Determinants of Organic Food Consumption in Narrowing the Green Gap

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

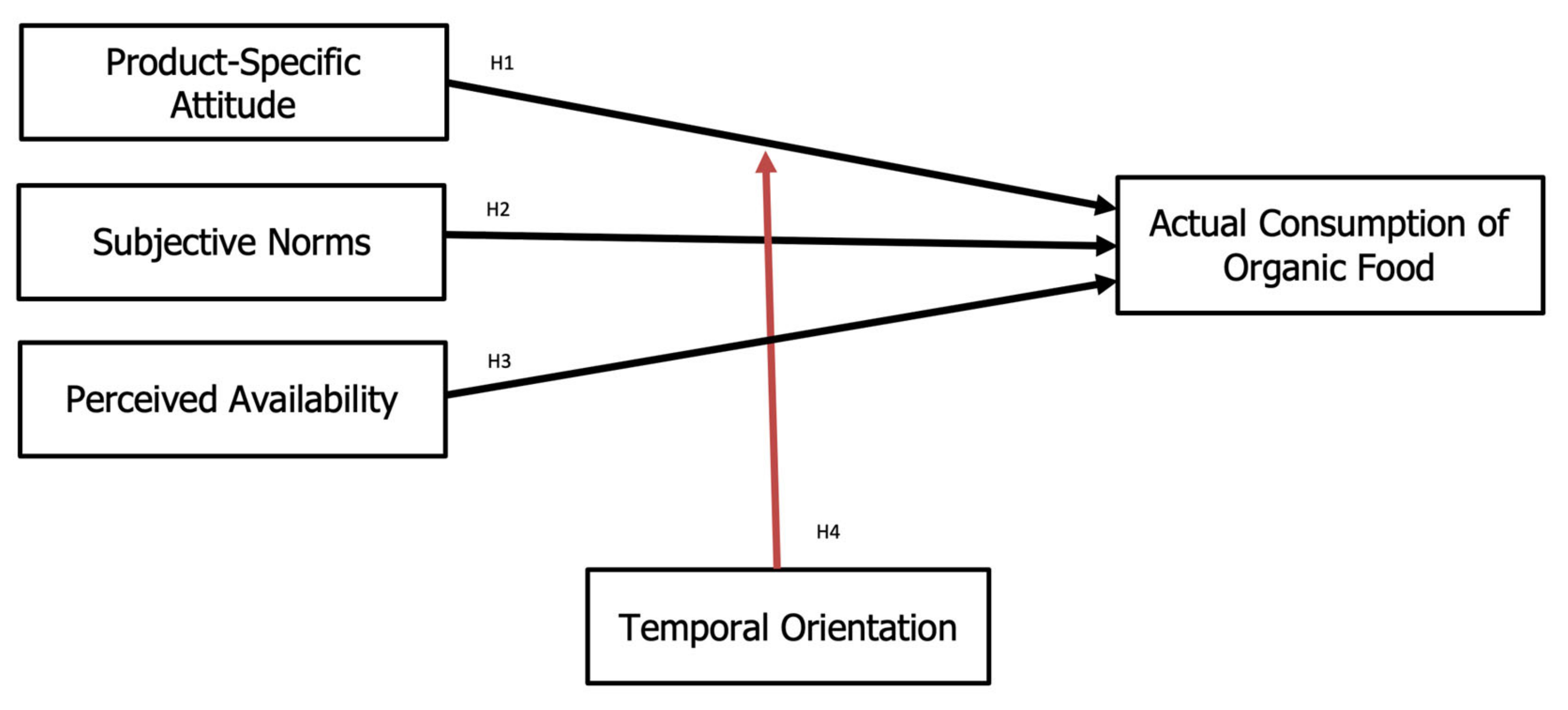

2.1. Underpinning Theory

2.2. Product-Specific Attitude

2.3. Subjective Norms

2.4. Perceived Availability

2.5. Future Orientation

3. Methodology

4. Results

4.1. Profile of Respondents

4.2. Assessment of the Measurement Model

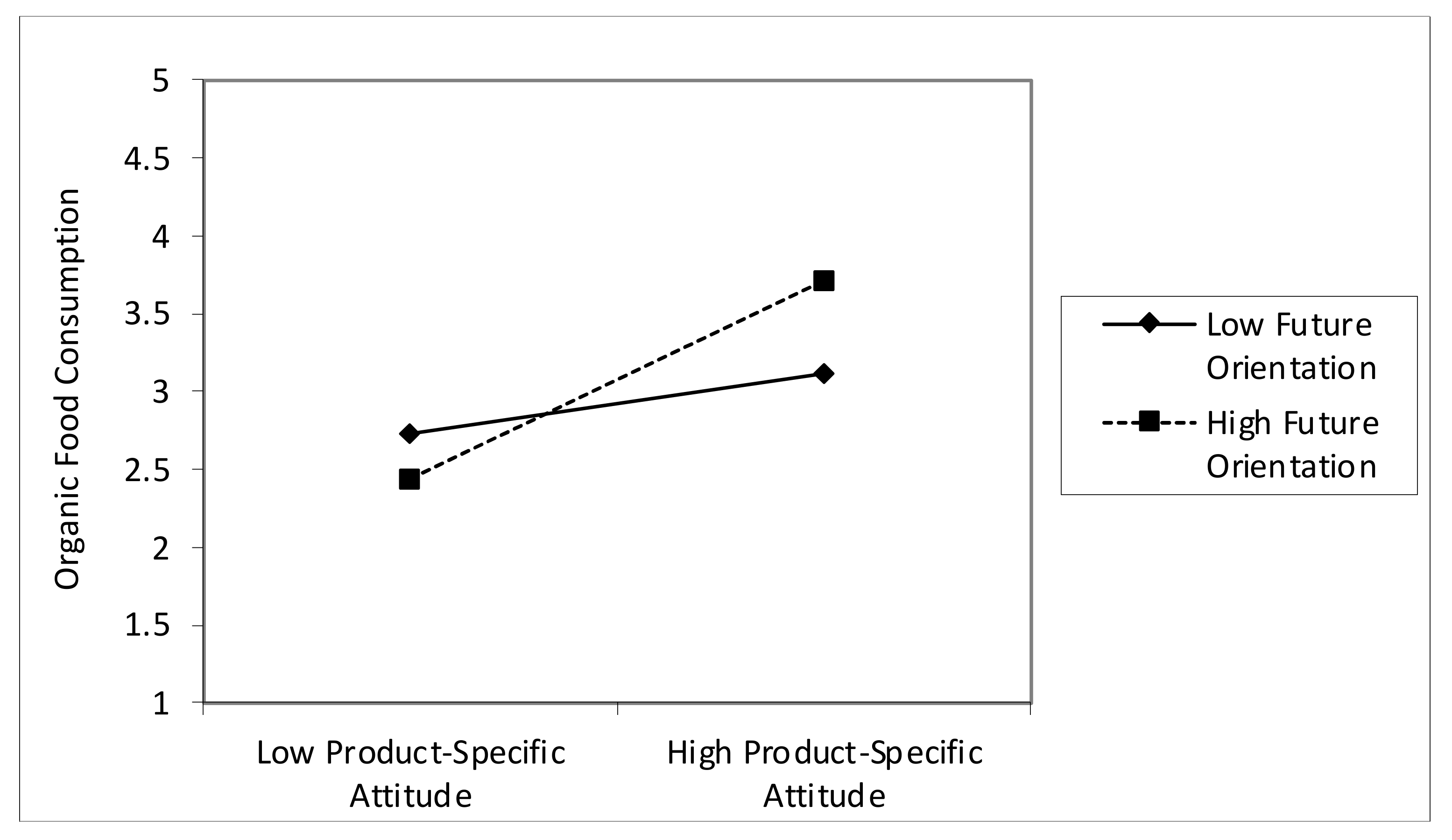

4.3. Assessment of the Structural Model

5. Discussion

6. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alcorta, A.; Porta, A.; Tárrega, A.; Alvarez, M.D.; Vaquero, M.P. Foods for plant-based diets: Challenges and Innovations. Food 2021, 10, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willer, H.; Lernoud, J. (Eds.) The World of Organic Agriculture. Statistics and Emerging Trends 2021; Research Institute of Organic Agriculture (FiBL), Frick and IFOAM–Organics International: Bonn, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- DOA. Reports on the Progress Production for Organic Certified Farm; Jabatan Pertanian Malaysia: Putrajaya, Malaysia, 2021.

- Statista Research Department. 5 October 2022. Malaysia: Frequency of Purchasing Organic Food 2021. Statista. Retrieved 28 March 2023. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1010541/frequency-buying-organic-food-malaysia/#:~:text=According%20to%20a%20survey%20on,never%20bought%20organic%20food%20products (accessed on 28 March 2023).

- Futerra, S.C.L. The Rules of the Game: The Principals of Climate Change Communication; Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs: London, UK, 2005.

