Environmental and Social Performance of the Banking Industry in Bangladesh: Effect of Stakeholders’ Pressure and Green Practice Adoption

Abstract

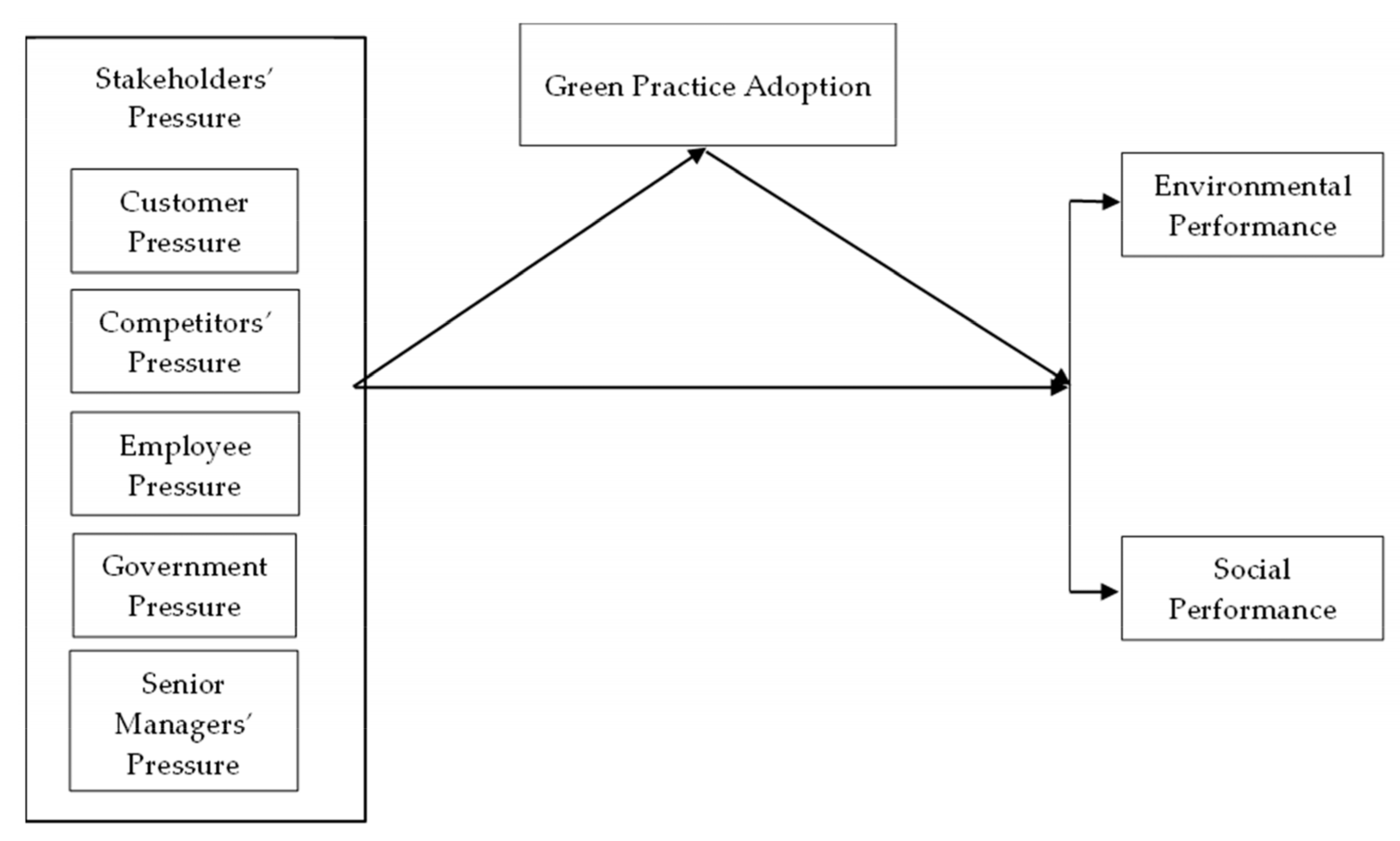

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Stakeholder Theory (ST)

2.2. Sustainability Performance

2.3. Environmental Performance

2.4. Social Performance

2.5. Stakeholders’ Pressure and Environmental Performance

2.6. Stakeholders’ Pressure and Corporate Social Performance

2.7. Stakeholders’ Pressure and Green Practice Adoption

2.8. Green Practice Adoption and Environmental and Social Performance

2.9. Green Practice Adoption (GPA) as a Mediator

3. Methodology

3.1. Survey Measures

3.2. Data Analysis

4. Data Analysis and Results

4.1. Hierarchical Model of Stakeholders’ Pressure

4.2. Measurement Model

4.3. Structural Model

5. Discussions and Conclusions

5.1. Discussions of the Research

5.2. Theoretical Implications

5.3. Practical Implications

6. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Constructs | Measurement Items | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Customers’ Pressure Zhang & Yang (2016) [120] | Our customers have established an effective environmental management system. | Rasi et al. (2014) [139] Singh et al. (2015) [140] Zhang et al. (2020) [141] Chu et al. (2019) [142] |

| Customers pay great attention to searching for suppliers with environmental responsibility and green awareness. | ||

| Customers require our products to meet their green requirements and are eager to pay more for green products. | ||

| Customers will monitor our service process and visit our firm regularly. | ||

| Express companies feel pressure from customers to provide green services. | ||

| Customers pay more attention to the environmental protection of operational processes. | ||

| Customers require us to improve environmental performance. | ||

| If the company does not meet the environmental requirements of customers, they will terminate the contract. | ||

| Governments’ Pressure/Regulatory Pressure Zhang & Yang (2016) [92] | Our firm properly implemented national and local environmental regulations (such as cleaner production). | Qi et al. (2010) [93] Zhu et al. (2013) [143] Rasi et al. (2014) [139] Zhang et al. (2020) [141] |

