Tourist Behavior in the Cruise Industry Post-COVID-19: An Examination of Service Quality, Corporate Image, and Intentions to Pay and Revisit

Abstract

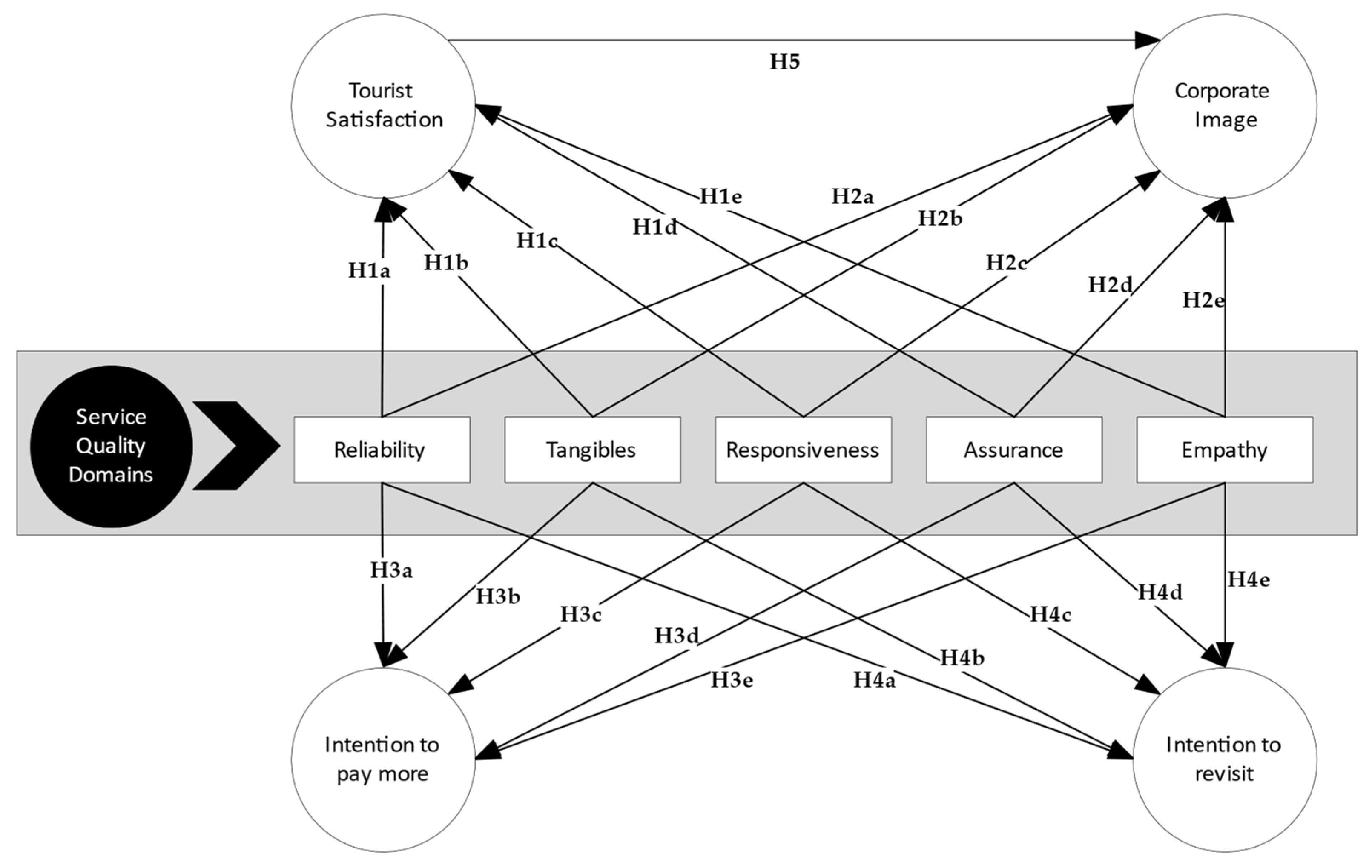

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. The COVID-19 Pandemic and the Cruise Industry

2.2. Service Quality and Its Impact on Tourist Satisfaction

2.3. Service Quality and Corporate Image

2.4. Service Quality and Intention to Pay More

2.5. Service Quality and Intention to Revisit the Destination

2.6. The Influence of Tourist Satisfaction on Corporate Image

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Sample and Data Collection

3.2. Construct Measures

3.3. Statistical Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Characteristics of the Respondents

4.2. Outcomes of Construct Reliability and Convergent Validity

4.3. Outcomes of the Discriminant Validity

4.4. Structural Model

5. Discussion and Limitations

6. Conclusions and Future Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Construct | Item Code | Item |

|---|---|---|

| Service Quality (Reliability) | Rel_1 | Itinerary and departure/arrival time compliance: When the cruise ship promises to do something by a certain time, it does so. |

| Rel_2 | When customers have problems, the cruise ship is sympathetic and reassuring. | |