- Malaysian Organic Certification Scheme (Myorganic). Official Portal of the Department of Agriculture. (n.d.). Available online: http://www.doa.gov.my/index.php/pages/view/377 (accessed on 28 March 2023).

- FiBL Statistics. Available online: https://statistics.fibl.org/europe.html (accessed on 1 April 2022).

- Belz, F.-M.; Ken, P. Sustainability Marketing; Wiley & Sons: Glasgow, Scotland; Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hansmann, R.; Baur, I.; Binder, C.R. Increasing organic food consumption: An integrating model of drivers and barriers. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 275, 123058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chekima, B. The Dilemma of Purchase Intention: A Conceptual Framework for Understanding Actual Consumption of Organic Food. Int. J. Sustain. Econ. Manag. (IJSEM) 2018, 7, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, A.K. Thinking green, buying green? Drivers of pro-environmental purchasing behavior. J. Consum. Mark. 2015, 32, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Jiang, B.; Zeng, H.; Kassoh, F.S. Impact of trust and knowledge in the food chain on motivation-behavior gap in green consumption. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 66, 102955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadiq, M.; Adil, M.; Paul, J. Organic food consumption and contextual factors: An attitude–behavior–context perspective. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2022. Ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenindex. 2012. Available online: https://globescan.wpenginepowered.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/Greendex_2012_Full_Report_NationalGeographic_GlobeScan.pdf (accessed on 22 December 2022).

