused on changes in the labor market, status analysis, and policy issues, without an understanding of job insecurity, task instability, and inferior quality of life experienced by gig workers. Thus, with the transformation in labor market due to the Fourth Industrial Revolution and expansion of the labor market platform, the current study aims to examine the understanding and perception of working conditions perceived by gig workers, one of the stakeholders of the labor market in terms of work/life balance and the quality of life. Two theories, work/life balance and quality of life, are meaningful indicators of the well-being of workers. Work/life balance is directly related to the quality of life and competitiveness of workers through a stable working environment and harmony with private life [9,11,12], and the work/life balance is a topic appropriate to assess the working environment and the quality of life for gig workers in the food industry field [13,14]. To achieve the purpose, the present study investigated gig worker’s psychological attitudes and aspects towards their quality of life and work environment balance through interviews. Then, this study assessed the causality between work and life balance and the quality of life for gig workers in various aspects, and empirically analyzed their perception on the structural relationship among work and life balance and the quality of life. Based on the results, this research proposes ways of improving the employment ecosystem and suggests improvements in job stability and quality of life for gig workers.

2. Conceptual Framework

2.1. Work/Life Balance (WLB)

Work/life balance refers to the optimal allocation of time and psychological and physical energy between work and non-work concerns, such as life, leisure/health, and growth/self-development, enabling individuals to control and be satisfied with their lives [15,16]. Lately, work/life balance has drawn attention, and become an important issue for both individuals and organizations, because work/life conflicts of individuals bring about negative results to individuals and organizations [17,18]. In particular, the literature has found that employees who secured time and spatial resources in work and life can relieve or reduce work/life conflicts associated with family roles, such as house chores and child rearing, and that an organization assigning employees a leeway of time and space in performing their tasks is perceived as a message of the organization’s intention to build confidence, instead of controlling them, resulting in increased loyalty [17].

Prior studies have measured the work/life balance in multiple dimensions. A past study stressed the importance of leading a satisfactory, healthy, and productive life, and measured the level of balance between two categories: work and play [19]. The work analyzed this balance in five categories: work, family, community, region, and leisure [20]. Greenhaus and Powell (2006) [16] studied the notion of balance in three areas: time balance, psychological involvement balance, and satisfaction balance to achieve work/non-work objectives.

2.2. Quality of Life (QoL)

In the literature, the quality of life has practical purposes, and is divided into well-being, welfare, and happiness, and the quality of life has been used as the theme of research in various sectors [11,12,16]. The literature found that the quality of life includes subjective and psychological factors individuals experience in human relationships in a system and social structure, and the impact of social conditions and institutions on the lives of individuals is also one of the determinants of the quality of life [18,20].

The literature on the quality of life dealt with subfactors or determinants of the quality of life [16], the development of an objective and subjective measure of the quality of life and measurement [21], and the measurement of the quality of life and comparative analysis [22,23]. Depending on the purpose of measuring the quality of life, only the materialistic living conditions were measured, or the subjective quality of life was assigned more weight in the measurement of the quality of life. However, the overall quality of life covers physical, emotional, and overall categories. The literature maintained that the OECD Better Life Index (BLI) emphasized the multi-dimensional characteristics of the quality of life and the microscopic aspect of personal life, and consisted of physical living conditions and the subjective quality of life [24,25]. Here, physical living condition domains include income, type of residence, and job, while the quality-of-life domain includes subjective living conditions, such as leisure, health, education, environment, civic engagement, social networks, healthcare, and safety [24,25].

Sirgy (2002, 2011) [11,12] defined the quality of life as overall life satisfaction, and suggested that the quality of life needs to be measured in multi-dimensional perspectives. Sirgy (2002) [11] used a bottom–up theory to measure the quality of life. The bottom–up theory views overall life satisfaction as a function of diverse factors, such as family, society, leisure, finance, community, and mental life, and proposes that if individuals value life in specific areas, more diverse factors should be reflected in the assessment of overall life quality. That is, the bottom–up theory basically maintains that life satisfaction is determined by life domain satisfaction, and the components of the sub areas of life domain satisfaction and the sub areas of overall life satisfaction need to be noted.