| Rel_3 | Cruise ship is dependable. | |

| Rel_4 | Cruise onboard programs are on time: Cruise ship provides its services at the time it promises to do so. | |

| Rel_5 | Cruise ship keeps its records accurately. | |

| Service Quality (Tangibles) | Tan_1 | Ship facts: Cruise ship’s facilities have up-to-date equipment. |

| Tan_2 | Ship’s interior style, cabin, cleanness: Cruise ship’s facilities are visually appealing. | |

| Tan_3 | Crew members’ appearance: Crew members are well-dressed and appear neat. | |

| Tan_4 | Service materials, other cruise guests: The appearance of the physical facilities of cruise ship is in keeping with the type of services provided. | |

| Service Quality (Responsiveness) | Resp_1 | They tell customers exactly when services will be performed. |

| Resp_2 | Receive prompt service from crew members. | |

| Resp_3 | Crew members are always willing to help customers. | |

| Resp_4 | Crew members are too busy to respond to customer requests promptly. | |

| Service Quality (Assurance) | Assurance_1 | Customers can trust crew members. |

| Assurance_2 | Announcements for safety and lifeboat drills: Customers feel safe in their transactions with crew members. | |

| Assurance_3 | Crew members are polite. | |

| Assurance_4 | Crew members get adequate support from cruise lines to do their jobs well. | |

| Service Quality (Empathy) | Emp_1 | These cruise lines give customers individual attention. |

| Emp_2 | Crew members of cruise lines give customers personal attention. | |

| Emp_3 | Crew members of cruise lines know what customers need. | |

| Emp_4 | These cruise lines have customer’s best interests at heart. | |

| Emp_5 | These cruise lines have operating hours convenient to all their customers. | |

| Tourist Satisfaction | Satisfaction_1 | The duration of the cruise trip was adequate for me to explore the attractions I wanted to explore. |

| Satisfaction_2 | The cruise ship serves my needs and expectations. | |

| Satisfaction_3 | The safety precautions and measures are adequately taken before the cruise. | |

| Satisfaction_4 | The quality of the food and services provided on board the cruise satisfied my needs. | |

| Satisfaction_5 | The quality of service that I received was higher than I expected. | |

| Satisfaction_6 | The quality of service that I received was as I imagined. | |

| Corporate Image | Img_1 | Has a good reputation in the eyes of tourists. |

| Img_2 | Has a good image in the minds of passengers. | |

| Intention to Pay more | Pay_1 | I would be willing to pay more money for additional activities on a cruise. |

| Pay_2 | I do not have a maximum amount of money I would be willing to spend on additional activities on a cruise. | |

| Pay_3 | I intend to pay extra money for tourism activities on the cruise. | |

| Intention to Revisit | Vis_1 | I want to visit the cruise line within the next two years. |

| Vis_2 | The possibility for me to use the cruise line soon is high. | |

| Vis_3 | The cruise line could be my next vacation place. | |

| Vis_4 | I intend to travel on the cruise line sometime during my next vacation. |

Appendix B

| Domain | B-HTMT Values (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| Satisfaction → Rel | 0.769 (0.681 to 0.842) |

| Satisfaction → Tan | 0.866 (0.806 to 0.914) |

| Satisfaction → Resp | 0.941 (0.898 to 0.985) |

| Satisfaction → Assurance | 0.897 (0.842 to 0.942) |

| Satisfaction → Emp | 0.933 (0.893 to 0.968) |

| Satisfaction → Img | 0.950 (0.881 to 1.024) |

| Satisfaction → Pay | 0.961 (0.917 to 1.005) |

| Satisfaction → Vis | 0.885 (0.816 to 0.945) |

| Rel → Tan | 0.700 (0.602 to 0.782) |

| Rel → Resp | 0.762 (0.665 to 0.849) |

| Rel → Assurance | 0.693 (0.575 to 0.798) |

| Rel → Emp | 0.713 (0.618 to 0.792) |

| Rel → Img | 0.685 (0.557 to 0.790) |

| Rel → Pay | 0.808 (0.702 to 0.897) |

| Rel → Vis | 0.753 (0.664 to 0.838) |

| Tan → Resp | 0.901 (0.832 to 0.956) |

| Tan → Assurance | 0.829 (0.763 to 0.889) |

| Tan → Emp | 0.899 (0.846 to 0.946) |

| Tan → Img | 0.797 (0.695 to 0.891) |

| Tan → Pay | 0.788 (0.700 to 0.861) |

| Tan → Vis | 0.786 (0.704 to 0.864) |

| Resp → Assurance | 0.976 (0.936 to 1.014) |

| Resp → Emp | 0.929 (0.886 to 0.970) |

| Resp → Img | 0.824 (0.730 to 0.910) |

| Resp → Pay | 0.885 (0.813 to 0.946) |

| Resp → Vis | 0.848 (0.773 to 0.915) |

| Assurance → Emp | 0.880 (0.828 to 0.926) |

| Assurance → Img | 0.851 (0.756 to 0.931) |

| Assurance → Pay | 0.849 (0.779 to 0.910) |

| Assurance → Vis | 0.789 (0.708 to 0.864) |

| Emp → Img | 0.796 (0.703 to 0.882) |

| Emp → Pay | 0.846 (0.784 to 0.904) |

| Emp → Vis | 0.855 (0.788 to 0.915) |

| Img → Pay | 0.977 (0.907 to 1.049) |

| Img → Vis | 0.887 (0.787 to 0.976) |

| Pay → Vis | 0.887 (0.814 to 0.955) |

References

- CLIA State of the Cruise Industry Outlook. Available online: https://cruising.org/-/media/research-updates/research/2021-state-of-the-cruise-industry_optimized.ashx (accessed on 4 April 2023).