- Gleim, M.; Lawson, S. Spanning the gap: An examination of the factors leading to the green gap. J. Consum. Mark. 2014, 31, 503–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moisander, J.; Markkula, A.; Eräranta, K. Construction of consumer choice in the market: Challenges for environmental policy. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2010, 34, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miniero, G.; Codini, A.; Bonera, M.; Corvi, E.; Bertoli, G. Being green: From attitude to actual consumption. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2014, 38, 521–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morwitz, V. Consumers’ Purchase Intentions and their Behavior. Found. Trends Mark. 2014, 7, 181–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabi Nabi, R.L. Anger, fear, uncertainty, and attitudes: A test of the cognitivefunctional model. Commun. Monogr. 2002, 69, 204–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimal, R.N.; Real, K. Understanding the Influence of Perceived Norms on Behaviors. Commun. Theory 2003, 13, 184–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. Consumer attitudes and behavior: The theory of planned behavior applied to food consumption decisions. Riv. Di Econ. Agrar. 2015, 70, 121–138. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M. Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behavior; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Thogersen, J.; Ruan, Y.; Huang, G. The moderating role of human values in planned behavior: The case of Chinese consumers’ intention to buy organic food. J. Consum. Mark. 2013, 30, 335–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aertsens, J.; Verbeke, W.; Mondelaers, K.; Van Huylenbroeck, G. Personal determinants of organic food consumption: A review. Br. Food J. 2009, 111, 1140–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gad Mohsen, M. Organic Food Adoption: A Temporally-Dynamic Value-Based Decision Process. In Proceedings of the 3rd Global Conference on Business Management (GCBM 2015), Singapore, 17–18 August 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Zimbardo, P.G.; Boyd, J.N. Putting temporal in perspective: A valid, reliable individual-differences metric. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 77, 1271–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behavior. In Action-Control: From Cognition to Behavior; Kuhl, J., Beckman, J., Eds.; Springer: Heidelberg, Germany, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I.; Sheikh, S. Action versus inaction: Anticipated affect in the theory of planned behavior. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2013, 43, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Barreiro, L.M.; Fernandez-Manzanal, R.; Serra, L.M.; Carrasquer, J.; Murillo, M.B.; Morales, M.J.; Calvo, J.M.; Valle, J.D. Approach to a causal model between attitudes and environmental behaviour. A graduate case study. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 48, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Ogden, D.T. To buy or not to buy? A social dilemma perspective on green buying. J. Consum. Mark. 2009, 26, 376–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeir, I.; Verbeke, W. Sustainable food consumption among young adults in Belgium: Theory of planned behaviour and the role of confidence and values. Ecol. Econ. 2008, 64, 542–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heberlein, T.A.; Black, J.S. Attitudinal specificity and the prediction of behavior in a field setting. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1976, 33, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, attitude, intention, and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. Philos. Rhetor. 1977, 10, 130–132. [Google Scholar]