Studies on the measurement of the quality of life using bottom–up theory have been made in various areas. Rahman et al. (2005) [26] reviewed the literature on well-being, and listed eight life domains as sub factors affecting the quality of life: health, work, economic ability, relationship with residents, safety, emotional well-being, environment, and relationship with friends and family. A past study divided the sub factors of life satisfaction into the economic area and non-economic areas to measure the quality of life of stakeholders in the tourism industry, and observed that the non-economic areas cover community, emotional well-being, and health and safety [27].

3. Methods

3.1. Proposed Framework and Hypotheses

A number of previous studies investigated the relationship between individuals’ life domain satisfaction and their quality of life. Before the conceptual model was designed, the qualitative interview was performed to establish in-depth understanding of gig workers’ perception of working conditions and their quality of life [28]. A snowball sampling method for the in-depth interviews was adopted. A few potential respondents were initially contacted and then asked whether they knew of anyone with the characteristics.

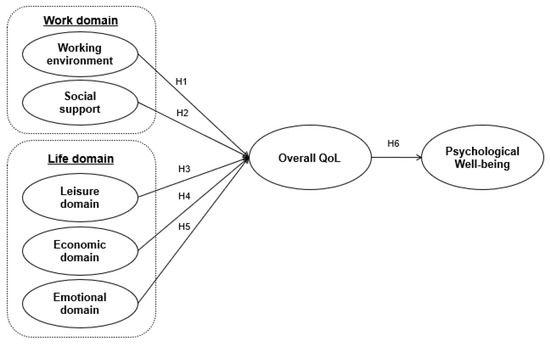

This interview was carried out with 10 participants from 9 March to 25 April 2021, and the interviews lasted around 60 min. The intention of the interview was to categorize the constructs of gig workers’ work domain and life domain. The findings of the qualitative study were classified into two categories, ‘work domain’ and ‘life domain’. Work domain factors included ‘working environment’ and ‘social support’, and life domain factors contained ‘leisure domain’, ‘economic domain’, and ‘emotional domain’. Based on the review of recent research and the interview results, the proposed model is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Proposed research model.

According to the results of the in-depth interview, the work domain factor was classified into two categories: working environment and social support. Previous research has demonstrated a critical problem requiring employees’ work stability can explain the possible relationships amongst social support, positive workplace, and quality of life to lead to direct effects involving overall quality of life [29,30]. Prior studies mentioned that employees who are satisfied with their job environment and their quality of life are anticipated to contribute to the organization [29]. In addition, past research stated that social support for workers is related to their work satisfaction, principally because it is obviously related to a better overall quality of life [30,31]. Palumbo (2020) [32] indicated that the working environment includes employment quality, diversity, and training opportunity components affecting employees’ satisfaction in their workplace. According to Cobb (1976) [33] (p. 300), social support is ‘information leading the subject to believe that he is cared for and loved, esteemed, and a member of a network of mutual obligations’. Furthermore, Vangelisti (2009) [31] pointed out that social support can be defined as positive interpersonal relationships with other people, from sociological and communication aspects.

The related literature has confirmed this relationship amongst working environment, social support, and quality of life. Sirgy’s work provided that an individual regards work life as a psychological perspective wherein the experiences related to work are stored, and the experiences can improve his/her overall quality of life [11,12]. Past studies showed the significance effect of quality of the working environment on employees’ positive psychological circumstances [16,34]. Narehan et al. (2014) [34] stressed the necessity of quality of work life programs concerning employees’ working conditions with objectives to improve employees’ satisfaction. In addition, this research revealed that improvement of the job environment can influence workers’ quality of life while Finch & Graziano (2001) [35] mentioned that perceived social support can influence the level of an individual’s emotional condition. An individual with a high perception of others’ social support is positively related to his/her perceived overall life satisfaction. From this point of view, this study suggests the following hypotheses.

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

The working environment is associated with overall QoL.

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

Social support is associated with overall QoL.

According to the results of the qualitative study in this study, overall QoL can be captured through satisfaction with the life domains such leisure, economic, and emotional domain. The literature showed that may studies have proved a key effect of satisfaction with leisure life on QOL such as overall life satisfaction [20,36]. For instance, Andereck and Nyaupane (2011) [37] indicated that opportunities for leisure activities in people’s life can increase their emotional pride and quality of life. Moreover, leisure activities can impact overall quality of life; and they pointed out that satisfaction with leisure activities can have a significant role in people’s quality of life in China, Japan, and South Korea [37].