- Grönroos, C. A service quality model and its marketing implications. Eur. J. Mark. 1984, 18, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasuraman, A.; Zeithaml, V.A.; Berry, L. SERVQUAL: A multiple-item scale for measuring consumer perceptions of service quality. J. Retail. 1988, 64, 12–40. [Google Scholar]

- Parasuraman, A.; Zeithaml, V.A.; Berry, L.L. A conceptual model of service quality and its implications for future research. J. Mark. 1985, 49, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrick, J.F. The roles of quality, value, and satisfaction in predicting cruise passengers’ behavioral intentions. J. Travel Res. 2004, 42, 397–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen Viet, B.; Dang, H.P.; Nguyen, H.H. Revisit intention and satisfaction: The role of destination image, perceived risk, and cultural contact. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2020, 7, 1796249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ćulić, M.; Vujičić, M.D.; Kalinić, Č.; Dunjić, M.; Stankov, U.; Kovačić, S.; Vasiljević, Đ.A.; Anđelković, Ž. Rookie Tourism Destinations—The Effects of Attractiveness Factors on Destination Image and Revisit Intention with the Satisfaction Mediation Effect. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, W.-C.; Wan Ibrahim, W.H.; Lo, M.-C.; Mohamad, A.A.; Ramayah, T.; Chin, C.-H. Controllable drivers that influence tourists’ satisfaction and revisit intention to Semenggoh Nature Reserve: The moderating impact of destination image. J. Ecotourism 2022, 21, 147–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigné, J.E.; Sánchez, M.I.; Sánchez, J. Tourism image, evaluation variables and after purchase behaviour: Inter-relationship. Tour. Manag. 2001, 22, 607–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.-K.; Lee, Y.-K.; Lee, B. Korea’s destination image formed by the 2002 World Cup. Ann. Tour. Res. 2005, 32, 839–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mechinda, P.; Serirat, S.; Gulid, N. An examination of tourists’ attitudinal and behavioral loyalty: Comparison between domestic and international tourists. J. Vacat. Mark. 2009, 15, 129–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilplub, C.; Khang, D.B.; Krairit, D. Determinants of destination loyalty and the mediating role of tourist satisfaction. Tourism Analysis 2016, 21, 221–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Pennington-Gray, L.; Krieger, J. Tourism crisis management: Can the Extended Parallel Process Model be used to understand crisis responses in the cruise industry? Tour. Manag. 2016, 55, 310–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liska, A.E. A critical examination of the causal structure of the Fishbein/Ajzen attitude-behavior model. Soc. Psychol. Q. 1984, 47, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, T.; Shu, F.; Kitterlin-Lynch, M.; Beckman, E. Perceptions of cruise travel during the COVID-19 pandemic: Market recovery strategies for cruise businesses in North America. Tour. Manag. 2021, 85, 104275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orden-Mejía, M.; Carvache-Franco, M.; Huertas, A.; Carvache-Franco, W.; Landeta-Bejarano, N.; Carvache-Franco, O. Post-COVID-19 Tourists’ Preferences, Attitudes and Travel Expectations: A Study in Guayaquil, Ecuador. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, Y.; Cha, K.C. A Qualitative Review of Cruise Service Quality: Case Studies from Asia. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, J.; Mazzarol, T.; Soutar, G.N.; Tapsall, S.; Elliott, W.A. Cruising through a pandemic: The impact of COVID-19 on intentions to cruise. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2021, 9, 100328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, A.U.; Abbas, M.; Abbasi, F.A.; Khan, S. How Tourist Experience Quality, Perceived Price Reasonableness and Regenerative Tourism Involvement Influence Tourist Satisfaction: A study of Ha’il Region, Saudi Arabia. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, T.H.; Salem, A.E.; Abdelmoaty, M.A. Impact of Rural Tourism Development on Residents’ Satisfaction with the Local Environment, Socio-Economy and Quality of Life in Al-Ahsa Region, Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Maritime Executive Saudi Arabia Aims to Attract Cruise Ships with New Port Investments. Available online: https://maritime-executive.com/article/saudi-arabia-aims-to-attract-cruise-ships-with-new-port-investments (accessed on 14 May 2023).