- Marchand, A.; Walker, S. Product development and responsible consumption: Designing alternatives for sustainable lifestyles. J. Clean. Prod. 2008, 16, 1163–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard, M.; Habibi, M.R.; Laroche, M.; Paulin, M. Recent Advances in Online Consumer Behavior. In Encyclopedia of E-Commerce Development, Implementation, and Management; Lee, I., Ed.; Business Science Reference: Hershey, PA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Milfont, T.L.; Wilson, J.; Diniz, P. Time perspective and environmental engagement: A meta-analysis. Int. J. Psychol. 2012, 47, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thogersen, J.; Olander, F. Spillover of environment-friendly consumer behavior. J. Environ. Psychol. 2003, 23, 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oreg, S.; Katz-Gerro, T. Predicting Proenvironmental Behavior Cross-Nationally: Values, the Theory of Planned Behavior, and Value-Belief-Norm Theory. Environ. Behav. 2006, 38, 462–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Swidi, A.; Huque, S.M.; Hafeez, M.H.; Shariff, M.N. The role of subjective norms in theory of planned behavior in the context of organic food consumption. Br. Food J. 2014, 116, 1561–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peattie, K. Green Consumption: Behaviour and Norms. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2010, 35, 195–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarkiainen, A.; Sundqvist, S. Subjective norms, attitudes and intentions of Finnish consumers in buying organic food. Br. Food J. 2005, 107, 808–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, S.O.; Heide, M.; Dopico, D.C.; Toften, K. Explaining intention to consume a new fish product: A cross-generational and cross-cultural comparison. Food Qual. Prefer. 2008, 19, 618–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbeke, W.; Vackier, I. Profile and effects of consumer involvement in fresh meat. Meat Sci. 2004, 67, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saba, A.; Vassallo, M. Consumer attitudes toward the use of gene technology in tomato production. Food Qual. Prefer. 2002, 13, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chekima, B.; Chekima, K. The Impact of Human Values and Knowledge on Green Products Purchase Intention. In Exploring the Dynamics of Consumerism in Developing Nations; Gbadamosi, A., Ed.; IGI Global: Hersey, PA, USA, 2019; pp. 266–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavite, H.J.; Mankeb, P.; Suwanmaneepong, S. Community enterprise consumers’ intention to purchase Organic Rice in Thailand: The moderating role of Product Traceability Knowledge. Br. Food J. 2021, 124, 1124–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, H.C.; Chovancová, M.; Hoang, T.Q. The theory of planned behavior and Food Choice Questionnaire toward organic food of millennials in Vietnam. Glob. Bus. Financ. Rev. 2022, 27, 83–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, L.H. The dynamics of green consumption: A matter of visibility? J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2000, 2, 193–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, N.J.; Cialdini, R.B.; Griskevicius, J. A Room with a Viewpoint: Using Social Norms to Motivate Environmental Conservation in Hotels. J. Consum. Res. 2008, 35, 472–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolan, J.M.; Schultz, P.; Cialdini, R.B.; Goldstein, N.J.; Griskevicius, V. Normative social influence is underdetected. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2008, 34, 913–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gockeritz, S.; Schultz, P.; Rendon, T.; Cialdini, R.B.; Goldstein, N.J.; Griskevicius, V. Descriptive normative beliefs and conservation behavior: The moderating roles of personal involvement and injunctive normative beliefs. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 40, 514–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparks, P.; Shepherd, R. Self-identity and the theory of planned behavior: Assesing the role of identification with “green consumerism”. Soc. Psychol. Q. 1992, 55, 388–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Pelsmacker, P.; Janssens, W.; Sterckx, E.; Mielants, C. Consumer preferences for the marketing of ethically labelled coffee. Int. Mark. Rev. 2005, 22, 512–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liobikienė, G.; Mandravickaitė, J.; Bernatonienė, J. Theory of planned behavior approach to understand the green purchasing behavior in the EU: A cross-cultural study. Ecol. Econ. 2016, 125, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, J.; Rana, J. Consumer behavior and purchase intention for organic food. J. Consum. Mark. 2016, 29, 412–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeir, I.; Verbeke, W. Sustainable food consumption: Exploring the consumer “attitude–behavioral intention” gap. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2006, 19, 169–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boobalan, K.; Sivakumaran, B.; Susairaj, M. Organic food preferences: A comparison of American and Indian consumers. Food Qual. Prefer. 2022, 101, 104627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kluckhohn, F.R.; Strodtbeck, F.L. Variations in Value Orientations; Row, Peterson: Evanston, IL, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Mowen, J.C.; Mowen, M.M. Time and outcome valuation: Implications for marketing decision making. J. Mark. 1991, 55, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertoli, G.; Bonera, M.; Codini, A.; Corvi, E.; Miniero, G. Green behavior: How to encourage it. In Proceedings of the 42nd Annual European Marketing Academy Conference (EMAC), Istanbul, Turkey, 4–7 June 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Tangari, A.H.; Smith, R.J. How the temporal framing of energy savings influences consumer product evaluations and choice. Mark. Lett. 2012, 29, 198–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jager, W. Modelling Consumer Behavior; University of Groningen: Groningen, The Netherlands, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Carmi, N. Caring about tomorrow: Future orientation, environmental attitudes and behaviors. Environ. Educ. Res. 2013, 19, 430–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonidou, L.C.; Eteokleous, P.P.; Christofi, A.-M.; Korfiatis, N. Drivers, outcomes, and moderators of consumer intention to buy organic goods: Meta-analysis, implications, and future agenda. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 151, 339–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polonsky, M.J.; Vocino, A.; Grimmer, M.; Miles, M.P. The interrelationship between temporal and environmental orientation and pro-environmental consumer behaviour. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2014, 38, 612–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrington, M.; Neville, B.A.; Whitwell, G.J. Why ethical consumers dont’s walk their talk: Towards a framework for understanding the gap between the ethical purchase intentions and actual buying behaviour of ethically-minded consumers. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 97, 139–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chekima, B. Consumer Values and Green Products Consumption in Malaysia: A Structural Equation Modelling Approach. In Green Business: Concepts, Methodologies, Tools, and Applications; Management Association, I., Ed.; IGI Globa: Hershey, PA, United States, 2019; pp. 206–231. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson Jackson, T. Motivating Sustainable Consumption: A Review of Evidence on Consumer Behavior and Behavior Change. A Report to the Sustainable Development Research Network. Policy Studies Institute, London. 2005. Available online: http://hiveideas.com/attachments/044_motivatingscfinal_000.pdf (accessed on 23 January 2022).