| Governments provide preferential subsidy and tax policy on green practices. | ||

| The company has restricted loans to the firms that have a tendency for environmental accidents. | ||

| Government provides financial support for adopting green practices. | ||

| Government provides technical assistance for adopting green practices. | ||

| Government helps with training manpower on green logistics skills. | ||

| Employees’ Pressure Zhang & Yang (2016) [92] | Employee put pressure on the bank to improve their working environment. | Eiadat et al. (2008) [144] Zhu et al. (2013) [143] Zhang & Yang (2016) [92] |

| Employees have a strong desire to improve their working environment and reduce potential health threats. | ||

| Employees know well about the pollution and toxic materials generated in the banking services process. | ||

| Employees know well that the bank makes environmental pollution. | ||

| Employees have the autonomy to make environmental decisions (green empowerment). | ||

| Bottom-up employees put pressure on senior employees to provide loans for green projects. | ||

| Senior Managers’ Pressure Zhang & Yang (2016) [92] | Our firm assesses senior managers’ contributions to the advancement of environmental performance. | Eiadat et al. (2008) [144] Qi et al. (2010) [93] |

| Senior managers in our firm have a higher environmental commitment and awareness. | ||

| Senior managers have a positive attitude toward green practices. | ||

| Environmental initiatives will receive support from senior managers. | ||

| Competitors’ Pressure Zhang & Yang (2016) [92] | Competitors can achieve competitive advantage through higher environmental awareness. | Qi et al. 2010 [115] Rasi et al. (2014) [110] Singh et al. (2015) [111] |

| Competitors employ green strategy to enter and occupy new high-profit markets. | ||

| Competitors try to enlarge their market share by green practices adoption. | ||

| Competitors can establish a better environmental image through green practices. | ||

| Green Practices Zhang & Yang (2016) [92] | My company substitutes greener materials/parts in place of polluting and hazardous materials/parts. | Suganthi (2019) [28] |

| My company designs products (loans) that are focused on reducing resource consumption/waste generation during production and distribution to the end-of-loan users. | ||

| We influence employees to reduce resource consumption and use renewable energy while providing services. | ||

| Our bank checks environmental criteria during supplier selection. | ||

| Our clients generate small amounts of waste during production. | ||

| Our bank has established Green auditing systems. | ||

| Our bank provides training about green management to the employees. | ||

| Bank employees understand and recognize environmental problems. | ||

| A separate department works to remove the environmental problems that negatively affect banking activities. | ||

| Environmental Performance | My company has defined environmental policies. | Zaid et al. (2020) [145] Zhu et al. (2013) [143] Li (2014) [146] Jabbour et al. (2015) [147] |

| Our firm has taken initiative to conserve natural resources. | ||

| The bank provides loans to firms that recycle waste products. | ||

| Our organization has improved the company’s environmental reputation and image in the market. | ||

| Our firm designed a loan in order to reduce toxic gas emission/solid wastes/wastewater and hazardous and harmful materials. | ||

| Our firm has taken initiatives for reduction of Climate change. | ||

| Our company has designed a policy to reduce energy/fuel usage. | Sajan et al. (2017) [148] Abdul-Rashid et al. (2017) [149] | |

| Our firm has conducted regular environmental audits. | ||

| Social performance | My company has donated money as part of CSR for improving the quality of living of the surrounding community. | Wang and Dai (2018) [150] Abdul-Rashid et al. (2017) [121] |

| My company has designed a policy for improving workers’ occupational health and safety. | ||

| My company is committed to improving job satisfaction levels of employees. | ||

| We donated money for improving relationships with the community and stakeholders. |

References

- Drazkiewicz, A.; Challies, E.; Newig, J. Public Participation and Local Environmental Planning: Testing Factors Influencing Decision Quality and Implementation in Four Case Studies from Germany. Land Use Policy 2015, 46, 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Khan, M.A.S.; Anwar, F.; Shahzad, F.; Adu, D.; Murad, M. Green Innovation Practices and Its Impacts on Environmental and Organizational Performance. Front. Psychol. 2021, 11, 553625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prakash, A.; Potoski, M. Racing to the Bottom? Trade, Environmental Governance, and ISO 14001. Am. J. Pol. Sci. 2006, 50, 350–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camilleri, M.A. The Rationale for ISO 14001 Certification: A Systematic Review and a Cost–Benefit Analysis. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2022, 29, 1067–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, G.Y.; Zeng, S.X.; Tam, C.M.; Yin, H.T.; Wu, J.F.; Dai, Z.H. Diffusion of ISO 14001 Environmental Management Systems in China: Rethinking on Stakeholders’ Roles. J. Clean. Prod. 2011, 19, 1250–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacheco, L.; Lobo, C.; Maldonado, I. Do ISO Certifications Enhance Internationalization? The Case of Portuguese Industrial SMEs. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranganathan, J. Sustainability Rulers: Measuring Corporate Environmental and Social Performance. In Sustainability Enterprise Perspective; World Resources Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 1998; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Darnall, N.; Edwards, D. Predicting the Cost of Environmental Management System Adoption: The Role of Capabilities, Resources and Ownership Structure. Strateg. Manag. J. 2006, 27, 301–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalabik, B.; Fairchild, R.J. Customer, Regulatory, and Competitive Pressure as Drivers of Environmental Innovation. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2011, 131, 519–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fijałkowska, J.; Zyznarska-Dworczak, B.; Garsztka, P. Corporate Social-Environmental Performance versus Financial Performance of Banks in Central and Eastern European Countries. Sustainability 2018, 10, 772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madsen, H.; Ulhøi, J.P. Integrating Environmental and Stakeholder Management. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2001, 10, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutantoputra, A. Do Stakeholders’ Demands Matter in Environmental Disclosure Practices? Evidence from Australia. J. Manag. Gov. 2022, 26, 449–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Anbumozhi, V. Determinant Factors of Corporate Environmental Information Disclosure: An Empirical Study of Chinese Listed Companies. J. Clean. Prod. 2009, 17, 593–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baah, C.; Opoku-Agyeman, D.; Acquah, I.S.K.; Agyabeng-Mensah, Y.; Afum, E.; Faibil, D.; Abdoulaye, F.A.M. Examining the Correlations between Stakeholder Pressures, Green Production Practices, Firm Reputation, Environmental and Financial Performance: Evidence from Manufacturing SMEs. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 27, 100–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werther, W.B., Jr.; Chandler, D. Strategic Corporate Social Responsibility: Stakeholders in a Global Environment No Title, 2nd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2010; ISBN 978-1-4129-7453-0. [Google Scholar]