- Cruise Industry News Cruise Saudi Joins Saudi Tourism Forum. Available online: https://cruiseindustrynews.com/cruise-news/2023/03/cruise-saudi-joins-saudi-tourism-forum/ (accessed on 14 May 2023).

- Papathanassis, A.; Beckmann, I. Assessing the ‘poverty of cruise theory’hypothesis. Ann. Tour. Res. 2011, 38, 153–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, B.-L.; Lee, S.; Goh, B.; Han, H. Impacts of cruise service quality and price on vacationers’ cruise experience: Moderating role of price sensitivity. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 44, 131–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Petrick, J.F. Towards an integrative model of loyalty formation: The role of quality and value. Leis. Sci. 2010, 32, 201–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monferrer, D.; Segarra, J.R.; Estrada, M.; Moliner, M.Á. Service quality and customer loyalty in a post-crisis context. Prediction-oriented modeling to enhance the particular importance of a social and sustainable approach. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, P.; Hillier, D.; Comfort, D. The two market leaders in ocean cruising and corporate sustainability. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 29, 288–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryce, K.R. The role of social media in crisis management at Carnival Cruise Line. J. Bus. Case Stud. (JBCS) 2014, 10, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwortnik, R.J. Shipscape influence on the leisure cruise experience. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2008, 2, 289–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Vaio, A.; Varriale, L.; Lekakou, M.; Stefanidaki, E. Cruise and container shipping companies: A comparative analysis of sustainable development goals through environmental sustainability disclosure. Marit. Policy Manag. 2021, 48, 184–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renaud, L. Reconsidering global mobility–distancing from mass cruise tourism in the aftermath of COVID-19. Tour. Geogr. 2020, 22, 679–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennigs, N.; Schmidt, S.; Wiedmann, K.-P.; Karampournioti, E.; Labenz, F. Measuring brand performance in the cruise industry: Brand experiences and sustainability orientation as basis for value creation. Int. J. Serv. Technol. Manag. 2017, 23, 189–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Könnölä, K.; Kangas, K.; Seppälä, K.; Mäkelä, M.; Lehtonen, T. Considering sustainability in cruise vessel design and construction based on existing sustainability certification systems. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 259, 120763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Manzano, J.I.; Castro-Nuño, M.; Pozo-Barajas, R. Addicted to cruises? Key drivers of cruise ship loyalty behavior through an e-WOM approach. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 34, 361–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S.; Scott, D.; Hall, C.M. Pandemics, tourism and global change: A rapid assessment of COVID-19. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 29, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhang, P.; Tong, H. The labor market of Chinese cruise seafarers: Demand, opportunities, and challenges. Marit. Technol. Res. 2020, 2, 243–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manolitzas, P.; Glaveli, N.; Palamas, S.; Grigoroudis, E.; Zopounidis, C. Improving customer experience in the cruise industry in the post pandemic era. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2022, 9, 2143309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Ye, Q.; Song, H.; Liu, T. The structure of customer satisfaction with cruise-line services: An empirical investigation based on online word of mouth. Curr. Issues Tour. 2015, 18, 450–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krieger, B.; Moskowitz, H.; Rabino, S. What customers want from a cruise vacation: Using internet-enabled conjoint analysis to understand the customer’s mind. J. Hosp. Leis. Mark. 2005, 13, 83–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajagunna, I.; Ilori, M.O.; McLean, E. An analysis of post-pandemic scenarios: What are the prospects for the Caribbean cruise industry? Worldwide Hospitality and Tourism Themes 2022, 14, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muritala, B.A.; Hernández-Lara, A.-B.; Sánchez-Rebull, M.-V.; Perera-Lluna, A. #CoronavirusCruise: Impact and implications of the COVID-19 outbreaks on the perception of cruise tourism. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2022, 41, 100948. [Google Scholar]

- Tapsall, S.; Soutar, G.N.; Elliott, W.A.; Mazzarol, T.; Holland, J. COVID-19’s impact on the perceived risk of ocean cruising: A best-worst scaling study of Australian consumers. Tour. Econ. 2022, 28, 248–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soleimani, A.G.; Einolahzadeh, H. The influence of service quality on revisit intention: The mediating role of WOM and satisfaction (Case study: Guilan travel agencies). Cogent Soc. Sci. 2018, 4, 1560651. [Google Scholar]

- Jayasinghe, P. Impact of service quality dimensions on tourist satisfaction (Case study on Passikuda hotels). Int. J. Adv. Res. Innov. Ideas Educ. 2020, 7, 520–534. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, G.; Malviya, S. Internet banking service quality and its impact on customer satisfaction in Indore district of Madhya Pradesh. Int. J. Bus. Manag. Invent. 2014, 3, 2319–8028. [Google Scholar]