There are a number of study findings similar to effects found in the economic domains on overall QoL. Prior studies maintained that individuals consider their economic benefits and cost in life, and this quality of life is a multi-dimensional concept, including psychological well-being, health, social resources, and economic factors. More specifically, prior studies suggested that economic level is related to people’s quality of life, and people with lower income levels reported lower quality of life [38,39]. That is, it was shown that the quality of life of those who could afford it economically was high, and it was found that income was a crucial influence. In addition, Murata et al. (2008) [39] reported that the economic element affects positive emotions and reduces negative emotions.

Past research has examined how perceptions of emotions impact on the quality of life [37,40,41]. Individuals tend to evaluate their lives positively and try to remove negative physical and environmental factors in positive emotions. These attempts can play a key role in improving self-esteem and their quality of life [41,42]. According to Ryff and Keyes (1995) [41], there is a relationship between psychological well-being and self-efficacy; those are in the extended process of behavioral intentions, positively affecting people’s quality of life [37,40]. Depending on the aims of assessing the quality of life, there have been a number of influences; the overall quality of life, however, covers leisure, economic, and emotional categories in general. Therefore, based on previous research, this current study hypothesizes the following:

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

The leisure domain is associated with overall QoL.

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

The economic domain is associated with overall QoL.

Hypothesis 5 (H5).

The emotional domain is associated with overall QoL.

Fan and Luo (2020) [43] (p. 3) mentioned that ‘psychological well-being was suggested by the eudaimonic theory of Aristotle’s school, which primarily stresses the good personal mental state and the full realization of personal potential’. This psychological well-being is generally regarded as an individual’s fulfillment and purpose in his/her efforts [40,43]. According to Baker and Kim (2020) [44], psychological well-being is dealing with a bigger concept than work satisfaction, considering employees’ overall effectiveness of their psychological functioning.

Psychological well-being is associated with an important influence on the quality of life improving an individual’s overall life [45,46]. Additionally, the psychological well-being of a laborer is related to their work performance and productivity [45,46]. Thus, people’s psychological well-being is considered to represent their emotional experience, cognitive function, and job evaluation. Prior studies mentioned that quality of life such as positive emotions, satisfaction with life and work, and the absence of negative feelings is related to psychological well-being [17,40]. Especially, the improvement in psychological well-being can be a consequence of the satisfaction of quality of life, and literature pointed out that positive emotions and satisfaction with life can reflect psychological well-being [47,48]. Those studies reveal that psychological well-being can be performed by satisfaction and happiness in which people can realize their experience in relationship to a system and social structure, and the impact of social conditions. Thus, the current study examines the direct effect of overall quality of life (QoL) on psychological well-being and hypothesizes the following.

Hypothesis 6 (H6).

Overall QoL is associated with psychological well-being.

3.2. Research Instruments

The purpose of the study is to determine the relationships amongst gig workers’ work domain, life domain, overall quality of life, and psychological well-being in order to understand and improve the employment environment of gig workers on the platform. From this point of view, this study reviewed previous studies. Then, before the research model was designed, the study intended to inspect gig workers’ psychological attitudes and aspects towards their quality of life and work environment balance through interviews. Through this process, the research model was designed. The hypothesized framework presented in Figure 1 was developed with theoretical backgrounds of quality of life. Then, the current study assessed the causality between work and life balance and the quality of life for gig workers in various aspects, and empirically analyzed their perception on the structural relationship among work and life balance and the quality of life.

The items measured in the present study have been derived from the result of the in-depth interviews from the gig workers and past studies. Work domain satisfaction was measured in two domains (working environment and social support), and for assessing life domain satisfaction, leisure, economic, and emotional constructs were measured [12,15,36]. Overall quality of life contained three items, and psychological well-being was measured based on three items [40,43]. The relevance of the questionnaire items was reviewed by professionals in the business and management sectors. Each variable was measured with multiple items using a five-point Likert scale, ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5), and 23 statements were selected to capture these constructs (Table 1).

Table 1.

Definition of constructs.

3.3. Data Collection

Academic researchers in the fields of business reviewed the initial questionnaire for unclear statements and appropriateness. Then the questionnaire was pilot tested with 50 university students to refine it, and academic specialists scrutinized the instrument for content validity. The measurement items were confirmed to refine construct reliability and validity.