- Shahzad, M.; Qu, Y.; Zafar, A.U.; Ding, X.; Rehman, S.U. Translating Stakeholders’ Pressure into Environmental Practices—The Mediating Role of Knowledge Management. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 275, 124163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemens, B.; Douglas, T.J. Does Coercion Drive Firms to Adopt “voluntary” Green Initiatives? Relationships among Coercion, Superior Firm Resources, and Voluntary Green Initiatives. J. Bus. Res. 2006, 59, 483–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadi, S.; OmSalameh Pourhashemi, S.; Nilashi, M.; Abdullah, R.; Samad, S.; Yadegaridehkordi, E.; Aljojo, N.; Razali, N.S. Investigating Influence of Green Innovation on Sustainability Performance: A Case on Malaysian Hotel Industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 258, 120860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baah, C.; Jin, Z.; Tang, L. Organizational and Regulatory Stakeholder Pressures Friends or Foes to Green Logistics Practices and Financial Performance: Investigating Corporate Reputation as a Missing Link. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 247, 119125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baah, C.; Opoku-Agyeman, D.; Acquah, I.S.K.; Issau, K.; Moro Abdoulaye, F.A. Understanding the Influence of Environmental Production Practices on Firm Performance: A Proactive versus Reactive Approach. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2020, 32, 266–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.W.; Kim, Y.M.; Kim, Y.E. Antecedents of Adopting Corporate Environmental Responsibility and Green Practices. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 148, 397–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.Y.; Ho, Y.H. Determinants of Green Practice Adoption for Logistics Companies in China. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 98, 67–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, Y.; Wu, W. How Does Green Innovation Improve Enterprises’ Competitive Advantage? The Role of Organizational Learning. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 26, 504–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, T.; Feng, T.; Ye, C. Advanced Manufacturing Technologies and Green Innovation: The Role of Internal Environmental Collaboration. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Yang, M.X.; Zeng, K.J.; Feng, W. Green Knowledge Sharing, Stakeholder Pressure, Absorptive Capacity, and Green Innovation: Evidence from Chinese Manufacturing Firms. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 1517–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bose, S.; Khan, H.Z.; Rashid, A.; Islam, S. What Drives Green Banking Disclosure? An Institutional and Corporate Governance Perspective. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2018, 35, 501–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Ramanathan, R. An Empirical Examination of Stakeholder Pressures, Green Operations Practices and Environmental Performance. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2015, 53, 6390–6407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suganthi, L. Examining the Relationship between Corporate Social Responsibility, Performance, Employees’ pro-Environmental Behavior at Work with Green Practices as Mediator. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 232, 739–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riva, F.; Magrizos, S.; Rubel, M.R.B. Investigating the Link between Managers’ Green Knowledge and Leadership Style, and Their Firms’ Environmental Performance: The Mediation Role of Green Creativity. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2021, 30, 3228–3240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-S.; Chang, T.-W.; Lin, C.-Y.; Lai, P.-Y.; Wang, K.-H. The Influence of Proactive Green Innovation and Reactive Green Innovation on Green Product Development Performance: The Mediation Role of Green Creativity. Sustainability 2016, 8, 966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indriastuti, M.; Chariri, A. The Role of Green Investment and Corporate Social Responsibility Investment on Sustainable Performance. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2021, 8, 1960120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alt, E.; Díez-de-Castro, E.P.; Lloréns-Montes, F.J. Linking Employee Stakeholders to Environmental Performance: The Role of Proactive Environmental Strategies and Shared Vision. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 128, 167–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.T.; Raschke, R.L. Stakeholder Legitimacy in Firm Greening and Financial Performance: What about Greenwashing Temptations? J. Bus. Res. 2023, 155, 113393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bıçakcıoğlu-Peynirci, N.; Tanyeri, M. Stakeholder and Resource-based Antecedents and Performance Outcomes of Green Export Business Strategy: Insights from an Emerging Economy. Int. J. Emerg. Mark. 2022, 17, 1–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adomako, S.; Tran, M.D. Stakeholder Management, CSR Commitment, Corporate Social Performance: The Moderating Role of Uncertainty in CSR Regulation. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2022, 29, 1414–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seroka-Stolka, O.; Fijorek, K. Linking Stakeholder Pressure and Corporate Environmental Competitiveness: The Moderating Effect of ISO 14001 Adoption. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2022, 29, 1663–1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yawar, S.A.; Seuring, S. Management of Social Issues in Supply Chains: A Literature Review Exploring Social Issues, Actions and Performance Outcomes. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 141, 621–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Souza, C.; Ahmed, T.; Khashru, M.A.; Ahmed, R.; Ratten, V.; Jayaratne, M. The Complexity of Stakeholder Pressures and Their Influence on Social and Environmental Responsibilities. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 358, 132038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Pitman Publishing: Boston, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Helmig, B.; Spraul, K.; Ingenhoff, D. Under Positive Pressure: How Stakeholder Pressure Affects Corporate Social Responsibility Implementation. Bus. Soc. 2016, 55, 151–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Li, W.; Qi, L. Stakeholder Pressures and Corporate Environmental Strategies: A Meta-Analysis. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shubham; Charan, P.; Murty, L.S. Secondary Stakeholder Pressures and Organizational Adoption of Sustainable Operations Practices: The Mediating Role of Primary Stakeholders. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2018, 27, 910–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonamigo, A.; Dettmann, B.; Frech, C.G.; Werner, S.M. Facilitators and Inhibitors of Value Co-Creation in the Industrial Services Environment. J. Serv. Theory Pract. 2020, 30, 609–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkis, J.; Gonzalez-Torre, P.; Adenso-Diaz, B. Stakeholder Pressure and the Adoption of Environmental Practices: The Mediating Effect of Training. J. Oper. Manag. 2010, 28, 163–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatoglu, E.; Bayraktar, E.; Arda, O.A. Adoption of Corporate Environmental Policies in Turkey. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 91, 313–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hristov, I.; Appolloni, A.; Cheng, W.; Huisingh, D. Aligning Corporate Social Responsibility Practices with the Environmental Performance Management Systems: A Critical Review of the Relevant Literature. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2022, 33, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hristov, I.; Chirico, A. The Cultural Dimension as a Key Value Driver of the Sustainable Development at a Strategic Level: An Integrated Five-Dimensional Approach. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2022, 24, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteban-Sanchez, P.; de la Cuesta-Gonzalez, M.; Paredes-Gazquez, J.D. Corporate Social Performance and Its Relation with Corporate Financial Performance: International Evidence in the Banking Industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 162, 1102–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hristov, I.; Appolloni, A. Stakeholders’ Engagement in the Business Strategy as a Key Driver to Increase Companies’ Performance: Evidence from Managerial and Stakeholders’ Practices. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2022, 31, 1488–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisi, I.E. Determinants and Performance Effects of Social Performance Measurement Systems. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 152, 225–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, T.M.; Wicks, A.C. Convergent Stakeholder Theory. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1999, 24, 206–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laplume, A.O.; Sonpar, K.; Litz, R.A. Stakeholder Theory: Reviewing a Theory That Moves Us. J. Manag. 2008, 34, 1152–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, T.; Preston, L.E. The Stakeholder Theory of the Corporation: Concepts, Evidence, and Implications. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 65–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langtry, B. Stakeholders and the Moral Responsibilities of Business. Bus. Ethics Q. 1994, 4, 431–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, P.; Roth, K. Why Companies Go Green: Responsiveness. Acad. Manag. 2000, 43, 717–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neu, D.; Warsame, H.; Pedwell, K. Managing Public Impressions: Environmental Disclosures in Annual Reports. Account. Organ. Soc. 1998, 23, 265–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buysse, K.; Verbeke, A. Proactive Environmental Strategies: A Stakeholder Management Perspective. Strateg. Manag. J. 2003, 24, 453–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkis, J.; Zhu, Q.; Lai, K.H. An Organizational Theoretic Review of Green Supply Chain Management Literature. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2011, 130, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, A.; Schröder, M.; Rennings, K. The Effect of Environmental and Social Performance on the Stock Performance of European Corporations. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2007, 37, 661–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahoney, L.; Roberts, R.W. Corporate Social and Environmental Performance and Their Relation to Financial Performance and Institutional Ownership: Empirical Evidence on Canadian Firms. Account. Forum 2007, 31, 233–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.-J.; Wang, H.-J.; Chang, C.-P. Environmental Performance, Green Finance and Green Innovation: What’s the Long-Run Relationships among Variables? Energy Econ. 2022, 110, 106004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asiaei, K.; Bontis, N.; Alizadeh, R.; Yaghoubi, M. Green Intellectual Capital and Environmental Management Accounting: Natural Resource Orchestration in Favor of Environmental Performance. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2022, 31, 76–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavez, R.; Yu, W.; Jajja, M.S.S.; Song, Y.; Nakara, W. The Relationship between Internal Lean Practices and Sustainable Performance: Exploring the Mediating Role of Social Performance. Prod. Plan. Control 2022, 33, 1025–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.-H.; Ong, C.-F.; Hsu, S.-C. The Linkages between Internationalization and Environmental Strategies of Multinational Construction Firms. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 116, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolk, A.; Fortanier, F. Internationalization and Environmental Disclosure: The Role of Home and Host Institutions. Multinatl. Bus. Rev. 2013, 21, 87–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.P.; Adomako, S. International Orientation and Environmental Performance in Vietnamese Exporting Small- and Medium-sized Enterprises. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2022, 31, 2424–2436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Wang, L. Environmental Entrepreneurial Orientation and Firm Performance: The Role of Environmental Innovation and Stakeholder Pressure. SAGE Open 2022, 12, 215824402110613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turban, D.B.; Greening, D.W. Corporate Social Performance And Organizational Attractiveness To Prospective Employees. Acad. Manag. J. 1997, 40, 658–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anser, M.K.; Yousaf, Z.; Majid, A.; Yasir, M. Does Corporate Social Responsibility Commitment and Participation Predict Environmental and Social Performance? Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 2578–2587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, F.N.; Wang, H.-M.D.; Ho-Dac, N.; Vitell, S.J. Nature and Relationship between Corporate Social Performance and Firm Size: A Cross-National Study. Soc. Responsib. J. 2019, 15, 258–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.Y.; Lee, C. Managerial Efficiency, Corporate Social Performance, and Corporate Financial Performance. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 158, 467–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardberg, N.A.; Zyglidopoulos, S.C.; Symeou, P.C.; Schepers, D.H. The Impact of Corporate Philanthropy on Reputation for Corporate Social Performance. Bus. Soc. 2019, 58, 1177–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, S. The Influence of External and Internal Stakeholder Pressures on the Implementation of Upstream Environmental Supply Chain Practices. Bus. Soc. 2020, 59, 351–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, A.; Ullah, I.; Afridi, F.e.A.; Ullah, Z.; Zeeshan, M.; Hussain, A.; Rahman, H.U. Adoption of Green Banking Practices and Environmental Performance in Pakistan: A Demonstration of Structural Equation Modelling. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 23, 13200–13220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rui, Z.; Lu, Y. Stakeholder Pressure, Corporate Environmental Ethics and Green Innovation. Asian J. Technol. Innov. 2021, 29, 70–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Zhu, L. Enhancing Corporate Sustainable Development: Stakeholder Pressures, Organizational Learning, and Green Innovation. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2019, 28, 1012–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Rosati, F.; Chai, H.; Feng, T. Market Orientation Practices Enhancing Corporate Environmental Performance via Knowledge Creation: Does Environmental Management System Implementation Matter? Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 1899–1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmas, M.A.; Toffel, M.W. Organizational Responses to Environmental Demands: Opening the Black Box. Strateg. Manag. J. 2008, 29, 1027–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frooman, J. Stakeholder Influence Strategies. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1999, 24, 191–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melander, L. Success Factors for Environmentally Sustainable Product Innovation; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; ISBN 9780128173824. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Q.; Sarkis, J. The Moderating Effects of Institutional Pressures on Emergent Green Supply Chain Practices and Performance. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2007, 45, 4333–4355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rugman, A.M.; Verbeke, A. Corporate Strategies and Environmental Regulations: An Organizing Framework. Bus. Ethics Strategy Vol. I II 2018, 19, 291–303. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Q.; Sarkis, J. Relationships between Operational Practices and Performance among Early Adopters of Green Supply Chain Management Practices in Chinese Manufacturing Enterprises. J. Oper. Manag. 2004, 22, 265–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.K.; Lujan-Blanco, I.; Fortuny-Santos, J.; Ruiz-De-arbulo-lópez, P. Lean Manufacturing and Environmental Sustainability: The Effects of Employee Involvement, Stakeholder Pressure and Iso 14001. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaggi, B.; Zhao, R. Environmental Performance and Reporting: Perceptions of Managers and Accounting Professionals in Hong Kong. Int. J. Account. 1996, 31, 333–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, J. Impact of Total Quality Management on Corporate Green Performance through the Mediating Role of Corporate Social Responsibility. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 242, 118458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.C.; Tan, K.C.; Zailani, S.H.M.; Jayaraman, V. Supply Chain Drivers That Foster the Development of Green Initiatives in an Emerging Economy. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2013, 33, 656–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassinis, G.; Vafeas, N. Stakeholder Pressures and Environmental Performance. Acad. Manag. J. 2006, 49, 145–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, M.J.; Buhovac, A.R.; Yuthas, K. Managing Social, Environmental and Financial Performance Simultaneously. Long Range Plan. 2015, 48, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-M.; Delmas, M. Measuring Corporate Social Performance: An Efficiency Perspective. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2011, 20, 789–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halme, M.; Rintamäki, J.; Knudsen, J.S.; Lankoski, L.; Kuisma, M. When Is There a Sustainability Case for CSR? Pathways to Environmental and Social Performance Improvements. Bus. Soc. 2020, 59, 1181–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, G.Y.; Shen, L.Y.; Zeng, S.X.; Jorge, O.J. The Drivers for Contractors’ Green Innovation: An Industry Perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2010, 18, 1358–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilyas, S.; Hu, Z.; Wiwattanakornwong, K. Unleashing the Role of Top Management and Government Support in Green Supply Chain Management and Sustainable Development Goals. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 8210–8223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miroshnychenko, I.; Barontini, R.; Testa, F. Green Practices and Financial Performance: A Global Outlook. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 147, 340–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stekelorum, R.; Laguir, I.; Gupta, S.; Kumar, S. Green Supply Chain Management Practices and Third-Party Logistics Providers’ Performances: A Fuzzy-Set Approach. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2021, 235, 108093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahl, S. The Role of Green Banking in Sustainable Growth. Int. J. Mark. Financ. Serv. Manag. Res. 2012, 1, 27–35. [Google Scholar]