- Kitapci, O.; Taylan Dortyol, I.; Yaman, Z.; Gulmez, M. The paths from service quality dimensions to customer loyalty. Manag. Res. Rev. 2013, 36, 239–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimou, I.; Velissariou, E. Tourism and Accessibility. A satisfaction survey on tourists with disabilities in the Island of Crete. In Proceedings of the 11th Management of Innovative Business, Education & Support Systems, Heraklion, Greece, 22–24 June 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Melian, A.; Prats, L.; Coromina, L. The perceived value of accessibility in religious sites–do disabled and non-disabled travellers behave differently? Tour. Rev. 2016, 71, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zygiaris, S.; Hameed, Z.; Ayidh Alsubaie, M.; Ur Rehman, S. Service Quality and Customer Satisfaction in the Post Pandemic World: A Study of Saudi Auto Care Industry. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 842141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahhal, W. The effects of service quality dimensions on customer satisfaction: An empirical investigation in Syrian mobile telecommunication services. Int. J. Bus. Manag. Invent. 2015, 4, 81–89. [Google Scholar]

- Chun, R. Corporate reputation: Meaning and measurement. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2005, 7, 91–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarimoglu, E.K. A review on dimensions of service quality models. J. Mark. Manag. 2014, 2, 79–93. [Google Scholar]

- Jansri, W.; Hussein, L.A.; Loo, J.T.K. The effect of service quality on revisit intention in tourist beach. GeoJ. Tour. Geosites 2020, 29, 472–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özkan, P.; Süer, S.; Keser, İ.K.; Kocakoç, İ.D. The effect of service quality and customer satisfaction on customer loyalty. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2019, 38, 384–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.M.D.; Noor, N.A.M. The Relationship Between Service Quality, Corporate Image, and Customer Loyalty of Generation Y: An Application of S-O-R Paradigm in the Context of Superstores in Bangladesh. SAGE Open 2020, 10, 215824402092440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishaq, I. Perceived value, service quality, corporate image and customer loyalty: Empirical assessment from Pakistan. Serb. J. Manag. 2012, 7, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadissa, B. Service Quality and Tourists Satisfaction the Case of Seven Travel Agents in Addis Ababa. Ph.D. Thesis, St. Mary’s University, Winona, MN, USA, January 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Casidy, R.; Wymer, W. A risk worth taking: Perceived risk as moderator of satisfaction, loyalty, and willingness-to-pay premium price. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 32, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.; Park, H.-S.; Choi, W.; Jun, H. The Relationships between Service Quality, Satisfaction, and Purchase Intention of Customers at Non-Profit Business. Int. J. Bus. Mark. Manag. 2017, 2, 12–19. [Google Scholar]

- Homburg, C.; Koschate, N.; Hoyer, W.D. Do Satisfied Customers Really Pay More? A Study of the Relationship between Customer Satisfaction and Willingness to Pay. J. Mark. 2005, 69, 84–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawi, N.; Jusoh, A.; Streimikis, J.; Mardani, A. The influence of service quality on customer satisfaction and customer behavioral intentions by moderating role of switching barriers in satellite pay TV market. Econ. Sociol. 2018, 11, 198–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keiningham, T.; Gupta, S.; Aksoy, L.; Buoye, A. The High Price of Customer Satisfaction. MIT Sloan Managment Review. 2014. Available online: https://sloanreview.mit.edu/article/the-high-price-of-customer-satisfaction/ (accessed on 14 April 2023).

- Tosun, C.; Dedeoğlu, B.B.; Fyall, A. Destination service quality, affective image and revisit intention: The moderating role of past experience. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2015, 4, 222–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boro, K. Destination service quality, tourist satisfaction and revisit intention: The moderating role of income and occupation of tourist. J. Tour. Hosp. Culin. Arts 2022, 14, 23–40. [Google Scholar]

- Wantara, P.; Irawati, S.A. Relationship and Impact of Service Quality, Destination Image, on Customer Satisfaction and Revisit Intention to Syariah Destination in Madura, Indonesia. Eur. J. Bus. Manag. Res. 2021, 6, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobni, D.; Zinkhan, G.M. In search of brand image: A foundation analysis. ACR North Am. Adv. 1990, 17, 110–119. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.; Hu, S.; Feng, L.; Lu, Y. Tourism Destination Image Perception Model Based on Clustering and PCA from the Perspective of New Media and Wireless Communication Network: A Case Study of Leshan. Wirel. Commun. Mob. Comput. 2022, 2022, 8630927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adnyana, I.P.; Teja Kusuma, G.; Kepramareni, P.; Landra, N. Destination Image as a Strategy to Save the Negative Effects of Risk Perception on Attitudes and Intentions of Tourists Visits During Post Eruption of Mount Agung in Bali. J. Adv. Res. Dyn. Control. Syst. 2020, 12, 834–848. [Google Scholar]