An online method was adopted for the main survey to consider the survey costs and ease of use. A snowball sampling method was used. It relies on referrals from initial subjects (gig worker) to generate additional subjects [28]. The instrument was placed on the website between 26 July and 26 September 2021. In conducting the main survey, ethical issues were one of the main concerns. In this study, participation in the survey was on a voluntary basis and participants were informed about the purpose of the study before they consented to the interviews. In addition, they were told that they may withdraw from the study at any time. The raw data collected for this study were kept confidential and stored in a room which is accessible only to the principal investigator of this study.

An e-mail invitation and a link to the web-based survey were sent to participants, and explained the study’s aims. Respondents who agreed to participate in the online survey finished the self-administered questionnaire. In total, 460 questionnaires were distributed, from which 447 usable questionnaires were gained (97.2%).

Respondents provided demographic information. More than a third of the respondents (n = 188, 42.1%) were between 25 and 34 years old, and 33.6 percent (n = 150) were younger than age 25, 20.6 percent (n = 92) were between 35 and 45 years old, and 3.8 percent (n = 17) were older than age 45. Around half of respondents (56.6%) worked between 1 year and 2 years, 0.6 percent (n = 92) were under 1 year, 15.4 percent (n = 69) were between 3 and 4 years, and 7.4 percent (n = 33) were over 4 years. With regard to average level of income, a majority of the respondents (n = 163, 36.5%) earned USD 15,000–24,999 (where USD 1 = around Korean Won 1300, 8 October 2022), followed by 27.5% (n = 123) between USD 25,000 and USD 34,999, 25.1% (n = 112) between less than USD 15,000, 7.4% (n = 33) between USD 35,000 and USD 44,999, and 3.6 (n = 16) % of the respondents earned more than USD 50,000 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics of samples.

4. Findings and Discussion

4.1. Measurement Model

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was employed to investigate the adequacy of the measurement model. Past research has mentioned that, even if chi-square provides a significant p-value, the relatively large sample size (n = 447) offsets the seriousness of the influence of the statistic on the validity of the measurement model (Byrne, 2006 [49]; Hu and Bentler, 1999 [50]; Ping, 2004 [51]). Thus, multiple indices were used to ensure model fit: the comparative fit index (CFI), the goodness-of-fit index (GFI), and the adjusted and goodness-of-fit index (AGFI) were all greater than 0.9. Other indices consisted of the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) and the root mean square residual (RMR) which was less than 0.08 and generally considered a good fit [49,50].

As Table 3 provides, most of the model-fit indices from the CFA demonstrate a good fit: chi-square = 583.350, d.f. = 254, CFI = 0.958, GFI = 0.898, AGFI = 0.870, RMSEA = 0.054, and RMR = 033. The results of the CFA satisfy the recommended level of goodness-of-fit, that prior studies suggest the measurement model fits [50]. Therefore, the measurement was used to test the structural model.

Table 3.

Results of confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) for the measurement model.

Construct validity was identified by measuring convergent validity and discriminant validity [50,51]. Table 1 presents that all items load significantly on their constructs, which indicates that the measurement variables are sufficient in their representation of the constructs [44,51], and the average variance extracted (AVE) is greater than the 0.5 cut-off for all constructs. For discriminant validity, the squared correlation coefficients between any pair of constructs should be lower than the AVE for each construct [51]. As Table 2 shows all of the squared correlations between pairs of constructs are lower than the AVE for each construct. Consequently, the model is statistically acceptable and the overall measurement model describes the relationships among the eight lament constructs and the twenty-three items that measure the corresponding constructs [44,51].

4.2. Structural Analysis

The key purpose of the research is to investigate the interrelationship amongst gig workers’ work and life balance, quality of life (QoL), and psychological well-being in the service delivery platform. Thus, structural equation modeling (SEM) was performed along with the maximum likelihood method to examine relationships amongst the seven constructs in the proposed model. The overall measurement model was verified to determine the validity of the research model and Table 4 presents the estimated results of SEM.

Table 4.

Construct validity of the measurement model.

The study results confirmed a satisfactory fit with chi-square = 614.919, d.f. = 259, CFI = 0.956, GFI = 0.895, AGFI = 0.868, RMSEA = 0.056, RMR = 033. The estimation of the standardized coefficients revealed that relationships among the observed variables are statistically significant, and Table 3 shows goodness-of-fit indices of competing models. These relationships among variables were statistically significant: working environment → overall QOL (β = 0.205, p < 0.001); leisure domain → overall QOL (β = 0.196, p < 0.001); economic domain → overall QOL (β = 0.315, p < 0.001); emotional domain → overall QOL (β = 0.239, p < 0.001); and overall QOL → psychological well-being (β = 0.610, p < 0.001). However, one path is not supported (social support → overall QOL). The explained variance in the construct is 69.4 percent for ‘confirmation’, and 37.2 percent for ‘psychological well-being’ (see Table 5).