- Meena, R. Green Banking: As Initiative for Sustainable Development. Glob. J. Manag. Bus. Stud. 2013, 3, 1181–1186. [Google Scholar]

- Joshi, V. A Study of Social and Ethical Issues in Banking Industry. Int. J. Econ. Res. 2011, 2, 49–57. [Google Scholar]

- He, W.; Liu, P.; Lin, B.; Zhou, H.; Chen, X. Green Finance Support for Development of Green Buildings in China: Effect, Mechanism, and Policy Implications. Energy Policy 2022, 165, 112973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Sarkis, J.; Geng, Y. Green Supply Chain Management in China: Pressures, Practices and Performance. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2005, 25, 449–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giunipero, L.C.; Hooker, R.E.; Denslow, D. Purchasing and Supply Management Sustainability: Drivers and Barriers. J. Purch. Supply Manag. 2012, 18, 258–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, H.; Lannelongue, G.; Gonzalez-Benito, J. Integrating Green Practices into Operational Performance: Evidence from Brazilian Manufacturers. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, R.; Gunasekaran, A.; Samar Ali, S. Exploring the Relationship between Leadership, Operational Practices, Institutional Pressures and Environmental Performance: A Framework for Green Supply Chain. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2015, 160, 120–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, M.; Qu, Y.; Zafar, A.U.; Rehman, S.U.; Islam, T. Exploring the Influence of Knowledge Management Process on Corporate Sustainable Performance through Green Innovation. J. Knowl. Manag. 2020, 24, 2079–2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.T. The Effect of Green Supply Chain Management Practices on Sustainability Performance in Vietnamese Construction Materials Manufacturing Enterprises. Uncertain Supply Chain Manag. 2020, 8, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, J.Y.; Yusliza, M.-Y.; Ramayah, T.; Fawehinmi, O. Nexus between Green Intellectual Capital and Green Human Resource Management. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 215, 364–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acquah, I.S.K.; Essel, D.; Baah, C.; Agyabeng-Mensah, Y.; Afum, E. Investigating the Efficacy of Isomorphic Pressures on the Adoption of Green Manufacturing Practices and Its Influence on Organizational Legitimacy and Financial Performance. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2021, 32, 1399–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, B.; Cao, X. Do Corporate Social Responsibility Practices Contribute to Green Innovation? The Mediating Role of Green Dynamic Capability. Technol. Soc. 2022, 68, 101868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, S.S. The Ethics of ‘Going Green’: The Corporate Social Responsibility Debate. Bus. Strategy Environ. 1999, 8, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohas, A.; Poussing, N. An Empirical Exploration of the Role of Strategic and Responsive Corporate Social Responsibility in the Adoption of Different Green IT Strategies. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 122, 240–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Ren, S.; Yu, J. Bridging the Gap between Corporate Social Responsibility and New Green Product Success: The Role of Green Organizational Identity. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2019, 28, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagoudis, I.N.; Shakri, A.R. A Framework for Measuring Carbon Emissions for Inbound Transportation and Distribution Networks. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2015, 17, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, S.; Rehman, S.U.; García, F.J.S. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Performance: The Mediating Role of Environmental Strategy and Green Innovation. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2020, 160, 120262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubel, M.R.B.; Kee, D.M.H.; Rimi, N.N. Green Human Resource Management and Supervisor Pro-Environmental Behavior: The Role of Green Work Climate Perceptions. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 313, 127669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumberg, B.; Cooper, D.; Schindler, P. Business Research Methods, 4th ed.; McGraw-Hill Education: Berkshire, UK, 2014; ISBN 100077157486. [Google Scholar]

- Rubel, M.R.B.; Kee, D.M.H.; Rimi, N.N.; Yusoff, Y.M. Adapting Technology: Effect of High-Involvement HRM and Organisational Trust. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2017, 36, 281–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.; Arshad, M.A.; Mahmood, A.; Akhtar, S. The Influence of Spiritual Values on Employee’s Helping Behavior: The Moderating Role of Islamic Work Ethic. J. Manag. Spiritual. Relig. 2019, 16, 235–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubel, M.R.B.; Hung Kee, D.M.; Rimi, N.N. High-Performance Work Practices and Medical Professionals’ Work Outcomes: The Mediating Effect of Perceived Organizational Support. J. Adv. Manag. Res. 2020, 18, 368–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Yang, F. On the Drivers and Performance Outcomes of Green Practices Adoption An Empirical Study in China. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2016, 116, 2011–2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bissing-Olson, M.J.; Iyer, A.; Fielding, K.S.; Zacher, H. Relationships between Daily Affect and Pro-Environmental Behavior at Work: The Moderating Role of pro-Environmental Attitude. J. Organ. Behav. 2013, 34, 156–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, S.K.S. Environmental Requirements, Knowledge Sharing and Green Innovation: Empirical Evidence from the Electronics Industry in China. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2013, 22, 321–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to Use and How to Report the Results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common Method Biases in Behavioral Research: A Critical Review of the Literature and Recommended Remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W. How to Write up and Report PLS Analyses. In Handbook of Partial Least Squares: Concepts, Methods and Applications; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; pp. 655–690. [Google Scholar]