- Dirsehan, T.; Kurtuluş, S. Measuring brand image using a cognitive approach: Representing brands as a network in the Turkish airline industry. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2018, 67, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, K.L. Conceptualizing, measuring, and managing customer-based brand equity. J. Mark. 1993, 57, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-S.; Hsu, L.-T.; Han, H.; Kim, Y. Understanding how consumers view green hotels: How a hotel’s green image can influence behavioural intentions. J. Sustain. Tour. 2010, 18, 901–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Park, S. An exploratory study of how casino dealer communication styles lead to player satisfaction. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2018, 35, 1246–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Hwang, J.; Lee, M.J.; Kim, J. Word-of-mouth, buying, and sacrifice intentions for eco-cruises: Exploring the function of norm activation and value-attitude-behavior. Tour. Manag. 2019, 70, 430–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Eom, T.; Chung, H.; Lee, S.; Ryu, H.B.; Kim, W. Passenger repurchase behaviours in the green cruise line context: Exploring the role of quality, image, and physical environment. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Hyun, S.S. Cruise travel motivations and repeat cruising behaviour: Impact of relationship investment. Curr. Issues Tour. 2019, 22, 786–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Hwang, J.; Lee, M.J. Antecedents of travellers’ repurchase behaviour for luxury cruise product. Curr. Issues Tour. 2018, 21, 821–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladhari, R. A review of twenty years of SERVQUAL research. Int. J. Qual. Serv. Sci. 2009, 1, 172–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasuraman, A.; Berry, L.; Zeithaml, V. Refinement and reassessment of the SERVQUAL scale. J. Retail. 2002, 67, 114. [Google Scholar]

- Babakus, E.; Boller, G.W. An empirical assessment of the SERVQUAL scale. J. Bus. Res. 1992, 24, 253–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, T.H.; Salem, A.E. Impact of Service Quality of Low-Cost Carriers on Airline Image and Consumers’ Satisfaction and Loyalty during the COVID-19 Outbreak. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 19, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zinko, R.; Furner, C.P.; de Burgh-Woodman, H.; Johnson, P.; Sluhan, A. The Addition of Images to eWOM in the Travel Industry: An Examination of Hotels, Cruise Ships and Fast Food Reviews. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2021, 16, 525–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jöreskog, K.G. Simultaneous factor analysis in several populations. Psychometrika 1971, 36, 409–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkstra, T.K.; Henseler, J. Consistent partial least squares path modeling. MIS Q. 2015, 39, 297–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. Assessing PLS-SEM Results—Part I: Evaluation of the Reflective Measeurement Models. In A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 3rd ed.; Hair, J.F., Jr., Hult, G.T.M., Ringle, C.M., Sarstedt, M., Eds.; Sage Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streukens, S.; Leroi-Werelds, S. Bootstrapping and PLS-SEM: A step-by-step guide to get more out of your bootstrap results. Eur. Manag. J. 2016, 34, 618–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, J.-M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Völckner, F. How collinearity affects mixture regression results. Mark. Lett. 2015, 26, 643–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello, Y.O.; Majebi, E.C. Lodging quality index approach: Exploring the relationship between service quality and customers satisfaction in hotel industry. J. Tour. Herit. Stud. 2018, 7, 58–78. [Google Scholar]

- Thi, K.C.N.; Huy, T.L.; Van, C.H.; Tuan, P.C. The effects of service quality on international tourist satisfaction and loyalty: Insight from Vietnam. Int. J. Data Netw. Sci. 2020, 4, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerdpitak, C.; Heuer, K. Key Success Factors of Tourist Satisfaction In Tourism Services Provider. J. Appl. Bus. Res. (JABR) 2016, 32, 1237–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydin, S.; Özer, G. The analysis of antecedents of customer loyalty in the Turkish mobile telecommunication market. Eur. J. Mark. 2005, 39, 910–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Fu, S.; Sun, J.; Bilgihan, A.; Okumus, F. An investigation on online reviews in sharing economy driven hospitality platforms: A viewpoint of trust. Tour. Manag. 2019, 71, 366–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.S.; Zhang, J.J.; Kim, D.H.; Chen, K.K.; Henderson, C.; Min, S.D.; Huang, H. Service Quality, Perceived Value, Customer Satisfaction, and Behavioral Intention Among Fitness Center Members Aged 60 Years and Over. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2014, 42, 757–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slack, N.; Singh, G.; Sharma, S. The effect of supermarket service quality dimensions and customer satisfaction on customer loyalty and disloyalty dimensions. Int. J. Qual. Serv. Sci. 2020, 12, 297–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoch, S.J.; Deighton, J. Managing What Consumers Learn from Experience. J. Mark. 1989, 53, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliman, N.K.; Mohamad, W.N. Linking Service Quality, Patients’ Satisfaction and Behavioral Intentions: An Investigation on Private Healthcare in Malaysia. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 224, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.-H.S.; Lee, T. Service quality and price perception of service: Influence on word-of-mouth and revisit intention. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2016, 52, 42–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wang, X.; Li, X.; Yuen, K.F. Post COVID-19: Health crisis management for the cruise industry. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2022, 71, 102792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rius, J.M.; Gassiot-Melian, A. Has COVID-19 had an impact on prices. J. Revenue Pricing Manag. 2021, 21, 538–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryschka, A.M.; Domke-Damonte, D.J.; Keels, J.K.; Nagel, R. The effect of social media on reputation during a crisis event in the cruise line industry. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2016, 17, 198–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Category | N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 146 (46.3%) |