Table 5.

Construct validity of the measurement model.

According to the study results, there were statistically significant values in five paths, except for ‘social support → overall QoL’. It was found that the economic and emotional factors that belong to the life domain had more impact on the overall quality of life than the components of the ‘work category’.

This is consistent with the literature that found that the economic conditions and emotional status of service employees are related to the quality of life with statistical significance [39,52]. The literature indicated that stable income earned by labor is highly correlated to the quality of life. In particular, the literature emphasized that the economic satisfaction of workers is an important measure that ensures stability in life and security in the future, and the overall quality of life is based on the individual’s economic satisfaction [20,39,52]. Previous studies found that the psychological well-being of individuals improves their quality of life and promotes their willingness to work [20,36]. Therefore, job satisfaction is determined by the psychological and emotional status of workers, rather than the working conditions.

The results of this research confirm the results of previous studies that found that satisfaction with the working environment and leisure conditions perceived by workers positively affects their quality of life [20,43]. It was found that the economic environment and the emotional status that belong to the life category have more impact on the overall quality of life than the components of the work category. In particular, the literature indicated that instability of the work environment of employees causes stress, and deteriorates the quality of life.

This study found that the ‘overall quality of life’ is positively related to ‘psychological well-being’ with statistical significance. The ‘overall quality of life’ was measured in terms of overall satisfaction, stability in life, and work/life balance. Stability in life and satisfaction can be interpreted as the ability to concentrate on tasks with a sense of responsibility through psychological well-being. Previous studies conducted research with a focus on organizational support as a precondition for employees’ psychological well-being [20,45,46]. However, this study diversified the scope of factors affecting employees’ psychological well-being into the life category.

5. Conclusions

This study aimed to understand the employment conditions and the quality of life for gig workers, and to provide basic material regarding changes in the market and the value of the platform work. To achieve the research purpose, this study tested the relationship amongst gig workers’ work domain, life domain, overall quality of life, and psychological well-being. Most researchers on the expansion of the platform market focused on changes in labor markets and status analysis, and did not have sufficient understanding of employment insecurity, task instability, and the quality of life perceived by gig workers. The current study attempted to recognize changes in labor markets in the New Normal era and the expansion of the platform work market, and to investigate the work environment perceived by gig workers, one of the major stakeholders, from the perspective of work/life balance. This attempt will provide basic information on workers’ perspectives and awareness in order to research dealing with the platform industry.

The current study provides implications for the current status of the work environment for gig workers and the strategy to improve it. The research results will shed light on the structural relationship among work/life balance and the quality of life, and provide empirical data that allow policy makers and administrators to understand the emotional conditions of gig workers. Furthermore, a comprehensive analysis of research results will present ways for the effective operation and improvement of the gig labor market, and help understand the platform work environment, thereby providing effective policy and strategy to deal with it, and offer practical implications regarding the improvement of the employment environment for employees.

According to the research results, the fundamental solution to improve work and the quality of life perceived by gig workers is to improve the working environment and economic conditions. In particular, with the growing use of the platform in the labor market in the New Normal era, the protection of the rights of workers will emerge as an issue, due to the lack of boundaries in work, such as the lack of clear division between work and rest, and special employment status. As the literature found that employment insecurity causes task stress and the economic instability of workers and negatively impacts workers and their employers [1,7], job security can lead to healthy growth of the platform labor market and help enhance the job skills of gig workers, laying a foundation for stable employment. Hence, although discussions on legal protection and the job security of gig workers have continued, policy efforts should continue to ensure the employment security of gig workers who are not protected legally and institutionally.