- Hulland, J. Use of Partial Least Squares (PLS) in Strategic Management Research: A Review of Four Recent Studies. Strateg. Manag. J. 1999, 20, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A New Criterion for Assessing Discriminant Validity in Variance-Based Structural Equation Modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S. Psychosocial Models of the Role of Social Support in the Etiology of Physical Disease. Health Psychol. 1988, 7, 269–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and Resampling Strategies for Assessing and Comparing Indirect Effects in Multiple Mediator Models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mensah, I. Stakeholder Pressure and Hotel Environmental Performance in Accra, Ghana. Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2014, 25, 227–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elijido-Ten, E. Applying Stakeholder Theory to Analyze Corporate Environmental Performance: Evidence from Australian Listed Companies. Asian Rev. Account. 2007, 15, 164–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J.B.; Harrison, J.S. Stakeholder Theory at the Crossroads. Bus. Soc. 2020, 59, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güney, T. Environmental Sustainability and Pressure Groups. Qual. Quant. 2015, 49, 2331–2344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.-D.P. Configuration of External Influences: The Combined Effects of Institutions and Stakeholders on Corporate Social Responsibility Strategies. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 102, 281–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, H.H.R.; Chen, J.S.; Chen, P.C. Effects of Green Innovation on Environmental and Corporate Performance: A Stakeholder Perspective. Sustainability 2015, 7, 4997–5026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Wang, G.Z.; Ma, X. Environmental Innovation Practices and Green Product Innovation Performance: A Perspective from Organizational Climate. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 28, 224–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojo, A.O.; Fauzi, M.A. Environmental Awareness and Leadership Commitment as Determinants of IT Professionals Engagement in Green IT Practices for Environmental Performance. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2020, 24, 298–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaksar, E.; Abbasnejad, T.; Esmaeili, A.; Tamošaitienė, J. The Effect of Green Supply Chain Management Practices on Environmental Performance and Competitive Advantage: A Case Study of the Cement Industry. Technol. Econ. Dev. Econ. 2016, 22, 293–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuraidah Raja Mohd Rasi, R.; Abdekhodaee, A.; Nagarajah, R. Stakeholders’ Involvements in the Implementation of Proactive Environmental Practices. Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2014, 25, 132–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Jain, S.; Sharma, P. Motivations for Implementing Environmental Management Practices in Indian Industries. Ecol. Econ. 2015, 109, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; He, J.; Shi, X.; Hong, Q.; Bao, J.; Xue, S. Technology Characteristics, Stakeholder Pressure, Social Influence, and Green Innovation: Empirical Evidence from Chinese Express Companies. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, Z.; Wang, L.; Lai, F. Customer Pressure and Green Innovations at Third Party Logistics Providers in China The Moderation Effect of Organizational Culture. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2019, 30, 57–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Sarkis, J.; Lai, K. Institutional-Based Antecedents and Performance Outcomes of Internal and External Green Supply Chain Management Practices. J. Purch. Supply Manag. 2013, 19, 106–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eiadat, Y.; Kelly, A.; Roche, F.; Eyadat, H. Green and Competitive? An Empirical Test of the Mediating Role of Environmental Innovation Strategy. J. World Bus. 2008, 43, 131–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaid, M.A.A.; Wang, M.; Adib, M.; Sahyouni, A.; Abuhijleh, S.T. Boardroom Nationality and Gender Diversity: Implications for Corporate Sustainability Performance. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 251, 119652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y. Environmental Innovation Practices and Performance: Moderating Effect of Resource Commitment. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 66, 450–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbour, C.J.C.; Jugend, D.; Jabbour, A.B.L.d.S.; Gunasekaran, A.; Latan, H. Green Product Development and Performance of Brazilian Firms: Measuring the Role of Human and Technical Aspects. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 87, 442–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajan, M.P.; Shalij, P.R.; Ramesh, A. Lean Manufacturing Practices in Indian Manufacturing SMEs and Their Effect on Sustainability Performance. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2017, 28, 772–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul-Rashid, S.H.; Sakundarini, N.; Ghazilla, R.A.R.; Thurasamy, R. The Impact of Sustainable Manufacturing Practices on Sustainability Performance: Empirical Evidence from Malaysia. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2017, 37, 182–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Dai, J. Sustainable Supply Chain Management Practices and Performance. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2018, 118, 2–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Authors (Year) | Focus | Sample | Relevant Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alt et al. (2015) [32] | Environmental performance | Survey questionnaire to 1921 firms | Proactive environmental strategies (PES) were positively and significantly connected to employee stakeholder integration, and PES were positively and significantly related to environmental performance. This relationship was prominent for high levels of shared vision. |

| Helmig et al. (2016) [40] | Corporate Social Responsibility | survey questionnaire to 1000 top managers | Primary stakeholders Pressure increases CSR implementation. |

| Baah et al. (2020) [19] | Green production practices and environmental performance | Data collection through email (226 questionnaires from SME) | Pressures from organizational stakeholders had a favorable and significant impact on the adoption of green manufacturing techniques, the standing of the company, and environmental performance. |

| Graham (2020) [74] | Environmental Supply Chain Practices | 149 manufacturing companies | Competitive pressure and proactive strategy have separate and combined effects on supply chain environmental practices. |

| Rehman et al. (2020) [75] | Green banking and environmental performance | Survey questionnaire 200 | The effect of green practices has been documented to be much greater and significant in stimulating green environment. |

| Rui & Lu (2020) [76] | Environmental ethics and green innovation | Survey 278 enterprises | Stakeholder pressure can support green innovation and corporate environmental ethics. |

| Shahzad et al. (2020) [16] | Environmental practices | Survey from 318 respondents of the manufacturing industries of Pakistan | Stakeholder pressure significantly improves green innovation, CSR, and knowledge management processes. |

| Sutantoputra (2020) [12] | Environmental disclosure | Case study (9 companies have taken) | Stakeholders (customers, investors) influence more environmental disclosure. |

| Khuong et al. (2021) [49] | Stakeholders and Corporate Social Responsibility | Surveys of 869 leaders and managers | Stakeholder influence has a favorable impact on business reputation in addition to having a big impact on CSR kinds. |

| Rhee et al. (2021) [51] | Stakeholder Pressures on Strategic CSR Activities | Survey data of 177 Korean foreign subsidiaries | Secondary stakeholders have a greater impact on strategic CSR initiatives than on reactive ones. |

| Bıçakcıoğlu-Peynirci & Tanyeri (2022) [34] | Green export business strategy’s results | 235 questionnaires were collected from exporting manufacturing companies | The organizational competencies, stakeholder demands, and resources all significantly affect the green export business plan. |

| D’Souza et al. (2022) [38] | Social and environmental responsibilities | Face-to-face interviews (286 from social businesses) | Primary stakeholders and secondary stakeholders have a significant impact on social responsibility. Secondary stakeholders were found to have a considerable influence on environmental responsibility, even when primary stakeholders had an indirect influence. |

| (CR = 0.891, AVE = 0.621) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Customer Pressure | Competitors’ Pressure | Employee Pressure | Government Pressure | Senior Managers’ Pressure |

| R2 = 0.451 | R2 = 0.639 | R2 = 0.621 | R2 = 0.745 | R2 = 0.650 |

| β = 0.672 | β = 0.799 | β = 0.788 | β = 0.863 | β = 0.806 |

| p < 0.01 | p < 0.01 | p < 0.01 | p < 0.01 | p < 0.01 |

| Constructs | Items | FL | AVE | CR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Customer Pressure (CP) | CP1 | 0.771 | 0.565 | 0.892 |