| Female | 169 (53.7%) | |

| Age (years) | ≤20 | 60 (19.0%) |

| 21 to 30 | 111 (35.2%) | |

| 31 to 40 | 99 (31.4%) | |

| 41 to 50 | 30 (9.5%) | |

| 51 to 60 | 13 (4.1%) | |

| >60 | 2 (0.6%) | |

| Education level | Junior high school (or below) | 21 (6.7%) |

| High school | 164 (52.1%) | |

| College or university | 95 (30.2%) | |

| Master | 26 (8.3%) | |

| Doctorate | 9 (2.9%) | |

| Occupation | Student | 87 (27.6%) |

| Army, civil service, and education | 97 (30.8%) | |

| Service industry | 82 (26.0%) | |

| Self-employed | 41 (13.0%) | |

| Other | 8 (2.5%) | |

| Number of cruise trips taken | 1 | 111 (35.2%) |

| 2 to 3 | 181 (57.5%) | |

| 4 to 5 | 20 (6.3%) | |

| ≥6 | 3 (1.0%) |

| Domains/Items | BFL | VIF | Alpha | rhoC | rhoA | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Service Quality (Reliability) | 0.859 | 0.905 | 0.866 | 0.707 | ||

| Rel_1 | 0.734 | 1.529 | ||||

| Rel_2 | 0.900 | 2.937 | ||||

| Rel_3 | 0.844 | 2.466 | ||||

| Rel_4 | 0.868 | 2.298 | ||||

| Service Quality (Tangibles) | 0.864 | 0.906 | 0.878 | 0.708 | ||

| Tan_1 | 0.815 | 2.492 | ||||

| Tan_2 | 0.841 | 2.541 | ||||

| Tan_3 | 0.889 | 2.518 | ||||

| Tan_4 | 0.816 | 1.808 | ||||

| Service Quality (Responsiveness) | 0.815 | 0.878 | 0.817 | 0.644 | ||

| Resp_1 | 0.844 | 1.994 | ||||

| Resp_2 | 0.776 | 1.682 | ||||

| Resp_3 | 0.782 | 1.587 | ||||

| Resp_4 | 0.803 | 1.781 | ||||

| Service Quality (Assurance) | 0.896 | 0.928 | 0.895 | 0.764 | ||

| Assurance_1 | 0.790 | 1.670 | ||||

| Assurance_2 | 0.899 | 3.148 | ||||

| Assurance_3 | 0.889 | 3.404 | ||||

| Assurance_4 | 0.910 | 3.734 | ||||

| Service Quality (Empathy) | 0.904 | 0.929 | 0.905 | 0.723 | ||

| Emp_1 | 0.842 | 2.651 | ||||

| Emp_2 | 0.873 | 3.060 | ||||

| Emp_3 | 0.853 | 2.492 | ||||

| Emp_4 | 0.831 | 2.264 | ||||

| Emp_5 | 0.846 | 2.260 | ||||

| Tourist Satisfaction | 0.876 | 0.906 | 0.878 | 0.617 | ||

| Satisfaction_1 | 0.778 | 1.886 | ||||

| Satisfaction_2 | 0.803 | 2.073 | ||||

| Satisfaction_3 | 0.773 | 1.827 | ||||

| Satisfaction_4 | 0.768 | 1.820 | ||||

| Satisfaction_5 | 0.778 | 1.941 | ||||

| Satisfaction_6 | 0.805 | 1.996 | ||||

| Corporate Image | 0.761 | 0.893 | 0.767 | 0.807 | ||

| Img_1 | 0.910 | 1.606 | ||||

| Img_2 | 0.886 | 1.606 | ||||

| Intention to Pay More | 0.846 | 0.907 | 0.847 | 0.764 | ||

| Pay_1 | 0.879 | 2.234 | ||||

| Pay_2 | 0.881 | 2.330 | ||||

| Pay_3 | 0.860 | 1.800 | ||||

| Intention to Revisit | 0.851 | 0.931 | 0.852 | 0.870 | ||

| Vis_1 | 0.936 | 2.212 | ||||

| Vis_2 | 0.929 | 2.212 |

| Construct | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Tourist Satisfaction | 0.786 | ||||||||

| 2. Service Quality (Reliability) | 0.670 | 0.841 | |||||||

| 3. Service Quality (Tangibles) | 0.772 | 0.622 | 0.841 | ||||||

| 4. Service Quality (Responsiveness) | 0.739 | 0.641 | 0.770 | 0.803 | |||||

| 5. Service Quality (Assurance) | 0.728 | 0.614 | 0.749 | 0.736 | 0.874 | ||||

| 6. Service Quality (Empathy) | 0.633 | 0.631 | 0.811 | 0.799 | 0.796 | 0.850 | |||

| 7. Corporate Image | 0.781 | 0.560 | 0.656 | 0.649 | 0.705 | 0.662 | 0.898 | ||