- Steptoe, A.; Pollard, T.M.; Wardle, J. Development of a measure of the motives underlying the selection of food: The food choice questionnaire. Appetite 1995, 25, 267–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magnusson, M.K.; Arvola, A.; Hursti, U.K.; Åberg, L.; Sjödén, P.O. Attitudes towards organic foods among Swedish consumers. Br. Food J. 2001, 103, 209–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botonaki, A.; Polymeros, K.; Tsakiridou, E.; Mattas, K. The role of food quality certification on consumers’ food choices. Br. Food J. 2006, 108, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moussa, S.; Touzani, M. The perceived credibility of quality labels: A scale validation with refinement. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2008, 32, 526–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usunier, J.C.; Valette-Florence, P. The Time Styles Scale: A review of developments and replications over 15 years. Time Soc. 2007, 16, 333–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Buchner, A.; Lang, A.G. Statistical power analyses using G* Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav. Res. Methods 2009, 41, 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouteraa, M.; Raja Hisham, R.R.I.; Zainol, Z. Challenges affecting bank consumers’ intention to adopt green banking technology in the UAE: A UTAUT-based mixed-methods approach. J. Islam. Mark. 2022. Ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouteraa, M.; Raja Hisham, R.R.I.; Zainol, Z. Exploring Determinants Of Customers’ Intention To Adopt Green Banking: Qualitative Investigation. J. Sustain. Sci. Manag. 2021, 16, 187–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouteraa, M.; Chekima, B.; Lajuni, N.; Anwar, A. Understanding Consumers’ Barriers to Using FinTech Services in the United Arab Emirates: Mixed-Methods Research Approach. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaker, D.A.; Day, G.S. Marketing Research; John Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2011, 19, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C.M.; Wende, S.; Becker, J.M. SmartPLS 3. SmartPLS GmbH, Boenningstedt. J. Serv. Sci. Manag. 2015, 10, 32–49. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W. How to write up and report PLS analyses. In Handbook of Partial Least Squares; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, J.F. Moderation in Management Research: What, Why, When, and How. J. Bus. Psychol. 2014, 29, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essoussi, L.H.; Zahaf, M. Exploring the decision-making process of Canadian organic food consumers: Motivations and trust issues. Qual. Mark. Res. Int. J. 2009, 12, 443–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juliana, N.; Lada, S.; Chekima, B.; Abdul Adis, A.-A. Exploring Determinants Shaping Recycling Behavior Using an Extended Theory of Planned Behavior Model: An Empirical Study of Households in Sabah, Malaysia. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhaimee, S.; Ibrahim, I.Z.; Abd Wahab, M.A.M. Organic Agriculture in Malaysia. FFTC Agric. Policy Artic. 2016. Available online: https://ap.fftc.org.tw/article/1010 (accessed on 1 March 2023).