| CP2 | 0.828 | |||

| CP3 | 0.727 | |||

| CP4 | 0.766 | |||

| CP5 | 0.803 | |||

| CP6 | 0.775 | |||

| CP7 | 0.683 | |||

| CP8 | 0.644 | |||

| Competitors’ pressure | CoP1 | 0.769 | 0.702 | 0.859 |

| CoP2 | 0.829 | |||

| CoP3 | 0.889 | |||

| CoP4 | 0.859 | |||

| Employee pressure | EP2 | 0.632 | 0.522 | 0.718 |

| EP3 | 0.81 | |||

| EP4 | 0.806 | |||

| EP6 | 0.62 | |||

| Environmental performance | EnP1 | 0.790 | 0.639 | 0.920 |

| EnP2 | 0.864 | |||

| EnP3 | 0.816 | |||

| EnP4 | 0.794 | |||

| EnP5 | 0.839 | |||

| EnP6 | 0.804 | |||

| EnP7 | 0.767 | |||

| EnP8 | 0.710 | |||

| Government pressure | GP1 | 0.686 | 0.524 | 0.849 |

| GP2 | 0.707 | |||

| GP3 | 0.649 | |||

| GP4 | 0.745 | |||

| GP5 | 0.772 | |||

| GP6 | 0.767 | |||

| GP7 | 0.732 | |||

| Green Practice Adoption | GPA1 | 0.778 | 0.547 | 0.909 |

| GPA2 | 0.719 | |||

| GPA3 | 0.722 | |||

| GPA4 | 0.757 | |||

| GPA5 | 0.803 | |||

| GPA6 | 0.786 | |||

| GPA7 | 0.715 | |||

| GPA8 | 0.791 | |||

| Senior Managers’ Pressure | SMP1 | 0.807 | 0.741 | 0.884 |

| SMP2 | 0.897 | |||

| SMP3 | 0.877 | |||

| SMP4 | 0.860 | |||

| Social Performance | SP1 | 0.800 | 0.701 | 0.860 |

| SP2 | 0.855 | |||

| SP3 | 0.838 | |||

| SP4 | 0.856 |

| CP | CoP | EP | EnP | GP | GPA | SMP | SP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CP | ||||||||

| CoP | 0.400 | |||||||

| EP | 0.619 | 0.679 | ||||||

| EnP | 0.458 | 0.716 | 0.728 | |||||

| GP | 0.552 | 0.697 | 0.707 | 0.778 | ||||

| GPA | 0.459 | 0.78 | 0.855 | 0.790 | 0.791 | |||

| SMP | 0.302 | 0.775 | 0.768 | 0.761 | 0.708 | 0.792 | ||

| SP | 0.357 | 0.681 | 0.684 | 0.839 | 0.658 | 0.719 | 0.729 |

| CP | CoP | EP | EnP | GP | GPA | SMP | SP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CP | 0.752 | |||||||

| CoP | 0.360 | 0.838 | ||||||

| EP | 0.469 | 0.541 | 0.723 | |||||

| EnP | 0.427 | 0.638 | 0.595 | 0.799 | ||||

| GP | 0.492 | 0.595 | 0.598 | 0.689 | 0.724 | |||

| GPA | 0.423 | 0.686 | 0.694 | 0.826 | 0.699 | 0.758 | ||

| SMP | 0.282 | 0.674 | 0.627 | 0.687 | 0.615 | 0.711 | 0.861 | |

| SP | 0.327 | 0.583 | 0.542 | 0.746 | 0.564 | 0.701 | 0.633 | 0.838 |

| Hypotheses | Std. Beta | Std. Error | t-Value | p Values | f2 | 95% LL | 95% UL | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SHP > EnP | 0.305 | 0.049 | 6.16 | 0 | 0.11 | 0.208 | 0.404 | S |

| SHP > SP | 0.297 | 0.065 | 4.58 | 0 | 0.063 | 0.175 | 0.422 | S |

| SHP > GPA | 0.210 | 0.018 | 11.67 | 0 | 1.934 | 0.77 | 0.841 | S |

| GPA > EnP | 0.578 | 0.05 | 11.57 | 0 | 0.398 | 0.475 | 0.669 | S |

| GPA > SP | 0.460 | 0.063 | 7.32 | 0 | 0.151 | 0.338 | 0.581 | S |

| Mediating Hypotheses | Std. Beta | Std. Error | t-Value | p Values | 95% LL | 95% UL | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SHP > GPA > EnP | 0.470 | 0.043 | 10.853 | 0 | 0.382 | 0.549 | S |

| SHP > GPA > SP | 0.374 | 0.053 | 7.068 | 0 | 0.27 | 0.479 | S |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Islam, M.S.; Rubel, M.R.B.; Hasan, M.M. Environmental and Social Performance of the Banking Industry in Bangladesh: Effect of Stakeholders’ Pressure and Green Practice Adoption. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8665. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15118665

Islam MS, Rubel MRB, Hasan MM. Environmental and Social Performance of the Banking Industry in Bangladesh: Effect of Stakeholders’ Pressure and Green Practice Adoption. Sustainability. 2023; 15(11):8665. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15118665

Chicago/Turabian StyleIslam, Md. Shajul, Mohammad Rabiul Basher Rubel, and Md. Mahedi Hasan. 2023. "Environmental and Social Performance of the Banking Industry in Bangladesh: Effect of Stakeholders’ Pressure and Green Practice Adoption" Sustainability 15, no. 11: 8665. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15118665

APA StyleIslam, M. S., Rubel, M. R. B., & Hasan, M. M. (2023). Environmental and Social Performance of the Banking Industry in Bangladesh: Effect of Stakeholders’ Pressure and Green Practice Adoption. Sustainability, 15(11), 8665. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15118665