| 8. Intention to Pay More | 0.732 | 0.693 | 0.693 | 0.736 | 0.744 | 0.744 | 0.787 | 0.874 | |

| 9. Intention to Revisit | 0.767 | 0.644 | 0.690 | 0.707 | 0.694 | 0.750 | 0.715 | 0.756 | 0.933 |

| Relationship | t Value | Beta (95%CI) | p-Value | Hypothesis | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tourist Satisfaction | |||||

| Rel → Sat | 3.163 | 0.144 (0.054 to 0.232) | 0.001 | H1a | Accept |

| Tan → Sat | 1.668 | 0.117 (−0.025 to 0.253) | 0.058 | H1b | Accept |

| Resp → Sat | 2.59 | 0.160 (0.045 to 0.284) | 0.005 | H1c | Accept |

| Assurance → Sat | 3.132 | 0.202 (0.078 to 0.333) | 0.001 | H1d | Accept |

| Emp → Sat | 5.298 | 0.359 (0.230 to 0.491) | <0.0001 | H1e | Accept |

| Corporate Image | |||||

| Rel → Img | 0.722 | 0.040 (−0.076 to 0.141) | 0.235 | H2a | Reject |

| Tan → Img | 1.486 | 0.114 (−0.030 to 0.271) | 0.069 | H2b | Reject |

| Resp → Img | −1.155 | −0.096 (−0.256 to 0.074) | 0.876 | H2c | Reject |

| Assurance → Img | 2.933 | 0.268 (0.067 to 0.423) | 0.002 | H2d | Accept |

| Emp → Img | −1.382 | −0.108 (−0.252 to 0.062) | 0.916 | H2e | Reject |

| Sat → Img | 7.168 | 0.619 (0.448 to 0.785) | <0.0001 | H5 | Accept |

| Intention to Pay More | |||||

| Rel → Pay | 4.595 | 0.287 (0.157 to 0.407) | <0.0001 | H3a | Accept |

| Tan → Pay | 0.573 | 0.049 (−0.126 to 0.203) | 0.283 | H3b | Reject |

| Resp → Pay | 1.498 | 0.134 (−0.023 to 0.325) | 0.068 | H3c | Reject |

| Assurance → Pay | 2.975 | 0.239 (0.086 to 0.389) | 0.002 | H3d | Accept |

| Emp → Pay | 2.562 | 0.226 (0.059 to 0.404) | 0.005 | H3e | Accept |

| Intention to Revisit | |||||

| Rel → Vis | 3.513 | 0.218 (0.105 to 0.344) | <0.0001 | H4a | Accept |

| Tan → Vis | 1.001 | 0.093 (−0.091 to 0.274) | 0.159 | H4b | Reject |

| Resp → Vis | 1.511 | 0.128 (−0.036 to 0.286) | 0.066 | H4c | Reject |

| Assurance → Vis | 1.294 | 0.103 (−0.049 to 0.249) | 0.098 | H4d | Reject |

| Emp → Vis | 3.234 | 0.352 (0.143 to 0.572) | 0.001 | H4e | Accept |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alonazi, B.S.; Hassan, T.H.; Abdelmoaty, M.A.; Salem, A.E.; Saleh, M.I.; Helal, M.Y.; Mohamed, Y.A.; Abuelnasr, M.S.; Gebreslassie, D.A.; Aleedan, M.H.; et al. Tourist Behavior in the Cruise Industry Post-COVID-19: An Examination of Service Quality, Corporate Image, and Intentions to Pay and Revisit. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8623. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15118623

Alonazi BS, Hassan TH, Abdelmoaty MA, Salem AE, Saleh MI, Helal MY, Mohamed YA, Abuelnasr MS, Gebreslassie DA, Aleedan MH, et al. Tourist Behavior in the Cruise Industry Post-COVID-19: An Examination of Service Quality, Corporate Image, and Intentions to Pay and Revisit. Sustainability. 2023; 15(11):8623. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15118623

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlonazi, Bodur S., Thowayeb H. Hassan, Mostafa A. Abdelmoaty, Amany E. Salem, Mahmoud I. Saleh, Mohamed Y. Helal, Yasser Ahmed Mohamed, Magdy Sayed Abuelnasr, Daniel Alemshet Gebreslassie, Mona Hamad Aleedan, and et al. 2023. "Tourist Behavior in the Cruise Industry Post-COVID-19: An Examination of Service Quality, Corporate Image, and Intentions to Pay and Revisit" Sustainability 15, no. 11: 8623. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15118623

APA StyleAlonazi, B. S., Hassan, T. H., Abdelmoaty, M. A., Salem, A. E., Saleh, M. I., Helal, M. Y., Mohamed, Y. A., Abuelnasr, M. S., Gebreslassie, D. A., Aleedan, M. H., & Radwan, S. H. (2023). Tourist Behavior in the Cruise Industry Post-COVID-19: An Examination of Service Quality, Corporate Image, and Intentions to Pay and Revisit. Sustainability, 15(11), 8623. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15118623