- House House, R.J.; Dorfman, P.; Javidan, M.; Hanges, P.J.; Sully De Luque, M. Strategic Leadership Across Cultures: GLOBE Study of CEO Leadership Behavior and Effectiveness in 24 Countries; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lada, S.; Chekima, B.; Ansar, R.; Abdul Jalil, M.I.; Fook, L.M.; Geetha, C.; Bouteraa, M.; Abdul Karim, M.R. Islamic Economy and Sustainability: A Bibliometric Analysis Using R. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographics | Frequency (N = 252) | Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 103 | 40.9 |

| Female | 149 | 59.1 | |

| Age | 20–29 | 66 | 26.2 |

| 30–39 | 95 | 37.7 | |

| 40–49 | 48 | 19.0 | |

| 50 and above | 43 | 17.1 | |

| Yearly Household Income | RM 50,000 and below | 27 | 10.7 |

| RM 50,001–100,000 | 77 | 30.5 | |

| RM 100,001–150,000 | 98 | 39.0 | |

| RM 150,001–200,000 | 34 | 13.5 | |

| RM 200,001 and above | 16 | 6.3 |

| Construct | Item | Loadings | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Product-Specific Attitude | PSATT1 | 0.909 | 0.927 | 0.717 |

| PSATT2 | 0.872 | |||

| PSATT3 | 0.859 | |||

| PSATT4 | 0.844 | |||

| PSATT5 | 0.739 | |||

| Subjective Norm | SN1 | 0.898 | 0.915 | 0.782 |

| SN2 | 0.894 | |||

| SN3 | 0.861 | |||

| Availability | ATT1 | 0.882 | 0.899 | 0.749 |

| ATT2 | 0.862 | |||

| ATT3 | 0.852 | |||

| Organic Label | OL1 | 0.867 | 0.882 | 0.652 |

| OL2 | 0.85 | |||

| OL3 | 0.739 | |||

| OL4 | 0.766 | |||

| Future Orientation | FO1 | 0.908 | 0.921 | 0.745 |

| FO2 | 0.828 | |||

| FO3 | 0.882 | |||

| FO4 | 0.832 | |||

| Consumption | OFC | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Availability | 0.863 | ||||

| 2. Future Orientation | 0.087 | 0.85 | |||

| 3. Organic Food Consumption | 0.710 | 0.071 | 1 | ||

| 4. Product-Specific Attitude | 0.658 | 0.115 | 0.866 | 0.847 | |

| 5. Subjective Norm | 0.055 | 0.172 | 0.092 | 0.075 | 0.849 |

| Hypothesis | Relationship | Std. Beta | Std. Error | t-Value | Decision | f2 | Q2 | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | PSATT → OFAC | 0.790 | 0.103 | 7.631 ** | Supported | 0.386 | 0.566 | 0.548 |

| H2 | SN → OFAC | 0.033 | 0.038 | 0.869 | Not Supported | 0.045 | ||

| H3 | ATT → OFAC | 0.419 | 0.104 | 4.042 ** | Supported | 0.278 | ||

| H4 | PSATT*FO → OFAC | 0.226 | 0.082 | 2.36 ** | Supported | 0.183 | 0.617 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chekima, B.; Bouteraa, M.; Ansar, R.; Lada, S.; Fook, L.M.; Tamma, E.; Abdul Adis, A.-A.; Chekima, K. Determinants of Organic Food Consumption in Narrowing the Green Gap. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8554. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15118554

Chekima B, Bouteraa M, Ansar R, Lada S, Fook LM, Tamma E, Abdul Adis A-A, Chekima K. Determinants of Organic Food Consumption in Narrowing the Green Gap. Sustainability. 2023; 15(11):8554. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15118554

Chicago/Turabian StyleChekima, Brahim, Mohamed Bouteraa, Rudy Ansar, Suddin Lada, Lim Ming Fook, Elhachemi Tamma, Azaze-Azizi Abdul Adis, and Khadidja Chekima. 2023. "Determinants of Organic Food Consumption in Narrowing the Green Gap" Sustainability 15, no. 11: 8554. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15118554

APA StyleChekima, B., Bouteraa, M., Ansar, R., Lada, S., Fook, L. M., Tamma, E., Abdul Adis, A.-A., & Chekima, K. (2023). Determinants of Organic Food Consumption in Narrowing the Green Gap. Sustainability, 15(11), 8554. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15118554