Despite the implications of this study, this study has a few limitations. The present study was focused on identifying the relationships among the gig workers’ work domain, life domain, overall quality of life, and psychological well-being. However, this study did not reveal the fundamental difference in perception of quality of life considering the demographic characteristics of gig workers. Therefore, given the scarcity of research on the difference in gig worker’s perception of quality of life, further study should gain deeper insight into the difference by performing multigroup analysis for demographic profiles. In addition, platform labor is divided into ‘cloud-based smart work’ that provides labor online, and gig work that provides labor based on physical location. This study analyzed the employment environment and the quality of life for gig workers, with a focus on gig work. Subsequent studies need to cover a wider scope of gig workers, including cloud workers, and provide empirical data for more in-depth analysis of the labor markets that have emerged amid the Fourth Industrial Revolution.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.G.K.; methodology, Y.G.K. and E.W.; formal analysis, Y.K.C.; data collection, Y.K.C. and E.W.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.G.K. and E.W.; writing—review and editing, Y.K.C.; supervision and project administration, Y.G.K., Y.K.C. and E.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Jungseok Logistics Foundation.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to ethical.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Gao, P.; Wu, W.; Yang, Y. Discovering Themes and Trends in Digital Transformation and Innovation Research. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2022, 17, 1162–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, M. Rise of the Robots: Technology and the Threat of a Jobless Future; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn, K.M.; Galloway, T.L. Expanding perspectives on gig work and gig workers. J. Manag. Psychol. 2019, 34, 186–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ződi, Z.; Török, B. Constitutional Values in the Gig-Economy? Why Labor Law Fails at Platform Work, and What Can We Do about It? Societies 2021, 11, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Chaolu, T. The Impact of Offline Service Effort Strategy on Sales Mode Selection in an E-Commerce Supply Chain with Showrooming Effect. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2022, 17, 893–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Labour Office. Non-Standard Employment around the World: Understanding Challenges, Shaping Prospects; International Labour Office: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- KOSTAT. Food Industry Trends; KOSTAT: Daejeon, Republic of Korea, 2020. Available online: http://kostat.go.kr/portal/korea/kor_ko/3/4/index.board?bmode=read&aSeq=381725 (accessed on 26 September 2021).

- Churchill, B.; Craig, L. Gender in the gig economy: Men and women using digital platforms to secure work in Australia. J. Sociol. 2019, 55, 741–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzucato, M. Innovation Systems: From Fixing Market Failures to Creating Markets. Intereconomics 2015, 50, 120–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felix, R.; Garcia-Vega, J. Quality of Life in Mexico: A Formative Measurement Approach. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2012, 7, 223–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirgy, M.J. Theoretical perspectives guiding QOL indicator projects. Soc. Indic. Res. 2011, 103, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirgy, M.J.; Lee, D.-J. Macro measures of consumer well-being (CWB): A critical analysis and a research agenda. J. Macromark. 2006, 26, 27–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goods, C.; Veen, A.; Barratt, T. “Is your gig any good?” Analysing job quality in the Australian platform-based food-delivery sector. J. Ind. Relat. 2019, 61, 502–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TaJlili, M.H.; Baker, S.B. The future Work-Life-Balance attitudes scale: Assessing attitudes on work-life-balance in milliennial college women. J. Asia Pac. Couns. 2018, 8, 57–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brochard, D.; Letablier, M.-T. Trade union involvement in work–family life balance: Lessons from France. Work Employ. Soc. 2017, 31, 657–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhaus, J.H.; Collins, K.M.; Shaw, J.D. The Relation Between Work–Family Balance and Quality of Life. J. Vocat. Behav. 2003, 63, 510–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, M.; Woodcock, J. Towards a fairer platform economy: Introducing the Fairwork Foundation. Altern. Route 2018, 29, 242–253. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, E.; Moen, P.; Tranby, E. Changing workplaces to reduce work-family conflict: Schedule control in a white-collar organization. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2014, 76, 265–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kofodimos, J.R. Balancing Act; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Uysal, M.; Sirgy, M.J.; Woo, E.; Kim, H. Quality of life (QOL) and well-being research in tourism. Tour. Manag. 2016, 53, 244–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massam, B. Quality of Life: Publc Planning and Private Living. Prog. Plan. 2002, 58, 141–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shockley, K.M.; Allen, T.D. When Flexibility Helps: Another Look at the Availability of Flexible Work Arrangements and Work–Family Conflict. J. Vocat. Behav. 2007, 71, 479–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry-Smith, J.E.; Blum, T.C. Work-life human resource bundles and perceived organizational performance. Acad. Manag. J. 2000, 43, 1107–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, M.; Dhalaria, M.; Sharma, P.K.; Park, J.H. Supervised Machine-Learning Predictive Analytics for National Quality of Life Scoring. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizobuchi, M. An Iterative Multivariate Post Hoc I-Distance Approach in Evaluating OECD Better Life Index. Soc. Indic. Res. 2017, 131, 947–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, T.; Mittelhammer, R.C.; Wandschneider, P. Measuring the Quality of Life across Countries: A Sensitivity Analysis of Well-Being Indices; Working Papers; UNU-WIDER: Helsinki, Finland, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Woo, E.; Kim, H.; Uysal, M. A measure of Quality of Life in elderly tourists. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2016, 11, 65–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eves, A.; Dervisi, P. Experiences of the implementation and operation of hazard analysis critical control points in the food service sector. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2005, 24, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabeen, F.; Friesen, H.L.; Ghoudi, K. Quality of work life of Emirati women and its influence on job satisfaction and turnover intention. J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 2018, 31, 352–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, C.; Lan, J.; Li, Y.; Feng, W.; You, X. The mediating role of workplace social support on the relationship between trait emotional intelligence and teacher burnout. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2015, 51, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vangelisti, A.L. Challenges in conceptualizing social support. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 2009, 26, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palumbo, R. Let me go to the office! An investigation into the side effects of working from home on work-life balance. Int. J. Public Sect. Manag. 2020, 33, 771–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobb, S. Social support as a moderator of life stress. Psychosom. Med. 1976, 38, 300–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narehan, H.; Hairunnisa, M.; Norfadzillah, R.A.; Freziamella, L. The Effect of Quality of Work Life (QWL) Programs on Quality of Life (QOL) among Employees at Multinational Companies in Malaysia. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 112, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finch, J.F.; Graziano, W.G. Predicting depression from temperament, personality, and patterns of social relations. J. Personal. 2001, 69, 27–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Wong, M.C. Leisure and happiness: Evidence from international survey data. J. Happiness Stud. 2014, 15, 85–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andereck, K.L.; Nyaupane, G.P. Exploring the nature of tourism and quality of life perceptions among residents. J. Travel Res. 2011, 50, 248–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Yamashita, T.; Brown, J. Leisure satisfaction and quality of life in China, Japan, and South Korea: A comparative study using Asia Barometer 2006. J. Happiness Stud. 2013, 14, 753–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murata, C.; Kondo, K.; Hirai, H.; Ichida, Y.; Ojima, T. Association between depression and socio-economic status among community-dwelling elderly in Japan: The Aichi Gerontological Evaluation Study (AGES). Health Place 2008, 14, 406–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwasaki, Y.; Zuzanek, J.; Mannell, R.C. The effects of physically active leisure on stress-health relationships. Can. J. Public Health 2001, 92, 214–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C.D.; Keyes, C.L.M. The structure of psychological well-being revisited. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1995, 69, 719–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worsch, C.; Schier, M.F. Personality and quality of life: The importance of optimism and goal adjustment. Qual. Life Res. 2002, 12, 59–72. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, Y.; Luo, J. Impact of generativity on museum visitors’ engagement, experience, and psychological well-being. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 42, 100958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, M.A.; Kim, K. Dealing with customer incivility: The effects of managerial support on employee psychological well-being and quality-of-life. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 87, 102503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobreros, C.; Medoza-Ruvalcaba, N.; Flores-García, M.; Roggema, R. Improving Psychological Well-Being in Urban University Districts through Biophilic Design: Two Cases in Mexico. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randall, K.; Ford, T.G.; Kwon, K.-A.; Sisson, S.S.; Bice, M.R.; Dinkel, D.; Tsotsoros, J. Physical Activity, Physical Well-Being, and Psychological Well-Being: Associations with Life Satisfaction during the COVID-19 Pandemic among Early Childhood Educators. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooke, P.; Melchert, T.; Connor, K. Measuring well-being: A review of instruments. Couns. Psychol. 2016, 44, 730–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothrauff, T.; Cooney, T.M. The role of generativity in psychological wellbeing: Does it differ for childless adults and parents? J. Adult Dev. 2008, 15, 148–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B. Structural Equation Modeling with EQS: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ping, R. On assuring valid measures for theoretical models using survey data. J. Bus. Res. 2004, 57, 125–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell-Sills, L.; Barlow, D.H.; Brown, T.A.; Hofmann, S.G. Acceptability and suppression of negative emotion in anxiety and mood disorders. Emotion 2006, 6, 587–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).